As England finds itself in the midst of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the spotlight has rarely been as focussed on public health. Although managing disease outbreaks is one key component of public health, another fundamental purpose is the reduction of health inequalities. These are defined as avoidable, unfair and socially unjust systematic differences in health between different sub-groups of a population.1 They exist across ‘protected characteristics’ enshrined in the Equality Act, as well as other dimensions such as income and educational attainment.2 For example, men and women living in the most deprived areas of England have almost 20 fewer years in good health than those in the least deprived localities.3

Since 2012, the NHS has had a legal duty to reduce inequalities.4 However, the COVID-19 crisis may increase disparities. This article explores the nature of health inequalities relating to the response to COVID-19 by hospital trusts and suggests approaches to reduce them.

Disruption of healthcare for non-COVID-19 patients

Socioeconomically disadvantaged people are more frequent users of healthcare,5 as are the elderly.6 In particular, those in the most deprived decile access emergency services more than twice as often as the least deprived,7 and the Emergency Department is often used for routine care by marginalised groups who find it difficult to access General Practice and other community services.8 Therefore, disruption to elective or emergency care will have disproportionately large negative impacts on these marginalised groups.

In order to release capacity for patients with COVID-19, hospitals in England were instructed to suspend non-urgent clinical services.9 For example, one London teaching hospital has reduced activity by 80%, affecting numerous services including gynaecology, sexual health and paediatrics,10 as well as restricting access to diagnostics such as ultrasound.

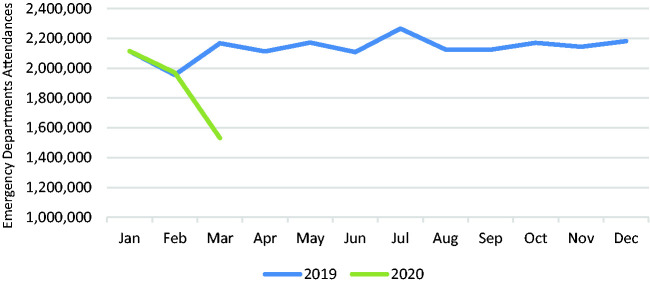

Concurrently, there has been a sharp drop in Emergency Department attendances, with a decline of almost 44% during March11 (see Figure 1), compared to an 11% increase in March last year12 (see Figure 2). While the reasons for this are unclear, it is possible that patients are being deterred by increasing COVID-19 hospitalisations and death rates, associated fear of nosocomial COVID-19 infection and sensitisation to concerns about overburdening NHS services. Public messaging may also have played a part, for example: ‘To protect others, do not go to places like a GP surgery, pharmacy or hospital. Stay at home’.13

Figure 1.

Weekly emergency department attendances, 2020.

Source: Royal College of Emergency Medicine Winter Flow Project 2019/2020.11

Figure 2.

Monthly emergency department attendances in England, Jan 2019 – Apr 2020.

Source: NHS England, A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions 2018-2019.12,42

The steep decline suggests that some patients genuinely in need of medical attention are no longer attending Emergency Departments, in which case they are jeopardising their health. Furthermore, specific concerns have been raised that children and families may not be accessing medical advice and review.14

Both the restriction of non-urgent clinical services and the precipitous decline in Emergency Department attendances will affect marginalised groups disproportionately by restricting access to care6 and therefore exacerbating health inequalities. Hospitals are attempting to mitigate the impact of service reduction by replacing clinic appointments with telephone or video consultations and by offering enhanced support to general practitioners through remote specialist advice from hospital consultants. However, people with a poorer grasp of English or lower health literacy levels may not have their needs met adequately through these methods when compared with traditional face-to-face consultations.8 We therefore propose that innovative methods are considered to facilitate access during the pandemic, such as the clean sites being established for cancer patients,15 and that non-urgent clinical services are restored as soon as it is safe to do so.

In terms of public messaging, although some channels are beginning to nuance advice, such as ‘for life-threatening emergencies, call 999 for an ambulance’, there is an urgent need to communicate clearly and in lay language so that those with emergency health needs should continue to attend Emergency Departments or use other NHS services such as general practices and urgent care centres.

Staff absence and infection control

A vital part of our response to COVID-19 is minimising staff absence. Despite this, testing is only just becoming available and in a recent survey one in five staff reported being off work for coronavirus-related reasons, with the same proportion unable to access appropriate personal protective equipment.16 To address this, NHS employers have been mandated to increase testing to support staff retention,17 provide more comprehensive personal protective equipment18 and clearly communicate pay arrangements for instances of self-isolation. This includes that any absence due to self-isolation should be treated as an absence related to compliance with infection control guidance and should not contribute to sickness absence policy triggers.19

While welcome, these approaches fail to recognise the likely inequality in protection for critical workers who are not directly employed by the NHS. While the focus has been on ensuring availability of clinicians, hospitals need many other support staff in areas such as security, cleaning, portering and catering. These workers access the same clinical areas, may have significant patient contact and without them it would be impossible to deliver health services. However, many NHS trusts do not directly employ these staff groups, who are usually in the lowest pay bands and are more likely to be migrants. As a result, they often do not enjoy equality in pay or terms of employment,20,21 and in particular many outsourcing firms do not provide sick pay for the first three days.22

A consequence of this may be that staff with mild symptoms or who have a symptomatic household member may feel they have no option but to attend work, thereby undermining infection control efforts. This may make the terms of employment unsafe for staff, their families, NHS colleagues and, critically, patients. These concerns are supported by evidence that nosocomial infections are higher in hospitals that have contracted out cleaning services, than those that have not.20 NHS England have instructed that all staff, including outsourced workers, receive full pay during self-isolation,23 but there are concerns that this has not been comprehensively implemented. There is therefore an immediate need to review contractors’ staff policies and processes with regards to COVID-19 testing, personal protective equipment and absence arrangements.

Smoking cessation

In England, there are well-established smoking prevalence gradients across genders (males, 16.8%; females, 13.0%) and deprivation decile (most deprived, 18.1%; least deprived, 10.4%).24 Early data from China show a threefold difference in poor outcomes: while 12.4% of hospitalised smokers were admitted to intensive care, mechanically ventilated or died, among non-smokers this was only 4.7%.25

Although not yet conclusive, it is plausible that smoking is a risk factor for COVID-19 considering higher infection rates in people who smoke for other respiratory illnesses such as influenza.26 Potential infection mechanisms are the repetitive fingers-to-mouth action when consuming tobacco, and sharing smoking materials, e.g. waterpipe mouthpieces.27 In addition, once a patient who smokes has contracted COVID-19, the many adverse effects of smoking on respiration, circulation and other physiological functions are likely to affect outcomes.

The precautionary principle would therefore support raising awareness of smoking cessation services, which in turn may reduce inequalities in infection rates and disease progression.24 Official guidance advises postponing face-to-face smoking cessation clinics during the pandemic,28 but we encourage providers to provide alternative remote services and to promote these tenaciously. For those that continue to use tobacco products, there should be clear targeted messaging about avoiding smoking indoors during either self-isolation or lockdown periods, particularly when others are present and to observe social distancing rules, including not smoking in public groups.29

Finally, younger women and those living in more deprived areas are more likely to smoke during pregnancy.30 Self-reported status results in underestimated smoking prevalence, and carbon monoxide screening is mandated.30 However, to minimise COVID-19 infection risk, carbon monxide screening of pregnant women has been temporarily suspended.31 Nonetheless, it remains vital that maternity services continue to ask women (and their partners) if they smoke or have recently quit, and continue to refer those who smoke for specialist cessation support.

Inaccurate baseline data

Disease incidence and progression for many conditions can vary by ethnicity and COVID-19 may be no different. It is therefore imperative that we rigorously capture baseline data so that we understand the impact of key risk factors on disease prognosis. While ethnicity data are generally accurately captured for white British patients, for minority groups only 60–80% of hospital records capture ethnicity correctly,32 so we risk reaching incorrect conclusions based on flawed data.

We also need to consider NHS Staff: with 1 in 5 NHS staff from ethnic minority groups, and 2 in 5 doctors,33 this is disproportionately high compared to the general population.34 As the first deaths among clinicians are announced with a disproportionate number of deaths in health professionals from minority ethnic backgrounds, there will be intense post hoc scrutiny of systematic differences between groups and whether the NHS adequately protected its staff. How and whether we measure ethnicity matters and it is critical for trusts to do so accurately – both among patients and staff – using nationally recommended categories so that data are meaningful and comparable.35

Moreover, smoking is not currently considered a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 infection.36 This is despite a plausible hypothesis that inhaling chemicals could be associated with lung damage and subsequently poorer COVID-19 outcomes. Many UK hospitals have joined the global RECOVERY trial,37 which could provide a rare insight into the impact on lung health of not just combustible tobacco products but also electronic cigarettes, but only if this is rigorously captured in health records. We support the development of mechanisms to routinely capture such data, such as the one below which is being developed by an NHS hospital in London (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Tobacco and nicotine screening tool.

Source: Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Advance decisions

An advance decision allows people to specify that they refuse a specific type of treatment sometime in the future. Critically it lets people involved in care and treatment – including family members and healthcare professionals – act upon a patient’s wishes if capacity has been lost. Nonetheless, the prevalence of advanced decisions in England is estimated at just 4%,38 perhaps due to a belief it is unnecessary if family members or clinicians have been informed of a patient’s wishes.

Data from Italy show that consistently between 9% and 11% of COVID-19 patients are admitted to intensive care units.39 Early data of confirmed cases admitted to intensive care units in England show inequalities, with patients overwhelmingly older (median age 61 years) and male (7 in 10 patients).40 Nearly 60% were mechanically ventilated within 24 h of admission and of those with recorded outcomes, 871 (51.6%) had died and were 818 discharged from the intensive care unit alive.40

Many marginalised groups, including certain faith groups, prisoners and those experiencing homelessness, experience disadvantage in their end-of-life journey.41 While frontline clinicians will undoubtedly be striving to deliver patient-centred care under extremely difficult circumstances, whether to accept life-sustaining treatment remains a deeply personal decision: time on an intensive care unit is gruelling and can leave survivors, even previously fit-and-well patients, with long-term effects.

Not all eligible patients would want to be admitted to intensive care or receive mechanical ventilation. There is an urgent need for a compassionate national conversation, focussed on those from marginalised groups with and without COVID-19, so that their wishes are formally understood in case they become critically ill or lose capacity. This would allow more patients to be cared for according to their wishes and reduce the intense pressure on frontline clinicians which results from making these decisions in acute settings.

Conclusions

We do not underestimate the threat posed by COVID-19 and we commend the NHS on the swift action taken to expand capacity and reorganise services to help ensure that it can cope. We recognise that difficult choices have been required and that some unintended consequences are inevitable. However, policymakers, managers and clinicians should take pause during this accelerated work to protect the most vulnerable from negative unintended consequences and avoid worsening health inequalities. We believe that hospitals are uniquely placed to support this agenda.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

This article was in part supported by the NW London NIHR Applied Research Collaboration. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care; or Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Guarantor

SC-C.

Contributorship

SC-C and EJM wrote the article. EJM finalised the manuscript. SC-C and AM revised the draft and provided critical feedback. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NW London NIHR Applied Research Collaboration for support.

Provenance

Not commissioned; editorial review

ORCID iD

Azeem Majeed https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2357-9858

References

- 1.Williams E, Buck D and Babalola G. What are health inequalities? The King’s Fund. See https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/what-are-health-inequalities (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 2.NHS England. Monitoring Equality and Health Inequalities: A Position Paper. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/monitrg-ehi-pos-paper.pdf (16 March 2015, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 3.Public Health England. Chapter 5: inequality in health. GOV.UK. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-profile-for-england/chapter-5-inequality-in-health (2017, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 4.NHS England. Guidance for NHS commissioners on equality and health inequalities legal duties. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/hlth-inqual-guid-comms-dec15.pdf (14 December 2015, last checked 26 April 2020).

- 5.Cookson R, Propper C, Asaria M, et al. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health Care in England. Fisc Stud 2016; 37: 371–403. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Propper C, Stoye G, Zaranko B. The wider impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the NHS, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS Digital. Hospital Accident and Emergency Activity 2018 19. See https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-accident--emergency-activity/2018-19# (2019, last checked 26 April 2020).

- 8.MacKichan F, Brangan E, Wye L, et al. Why do patients seek primary medical care in emergency departments? An ethnographic exploration of access to general practice. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e013816–e013816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens S and Pritchard A. Important and urgent – next steps on NHS response to COVID-19. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/20200317-NHS-COVID-letter-FINAL.pdf (2020, last checked 10 April 2020).

- 10.Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. COVID-19 response from Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust – GP communications (Issue two). See https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/Home.aspx (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 11.The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Winter Flow Project 2019/20. See https://www.rcem.ac.uk/RCEM/Quality_Policy/Policy/Winter_Flow_Project/RCEM/Quality-Policy/Policy/Winter_Flow_Project.aspx (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 12.NHS England. A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions 2018-19. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/, https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2018-19/ (2019, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 13.NHS. Self-isolation if you or someone you live with has symptoms. See https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/self-isolation-advice/ (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 14.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Delayed access to care for children during COVID-19: our role as paediatricians - position statement. See https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/delayed-presentation-during-covid-19-position (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 15.Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, NHS. Clinical guide for the management of essential cancer surgery for adults during the coronavirus pandemic. 001559, https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/04/C0239-Specialty-guide-Essential-Cancer-surgery-and-coronavirus-v1-70420.pdf (7 April 2020, last checked 9 April 2020).

- 16.Royal College of Physicians. COVID-19 and its impact on NHS workforce. See https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/covid-19-and-its-impact-nhs-workforce (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 17.Pritchard A, Powis S and Marsh S-J. COVID-19 testing to support retention of NHS staff, https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/covid-19-testing-and-staff-retention-letter-29-march-2020.pdf (2020, last checked 27 April 2020).

- 18.Public Health England. COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE). See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 19.The NHS Staff Coucil. NHS Staff Council Statement on Covid-19. See https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/NHS-Staff-Council---Guidance-for-Covid-19-Feb-20.pdf?la=en&hash=70C909DA995280B9FAE4BF6AF291F4340890445C (2020, last checked 27 April 2020).

- 20.Elkomy S, Cookson G, Jones S. Cheap and Dirty: The Effect of Contracting Out Cleaning on Efficiency and Effectiveness. Public Adm Rev 2019; 79: 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardiner T. At last our hospital’s cleaners, caterers and porters work for the NHS again. The Guardian, 5 February 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/05/hospital-cleaners-nhs (5 February 2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 22.GMB Union. Coronavirus: NHS trusts must ensure sick pay for outsourced staff. See https://www.gmb.org.uk/news/coronavirus-nhs-trusts-must-ensure-sick-pay-outsourced-staff (2020, last checked 16 April 2020).

- 23.NHS Employers. Self-isolation. See https://www.nhsemployers.org/, http://www.nhsemployers.org/covid19/staff terms and conditions/self isolation (2020, last checked 16 April 2020).

- 24.NHS Digital. Statistics on Smoking, England - 2019. See https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2019 (2019, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 25.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Lawrence H, Hunter A, Murray R, et al. Cigarette smoking and the occurrence of influenza – Systematic review. J Infect 2019; 79: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Tobacco and waterpipe use increases the risk of suffering from COVID-19. See http://www.emro.who.int/tfi/know-the-truth/tobacco-and-waterpipe-users-are-at-increased-risk-of-covid-19-infection.html (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 28.British Medical Association, Royal College of General Practitioners. RCGP Guidance on workload prioritisation during COVID-19. Version 5, 23 March 2020.

- 29.Cabinet Office. Staying at home and away from others (social distancing). See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 30.Public Health England. Health of women before and during pregnancy: health behaviours, risk factors and inequalities, London: Public Health England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. Protecting smokers from COVID-19, https://www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_COVID-19_18.03.20.php (2020, last checked 27 April 2020).

- 32.Saunders K. Do NHS records reflect patient ethnicity? See https://www.statslife.org.uk/health-medicine/1940-do-nhs-records-reflect-patient-ethnicity (2014, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 33.NHS Digital. NHS Workforce Statistics - March 2019 (Including supplementary analysis on pay by ethnicity). See https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/nhs-workforce-statistics---march-2019-provisional-statistics (2019, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 34.GOV.UK. Population of England and Wales. See https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest (2019, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 35.Office for National Statistics. Ethnic group, national identity and religion. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/measuringequality/ethnicgroupnationalidentityandreligion (2016, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 36.Public Health England. Guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-social-distancing-and-for-vulnerable-people/guidance-on-social-distancing-for-everyone-in-the-uk-and-protecting-older-people-and-vulnerable-adults (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 37.Department of Health and Social Care. World’s largest trial of potential coronavirus treatments rolled out across the UK. See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/worlds-largest-trial-of-potential-coronavirus-treatments-rolled-out-across-the-uk (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).

- 38.Public Policy Institute for Wales. Increasing understanding and uptake of Advance Decisions in Wales, Public Policy Institute for Wales, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remuzzi A and Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? The Lancet 2020; 395: 1225–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre. ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care, London: Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Care Quality Commission. A different ending: Addressing inequalities in end of life care, Newcastle Upon Tyne: Care Quality Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.NHS England. A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions 2019-20. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2019-20/ (2020, last checked 15 April 2020).