Abstract

Risk factors associated with the development of anxiety disorders have been identified; however, the development of preventive interventions targeting these risk factors is in the nascent stage. To date, preventive interventions have tended to target specific anxiety disorder symptoms (e.g., panic attacks). Although these interventions are effective at reducing risk for the targeted disorder (e.g., panic disorder), the focus of the intervention is narrow, thereby limiting the dissemination of these interventions. One approach that may broaden the scope of our prevention efforts is the development of a transdiagnostic intervention. Currently, transdiagnostic interventions have only been used in those with diagnosed conditions (e.g., anxiety disorders); however, it stands to reason that a transdiagnostic approach may also be helpful for those at-risk for developing anxiety disorders. The present study reported on the development and use of a brief preventative intervention for those with subclinical anxiety (i.e., worry, social anxiety). Participants were randomized into either a transdiagnostic preventative intervention, focused on reduction of safety aids, or a health focused control group. Participants consisted of sixty-nine individuals with subclinical levels of anxiety. Results revealed significant between group differences in the reduction of social anxiety, worry, and levels of impairment with the active intervention group relative to the control group. Further, change in safety aid utilization was a significant mediator in the association between intervention group and social anxiety and worry at Week 1; however, it was not a significant mediator at Month 1. Implications of these results and avenues for future research are discussed.

Keywords: transdiagnostic, prevention, intervention, subclinical, subthreshold, anxiety

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent forms of psychopathology (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). These disorders result in considerable distress, impairment in daily functioning and an economic burden of billions of dollars in any given year (Greenberg et al., 1999). Over the last several decades, empirically supported treatments have been developed to treat these conditions (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one form of treatment that has been shown to be an efficacious treatment for the anxiety disorders (Hofmann, Sawyer, Korte & Smits, 2009; Hofmann & Smits, 2008). Despite the effectiveness of these treatments, some individuals fail to respond to treatment (Wade et al., 1998), or have a reemergence of symptoms later in life (Yonkers, Bruce, Dyck, & Keller, 2003). Furthermore, the prevalence of anxiety disorders remains high, suggesting a need for increased efforts aimed at the prevention of these disorders.

Whereas considerable research has identified risk factors associated with the prospective development of anxiety disorders (e.g., neuroticism, Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; anxiety sensitivity, Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986; behavioral inhibition, Rosenbaum et al., 1993), the prevention of these disorders is in the nascent stage. There are several approaches that have been used in the area of prevention. Preventive interventions typically fall into one of three categories (1) universal (i.e. provide intervention to everyone regardless of risk), (2) selected (i.e., provide interventions to those at-risk for a disorder, and (3) indicated (i.e., provide intervention to those experiencing subclinical symptoms of a disorder (Gordon, 1983). To date, anxiety disorder preventative efforts have focused on selective and indicated interventions (Feldner, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2004).

Several selective interventions have been developed for use with individuals with elevated risk for anxiety disorders. The focus of these interventions is to alter malleable risk factors, such as anxiety sensitivity (Reiss & McNally, 1985). The existing interventions focus on providing individuals with anxiety psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral techniques (Feldner, Babson, Leen-feldner, & Schmidt, 2008; Keough & Schmidt, 2012; Schmidt et al., 2007) and exercise-based interventions (Smits et al., 2008) to ameliorate their elevated risk status. These interventions have been shown to be effective at reducing levels of anxiety sensitivity at post-intervention and at follow-up (Feldner et al., 2008; Keough & Schmidt, 2012; Smits et al., 2008). Moreover, there is also evidence that these interventions are associated lower rates of anxiety disorder diagnoses at a two-year follow-up (Schmidt et al., 2007).

A second approach to the prevention of anxiety disorders is through the use of indicated preventative interventions. Indicated preventative interventions aim to reduce risk of developing an anxiety disorder in those who are experiencing subclinical levels of anxiety. Similar to the selective interventions targeting anxiety sensitivity, indicated interventions also utilize a CBT based approach in developing the intervention techniques. As such, existing indicated preventative interventions have utilized anxiety-focused psychoeducation in youth with anxiety symptoms (Dadds et al., 1997; Dadds et al., 1999) and cognitive-behaviorally based interventions to reduce subclinical symptoms of specific anxiety disorders such as panic attacks (Gardenwartz & Craske, 2001) and subclinical social anxiety (Aune & Stiles, 2009). These initial investigations have been promising, showing reductions in the anxiety symptoms targeted by the intervention. However, selective preventative interventions are limited in that they largely focus on reducing elevated symptoms of a single disorder as opposed to targeting a broad range of anxiety symptoms that indicate risk for a variety of anxiety disorders. With this in mind, it seems that developing a preventative intervention to address a broad range of symptom dimensions may be the next step in developing preventative interventions for anxiety disorders. Indeed, this approach may increase the efficiency of preventative interventions by making them applicable to all anxiety disorders as opposed to having different preventative interventions for each anxiety disorder.

When developing a new preventative intervention, it is important to build on the prior work in the area. Based on prior research, we know that interventions centered on the use of cognitive-behavioral principles are efficacious preventative interventions for anxiety (Dadds et al., 1997; Dadds et al., 1999; Feldner et al., 2008; Gardenwartz & Craske, 2001; Keough & Schmidt, 2012; Smits et al., 2008). A potential limitation of the existing indicated preventative interventions, however, is the difficulty to disseminate these disorder specific interventions in the community. As Rapee (2008) discussed, one important component of a successful preventative intervention is its ability to target a large group of at-risk individuals (Rapee, 2008). Based on this consideration, it seems that developing a preventative intervention based on what we know about enhancing the efficiency and parsimony of our treatments for anxiety disorder patients may be an important next step when contemplating how to enhance the utility of preventative interventions. Of note, the literature on the development of transdiagnostic treatments may be particularly helpful to consider (Barlow et al., 2012; Norton, 2008; Riccardi, Korte, & Schmidt, 2017; Schmidt et al., 2012). Specifically, adapting the recently developed transdiagnostic treatments to use as a preventative intervention for a range of subclinical anxiety symptoms (e.g., panic, worry, social anxiety) may be helpful in broadening the impact of our preventive interventions.

Transdiagnostic treatments aim to provide a parsimonious approach to treatment by creating protocols designed to treat multiple disorders. These approaches have been developed to treat disorders that are deemed to be similar in nature and viewed to have the same underlying or maintaining factors and tend to be responsive to the same treatment mechanisms. Transdiagnostic approaches provide an attractive alternative to the complex disorder specific CBT protocols and have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of anxiety disorders (Barlow et al., 2011; Norton, 2008; Schmidt et al., 2012). To date, these protocols have only been used in those with diagnosed anxiety disorders; however, it stands to reason that a transdiagnostic approach may also be helpful for those at-risk for developing anxiety disorders. This is especially true for the risk group experiencing subclinical anxiety symptoms, as this group is likely to display a variety of anxiety symptoms such as subclinical panic attacks, social anxiety, worry, or fears of contamination. Indeed, the development of a transdiagnostic intervention for this group may be a key next step in providing a cost-effective preventative approach of these disorders.

Schmidt and colleagues (Riccardi, Korte, & Schmidt, 2017; Schmidt et al., 2012) have developed a transdiagnostic treatment approach for the anxiety disorders called, False Safety Behavior Elimination Treatment (F-SET) that may be effective as a preventative intervention for those with subclinical anxiety. F-SET was designed to treat multiple anxiety disorders through the identification and elimination of avoidance and coping strategies utilized by anxiety patients. These strategies, called safety aids, are ubiquitous across anxiety conditions and play a central role in the maintenance of anxiety conditions. A major strength of F-SET is the straightforward nature of the intervention, which focuses on the identification and elimination of safety aids that tend to be similar across anxiety disorders. The F-SET protocol is especially helpful in clients with multiple anxiety conditions who tend to use the same safety aids with each diagnosed anxiety condition. Many CBT protocols for anxiety include education, cognitive reappraisal, and exposure exercises. In F-SET, patients receive general psychoeducation, though training in cognitive therapy and exposure are not specifically covered. Nonetheless, the focus on eliminating safety aids and developing an anti-phobic approach commonly leads patents to complete exposure exercise during the course of treatment (Schmidt et al., 2012).

FSET may also be effective in those experiencing subclinical symptoms of anxiety. Those with subclinical anxiety are likely to be utilizing a number of safety aids to deal with their emerging level of anxiety. In fact, it has been suggested that the use of safety aids may actually play a role in the development of anxiety disorders in those experiencing subclinical levels of anxiety (i.e., elevated fears of contamination; Deacon & Maack, 2008). In addition, the use of safety aids has also been associated with higher levels of anxiety in individuals with elevated social anxiety (McManus, Sacadura, & Clark, 2008).

It stands to reason that the use of safety aids may play a key role in accelerating the development of an anxiety disorder. Once an individual starts using safety aids, they begin to attribute “safety” (i.e., reduction in anxiety) to their safety aids and view them as effective coping strategies. As the developmental trajectory progresses, the individual develops increasingly elevated levels of anxiety and the individual increases their safety aid use to cope with the elevation in their anxiety, resulting in a cyclic pattern. Although speculative, as this cyclic pattern progresses, the ratio of anxiety symptoms to coping strategies may eventually become imbalanced and the elevation in anxiety symptoms override the attempts to cope with anxiety, thereby leading to the development of a diagnosable anxiety disorder. With this in mind, it seems that providing subclinical individuals with an intervention focusing on eliminating the use of safety aids could correct these anxiety-maintaining behaviors early in the developmental trajectory, before they reach the level observed in those with anxiety disorder diagnoses.

The primary goal of the present study was to adapt the F-SET protocol to use as a preventative intervention for those with subclinical anxiety. The present study is a novel approach building on current prevention work by incorporating what we know about the use of preventative interventions, CBT, and transdiagnostic treatment approaches. This innovative design provides a preventive intervention that can be utilized across a range of anxiety symptom groups (e.g., panic attacks, worry, social anxiety), as opposed to focusing on one symptom cluster (e.g., panic attacks). The present study adapted the F-SET protocol to a shortened, easy-to-use, preventive intervention. To date, no studies have examined the efficacy of adapting a transdiagnostic treatment as an intervention for those with subclinical anxiety. For this reason, we are interested in examining this novel intervention in the present study.

To examine the efficacy of the transdiagnostic preventative intervention, we conducted a randomized controlled (RCT) trial examining the efficacy of the intervention in those with subclinical anxiety symptoms. Two non-treatment seeking subclinical anxiety symptom groups were collected, a social anxiety group and a generalized anxiety group, to provide an initial test of the efficacy of the intervention. The RCT allowed us to examine two primary hypotheses. First, we examined the effect of the intervention condition (i.e., transdiagnostic intervention or health education control) on the change in subclinical anxiety symptoms at the Week 1 check-in and the Month 1 follow-up as assessed by the clinician administered and self-report symptom measures. It was hypothesized that those in the transdiagnostic intervention condition would show lower levels of anxiety and impairment at the one-week check-in than those in the health education control condition. It was also hypothesized that this effect would be maintained at the one-month follow-up. Second, we examined the potential mechanisms of change (i.e., safety behavior utilization) associated with the change in anxiety symptoms. It was hypothesized that the changes in safety behavior utilization would mediate the association between experimental condition and anxiety symptoms at the one-week check-in and the one-month follow-up.

Methods

Participants

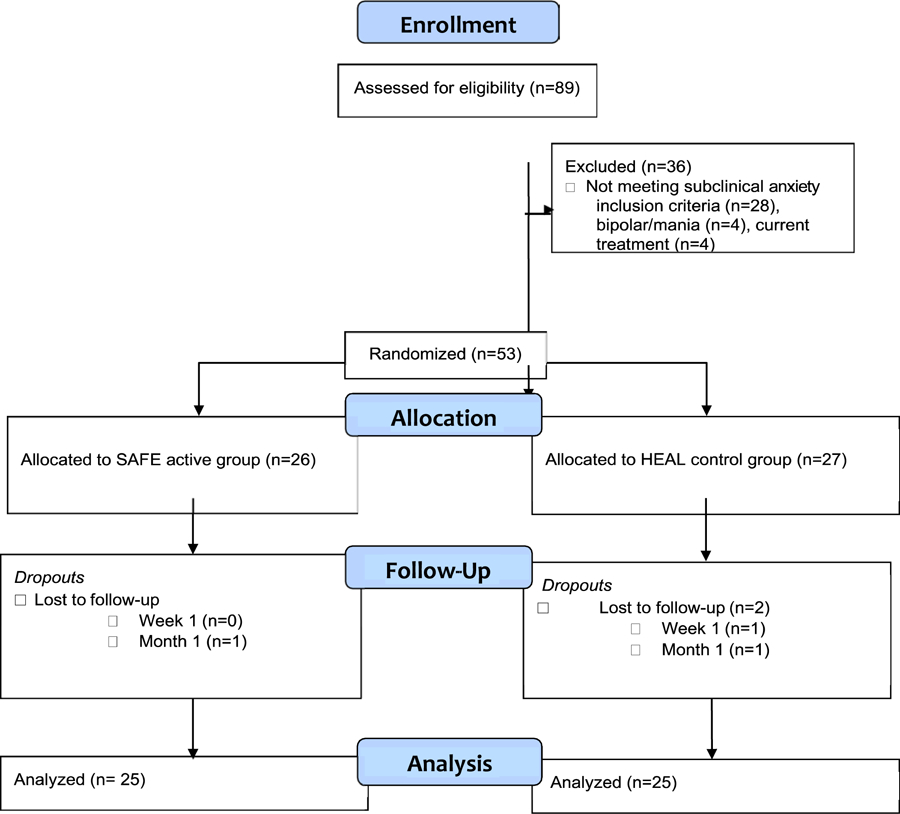

All procedures were approved by the local institutional review board and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. A total of 89 individuals were recruited to participate in the present study. Of the 89 participants, 36 did not meet eligibility criteria due to the following reasons: current anxiety disorder diagnosis (16 participants), suspected Bipolar Disorder (3 participants) or endorsement of a manic episode (1 participant), currently receiving weekly individual therapy (4 participants), or not meeting the threshold for subclinical social anxiety or worry (12 participants). Fifty-three participants were randomized to either the False Safety Behavior Elimination Intervention for Subclinical Anxiety (SAFE) active group (n = 26) or the Health Education and Adaptive Living (HEAL) control group (n = 27). A majority of the participants were White (74.4%) females with a mean age of 20.22 (SD = 2.81).

Participants were recruited from two sources: (1) undergraduate students from the psychology department’s undergraduate research pool and (2) community participants presenting for treatment at the Anxiety and Behavioral Health Clinic (ABHC). Participants were comprised of individuals reporting subclinical levels of social anxiety and generalized anxiety. Subclinical social anxiety was defined as scores between 20 and 36 on the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick and Clarke, 1998). Subclinical generalized anxiety was defined as scores between 40 and 65 on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990). These cutoffs for the SIAS and PSWQ are based on factor-mixture modeling (FMM; Lubke & Muthen, 2005) and subsequent ROC analyses conducted in our laboratory which established the presence of distinct subclinical social anxiety and generalized anxiety groups and the corresponding upper and lower bound cut-offs (Korte, Allan, & Schmidt, 2017). It is also notable that the upper bound cut-off is comparable to the clinical cut-offs established for each scale (Brown et al, 1997; Fresco et al, 2003) and that the lower bound cut-off is above the norm established for these scales (Rodebaugh et al., 2011; Gillis, Haaga, & Ford, 1995).

We recruited approximately equal numbers of individuals with subclinical social anxiety and subclinical generalized anxiety. We selected a sample with subclinical social anxiety and subclinical generalized anxiety because these groups represent segments of the population that have an elevated risk for developing anxiety psychopathology (Deacon & Maack, 2008; McManus, Sacadura, & Clark, 2008). In addition, we selected these two prevalent subclinical groups (social anxiety and generalized anxiety) because they tend to be easier to recruit than other subclinical anxiety symptoms (i.e., panic, OCD), thereby ensuring that we are able to recruit the desired number of participants while maintaining adequate power to test the primary aims of the study. Participants classified into the subclinical social anxiety and subclinical worry groups were evenly distributed throughout the SAFE and HEAL conditions. Of the total sample 26 individuals were classified as having subclinical levels of social anxiety (n = 26) and 27 had subclinical levels of worry. Approximately half of the participants meet the criteria for both subclinical social anxiety and subclinical worry. The means for the baseline subclinical anxiety group was below the clinical cut-offs on the PSWQ (M = 52.00; SD = 12.94) and SIAS (M = 29.34; SD = 12.00).

Participants were excluded if they endorsed a severe mental illness (i.e., psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder). Three participants were excluded due to suspected Bipolar Disorder (3 with current or previous treatment for Bipolar Disorder and 1 endorsement of a prior manic episode), or a current anxiety disorder (n = 16). Four participants were also excluded due to currently receiving weekly individual therapy. Finally, 12 participants were excluded due to falling outside the range of subclinical social anxiety on the SIAS or subclinical worry on the PSWQ. Undergraduate participants (n = 55) were compensated for their time with course credit. Community participants (n = 14) received $25.00 in compensation upon completing the one-month follow-up.

Measures

Clinician-administered measures.

Diagnostic assessment.

A clinician administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) – Anxiety Disorder Module (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). The anxiety disorder module of the SCID (First et al., 1995) was be administered to assess for the presence of current or past anxiety disorder diagnoses in the sample. The SCID was administered by doctoral students who received extensive training in SCID administration. This training included reviewing the SCID training tapes, observing taped and live SCID administrations, and conducting SCID interviews with a trained interviewer. Throughout the process, interviewers receive feedback until they demonstrate high reliability.

Impairment.

Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI). The CGI (Guy, 1976) is a widely used clinician-rated measure of global impressions of symptom severity. The CGI asks clinicians to rate the severity of symptoms on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (normal, not at all ill) to 6 (among the most extremely ill patients). The CGI displays good inter-rater reliability (Lyons, Reardon, Cukrowicz, Reeves, & Joiner, 2002). It also has been shown to display good concurrent validity and internal consistency in populations with anxiety and depression diagnoses (Leon, Shear, Klerman, & Portera, 1993). The CGI was used to assess for change in overall level of impairment at the one-week check-in and one-month follow-up.

Self-report questionnaires.

Screening.

The Anxiety and Depression Detector (ADD; Means-Christensen, et al., 2006) is a 5-item scale designed to screen for individuals with anxiety disorders and depression. The 5 scale items assess for the following disorders: (1) panic disorder, (2) post-traumatic stress disorder, (3) social anxiety disorder, (4) generalized anxiety disorder, and (4) depression. Respondents are asked to indicate whether (Yes or No) they experienced symptoms associated with each disorder over the past three months. Two-items, the SAD item and GAD item were utilized as an initial screen to identify individuals that may be eligible for the present study. The two items are as follows: (1) Would you say that being anxious or uncomfortable around other people has been a problem for you? and (2) Would you say that you have been bothered by “nerves” or feeling anxious or on edge?

Demographics.

An experimenter developed Demographics Questionnaire (DQ) form was used to gather demographic information, mental health history, and family history of mental health disorders.

Generalized anxiety (worry).

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990) is a 16-item (e.g., My worries overwhelm me) self-report questionnaire that asks respondents to indicate the degree to which an item is typical of them on a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Not at all typical of me; 5 = Very typical of me). The PSWQ has been shown to have sound psychometric properties across clinical and college samples (Meyer et al., 1990). The PSWQ was used in the present study to measure generalized anxiety and worry. The PSWQ demonstrated adequate reliability at baseline (α = .78) and Month 1 (α = .80).

Social anxiety.

The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1989) is a self-report scale assessing the level of fear in social situations involving interaction with others. The SIAS consists of 20-items (i.e., “I have difficulty talking with other people.”) in which respondents rate the degree to which an item is characteristic them on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all characteristic or true of me, 4 = extremely characteristic or true of me). The SIAS has been found to be a reliable measure of social anxiety, exhibiting good convergent and discriminate validity (Brown et al, 1997; Heimberg et al. 1992). The SIAS was used in the present study to measure social anxiety. The SIAS demonstrated good reliability at baseline (α = .85) and Month 1 (α = .86).

Safety aids.

The Safety Aid Scale (SAS; Korte & Schmidt, 2014) is a 79-item scale developed by our lab to assess for safety aid utilization. Respondents are asked to indicate the degree to which they engage in a particular safety aid to reduce their anxiety. Ratings are made on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never or rarely, 4 = almost always). The SAS was used to assess for change in safety aid use from pre-intervention to the one-week check-in and the one-month follow-up. The SAS demonstrated excellent reliability at baseline (α = .94) and Month 1 (α = .96)

Perfectionism.

Perfectionism was assessed using the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost, Marten, Lahart & Rosenblate, 1990). The FMPS provides a total score and six subscales for a multidimensional assessment of perfectionism including: Concern over Mistakes, Personal Standards (PS), Parental Expectations, Parental Criticism, Doubts about actions, and Organization. The FMPS total score was used in the present study. The FMPS demonstrated excellent reliability at baseline (α = .91) and adequate reliability at Month 1 (α = .76).

Procedure

Screening Appointment.

Upon arrival, participants first read and signed an informed consent form that ensures confidentiality, thoroughly outlines their proposed study involvement, and emphasizes that the participant may discontinue their participation at any time, for any reason and at absolutely no penalty. They then completed the SCID and a self-report battery of questionnaires to determine their eligibility. Participants that did not meet the inclusionary criteria, were debriefed, thanked for their time and dismissed from the study. Those who met inclusionary criteria were randomly assigned to one of the two intervention conditions either the Safety Aid Fading and Eliminating Intervention (SAFE) condition or the Health Education and Adaptive Living (HEAL; see description of intervention conditions) condition and completed either the SAFE or HEAL intervention session.

Intervention Appointment.

Upon arrival to the intervention appointment, participants first completed the self-report measures (see Table 1) and the SCID diagnostic interview. The participants then completed the intervention session (i.e., SAFE or HEAL) with the same clinician. Participants were provided with an intervention binder containing materials from the intervention session, homework forms, and extra reading materials. Following completion of the intervention, the participants completed the post-intervention questionnaires and were scheduled for their one-week check-in and one-month follow-up appointments and given a reminder card for both the appointments.

Table 1.

Descriptives of the primary outcome measures among participants in the SAFE and HEAL groups

| Measure | Intervention Session |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 1 | Month 1 | Baseline | Week 1 | Month 1 | |

| SAFE Group (n = 26) | HEAL Group (n = 27) | |||||

| SIAS | 29.3 (13.2) | 25.4 (13.3) | 19.8 (10.4)* | 29.3 (11.1) | 26.5 (10.2) | 24.0 (8.4) |

| PSWQ | 57.0 (9.3) | 48.9 (13.2)* | 43.8 (10.0)* | 47.4 (14.2) | 46.3 (12.9) | 46.7 (12.7) |

| CGI | 2.4 (.72) | -- | 1.5 (.66)** | 1.8 (.66) | -- | 2.0 (.76) |

Note. SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; CGI = Clinician Global Impressions. SAFE = active condition, HEAL = control condition * = significant between group differences from baseline to Week 1 and baseline to Month 1;

p <.01;

p < .05.

One-Week Check-In Appointment.

An e-mail reminder was sent to the participants one day before their one-week check-in appointment reminding them of their appointment and to complete their safety aid homework forms. Upon arrival at the ABHC offices, participants were directed to an individual testing room and completed the week-one follow-up self-report questionnaire battery (see Table 1). After completing the questionnaires, the participant meet with the therapist that administered the intervention for a brief check-in. During the check-in, the homework forms (safety aids forms for the SAFE group, health monitoring forms for the HEAL group) were collected. They also had the opportunity to ask the clinician questions they had about continuing to fade their safety aids (for the SAFE group) or about monitoring their health behaviors (HEAL group) over the following month. Participants received four weekly homework forms (one to use each week) to complete over the one-month follow-up period. Before leaving, the participant was reminded of their scheduled one-month follow-up appointment.

One-Month Follow-Up Appointment.

A nearly identical procedure was employed in the one-month follow-up as was used in the one-week check-in appointment. E-mail reminders were sent to the participants one week and one day before their one-month follow-up appointment. Upon arrival at the ABHC offices, participants were directed to an individual testing room and the clinician administered the SCID-Anxiety Disorder Module to assess for the presence or absence of anxiety disorder diagnoses. In approximately half of the participants, the clinician who administered the baseline SCID and performed the intervention also administered the SCID at Month 1. The participant also completed the follow-up self-report questionnaires. The homework forms (safety aids forms for the SAFE group, health monitoring forms for the HEAL group) were also collected. Following the completion of the self-report questionnaires, participants were debriefed and provided with the opportunity to ask any questions they had about the study.

Description of experimental conditions.

SAFE active group.

The SAFE transdiagnostic intervention was adapted from the F-SET manual used by Schmidt and colleagues (2012). This intervention was developed to closely model the F-SET manual, which utilizes the educational and behavioral techniques that are commonly employed in the treatment of individuals with anxiety disorders. The SAFE intervention was designed as a two-hour intervention session to ensure the intervention would be relatively brief while also providing enough time to cover the key topics in the F-SET manual. The one-session design also enhances the portability of the intervention and makes it comparable to other one-session preventative interventions (e.g., Keough & Schmidt, 2012). The intervention session was separated into two parts. The first part of the intervention session focused on providing psychoeducation about anxiety. The cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety was explained. In particular, participants were informed about how maladaptive thoughts and behaviors contribute to and potentially maintain their anxiety. Participants were also informed of the emotional processing model of anxiety and learn to identify their false alarms to various stimuli. The session then transitioned to the second part of the session focusing on safety aids. Consistent with the F-SET protocol, the participants learned to identify and fade their false safety aids. For example, a participant with subclinical social anxiety who reported an avoidance of speaking in class due to a fear of negative evaluation learned to fade this behavior by beginning to speak in class. An individualized plan was created that included beginning to speak in class once a day, then progressing to two times a day, until they no longer fear speaking up in class. Further, a participant with subclinical worry, engaging in the use of procrastination to reduce their worry, would be instructed to begin working on their tasks that they have been putting off by first starting to work on it for five minutes a day, then 10 minutes, then 30 minutes and so on until the task is completed. Another key component of F-SET is the utilization of antiphobic exercises. Antiphobic exercises are behaviors that directly oppose the participant’s phobic tendencies (i.e., doing the opposite of what they fear) to provide disconfirming evidence of the false threats that play a role in maintaining their anxiety symptoms. For example, someone with a fear of “looking foolish” may be instructed to trip and fall when walking in front of someone. The therapist helped the participants design antiphobic exercises and fading exercises for the safety aids reported during the session to ensure the participants would know how to fade their behaviors and engage in the antiphobic exercises once they leave the session. The SAFE session lasted for approximately two hours. The participants were provided with safety aid self-monitoring forms to track their progress over the one-week check-in and one-month follow-up appointments.

HEAL control group.

To control for differences in session time from the experimental and control groups, the control participants received health-focused psychoeducation from the same therapist providing the active intervention group. The control condition took place over one session and lasted for approximately two hours. During the session, participants met with the clinician who presented information regarding the importance and benefits of a healthy lifestyle and were then provided guidelines to achieve a healthy lifestyle. The therapist discussed with the client how to monitor their own daily health habits and daily-monitoring forms were provided to the participant. They were instructed to use the forms daily for the next month.

Results

Data Analytic Plan

Before conducting analyses, the data underwent a screening process to ensure they were entered accurately (e.g., data-entry errors, missing data). The data was examined for variations in normality including the use of leverage tests in SPSS to assess for univariate and multivariate outliers, examining the data for issues of multicollinearity (e.g., multiple R values above .80), and examining residual scatter plots to assess for non-normality (e.g., skew and kurtosis) of the dependent variables. See Table 1 for the descriptives of the primary outcome measures among participants in the SAFE and HEAL groups.

Primary outcome measures.

To examine the primary hypotheses that experimental group will predict changes in social anxiety symptoms (SIAS), worry (PSWQ), and levels of impairment (CGI), we computed a series of linear regression equations using experimental condition (SAFE, HEAL) as the predictor and either the Week 1 or Month 1 total scores on the SIAS, PSWQ, or CGI entered as the dependent variable. Baseline scores on the SIAS, PSWQ, or CGI were entered as a covariate in the respective regression equation to control for baseline differences in these variables. We also conducted mediation analysis examining whether Week 1 SAS scores would mediate the association between experimental group and either the Month 1 SIAS or Month 1 PSWQ scores.

Mediation analyses.

To examine the prediction that changes in safety aid utilization mediates the effects of the intervention on the anxiety symptoms at the one-week post-intervention check-in and the one-month follow-up, a series of mediation models were computed. Mediation analyses were conducted using PROCESS, a recently developed computational tool for SPSS and SAS to test mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling (Hayes, 2012). PROCESS is able to perform the specialized tasks for mediation analyses from classic mediation approaches (Baron & Kenny, 1986) and modern mediation approaches such as SOBEL (Preacher & Hayes, 2004), PRODCLIN (MacKinnon et al., 2007), and RMEDIATION (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). However, PROCESS is able to produce many of the computations from earlier mediation programs while expanding the number of mediation and moderation analyses that can be conducted. PROCESS also provides estimates of model coefficients using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, produces direct and indirect effect estimates in mediation, and generates bias corrected and percentile based bootstrapped confidence intervals for indirect effects in mediation models. Consistent with Hayes (2012), mediation was deemed to be statistically significant if the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effect does not include zero. Mediation was confirmed when the indirect path of the “x” variable (i.e. intervention condition) to the “y” variable (i.e., post-intervention symptoms) was mediated by the “m” variable (i.e., change in safety behavior utilization using the SAS total score, at the Week 1 and Month 1 follow-ups). Separate mediation analyses were conducted for safety aid utilization (SAS) and a mediator in the association between experimental condition and either the SIAS or PSWQ total scores. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess for group differences in demographic variables at baseline. No significant differences were observed.

Primary Outcomes.

Social anxiety symptoms.

First, we examined the between group differences in the SIAS total score. Consistent with predictions, results revealed significant reductions in the SIAS total score at Month 1 with the regression model accounted for 15.1% of the variance (F (2, 44) = 5.10, p < .01), with the SAFE group having significantly lower scores on the SIAS at Month 1 than the HEAL control group (ß = .30, p < .05). Specifically, The SIAS total score was reduced by 34% in the SAFE group from baseline to Month 1 (29.29 to 19.84) as compared to 18% in the HEAL group (29.35 to 24.00). However, there were no significant group differences in the SIAS total score at Week 1 (p = ns).

Worry symptoms.

We also examined the between group differences in the PSWQ total score. Consistent with predictions, the results revealed significant between group differences in the PSWQ total score at Week 1 with the regression model accounting for 59.4% of the variance (F (1, 49) = 37.63, p <.001, ß = .25, p < .05), reflecting a 14% reduction in worry in the SAFE group from baseline to Week 1 (57.03 to 48.92) as compared to 2% reduction in worry in the HEAL group (47.15 to 46.32). Further, a between group difference in worry was also observed at Month 1 with the regression model accounting for 14.0% of the variance (F (1, 48) = 4.98, p <.05, ß = .30, p < .05), reflecting a 23% reduction in worry in the SAFE group from baseline to Month 1 (57.93 to 44.63) as compared to 1% reduction in worry in the HEAL group (47.15 to 46.72).

Impairment.

We also examined the between group differences in the CGI from baseline to Month 1. Consistent with predictions, there was a significant between group difference in level of impairment at Month 1. The regression model accounted for 38.2% of the variance (F (2, 44) = 15.24, p < .0001), with the SAFE group having significantly lower scores on the CGI at Month 1 than the HEAL control group (ß = .54, p < .0001).

Mediation Models.

Simple mediation was used to examine the two main hypotheses of the study: (1) that a reduction in safety aid use (SAS) would partially mediate the association between experimental condition and the primary outcome measures (SIAS, PSWQ) at Week 1 and Month 1. The experimental condition was used as the predictor (X), the SAS was used as the mediator (M), and the Week 1 or Month 1 SIAS, or PSWQ scores were was used as the criterion (Y) variable in the mediation model performed in PROCESS. Baseline scores on the SAS and the SIAS, PSWQ, and CGI were entered as covariates in the respective mediation models to control for baseline differences.

First, we computed a test of simple mediation to examine the prediction that safety aids utilization at Week 1 (SAS) would mediate the association between experimental group and SIAS total score at Week 1. The total effect model was significant accounting for 41.4% of the variance (F (4, 51) = 10.71, p < .001). The direct effect of experimental group on Week 1 SIAS total score was significant (coefficient = .58, SE = .10, t = 5.63, p < .0001). Consistent with predictions, safety aid utilization (Week 1 SAS) mediated the association between experimental group and Week 1 SIAS total score (coefficient = 2.20, SE = 1.46). The 95 % bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval of the indirect effect did not include zero (.09, 5.70), indicating that there was a significant indirect effect of the experimental condition (SAFE, HEAL) on Week 1 social anxiety scores (SIAS total score) that was mediated by safety aid utilization (SAS) at Week 1. We also performed a test of simple mediation using the Month 1 total scores on the SIAS and SAS. Contrary to predictions, safety aid utilization was not a significant mediator in the association between experimental group and Month 1 follow-up as the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval for the indirect effect included zero (−1.97, 2.07). Further, the mediation analysis examining the Week 1 SAS scores as a mediator in the association between experimental group Month 1 SIAS was not significant.

Next we computed these same mediation models as above using the PSWQ. We computed a test of simple mediation to examine the prediction that safety aids utilization at Week 1 (SAS) would mediate the association between experimental group and PSWQ total score at Week 1. Once again, the total effect model was significant accounting for 67.69% of the variance (F (4, 39) = 23.52, p < .0001). The direct effect of experimental group on Week 1 PSWQ total score was significant (coefficient = .66, SE = .09, t = 6.99, p < .0001). Consistent with predictions, safety aid utilization at Week 1 (SAS) mediated the association between experimental group and Week 1 PSWQ total score (coefficient = 2.42, SE = 1.78). The 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval of the indirect effect did not include zero (.14, 7.89), indicating that there was a significant indirect effect of the experimental condition (SAFE, HEAL) on Week 1 worry scores (PSWQ total score) that was mediated by safety aid utilization (SAS) at Week 1. We also performed a test of simple mediation using the Month 1 total scores on the PSWQ and SAS. Consistent with the results on the Month 1 SIAS, safety utilization was not a significant mediator in the association between experimental group and Month 1 PSWQ follow-up as the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval for the indirect effect included zero (−3.09, 2.41). Further, the mediation analysis examining the Week 1 SAS scores as a mediator in the association between experimental group Month 1 PSWQ was not significant.

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine the use of a transdiagnostic preventative intervention for individuals with subclinical anxiety (SAFE). Specifically, the SAFE intervention was adapted from an established transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety (Schmidt et al., 2012; Ricarrdi, Korte, & Schmidt, 2017) and capitalizes on the strengths of transdiagnostic treatments by creating a parsimonious, easy-to-use intervention, designed to treat the full range of presenting anxiety symptoms. The present study provided initial validation of the SAFE intervention in a sample of individuals with subclinical or higher levels of anxiety. In particular, the results demonstrated the efficacy of the SAFE transdiagnostic intervention in reducing symptoms of worry, social anxiety, and global levels of impairment. Further, we provided evidence for the reduction in social anxiety and worry symptoms being mediated by reduction in safety aid utilization. Taken together, these findings offer support for the ability to use a brief transdiagnostic approach to reduce symptoms of anxiety in those with subclinical levels of anxiety.

The present study had several strengths and important findings to highlight. First, the current investigation is the first to establish the preliminary efficacy of a transdiagnostic preventative intervention in reducing subclinical or higher levels of anxiety. Prior research has supported the ability to reduce symptoms of a specific anxiety disorder such as panic attacks (Dadds et al., 1997; Dadds et al., 1999; Feldner et al., 2008; Gardenwartz & Craske, 2001) or vulnerability factors associated with anxiety disorders, such as AS (Keough & Schmidt, 2012; Korte & Schmidt, In press; Smits et al., 2008). However, the present study is the first to use a transdiagnostic approach and demonstrate the ability to reduce two distinct anxiety symptom clusters, social anxiety and worry.

Second, the results also revealed a distinct pattern when comparing the symptom reduction in social anxiety. Interestingly, between group differences in worry and levels of impairment emerged as early as Week 1, whereas between group differences in social anxiety were not significant until Month 1. This may suggest that worry in more responsive to the intervention than social anxiety. Third, a key strength of the present study is the finding that the symptom reduction in social anxiety, worry, and impairment were significant at the Month 1 follow-up. Although the intervention effect sizes observed for the between group differences were not large and ranged from small (d = .10) to moderate (d = .41), the maintenance of symptom reduction at Month 1 demonstrates that the symptom reduction observed in the study is not a transient change, but it is a durable reduction in anxiety that endures beyond post-intervention.

Further, the specificity of safety aids utilization as a mediator provides preliminary evidence of the underlying mechanisms associated with the reduction of social anxiety and worry during the course of the intervention. This consistent with prior work examining mediators of symptom reduction when using F-SET (Ricarrdi, Korte, & Schmidt, 2016). It is also interesting to note that the change in safety aid utilization was significant a Week 1; however, it was not significant at Month 1. Although preliminary, this finding may suggest that reduction in safety aids may be a more potent underlying mechanism early in the course of symptom reduction, whereas other mediators may be more important for the maintenance of symptom reduction over time.

Finally, although anecdotal, the nature of the SAFE intervention highlighted that a sizable proportion of individuals using alcohol (e.g., 54.5% endorsed use of alcohol to reduce anxiety) and other substances (e.g., 22.8% endorsed use of cannabis or other substances) as a coping mechanism to reduce their anxiety. As such, safety aid fading for a number of these individuals targeted reduction of their alcohol and substance use when in anxiety provoking situations. Given the high comorbidity between anxiety and alcohol and substances use (Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006; Kessler et al, 1996), and the research demonstrating that individuals with elevated anxiety begin using alcohol and substances as a method to cope with anxiety (Back & Brady, 2008; Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004), it seems that extending a transdiagnostic preventive intervention, such as SAFE, for use with individuals with subclinical anxiety and alcohol and substance misuse may be an important next step in the prevention of these highly comorbid disorders.

There are several limitations to consider when evaluating the results of this study. First, the use of a sample that was primarily comprised of students limited the conclusions that could be made from the findings. Although the present study included a subsample of community participants (n = 14; 20%), a majority of the participants were students, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. As such, it is crucial to examine the efficacy of the SAFE intervention for use with other populations. For example, recruiting subclinical participants in other settings, such as primary care settings or emergency room settings, is an important next step. It is known that individuals commonly present to primary care and emergency room settings with complaints of anxiety symptoms, or tend to confuse their anxiety symptoms, such as panic attacks, as being representative of a potential medical illness (e.g., heart attack; Lowe et al. 2002; Roy-Byrne et al. 2005). Thus, primary care and emergency room settings are ideal for identifying individuals who are at elevated risk for developing an anxiety disorder and to test the efficacy and implementation of the transdiagnostic intervention in these settings.

A second limitation was the use of a relatively small sample. Although the sample was large enough to detect between group differences in the primary outcome measures, a larger sample would although for more sophisticated analyses, such as the use of latent growth curve modeling (LGCM; Muthen, 2001) or growth mixture modeling (GMM; Muthen et al, 2001). LGCM or GMM would allow for an examination of the trajectories of change in worry and social anxiety symptoms which may provide greater understanding to the underlying mechanisms involved in the findings.

Another potential limitation of the current study was restricting the recruitment to subclinical levels or higher of social anxiety or worry as opposed to recruiting groups targeting the full range of anxiety symptom clusters. Although the present study targeted individuals with elevated social anxiety and worry, those with other anxiety symptoms clusters (i.e., panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, subclinical PTSD symptoms) were included in the study. It is notable that the SAFE intervention targeted all of the relevant symptoms based on the participant’s symptom presentation, thereby addressing the full range of symptom presentation, as is consistent with a transdiagnostic approach to treatment (Gros, 2014; Schmidt et al, 2012). For example, individuals in the social anxiety group who also presented with panic related concerns received fading exercises for both their social anxiety and panic related concerns. Likewise, individuals meeting the recruitment criteria for the subclinical worry who also had subclinical OCD symptoms received fading exercises targeting their worry and compulsions. As research progresses in this area, it will be important to perform a larger clinical trial to allow for recruitment of additional subclinical anxiety groups (e.g., subclinical panic, subclinical OCD, subclinical PTSD), to fully evaluate the effect of the SAFE intervention on symptoms of anxiety other than the primary social anxiety and worry groups targeted in the present study.

Despite its limitations, the present study adds considerably to the prevention literature by introducing a novel approach to prevention through the development of a transdiagnotic intervention targeting a range of anxiety symptoms clusters with a single intervention protocol. Further, this study provides the initial groundwork for future work in this area. Future research examining the use of transdiagnostic approaches for subclinical symptoms and vulnerability factors has the potential to lead to exciting advances in the prevention of anxiety disorders by addressing a range of presenting anxiety symptoms and other risk factors associated with the prospective development of anxiety disorders, such as AS, thereby improving our ability to provide preventive interventions to at risk individuals in need of early intervention.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA award number F31MH102862-01 and the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health award number D43 TW010543. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Allen N, Korte KJ, Capron DW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2014). A factor mixture modeling investigation of anxiety sensitivity: Evidence for class differences in the prediction of anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 26, 1184–1195. doi: 10.1037/a0037436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aune T & Stiles TC (2009). Universal-based prevention of syndromal and subsyndromal social anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 867–879. doi: 10.1037/a0015813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, & Brady KT (2008). Anxiety disorders and comorbid substance use disorders: Diagnostic and treatment considerations. Psychiatric Annals, 38, 724–729. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20081101-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, & Ehrenreich-May J (2011). The unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator—mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, & Curran PJ (2004). The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychological Methods, 9, 3–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56, 893–897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, & Coffey SF (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00309.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, & Barlow DH (1997). Validation of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 9, 21–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.1.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, & Mancill RB (2001). Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 585–599. DOI: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, & Schmidt NB (2012). Social anxiety and cannabis use: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 26, 297–304. DOI: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 685–716. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF (2006). Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 247–257. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Holland DE, Laurens KR, Mullins M, Barrett PM, & Spence SH (1999). Early intervention and prevention of anxiety disorders in children: Results at 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 145–150. DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Spence SH, Holland D, Barrett PM, & Laurens K (1999). Early intervention and prevention of anxiety disorders: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 627–635. DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon B & Maack DJ (2008). The effects of safety behaviors on the fear of contamination: An experimental investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, & Buchner A (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2008). Prevention of anxiety psychopathology: A critical review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 405–424. DOI: 10.1093/clinpsy/bph098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Zvolensky MJ, Babson KA, Leen-Feldner EW, & Schmidt NB (2008). An integrated approach to panic prevention targeting the empirically-supported risk factors of smoking and anxiety sensitivity: Theoretical basis and evidence from a pilot project evaluating feasibility and short-term efficacy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 1227–1243. DOI: 10.1002/da.20281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M & Williams JB (1994). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM—IV–Patient Edition (Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department; ). [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, & Rosenblate R (1990). Dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. doi: 10.1007/BF01172967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardenwartz CA, & Craske MG (2001). Prevention of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32, DOI: 725–737. 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80017-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis MM, Haaga DAF, & Ford GT (1995). Normative values for the Beck Anxiety Inventory, Fear Questionnaire, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, and Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 7, 450–455. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, (2014). Develop and initial evaluation of Transdiagnostic Behavior Therapy (TBT) for Veterans with affective disorders. Psychiatry Research, 220, 275–282. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W (Ed.). (1976). Clinical Global Impressions. Rockville, MI: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons Reardon M, Cukrowicz KC, Reeves MD, & Joiner TE (2002). Duration and regularity of therapy attendance as predictors of treatment outcome in an adult outpatient population. Psychotherapy Research, 12, 273–285. DOI 10.1080/713664390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RS (1983). An operational classification of disease prevention. RS Public Health Reports, 1983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al. (1999). The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60, 427–435. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.v60n0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable moderation, mediation, and conditional process modeling. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Heimberg RG, Mueller GP, Holt CS, Hope DA, & Liebowitz MR (1992). Assessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Behavior Therapy, 23, 53–73. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80308-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Litz BT, Kim HJ, Davis LL, & Pizzagalli DA (2005). The worried mind: Autonomic and prefrontal activation during worrying. Emotion, 5, 464–475. DOI: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.4.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Korte KJ, & Smits JAJ (2009). Is it beneficial to add pharmacotherapy to cognitive-behavioral therapy when treating the anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 2, 160–175. DOI: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.2.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, & Smits JAJ (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6, 621–632. DOI: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis JH & Telch MJ (1998). Assessment of strategies to manage or avoid perceived threats among panic disorder patients: The Texas Safety Maneuver Scale (TSMS). Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 5, 177–186. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ (2010). Calculating clinically significant change: Applications of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale to evaluate client outcomes in private practice. Clinical Psychologist, 14, 107–111. DOI: 10.1080/13284207.2010.512015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keough ME, & Schmidt NB (2012). Refinement of a brief anxiety sensitivity reduction intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, April 2 DOI: 10.1037/a0027961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlurd MJ, Frank RG, et al. (1996). The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental health disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 17–31. DOI: 10.1037/h0080151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte KJ, Allan NP, & Schmidt NB (2016). Factor-mixture modeling of the PSWQ: Evidence for distinct classes of worry. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 37, 40–47. DOI: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte KJ, & Schmidt NB (2015). The use of motivation enhancement therapy to increase utilization of a preventative intervention for individuals with elevated anxiety sensitivity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39, 520–530. DOI: 10.1007/s10608-014-9668-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korte KJ & Schmidt NB (2014). Development and initial validation of the Safety Aid Scale (SAS). Poster presented at the annual conference of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT), Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Grafe K, Zipfel S, Spitzer RL, Herrmann-Lingen C, Witte S, et al. (2002). Detecting panic disorder in medical and psychosomatic outpatients. Comparative validation of the Hospital anxiety and depression scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire, a screening question and physician’s diagnosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 515–519. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00072-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubke GH, & Muthén B (2005). Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychological Methods, 10, 21–39. DOI: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, & Clarke JC (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 455–470. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus F, Sacadura C, & Clark DM, (2008). Why social anxiety persists: An experimental investigation of the role of safety behaviours as a maintaining factor Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 39, 147–161. DOI: 10.1016/j.btep.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means-Christensen AJ, Sherbourne C, Roy-Bryne P, Craske M, & Stein M, (2006). Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: diagnostic accuracy of the Anxiety and Depression Detector. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28, 108–118. DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 487–495. DOI: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B (2001). Second-generation structural equation modeling with a combination of categorical and continuous latent variables: New opportunities for latent class–latent growth modeling In: Collins Linda M. (Ed); Sayer Aline G. (Ed), (2001). New methods for the analysis of change. Decade of Behavior, (pp. 291–322). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Brown CH, Masyn K, Jo B, Khoo ST, Yang CC, Lioa J (2002). General growth mixture modeling for randomized preventative interventions. Biostatistics, 3, 459–475. DOI: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ (2008). An open trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 39, 242–250. DOI: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36, 717–731. DOI: 10.3758/BF03206553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee R, Craske M, Brown TA, & Barlow DH (1996). Measurement of control over anxiety-related events. Behavior Therapy, 27, 279–293. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80018-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, & McNally RJ (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24, 1–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-7967(86)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, & McNally RJ (1985). Expectancy model of fear In Reiss S & Bootzin RR (Eds.). Theoretical issues in behavioral therapy (pp. 107–121) San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi CJ, Korte KJ, & Schmidt NB (2017). False Safety Behavior Elimination Therapy: A randomized study of a brief individual transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 35–45. DOI: 10/1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Heimberg RG, Brown PJ, Fernandez KC, Blanco C, Schneider FR, & Liebowitz MR (2011). More reason to be straightforward: Findings and norms for two scales relevant to social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 623–630. DOI: 10.1016/j.anxdis.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, & Kagan J (1993). Behavioral inhibition in childhood: A risk factor for anxiety disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1, 2–16. DOI: 10.3109/10673229309017052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Bystritsky A, Katon W, & Sherbourne CD (2005). A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 290–298. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Pusser A, Woolaway-Bickel K, Preston JL, & Norr AM (2012). Randomized controlled trial of False Safety Behavior Elimination Therapy (FSET): A unified cognitive behavioral treatment for anxiety psychopathology. Behavior Therapy, 43, 515–532. DOI: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K, Fitzpatrick KK, Vasey MW, & Richey JA (2007). Anxiety sensitivity amelioration training (ASAT): A longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 302–319. DOI: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV (1983). The anxiety disease. (New York: Scribner; ). [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS & Gaher RM (2005). The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion, 29, 83–102. DOI: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Berry AC, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Behar E, Otto MW (2008). Reducing anxiety sensitivity with exercise. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 689–699. DOI: 10.1002/da.20411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR,...& Cardenas SJ (2007). Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment, 19, 176–188. DOI: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D & MacKinnon DP (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 692–700. DOI: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Bruce SE, Dyck IR & Keller MB (2003). Chronicity, relapse, and illness course of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder: Findings in men and women from 8-years of follow-up. Depression and Anxiety. 17, 173–179. DOI: 10.1002/da.10106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]