Abstract

Using in situ generated H2O2 is potentially an effective approach for benzyl alcohol selective oxidation. While the microporous titanium silicate (TS-1) supported with Pd is promising for selective oxidation, the Pd particles are preferentially anchored on the external surface, which leads to the problems such as non-uniform dispersion and low thermal stability. Here, we prepared a Pd@HTS-1 catalyst in which the Pd subnanoparticles were encapsulated in the channels of the hierarchical TS-1 (HTS-1), for benzyl alcohol selective oxidation with in situ produced H2O2. We find that the oxidation rate of benzyl alcohol by in situ H2O2 over the Pd@HTS-1 is up to 4268.8 mmol h–1 kgcat–1, and the selectivity of benzaldehyde approaches 100%. In contrast to the conventional Pd/HTS-1, the present Pd@HTS-1 benefits the benzyl alcohol selective oxidation due to the increased dispersion of Pd particles (forming uniformly dispersed subnano-sized particles), as well as the confinement effect and hierarchical porosity of the HTS-1 host. We further suggested that hydrogen peroxide produced in situ from the molecular hydrogen and oxygen over the Pd sites can be spilled over to the framework Ti4+ sites, forming the Ti-OOH active species, which selectively oxidizes the chemisorbed benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde on the Pd sites.

1. Introduction

Titanium silicate (TS-1) is a framework-substituted heterogeneous titanium catalyst.1 It exhibits unique redox selectivity in catalytic selective oxidation reaction especially when H2O2 is used as an oxidizer.2−4 The chemical reaction process involving TS-1/H2O2 heterogeneous catalytic system for oxidation is environmentally friendly. The TS-1/H2O2 catalytic selective oxidation system is attractive for industrial applications because it has higher selectivity, clean reactions, and cost effective. However, the commercial H2O2 is produced via the anthraquinone process,5,6 it includes the successively consecutive hydrogenation/oxidation of the alkylated anthraquinone intermediate dissolved in a composite of organic solvents and reclaims H2O2 by liquid–liquid extraction, immediately concentrating to a final product. The multistep process of H2O2 production consumes much energy and results in a substantial amount of waste. Also, the storage, transport, and disposal of the concentrated H2O2 bring additional costs and risks concerning safety. Compared to the anthraquinone process, the direct H2O2 synthesis and in situ reaction to an oxygenated target will become a promising process owing to the apparent advantages of high efficiency, conserve energy, and reduced emissions.

The very first process of producing H2O2 from hydrogen and oxygen was reported by Henkel and Weber in 1914.7 The Pd-based catalysts showed the optimal activity for the direct H2O2 synthesis.8−13 Noble metal loaded on the porous support is a valuable catalyst for industrial application, such as TS-1 or TiO2 supported Pd (or Au) nanoparticles for propene epoxidation with H2/O2.14,15 The Au-Pd/TS-1 was also found to have high activity in benzyl alcohol selective oxidation via generated H2O2 in situ.16 However, these methods usually involve loading the metals on the external surface of the support, especially for the microporous materials. The active metal particles are generally not dispersed uniformly and have low thermal stabilities, which limits the applications in high-temperature catalysis fields. The encapsulation of metal particles during the syntheses of microporous zeolite materials is an effective method to improve their stability against thermal sintering,17−22 yielding a uniform, stable, and highly dispersed subnano catalyst.

Diffusion is critical to oxidation reaction with H2O2. Slow diffusion inside the pores of the porous support limits the mass transfer of reactants and products, which restricts the rate of reaction and results in overreactions and leading to by-products. Thus, in situ synthesis of hydrogen peroxide and creation of larger pores can improve the diffusion and lead to better accessibility of the active sites. Our previous studies showed that the creation of mesopores within TS-1 could significantly improve the catalytic performance in producing hydrogen peroxide from hydrogen and oxygen.23 Therefore, we believe that the combination of creating hierarchical pore structures in TS-1 and direct H2O2 synthesis will allow us to improve mass transfer for the benzyl alcohol oxidation and selectivity for benzaldehyde.

In this work, we report a tandem reaction of in situ hydrogen peroxide and benzyl alcohol selective oxidation over Pd@hierarchical titanium silicalite catalysts. We prepared Pd@HTS-1 by an in situ Pd encapsulation method and Pd/HTS-1 by incipient wetness impregnation. The catalysts were systematically characterized by various methods, including X-ray powder diffraction (PXRD), infrared spectroscopy (IR), nitrogen adsorption electron microscopy, temperature-programmed desorption (TPD), and different-size nitro compound hydrogenation. These results indicate that the Pd particles were highly dispersed and successfully encapsulated within the channels of HTS-1 for the Pd@HTS-1 catalyst. The catalytic performance of tandem reaction in situ hydrogen peroxide selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol over Pd@HTS-1 and Pd/HTS-1 was compared. Furthermore, the reaction mechanism of the tandem reaction was investigated via integrating characterization and catalytic performance.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

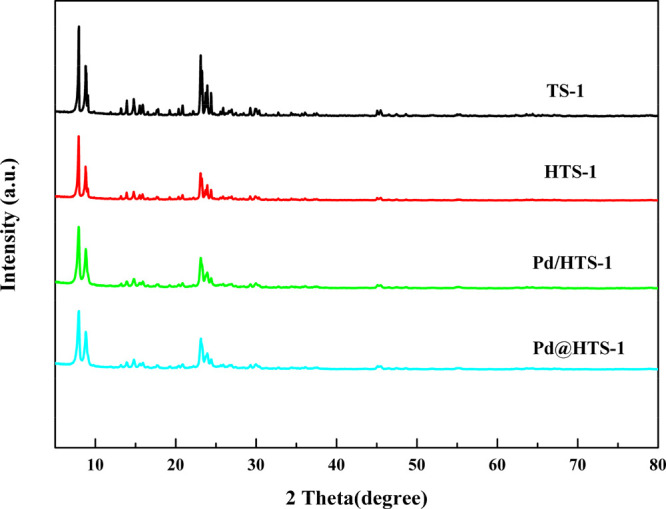

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of TS-1, HTS-1, Pd/HTS-1, and Pd@HTS-1. Notably, all curves show homologous characteristic peaks at 2θ = 7.9°, 8.9°, 23.1°, 23.9°, and 24.4°, which indicates that all four catalysts are a well-crystallized structure (topological structure MFI, defined by the Structure Commission of the International Zeolite Association).24−28 Meanwhile, no diffraction peak of crystalline metal Pd was clearly observed for Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts. The existence of metallic Pd was confirmed by ICP-OES, indicating that the average sizes of Pd particles are very small and well dispersed within the framework of the support or low loading.29 The XRD patterns of four catalysts are essentially the same, which indicate that the different preparation methods yielded the zeolites with the same framework topology.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction patterns of TS-1 and Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts.

In FT-IR spectra (see Figure 2), all samples show the absorption bands at 1230, 1100, 970, 800, 550, and 455 cm–1, which belong to the highly crystalline MIF structure. Among them, the sharp peak at 1230 cm–1 is due to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si, and the relatively weaker band at 970 cm–1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching mode of Si-O-Ti into the zeolite framework.30

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of TS-1 and Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts.

The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of the TS-1 and Pd-modified TS-1 are shown in Figure 3a. The type I isotherm of TS-1 confirms that the material is microporous. Meanwhile, typical irreversible type-IV isotherms with an H1 hysteresis loop were observed for HTS-1 and modified-HTS-1 samples, suggesting the presence of the mesoporous structure. Using the BJH method, Figure 3b shows pore size distribution of four samples. Moreover, the pore sizes of HTS-1 and Pd/HTS-1 are 12 nm, and the pore size distribution of Pd@HTS-1 is centered at about 8 nm.

Figure 3.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (a) and the pore size distribution (b) of TS-1 and Pd- modified TS-1.

The surface area and pore structure are summarized in Table 1. The micropore volume of HTS-1 is 0.08 cm3 g–1, the meso/macropore volumes of three modified TS-1 samples are roughly 0.45 cm3 g–1. The presence of mesopores is attributed to the intraparticle gaps, indicating the coexistence of inherent micropores and meso/macropores. Furthermore, an interconnection exists in among the micro- and meso/macropores.31 Thus, we deem that three modified TS-1 samples have hierarchical pore structures.

Table 1. Textural Properties of Hierarchical Porous TS-1 and Pd-Modified TS-1 Catalysts.

| surface area (m2 g–1) | pore volume (cm3 g–1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | BET | micropore | external | microporea | meso + macrob |

| TS-1 | 434.3 | 243.9 | 190.4 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| HTS-1 | 485.8 | 155.6 | 330.2 | 0.08 | 0.47 |

| Pd/HTS-1 | 451.5 | 162.7 | 288.8 | 0.08 | 0.44 |

| Pd@HTS-1 | 470.5 | 160.3 | 310.2 | 0.08 | 0.45 |

Micropore volume was estimated using the t-plot method.

The mesopore + macropore volume was calculated from the amount of N2adsorbed at P/P0 = 0.99.

Moreover, the encapsulation of Pd particles in the HTS-1 results in a slight decrease in the surface area. The surface area dropped from 485.8 m2 g–1 for pure HTS-1 to 451.5 m2 g–1 for Pd/HTS-1 and 470.5 m2 g–1 for Pd@HTS-1. It might be due to that some channels of the zeolites are blocked by the Pd nanoparticles during the synthesis process.

The stability of metal clusters is a key issue for their applications in high-temperature catalysis fields due to the metal cluster migration and coalescence by Ostwald ripening. The encapsulation of metal particles in the microporous zeolitic materials can improve their stability against thermal sintering.17−22 Owing to high thermal stability and a confining environment, zeolitic materials promise to be potential supports for preparing various metal catalysts. However, during the reaction or harsh thermal treatments, the active metal particles, which are located on the external surface of zeolites prepared by wet impregnation or ion exchange, may aggregate to form bigger particles, bringing about a decrease in activity.32−35 Therefore, the thermal stabilities of Pd@HTS-1 and Pd/HTS-1 were evaluated and compared after high-temperature oxidation/reduction/oxidation treatments to emulate conditions used to regenerate metal catalysts.

After O2/H2/O2 thermal treatments at 500/400/500 °C for 4/2/6 h, we obtained six different catalysts (Pd/HTS-1-O, Pd/HTS-1-OR, Pd/HTS-1-ORO, Pd@HTS-1-O, Pd@HTS-1-OR, and Pd@HTS-1-ORO, respectively). For Pd/HTS-1-O, it means that Pd/HTS-1 was conducted thermal treatment with O2 at 500 °C for 4 h, and for Pd/HTS-1-OR, it means that Pd/HTS-1 was conducted continuous thermal treatments (O2 at 500 °C for 4 h, H2 at 400 °C for 2 h). Pd/HTS-1-ORO was obtained after continuous thermal treatments (O2 at 500 °C for 4 h, H2 at 400 °C for 2 h, and O2 at 500 °C for 6 h). The other three catalysts (Pd@HTS-1-O, Pd@HTS-1-OR, and Pd@HTS-1-ORO) were also obtained by similar thermal treatments. Figure 4d,e,f shows Pd particles size distributions of Pd@HTS-1 (4d-Pd@HTS-1-O, 4e-Pd@HTS-1-OR, and 4f-Pd@HTS-1-ORO). The HRTEM images and Pd particle size distributions of the Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts after continuous thermal treatments are shown in Figure 4. Figure 4a,b,c displays the Pd particles encapsulated within HTS-1 zeolites having high dispersion and even distribution throughout the zeolite crystals after continuous thermal treatments. The average size of the Pd particle in situ encapsulated within the HTS-1 zeolite is in the range of 1–2 nm. The Pd particle size distribution of the Pd@HTS-1 after continuous thermal treatments is shown in Figure 4d,e,f. The Pd particle sizes slightly increase but remain below 2 nm evenly. The result infers that the Pd particles were encapsulated within the channels of zeolite, and the embedding confinement achieved its high thermal stability. In contrast, Pd particles on Pd/HTS-1 are much larger and more irregular than those encapsulated in Pd@HTS-1 catalysts. Most Pd particles in Pd/HTS-1 only are located on the external surfaces and hence show poor stability through high-temperature treatments. The high-temperature oxidation/reduction/oxidation treatments of the Pd/HTS-1 catalysts resulted in the massive sintering of the Pd species. The size of the Pd particle grew from ∼10 to ∼20 and then to ∼50 nm on average. The results suggest that the confining environment is essential for small and uniform metal particles.22 From these results, it can be proved that most Pd particles are encapsulated in the voids or channels of zeolite crystals with high thermal stability.

Figure 4.

HRTEM images and metal particle size distributions of the Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts before and after high-temperature oxidation–reduction–oxidation treatments. (a, d) Pd@HTS-1-O. (b, e) Pd@HTS-1-OR. (c, f) Pd@HTS-1-ORO. (h) Pd/HTS-1-O. (i) Pd/HTS-1-OR. (j) Pd/HTS-1-ORO.

Besides HRTEM, the dispersion and particle size of monometallic Pd over Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts after reduction in H2 at 400 °C were also investigated by CO adsorption. As shown in Table 2, the Pd dispersion of Pd/HTS-1 and Pd@HTS-1 was 19 and 78%, respectively. The dispersion for Pd@HTS-1 is much higher than Pd/HTS-1, which indicates that the total adsorbing sites in Pd@HTS-1 were more abundant. The average Pd particle size for Pd/HTS-1 estimated from CO adsorption measurements was 5.07 nm, which was smaller than that calculated from the TEM analysis. This is likely due to the existence of tiny Pd nanoparticles, which is almost invisible through HRTEM.36

Table 2. Pd Dispersion and Average Pd Nanoparticle Size Measured by CO-TPD for Pd-Modified TS-1 Catalysts after Reduction in H2 at 400 °C.

Palladium dispersion estimated from CO chemisorption.

Pd nanoparticle diameter estimated from the metal dispersion obtained from CO chemisorption.

Surface-area-weighted mean cluster diameter (dTEM) estimated from TEM analysis, dTEM= Σnidi3 / Σnidi2.

2.2. Shape-Catalytic Test

The encapsulation rate of Pd particles was estimated through comparing the shape-catalytic for reactions of small and large reactants, i.e., aryl nitro-compounds,18 it could be reflected via the restricted access to encapsulated particles by the zeolite aperture size. Therefore, hydrogenation of a mixture of nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene (with minimal kinetic cross-sectional diameters being 0.596 and 0.755 nm, respectively)37 was investigated because only nitrobenzene can diffuse to active sites encapsulated within MFI zeolite channels by way of interconnected gaps and apertures.38

Figure 5 shows the hydrogenation activities of nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene over two different Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts. The results show both the nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene are hydrogenated into their corresponding anilines over Pd-modified HTS-1. Meanwhile, the selectivity of the both catalysts in the nitrobenzene is 100% aniline. The Pd/HTS-1 releases similar reaction rates of nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene hydrogenation. The existence of PdO has a few activities in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene. For the size-dependent catalytic, reaction activities strongly depend on the type of reaction sites. The smaller size with higher edge sites shows higher low-coordinated Pd atoms.39 These low-coordinated Pd atoms usually show higher catalytic activity. That is the reason for Pd@HTS-1 superior activity than Pd/HTS-1 for nitrobenzene reduction. Nitrobenzene can enter into 10-MR windows of TS-1 with an MFI structure (5.1× 5.5 Å and 5.6 × 5.3 Å)40 and contact with intracrystalline active sites of encapsulated particles, while the diffusion of 1-nitronaphthalene with larger size in zeolite interior is difficult. This result further proved the successful encapsulation of Pd into the interior of the MFI zeolite. Different from the encapsulated Pd@HTS-1, when the Pd/HTS-1 is used as a catalyst, the reaction rate of nitrobenzene is much lower, which is due to the larger clusters on the external surface of TS-1. All these results demonstrate that all Pd particles of Pd@HTS-1 reside perfectly within the void structures of TS-1 zeolites and provide the evidence of successful encapsulation.

Figure 5.

Hydrogenation rate of nitrobenzene and 1-nitronaphthalene using four different Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts after reduction treatment.

2.3. In Situ H2O2 Synthesis and Benzyl Alcohol Selective Oxidation

The H2O2 that synthesized from H2 and O2 in situ oxidation benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde over Pd-modified HTS-1 was further investigated, the catalytic oxidation reaction results are shown in Table 3. The unmodified HTS-1 showed no activity. The reason is that the hydrogen cannot be dissociated over the HTS-1 without an active metal site. The catalysts only exhibit activity when Pd is introduced. The benzyl alcohol conversion over the Pd@HTS-1 catalyst was 46.4%, much higher than that of Pd/HTS-1 (7.7%). The dispersion of Pd in the samples prepared by encapsulation and impregnation methods was obtained from CO chemisorption, and values are 78 and 19% for Pd@HTS-1 and Pd/HTS, respectively. The conversion of benzyl alcohol is consistent with the metal dispersion in the catalysts. The TOF values of the Pd@HTS-1 and Pd/HTS-1 are 582.4 and 396.8 h–1. The Pd nanoparticle of Pd@HTS-1 located at the channel intersections of the MFI framework, the interface between the inner Pd particle cores and shell TS-1 framework provides a confined site for this oxidation reaction. The confinement effect could effectively tune the guest–host interaction, resulting in lower product desorption temperature. The lower product desorption energy promotes the product formation. Meanwhile, some research studies that show lower apparent activation energy of oxidation reaction catalyzed by a Pt nanoparticle were found for the reaction occurring in the confined space compared to that on the open surface.41 Furthermore, the benzyl alcohol conversion over Pd@HTS-1 is higher than that of commercial Pd/C and Pt/C catalysts. Santonastaso et al. carried out in situ benzyl alcohol selective oxidation at different temperature gradients over Au-Pd/TiO2. The conversion reached 5.9% at 323 K. These works showed the practicability of tandem reactions for H2O2 synthesis and benzyl alcohol oxidation at lower temperature.42 Joshi et al. found that the OOH species or H2O2 can approach the Ti sites and form the Ti–OOH species in the propylene epoxidation.43 At such temperature, Ti sites are active to form Ti–OOH species. The mesoporous HTS-1 can reduce the diffusion limitations of the reactants to the active sites.

Table 3. Product Distribution of Benzyl Alcohol Oxidation over Different Catalysts with Hydrogen and Oxygend.

| selectivity

(%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| catalyst | conversion (%) | toluene | benzaldehyde | benzoic acid | benzaldehyde production (mmol h–1 kgcat–1) | TOF/h–1 |

| HTS-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pd@HTS-1-ORO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pd/HTS-1-OR | 7.7 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 708.4 | 396.8 |

| Pd@HTS-1-OR | 46.4 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 4268.8 | 582.4 |

| Pd/Ca | 6.9 | 0 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 573.8 | |

| Pt/Ca | 12.7 | 2.1 | 72.1 | 25.8 | 842.4 | |

| Pd@HTS-1-ORb | 9.2 | 0 | 94.2 | 5.8 | 797.3 | |

| HTS-1c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Pd/C and Pt/C are commercial catalysts.

Reaction conditions: O2/Ar (1.1 MPa), benzyl alcohol (0.01 g), 8.5 g of solvent (2.9 g of HPLC water, 5.6 g of MeOH), 0.02 g of 0.1 wt % Pd catalyst, 50 °C, 1200 rpm, 30 min.

Reaction conditions: benzyl alcohol (0.01 g), 8.5 g of solvent (5.6 g of MeOH, 2.22 g of H2O, and 0.68 g of 30 wt % H2O2), 0.02 g of 0.1 wt % Pd catalyst, 50 °C, 1200 rpm, 30 min.

Reaction conditions: H2/Ar (2.9 MPa) and O2/Ar (1.1 MPa), benzyl alcohol (0.01 g), 8.5 g of solvent (2.9 g of HPLC water, 5.6 g of MeOH), 0.02 g of 0.1 wt % Pd catalyst, 50 °C, 1200 rpm, 30 min.

The selectivities of benzaldehyde over the two-series Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts are both 100%, while the selectivities of commercial Pd/C and Pt/C catalysts are much lower, and the by-products include toluene and benzoic acid. Active Pd or Pt sites on the open surfaces of Pd/C or Pt/C possessed a larger particle size, which increased the probability of collision for the reactants. First, the lower product desorption energy of the confinement environment mentioned above promote the benzaldehyde desorption and avoid the deeper oxidation. Meanwhile, the chemisorbed oxygen at the active metal sites dissociated to form atomic oxygen, which is easier to excessive oxidation of benzyl alcohol. In the presence of TS-1, there were a lot of Ti-OOH species. These hydroperoxyl intermediates had weaker oxidability compared with atomic oxygen avoiding the deep oxidation of benzyl alcohol.44 Thus, the Pd@HTS-1 had an excellent selectivity. In terms of selectivity, the Pd@HTS-1 exhibited similar results with the Au(or Pd)/HTS-1 in reference with impregnation in Moreno et al. report.45 They found Ti sites located in the zeolites could form many Ti-OOH species and the hierarchical pore could improve the selectivity of benzaldehyde. This could be advantageous to the stability of Ti-OOH species,46−48 promoting benzyl alcohol turns into benzaldehyde. Thus, we believe that the cooperation of titanium silicalite and mesoporous structure increases the selectivity of this reaction.

To understand the mechanism of the coupling process of in situ H2O2 synthesis and benzyl alcohol selective oxidation. Meanwhile, to research the performance of the catalysts to improve benzaldehyde production when in situ generated hydroperoxy (−OOH) intermediates is used as an oxidizer, the direct H2O2 syntheses over Pd/HTS-1 and Pd@HTS-1 were performed. In our previous work,23 we reported that high-temperature thermal treated hierarchical TS-1 showed a high selectivity in the hydrogen peroxide synthesis. Furthermore, the H2O2 production rate over Pd@TS-1 was significantly improved with the introduction of mesoporous structure. The results of hydrogen peroxide synthesis and degradation over monometallic Pd catalysts in a water–methanol solvent mixture are shown in Table 4. The H2O2 synthesis and degradation rate over Pd@HTS-1-OR were higher than that over Pd@HTS-1-O, while the H2O2 selectivity of Pd@HTS-1-OR was lower than that of Pd@HTS-1-O, which owing to the transform of Pd2+ to Pd0 after reduction, in agreement with former researches.49 As the effect of Pd oxidation state was ascertained, after Pd@HTS-1-OR through 6 h of reoxidation treatment, Pd@HTS-1-ORO showed the highest hydrogen peroxide synthesis activity (35,705 mmol gPd–1 h–1) and a selectivity (47.69%). This phenomenon might be due to the induction of Pd particles surface oxidation. The enrichment of PdO layer on the surface of monometallic Pd catalysts could enhance the performance of hydrogen peroxide synthesis. Metal Pd subnanoparticles on the synthesized Pd@HTS-1-ORO could be dual encapsulated by HTS-1 and the surface PdO layer. But the oxidation of benzyl alcohol cannot be activated by the PdO layer on the surface of monometallic Pd catalysts.50 This led there is no product detected in the benzyl alcohol oxidation over the Pd@HTS-1-ORO.

Table 4. Direct H2O2 Synthesis and Degradation Testing over Different Catalysts.

| catalyst | H2O2 productiona (mmol gPd–1 h–1) | H2O2 degradationb (mmol kgcat–1 h–1) | H2O2 selectivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/HTS-1 | |||

| 500 °C, 4 h, air | 5310 | 44,780 | 34.65 |

| +reduced 400 °C, 2 h | 7460 | 70,530 | 18.91 |

| +500 °C, 6 h, air | 2330 | 49,850 | 21.53 |

| Pd@HTS-1 | |||

| 500 °C, 4 h, air | 23,666 | 27,980 | 42.45 |

| +reduced 400 °C, 2 h | 32,370 | 29,880 | 29.78 |

| +500 °C, 6 h, air | 35,705 | 26,650 | 47.69 |

Reaction conditions: H2/Ar (2.9 MPa) and O2/Ar (1.1 MPa), 8.5 g of solvent (2.9 g of HPLC water, 5.6 g of MeOH), 0.02 g of 0.1 wt % Pd catalyst, RT, 1200 rpm, 30 min.

Reaction conditions: H2/Ar (2.9Mpa), 8.5 g of solvent (5.6 g of MeOH, 2.22 g of H2O, and 0.68 g of 30 wt % H2O2), 0.02 g of 0.1 wt % Pd catalyst, RT, 1200 rpm, 30 min.

In addition, the activity and selectivity of H2O2 over Pd/HTS-1 catalysts were much lower than that on Pd@HTS-1, which could be mainly ascribed to the increase of the particle size in oxidation–reduction–oxidation treatment. It is worth noticing that the Pd/HTS-1-ORO with an average size over 50 nm showed the lowest activity and poor selectivity. Because large nanoparticles (>2.5 nm) with abundant Pd (111) facets were not favorable for the formation of H2O2,51 and the effect of Pd particles surface oxidation was failed to induce.

Figure 6 shows the trend of hydrogen peroxide production with time over the six different Pd-modified TS-1 catalysts. The TON almost is going up with the increase of the reaction time. Meanwhile, the slop of all curves (dTON / dt) decreases with time. The H2O2 net productivity cuts down mildly with time. The decrease of H2O2 cumulative productivity may be due to the rapid decline of H2 partial pressure and the continuous degradation of H2O2. The reaction rate is dependent of both the catalyst and concentration of the reactants.

Figure 6.

TON of H2O2 production over Pd/HTS-1 and Pd@HTS-1 catalysts after oxidation/reduction/reoxidation treatments. TON (turnover number) = mol (H2O2)/mol (surface Pd).

Wilson and Flaherty11 described a number of elementary steps during H2O2 synthesis using Pd catalysts. The hydrogen adsorbed on the Pd particles could dissociate to form H*. Meantime, oxygen adsorption occurred on the Pd sites, subsequently producing OOH** via the proton–electron transfer. The combination of H* and OOH** could ultimately generate H2O2. Nakamura et al.52 found the surface of nanocrystalline TiO2 with peroxo species by UV irradiation, Ti(O2). Ti sites contribute to the adsorption of oxygen.

We also found that there is a small amount of benzoicacid with pure oxygen over the Pd@HTS-1-OR. There is no reaction with the oxidant H2O2 over the HTS-1. Based on the above results, we suggest that this reaction follows a plausible mechanism and is shown in Figure 7. H2 adsorbed on the Pd sites and dissociated to form H*, O2 adsorbed on the Pd sites and dissociated giving O*, while more O2 adsorbed on the Ti sites and formed association OO**, the adsorbed intermediate H* and OO** formed H2O2. The H2O2 subsequently spillovers to the nearby Ti4+ sites and generates Ti-OOH active species. The benzyl alcohol is adsorbed and activated on the Pd sites, which subsequently is selectively oxidized to benzaldehyde by Ti-OOH.

Figure 7.

Illustration of in situ hydrogen peroxide for benzyl alcohol oxidation over Pd@HTS-1.

3. Conclusions

In summary, Pd nanoparticles were successfully encapsulated within HTS-1 voids. Compared to the Pd/HTS-1, Pd nanoparticles of the Pd@HTS-1 show high dispersion and even distribution. In the direct H2O2 synthesis with H2 and O2, we found the Pd@HTS-1 having higher activity and selectivity compared with the Pd/HTS-1. The confinement effect enhances stability against sintering and improves the Pd nanoparticle dispersion. Similarly, the Pd@HTS-1 had a unique performance for benzyl alcohol oxidation and the conversion of benzyl alcohol reaches 46.4% at 323 K with the selectivity of 100% for benzaldehyde. We proposed a reaction mechanism of benzyl alcohol oxidation involving the hydrogen peroxide directly produced via in situ synthesis from hydrogen and oxygen over Pd@HTS-1: the dioxygen was stabilized on the Ti in the framework by forming Ti-OOH species, and the stabilized Ti-OOH selectively oxidized benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde, avoiding the deeper oxidation.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Syntheses of TS-1, HTS-1, Pd/HTS-1, and Pd@HTS-1 Zeolites

The TS-1 and HTS-1 were prepared by a solvent evaporation-assisted dry gel conversion method. The molar ratios of the two solutions are SiO2: 0.04TiO2: 0.2TPAOH: 15EtOH and SiO2: 0.04TiO2: 0.2TPAOH: 0.05HTS: 15EtOH, respectively. The solutions were aged and crystallized. Calcining the collected solids at 500 °C can obtain the TS-1 and HTS-1 catalysts. The Pd/HTS-1 catalyst was prepared through incipient wetness impregnation. The Pd@HTS-1 was prepared by a mercaptosilane-assisted dry gel conversion method. Its solution composition is SiO2/0.04TiO2/0.2TPAOH/15EtOH/xPd/6xKH590 (where x represents the molar amount of Pd). The synthesis and characterization details are given in the Supporting Information.

4.2. Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis and Hydrogenation

The performance of the direct H2O2 synthesis was evaluated in a high-pressure reactor with reactants as follows: H2/Ar (2.9 MPa) and O2/Ar (1.1 MPa),53 8.5 g of solvent (2.9 g of HPLC water, 5.6 g of MeOH),53,54 and 0.02 g of catalyst. H2O2 hydrogenation experiments were evaluated in the solvent (5.6 g of MeOH, 2.22 g of H2O, and 0.68 g of 30 wt % H2O2) with H2/Ar (2.9 MPa). The H2O2 concentration was calibrated before and after reaction.

4.3. Benzyl Alcohol Selective Oxidation Using In Situ Generated H2O2

Benzyl alcohol selective oxidation reaction was evaluated in high-pressure reactor with reactants as follows: 0.02 g of catalyst and benzyl alcohol (0.01 g, 0.092 mmol) were added to a mixed solution (5.6 g of MeOH and 2.9 g of H2O) with 5% H2/Ar (2.9 MPa) and 25% O2/Ar (1.1 MPa). The product analysis was conducted using a gas chromatography Fuli GC9590 and mass spectrometer (GC–MS) Agilent 6890-5973.

Details regarding the experiments, size-selective hydrogenation test process, and catalyst characterization methods can be found in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

The authors were grateful for financial support from the National Science foundation of China (no. 21506189) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (no. LY17B060008). Y.H. acknowledges the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02065.

NH3-TPD profiles, FT-IR spectra of pyridine adsorption, SEM images, and XPS spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ J.L. and L.N. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Taramasso M.; Perego G.; Notari B.. Preparation of porous crystalline synthetic material comprised of silicon and titanium oxides. U.S. Patent 4,410,501, Oct 18, 1983.

- Sancheti S. V.; Yadav G. D.; Ghosh P. K. Synthesis and application of novel NiMoK/TS-1 for selective conversion of fatty acid methyl esters/triglycerides to olefins. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5061–5071. 10.1021/acsomega.9b03993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A. From microporous to mesoporous molecular sieve materials and their use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2373–2420. 10.1021/cr960406n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y.; Marinkovic S.; Estrine B.; Qiang W.; Enderlin G. Oxidation of furfural and furan derivatives to maleic acid in the presence of a simple catalyst system based on acetic acid and TS-1 and hydrogen peroxide. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2561–2568. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriminna R.; Albanese L.; Meneguzzo F.; Pagliaro M. Hydrogen peroxide: a key chemical for today’s sustainable development. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 3374–3381. 10.1002/cssc.201600895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Serna J.; Moreno T.; Biasi P.; Cocero M. J.; Mikkola J.-P.; Salmi T. O. Engineering in direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide: targets, reactors and guidelines for operational conditions. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2320–2343. 10.1039/c3gc41600c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel H.; Weber W.. Manufacture of hydrogen peroxid. U.S. Patent 1,108,752, Aug 15, 1914.

- Choudhary V. R.; Samanta C.; Choudhary T. V. Direct oxidation of H2 to H2O2 over Pd-based catalysts: influence of oxidation state, support and metal additives. Appl. Catal., A 2006, 308, 128–133. 10.1016/j.apcata.2006.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta C.; Choudhary V. R. Direct synthesis of H2O2 from H2 and O2 and decomposition/hydrogenation of H2O2 in an aqueous acidic medium over halide-modified Pd/Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal., A 2007, 330, 23–32. 10.1016/j.apcata.2007.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freakley S. J.; He Q.; Harrhy J. H.; Lu L.; Crole D. A.; Morgan D. J.; Ntainjua E. N.; Edwards J. K.; Carley A. F.; Borisevich A. Y.; Kiely C. J.; Hutchings G. J. Palladium-tin catalysts for the direct synthesis of H2O2 with high selectivity. Science 2016, 351, 965–968. 10.1126/science.aad5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. M.; Flaherty D. W. Mechanism for the direct synthesis of H2O2 on Pd clusters: heterolytic reaction pathways at the liquid-solid interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 574–586. 10.1021/jacs.5b10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Lunsford J. H. Controlling factors in the direct formation of H2O2 from H2 and O2 over a Pd/SiO2 catalyst in ethanol. Appl. Catal., A 2006, 314, 94–100. 10.1016/j.apcata.2006.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Shao Q.; Hu M.; Chen Y.; Huang X. Hollow Pd-Sn nanocrystals for efficient direct H2O2 synthesis: The critical role of Sn on structure evolution and catalytic performance. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3418–3423. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto A.; Palomino M.; Díaz U.; Corma A. One-pot two-step process for direct propylene oxide production catalyzed by bi-functional Pd(Au)@TS-1 materials. Appl. Catal., A 2016, 523, 73–84. 10.1016/j.apcata.2016.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T.; Tanaka K.; Haruta M. Selective vapor-phase epoxidation of propylene over Au/TiO2 catalysts in the presence of oxygen and hydrogen. J. Catal. 1998, 178, 566–575. 10.1006/jcat.1998.2157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-S.; Lai L.-C.; Akatay M. C.; Stach E. A.; Ribeiro F. H.; Delgass W. N. Probing the gold active sites in Au/TS-1 for gas-phase epoxidation of propylene in the presence of hydrogen and oxygen. J. Catal. 2012, 296, 31–42. 10.1016/j.jcat.2012.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gage S. H.; Engelhardt J.; Menart M. J.; Ngo C.; Leong G. J.; Ji Y.; Trewyn B. G.; Pylypenko S.; Richards R. M. Palladium intercalated into the walls of mesoporous silica as robust and regenerable catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation of phenolic compounds. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 7681–7691. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Liu Q.; Zhang Y.; Su X.; Huang Y.; Zhang T. In situ synthesis of metal clusters encapsulated within small-pore zeolites via a dry gel conversion method. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11320–11327. 10.1039/C8NR00549D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M.; Wu Z.; Iglesia E. Mercaptosilane-assisted synthesis of metal clusters within zeolites and catalytic consequences of encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9129–9137. 10.1021/ja102778e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Chen L.; Ren N.; Zhang Y.; Tang Y. Zeolitic microcapsule with encapsulated platinum nanoparticles for one-pot tandem reaction of alcohol to hydrazone. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8583–8585. 10.1039/c2cc33701k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Boucheron T.; Tuel A.; Farrusseng D.; Meunier F. Size-selective hydrogenation at the subnanometer scale over platinum nanoparticles encapsulated in silicalite-1 single crystal hollow shells. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1824–1826. 10.1039/c3cc48648f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S.; Zones S. I.; Iglesia E. Encapsulation of metal clusters within MFI via interzeolite transformations and direct hydrothermal syntheses and catalytic consequences of their confinement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15280–15290. 10.1021/ja507956m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J.; Wei J.; Niu L.; Lu C.; Hu Y.; Xiang Y.; Zhang G.; Zhang Q.; Ding C.; Li X. Highly efficient hydrogen peroxide direct synthesis over a hierarchical TS-1 encapsulated subnano Pd/PdO hybrid. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13398–13402. 10.1039/C9RA02452B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Lin M.; Peng X.; Zhu B.; Shu X. Hierarchical TS-1 synthesized effectively by post-modification with TPAOH and ammonium hydroxide. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 44963–44971. 10.1039/C6RA06657G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.; Xiao J.; Zhang L.; Wang W.; Hong Y.; Huang H.; Jiang Y.; Li L.; Wang C. Copper-modified TS-1 catalyzed hydroxylation of phenol with hydrogen peroxide as the oxidant. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 101071–101078. 10.1039/C6RA20980G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song W.; Zuo Y.; Xiong G.; Zhang X.; Jin F.; Liu L.; Wang X. Transformation of SiO2 in titanium silicalite-1/SiO2 extrudates during tetrapropylammonium hydroxide treatment and improvement of catalytic properties for propylene epoxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 253, 464–471. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q.; Dou B. J.; Tian H.; Li J. J.; Li P.; Hao Z. P. Mesoporous silicalite-1 nanospheres and their properties of adsorption and hydrophobicity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 129, 30–36. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.08.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D.; Liu J.; Wang Z.-M.; Kumagai A.; Endo T.; Yin H.-Q.; Wei F.-S. Cellulose-nanofiber-mediated sorption-benefitting holed silicalite-1 crystals. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12995–13004. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian P.; Ouyang L.; Xu X.; Ao C.; Xu X.; Si R.; Shen X.; Lin M.; Xu J.; Han Y.-F. The origin of palladium particle size effects in the direct synthesis of H2O2: Is smaller better?. J. Catal. 2017, 349, 30–40. 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.; Li D.; Yang X.; Yu Y.; Wu S.; Han Y.; Yang Q.; Jiang D.; Xiao F.-S. Synthesis, characterization, and catalytic activity of mesostructured titanosilicates assembled from polymer surfactants with preformed titanosilicate precursors in strongly acidic media. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 8972–8980. 10.1021/jp027405l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.; Lyu J.; Cen J.; Zhang Q.; Wang Q.; Han W.; Rui J.; Li X. Promoting effects of MgO and Pd modification on the catalytic performance of hierarchical porous ZSM-5 for catalyzing benzene alkylation with methanol. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 63044–63049. 10.1039/C5RA12589H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivallan M.; Seguin E.; Thomas S.; Lepage M.; Takagi N.; Hirata H.; Thibault-Starzyk F. Platinum sintering on H-ZSM-5 followed by chemometrics of CO adsorption and 2D pressure-jump IR spectroscopy of adsorbed species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 785–789. 10.1002/anie.200905181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippaerts A.; Paulussen S.; Breesch A.; Turner S.; Lebedev O. I.; Van Tendeloo G.; Sels B.; Jacobs P. Unprecedented shape selectivity in hydrogenation of triacylglycerol molecules with Pt/ZSM-5 zeolite. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 123, 4033–4035. 10.1002/ange.201007513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Kim W.; Seo Y.; Kim J.-C.; Ryoo R. n-Heptane hydroisomerization over Pt/MFI zeolite nanosheets: effects of zeolite crystal thickness and platinum location. J. Catal. 2013, 301, 187–197. 10.1016/j.jcat.2013.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Li S.; Wang Y.; Herron J. A.; Xu Y.; Allard L. F.; Lee S.; Huang J.; Mavrikakis M.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos M. Catalytically active Au-O(OH)x-species stabilized by alkali ions on zeolites and mesoporous oxides. Science 2014, 346, 1498–1501. 10.1126/science.1260526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Han W.; Lyu J.; Zhang Q.; Guo L.; Li X. In situ encapsulation of platinum clusters within H-ZSM-5 zeolite for highly stable benzene methylation catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 6140–6150. 10.1039/C7CY01270E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J.; Zhang Z.; Hu P.; Ding L.; Xue N.; Peng L.; Guo X.; Lin M.; Ding W. Platinum nanoparticles encapsulated in MFI zeolite crystals by a two-step dry gel conversion method as a highly selective hydrogenation catalyst. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6893–6901. 10.1021/acscatal.5b01823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. K.; Parker S. F.; Pritchard J.; Piccinini M.; Freakley S. J.; He Q.; Carley A. F.; Kiely C. J.; Hutchings G. J. Effect of acid pre-treatment on AuPd/SiO2 catalysts for the direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 812–818. 10.1039/C2CY20767B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J.; Wang J.; Lu C.; Ma L.; Zhang Q.; He X.; Li X. Size-dependent halogenated nitrobenzene hydrogenation selectivity of Pd nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 2594–2601. 10.1021/jp411442f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotailo G. T.; Lawton S. L.; Olson D. H.; Meier W. M. Structure of synthetic zeolite ZSM-5. Nature 1978, 272, 437–438. 10.1038/272437a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q.; Bao X. Surface chemistry and catalysis confined under two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1842–1874. 10.1039/C6CS00424E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santonastaso M.; Freakley S. J.; Miedziak P. J.; Brett G. L.; Edwards J. K.; Hutchings G. J. Oxidation of benzyl alcohol using in situ generated hydrogen peroxide. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 1455–1460. 10.1021/op500195e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. M.; Delgass W. N.; Thomson K. T. Comparison of the catalytic activity of Au3, Au4+, Au5, and Au5– in the gas-phase reaction of H2 and O2 to form hydrogen peroxide: a density functional theory investigation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 22392–22406. 10.1021/jp052653d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boronat M.; Pulido A.; Concepción P.; Corma A. Propene epoxidation with O2 or H2-O2 mixtures over silver catalysts: theoretical insights into the role of the particle size. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 26600–26612. 10.1039/C4CP02198C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno I.; Dummer N. F.; Edwards J. K.; Alhumaimess M.; Sankar M.; Sanz R.; Pizarro P.; Serrano D. P.; Hutchings G. J. Selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol using in situ generated H2O2 over hierarchical Au-Pd titanium silicalite catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 2425–2434. 10.1039/c3cy00493g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q.; Sun K.; Feng Z.; Li G.; Guo M.; Fan F.; Li C. A thorough investigation of the active titanium species in TS-1 zeolite by in situ UV resonance raman spectroscopy. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012, 18, 13854–13860. 10.1002/chem.201201319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordiga S.; Bonino F.; Damin A.; Lamberti C. Reactivity of Ti(IV) species hosted in TS-1 towards H2O2–H2O solutions investigated by ab initio cluster and periodic approaches combined with experimental XANES and EXAFS data: a review and new highlights. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 4854–4878. 10.1039/b706637f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W.; Frei H. Photochemical and FT-IR probing of the active site of hydrogen peroxide in Ti silicalite sieve. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9292–9298. 10.1021/ja012477w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melada S.; Rioda R.; Menegazzo F.; Pinna F.; Strukul G. Direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide on zirconia-supported catalysts under mild conditions. J. Catal. 2006, 239, 422–430. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Cao Y.; Zhao L.; Wang Y.; He Z.; Xing W.; Bai P.; Mintova S.; Yan Z. Formation of PdO on Au–Pd bimetallic catalysts and the effect on benzyl alcohol oxidation. J. Catal. 2019, 375, 32–43. 10.1016/j.jcat.2019.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Hoffman A.; Yates J. T. Jr. Adsorption kinetics and isotopic equilibration of oxygen adsorbed on the Pd(111) surface. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 5787–5792. 10.1063/1.456386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R.; Imanishi A.; Murakoshi K.; Nakato Y. In situ FTIR studies of primary intermediates of photocatalytic reactions on nanocrystalline TiO2 films in contact with aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7443–7450. 10.1021/ja029503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta C. Direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from hydrogen and oxygen: an overview of recent developments in the process. Appl. Catal., A 2008, 350, 133–149. 10.1016/j.apcata.2008.07.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. K.; Thomas A.; Solsona B. E.; Landon P.; Carley A. F.; Hutchings G. J. Comparison of supports for the direct synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from H2 and O2 using Au–Pd catalysts. Catal. Today 2007, 122, 397–402. 10.1016/j.cattod.2007.01.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.