Abstract

This cross-sectional study reports parking fees at National Cancer Institute–designated cancer treatment centers to assess parking costs for the treatment duration of certain cancers.

The economic and personal distress resulting from the costs of cancer treatment has been referred to as financial toxicity. Nonmedical costs such as travel expenses are almost never reimbursed by insurance and can be a substantial out-of-pocket expense. This cross-sectional study aims to report parking fees at National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated cancer treatment centers and to assess parking costs for the treatment duration of certain cancers.

Methods

Parking fees from the 63 NCI-designated cancer treatment centers were obtained via online search or telephone call from September 1, 2019, to December 30, 2019. City cost of living score (with New York City as the base city with a cost of living expressed as 100; costs for other cities were indexed against this number), median city household income (calculated in 2018 dollars), center address transit score (with 0-24 indicating minimal transit options and 90-100 indicating world-class public transportation), and discount availability were documented. A zero-inflated negative binomial model was used to assess associations between parking costs and city variables. Pearson correlation was used for binary variables (RStudio version 1.2.5033; RStudio PBC). Parking costs were estimated for treatment of node-positive breast cancer (12 daily rates plus twenty 1-hour rates), definitive head and neck cancer (thirty-five 1-hour rates), and acute myeloid leukemia (42 daily rates). Data were analyzed in March 2020.

This study was determined to be exempt from approval with a waiver of patient informed consent as nonhuman participant research according to the general policies of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board. All P values were from 2-sided tests, and the results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

In this cohort study, parking costs were obtained for 100% of the 63 NCI treatment centers queried. Median city cost of living score was 75.0 (interquartile range, 70.1-83.5); median city household income was $55 295 (interquartile range, $46 696-$60 879); and median transit score was 61.0 (interquartile range, 50.8-72.5).

Twenty-five (40%) NCI-designated cancer treatment centers did not have detailed parking cost information online. Median parking costs were $2 per hour (interquartile range, $0-$5) and $5 per day (interquartile range, $0-$10). Twenty centers (32%) offered completely free parking for all patients. Free parking was available at 43 (68%) centers for radiation appointments and 34 (54%) centers for chemotherapy appointments. The median estimated parking cost including discounts for a course of treatment for breast cancer was $0 (range, $0-$800); for head and neck cancer, $0 (range, $0-$665); and for hospitalization for acute myeloid leukemia, $210 (range, $0-$1680) (Table).

Table. Parking Costs and Variables.

| Variable | Mean | Median (IQR) | Range, low-high | Locations with high and low range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median annual household city income, $a | 56 664 | 55 295 (46 696-60 879) | 28 974-124 573 | Cleveland, Ohio (low); La Jolla, California (high) |

| Cancer treatment center address transit scoreb | 64.0 | 61.0 (50.8-72.5) | 27.0-100.0 | Stanford Cancer Institute, Stanford, California (low); Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center at Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health; Tisch Cancer Institute at Mt Sinai; Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; New York, New York; Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (high) |

| City cost of living scorec | 77.3 | 75.0 (70.1-83.5) | 60.9-100.0 | San Antonio, Texas (low); New York, New York (high) |

| Cost of parking, $ | ||||

| Hour | 3.55 | 2 (0-5) | 0-19 | 23 centers had free parking for at least the first hour (low); Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University, New York, New York (high) |

| Day | 7.79 | 5 (0-10) | 0-40 | 20 centers had free parking for the entire day (low); Tisch Cancer Institute at Mt Sinai, New York, New York (high) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Calculated in 2018 dollars.

The transit score range is from 0 to 100, with 0 to 24 indicating minimal transit options and 90 to 100 indicating world-class public transportation.

New York City is normalized as the base city with a cost of living expressed as 100. Costs for other cities are indexed against this number. Twelve centers were not able to have cost of living scores calculated.

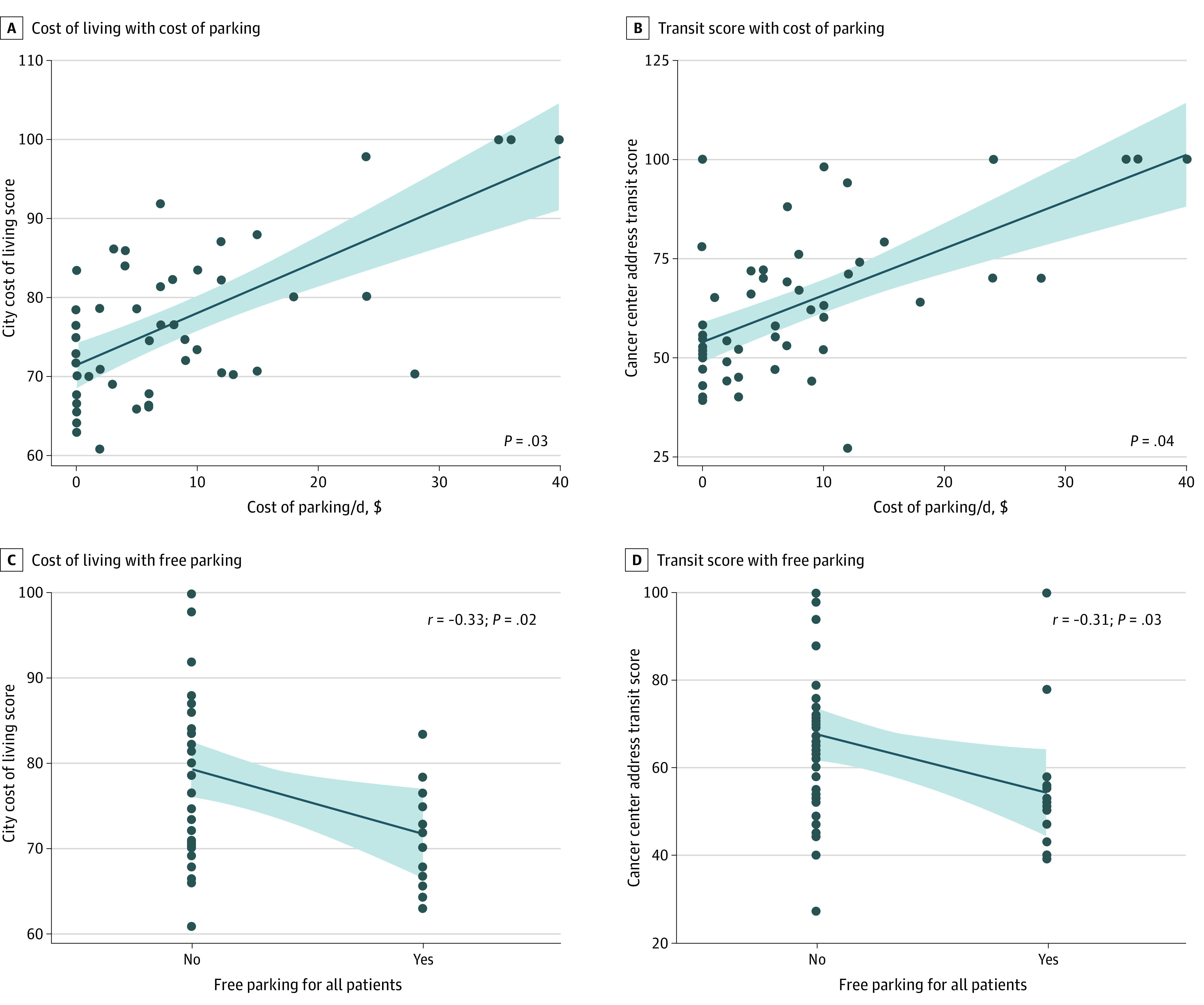

Daily parking costs were positively associated with city cost of living (coefficient: −0.10; standard error, 0.04; P = .03) and transit scores (coefficient: −0.04; standard error, 0.22; P = .04), while hourly parking costs were not. City cost of living was negatively correlated with both free daily parking (r = −0.33; P = .02) and free parking during radiation treatment (r = −0.46; P < .001) or chemotherapy (r = −0.40; P = .003). Transit score was negatively correlated with both free daily parking (r = −0.31; P = .03) and free parking during radiation treatment (r = −0.33; P = .02) or chemotherapy (r = −0.34; P = .01) (Figure). Median city household income was not correlated with any assessed variables.

Figure. Correlations Between City Variables and Parking Costs.

Each plotted dot represents a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer treatment center. The shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

Patients may face substantial nonmedical costs through parking fees, even at centers with the highest standard of care. We observed up to a 4-figure variability in estimated parking costs throughout the duration of a cancer treatment course. Additionally, 40% of centers did not list prices online so that patients could plan for costs. As treatment may span months and unexpected costs have been reported to be associated with decreased willingness to pay,1 high parking costs may be a source of financial toxicity to patients and caregivers and ultimately interfere with cancer care.

Previous research has found that transportation was the single highest out-of-pocket nonmedical cost for patients with cancer receiving treatment.2 The negative economic and psychological consequences of parking fees have been consistently noted in qualitative studies of patients with cancer and families.3,4 Because travel costs including parking may become a barrier to patients receiving optimal care,5 a 2017 study has specifically suggested subsidized parking as a way to ameliorate economic burden.6

Study limitations include the potential inaccuracy of costs collected via telephone, as the center staff contacted may not have had the full information or costs may have since changed. Estimated costs were conservative and did not incorporate extra trips for consultation, imaging procedures, or laboratory tests.

This study found high variability in costs with the potential for patients to pay hundreds of dollars in parking to receive cancer care. Efforts to minimize financial toxicity may benefit from a focus on this potentially underreported patient concern.

References

- 1.Chino F, Peppercorn JM, Rushing C, et al. Out-of-pocket costs, financial distress, and underinsurance in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(11):1582-1584. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houts PS, Lipton A, Harvey HA, et al. Nonmedical costs to patients and their families associated with outpatient chemotherapy. Cancer. 1984;53(11):2388-2392. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams HR, Leeds HS, Russell HV, Hellsten MB. Factors influencing family burden in pediatric hematology/oncology encounters. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;6(4):243-251. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridge E, Conn LG, Dhanju S, Singh S, Moody L. The patient experience of ambulatory cancer treatment: a descriptive study. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):e482-e493. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resio BJ, Chiu AS, Hoag JR, et al. Motivators, barriers, and facilitators to traveling to the safest hospitals in the United States for complex cancer surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184595. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balfe M, Keohane K, O’ Brien K, et al. In a bad place: carers of patients with head and neck cancer experiences of travelling for cancer treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;30:29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]