Abstract

There is a growing consensus that gambling is a public health issue and that preventing gambling related harms requires a broad response. Although many policy decisions regarding gambling are made at a national level in the UK, there are clear opportunities to take action at local and regional levels to prevent the negative impacts on individuals, families and local communities. This response goes beyond the statutory roles of licencing authorities to include amongst others the National Health Service (NHS), the third sector, mental health services, homelessness and housing services, financial inclusion support. As evidence continues to emerge to strengthen the link between gambling and a wide range of risk factors and negative consequences, there is also a strong correlation with health inequalities. Because the North of England experiences increasing health inequalities, it offers an opportunity as a specific case study to share learning on reducing gambling-related harms within a geographic area. This article describes an approach to gambling as a public health issue identifying it as needing a cross-cutting, systemwide multisectoral approach to be taken at local and regional levels. Challenges at national and local levels require policy makers to adopt a ‘health in all policy’ approach and use the best evidence in their future decisions to prevent harm. A whole systems approach which aims to reduce poverty and health inequalities needs to incorporate gambling harm within place-based planning and draws on the innovative opportunities that exist to engage local stakeholders, builds local leadership and takes a collaborative approach to tackling gambling-related harms. This whole systems approach includes the following: (1) understanding the prevalence of gambling related harms with insights into the consequences and how individuals, their family and friends and wider community are affected; (2) ensuring tackling gambling harms is a key public health commitment at all levels by including it in strategic plans, with meaningful outcome measures, and communicating this to partners; (3) understanding the assets and resources available in the public, private and voluntary sectors and identifying what actions are underway; (4) raising awareness and sharing data, developing a compelling narrative and involving people who have been harmed and are willing to share their experience; (5) ensuring all regulatory authorities help tackle gambling-related harms under a ‘whole council’ approach.

Keywords: Gambling related harms, Local authority, Inequality, Systemwide approach, Public health, Practice, Policy, Commercial determinants of health, Gambling

Highlights

-

•

This piece presents the case for why gambling is a particularly unique public health issue which requires a cross-cutting, systemwide multisectoral approach.

-

•

It explores opportunities for action at national and local level, using examples of work underway.

-

•

It concludes with a call to action using lesson learnt from managing harms from similar public health threats.

Introduction

Every few years a new threat to the public's health emerges. From Ebola, SARS and COVID-19, to obesity and alcohol related harm, they require a broad, systematic, partnership and whole system public health response. So why should gambling be regarded as such a threat to health and managed through a public health response? Some of us enjoy a flutter on the Grand National, and it is a leisure activity widely enjoyed by many. In fact, 56% of us (in England) spent money on at least one gambling activity in the past year and 46% in the last four weeks.1 , 2

Scale of the problem

Gambling is a highly lucrative business, which the gambling industry in the UK making a gross gambling yield of £14.5bn between October 2017 and September 2019.3 As a consequence, gambling is a global corporate industry with the ability to rapidly evolve its products and services. The move to gambling online means that traditional harm reduction strategies are less likely to be effective at a population level and require more creative approaches.

We currently have limited data and evidence on gambling-related harms, especially when compared with our knowledge of other public health threats. Yet this is beginning to change, with the recent classification of gambling as an addictive behaviour and increasing recognition of harms stimulating interest in this field.4 Some countries are already leading the way in terms of reframing gambling as a public health issue, with Canada and Australia, and more recently closer to home, Wales,5, 6, 7 standing out as notable examples.

Gambling-related harms are diverse, ranging from risks to housing and homelessness, domestic violence, debt, family breakdown, depression and suicide. Certain groups are more vulnerable to harmful gambling – including men, young people, certain ethnic minority groups, homeless people and people with mental health and substance misuse issues. What is less evident is the impact beyond the individual gambler. The Citizens Advice Bureau suggests that, on average, for every person harmed by gambling between six and ten additional people are affected, from family, friends and colleagues, to the local community and society.8 There is also evidence of a social gradient in gambling behaviours and harm with deprived areas and groups most adversely affected. This is particularly evident in the North of England.9, 10, 11

Gambling among young people is a particular concern. More were gambling than participating in other risk-taking behaviours in accordance with a Gambling Commission survey which found that 2% of 11–15-year-olds self-reported as high risk or problem gamblers.12 What sets gambling apart, especially for this group as a unique public health issue, is the rapidly changing impact of technology on behaviour. The internet and smart phones have increased access and availability to gambling, and the lines are blurring between on-line gaming and gambling.13

One thing that separates gambling from other public health issues is the complexity of the relationship with, reliance on and involvement of the gambling industry. While not the focus of this piece, it is recognised as a central issue for consideration in any work to tackle gambling-related harms and has been addressed in depth in several recent articles.14, 15, 16

Opportunities for action

As gambling increasingly becomes acknowledged as a public health issue, strategies to reduce harm, including both prevention and treatment, are being actively developed in the North of England. By facilitating early intervention, it is hoped to reduce demand for treatment services, particularly mental health and addiction services, as well the police and voluntary services.17 Because no single measure is likely to be effective on its own, a system-wide approach is required at both national and local levels.

National policy

In the UK, gambling is unique compared with the other public health challenges in that the Department of Digital, Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) is the lead department of government for all gambling-related policy, unlike alcohol or tobacco where the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) takes the lead. This provides an opportunity to embed a ‘health in all policy’ approach across government led by a non-health arm of the government. In early 2018, a cross-government roundtable including ministers form Department for Education, DHSC and DCMS indicated gambling harm was high on many departments' agendas, and cross departmental discussions have subsequently been instituted, bringing together interested providers and the third sector with policy makers. Policy decisions are also influenced by the political process, for example, the decision to reduce the betting limits on Fixed Odd Betting Terminals was a key issue for the All Party Parliamentary Group. Further policy changes are being debated including introducing a statutory levy to replace the current donation-based system funding research, education and treatment.18 The growing evidence of the impact of gambling on health has led to a greater awareness of the need to link consideration of gambling into policy development to reduce harms related to wider determinants such as poverty, homelessness, deprivation, and health inequalities. In addition, the structure of the NHS in the UK provides an opportunity for system-wide approaches to be developed but debate continues around the anomalous situation in which funding for the majority of research, education and treatment is currently supported through voluntary donations from the gambling industry and how the NHS and other statutory services can best integrate approaches.

Local policy

At a local level, councils have considerable opportunities to prevent and support people harmed by gambling across a wide range of local services from licencing premises, inspections, home referral and supporting the homeless, housing, financial inclusion services, children's services and adult social care. A useful briefing produced by the Local Government Association and Public Health England (PHE) has been published outlining how to take a ‘whole council approach’ to gambling-related harms.10 Many councils are concerned about gambling related harms, although the current finance environment places constraints on gambling being prioritised among existing issues. A clear challenge is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the scale of harm and how it is contributing to demand for local services. Yorkshire and Humber, Manchester and Westminster19 , 20 are good examples of local authorities which have prioritised gambling in recent years, with the Leeds model outlined separately in this issue. These local approaches highlight the need for collaboration not only across sectors with the local authority but also across other local services such as primary care and those in the third sector.

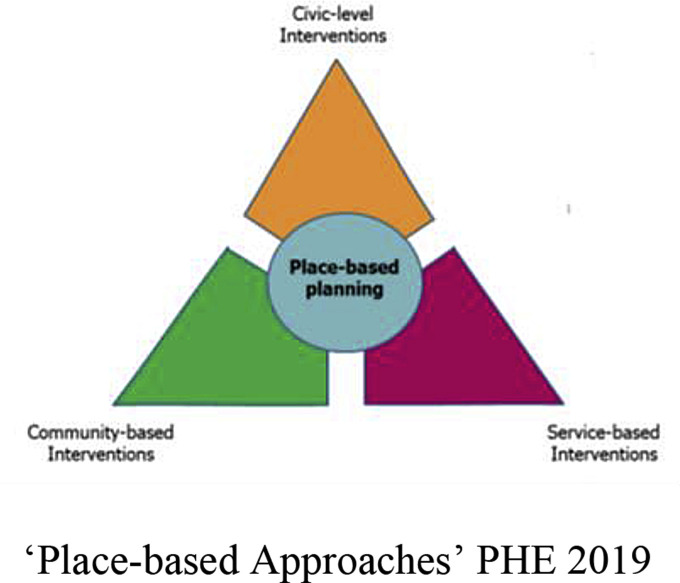

Given the multifaceted nature of the causes and consequences of harmful gambling an integrated and place-based approach is needed more than ever. This brings together the statutory and non-statutory sectors with communities themselves to identify the need and actions for prevention and treatment. To support place-based planning PHE has published a framework – ‘Place Based Approaches’.21 Key to this approach is the ‘population health triangle’ which stresses the need to bring together all civil level interventions led by the local authority with the NHS and communities using an asset approach-building.

Treatments

Until recently specific treatment for problem gambling was primarily provided by charities and one NHS clinic funded via voluntary donations from the gambling industry, as described elsewhere among these articles. Given that a proportion of problem gamblers are likely to seek treatment through existing mental health and substance misuse services there have been pledges for further investment in NHS provided services.22 The NHS Long Term Plan now pledges to increase support and treatment for problem gambling, by providing additional treatment centres across the country.22 But there will also be a need to increase awareness of gambling amongst professionals to enable them to identify and signpost to appropriate treatment and support. This will require education, training and support to be maximally effective.

Still to come …

Yet despite these early forays, more research and evidence are needed to support advocacy and action, as outlined in recent publications from the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling and Gambling Commission.23, 24, 25 There is a need for better understanding of the prevalence and impact of gambling harm, its determinants and the social and economic burden of gambling-related harms and how best to inform policy and practice. Two complementary evidence reviews, being undertaken by PHE and University of Sheffield (commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research) are to be published in 2020, which will address some of these knowledge gaps.26 , 27 In addition, amongst other initiatives, a House of Lords Select Committee review into the social and economic impact of the gambling industry is underway and will report in 2020.28 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence have committed to scoping the feasibility of developing treatment guidance for gambling.29

Call to action

The challenge for policy makers and practitioners is implementing the most effective and cost-effective set of policies at a national and local level. The evidence base to support policy makers and gaps for more research is getting stronger. It is also possible to use lessons learnt from managing harms from other public health threats, such as alcohol, tobacco, obesity, and drug use – acknowledging the unique characteristics of gambling, such as rapid technological advances and growth of gaming and on-line gambling.

Approaches need to move the focus from ‘personal responsibility’ to social, economic and environmental interventions at the population level. Lessons from other fields show that interventions which target individual behaviour can inadvertently increase inequalities in behaviour, thus it is essential to consider the broader context in all planning for tackling gambling-related harms.30

We suggest that a public health approach to reduce gambling-related harms needs to be multifaceted, combining upstream and downstream approaches applied in a coordinated way, and to include advocacy, information sharing, early intervention and regulation. This should include the following:

-

•

national and local policy makers adopting a ‘health in all policy’ approach and using the best evidence in their future decisions to prevent harm. This will ensure that gambling is seen within its widest context.

-

•

understanding the prevalence of harmful gambling with insights into the consequences and how individuals, their family and friends, and wider community are affected. To be effective at a local level in addressing gambling harms, it is not just the gambler but affected others who may suffer adverse impact.

-

•

ensuring tackling gambling harms is a key public health commitment at all levels by including it in strategic plans, with meaningful outcome measures, and communicating this to partners. This will require local agencies to consider gambling as they pull together their plans for action and to develop performance management systems to monitor progress.

-

•

understanding the assets and resources available in the public, private and voluntary sectors and identifying what actions are underway. By drawing together local assets a coordinated and collaborative local response can be effected.

-

•

raising awareness and sharing data, developing a compelling narrative and involving people who have been harmed and are willing to share their experience. Many people do not understand gambling as a health harm and developing the narrative, through campaigns will help to raise awareness.

-

•

ensuring all regulatory authorities help tackle gambling-related harms under a ‘whole council’ approach. Taking a cross-council approach will enable consideration of gambling within different contexts such as homelessness, vulnerability, poverty and local regulation.

-

•

developing a whole systems approach to reducing poverty and health inequalities that incorporates gambling harm within place-based planning. Understanding how gambling harm is impacting on health inequalities or is linked to inequalities amongst high-risk groups will help develop policies and target resources appropriately.

As we look to the future we hope that by raising the awareness of gambling harms and of steps that can be taken to reduce those harms, we will create healthier societies through effective evidence-based local action within a comprehensive national framework.

Author statements

Ethical approval

None sought.

Funding

None declared.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1.NHS Digital . Dec 2017. Health survey for England, 2016.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2016 (accessed 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambling Commission . Feb 2019. Gambling participation in 2018:behaviour, awareness and attitudes Annual report. (accessed 01 Oct) https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-participation-in-2018-behaviour-awareness-and-attitudes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambling Commission. Gambling Industry Statistics webpage (accessed 01 Oct 2019) https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/Statistics-and-research/Statistics/Industry-statistics.aspx.

- 4.World Health Organisation . 2018. ICD-11 (mortality and morbidity statistics.https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-m/en (accessed 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation . Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation; Australia: 2015. Using a public health approach in the prevention of gambling-related harm. Background paper. [Google Scholar]

- 6.GREO . Canada: GREO; 2017. Applying a public health perspective to gambling harm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chief Medical Officer for Wales . Welsh Government; Wales: 2019. Gambling with our health chief medical officer for Wales annual report 2016/2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nash E., MacAndrews N., Edwards S. Citizens Advice; UK: 2018. Out of luck an exploration of the causes and impacts of problem gambling. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrà G., Crocamo C., Bebbington P. Gambling, geographical variations and deprivation: findings from the adult psychiatric morbidity survey. Int Gambl Stud. 2017;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.LGA/PHE . Local Government Association; England: 2018. Tackling gambling related harm- a whole council appropach. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald L., Olsen J.R., Shortt N.K., Ellaway A. Do ‘envirornmental bads’ such as alcohol, fast food, tobacco, and gambling outlets cluster and co-locate in more deprived areas in Glawgow City, Scotland? Health Place. 2018;51:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambling Commission, Young People and Gambling . 2016. A research study among 11-15 year olds in England and Wales. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parliament. Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. Immersive and addictive technologies inquiry webpage. (accessed 01 Oct 2019) https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/digital-culture-media-and-sport-committee/inquiries/parliament-2017/immersive-technologies/.

- 14.Livingstone C., Adams P., Cassidy R., Markham F., Reith G., Rintoul A., Schüll N.D., Woolley r., Young M. On gambling research, social science and the consequences of commercial gambling. Int Gambl Stud. 2018;18(1):56–68. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2017.1377748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyder E., Blank L., Baxter S., Van Schalkwyk M. Tackling gambling related harms as a public health issue. Lancet Publ Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30243-9. 1 E14-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Schalkwyk M., Cassidy R., McKee M., Petticrew M. 2019. Gambling control: in support of a public health response to gambling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon N., Thomson K., Kaner E., Bambra C. Effects of prevention and harm reduction interventions on gambling behaviours and gambling related harm: an umbrella review. Addict Behav. 2019;90:p380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NHS England . June 2019. NHS to launch young people's gambling addiction service.https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/06/nhs-to-launch-young-peoples-gambling-addiction-service/ (accessed 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 19.City of Westminster. Gambling Research webpage (accessed 01 Oct) https://www.westminster.gov.uk/gambling-research.

- 20.Yorkshire and Humber Public Health Network Working Group . ADPH; England: Sept 2019. Public health framework for gambling related harm reduction. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health England . PHE; England: 2019. Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities: main report. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS . 2019. NHS Long term plan.https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 23.John Ann, Wardle H., McManus S., Dymond S. July 2019. Report 3 scoping current evidence and evidence-gaps in research on gambling- related suicide.https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/Report-3-Gambling-related-suicide-and-suicidal-behaviours.pdf (access 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wardle H., Reith G., Best D., McDaid D., Platt S. Gambling commission, ABSG, Gambleaware; UK: 2018. Measuring gambling-related harms A framework for action. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blake M., Pye J., Mollidor C., Morris L., Wardles H., Reith G. Ipsos MORI; England: April 2019. Measuring gambling-related harms among children and young people: a framework for action. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health England (2019) Gambling related harms: evidence review webpage. (accessed 01 Oct 2019) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review.

- 27.University of Sheffield. Public Health Review Team Ongoing Projects webpage. (accessed 01 Oct 2019) https://scharr.dept.shef.ac.uk/phrt/ongoing-topics/.

- 28.Parliment. House of Lords. Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry webpage. (accessed 01 Oct 2019) https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/406/gambling-industry-committee.

- 29.National Institute for health and care excellence . 2019. Gambling.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/proposed/gid-qs10099 (accessed 01 Oct) [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGill R., Anwar E., Orton L., Bromley H., Lloyd-Williams F., O'Flaherty M. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15:457. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1781-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]