Abstract

Background.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is the most common manifestation of malignancy in the oral cavity. Adjuncts are available for clinicians to evaluate lesions that seem potentially malignant. In this systematic review, the authors summarized the available evidence on patient-important outcomes, diagnostic test accuracy (DTA), and patients, values and preferences (PVPs) when using adjuncts for the evaluation of clinically evident lesions in the oral cavity.

Types of Studies Reviewed.

The authors searched for preexisting systematic reviews and assessed their quality using the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews tool. The authors updated the selected reviews and searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify randomized controlled trials and DTA and PVPs studies. Pairs of reviewers independently conducted study selection, data extraction, and assessment of the certainty in the evidence by using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach.

Results.

The authors identified 4 existing reviews. DTA reviews included 37 studies. The authors retrieved 7,534 records, of which 9 DTA and 10 PVPs studies were eligible. Pooled sensitivity and specificity of adjuncts ranged from 0.39 to 0.96 for the evaluation of innocuous lesions and from 0.31 to 0.95 for the evaluation of suspicious lesions. Cytologic testing used in suspicious lesions appears to have the highest accuracy among adjuncts (sensitivity, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.86 to 0.98; specificity, 0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.88 to 0.99; low-quality evidence).

Conclusions and Practical Implications.

Cytologic testing appears to be the most accurate adjunct among those included in this review. The main concerns are the high rate of false-positive results and serious issues of risk of bias and indirectness of the evidence. Clinicians should remain skeptical about the potential benefit of any adjunct in clinical practice.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, potentially malignant disorders, diagnostic test accuracy, patients’ values and preferences

In 2017, an estimated 49,670 new cases of cancer in the oral cavity and pharynx will be diagnosed in the United States, with 9,700 disease-associated deaths.1 Estimates for cancer in the oral cavity alone include 32,670 new cases and 6,650 deaths.1 Most of these cancers will be squamous cell carcinomas. Survival is highly stage dependent, with 83.7% of people surviving 5 years after diagnosis of localized cancer and 64.2% and 38.5% of people surviving with regional and distant metastases.2

Approximately 70% of all new cases are diagnosed at a late stage, underscoring the importance of proper patient evaluation for the prevention or early detection of disease.1 Clinicians detect and assess oral potentially malignant disorders (PMDs) and oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs) by using the combination of an intra- and extraoral conventional visual and tactile examination and the detection of dysplasia through tissue biopsy. However, although as many as 10% of patients will have some type of oral mucosal abnormality, only a small fraction of these abnormalities or lesions will be biologically and clinically significant.3

Conventional visual and tactile examination in the oral cavity is limited in its ability to help discriminate between similar-appearing lesions or disorders that may require considerably different treatments. To address analogous challenges at other anatomic sites, clinicians have used adjunctive tests or devices, simply known as adjuncts, such as mammography, the Papanicolaou smear, and colonoscopy, to assist in the detection and evaluation of disease. A number of adjuncts have become commercially available to aid in the evaluation and discrimination of oral mucosal lesions.4–8 These adjuncts can be divided into 3 broad categories: lesion detection or discrimination, lesion assessment, and risk assessment.

Lesion detection or discrimination. This category is composed mostly of light-based handheld adjuncts proposed to aid clinicians in the detection and margin discrimination of lesions by using the principles of autofluorescence and tissue reflectance. Some also would classify vital staining within this category.

Lesion assessment. This category of adjuncts is intended to assist clinicians in assessing the biological or clinical relevance of a mucosal abnormality through cytomorphologic analysis of disaggregated epithelial cells (cytologic testing). Some also would classify vital staining within this category.

Risk assessment. This category is composed of saliva-based adjuncts that involve using a number of biomarkers, including proteins, RNAs, and DNAs.

The purpose of this systematic review was to address the potential benefits and limitations of commercially available adjuncts to aid in the detection, discrimination, and assessment of oral mucosal lesions, particularly PMDs and OSCC in adult patients. This article is an update and major revision of the 2010 review6 which was performed by an expert panel of clinical and subject matter experts convened by the American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs. The ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry and the Cochrane Collaboration provided methodological support for the development and authorship of this review.

Adjuncts can be incorporated in the diagnostic pathway to triage before an existing test, replace an existing test, or add on to an existing test to increase accuracy.9 For this systematic review, we interpreted data from the included studies in the context of using adjuncts to triage the need for biopsy and not as replacement for biopsy.10 Clinicians typically use triage tools in an early stage of the diagnostic process to identify patients with a particular finding that will be informative for subsequent steps in the testing pathway. These findings informed the development of a 2017 evidence-based clinical practice guideline by the ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry,11 which contains recommendation statements to guide the clinical decision-making process (eTable 1).

METHODS

This report follows the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses12 statement and other methodological recommendations from the Cochrane Screening and Diagnostic Tests Methods Group.13

Selection criteria for the studies in this review.

Type of studies.

We included cross-sectional and cohort diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which the investigators assessed the effectiveness or accuracy of adjuncts. We excluded study designs such as case-control studies, case reports, case series, abstracts, and uncontrolled reports.

Type of participants and target conditions.

Studies eligible for inclusion involved adult patients (aged 18 years or older), ideally in the context of primary care settings, seeking care with or without clinically evident lesions in the oral cavity, encompassing the labial mucosae, buccal mucosae, gingival or alveolar ridge mucosae, tongue, floor of mouth, hard and soft palate, and retromolar trigone. If clinically evident, lesions could manifest as seemingly innocuous or nonsuspicious, suspicious, or seemingly malignant. We excluded studies involving patients seeking care for cancers of the lips, oropharynx, and salivary glands.

Index tests and the criterion standard.

Definitive diagnosis of PMDs and OSCC requires using a criterion standard wherein the patient undergoes a biopsy of the lesion followed by a histopathologic assessment. Studies not specifying any criterion standard were ineligible for inclusion in this systematic review. Other tests, devices, techniques, or technologies intended to facilitate clinical decision making are index tests. The aforementioned adjuncts act as index tests in the context of this review and are used as triage tools in practice. Adjuncts can have either a positive (with suspicion of target condition) or negative (without suspicion of target condition) test result.

We defined several adjuncts of interest a priori and assessed them regarding their DTA and effectiveness when evaluating patients with

no clinically evident lesions in the oral cavity;

clinically evident seemingly innocuous or nonsuspicious lesions in the oral cavity;

clinically evident suspicious lesions or seemingly malignant lesions in the oral cavity.

Adjuncts include the following:

cytologic testing (for example, OralCDx [OralScan Laboratories, Inc.], OralCyte [ClearCyte Diagnostics Inc.], ClearPrep OC [Resolution Biomedical]);

autofluorescence (for example, VELscope [LED Dental], OralID [Forward Science]); tissue reflectance (for example, ViziLite Plus [DenMat Holdings, LLC], Microlux DL [AdDent Inc.]);

vital staining (for example, toluidine blue);

salivary adjuncts (for example, OraRisk [Oral DNA Labs], SaliMark [PeriRx LLC], OraMark [OncAlert Labs], MOP genetic oral cancer screening [PCG Molecular], OraGenomics);

additional adjuncts of interest (for example, Identafi [StarDental]).

We also included combinations of aforementioned adjuncts if 1 adjunct informed the use of the second adjunct. We reported results separately if the investigators used 2 index tests in a study independently of each other. We excluded adjuncts not commercially available in the United States at the date of the search.

Types of outcomes and estimates.

Patient-important outcomes are defined as “outcomes for which—even if it were the only outcome improved by the intervention— the patient would still consider receiving the intervention in face of some adverse events, costs, and burden.”14–16 In the context of adjuncts, patients will prioritize outcomes such as morbidity and mortality and serious adverse events over other surrogate outcomes such as DTA estimates. We defined the following patient-important outcomes a priori and included all-cause mortality, OSCC mortality, survival, quality of life, unnecessary biopsy, costs, incidence of OSCC, and anxiety and stress. DTA estimates defined a priori included sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios. We used the proportion of true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative results to calculate DTA estimates. We excluded studies when reporting made it impossible to create a contingency table.

Positivity thresholds.

As stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Reviews, “binary test outcomes are defined on the basis of a threshold for test positivity and change if the threshold is altered.”13 Whenever possible, we considered all levels of oral epithelial dysplasia (mild, moderate, and severe) assessed during biopsy or histopathologic assessment as positive for the target condition and absence of dysplasia assessed during biopsy or histopathologic assessment as negative for the target condition. For cytologic testing adjuncts, we grouped any atypical results with dysplastic results when possible and considered them positive for the target condition.

Using preexisting evidence.

As a way to optimize the development of systematic reviews to inform ADA guidelines, we established a collaboration with the Cochrane Oral Health Group. The purpose of this collaboration was to increase efficiency in the use of secondary evidence for the development of clinical practice guidelines by using preexisting high-quality systematic reviews. In the event that no Cochrane reviews were available, we searched for non-Cochrane systematic reviews.

The eligible reviews had to meet 3 criteria. The first was being assessed as having moderate to high methodological quality. The second was being as current as possible. The third was meeting the selection criteria in relation to the type of study design, patient characteristics, index tests, criterion standard, and outcomes.

Identifying relevant systematic reviews.

We identified eligible systematic reviews through our collaboration with the Cochrane Oral Health Group. Members of the group suggested Cochrane reviews that potentially met our selection criteria. When no Cochrane reviews were available for a specific clinical question, we searched for non-Cochrane reviews by using the PubMed Clinical Queries tool and prioritized the most current ones (from 2010 to the present). To determine final eligibility, we used the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews tool to assess their methodological quality.17

Literature search to update existing reviews and linked evidence on patient-important outcomes.

With the purpose of updating potentially eligible existing reviews, we searched MEDLINE via Ovid, Embase via Ovid, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We included all study designs in the initial search. We also added economic analysis and patients, values and preferences (PVPs). After reviewing the results, we deemed it necessary to rerun the related Cochrane searches. We rebuilt the Cochrane searches for Embase, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We then restricted that language to RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses as a means of ensuring the update of the Cochrane review and to inform the patient-important outcomes (linked evidence) of interest. Given that literature related to salivary adjuncts was limited within the bounds of the existing searches, we removed study design considerations to open up the possibilities of finding relevant language. We restricted the updated Cochrane searches from April 2013 (latest update by Cochrane) to December 2016. We ran the search on economic analysis and PVPs from inception to November 2016. The amended search for salivary adjuncts was run from April 2013 (latest update by Cochrane) to February 2017 (Appendix 1, available online at the end of this article). We did not apply restrictions on language or publication status.

Selection of primary studies for update of systematic reviews and data extraction.

We conducted the study selection process in 3 phases. In the first phase, 2 reviewers (M.P.T., O.U.) independently reassessed eligibility of all included studies in the 20154 and 20135 Cochrane reviews. In the second phase, the same 2 reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of retrieved references from the updated search strategy for both DTA studies and RCTs. In the third phase, reviewers independently screened the full text of all potentially eligible studies. We resolved any disagreements at full-text level via discussion and consensus. When consensus was elusive, a third reviewer (A.C.L.) arbitrated and decided final eligibility. For information about the data extraction process, see Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article).

Summary measures of DTA and patient-important outcomes at a study level.

DTA studies included in this review reported results in contingency tables as a cross-classification of target condition status (condition present or absent determined by using the criterion standard) and the adjunct,s outcome (condition positive or negative determined by means of the index test).13 We presented data as true-positive, false-positive, true-negative, and false-negative results. We then calculated summary measures of DTA such as sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sensitivity and specificity are measures defined as conditional on the disease status, whereas likelihood ratios can be used to update the pretest probability of disease to the posttest probability once the test result is known.18 We planned on obtaining the prevalence of PMDs and OSCC in the US adult population and using sensitivity and specificity to calculate absolute measures. For patient-important outcomes reported dichotomously, we planned to present their results by using relative risks and their 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes, we considered the use of a mean difference, the standard deviation, and the 95% CI as summary measures.

Assessment of the risk of bias of included studies.

Similar to methods used in other Cochrane systematic reviews on DTA, we used a modified version of the QUADAS-2 tool19 to assess the risk of bias and applicability of primary diagnostic accuracy studies included in our review. Two reviewers (M.P.T., O.U.) used the tool independently and in duplicate. We assessed the following domains in each study: patient selection, index test, criterion standard, and flow and timing. We assessed all domains in terms of the risk of bias by using signaling questions to assist in the judgments. We also assessed the first 3 domains in terms of their applicability. Other important considerations for the quality assessment included representativeness of the study sample, extent of verification bias, use of blinded methods for interpreting test results, and presence of missing data.13

Data synthesis and meta-analysis.

We recorded the number of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative, and false-negative results by using software (Review Manager, Version 5.3, Cochrane Collaboration). We recorded all new events at the lesion level to mirror the data presented in the 2015 Cochrane review.4 For each study, we displayed estimates of DTA, sensitivity, and specificity, along with their 95% CIs, in coupled forest plots, as well as plotted in summary receiver operating characteristic curve space according to index test. We performed meta-analysis to obtain pooled estimates for sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios for each adjunct by using the bivariate approach13 (SAS, Version 9.4, SAS Institute). When too few studies were available for pooling by using the bivariate approach, we obtained the pooled estimate by combining their contingency tables for the associated comparison. We acknowledge that this method may have a tendency to create artificially narrower CIs. However, considering that this review is informing a clinical practice guideline, we prioritized the presentation of pooled estimates to facilitate decision making.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence.

We assessed the quality of the evidence for all included outcomes by using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach with specification for the diagnostic test context.20 The GRADE approach provides a framework to assess the degree of confidence we can place in DTA and patient-important outcomes. In GRADE, cross-sectional or cohort studies in patients with diagnostic uncertainty and a comparison with an appropriate criterion standard start as high-quality evidence (high certainty in the evidence). Our certainty is reduced, however, when these studies have serious issues such as risk of bias or limitations in study design, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, or high probability of publication bias (eTable 2).21 Such issues move the quality of the evidence from high to moderate, low, or very low certainty. We presented data in summary-of-findings tables created using software (GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool, McMaster University and Evidence Prime). For a detailed description of the methods used to assess heterogeneity, publication bias, and the planned sensitivity analysis, see Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article).

RESULTS

Results of the search.

We identified 2 Cochrane reviews4,5 in which the investigators reported on DTA for adjuncts in patients both with and without clinically evident lesions developed by the Cochrane Oral Health Group. In addition, we identified 2 non-Cochrane reviews covering the use of salivary adjuncts.22,23

From the 2015 Cochrane review, we identified 37 studies that were eligible.4 From the 2013 Cochrane review, no primary studies met our selection criteria.5 The other 2 non-Cochrane systematic reviews were published in 2016 and 2017 and covered salivary adjuncts for the early diagnosis of OSCC, and no updating process was required.22,23

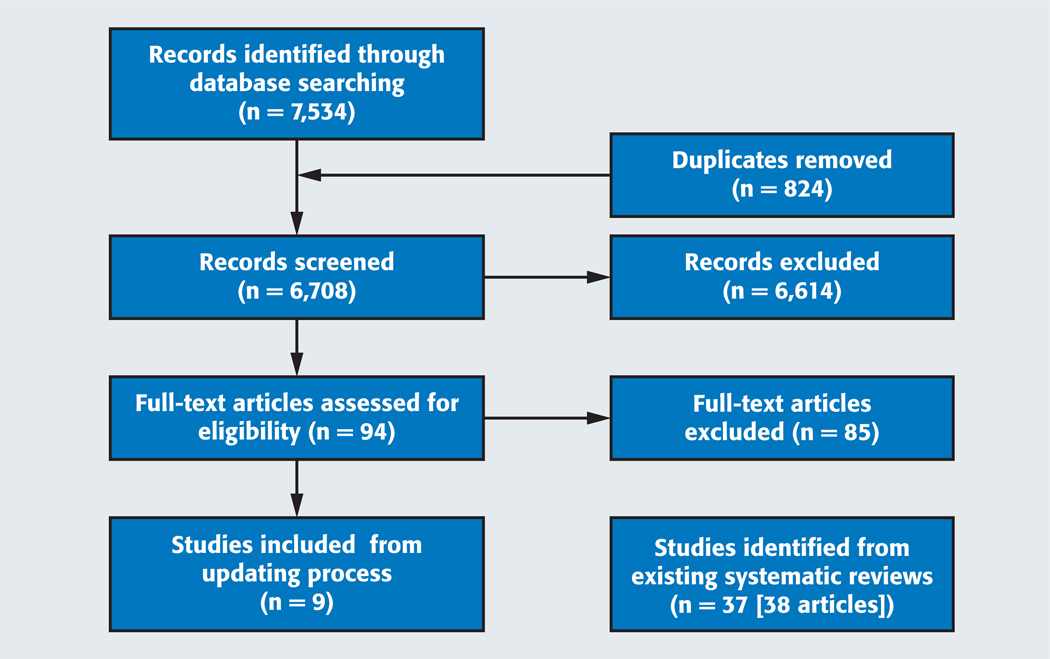

During the updating process of the evidence from these reviews, we identified 7,534 references from the electronic databases. After eliminating duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 6,708 citations. We selected 94 potentially eligible articles that we then screened using full texts. Of the 94 full-text articles, we selected 9 studies as part of the updating process and excluded the remaining 85 (eTable 3,4 available online at the end of this article). This resulted in a total of 46 included studies (47 reports) (Figure 1).4,12 No studies on salivary adjuncts met our selection criteria, so we performed a comprehensive search to identify published systematic reviews.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses12 flow chart of the screening and study selection process.

During the process of identifying studies on PVPs, we identified 2,616 citations and included 59 of those for full-text screening. Finally, 10 studies were eligible. Investigators in none of the studies reported on the relative importance of outcomes in the context of the use of adjuncts for the evaluation of PMDs.

Characteristics of included studies.

DTA studies.

In the 46 included studies, the investigators enrolled a total of 4,543 participants ranging in age from 18 through 80 years, conducted the studies between 1980 and 2016, and reported data on the diagnostic accuracy of the following adjuncts: autofluorescence,24–31 cytologic testing,32–47 vital staining,42,48–61 tissue reflectance,24,62–66 tissue reflectance and vital staining,28,62,65,67,68 and cytologic testing and vital staining.69,70 Investigators had conducted most studies in secondary24,26–28,30–34,36,37,41,44–47,49–51,53,55–62,65,67,68,70 or tertiary25,29,35,39,40,43,48,54,57,63,64 care settings and in the United Kingdom,24,49,66 Italy,30,39,40,48 Germany,26,27,31,34,35,43 Spain,45,50 Taiwan,52 China,53,54 Iran,32 the United States,44,46,55,58,62,67 Australia,25,63,64 Turkey,69 India,28,36,37,42,47,51,56,59,61,65,70 Poland,68 Japan,29 Brazil,33,57 Canada,41 Sri Lanka,38,60 or Pakistan.60 The target condition for all studies encompassed PMDs or OSCC (eTable 4).24–70

Investigators in many of the included primary studies did not disclose any conflicts of interest and sources of funding, though a few provided information regarding links to industry funding and grants for research.33,40,44,46,52,54,60,67,69 We identified no studies in which the investigators assessed patient-important outcomes such as all-cause mortality, OSCC mortality, survival time, quality of life, costs, incidence of OSCC, and anxiety or stress, and none met our selection criteria.

PVPs studies.

One systematic review71 and 9 primary studies72–80 including 1,950 participants provided information about patients, perspective, barriers, and facilitators during the evaluation of PMDs. For a detailed description of the included studies and results, see eTable 571–80 and Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article).

Determination of prevalence of disease.

We were unable to identify data on the prevalence of PMDs and OSCC in the US population in the published literature. We contacted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, and National Cancer Institute to determine whether they had this information. Although these agencies were unable to give us an accurate estimate, we built our prevalence estimate by using the 2013 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data from the National Cancer Institute and 2010 census data for people 45 years or older to calculate and obtain an estimated prevalence of OSCC in the United States of 0.25%.81,82 We recognized that this estimate did not include PMDs, so we used an estimate of 2.0% to illustrate the potential prevalence of PMDs and OSCC in an attempt to account for this limitation in current available data.

Risk of bias of included reviews.

We identified 4 preexisting systematic reviews meeting the selection criteria for the clinical questions included in this review.4,5,22,23 For more information, see eTables 6 through 94,5,16,22,23 and Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article).

Risk of bias of primary studies.

Poor reporting did not allow us to conduct a complete risk of bias assessment for many of the included studies. Across the domains of patient selection, index test, and criterion standard, we determined that approximately 50% of the included studies were unclear. For the flow and timing domains, reporting quality was much higher, and we considered them as the domains of least concern from a risk of bias perspective. There were almost no applicability issues among the studies (eFigure 125–70 and eFigure 2, available online at the end of this article).

DTA of adjuncts.

Because no studies in which the investigators assessed patient-important outcomes met our selection criteria, we used DTA estimates as surrogate outcomes.

Evidence assessing the use of adjuncts to evaluate patients with no clinically evident lesions.

The authors of the 2013 Cochrane review5 found no studies informing the accuracy and effect of adjuncts. In our update of this preexisting review, we also failed to identify studies meeting our selection criteria. The panel thought it was important to include the best available evidence for this patient scenario and thus decided to amend the selection criteria for salivary adjuncts to include case-control studies. Systematic reviews conducted in 2016 and 2017 met this new selection criterion and summarized the available evidence on the potential use of salivary adjuncts for the early diagnosis of OSCC and malignant disorders.22,23 Most of the studies we identified were diagnostic-test case-control studies, followed by a few cross-sectional and prospective studies. The sampling methods to collect saliva varied across studies (unstimulated saliva or oral rinse), and most of them were assessed as being of low or moderate methodological quality.23 Most studies had small sample sizes with fewer than 100 participants, although a few studies were larger.22,23

Most biomarkers showed a wide range of DTA results (sensitivity ranging from 0.5–0.9 and specificity ranging from 0.63–0.90).22 Some biomarkers were clearly shown not to be associated with the presence of early PMDs and did not suggest the ability to inform disease progression.22 In contrast, other biomarkers were elevated significantly in those with OSCC compared with those without OSCC.23

We acknowledge that people with no clinically evident lesions and those with clinically evident lesions deemed seemingly innocuous or nonsuspicious (as opposed to populations with suspicious lesions, which primarily were included in these reviews) are the ones who may benefit the most if these adjuncts show improved DTA in the future.

Evidence assessing the use of adjuncts to evaluate patients with clinically evident, seemingly innocuous (nonsuspicious) lesions or symptoms.

We identified 2 studies28,36 in which the investigators addressed the DTA of autofluorescence, cytologic testing, and tissue reflectance and vital staining in patients with seemingly innocuous or nonsuspicious lesions. Pooled sensitivity and specificity of adjuncts ranged from 0.39 to 0.96 for the evaluation of innocuous lesions. eTable 424–70 summarizes the characteristics of the included populations, and investigators conducted all studies in a secondary or tertiary care setting.

Autofluorescence.

One study informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 156 lesions.28 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard was unclear (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). When a clinician uses autofluorescence, 50% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjuncts (sensitivity, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.79). However, 39% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjuncts (specificity, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.47) (eFigure 3,28 available online at the end of this article). See Table 1,28 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 1:

Autofluorescence adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident, seemingly innocuous, or nonsuspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 125 (53 to 198) | 1,000 (420 to 1,580) | 156 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 125 (52 to 197) | 1,000 (420 to 1,580) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 38,903 (30,923 to 46,883) | 38,220 (30,380 to 46,060) | 156 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 60,847 (52,867 to 68,827) | 59,780 (51,940 to 67,620) | ||

Setting: primary care. Sensitivity, 0.50 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.21 to 0.79). Specificity, 0.39 (95% CI, 0.31 to 0.47). Positive likelihood ratio, 0.82 95% CI, 0.46 to 1.46). Negative likelihood ratio, 1.29; (95% CI, 0.70 to 2.35). Source: Mehrotra and colleagues.28

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

We judged the patient selection and index test domains as being at high risk of bias.

The investigators conducted the study in a secondary care setting. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

The positivity threshold for the reference test was unclear.

Cytologic testing.

One study informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 79 lesions.36 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard was unclear (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). When clinicians use cytologic testing, 96% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.00). However, 90% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.97) (eFigure 4,36 available online at the end of this article). See Table 2,36 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 2:

Cytologic adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident, seemingly innocuous, or nonsuspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 240 (203 to 250) | 1,920 (1,620 to 2,000) | 79 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 10 (0 to 47) | 80 (0 to 380) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 89,775 (78,803 to 96,758) | 88,200 (77,420 to 95,060) | 79 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 9,975 (2,992 to 20,947) | 9,800 (2,940 to 20,580) | ||

Setting: primary care. Sensitivity, 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.81 to 1.00). Specificity, 0.90 (95% CI, 0.79 to 0.97). Positive likelihood ratio, 10.01 (95% CI, 4.34 to 23.12). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.04 (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.28). Source: Mehrotra and colleagues.36

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

The sampling method, the positivity threshold for dysplasia in regard to the reference standard, and to what extent examiners were calibrated during interpretation of the index test are unclear.

The investigators conducted the study in a secondary care setting. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

The positivity threshold for the index test included atypical results.

Tissue reflectance and vital staining.

One study informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 102 lesions.28 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard was unclear (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). When a clinician uses tissue reflectance and vital staining, 0% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.00; 95% CI, 0.00 to 0.60). However, 76% of lesions without the disorder will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.84) (eFigure 5,28 available online at the end of this article). See Table 3,28 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 3:

Tissue reflectance and vital staining adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident, seemingly innocuous, or nonsuspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 0 (0 to 150) | 0 (0 to 1,200) | 102 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 250 (100 to 250) | 2,000 (800 to 2,000) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 75,810 (65,835 to 83,790) | 74,480 (64,680 to 82,320) | 102 (1) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 23,940 (15,960 to 33,915) | 23,520 (15,680 to 33,320) | ||

Setting: primary care. Sensitivity, 0.00 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.00 to 0.60). Specificity, 0.76 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.84). Positive likelihood ratio, not available. Negative likelihood ratio, 1.32 (95% CI, 1.18 to 1.48). Source: Mehrotra and colleagues.28

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

We judged the patient selection and index test domains as being at high risk of bias.

The investigators conducted the study in a secondary care setting. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

The positivity threshold for the reference test in regard to dysplasia was unclear.

We did not recover any studies on the DTA of vital staining, autofluorescence and tissue reflectance, cytologic testing and vital staining, and tissue reflectance adjuncts. Therefore, we could not include any for the evaluation of seemingly innocuous lesions in the oral cavity.

Evidence on the use of adjuncts in patients with clinically evident lesions suspected to be potentially malignant or malignant.

We identified 44 studies 27,28,30,32–38,40–68,70–74 in which the investigators addressed the DTA of autofluorescence, cytologic testing, vital staining, tissue reflectance, cytologic testing and vital staining, and tissue reflectance and vital staining. eTable 324–70 summarizes the characteristics of the included populations. Investigators conducted all studies in a secondary or tertiary setting with the exception of Rahman and colleagues42. Pooled sensitivity and specificity of adjuncts ranged from 0.31 to 0.95 for the evaluation of these type of lesions.

Autofluorescence.

Seven studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 616 lesions.24–27,29–31 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC, except for the study by Farah and colleagues,25 in which we were unable to elucidate how the authors classified a positive test result.

When a clinician uses autofluorescence, 90% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.00). However, 72% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.35 to 1.00) (eFigures 624–27,29–31 and 7, available online at the end of this article). See Table 4,24–27,29–31 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 4:

Autofluorscence adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 225 (190 to 250) | 1,800 (1,520 to 2,000) | 616 (7) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 25 (0 to 610) | 200 (0 to 480) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 71,820 (34,913 to 99,750) | 70,560 (34,300 to 98,000) | 616 (7) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 27,930 (0 to 64,837) | 27,440 (0 to 63,700) | ||

Setting: Primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76 to 1.00). Pooled specificity, 0.72 (95% CI, 0.35 to 1.00). Positive likelihood ratio, 3.17 (95% CI, 0.85 to 11.80). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.14; (95% CI, 0.03 to 0.64). Sources: Awan and colleagues,24 Farah and colleagues,25 Hanken and colleagues,26 Koch and colleagues,27 Onizawa and colleagues,29 Petruzzi and colleagues,30 and Scheer and colleagues.31

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Patient selection and exclusion from analysis were inappropriate. Poor-quality reporting did not provide sufficient information to judge key risk of bias domains.

The investigators conducted most studies in secondary and tertiary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

Cytologic testing.

Fifteen studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 2,148 lesions.32–35,37–47 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC in most of the studies (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). It was unclear how dysplasia was classified in the study by Navone and colleagues,39 and Rahman and colleagues42 classified mild dysplasia as negative for the target condition.

When a clinician uses cytologic testing, 92% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.98). However, 94% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.88 to 0.99) (eFigures 832–35,37–47 and 9, available online at the end of this article). See Table 5,32–35,37–47 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 5:

Cytologic adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant, and timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be performed. | 230 (215 to 245) | 1,840 (1,720 to 1,960) | 2,148 (15) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 20 (5 to 35) | 160 (40 to 280) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 93,765 (87,780 to 98,753) | 92,120 (86,240 to 97,020) | 2,148 (15) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 5,985 (997 to 11,970) | 5,880 (980 to 11,760) | ||

Setting: primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86 to 0.98). Pooled specificity, 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88 to 0.99). Positive likelihood ratio, 14.18 (95% CI, 5.82 to 34.59). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.08 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.18). Sources: Delavarian and colleagues,32 Fontes and colleagues,33 Kammerer and colleagues,34 Koch and colleagues,35 Mehrotra and colleagues,37 Nanayakkara and colleagues,38 Navone and colleagues,40 Navone and colleagues,39 Ng and colleagues,41 Rahman and colleagues,42 Scheifele and colleagues,43 Sciubba,44 Seijas-Naya and colleagues,45 Svirsky and colleagues,46 and Trakroo and colleagues.47

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Patient selection and exclusion from analysis were inappropriate, index and reference tests were conducted in an unblinded fashion, and in some cases the time between index and reference test was greater than 2 weeks. It was unclear whether all participants received the reference test. Poorquality reporting did not provide sufficient information to judge key risk of bias domains.

Investigators conducted most studies in secondary and tertiary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

The positivity threshold for the reference test included from mild dysplasia to cancer in all studies except for those of Kammerer and colleagues,34 Navone and colleagues,39 and Rahman and colleagues.42 The positivity threshold included atypia for Rahman and colleagues,42 Scheifele and colleagues43 (10/96), Sciubba (52/298), and Svirsky and colleagues.46 Parentheses indicate the number of atypical results out of the total (atypical þ positive results).

Vital staining.

Fifteen studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 1,453 lesions.42,48–61 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC in all studies except for those of Rahman and colleagues,42 Singh and Shukla,61 and Cheng and Yang,53 (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). Rahman and colleagues42 classified mild dysplasia as negative, and Singh and Shukla61 considered all dysplasia negative. It was unclear how Cheng and Yang53 classified the varying grades of dysplasia.

When a clinician uses vital staining, 87% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.94). However, 71% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.82) (eFigures 1042,48–61 and 11, available online at the end of this article). See Table 6,42,48–61 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 6:

Vital staining adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 217 (200 to 235) | 1,740 (1,600 to 1,880) | 1,453 (15) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 33 (15 to 50) | 260 (120 to 400) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 70,823 (60,848 to 81,795) | 69,580 (59,780 to 80,360) | 1,453 (15) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 28,927 (17,955 to 38,902) | 28,420 (17,640 to 38,220) | ||

Setting: primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80 to 0.94). Pooled specificity, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.61 to 0.82). Positive likelihood ratio, 3.04 (95% CI, 2.06 to 4.48). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.18 (95% CI, 0.10 to 0.32). Sources: Allegra and colleagues,48 Awan and colleagues,49 Cancela-Rodriguez and colleagues,50 Chaudhari and colleagues,51 Chen and colleagues,52 Cheng and Yang,53 Du and colleagues,54 Mashberg,55 Nagaraju and colleagues,56 Onofre and colleagues,57 Rahman and colleagues,42 Silverman and colleagues,58 Singh and Shukla,61 Upadhyay and colleagues,59 and Warnakulasuriya and Johnson.60

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Patient selection and exclusion from analysis were inappropriate. It was unclear whether all participants received the reference test. Poor-quality reporting did not provide sufficient information to judge key risk of bias domains.

Investigators conducted most studies in secondary and tertiary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

Tissue reflectance.

Five studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 390 lesions.62–66 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC in all studies with the exception of those of Chainani-Wu and colleagues,62 Ujaoney and colleagues,65 and Farah and McCullough63(eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article). Ujaoney and colleagues65 classified mild dysplasia as negative, and Chainani-Wu and colleagues62 classified mild and moderate dysplasia as negative. It was unclear how Farah and McCullough63 classified dysplasia.

When a clinician uses tissue reflectance, 72% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.81). However, 31% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.36) (eFigures 1262–66 and 13, available online at the end of this article). See Table 7,62–66 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 7:

Tissue reflectance adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 180 (155 to 203) | 1,440 (1,240 to 1,620) | 390 (5) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 70 (47 to 95) | 560 (380 to 760) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 30,923 (24,938 to 35,910) | 30,380 (24,500 to 35,280) | 390 (5) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 68,827 (63,840 to 74,812) | 67,620 (62,720 to 73,500) | ||

Setting: primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.72 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 to 0.81). Pooled specificity, 0.31 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.36). Positive likelihood ratio, 1.04 (95% CI, 0.90 to 1.20). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.63 to 1.30). Sources: Awan and colleagues,66 Chainani-Wu and colleagues,62 Farah and McCullough,63 McIntosh and colleagues,64 and Ujaoney and colleagues.65

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Only 1 of 4 studies had a low risk of bias. Poor-quality reporting did not provide sufficient information to judge key risk of bias domains.

Investigators conducted all studies in secondary and tertiary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

Cytologic testing and vital staining.

Two studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 139 lesions.69,70 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC in Gupta and colleagues,70 but Guneri and colleagues69 classified only severe dysplasia as positive (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article).

When a clinician uses cytologic testing and vital staining, 95% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.99). However, 68% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.78) (eFigures 1469,70 and 15, available online at the end of this article). See Table 8,69,70 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 8:

Cytologic testing and vital staining adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and a timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be carried out. | 238 (215 to 248) | 1,900 (1,720 to 1,980) | 139 (2) | Very low¶,#,**,†† |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 12 (2 to 35) | 100 (20 to 280) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 67,830 (55,860 to 77,805) | 66,640 (54,880 to 76,440) | 139 (2) | Very low¶,#,**,†† |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 31,920 (21,945 to 43,890) | 31,360 (21,560 to 43,120) | ||

Setting: primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.95 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86 to 0.99). Pooled specificity, 0.68 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.78). Positive likelihood ratio, 2.97 (95% CI, 2.14 to 4.12). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.07 (95% CI, 0.02 to 0.22). Sources: Guneri and colleagues69 and Gupta and colleagues.70

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Poor-quality reporting prevented us from assessing risk of bias for key domains.

Investigators conducted all studies in secondary and tertiary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

There was a small sample size of only 139 lesions.

Tissue reflectance and vital staining.

Four studies informed this comparison with the investigators evaluating data from 307 lesions.62,65,67,68 The positivity threshold for the criterion standard included from mild dysplasia to OSCC in all studies with the exception of those of Ujaoney and colleagues65 and Chainani-Wu and colleagues.62 Ujaoney and colleagues65 classified mild dysplasia as negative, and Chainani-Wu and colleagues62 classified mild and moderate dysplasia as negative (eTable 10,24–70 available online at the end of this article).

When a clinician uses tissue reflectance and vital staining, 81% of lesions with the target condition will be identified correctly as positive by using the adjunct (sensitivity, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.89). However, 69% of lesions without the target condition will be identified correctly as negative by using the adjunct (specificity, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.63 to 0.75) (eFigures l662,65,67,68 and 17, available online at the end of this article). See Table 9,62–68 which includes additional absolute measures calculated using an illustrative PMD and OSCC prevalence of 2.0%.

TABLE 9:

Tissue reflectance and vital staining adjuncts to evaluate clinically evident suspicious lesions.*

| TEST RESULT | DOWNSTREAM CONSEQUENCES | EFFECT PER 100,000 PATIENTS TESTED (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL [CI]) | NUMBER OF LESIONS (STUDIES) | QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE (GRADE)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence 0.25%† | Prevalence 2%‡ | ||||

| True Positives (Patients With Need for Biopsy) | Patients will be correctly identified as having a potentially malignant lesion, and timely referral to a specialist or biopsy will be performed. | 203 (178 to 223) | 1,620 (1,420 to 1,780) | 307 (4) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Negatives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Not Having Need for Biopsy) | Appropriate diagnostic would be missed, worsening the prognosis of the disease. | 47 (27 to 72) | 380 (220 to 580) | ||

| True Negatives (Patients Without Need for Biopsy) | Patients will receive reassurance that they do not have a potentially malignant or malignant disorder. | 68,828 (62,843 to 74,813) | 67,620 (61,740 to 73,500) | 307 (4) | Low¶,#,** |

| False Positives (Patients Incorrectly Classified as Having Need for Biopsy) | Patients would be incorrectly identified as having a potentially malignant or malignant disorder and would undergo additional unnecessary testing and biopsy. | 30,922 (24,937 to 36,907) | 30,380 (24,500 to 36,260) | ||

Setting: primary care. Pooled sensitivity, 0.81 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71 to 0.89). Pooled specificity, 0.69 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.75). Positive likelihood ratio, 2.62 (95% CI, 2.10 to 3.27). Negative likelihood ratio, 0.27 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.44). Sources: Chainani-Wu and colleagues,62 Epstein and colleagues,67 Mojsa and colleagues,68 and Ujaoney and colleagues.65

We estimated the prevalence by using data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (300,682 people living with oral cavity and pharynx cancer in the United States in 2013) and the 2010 census data for adults 45 years or older collected by the US Census Bureau.

The panel provided illustrative prevalence as an estimation of the number of histopathologic diagnoses from dysplasia to cancer.

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Three of 4 studies showed high risk of bias in patient selection and the application of the index test.

Investigators conducted all studies in secondary care settings. Most patients had a higher probability of having a malignant or potentially malignant disorder.

Sensitivity analyses.

eTables 11 through 1432–35,37–61,69 and Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article) provide information about the sensitivity analyses.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results.

We planned this review and analysis assuming that all commercially available adjuncts may have the potential to assist primary care clinicians in evaluating a patient,s need for referral to a specialist or need for biopsy of lesions that exhibit varying degrees of suspiciousness of malignancy (eFigures 18–21). Many of these adjuncts are marketed heavily for their potential usefulness in early detection of target conditions in patients with and without clinically evident lesions.

In primary care, the prevalence of PMDs and OSCC is low (approximately between 0.25% to 2.0% on the basis of our estimation).81,82 This low prevalence means that clinicians, main role in such settings would be ruling out the presence of target conditions, distinguishing seemingly innocuous lesions that are likely reactive or inflammatory in nature (most of them) from those that require further testing, including biopsy or referral. However, for clinicians in secondary and tertiary care settings (specialists), the main goal is actually the opposite: ruling in the presence of a target condition. One desirable characteristic of an adjunct intended to be used in a primary care setting is having a high sensitivity to minimize the proportion of false-negative results to avoid missing patients requiring biopsy or referral—in other words, avoiding sending patients home with a negative result and, therefore, the assumption that no biopsy or referral is needed when, in reality, they actually have a PMD or OSCC. The other desirable characteristics of an adjunct intended to be used in a primary care setting are being inexpensive and being minimally invasive.

According to our analysis, if a clinician uses cytologic testing to identify the target condition in a group of 100,000 people with clinically evident lesions (of whom 250 truly have the target condition), 20 of them would be classified incorrectly as not needing biopsy (false-negative result), and 5,985 people would be identified incorrectly as needing biopsy or referral (false-positive result). If vital staining were used, 33 people would be classified incorrectly as not needing biopsy, and 28,927 would be identified incorrectly as needing biopsy or referral. If an autofluorescence method were used, 25 people would be classified incorrectly as not needing biopsy, and 27,930 would be identified incorrectly as needing biopsy or referral. Finally, if tissue reflectance adjuncts were used, 70 people would be classified incorrectly as not needing biopsy, and 68,827 would be identified incorrectly as needing biopsy or referral. Therefore, all included adjuncts (cytologic testing, autofluorescence, tissue reflectance, and vital staining) would result in more false-positive than true-positive results if used in primary care settings. All of these findings were supported by low-quality to very low-quality evidence. Of all adjuncts being assessed, cytologic testing seems to have the highest accuracy.

Quality of the evidence.

Although we were interested in the use of adjuncts in primary care settings, most of the included studies were conducted in secondary and tertiary care settings such as hospitals or specialty clinics. Furthermore, though all adjuncts assessed are commercially available in the United States, most of the included studies were conducted in other countries. The relative skills of practitioners, assessment of outcomes, and positivity thresholds for both adjuncts and criterion standards were notably diverse. The assessment of the quality of evidence ranged from low to very low for most outcomes, where the main issues to reduce our confidence were limitations in study design and indirectness.

Comparison with Cochrane reviews used for the update and other non-cochrane systematic review results.

For a description of the differences introduced in this review compared with the 2 preexisting Cochrane reviews informing this work, see Appendix 2 (available online at the end of this article).

Strengths and limitations of this review.

Strengths of this review include the rigor of the methodology, including screening of potentially eligible studies and data extraction being conducted in duplicate and independently by 2 reviewers; the use of preexisting, high-quality systematic reviews allowing us to elaborate on a fruitful collaboration (methodology, data analysis, and sharing of data) with the Cochrane Oral Health Group; the use of DTA pooled estimates; the use of the GRADE approach to determine our certainty in the evidence; and the use of a sensitivity analysis to determine the robustness of results from primary studies with issues of verification bias. This review also has its limitations. Although the most informative evidence about the benefits and harms of using adjuncts in the clinical workup for PMDs and OSCC should come from patient-important outcomes, we were unable to find this type of data. Instead, we were able only to summarize DTA estimates and illustrative downstream consequences. A second limitation is that we identified only studies conducted in secondary and tertiary care settings, whereas the original clinical questions referred to the use of these adjuncts in primary care, introducing issues of indirectness where the generalizability of the results is limited because the populations, adjuncts, and outcomes of interest differ from those available in the literature. Finally, most outcomes were affected by issues of risk of bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, adjuncts showed limited DTA when contextualized to be used in primary care settings. The main concerns are the high rate of false-positive results and serious issues of risk of bias and indirectness of the evidence. Low-quality evidence suggests that cytologic testing seems to be the most accurate adjunct among those included in this review. Biopsy and histopathologic assessment remain the single definitive test to diagnose PMDs and OSCC through detecting dysplasia. In relation to PVPs, anxiety and denial seem to be key barriers to diagnosis and initiating treatment. Clinicians should remain skeptical about the potential benefit that these devices may offer in practice. ■

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the special contributions of Jeff Huber, MBA, Scientific Content Specialist, ADA Center for Evidence-based Dentistry, and Laura Pontillo, Coordinator, ADA Library & Archives.

The authors also acknowledge the following people, committees, and organizations: Tanya Walsh, PhD, MSc, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, and Janet Clarkson, BDS, PhD, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom, from the Cochrane Collaboration,s Cochrane Oral Health Group; the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs Evidence-Based Dentistry Subcommittee; Thomas W. Braun, DMD, PhD, MS, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Ruth Lipman, PhD, Marcelo Araujo, DDS, MS, PhD, and Jim Lyznicki, MS, MPH, from the ADA Science Institute, ADA, Chicago IL; Adam Parikh and Alexandra Fushi, MPH, dental students at Midwestern University College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, Downers Grove, Illinois; Eugenio D. Beltrán-Aguilar, DMD, DrPH, DB Consulting Group, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Barbara F. Gooch, DMD, MPH, DB Consulting Group, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Lorena Espinoza, DDS, MPH, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Elizabeth A. Van Dyne, MD, MPH, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Mona Saraiya, MD, MPH, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; the ADA Council on Dental Benefit Programs; the ADA Council on Dental Practice; the ADA Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention; the American Academy of Family Physicians; the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Research and Scientific Affairs Committee; the American Academy of Oral Medicine; the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; the American Association of Public Health Dentistry; the American Head and Neck Society; the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors; the Head and Neck Cancer Alliance; the International Academy of Oral Oncology; the NIDCR; Support for People with Oral and Head and Neck Cancer; the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center; and the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclosures. Dr. Lingen has received research funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). In addition, he is the editor-in-chiefofOral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and the vice president of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Dr. Agrawal has received funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct research focused on head and neck cancer genetics and tumor DNA in the saliva and plasma of patients with head and neck cancer. He is also on the editorial board of Scientific Reports. Dr. Chaturvedi has received funds from the Intramural Program of the NCI to conduct research focused on the natural history of oral cancer precursor lesions. He is an employee at the NCI NIH, and authorship in this guideline is considered his opinion and not that of the NCI NIH. Dr. Cohen is a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Human Longevity, Merck, Merck Serono, and Pfizer. Dr. D,Souza has received funds from the NIDCR. Dr. Kalmar has received funds from The Ohio State University to conduct research on determining surgical margins by using VELscope (LED Medical Diagnostics). Dr. Kerr has received funds from the NIDCR to conduct research focused on increasing oral cancer screening by dentists. Dr. Patton is a coeditor of the second edition of The ADA Practical Guide to Patients With Medical Conditions. She also has received funds from the NIDCR to conduct research focused on a clinical registry of dental outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer. In addition, she is the oral medicine section editor of Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and she is vice president of the American Academy of Oral Medicine. Dr. Sollecito is the director and treasurer of the American Board of Oral Medicine, a site visitor for the Commission on Dental Accreditation, and a regional director for the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh. He also has received funds from the NIDCR to conduct research focused on a clinical registry of dental outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer. Ms. Tampi, Mrs. Urquhart, and Dr. Carrasco-Labra have no disclosures to report.

Methodologists from the ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry led the development and authorship of the systematic review and clinical practice guideline in collaboration with the expert panel. The ADA Council on Scientific Affairs commissioned this work.

ABBREVIATION KEY.

- ADA

American Dental Association

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CVTE

Conventional visual and tactile examination

- DTA

Diagnostic test accuracy

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- OSCC

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PMD

Potentially malignant disorder

- PVPs

Patients’ values and preferences

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data related to this article can be found at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2017.08.045.

Contributor Information

Mark W. Lingen, University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, IL..

Malavika P. Tampi, Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry, Science Institute, American Dental Association, 211 E. Chicago Ave, Chicago, IL 60611.

Olivia Urquhart, Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry, Science Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL..

Elliot Abt, Department of Oral Medicine, University of Illinois College of Dentistry; immediate past chair, American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs; and maintains a private practice in general dentistry, Skokie, IL..

Nishant Agrawal, Department of Surgery, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL..

Anil K. Chaturvedi, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD..

Ezra Cohen, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego; the associate director, Translational Science, Moores Cancer Center; and the codirector, Head and Neck Cancer Center of Excellence, San Diego, CA..

Gypsyamber D’Souza, Departments of Epidemiology, International Health, and Otolaryngology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD..

JoAnn Gurenlian, Department of Dental Hygiene, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID..

John R. Kalmar, Division of Oral Pathology and Radiology, The Ohio State University College of Dentistry, Columbus, OH..

Alexander R. Kerr, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY..

Paul M. Lambert, Department of Surgery, Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH; clinical associate professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH; and a past trustee, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Meridian, ID..

Lauren L. Patton, Department of Dental Ecology; and the director, General Practice Residency, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC..

Thomas P. Sollecito, Oral Medicine, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA..

Edmond Truelove, Department of Oral Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA..

Laura Banfield, Health Sciences Library, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada..

Alonso Carrasco-Labra, Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL; Evidence-Based Dentistry Unit and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile..

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlander N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. , eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/ Accessed March 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouquot JE. Common oral lesions found during a mass screening examination. JADA. 1986;112(1):50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macey R, Walsh T, Brocklehurst P, et al. Diagnostic tests for oral cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients presenting with clinically evident lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5: CD 010276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh T, Liu JL, Brocklehurst P, et al. Clinical assessment to screen for the detection of oral cavity cancer and potentially malignant disorders in apparently healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11: CD 010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rethman MP, Carpenter W, Cohen EEW, et al. ; for the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Screening for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding screening for oral squamous cell carcinomas. JADA. 2010;141(5):509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton LL, Epstein JB, Kerr AR. Adjunctive techniques for oral cancer examination and lesion diagnosis: a systematic review of the literature. JADA. 2008;139(7):896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, Speight PM. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(1): 10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu J, Brozek JL, Terracciano L, et al. Application of GRADE: making evidence-based recommendations about diagnostic tests in clinical practice guidelines. Implement Sci. 2011;6:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]