Abstract

Imatinib mesylate is a small tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets BCR-ABL, ckit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor. It is prescribed by hematologists for chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia and by oncologists for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST). Cutaneous reactions to Imatinib are common but their incidence and severity widely varies between patients. A self-limited skin rash is the most common adverse effect but there have been reported cases of patients with maculopapular rash, pigmentary changes, superficial edema and rarer and clinically distinctive features such as lichenoid reactions or psoriasis. We here describe for the first time a case of pyoderma gangrenosum–like necrotizing panniculitis, a rare dermatological condition, after initiating therapy with Imatinib.

Key Words: Imatinib, pyoderma gangrenosum- like, necrotizing panniculitis

Case Report

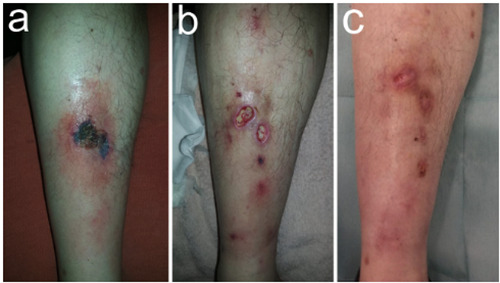

A 53-year-old man with stage IIIa gastrointestinal tumor of the stomach (pT3cN0cM0) positive for KIT (CD117) and high risk of relapse was started with Imatinib 400mg daily for 36 months in an adjuvant setting after laparoscopic removal of the tumor. The patient exhibited durable response and acceptable tolerance, however, after a year and two months he presented one black crusted plaque on the anterior surface of the right lower limb that caused redness and swelling of the surrounding skin (Figure 1a). No history of trauma was reported and no signs of systemic infection were present. Blood tests showed no abnormalities.

Under the clinical suspicion of tick bite or spider bite he was started on 1 monthcourse of doxycycline with ibuprofen, but failed to improve and after two weeks new lesions appeared in the form of ulcers with erythematous-violaceous raised edges and a fibrinous layer, all localized in the same extremity close to the first lesion (Figure 1b). After a risk-benefit analysis, Imatinib was discontinued under suspicion of a late onset adverse effect. Punch biopsy of the ulcer edge showed acute and non-specific chronic inflammation of the dermis (Figure 2a) with extensive necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2b) Full-body computed tomography found no evidence of disease progression while anti-cardiolipin antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anticentromere antibodies tests resulted negative. Laboratory and biopsy results led to the definitive diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum- like necrotizing panniculitis.

In addition to Imatinib withdrawal, the patient received 1mg of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and was started on prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d for 45 days and cyclosporine 4mg/kg/d and for 30 days. He rapidly improved and on 3 weeks the size of the injuries had reduced to 40% with no new lesions and no signs of infection, to finally resolve completely (Figure 1c). After 6 months, no relapse was observed and he still remains asymptomatic.

Discussion

It is often difficult to categorize a panniculitis given their heterogeneous nature. Regrettably, commonly used punch biopsies yield insufficient amounts of subcutaneous adipose tissue for a full histopathologic assessment. When possible, panniculitides are categorized by the pattern of the inflammatory cell infiltrate into lobular panniculitides, such as erythema induratum (also known as “nodular vasculitis”) or septal panniculitides like erythema nodosum,1 but histopathological findings depend on the stage of evolution and may vary among samples. In our case the biopsy showed perivascular inflammation with septal vascular alterations and lymphohistiocytic infiltration that had intensively extended into the lobule, but necrosis was so prevalent it was not possible to establish the predominance with certainty. Interestingly, erythema induratum is typically characterized for presenting ulcerating nodular lesions. Its predominant relation to tuberculosis is well-known, but it has also been associated with hepatitis C, inflammatory bowel disease or drugs.2

In our patient, Imatinib withdrawal and steroid-cyclosporine therapy led to an almost complete resolution of the lesions. Anti-phosphopholipid syndrome and Wegener’s granulomatosis were discarded after antibodies tests resulted negative, and a full body computed tomography discarded pancreatitis or disease progression. Patients with pancreatitis or α-1-antitrypsin deficiency have been reported to develop panniculitis with zones of fat necrosis as a complication, 3 in our case lab tests results did not show this deficiency. Based on our findings, a cause-effect relationship for Imatinib was deemed highly likely in the Naranjo and WHO-UMC probability scales for drug adverse reactions,4 and so it was reported to our local Pharmacovigilance Center.

Imatinib mesylate has often been reported for its cutaneous manifestations (rash,5 hypopigmentation,6 superficial edema, psoriasis, 7 and lichenoid reactions8) but it has seldom been associated with panniculitis with necrotic ulceration. Ugurel et al,9 and Breccia et al,10 both described a case of panniculitis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia using Imatinib. Also, Imatinib has several times been linked to neutrophilic dermatoses, such as acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Sweet syndrome and neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis,11–13 but the mechanism behind these adverse effects has yet to be fully understood. A case of pyoderma gangrenosum, a rare ulcerative neutrophilic dermatosis has also been documented in a patient treated with Imatinib.14 Myeloproliferation has been documented in mice at 10-fold lower doses than the usual, mimicking a physiological increment in number of circulating monocytes and neutrophils to a bone marrow infection.15 It has also been associated to endothelial apoptosis and increased endothelial permeability.16 Both phenomena could explain the induced subcutaneous ischemia, necrosis, and subsequent neutrophil infiltration seen in our patient. Interestingly, there have also been reports of drug-induced panniculitis with other c-Kit inhibitors such as ponatinib and nilotinib, 17,18 and pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcerations with sunitinib and pazopanib,19,20 hinting at a common mechanism.

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation and skin lessions evolution. a) A solitary initial lesion appeared pre-tibially on the right limb as a large and painful exulceration covered by a necrotic scar. b) Several painful ulcers with a fibrinous bed and an elevated, violaceous, undermined border, were observed two weeks after. c) Almost complete healing was observed three weeks after Imatinib was withdrawal.

Figure 2.

Hematoxiline-eosin stain of a 5 mm-punch biopsy taken on the advancing edge/raised border of established lesion. a) A combination of acute and non-specific chronic perivascular inflammation of the dermis shown at 40x. b) Lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, with occasional formation of multinucleated giant cells, extended into the septa and the lobule, along with extensive lipophagic necrosis, shown at 100x.

Conclusions

Clinicians should be aware of potential necrotizing panniculitis pyoderma gangrenosum- like in patients treated with Imatinib and consider stopping treatment until resolution of symptoms. Further studies ought to be performed to determine the exact mechanism linking Imatinib and other c-Kit inhibitor with their cutaneous side effects.

References

- 1.Segura S, Requena L. Anatomy and Histology of Normal Subcutaneous Fat, Necrosis of Adipocy tes, and Classification of the Panniculitides. Dermatol Clin 2008;26:419-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilchrist H, Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): Diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther 2010;23: 320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon MJ. Metabolic panniculitis: Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis and pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Ther 2010;23:368-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaki S. Adverse drug reaction and causality assessment scales. Lung India 2011;28:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basso FG, Boer CC, Corrêa MEP, Torrezan M, Cintra ML, De Magalhães MHCG, et al. Skin and oral lesions associated to Imatinib mesylate therapy. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsao AS, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, O’Brien S, Talpaz M. Imatinib Mesylate Causes Hypopigmentation in the Skin. Cancer 2003;98:2483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valeyrie L, Bastuji-Garin S, Revuz J, Bachot N, Wechsler J, Berthaud P, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to Imatinib (STI571) in Philadelphia chromosomepositive leukemias: A prospective study of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ena P, Chiarolini F, Siddi GM, Cossu A. Oral lichenoid eruption secondary to Imatinib (Glivec®). J Dermatolog Treat 2004;15:253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ugurel S, Lahaye T, Hildenbrand R, Glorer E, Reiter A, Hochhaus A, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukaemia treated with Imatinib. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breccia M, Carmosino I, Russo E, Morano SG, Latagliata R, Alimena G. Early and tardive skin adverse events in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients treated with Imatinib. Eur J Haematol 2005;74:121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu D, Seiter K, Mathews T, Madahar CJ, Ahmed T. Sweet’s syndrome with CML cell infiltration of the skin in a patient with chronic-phase CML while taking Imatinib Mesylate. Leuk Res 2004;28:61-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dib EG, Ifthikharuddin JJ, Scott GA, Partilo SR. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis induced by Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) therapy. Leuk Res 2005; 29:233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brouard MC, Prins C, Mach-Pascual S, Saurat J-H. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Associated with STI571 in a Patient with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Dermatol 2001; 203:57-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma R, Pinato D. Imatinib induced pyoderma gangrenosum. J Postgrad Med 2013;59:244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Napier RJ, Norris BA, Swimm A, Giver CR, Harris WAC, Laval J, et al. Low Doses of Imatinib Induce Myelopoiesis and Enhance Host Anti-microbial Immunity. PLoS Pathog 2015;11:1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vrekoussis T, Stathopoulos EN, De Giorgi U, Kafousi M, Pavlaki K, Kalogeraki A, et al. Modulation of Vascular Endothelium by Imatinib: A Study on the EA.hy 926 Endothelial Cell Line. J Chemother 2014;18:56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, Hassan KM, Musiek A, Rosman IS. Ponatinib-induced neutrophilic panniculitis. J Cutan Pathol 2014;41:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitayama N, Otsuka A, Hamamoto C, Kaku Y, Shiragami H, Okumura Y, et al. Nilotinib-induced panniculitis in a patient with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:e418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez Pineiro M, Willis E, Yao C, Chon SY. Pyoderma gangrenosum–like ulceration of the lower extremity secondary to sunitinib therapy: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2018;6: 2050313X18783048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usui S, Otsuka A, Kaku Y, Dainichi T, Kabashima K. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the penis possibly associated with pazopanib treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:1222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]