Abstract

Background

Post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) pose a high burden for individuals and societies. Although prevalence rates are rather low, high co-occurrence rates and overall impairments cause deleterious suffering and significant costs. Still, no long-term data on costs and trends in cost developments are available.

Methods

Claims data from a German research database were analysed regarding direct and indirect costs occurring for individuals with incident diagnoses of PTSD. Results were compared to non-exposed average insurants matched on age and gender. Costs were analysed over a 5-year period from 2 years preceding until 3 years following an incident diagnosis of PTSD.

Results

Overall costs for PTSD account for approximately 43,000 EUR per individual, which is three times higher than costs for non-exposed controls. Of these costs, 59% are caused by mental disorders, 18% specifically by PTSD. In the control group, costs for mental disorders account for 19% of total costs. Costs increase by 142% in the year after an incident diagnosis of PTSD but return to the initial level 2 years later. Still, costs are at least twice as high in every year as in those for the comparison group.

Conclusions

Individuals with PTSD seem to suffer from far more impairments in their general health conditions and incur many more costs than average insurants. Most of these seem to be caused by co-occurring mental disorders and show their maximum in the index year. Nevertheless, as costs decrease to their initial level, treatments seem to have counterbalanced the impairments due to PTSD. Thus, treatments for PTSD can be considered as beneficial and their cost-effectiveness should be further investigated.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorders, Health care costs, Claims data, Cost-analysis, Cost-comparison

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) are a critical public health issue with significant impacts on affected individuals, health care systems, and societies. Despite comparatively low prevalence rates of 1.1–2.9% in the European population [1], the disability burden and occurring societal costs associated with PTSD are considered to be high [2]. Individuals suffer from PTSD symptoms for 6 years on average [3] and show a higher risk of suicide [4, 5]. Co-occurrence rates for other mental disorders are estimated at 50–100% [6]. In particular, depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders are considered to be the most prevalent co-occurring mental disorders [4]. Furthermore, individuals with PTSD suffer from high impairments in their overall health condition and co-occurring physical disorders [7, 8]. Common impairments are increased rates of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and autoimmune diseases [9–11]. PTSD often causes incapacity to work and early retirements [12, 13], significant losses in quality of life, and increased utilisations of health care and other social services [2].

In general, mental disorders pose a serious burden to the European population. The overall 12-month prevalence rate of having any mental disorder is estimated at 25.7–38.2%, and their impact on global health impairments continues to increase [1]. Mental disorders cause steep direct (e.g., in- and outpatient treatments, medication) as well as indirect costs (e.g., sickness benefit payments, lost productivity, disability-adjusted life years) [14]. Despite immersive expenses, cost–benefit analyses estimate positive returns of investment for psychotherapeutic treatments specific to several mental disorders [15–19]. Still, not all individuals in need receive adequate treatments or get treated at all [1, 20, 21]. Thus, providing arguments for enabling improvements in health care for mental disorders is necessary [22]. Nevertheless, there is no subsequent clarity about the amount of monetary losses that arise due to mental disorders, and the potential for savings if individuals are treated. Without data to gain a better knowledge of the resulting costs, and to support population-based cost–benefit approaches, the estimates and hence the arguments for providing better health care for mental disorders are rather vague.

For PTSD, little is known about the costs that come along with the disorder’s impairments. As to our knowledge, only a few studies have investigated health care costs due to PTSD. Based on US-American private insurance and Medicaid data, one study estimated direct health care costs of 10,960–18,753 USD per patient per year [23]. A bottom-up study from Northern Ireland on interview data estimated total direct and indirect costs of 317,431,860 EUR for 74,935 affected individuals in the whole national population, which accounts for 4236 EUR for each individual with PTSD [24]. However, comparability of these findings and transferability to other populations and health care systems in other countries are limited due to different estimation approaches.

Thus, this study sought to add evidence regarding the quantity of monetary losses due to PTSD and to compare these costs to those incurred by non-exposed average insurants using a large database of anonymised German statutory health care claims data from the nationwide InGef research database. Data was analysed via all the available outcome measures of direct and indirect costs to estimate incremental costs and potential savings. Trends for cost developments were described to gain a broader view of PTSD and its course of illness before and after the onset of the disorder. Concluding the empirical evidence on the high individual and health burden associated with PTSD, we hypothesised that costs for individuals with PTSD exceed the costs resulting in non-exposed typical insurants after an incident diagnosis.

Methods

Data source

The study was based on anonymised claims data from approximately 70 nationwide statutory health insurance (SHI) providers and more than 8 million individuals included in the InGef research database. In addition to demographic data, the database contains information on dispensed drug prescriptions, outpatient and inpatient services, incapacities to work, and diagnoses. In 2013, the database showed good accordance with the overall German population regarding measures of morbidity, mortality, and drug use [25]. Information about diagnoses and drug prescriptions is available in accordance with the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, German Modification (ICD-10-GM) [26], and the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) code. Results are reported following the Consensus German Reporting Standard for Secondary Data Analyses (STROSA 2) [27].

Study design and population

Selection of the PTSD-group

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of individuals with newly diagnosed PTSD, including data from 2010 until 2017. In a first step, individuals with a prevalent PTSD (ICD-10-GM F43.1) between 2012 and 2014 were identified by the following criteria: individuals had to have either (a) one or more inpatient diagnoses coded as ‘main diagnosis’, (b) two or more outpatient diagnoses stated as ‘secure diagnosis’, or (c) at least one ‘secure’ outpatient diagnosis by a specialist for mental disorders, e.g., a psychotherapist, a psychiatrist, or a neurologist. Incidence was defined as not having had a PTSD diagnosis, according to the abovementioned criteria, 2 years prior to the first PTSD diagnosis (index date) between 2012 and 2014. Only individuals who were fully observable in the database 2 years prior to the first PTSD diagnosis and in the 3 years following their index date or until their death were included. In addition, only individuals aged 18–65 at index date were included in the study population. Individuals were excluded from further analysis if they suffered from (a) organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders, (b) schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, or (c) mental retardation (ICD-10-GM groups F0, F2, and F7) in the period 2 years prior to or in the quarter of their index date.

Selection of a non-exposed control group

To estimate the incremental costs that arise due to PTSD, a no-PTSD affected control group (No-PTSD CG) was identified. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria as for the PTSD-group were applied with the exception of the PTSD diagnosis. We assigned random index dates between 2012 and 2014 to all individuals that had no PTSD diagnosis. Only individuals who were fully observable 2 years prior to the assigned random index date and 3 years after their index date or until their death and who were aged 18–65 were included. Additionally, individuals were excluded if for a F0, F2, or F7 diagnosis in the 2 years preceding or in the quarter of their index diagnosis had been documented. A 1:4 matching by age and gender of individuals with PTSD and non-exposed individuals was conducted, and the resulting sample was used for further analysis.

Baseline characteristics

Sociodemographic data such as gender, age, and insurance status were analysed. Comorbidities in the 2 years prior to the index date according to the ICD-10-GM chapters were assessed to gain a broader view of the overall health status of the study populations. Furthermore, Charlson comorbidity indices (CCI) [28] were determined to estimate individuals’ comorbidity, and, thus, their health status.

Outcomes

Total health care costs

As a primary outcome, the overall amount of costs resulting from health care service utilisation and indirect costs for the German welfare state were analysed. Included were filed medication prescriptions, inpatient and outpatient treatments, sickness benefit payments, and costs due to losses of gross value per day absent. For the latter, average amounts of costs per day absent for every year from 2010 until 2017 as reported by the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [29] were used for calculations and multiplied with the actual number of days spent incapable to work during the respective analysis period. Costs are reported in total and for every outcome, respectively, and in total as well as yearly for the period 2 years prior to the index date, the year after an index diagnosis, and for the following 2 years. Results from both groups were compared to investigate differences in amounts of costs in the year after the onset of PTSD and in the preceding and following 2 years.

Costs resulting from mental disorder-specific health care services

In the second step, data were analysed for all costs due to mental disorders. Only services which were billed due to a documented mental disorder (ICD-10 GM chapter F) within the same hospital case or ambulatory treatment case were included in the cost analysis, as well as sickness benefit payments and reports of incapacities to work. For drug therapies, all prescriptions of ATC-codes beginning with ‘N05’ (psycholeptics) or ‘N06’ (psychoanaleptics) were considered as mental disorder-specific prescriptions in the calculation of mental disorder-related health care costs. Again, costs were compared between groups to analyse differences in costs caused by mental disorders as an estimate for other co-occurring disorders in individuals’ mental health status.

Costs resulting from non-mental disorder-specific health care services

Vice versa, costs that could be identified as not caused by mental disorders were reported using the same method. All services and treatments in which no mental disorder was documented were included in this sub-analysis. Analysis followed the same procedure as for the other outcomes, and costs were compared between groups.

PTSD-specific health care service utilisation

Furthermore, the PTSD-group was analysed for any cost factors due to PTSD after its onset to gain an overview of trends in disorder-specific cost developments for an incident PTSD. Following the same procedure as abovementioned, all services containing a diagnosis of PTSD (ICD-10-GM F43.1) were included in this analysis. As drug therapies cannot be identified as being prescribed explicitly for PTSD or other mental disorders, no PTSD-specific drug costs were estimated.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted, aggregated, and analysed using R version 3.5.0. Analyses were conducted separately for every year during the 2 years preceding an index diagnosis, for the year following an index diagnosis, and for the 2 years after, as well as for the whole 5-year observation period. All descriptive and statistical analyses were conducted regarding total sample sizes, respectively. Differences in totals, i.e., for insurance status and for monetary values, can occur due to multiple data for a respective analysis period, or due to accumulation of overlapping intervals for continuous services.

In accordance with current research trends [30, 31], we focused on descriptive analyses and interpretation of confidence intervals (CI) and effect sizes. These are reported as Cramer’s V or Cohen’s d. For completeness, we also reported Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests with Bonferroni correction for continuous variables. Considering the large sample sizes, differences were considered significant at a level of p < 0.001.

Results

Group characteristics and comorbidities

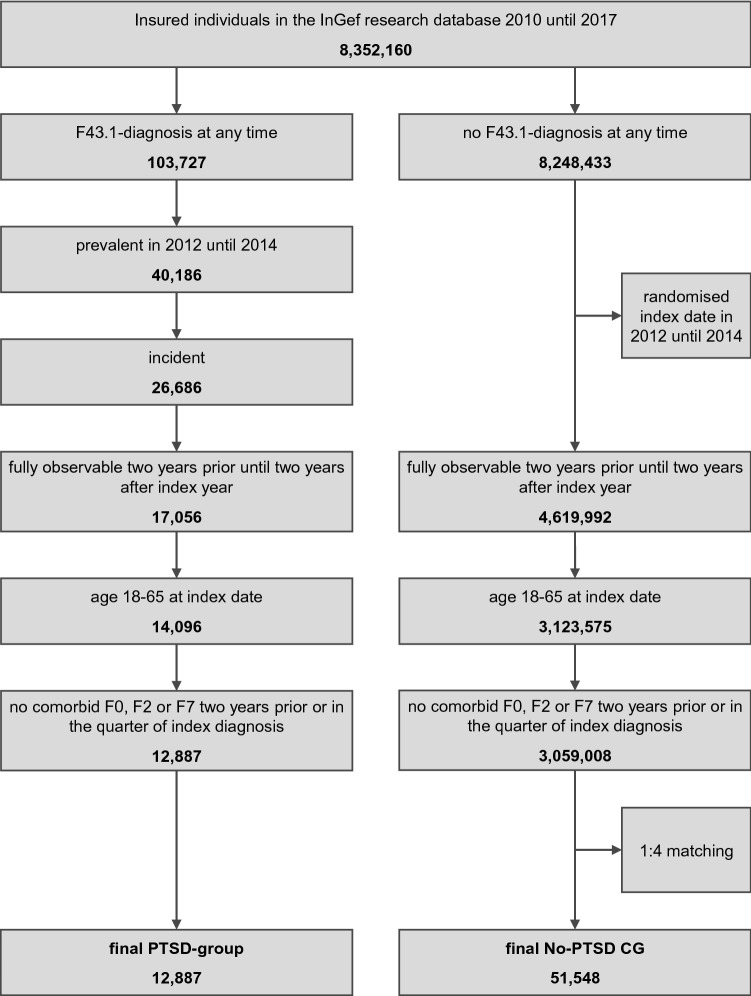

Between 2010 and 2017, anonymised data for approximately 8.4 million individuals were available in the research database. Of these, 103,727 received a diagnosis of PTSD (F43.1) at any time, while 8,248,433 did not. In the PTSD-cohort, 40,186 were identified as prevalent, and 26,686 as an incident between 2012 and 2014. Of these, 17,056 were fully observable in the whole analysis period, and 14,096 were aged 18 to 65. A total of 1,209 individuals were excluded due to a diagnosis of F0, F2, or F7 within 2 years prior to or in the quarter of their index date, which resulted in a final study sample of 12,887 individuals with PTSD. For the No-PTSD CG, after assigning randomised index dates between 2012 and 2014, a total of 4,619,992 individuals fulfilled the criterion for being fully observable 2 years prior until 2 years after the assigned random index year or until their death. Of these, 3,123,575 were aged 18–65, and 3,059,008 remained after exclusion of individuals with an F0, F2, or F7 diagnosis 2 years prior to or in the quarter of their index date. After a 1:4 matching by gender and age, a final sample of 51,548 individuals in the No-PTSD CG remained for further analysis. The flowchart in Fig. 1 illustrates the identification process for both groups.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for sample identification process

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics, CCIs, and comparisons between both groups, respectively. In both groups, persons are aged 42.4 years on average (SD = 11.8) and 73.4% are female. The PTSD-group includes fewer individuals ‘with dependent coverage’ over family members (15.0%; No-PTSD CG: 19.2%) but more individuals with insurance status ‘retired’ (11.1%; No-PTSD CG: 5.0%). Average CCIs are higher in the PTSD-group (0.87; No-PTSD CG: 0.56). χ2-tests for insurance status ‘with dependent coverage’ and ‘retired’ as well as the t test for CCI show significant differences, with small effect sizes for insurance status ‘retired’ (V = 0.10) and CCI (d = 0.28, CI 0.26–0.30).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and CCIs for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548)

| PTSD | No-PTSD CG | Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | V | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.00 | |||

| Female | 9457 (73.4) | 37,828 (73.4) | ||||

| Male | 3430 (26.6) | 13,720 (26.6) | ||||

| Insurance status, n (%) | ||||||

| Member | 10,296 (79.9) | 40,936 (79.4) | 1.44 | 0.231 | 0.00 | |

| With dependent coverage | 1926 (15.0) | 9913 (19.2) | 125.95 | 0.000 | 0.04 | |

| Retired | 1428 (11.1) | 2562 (5.0) | 661.70 | 0.000 | 0.10 | |

| t | p | d | CId | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.37 (11.8) | 42.37 (11.8) | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 |

| CCI, mean (SD) | 0.87 (1.4) | 0.56 (1.1) | − 23.84 | 0.000 | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

CCI Charlson comorbidity index, n sample size, χ2 Chi2-test statistic, tt test statistic, p significance value, V Cramer’s V, d Cohen’s d, CI 95% confidence interval

Table 2 shows the overall comorbidity rates separately for all ICD-10-GM chapters and odds ratios. Individuals with PTSD show, nearly overall, higher rates of comorbidities and odds ratios higher than one, especially for mental and behavioural disorders—83% are affected by another mental disorder than PTSD, twice as much as for the No-PTSD CG (41%), with an odds ratio of 7.1. The PTSD-group shows odds ratios above two for chapters VI, XIII, XVIII, XX, and XXII.

Table 2.

Comorbidities by ICD-10-GM chapters for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548)

| Chapter | ICD-10-GM | PTSD | No-PTSD CG | Odds ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Persons affected | (%) | Persons affected | (%) | ||

| I | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 6700 | (52.0) | 20,086 | (39.0) | 1.7 |

| II | Neoplasms | 4610 | (35.8) | 16,498 | (32.0) | 1.2 |

| III | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 1912 | (14.8) | 5604 | (10.9) | 1.4 |

| IV | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 7162 | (55.6) | 23,620 | (45.8) | 1.5 |

| V | Mental and behavioral disorders | 10,725 | (83.2) | 21,220 | (41.2) | 7.1 |

| VI | Diseases of the nervous system | 5784 | (44.9) | 12,735 | (24.7) | 2.5 |

| VII | Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 5278 | (41.0) | 18,168 | (35.2) | 1.3 |

| VIII | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | 3948 | (30.6) | 11,053 | (21.4) | 1.6 |

| IX | Diseases of the circulatory system | 6565 | (50.9) | 20,996 | (40.7) | 1.5 |

| X | Diseases of the respiratory system | 9829 | (76.3) | 33,585 | (65.2) | 1.7 |

| XI | Diseases of the digestive system | 6986 | (54.2) | 19,422 | (37.7) | 2.0 |

| XII | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 6289 | (48.8) | 20,830 | (40.4) | 1.4 |

| XIII | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 10,236 | (79.4) | 33,834 | (65.6) | 2.0 |

| XIV | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 8784 | (68.2) | 32,370 | (62.8) | 1.3 |

| XV | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | 818 | (6.3) | 3461 | (6.7) | 0.9 |

| XVI | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 54 | (0.4) | 292 | (0.6) | 0.7 |

| XVII | Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 2581 | (20.0) | 7847 | (15.2) | 1.4 |

| XVIII | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified | 9944 | (77.2) | 29,876 | (58.0) | 2.5 |

| XIX | Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 6974 | (54.1) | 19,579 | (38.0) | 1.9 |

| XX | External causes of morbidity and mortality | 247 | (1.9) | 295 | (0.6) | 3.4 |

| XXI | Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 11,007 | (85.4) | 41,094 | (79.7) | 1.5 |

| XXII | Key numbers for specific purposes | 121 | (0.9) | 151 | (0.3) | 3.2 |

Total health care costs

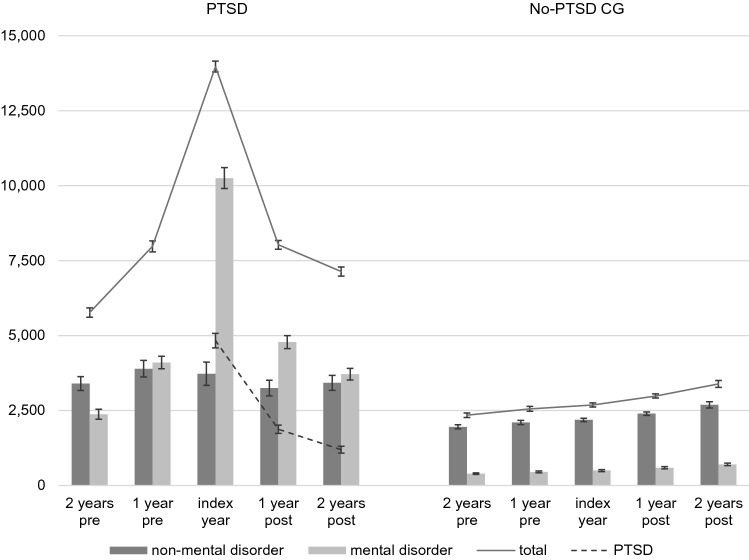

Table 3 shows the total direct and indirect health care costs that arise for both the PTSD and the No-PTSD CG for all analysed outcomes, respectively. In addition, Fig. 2 provides a graphical illustration of changes in total costs as well as in costs due to mental disorders, non-mental disorders and PTSD over the whole course of the analysis period for both groups. For the PTSD-group, costs show a steep upward trend from 2 years prior until the year of index diagnosis, and a corresponding downward trend until 2 years after the index year. Mean costs increase by 142% until the index year (2 years pre 5767 EUR, CI 5537–5996; index year 13,970 EUR, CI 13,585–14,356) and decrease until 2 years after by 49% (7133 EUR, CI 6882–7384). Two years afterwards, costs remain 24% higher than for 2 years preceding the index year. Mean costs 1 year prior (7974 EUR, CI 7696–8251) and 1 year after index year (8026 EUR, CI 7764–8289) are nearly equal. The same trend in mean costs can be seen for all respective outcome variables, except drug costs. Here, mean as well as median costs increase nearly continuously over the analysis period. For total and outpatient treatment costs, medians follow the same trend as the respective mean values; for inpatient treatments, sickness benefit payments, and losses of gross value, all yearly medians remain zero. Total costs for the PTSD-group account for 42,870 EUR (CI 41,909–43,831) over the whole analysis period.

Table 3.

Total costs resulting for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548)

| PTSD | No-PTSD CG | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | SD | CImean | Median | Mean | SD | CImean | p | d | CId | |

| Drug therapies | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 75 | 447 | 4069 | 377–518 | 31 | 267 | 5900 | 216–318 | 0.03 | 0.01–0.05 | |

| 1 year pre | 95 | 511 | 4217 | 439–584 | 32 | 290 | 6303 | 235–344 | * | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 |

| Index year | 129 | 640 | 4460 | 563–717 | 34 | 305 | 2933 | 279–330 | * | 0.10 | 0.08–0.12 |

| 1 year post | 116 | 689 | 5080 | 602–777 | 36 | 336 | 2279 | 317–356 | * | 0.12 | 0.10–0.14 |

| 2 years post | 113 | 724 | 5199 | 635–814 | 37 | 410 | 6026 | 358–462 | * | 0.05 | 0.03–0.07 |

| Total | 652 | 3013 | 21,324 | 2644–3381 | 219 | 1607 | 20,853 | 1427–1787 | * | 0.07 | 0.05–0.09 |

| Outpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 518 | 808 | 989 | 790–825 | 279 | 440 | 572 | 436–445 | * | 0.54 | 0.52–0.56 |

| 1 year pre | 673 | 994 | 1017 | 976–1011 | 298 | 471 | 618 | 466–476 | * | 0.73 | 0.71–0.75 |

| Index year | 1,311 | 1657 | 1349 | 1634–1680 | 311 | 495 | 651 | 489–500 | * | 1.39 | 1.37–1.41 |

| 1 year post | 989 | 1398 | 1370 | 1374–1422 | 329 | 524 | 688 | 519–530 | * | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| 2 years post | 842 | 1234 | 1286 | 1212–1256 | 348 | 558 | 756 | 551–564 | * | 0.76 | 0.74–0.78 |

| Total | 5123 | 6090 | 4272 | 6016–6164 | 1864 | 2489 | 2387 | 2468–2509 | * | 1.26 | 1.24–1.28 |

| Inpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 1292 | 6202 | 1185–1399 | 0 | 381 | 1959 | 364–398 | * | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 1783 | 6245 | 1675–1891 | 0 | 433 | 2752 | 409–456 | * | 0.36 | 0.34–0.38 |

| Index year | 0 | 3376 | 8001 | 3238–3515 | 0 | 445 | 3305 | 417–474 | * | 0.63 | 0.61–0.65 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 1749 | 5817 | 1649–1850 | 0 | 527 | 2948 | 501–552 | * | 0.33 | 0.31–0.35 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 1589 | 5606 | 1492–1686 | 0 | 563 | 5358 | 517–609 | * | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 |

| Total | 3275 | 9790 | 19,530 | 9453–10,127 | 0 | 2349 | 9485 | 2267–2431 | * | 0.61 | 0.59–0.63 |

| Sickness benefit payments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 265 | 1581 | 238–292 | 0 | 73 | 776 | 67–80 | * | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 471 | 2168 | 433–508 | 0 | 81 | 838 | 74–89 | * | 0.32 | 0.30–0.34 |

| Index year | 0 | 1163 | 3584 | 1101–1225 | 0 | 93 | 899 | 85–100 | * | 0.60 | 0.58–0.62 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 451 | 2066 | 415–486 | 0 | 112 | 1076 | 103–121 | * | 0.25 | 0.24–0.27 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 331 | 1933 | 297–364 | 0 | 132 | 1154 | 122–142 | * | 0.15 | 0.13–0.17 |

| Total | 0 | 2681 | 6769 | 2564–2797 | 0 | 492 | 2735 | 468–515 | * | 0.56 | 0.54–0.58 |

| Losses of gross value | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 2955 | 8314 | 2812–3099 | 0 | 1180 | 4237 | 1143–1216 | * | 0.33 | 0.32–0.35 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 4215 | 10,692 | 4030–4399 | 0 | 1278 | 4456 | 1239–1316 | * | 0.47 | 0.45–0.49 |

| Index year | 0 | 7133 | 15,250 | 6870–7397 | 0 | 1346 | 4656 | 1306–1386 | * | 0.72 | 0.70–0.74 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 3739 | 9979 | 3567–3911 | 0 | 1482 | 5093 | 1438–1526 | * | 0.35 | 0.34–0.37 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 3255 | 9212 | 3096–3414 | 0 | 1721 | 5768 | 1671–1771 | * | 0.23 | 0.21–0.25 |

| Total | 579 | 21,297 | 36,432 | 20,668–21,926 | 165 | 7006 | 16,320 | 6865–7147 | * | 0.65 | 0.63–0.67 |

| Total costs | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 1626 | 5767 | 13,279 | 5537–5996 | 571 | 2341 | 8602 | 2267–2416 | * | 0.35 | 0.33–0.37 |

| 1 year pre | 2346 | 7974 | 16,070 | 7696–8251 | 617 | 2552 | 9209 | 2473–2632 | * | 0.50 | 0.48–0.52 |

| Index year | 4501 | 13,970 | 22,332 | 13,585–14,356 | 650 | 2683 | 7868 | 2615–2751 | * | 0.92 | 0.90–0.94 |

| 1 year post | 2861 | 8026 | 15,208 | 7764–8289 | 706 | 2982 | 8015 | 2912–3051 | * | 0.51 | 0.49–0.53 |

| 2 years post | 2489 | 7133 | 14,539 | 6882–7384 | 764 | 3384 | 13,193 | 3270–3498 | * | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

| Total | 20,801 | 42,870 | 55,654 | 41,909–43,831 | 5,928 | 13,942 | 34,871 | 13,641–14,243 | * | 0.73 | 0.71–0.75 |

Costs are expressed in euros (EUR)

CI 95% confidence intervals

*Significant test results for Student’s t test after Bonferroni-correction (p < 0.001/36 = 0.000027)

Fig. 2.

Graphical illustration of changes in total, mental disorder-, non-mental disorder-, and PTSD-specific costs over time for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548). Error bars display 95% confidence intervals (CI). Costs are expressed in euros (EUR)

In contrast, the No-PTSD CG shows a continuous slight upward trend in costs over the course of the study period. Mean costs increase constantly and in every analysed outcome variable for each of the subsequent years. For mean total costs, an increased rate of 45% can be estimated from 2 years prior to 2 years after the index year (2 years pre: 2341 EUR, CI 2267–2416; 2 years post: 3384 EUR, CI 3270–3498). Median costs for drug therapies, outpatient treatments, and total costs follow the same trend; medians for the other outcome variables remain zero for all years. In total, the No-PTSD CG causes costs of 13,942 EUR (CI 13,641–14,243) per individual over the entire observation period.

Comparisons between groups show significant differences after Bonferroni correction for nearly all outcomes and years. In total, costs for individuals with PTSD are more than three times higher over the total 5-year period compared to those for the No-PTSD CG. A Cohen’s d of 0.73 (CI 0.71–0.75) shows an upper mediate effect size. Differences are highest in the index year where the PTSD-group incurs costs five times higher than the No-PTSD CG (means 13,970 EUR, CI 13,585–14,356 versus 2683 EUR, CI 2615–2751), with a large effect size of 0.92 (CI 0.90–0.94). For the years preceding and following the index year, costs are consistently more than twice as high for individuals with PTSD in relation to the non-exposed controls (means 5767–8026 EUR versus 2341–3384 EUR), with small effect sizes for the 2 years preceding (d = 0.35; CI 0.33–0.37) as well as the 2 years following (d = 0.28; CI 0.26–0.30), and medium effect sizes for 1 year preceding (d = 0.50; CI 0.48–0.52) and following (d = 0.51; CI 0.49–0.53) the index year. The same results can be seen for all respective outcomes, with the largest effect sizes for outpatient treatments. Only drug therapies show not even small effect sizes, such that differences here can be gauged as very small.

Health care costs due to mental disorders

Table 4 displays the results for the analysis of costs that lead back to mental disorders only. For the PTSD-group, mental disorder-specific costs show the same trend as total costs, only with higher increase and decrease rates. Mean costs rise by 332% from 2 years preceding (2374 EUR, CI 2208–2540) until the index year (10,251 EUR, CI 9905–10,597) and decrease by 64% until 2 years after the index year (3709 EUR, CI 3517–3901). Costs remain 56% higher 2 years after compared to 2 years preceding the index year. All outcome variables follow the same trend. The highest increase rate occurs in sickness benefit payments; from 2 years prior until the index year, costs increase by 567% (mean pre 144 EUR, CI 123–164; index year: 960 EUR, CI 903–1017). Proportionally to total costs, mental disorder-specific total costs (mean 25,215 EUR, CI 24,501–25,929) account for 59%.

Table 4.

Mental disorder-specific costs for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548)

| PTSD | No-PTSD CG | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | SD | CImean | Median | Mean | SD | CImean | p | d | CId | |

| Drug therapies | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 57 | 243 | 53–62 | 0 | 9 | 86 | 9–10 | * | 0.36 | 0.34–0.38 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 71 | 244 | 67–75 | 0 | 10 | 82 | 9–10 | * | 0.47 | 0.45–0.49 |

| Index year | 10 | 119 | 315 | 114–125 | 0 | 10 | 82 | 9–11 | * | 0.69 | 0.67–0.71 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 105 | 309 | 100–110 | 0 | 10 | 79 | 10–11 | * | 0.61 | 0.59–0.63 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 95 | 279 | 90–100 | 0 | 11 | 78 | 10–11 | * | 0.59 | 0.57–0.61 |

| Total | 51 | 447 | 1154 | 427–467 | 0 | 50 | 348 | 47–53 | * | 0.66 | 0.64–0.68 |

| Outpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 97 | 354 | 751 | 341–367 | 0 | 91 | 321 | 89–94 | * | 0.59 | 0.57–0.61 |

| 1 year pre | 205 | 501 | 790 | 487–515 | 0 | 101 | 348 | 98–104 | * | 0.85 | 0.83–0.87 |

| Index year | 767 | 1164 | 1115 | 1145–1184 | 0 | 109 | 367 | 106–112 | * | 1.77 | 1.75–1.79 |

| 1 year post | 449 | 912 | 1179 | 892–932 | 0 | 117 | 377 | 114–120 | * | 1.27 | 1.25–1.29 |

| 2 years post | 335 | 739 | 1074 | 720–757 | 0 | 128 | 408 | 124–131 | * | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 |

| Total | 2682 | 3670 | 3522 | 3609–3730 | 67 | 546 | 1382 | 534–558 | * | 1.56 | 1.54–1.58 |

| Inpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 655 | 5504 | 560–750 | 0 | 55 | 853 | 47–62 | * | 0.23 | 0.21–0.25 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 983 | 4353 | 908–1058 | 0 | 76 | 1537 | 63–89 | * | 0.38 | 0.36–0.40 |

| Index year | 0 | 2727 | 7282 | 2601–2853 | 0 | 78 | 1016 | 69–87 | * | 0.78 | 0.76–0.80 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 1188 | 5193 | 1098–1278 | 0 | 109 | 1780 | 93–124 | * | 0.38 | 0.37–0.40 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 1009 | 4860 | 925–1093 | 0 | 114 | 1,635 | 100–128 | * | 0.34 | 0.32–0.36 |

| Total | 0 | 6562 | 16,712 | 6274–6851 | 0 | 431 | 3737 | 399–463 | * | 0.75 | 0.73–0.77 |

| Sickness benefit payments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 144 | 1188 | 123–164 | 0 | 26 | 494 | 22–31 | * | 0.17 | 0.15–0.19 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 311 | 1774 | 280–341 | 0 | 30 | 546 | 25–35 | * | 0.30 | 0.28–0.32 |

| Index year | 0 | 960 | 3297 | 903–1017 | 0 | 34 | 590 | 29–39 | * | 0.59 | 0.57–0.61 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 355 | 1850 | 323–387 | 0 | 45 | 770 | 38–52 | * | 0.29 | 0.27–0.31 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 242 | 1706 | 213–272 | 0 | 54 | 781 | 48–61 | * | 0.18 | 0.16–0.20 |

| Total | 0 | 2011 | 5796 | 1911–2111 | 0 | 190 | 1773 | 175–206 | * | 0.60 | 0.58–0.62 |

| Losses of gross value | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 1165 | 5988 | 1062–1268 | 0 | 210 | 2326 | 190–230 | * | 0.28 | 0.26–0.30 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 2233 | 8627 | 2084–2382 | 0 | 234 | 2494 | 213–256 | * | 0.45 | 0.43–0.47 |

| Index year | 0 | 5281 | 14,021 | 5039–5523 | 0 | 265 | 2736 | 242–289 | * | 0.75 | 0.73–0.77 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 2222 | 8703 | 2071–2372 | 0 | 306 | 3068 | 279–332 | * | 0.40 | 0.38–0.42 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 1624 | 7531 | 1494–1754 | 0 | 392 | 3497 | 361–422 | * | 0.27 | 0.25–0.29 |

| Total | 0 | 12,524 | 28,597 | 12,031–13,018 | 0 | 1,407 | 8479 | 1334–1480 | * | 0.75 | 0.73–0.77 |

| Total costs | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 127 | 2374 | 9620 | 2208–2540 | 0 | 392 | 3119 | 365–419 | * | 0.39 | 0.37–0.41 |

| 1 year pre | 317 | 4099 | 12,064 | 3890–4307 | 0 | 451 | 3577 | 420–481 | * | 0.58 | 0.56–0.60 |

| Index year | 2029 | 10,251 | 20,057 | 9905–10,597 | 0 | 496 | 3722 | 464–528 | * | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 |

| 1 year post | 760 | 4782 | 12,502 | 4566–4998 | 0 | 587 | 4447 | 549–625 | * | 0.61 | 0.59–0.63 |

| 2 years post | 509 | 3709 | 11,105 | 3517–3901 | 0 | 698 | 4850 | 657–740 | * | 0.46 | 0.44–0.48 |

| Total | 7505 | 25,215 | 41,341 | 24,501–25,929 | 82 | 2624 | 11,916 | 2521–2727 | * | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 |

Costs are expressed in euros (EUR)

CI 95% confidence intervals

*Significant test results for Student’s t test after Bonferroni-correction (p < 0.001/36 = 0.000027)

The same trend as for total costs can also be seen for the No-PTSD CG. In all outcome variables, costs increase constantly in every year. Total costs due to mental disorders increase by 78% from 2 years preceding (mean 392 EUR, CI 365–419) until 2 years after the index year (mean 698 EUR, CI 657–740). Average mental disorder-specific costs of 2624 EUR (CI 2521–2727) in total per individual account for 19% of all occurring health care costs which accumulated over the whole analysis period.

All t tests that were conducted between the PTSD and the No-PTSD CG show significant results. Compared to total costs, differences show even higher discrepancies for mental disorder-specific health care costs. In total, the PTSD-group causes costs 9.6 times higher as compared to the No-PTSD CG, with a large effect size (d = 1.06; CI 1.04–1.08). In the year of index diagnosis, costs due to mental disorders are 20.7 times higher in the PTSD-group (means 10,251 EUR, CI 9905–10,597 versus 496 EUR, CI 464–528), with a large effect size of d = 1.02 (CI 1.00–1.04). For all other analysed periods, yearly total costs are between five to nine times higher in the PTSD-group (means 2374–4782 EUR versus 392–698 EUR), with small to medium effect sizes (d = 0.39–0.61). The same findings can be seen for all respective outcome variables, with the largest effect sizes for outpatient treatments (d = 0.59–1.77).

Health care costs not due to mental disorders

In Table 5, results for analyses of costs not due to mental disorders are shown. In contrast to trends for total and mental disorder-specific analyses, results in the PTSD-group show different trends for non-mental disorder costs. Total health care costs remain stable from 2 years preceding (mean 3396 EUR, CI 3243–3550) until 2 years after the index year (3419 EUR, CI 3265–3573). Total health care costs show their maximum at 1 year preceding the index year (mean 3892 EUR, CI 3706–4078) and decrease slightly in the year of index diagnosis (mean 3725 EUR, CI 3543–3907), which is 10% higher compared to 2 years prior. Trends for outcome variables differ slightly: costs for drug therapies increase constantly every year, in total by 61% (mean 2 years pre 390 EUR, CI 320–460; 2 years post 629 EUR, CI 540–719). Costs for outpatient treatments increase as well, but only by 9% over the whole period (mean 2 years pre 454 EUR, CI 443–464; 2 years post: 495 EUR, CI 484–506). For inpatient treatments, sickness benefit payments, and losses of gross value, costs not due to mental disorders two years after the index year are lower compared to 2 years prior (decrease rates: 10%, 36%, 10%). Most confidence intervals for mean costs show overlaps in each respective outcome variable. Total health care costs not due to mental disorders of 17,677 EUR (CI 17,087–18,267) on average account for 41% of total health care costs in the PTSD-group.

Table 5.

Non-mental disorder-specific costs for the PTSD (N = 12,887) and the No-PTSD CG (N = 51,548)

| PTSD | No-PTSD CG | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | SD | CImean | Median | Mean | SD | CImean | p | d | CId | |

| Drug therapies | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 56 | 390 | 4057 | 320–460 | 29 | 257 | 5898 | 207–308 | 0.02 | 0.00–0.04 | |

| 1 year pre | 65 | 441 | 4204 | 368–513 | 30 | 280 | 6301 | 226–334 | 0.03 | 0.01–0.05 | |

| Index year | 70 | 521 | 4441 | 444–598 | 32 | 295 | 2929 | 269–320 | * | 0.07 | 0.05–0.09 |

| 1 year post | 72 | 584 | 5063 | 497–672 | 33 | 326 | 2275 | 306–346 | * | 0.09 | 0.07–0.10 |

| 2 years post | 72 | 629 | 5181 | 540–719 | 34 | 399 | 6025 | 347–451 | * | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 |

| Total | 405 | 2565 | 21,255 | 2198–2932 | 205 | 1557 | 20,843 | 1377–1737 | * | 0.05 | 0.03–0.07 |

| Outpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 302 | 454 | 603 | 443–464 | 231 | 349 | 445 | 345–353 | * | 0.22 | 0.20–0.24 |

| 1 year pre | 332 | 493 | 604 | 482–503 | 246 | 370 | 482 | 366–374 | * | 0.24 | 0.22–0.26 |

| Index year | 310 | 493 | 717 | 480–505 | 254 | 386 | 508 | 382–390 | * | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 |

| 1 year post | 307 | 486 | 640 | 475–497 | 266 | 407 | 542 | 403–412 | * | 0.14 | 0.12–0.16 |

| 2 years post | 317 | 495 | 641 | 484–506 | 279 | 430 | 600 | 425–435 | * | 0.11 | 0.09–0.13 |

| Total | 1876 | 2421 | 2107 | 2384–2457 | 1533 | 1942 | 1762 | 1927–1958 | * | 0.26 | 0.24–0.28 |

| Inpatient treatments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 637 | 2650 | 591–682 | 0 | 326 | 1682 | 312–341 | * | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 804 | 4530 | 726–882 | 0 | 357 | 2042 | 339–374 | * | 0.16 | 0.15–0.18 |

| Index year | 0 | 648 | 3018 | 596–700 | 0 | 367 | 3076 | 341–394 | * | 0.09 | 0.07–0.11 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 560 | 2215 | 521–598 | 0 | 418 | 2192 | 399–437 | * | 0.06 | 0.05–0.08 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 579 | 2347 | 539–620 | 0 | 450 | 5009 | 406–493 | * | 0.03 | 0.01–0.05 |

| Total | 295 | 3227 | 8156 | 3087–3368 | 0 | 1918 | 7910 | 1849–1986 | * | 0.17 | 0.15–0.18 |

| Sickness benefit payments | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 121 | 1054 | 103–140 | 0 | 47 | 599 | 42–52 | * | 0.10 | 0.09–0.12 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 162 | 1279 | 140–184 | 0 | 51 | 634 | 46–57 | * | 0.14 | 0.12–0.16 |

| Index year | 0 | 205 | 1522 | 178–231 | 0 | 58 | 676 | 52–64 | * | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 96 | 937 | 80–112 | 0 | 67 | 754 | 60–73 | 0.04 | 0.02–0.06 | |

| 2 years post | 0 | 89 | 915 | 73–104 | 0 | 78 | 848 | 71–85 | 0.01 | − 0.01 to 0.03 | |

| Total | 0 | 672 | 3262 | 616–729 | 0 | 301 | 1995 | 284–319 | * | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 |

| Losses of gross value | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 0 | 1794 | 5742 | 1695–1893 | 0 | 971 | 3489 | 941–1001 | * | 0.20 | 0.18–0.22 |

| 1 year pre | 0 | 1993 | 6424 | 1882–2104 | 0 | 1043 | 3635 | 1011–1074 | * | 0.22 | 0.20–0.24 |

| Index year | 0 | 1858 | 6636 | 1744–1973 | 0 | 1080 | 3691 | 1048–1111 | * | 0.18 | 0.16–0.20 |

| 1 year post | 0 | 1520 | 4814 | 1437–1603 | 0 | 1176 | 4008 | 1142–1211 | * | 0.08 | 0.06–0.10 |

| 2 years post | 0 | 1626 | 5115 | 1538–1714 | 0 | 1329 | 4506 | 1290–1368 | * | 0.06 | 0.05–0.08 |

| Total | 0 | 8792 | 18,815 | 8467–9116 | 0 | 5599 | 12,841 | 5488–5709 | * | 0.22 | 0.21–0.24 |

| Total costs | |||||||||||

| 2 years pre | 851 | 3396 | 8913 | 3243–3550 | 478 | 1951 | 7915 | 1883–2019 | * | 0.18 | 0.16–0.20 |

| 1 year pre | 954 | 3892 | 10,774 | 3706–4078 | 507 | 2101 | 8265 | 2030–2172 | * | 0.20 | 0.18–0.22 |

| Index year | 849 | 3725 | 10,540 | 3543–3907 | 534 | 2186 | 6726 | 2127–2244 | * | 0.20 | 0.18–0.22 |

| 1 year post | 923 | 3245 | 8450 | 3100–3391 | 568 | 2394 | 6390 | 2339–2450 | * | 0.12 | 0.11–0.14 |

| 2 years post | 954 | 3419 | 8918 | 3265–3573 | 617 | 2685 | 12,067 | 2581–2790 | * | 0.06 | 0.04–0.08 |

| Total | 7894 | 17,677 | 34,196 | 17,087–18,267 | 5024 | 11,317 | 31,521 | 11,045–11,590 | * | 0.20 | 0.18–0.22 |

Costs are expressed in euros (EUR)

CI 95% confidence intervals

*Significant test results for Student’s t test after Bonferroni-correction (p < 0.001/36 = 0.000027)

Again, the same trends can be seen in all outcome variables for the No-PTSD CG with respect to total and mental disorder-specific costs. Mean costs increase constantly in every year, in total by 38%, from 1951 EUR (CI 1883–2019) 2 years prior to 2685 EUR (CI 2581–2790) 2 years after the index year. In total, mean costs not due to mental disorders accumulate to 11,317 EUR (CI 11,045–11,590), which accounts for 81% of total health care costs over the whole analysis period.

Comparisons between groups show significant differences for nearly all outcomes and periods and the PTSD-group causes higher costs for every year as well. In any event, differences are far lower compared to total and mental disorder-specific costs. Ratios for total costs range only from 1.3 to 1.9 per year, and with very up to slightly small effect sizes (d = 0.06–0.26). In total, the PTSD-group incurs non-mental disorder-specific costs that are 1.6 times higher.

Health care costs due to PTSD

For broader clarity in estimating costs that arise due to PTSD, Table 6 displays the expenses that are caused specifically by PTSD after index diagnosis in the PTSD-group as well as the number of patients treated. Costs are highest in the index year for all outcome variables and consistently decrease in both the following years. One year after the index year, PTSD-specific total costs decrease by 61% (4830 EUR, CI 4590–5070 versus 1873 EUR, CI 1734–2012); another year later, costs reduce again by 36% (1192 EUR, CI 1077–1307). In total, PTSD-specific costs decrease by 75%. Reduction rates for single outcome variables range from 56 to 80%. The amount for the entire period (mean 7895 EUR, CI 7523–8266) accounts for 18% of the total direct and indirect costs for individuals with PTSD (mean 42,870 EUR), proportionally in the year of index diagnosis for 35% (4830 EUR of 13,970 EUR). In the index year, all individuals with PTSD utilise PTSD-specific health care services; 1 year after, only 7110 (55%) do so, and 2 years later only 5827 (45%). The same trends can be observed for all respective outcomes.

Table 6.

PTSD-specific costs for the PTSD-group (N = 12,887)

| Patients treated | (%) | Median | Mean | SD | CImean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient treatments | ||||||

| Index year | 12,116 | (94.0) | 252 | 603 | 838 | 588–617 |

| 1 year post | 6971 | (54.0) | 59 | 385 | 797 | 371–398 |

| 2 years post | 5730 | (44.5) | 0 | 266 | 627 | 255–276 |

| Total | 12,245 | (95.0) | 498 | 1253 | 1901 | 1220–1286 |

| Inpatient treatments | ||||||

| Index year | 2043 | (15.8) | 0 | 1627 | 5728 | 1529–1726 |

| 1 year post | 529 | (4.1) | 0 | 426 | 2938 | 375–477 |

| 2 years post | 436 | (3.4) | 0 | 330 | 2822 | 281–379 |

| Total | 2387 | (18.5) | 0 | 2384 | 8442 | 2238–2529 |

| Sickness benefit payments | ||||||

| Index year | 696 | (5.4) | 0 | 405 | 2253 | 366–444 |

| 1 year post | 362 | (2.8) | 0 | 156 | 1236 | 135–177 |

| 2 years post | 157 | (1.2) | 0 | 78 | 972 | 62–95 |

| Total | 878 | (6.8) | 0 | 639 | 3250 | 583–695 |

| Losses of gross value | ||||||

| Index year | 1280 | (9.9) | 0 | 2195 | 9608 | 2029–2361 |

| 1 year post | 579 | (4.5) | 0 | 906 | 5781 | 806–1006 |

| 2 years post | 350 | (2.7) | 0 | 518 | 4627 | 438–598 |

| Total | 1601 | (12.4) | 0 | 3619 | 15,139 | 3357–3880 |

| Total costs | ||||||

| Index year | 12,887 | (100.0) | 425 | 4830 | 13,917 | 4590–5070 |

| 1 year post | 7110 | (55.2) | 70 | 1873 | 8035 | 1734–2012 |

| 2 years post | 5827 | (45.2) | 0 | 1192 | 6665 | 1077–1307 |

| Total | 12,887 | (100.0) | 944 | 7895 | 21,516 | 7523–8266 |

Costs are expressed in euros (EUR)

CI 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Interpretation of results

In this study, we compared changes in health care costs over time and determined estimates for incremental costs that arise for individuals with an incident diagnosis of PTSD, in relation to an age and gender-adjusted control group of non-exposed individuals. The findings suggest that overall health care costs for individuals with PTSD were more than three times higher compared to non-exposed controls in a 5-year period (42,870 EUR versus 13,942 EUR). Costs for the PTSD-group are at least twice as high in every year preceding and following index diagnosis. Hence, individuals with PTSD seem to suffer from more complex disorder conditions and more severe preceding and continuing overall health impairments.

Most of these impairments and incremental costs seem to be caused by PTSD itself and co-occurring mental disorders. This is supported by the analyses on costs and cost developments as well as by the results for co-occurring disorders. CCIs are slightly higher and co-occurrence rates are nearly overall increased in the PTSD-group but are the highest by far for mental and behavioural disorders, with an odds ratio of 7.1. In terms of costs, mental disorder-specific health care costs account for 59% of overall costs in the PTSD-group, but only for 19% in the No-PTSD CG. In the No-PTSD CG, costs increase constantly year by year at a small rate, which can be explained by overall increases in health care expenditures within the German statutory health care system [32]. Absolute mean costs for non-mental disorder-specific utilisations are roughly 60% higher in total in the PTSD-group but remain nearly stable over the whole analysis period. In contrast, total costs and costs due to mental disorders arise drastically in the index year of a PTSD diagnosis but return to their initial level afterwards.

Overall, individuals with PTSD cause around 29,000 EUR more in costs over a 5-year period compared to non-exposed average insurants. Of these, incremental costs specifically due to PTSD only can be estimated at roughly 8000 EUR, equal to 27% of total incremental costs; 73% of these costs seem to be due to other disorders, mainly other mental disorders. However, total costs show a proportionally lower increase rate from 2 years preceding the index year until 2 years after for individuals with PTSD compared to the No-PTSD CG (23% versus 45%). Taking these trends into account, we could assume that treatments covered in the statutory health care system lead to a decline of symptom severity and could counterbalance an outbreak of PTSD in the long run. International guidelines highly recommend psychotherapy with additional pharmacotherapy if necessary as the treatment option of choice for PTSD [33, 34] and empirical evidence supports their effectiveness [35]. 94% of individuals with PTSD utilised PTSD-specific outpatient services in the year after index diagnosis. Despite no clear conclusions on these terms can be drawn, the results let assume that focussing treatments for mental health impairments, e.g. psychotherapies or pharmacotherapies, are beneficial for individuals with PTSD and early preventive approaches could prevent high incremental costs.

Previous research on costs due to mental disorders shows different results, along with a lack of standardised procedures. Due to different methodological approaches, comparability with other research on costs stemming from PTSD and other mental disorders is restricted. Compared to one US-American study on Medicaid and private insurance data, our results correspond with the findings. The study estimated direct costs due to PTSD at 10,960–18,753 USD per patient per year [23], which is comparable to the reported direct and indirect costs of 13,970 EUR in the year of index diagnosis found in this study. In contrast, a Northern Ireland study estimated annual costs of 4236 EUR for individuals with 12-month prevalent PTSD [24], which is remarkably lower. Compared to research on costs due to other mental disorders, our results seem to be in an expected range. Research for borderline personality disorders (BPD, ICD-10-GM F60.3) estimated yearly costs of 16,852 EUR per affected individual [36], which is comparable to our findings. A systematic review on costs due to eating disorders reported annual costs per patient of 1288–8042 USD [17], which again is lower than our findings. A similar cost-analysis on claims data with comparable estimation approaches found costs of 8290 EUR for an incident BPD and 3616 EUR for an incident major depressive disorder (ICD-10-GM F32 and F33) in the year of index diagnosis [37].

Compared to these findings, costs due to PTSD turn out to be higher than for other mental disorders. Considering the complexity and severity of PTSD and high co-occurrence rates for mental and physical disorders, high costs for PTSD seem reasonable. Due to the large sample size and conservative estimation approaches, our results can be considered good estimates for costs due to PTSD. Moreover, this study describes cost developments over a long analysis period preceding and following incident PTSD. In addition, the results add evidence as to the high financial and economic burden that PTSD causes for a welfare state, along with the immersive health restrictions for affected individuals.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered for this study. First, studies on claims data are generally associated with restrictions in data quality compared to the quality of primary data. Especially relevant for this study is the fact that no statements on the validity of diagnoses can be made. We tried to face these issues by defining strict inclusion and exclusion criteria; e.g., only secure diagnoses by inpatient services, or two or more outpatient diagnoses or one by a mental disorder specialist. Furthermore, due to data constraints, we could only include part of the cost factors that might be relevant. Because information is only available from the perspective of health insurers, data for other direct and indirect expenses—e.g., out-of-pocket expenses, early retirements, life quality, and thus, quality-adjusted life years—as well as reliable information on disease remissions for assessing whether or not treatments were successful could not be included. Additionally, data for short-term incapacities to work are probably not covered by claims data [29] so that results for this outcome are probably underestimated. Due to insufficient data on diagnosis-specific medications, drug-therapy costs could not be included in the analysis of costs due to PTSD-specific services. Thus, expressed costs are only estimates, and real occurring costs in total as well as PTSD-specific costs are probably even higher. At any rate, the overall quality of German claims data can be rated as good [38] and, considering the available data sources and the sample sizes, our findings should suffice as good estimates. As only scant information on the amount of incremental costs due to PTSD is available, our study contributes to research on this disease and on mental disorders overall.

Differences in sociodemographic data could also restrict comparability between groups; one could also argue that we should have expanded our matching procedure to characteristics beyond gender and age, or applied Propensity Score Matchings [39]. Considering the explorative approach of this study and the aim of identifying estimates for incremental costs due to PTSD compared to non-diseased average insurants, we consciously refrained from using broader approaches. Controlling only by gender and age enables comparisons between individuals who suffer from PTSD and non-exposed average controls so that conclusions about the overall health status and costs arising from PTSD in relation to average insurants can be drawn. Furthermore, the chosen procedure enables estimations of costs due to symptoms and co-occurring disorders before an index diagnosis of PTSD; controlling for, e.g., CCIs or co-occurrence rates would have inhibited this.

Conclusions

This study provides estimates for incremental costs due to incident PTSD and describes trends of cost developments arising for the health care system and welfare state over a 5-year period. Individuals with PTSD cause costs of approximately 43,000 EUR in total, three times higher than for non-exposed average insurants. All in all, incremental costs can be estimated at roughly 29,000 EUR and lead back mostly to PTSD and to other co-occurring mental and behavioural disorders. Furthermore, the findings support evidence on the complexity and severity of health restrictions caused by PTSD due to co-occurring disorders, especially accompanying mental disorders, which account for double the costs in relation to PTSD-specific costs only. Taking the overall reduction rates in cost developments after an onset of PTSD into account, this study suggests that treatments for PTSD are efficacious and benefit affected individuals. Thus, health policies should focus overall on enhancing and encouraging early evidence-based treatments and prevention approaches. Further research should investigate precise cost–benefit estimates for treatment approaches for PTSD and other mental disorders in general on claims data.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christoph Kröger and Jochen Walker contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jönsson B, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, McLaughlin KA. Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: prevalence, correlates and consequences. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2015;28(4):307–311. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017;8:1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradus JL. Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017;9:251–260. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S106250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol. Med. 1991;21(3):713–721. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700022352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunello N, Davidson JRT, Deahl M, Kessler RC, Mendlewicz J, Racagni G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: diagnosis and epidemiology, comorbidity and social consequences, biology and treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;43(3):150–162. doi: 10.1159/000054884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott KM, Koenen KC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, et al. Associations between lifetime traumatic events and subsequent chronic physical conditions: a cross-national, cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob L, Haro JM, Koyanagi A. Post-traumatic stress symptoms are associated with physical multimorbidity: findings from the adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2007. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;232:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1032(1):141–153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spitzer C, Barnow S, Volzke H, John U, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and physical illness: findings from the general population. Psychosomat. Med. 2009;71(9):1012–1017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc76b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradus JL, Farkas DK, Svensson E, Ehrenstein V, Lash TL, Milstein A, et al. Associations between stress disorders and cardiovascular disease events in the Danish population. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009334. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Üstün TB, et al. Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1234–1246. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2009;18(1):23–33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layard R, Clark DM, Knapp M, Mayraz G. Cost-benefit analysis of psychological therapy. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2007;202(1):90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bode K, Götz-von-Olenhusen NM, Wunsch E-M, Kliem S, Kröger C. Population-based cost-offset analyses for disorder-specific treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in Germany. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017;50(3):239–249. doi: 10.1002/eat.22686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuhldreher N, Konnopka A, Wild B, Herzog W, Zipfel S, Löwe B, et al. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: a systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012;45(4):476–491. doi: 10.1002/eat.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetzelaer P, Lokkerbo J, Arntz A, van Asselt T, Smit F, Evers S. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of specialized psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: a synthesis of the evidence. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2017;20(4):177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wetzelaer P, Lokkerbo J, Arntz A, van Asselt T, Evers S. Kosteneffectiviteit van psychotherapie voor persoonlijkheidsstoornissen; een systematisch literatuuronderzoek van economische evaluatiestudies [Cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders. A systematic review on economic evaluation studies] Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 2016;58(10):717–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alonso J, Codony M, Kovess V, Angermeyer MC, Katz SJ, Haro JM, et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;190(4):299–306. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: Second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Chen L, Duhig AM, Dayoub EJ, Kantor ES, et al. Cost of post-traumatic stress disorder vs major depressive disorder among patients covered by medicaid or private insurance. Am. J. Managed Care. 2011;17(8):e314–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferry FR, Brady SE, Bunting BP, Murphy SD, Bolton D, O’Neill SM. The economic burden of PTSD in Northern Ireland. J. Trauma. Stress. 2015;28(3):191–197. doi: 10.1002/jts.22008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersohn F, Walker J. Characteristics and external validity of the German health risk institute (HRI) database. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):106–109. doi: 10.1002/pds.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graubner B. ICD-10-GM 2012. Köln: Dtsch Ärzteverl; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swart E, Bitzer EM, Gothe H, Harling M, Hoffmann F, Horenkamp-Sonntag D, et al. STandardisierte BerichtsROutine für Sekundärdaten Analysen (STROSA) – ein konsentierter Berichtsstandard für Deutschland, Version 2 [A consensus German reporting standard for secondary data analyses, Version 2 (STROSA-Standardisierte BerichtsROutine für DekundärdatenAnalysen)] Gesundheitswesen. 2016;78:e145–160. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004;57(12):1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Volkswirtschaftliche Kosten durch Arbeitsunfähigkeit [Economic costs due to inability to work]. https://www.baua.de/DE/Themen/Arbeitswelt-und-Arbeitsschutz-im-Wandel/Arbeitsweltberichterstattung/Kosten-der-AU/Kosten-der-Arbeitsunfaehigkeit_node.html (2019). Accessed 27 Jun 2019

- 30.Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature. 2019;567:305–307. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cumming G. The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 2014;25(1):7–29. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GKV Spitzenverband: Kennzahlen der gesetzlichen Krankeversicherung [Key figures for statutory health insurance]. https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/grafiken/gkv_kennzahlen/kennzahlen_gkv_2018_q4/GKV_Kennzahlen_Booklet_Q4-2018_300dpi_2019-03-15.pdf (2019). Accessed 27 Jun 2019

- 33.Flatten G, Gast U, Hofmann A, Knaevelsrud C, Lampe A, Liebermann P, et al. S3-Leitlinie Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung (ICD-10: F43.1) [S3-Guideline Post-traumatic stress disorders (ICD-10: F43.1)] Trauma Gewalt. 2011;5(3):202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: NICE guideline NG116: Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116 (2018). Accessed 27 Jun 2019 [PubMed]

- 35.Lancaster CL, Teeters JB, Gros DF, Back SE. Posttraumatic stress disorder: overview of evidence-based assessment and treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2016;5(11):105. doi: 10.3390/jcm5110105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Asselt ADI, Dirksen CD, Arntz A, Severens JL. The cost of borderline personality disorders: Societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. Eur. Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bode K, Vogel R, Walker J, Kröger C. Health care costs of borderline personality disorder and matched controls with major depressive disorder: a comparative study based on anonymized claims data. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017;18(9):1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreyögg J, Stargardt T. Gesundheitsökonomische evaluation auf grundlage von GKV-routinedaten [Health economic evaluation based on administrative data from German health insurance] Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2012;55(5):668–676. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West SG, Cham H, Thoemmes F, Renneberg B, Schulze J, Weiler M. Propensity scores as a basis for equating groups: basic principles and application in clinical treatment outcome research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014;82(5):906–919. doi: 10.1037/a0036387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]