Abstract

Introduction:

Musculoskeletal oncology is a subspecialty of orthopaedics with few fellowship-training locations. Although orthopaedic oncologists comprise a minority within the field of orthopaedic surgery, most work at academic centers and serve in leadership roles with notable impact on patients and the training of residents. This article investigates the objective impact orthopaedic oncologists have regarding resident operative case volume and performance on in-training examinations.

Methods:

The William Beaumont Army Medical Center and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center of El Paso combined orthopaedic residency program's case logs and Orthopaedic In-Training Examination (OITE) scores between 2013 and 2018 were reviewed. This provided 3 academic years of data before and after an orthopaedic oncology faculty member arrived in 2016. The case volume and OITE examination performance before and after the addition of the orthopaedic oncology faculty member were compared.

Results:

After the addition of an orthopaedic oncology faculty member, a significant increase was observed in the program's OITE overall correctly answered questions (171.30 versus 181.03, P = 0.004) and oncology subsection percentile (56th to the 66th percentile, P = 0.038). An increase was also observed in resident oncology case volume from 29 oncology cases per year to 138 cases on average (P = 0.022).

Discussion:

The addition of a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist results in increased exposure to orthopaedic oncology cases and improved resident performance on the OITE. This may correlate to improved American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons Part I pass rates and improved overall resident satisfaction.

An orthopaedic oncology surgeon specializes in the treatment of bone and soft-tissue neoplasms, developmental dysplasia, and tumor-like conditions. In the United States, orthopaedic oncology is considered a relatively new subspecialty. In 1977, a small group of clinicians, including orthopaedic surgeons and pathologists, founded the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society with only three orthopaedic oncology fellowships available at that time.1 Although this society began with only a handful of practitioners, it has grown to approximately 200 recognized members2 and expanded to offer a total of 14 musculoskeletal tumor fellowship locations in the United States in 2019.3 Although there has been considerable growth over the past 50 years, orthopaedic oncology fellowships typically produce no more than 12 to 15 new surgeons each year,4 representing 1.5% of all specialty trained orthopaedic surgeons in the United States.5

Although scarce in numbers compared with other subspecialists, orthopaedic oncologists have a notable impact on patient care and resident education. The American Cancer Society estimates that 13,130 new soft-tissue sarcomas and 3,600 new bone cancers will be diagnosed in the year 2020, with 5,350 people succumbing to a soft-tissue sarcoma and 1,720 to bone cancer.6,7 Orthopaedic oncologists treat more than two-thirds of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas in the United States2 and furthermore offer unique perspectives and educational opportunities to academic programs that would otherwise be unavailable. These include, but are not limited to, expanded breadth of surgical techniques and approaches, exposure to rare pathology, and interdepartmental collaborations with the use of multidisciplinary specialty teams for patient care.

Orthopaedic surgery resident training consists of didactic education, clinical management, and surgical practice through repetitive case experience within the operating room. Residents are expected to help patients understand their musculoskeletal conditions and assist in making informed decisions regarding management. Orthopaedic oncology–related patient educational materials are often difficult for patients to comprehend,8 and a baseline of experience in musculoskeletal oncology is paramount for optimal patient care. Lack of familiarity in abnormal skeletal radiographs result in undue patient and provider anxiety and unnecessary urgent referrals to orthopaedic oncologists.9,10 With notable variability in resident case volume in orthopaedic oncology11 and considering the devastating consequences of mismanagement,12,13 appropriate baseline training with an orthopaedic oncologist should be required for all orthopaedic surgery residents.

The objective educational impact of a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist on an orthopaedic surgery residency program has not been established. Although indisputable benefits are present as previously described, objective measures are also present that can be used to determine educational impact. The purpose of this study was to determine the changes of Orthopaedic In-Training Examination (OITE) scores and case logs before and after the addition of a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist to a residency program.

Methods

William Beaumont Army Medical Center and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center of El Paso share a 5-year orthopaedic surgery residency in El Paso, Texas. The program includes both civilian and military residents. The combined residency did not have a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist on staff from 2013 to 2015, comprising 3 total academic training years. At the beginning of the academic year in 2016, a fellowship-trained musculoskeletal oncologist was hired, with immediate incorporation into the residency program.

The residency program participates in the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Orthopaedic In-Training Examination (OITE) every year. The OITE score report includes the total number of questions answered correctly, the correlated percentile, and a breakdown of each specialty subsection. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons OITE scores were queried between 2013 and 2018 to determine individual and program overall and subspecialty scores. The number of correctly answered questions and percentile ranks were reported for overall and the oncology-specific subsection.

The American Council of Graduate Medical Education mandates that each residency program maintain accurate case reports via an electronic system. Orthopaedic oncology cases were queried electronically on the American Council of Graduate Medical Education program website from the 2013 to 2018 academic years.

Independent sample Student t-tests were used to compare means of continuous and ordinal variables, and P values less than 0.05 were considered to represent a significant difference. For variables with the Levene Test for Equality of Variances less than 0.05, equal variance was not assumed. All analysis was performed in SPSS version 25 (IBM Released 2018. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 25.0.; IBM).

Results

A total of 68 total OITE score reports were available before the arrival of the fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist (FTO) and 75 score reports after their arrival. The differences in individual postgraduate year (PGY) groups' overall number of questions correct before and after the addition FTO were not statistically significant with the exception of the PGY-5 cohort (185.07 versus 197.87, P = 0.006; Table 1). The average number of correct questions from the program significantly increased (171.30 versus 181.03, P = 0.004). Although the PGY-5 cohort and the program answered more questions correctly after the addition of a FTO, not a significant increase was observed in overall national percentile ranks, respectively (80.1st percentile versus 82nd percentile and 71st percentile versus 75th percentile, P = 0.133 and 0.624, respectively; Table 1).

Table 1.

Overall OITE Questions Correct and Percentile Scores, by Postgraduate Year and Program, 2013 to 2018

| PGY-Level | All Questions (No. of Correct Questions) | All Questions (Corresponding Percentile) | ||||

| Pre-FTO | Post-FTO | Pa | Pre-FTO | Post-FTO | Pa | |

| PGY-1 | 148.29 | 158.80 | 0.075 | 36.8 | 32.5 | 0.463 |

| PGY-2 | 167.60 | 172.53 | 0.322 | 57.6 | 52.0 | 0.355 |

| PGY-3 | 178.69 | 187.67 | 0.051 | 72.7 | 75.3 | 0.668 |

| PGY-4 | 179.36 | 188.27 | 0.320 | 74.6 | 85.6 | 0.111 |

| PGY-5 | 185.07 | 197.87 | 0.006 | 80.1 | 82.0 | 0.133 |

| Program total | 171.30 | 181.03 | 0.004 | 71.4 | 75.5 | 0.255 |

FTO = fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist, PGY = postgraduate year

Based on independent, two-tailed Student t-test. All were shown to have equal variance through the Levene test for equality of variances.

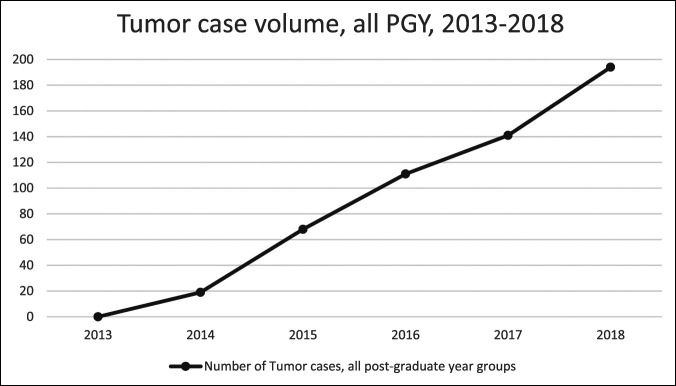

The differences in individual postgraduate year (PGY) groups and the program oncology-specific questions answered correctly before and after the addition FTO were not notably different (Table 2). However, the program overall increased 10 national percentile points on the oncology-specific subsection of the OITE (55.9th percentile versus 65.9st percentile, P = 0.03; Table 2). In addition, the combined all-resident tumor case volume increased from an average of 29 cases per year before the addition of a tumor surgeon to 138 per year after a 475% increase (P = 0.022; Figure 1).

Table 2.

OITE Oncology-Subsection Questions Correct and Percentile Scores, by Postgraduate Year and Program, 2013 to 2018

| PGY-Level | All Questions (No. of Correct Questions) | All Questions (Corresponding Percentile) | ||||

| Pre-FTO | Post-FTO | Pa | Pre-FTO | Post-FTO | Pa | |

| PGY-1 | 51.80 | 46.70 | 0.340 | 50.6 | 68.7 | 0.122 |

| PGY-2 | 58.00 | 54.00 | 0.386 | 53.6 | 65.7 | 0.201 |

| PGY-3 | 60.69 | 62.80 | 0.756 | 54.6 | 63.2 | 0.461 |

| PGY-4 | 66.73 | 65.47 | 0.807 | 64.4 | 64.3 | 0.992 |

| PGY-5 | 65.71 | 70.47 | 0.275 | 58.8 | 67.6 | 0.395 |

| Program total | 60.37 | 59.89 | 0.853 | 55.9 | 65.9 | 0.038 |

FTO = fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist, PGY = postgraduate year

Based on independent, two-tailed Student t-test. All were shown to have equal variance through the Levene test for equality of variances.

Figure 1.

Graph demonstrating the tumor case volume, by postgraduate year, 2013 to 2018.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the objective impact of a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist on an academic orthopaedic surgery residency. The addition of a fellowship-trained orthopaedic oncologist notably increased the program's OITE overall questions correct and oncology-specific national percentile scores. Unsurprisingly, a notable increase was also observed in oncology cases logged. Therefore, orthopaedic oncologists notably improve resident education and surgical experience, regarding tumor-specific metrics, in an objective manner.

One of the most important metrics to evaluate an individual program's academic standing is the program's ABOS pass rate. OITE scores have shown to be predictors of passing rates on the ABOS Part I examination.14,15,16,17,18 A stepwise increase is observed in correlation from PGY-2 through PGY-5 between the OITE scores and American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Part 1 passing rates.14 Over half of residents in their PGY-5 year who score in the lowest quartile fail their ABOS Part I examination.14,15 Although our program's PGY-5 national percentile scores did not notably improve with the addition of an orthopaedic oncologist, this is likely because of the ceiling effect because they were already averaging in the top quartile before the arrival of the new faculty member. However, the overall number of OITE questions answered correctly increased with a corresponding increase in the program's oncology-specific national percentile scores, highlighting the objective educational benefit of the orthopaedic oncologist. Although this academic improvement could not be contributed to a specific PGY level increase in oncology-specific percentile scores, this is likely because of the loss of power from subgroup analysis.

Having an orthopaedic oncologist improved the educational experience of residents as demonstrated by increased orthopaedic case volume and improved OITE scores. These improvements likely resulted from multiple facets. First, the program was able to establish a dedicated 10-week oncology rotation for all residents. This rotation provided 2 surgical days, 2 clinical days, and one departmental academic day each week. Second, increased interdepartmental collaboration was observed through tumor board meetings with radiologists, pathologists, and medical oncologists. This interdepartmental collaboration has shown to be paramount in the decision-making process within orthopaedic oncology,19 and the orthopaedic resident on service was present and actively involved in these meetings. The off-service residents were also regularly exposed to oncology when cases were presented at morning report. Finally, the orthopaedic oncologist served a leadership role in the hospital, consistent with most others within the orthopaedic oncology subspecialty2 and was able to secure additional departmental funding for residents to attend yearly musculoskeletal pathology seminars. The orthopaedic oncologist also encouraged and provided mentorship to residents, which has been shown to improve overall resident satisfaction.20

The biggest limitation of this study is the involvement of only one program over a 6-year period. In addition, one specific class within the program was consistently high scoring on the OITE examination from early on in their residency and detecting changes from this class were limited because of the ceiling effect. The next step in research would be to expand the number of years included and/or include multiple residency programs.

In conclusion, this study found an overall improved educational experience for residents after the addition of an orthopaedic oncology surgeon to staff. We found a notable increase in the number of orthopaedic oncology cases and improvement on the oncology subsection of the OITE. An orthopaedic oncologist also facilitates interdepartmental communication and outside educational opportunities and can serve as a valuable addition to an orthopaedic surgery residency program.

Footnotes

None of the following authors or any immediate family member has received anything of value from or has stock or stock options held in a commercial company or institution related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article: Dr. Wells, Dr. Eckhoff, Dr. Schneider, Dr. Kafchinski, Dr. Dunn, and Dr. Gonzalez.

General Disclosure: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of William Beaumont Army Medical Center, Department of the Army, Defense Health Agency, or the US Government.

References

- 1.Enneking WF: An abbreviated history of orthopaedic oncology in North America. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;374:115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White J, Toy P, Gibbs P, Enneking W, Scarborough M: The current practice of orthopaedic oncology in North America. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2840-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Post Graduate Orthopaedic Fellowship Directory 2019. https://www7.aaos.org/education/fellowshipbook/fellowshipsearch.aspx. Published 2019. Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller BJ, Rajani R, Leddy L, Carmody Soni EE, White JR, Initiative MOR: How much tumor surgery do early-career orthopaedic oncologists perform? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:695-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Orthopaedic Practice in the U.S. 2018. https://www5.aaos.org/aaoscensus/?ssopc=1. Published 2018. Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Soft Tissue Sarcomas. https://www5.aaos.org/aaoscensus/?ssopc=1. Published 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Soft Tissue Sarcomas. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bone-cancer/about.html. Published 2020. Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah AK, Yi PH, Stein A: Readability of orthopaedic oncology-related patient education materials available on the internet. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;23:783-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Musculoskeletal Tumor Society Committee of Evidence Based Medicine. Guidelines for Specialist Referral in Newly Identified Bone Lesions. https://safe.menlosecurity.com/doc/docview/viewer/docN19F9F163042Ef1cc30bd635ca0ff4c8f13cab8a2cd6bda712f313c04fb812060c653a583fa56. Published 2018. Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller BJ: Use of imaging prior to referral to a musculoskeletal oncologist. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019;27:e1001-e1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil JA, Daniels AH, Weiss AP: Variability in surgical case volume of orthopaedic surgery residents: 2007 to 2013. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mankin HJ, Mankin CJ, Simon MA: The hazards of the biopsy, revisited. Members of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:656-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errani C, Traina F, Perna F, Calamelli C, Faldini C: Current concepts in the biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:538152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougherty PJ, Walter N, Schilling P, Najibi S, Herkowitz H: Do scores of the USMLE step 1 and OITE correlate with the ABOS Part I certifying examination?: A multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2797-2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herndon JH, Allan BJ, Dyer G, Jawa A, Zurakowski D: Predictors of success on the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery examination. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2436-2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyrstad BW, Pope D, Milbrandt JC, Beck RT, Weinhoeft AL, Idusuyi OB: Predictive measures of a resident's performance on written Orthopaedic Board scores. Iowa Orthop J 2011;31:238-243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein GR, Austin MS, Randolph S, Sharkey PF, Hilibrand AS: Passing the boards: Can USMLE and orthopaedic in-training examination scores predict passage of the ABOS Part-I examination? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1092-1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Risner B, Nyland J, Crawford CH, Crawford C, Roberts CS, Johnson JR: Orthopaedic in-training examination performance: A nine-year review of a residency program database. South Med J 2008;101:791-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons TW, Frink SJ, Campbell SE: Musculoskeletal neoplasia: Helping the orthopaedic surgeon establish the diagnosis. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2007;11:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flint JH, Jahangir AA, Browner BD, Mehta S: The value of mentorship in orthopaedic surgery resident education: The residents' perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1017-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]