Abstract

In this article, we review the current state of the field of high resolution magic angle spinning magnetic resonance spectroscopy (HRMAS MRS)-based cancer metabolomics since the beginning of the field in 2004; discuss the concept of cancer metabolomic fields, where metabolomic profiles measured from histologically benign tissues reflect patient cancer status; and report our HRMAS MRS metabolomic results that characterize metabolomic fields in prostatectomy-removed cancerous prostates. Three-dimensional mapping of cancer lesions throughout each prostate enabled multiple benign tissue samples per organ to be classified based on distance to and extent of the closest cancer lesion as well as Gleason score (GS) of the entire prostate. Cross-validated PLS-DA separations were achieved between cancer and benign tissue, and between cancer tissue from prostates with high (≥4+3) and low (≤3+4) GS. Metabolomic field effects enabled histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer to distinguish the GS and extent of the cancer lesion itself. Benign samples close to either low GS cancer or extensive cancer lesions could be distinguished from those far from cancer. Furthermore, a successfully cross-validated multivariate model for three benign tissue groups of varying distances to cancer lesions within one prostate indicates the scale of prostate cancer metabolomic fields. While these findings could be potentially useful in the prostate cancer clinic at present for analysis of biopsy or surgical specimens to complement current diagnostics, the confirmation of metabolomic fields should encourage further examination of cancer fields and can also enhance understanding of the metabolomic characteristics of cancer in myriad organ systems. Our results together with the success of HRMAS MRS-based cancer metabolomics presented in our literature review demonstrate the potential of cancer metabolomics to provide supplementary information for cancer diagnosis, staging and patient prognostication.

Graphical Abstract

Building upon the concept of cancer metabolomic field effects, we report a semi-quantitative, three-dimensional method of mapping cancer lesions and HRMAS MRS-scanned samples which enabled the distance-dependent existence of metabolomic fields and particularities regarding pathological features of the closest cancer to be identified in prostates, using histologically benign tissue.

1. Introduction and Review

Cancer annually causes multi-million deaths globally and is the second leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseases1. While investigations of cancer genomics and proteomics have shown great potential to enhance the collective understanding of cancer and detection and treatment options, cancer metabolomics, which measures the output from these upstream processes in form of small molecules, presents direct signatures of biochemical activity and can be more closely associated with disease phenotypes2.

Metabolomics aims to investigate relationships between the ensemble of metabolic alterations and disease phenotypes by revealing metabolic differences measured among samples of different clinical and pathological status. The introduction of high-resolution magic angle spinning magnetic resonance spectroscopy (HRMAS MRS) in 19963 allowed for analysis of intact human tissue samples at high spectral resolution4–7, while preserving tissue histological structures. It inspired widespread studies of global metabolite profiling by showing that compared with single metabolites, metabolomics analyses could distinguish cancer from non-cancer tissue with improved accuracy. In an early work, Tate and colleagues showed that unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) could distinguish kidney cortical cancer tissue from normal, and supervised linear discriminant analysis (LDA) presented the possibility of distinguishing them with 100% accuracy8.

Considering the current state of HRMAS MRS-based metabolomics and our recent work to expand its utility in investigations of histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer, in this article, we will first review the field of HRMAS MRS-based metabolomic (meaning not purely single metabolite) investigations of human cancers conducted with multivariate analysis (along with or without univariate methods); and then demonstrate the utility of human prostate cancer metabolomics in characterization of the disease with analyses of multiple cancer and histologically benign intact tissues sampled throughout surgically removed prostates from prostate cancer patients.

1.1. The Current State of HRMAS MRS-based Human Cancer Metabolomics

Our review of the literature indicated that investigations of human cancer tissue with HRMAS MRS-based metabolomics have been conducted in many organ systems since 2004, including adrenal9–11, bone12, brain13–17, breast18–29, colorectal30–32, esophagus33, lung34, pancreas35, prostate36–41, rectum42, skin43, stomach44, thyroid45–47, etc. Selected papers with sample sizes ≥ 100 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Selected HRMAS MRS metabolomics studies within the past 10 years.

Reviewed reports both published within the last 10 years and with total sample sizes ≥ 100 are summarized. Control sample size of 0 indicates a study only compared tumor or disease sub-types. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; BBNs, Bayesian belief networks; OPLS-DA, orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis; PLS-DA, partial least squares-discriminant analysis; PNNs, probabilistic neural networks; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

| Sample size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Year | Organ | Primary findings | n (tumor or disease) | n (control) | Ref |

| Vandergrift et al. | 2018 | prostate | – Metabolic profiles of histologically benign prostate tissue from cancerous prostates: ○ Show elevated myo-inositol, an endogenous tumor suppressor and potential mechanistic therapy target, in patients with highly-aggressive cancer ○ Identify a patient sub-group with less aggressive prostate cancer to avoid overtreatment if analyzed at biopsy ○ Subdivide the clinicopathologically indivisible PGG2 group into two distinct Kaplan-Meier recurrence groups, thereby identifying patients more at-risk for recurrence |

27 | 338 | 41 |

| Battini et al. | 2017 | pancreas | – Validated OPLS-DA distinguished pancreatic parenchyma (PP) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA) (R2Y=0.82, Q2=0.69) ○ Increased myo-inositol and glycerol in PP ○ Increased glucose, ascorbate, ethanolamine, lactate, and taurine in PA ○Increased ethanolamine was correlated with worse survival in Kaplan-Meier analysis |

106 | 17 | 35 |

| Haukaas et al. | 2016 | breast | – Hierarchical cluster analysis (validated with PLS-DA (p<0.001)) of breast cancer tumors revealed three significantly different metabolic clusters ○ Mc1 had highest glycerophosphocholine and phosphocholine ○ Mc2 had highest glucose ○ Mc3 had highest lactate and alanine – Genetic and protein subtypes were also divided along cluster groupings |

228 | 0 | 18 |

| Hansen et al. | 2016 | prostate | – Validated PLS-DA analysis differentiated prostate samples with high likelihood of having the poor prognosis-related TMPRSS-ERG fusion gene (TMPRSS-ERGhigh) from those with low likelihood (TMPRSS-ERGlow) (p<0.001) ○ Increased choline-containing metabolites in TMPRSS-ERGhigh ○ Decreased citrate and polyamines in TMPRSS-ERGhigh – Metabolic alterations are more pronounced in TMPRSS-ERGhigh samples possible risk-stratification identifier |

95 | 34 | 36 |

| Tian et al. | 2016 | colorectal | – Validated OPLS-DA distinguished colorectal cancer (CRC) samples from adjacent non-involved tissue (R2X=0.37, Q2=0.64) and low-grade and high-grade tumors (R2X=0.36, Q2=0.44) ○ Increased lactate, choline, phosphorylcholine, glycerophosphocholine, phosphoethanolamine, scyllo-inositol, glutathione, taurine, uracil, and cytosine in CRC ○ ROC model with these metabolites showed AUC = 0.965 for predicting CRC vs. non-tumor ○ ROC model for predicting low-grade vs. high-grade showed AUC = 0.904 –Stage I CRC samples were the most differentiated from their matched adjacent non-involved tissue samples |

50 | 50 | 30 |

| Jimenez et al. | 2013 | colorectal | – Validated OPLS-DA distinguished colorectal cancer (CRC) samples from adjacent mucosa (R2X=0.72, Q2=0.45) ○ Increased taurine, isoglutamine, choline, lactate, phenylalanine, tyrosine in CRC ○ Decreased lipids and triglycerides in CRC – Evidence of metabolic field effects ○ Tumor-adjacent mucosa (10 cm from tumor margin) has unique metabolic field changes that distinguish tumors by T- and N-stage more accurately than tumor tissue itself. |

83 | 87 | 31 |

| Bathen et al. | 2013 | breast | – Doubled cross-validated PLS-DA discriminated breast tumor tissue from adjacent benign with sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 93%, respectively ○ Increased choline-containing metabolites for tumor –These findings could allow on-line analysis of resection margins during breast cancer surgery |

263 | 65 | 22 |

| Giskeodagard et al. | 2013 | prostate | – PLS-DA ○ Separated cancer tissue from normal with sensitivity 86.9% and specificity 85.2% ○ Achieved correct classifications of 85.8%,77.4%, and 65.8% for GS≥7, GS = 6, and normal tissue – Decreased spermine and citrate in low grade prostate cancer tissue –Increased levels of the clinically-applied measure (total choline+creatine+polyamines)/citrate ratio in cancer |

111 | 47 | 24 |

| Miccoli et al. | 2012 | thyroid | – OPLS-DA distinguished thyroid tumor from normal (Q2=0.37) ○ Increased lactate and taurine in tumor ○ Decreased choline, phosphocholine, myo-inositol, scyllo-inositol in tumor –ROC curve showed prediction accuracy of 77% |

68 | 32 | 45 |

| Torregrossa et al. | 2012 | thyroid | – Permutation-validated OPLS-DA distinguished thyroid tumor from benign tissue (R2Y=0.82, Q2=0.37) ○ Increased phenylalanine, taurine, and lactate in tumor ○ Decreased choline, and choline derivatives (myo- and scyllo-inositol) in tumor ○ ROC curve showed 77% prediction accuracy – Biopsied thyroid lesions often receive an indeterminate diagnosis and require surgical excision for histopathological examination, but metabolomic classification of biopsies may assist in pre-surgical classification |

72 | 28 | 46 |

| Giskeodagard et al. | 2010 | breast | – PLS-DA, BBNs, and PNNs, Bayesian belief networks were used to analyze the important prognostic factors of lymph node and receptor status in breast cancer tissue ○ PLS-DA best predicted estrogen and progesterone receptor status in cancer tissue (44/50 and 39/50 correct classification, respectively) ○ BBN correctly classified 34/50 samples |

160 | 0 | 27 |

1.1.1. Methodological considerations

The reviewed studies have invoked unsupervised or supervised multivariate analytical methods to generate metabolomic profiles. The unsupervised analyses include PCA, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), or self-organizing maps (SOM), while the supervised studies primarily used partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), or support vector machines (SVM). Rigorous analysis requires a training-testing cohort design, with a separate testing cohort to be analyzed when sample size permits, or permutation testing, repeated cross validation, such as Monte Carlo cross validation (MCCV), or leave-one-out approaches in the case of smaller sample sizes. To ensure the relevance of the measured metabolomic profiles with disease status, the metabolomic profiles need to be evaluated for disease-relevant metabolic pathways48.

In addition, HRMAS MRS preserves tissue histopathological structures and thereby enables metabolomic profiles to be directly correlated with the percentage of different pathological features. Mass spectrometry (MS) or mass spectrometry imaging (MSI), in contrast, destroy the sample during metabolite extraction from the tissue (MS) or the laser ablation process of measuring a tissue slice (MSI). While MS techniques are more sensitive and can detect as low as picomolar concentrations rather than just the millimolar concentrations of HRMAS MRS, the selection of ions to detect complicates the MS measurement process. Furthermore, MS measurement takes usually three times longer than MRS. These characteristics, and in particular the preservation of tissue in HRMAS MRS make it especially useful for human cancer tissues since each sample unavoidably contains a heterogeneous mixture of pathological features, such as cancer, stroma, and benign epithelia in prostate tissue, or necrosis and fibrosis/inflammation in other tumors. However, only a few studies actually considered the different pathological components in samples, and thus far there is no uniform analytical approach to account for pathology heterogeneity. In a variety of studies, metabolites were analyzed by percentages of pathological features with linear regression49,50 or least-square regression analyses51–54. Other methods include separating samples into high tumor load (>50%) and low tumor load (<50%) groups55, using PCA56, utilizing a partial volume artifacts approach employed for in vivo imaging57,58, or simply measuring a pure tissue of nanoliter sample size59, which is a technical marvel but challenging for general clinical applications.

Metabolomics has also been investigated in conjunction with its upstream biological processes of genomics and transcriptomics. Correlating HRMAS MRS results with gene mutations and transcript alterations helps to relate the measured metabolomic profiles to all the involved metabolic pathways and assists in sub-classifying cancers26,60–62. The strengths of such multi-modal investigations were demonstrated by use of a machine learning framework which combined metabolomics data and gene transcriptome profiling for human brain tumors; the heterogenous data combination outperformed analysis conducted with either single ‘-omics’ data type63.

HRMAS, as an ex vivo method, has also been correlated with in vivo MRS observations64,65 and with PET and MRI19,64. These studies highlight the ability of HRMAS MRS to complement in vivo imaging modalities in the clinic by offering additional diagnostic or prognostic information, or demonstrate the potential for it to directly translate to clinical applications in vivo MRS.

1.2. Fields of investigation and clinical applications

Metabolomic studies have also extended to cancer pharmacology evaluations for the effects of therapies, such as those seen in primarily breast cancer23,64,66–68 and brain tumor glioblastoma69, and have formed a field now termed as pharmacometabolomics.

The primary goal for the development of HRMAS MRS-based cancer metabolomics is to assist diagnosis and treatment decision-making in the clinic. This can be accomplished by a variety of methods, ranging from needle biopsy to surgical settings, the latter being demonstrated by a study that reported successful distinction between ductal carcinoma in situ lesions with or without an invasive component20. The challenge of determining surgical margins during breast cancer surgery can also be addressed potentially by using metabolic profiles of resected tissue to reduce the potential of re-surgery and risk of recurrence22. To enable utilization of these findings, there has been increasing establishment of automated MRS facilities attached to surgical theaters70.

HRMAS MRS metabolomic measurements of cancer field effects in purely histologically benign tissues from cancerous organs can also be useful for clinical applications. The concept of cancer fields was first termed by Dr. Danely Slaughter in 1953 to describe histological abnormalities in grossly normal-appearing tissue and explain multifocality and local recurrence in oral squamous cell carcinoma71 and is deemed one of the landmark concepts of cancer research in the past 100 years72. However, it has now evolved to describe disease-related molecular alterations in microscopically normal or histologically-benign tissue73, observed in cancers of many organ systems and detectable at the epigenomics74,75, genomics76–80, proteomics81–84, or metabolomics levels31,33,41,50,70,85,86. Metabolomic field effects were reported with a gastrointestinal tumorigenesis APCMin/+ mouse model87, with human esophageal cancer70,85, oral squamous cell carcinoma86, colorectal cancer31, and prostate cancer41,50. Most significantly and of great clinical translational potential, histologically benign tissue adjacent to human colorectal cancer could distinguish tumor stage with higher predictive capacity than results from tumor tissues for prediction of 5-year survival (AUC = 0.88)31. Major findings in ex-vivo MRS studies on metabolomic cancer fields in humans are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Ex-vivo HRMAS MRS studies on metabolomic cancer fields in humans.

Findings related to field effects are reported. Abbreviations: Cho, choline; Cre, creatine; GPCho, Glycerophosphocholine; HbA, histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer; Hb Barrett, histologically benign tissue adjacent to Barrett’s esophagus disease; HC, healthy control; BPH, benign prostate hyperplasia; m-Ino, myo-inositol; PCho, phosphocholine; s-Ino, scyllo-inositol. (+), increase, (−), decrease for the first-mentioned group compared to latter if available.

| Authors | Organ | Individuals (n) | Distance of Hbcancer to cancer (cm) | Primary findings | Key metabolites | Ref | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (n) | |||||||||

| Cancer | Histologically benign at distance to cancer (Hbcancer) | Healthy control (HC) | Others | ||||||

| Stenman et al. | Prostate | 40 cancer patients | n.a. | Hbcancer subgroups: • Discrimination of GS 3+3 and GS 3+4 (m-Ino/s-Ino p=0.002; Cho/Cre p<0.001) outperfomed the discrimination based on the cancer samples • Distance to the nearest tumor was correlated with the m-Ino/s-Ino (p= 0.03) and (GPCho + PCho)/Cre (p<0.001) ratios |

• Myo-inositol m-Ino (GS, distance) • Scyllo-inositol s-Ino (GS, distance) • Creatine Cre (GS, distance) • Choline Cho (GS) • Glycerophosphorylcholine GPCho (distance) • Phosphorylcholine PCho (distance) |

50 | |||

| 41 | 108 | - | - | ||||||

| Reed et al. | Esophagus | 46 cancer patients 7 Barrett esophagus patients 68 HC | ≥ 5 | Hbcancer vs HC • excellent discrimination (AUC=1; p≤0.007) Hbcancer vs Histol. Benign adjacent to Barrett • weak discrimination (AUC=0.7, p=0.03) |

Hbcancer vs HC • 3-hydroxybenzoic acid (+) • Succinate (+) • Sactate (+) • Acetate (+) • formate (+) • Adenosyltriphosphate (+) • Glycerophosphorylcholine (+) Hbcancer vs Histol. Benign adjacent to Barrett • 3-hydroxybenzoic acid (+) |

85 | |||

| 57 | 59 | 68 | HbBarrett 7 Barrett 7 |

||||||

| Yacoub et al. | Esophagus | 35 cancer patients 52 HC |

5–20 |

Hba vs HC • 5% of the profile exhibited a significant progressive change in signal intensity from histologically benign tissue in cancer patients and controls • Detection of cancer in histologically benign samples (aHb vs Hb PC/Glu ratio AUC = 0.84; P < 0.001) |

Phosphocholine (PC) (+) • Glutamate (Glu) (+) • Myo-inositol (+) • Adenosine-containing compounds (+) • Uridine-containing compounds (+) • Inosine (+) |

70 | |||

| 32 | 38 | 53 | - | ||||||

| Jimeńez et al. | Colon, Rectum |

26 cancer patients | 5–10 | Hbcancer subgroups • Distinction of T- and N-stages (T4 vs. T1−3 AUC = 0.80 and N0 vs N1–2 AUC = 0.92) in aHb with higher predictive capability than tumor tissue itself (AUC = 0.75 and AUC = 0.88) • Accurate prediction of 5-year survival (AUC = 0.88) |

T-stages • Valine (+), alanine (+), phenylalanine (+), tyrosine (+), glucose (-), formate (-) N-stages • Leucine (+), phenylalanine (+) 5-year survival • Isobutyrate (+) • Acetate (+) • Choline (+) |

31 | |||

| 22 | 23 | - | - | ||||||

| Vandergrift et al. | Prostate | 158 cancer patients 13 BPH patients 14 HC | n.a. | Hbcancer subgroups • Prostate Cancer Grade Group (PGG) PGG1&2 versus PGG3&4 could be seperated by 7 significantly different regions • The pathological T stages pT = IIab from pT = IIc were seperable in the training (p < 0.0013) and testing (p < 0.0004) cohorts, respectively • Cancer recurrence could be predicted by differentiating patients with and without biochemical recurrence in a canonical analysis on principal components in the testing cohort (accuracy 83%) |

PGG • E.g. myo-Inositol (+), glycerophosphocholine (+), phosphocholine (+), and valine (+) T-stages • Lipids Biochemical recurrence • Choline, phosphocholine, glutamate, myo-inositol |

41 | |||

| Training 20 Testing 7 |

Training 179 Testing 159 |

14 | BPH 15 | ||||||

1.3. Investigation of Prostate Cancer Metabolomic Field Effects

In 2011, Stenman et al reported that key metabolites in histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer vary significantly depending on the GS of the closest cancer50. In histologically-benign tissue samples a GS of 3+3 vs. 3+4 in adjacent cancer at various distances was strongly correlated with myo-inositol/scyllo-inositol (p=0.002) and choline/creatine (p<0.001) ratios. Most recently, we have reported that analyses of histologically benign prostate tissue from cancerous prostates allows differentiations of not only Gleason score but also pathological stage, and recurrence potential of human prostate cancer41. We attributed these distinctions to the existence of metabolomic fields. Since these measurements, in principle, can be carried out at the time of biopsy prior to prostatectomy or other radical procedures, HRMAS MRS metabolomics stand to become a complementary method to aid routine histopathology and assist clinical decision making for cancer diagnosis and treatment planning. This ability would be particularly useful for prostate cancer management, as it could reduce the high number of false negative biopsies by enlarging the biopsy target zones or provide further certainty about the aggressiveness of prostate cancer lesions to prevent overtreatment55. Another use of histologically benign tissue for clinical decision-making is for tackling the challenge of handling Gleason score heterogeneity within one prostate. Stenman et al. found that specimens containing a particular fraction of tumor tissue showed substantially higher inter-sample variations in some spectral regions than non-malignant tissue samples, which suggests that benign tissue may be a more reliable metabolic indicator than cancer tissue.

Stenman et al. also reported that metabolite ratios change with increasing distance from lesion. The distance to the nearest tumor was correlated with the myo-inositol/scyllo-inositol (p = 0.03) and (glyercophosphocholine + phosphocholine)/creatine (P < 0.001) ratios, but they noted it was a significant but weak correlation. Additionally, analyses that examine the effect of distance and Gleason score were not conducted, and only a limited range of GS were included in the study (3+3 and 3+4). Also, the extensiveness of cancer patterns and the crossed effects of pattern and distance were not examined. To further investigate these observed cancer metabolomic field effects, we measured HRMAS MRS metabolomics for multiple tissues sampled systematically throughout prostatectomy-removed cancerous prostates.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Sample Collection

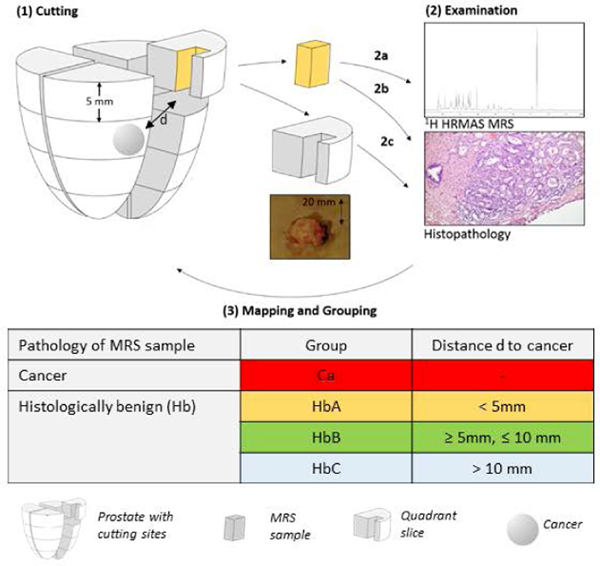

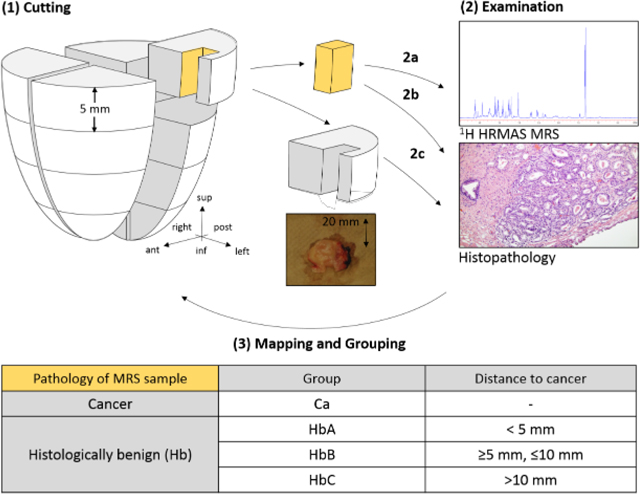

The study was approved by the institutional IRB at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Tissue specimens and related clinical data were collected with written consent from 10 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy at MGH. The patients had not received any cancer treatment prior to surgery. After surgical removal, the organs were kept at 4oC and sectioned within 1 hour. The apex and base were sectioned off. The organ was cut into quarters and slices. Sixteen rectangular ~5mm x 5mm tissue samples about 3 mm away from the margin were collected from the peripheral zone (Figure 1), to preserve surgical margins. Photos of prostate sections where samples were obtained were recorded with a ruler for quantitative measurements. The collected tissue samples were placed on dry ice and then stored at −80oC until MRS analyses. Standard H&E staining (Figure 1) and clinical pathology were performed for the entire removed prostates per routine clinical pathology. Sample collection details are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1. Study Design.

(1) The removed prostate was cut into 16 sections, and a sample was taken from each section, exemplarily only one sample is shown here. (2a) HRMAS 1H MRS. (2b-c) Histopathological examination of both the (2b) MRS-scanned sample and (2c) routine pathology of the remainder of the sections. (3) Three-dimensional categorization system, where the shown sample is assigned to group A according to its histopathology and distance to cancer.

Table 3:

Clinical information summarized for whole prostates and MRS-scanned prostate samples.

| Organs | MRS samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Benign | ||||

| samples (n) median (range) | total | 10 | 26 | 134 | |

| per organ | - | 1.5 (0–9) | 14.5 (7–16) | ||

| Weight (g) median (range) | 50.5 (33.8–70) | - | - | ||

| Vol (cm3) median (range) | 92 (33.75–141.75) | - | - | ||

| Tissue composition (%) median (range) | cancer | 27.5 (10–90) | 19.67 (2–100) | - | |

| benign glands | - | 7.83 (0–31.25) | 9.5 (0–56.27) | ||

| stroma | - | 66.37 (0–83.75) | 90.50 (43.75–100) | ||

| Gleason Score (GS) | low | 3+3 | 1 | 10 | - |

| 3+4 | 4 | 4 | - | ||

| high | 4+3 | 1 | - | - | |

| 4+4 | 1 | 3 | - | ||

| 4+5 | 2 | - | - | ||

| 5+5 | 1 | 9 | - | ||

| Pathological stage (pTNM) | tumor stage | pT2a | 1 | - | - |

| pT2c | 5 | - | - | ||

| pT3a | 3 | - | - | ||

| pT3b | 1 | - | - | ||

| lymph node stage | N1 | 2 | - | - | |

| N0 | 6 | - | - | ||

| NX | 2 | - | - | ||

| Perineural Invasion | 9 | - | - | ||

2.2. HRMAS MRS and Histopathology

HRMAS.

Tissue samples of ~10 mg were scanned using HRMAS MRS on a vertical Bruker AVANCE spectrometer operating at 600 MHz (14.1T) (Figure 1). A 4mm zirconia rotor with Kel-F 10μl inserts was used, with D2O added for field locking. Spectra, with and without water suppression, were recorded at 4oC using a rotor-synchronized Min(A,B) protocol with spinning at 600 and 700 Hz88. Data were processed and curve fit using an in-house developed MATLAB program, and metabolite intensity was calculated by normalizing each curve fitted peak by the intensity of the creatine region (3.03 ppm) from the full integral value of the water-unsuppressed file. Spectral regions between the ppm values 0.5 and 4.5 ppm where >80% of samples had detectable values (n = 63) were further analyzed and matched to corresponding relevant metabolites (Supplementary Table S1). As one region contains several metabolites due to overlapping peaks, we talk about ppm values rather than concrete metabolites thought the manuscript.

2.3. Histopathology.

Following HRMAS MRS, tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4 5-μm sections, and H&E stained (Figure 1). The histopathology analysis was conducted by a single pathologist with >15 years’ experience, blinded to spectroscopic results. Tissue samples were read for percentage of three pathological features (stroma, glands, cancer) to the nearest 5%. Gleason score (GS) and the presence of nerves and vessels, inflammation, low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (LGPIN), and high-grade (HG) PIN were also recorded. The area of each tissue specimen was measured using the software imageJ89. Volume percentage (Vol%) for each pathological feature was calculated for each sample under the assumption of equal thickness of the tissue samples. Clinically-processed prostate slides were examined for the presence, Gleason score, and patterns of cancer to identify the location and nature of cancer lesions throughout the prostate.

2.4. MRS Sample Categorization

We used a categorical system to estimate the three-dimensional distances between the measured tissue samples and the closest cancer lesions. A distance of 5 mm was designated as the cut-off point because when prostates are sectioned after removal, they are cut into 5 mm-thick slices to fit in histopathology processing cassettes. Histologically benign (Hb) samples were assigned to three categorical groups according to their distance to the closest cancer lesion(s) (HbA < 5mm; 5mm ≤ HbB ≤ 10mm; HbC >10mm) and the pattern of the closest cancer lesion, with ‘more’ indicating a cancer pattern to be ‘extensive’ or ‘many’, and ‘less’ to be ‘moderate’, ‘small’, or ‘focal’.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Autoscaling and mean centering was applied to the data set prior to analyses90. Unsupervised (PCA) and supervised (PLS-DA) multivariate statistical analyses were performed. Outliers were identified in the PCA plot (Supplementary Figure S1). The predictive performance Q2 of the PLS-DA model was obtained by 10-fold cross validation (CV). To account for the statistical paradigm of several samples measured from the same patient, a “leave one patient out” CV was conducted. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were determined using cross-validated predictive Y-values of the PLS-DA data, and the area under the curve (AUC) was also calculated for each model. For univariate analysis, Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons were conducted. Relative intensity of fold changes were determined for the discriminant metabolite signals for all models. Analyses were performed in RStudio91 and on the web-based platform MetaboAnalyst92.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Classification

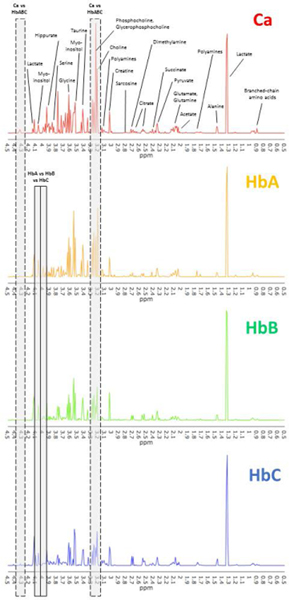

From 10 patients (age: median, 62; range, 53–77 years) with prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma undergoing radical prostatectomy, 16 samples were collected from each prostate, resulting in a total of 160 samples. Characteristics for all cases and MRS-scanned samples are summarized in Table 3. Following three-dimensional mapping of the locations of cancer lesions for each prostate, histologically benign (Hb) samples were assigned to the previously defined three categorical groups according to the distance to the closest cancer and two groups based on cancer patterns (Table 4). Due to the multifocality of prostate cancer, there were only small numbers of samples in the HbB and HbC groups. Thus, these two groups were merged to form group HbBC (n =10) except for analyses at the individual prostate level. lesion(s) In addition, all samples were also grouped based on a ‘low’ (≤3+4) or ‘high’ (≥4+3) Gleason score (GS) of the individual prostate from which they originated according to the pathology reports (Table 4). Four samples of group HbA were excluded due to measurement issues or identification as outliers in the PCA score plot (Supplementary Figure S1). Lastly, percentage of pathological features was compared between sample groups. Univariate comparisons between HbAless vs. HbAmore vs. HbB indicated no significant differences for percentage of benign epithelial glands or stroma (Supplementary Figure S3). Cancer samples were significantly different (all p < 0.002) from each group only for stroma percentage (Supplementary Figure S2). Representative spectra for each group are displayed in Figure 2.

Table 4:

Tissue sample classification system.

| Groups | Subgroups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Distance to closest cancer | Gleason Score | Cancer pattern (scatter, size) | |||||

| ≤ 3+4 | ≥ 4+3 | less | more | |||||

| Cancer Ca | 26 | - | 14 | 12 | - | |||

| Histologically Benign HbABC | 134 | HbA≤ 5mm | 124 | 60 | 60 | 21 | 99 | |

| HbB≥ 5mm, ≤ 10mm | 6 | HbBC 10 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 | ||

| HbC≥ 10mm | 4 | |||||||

Figure 2. Representative spectra for the comparison groups.

Representative spectra for cancer (Ca, top) and histologically benign samples at different distances from cancer (increasing distance; HbA, HbB, HbC). All samples are from the same prostate, which was also used for the analysis on organ level. Metabolites were assigned based on literature values (Supplementary Table S1), and visually distinct peaks are labeled here. Exemplary regions that appeared significant in multivariate analysis are boxed (Ca vs HbABC, cancer versus benign; HbA vs HbB vs HbC, differences between histologically benign tissue at different distances).

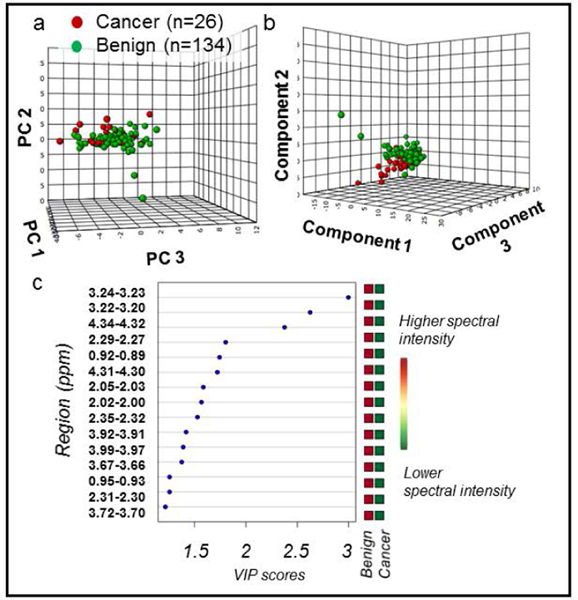

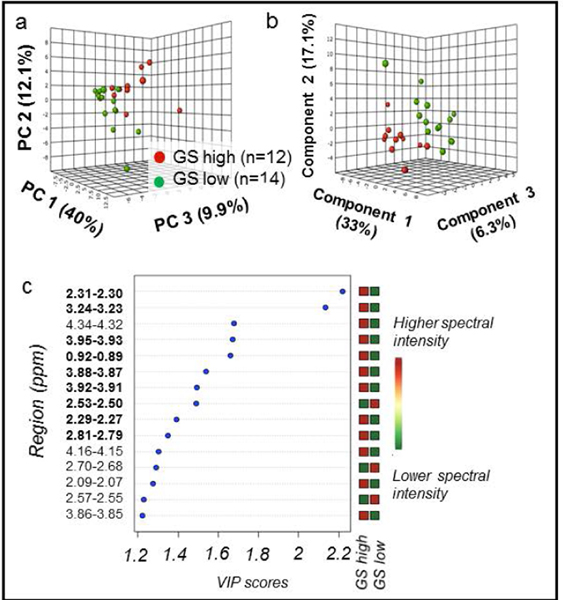

3.2. Cancer samples: Differentiating cancer vs. benign and high vs. low Gleason score

We evaluated the metabolomic differences between cancer and histologically benign samples (Figure 3) and between cancer samples with low (≤3+4) and high (≥4+3) Gleason score (Figure 4). Visual inspection of PCA score plots revealed tendencies for group separation (Figure 3a and Figure 4a, respectively). A 10-fold cross-validated PLS-DA model showed good separation between cancer and benign samples with good predictability (R2Y = 0.33 and Q2Ycum = 0.18, Figure 3b). An excellent separation between CaGS low (≤3+4) and CaGS high (≥4+3) was also achieved among the cancer samples in a 10-fold cross-validated PLS-DA model (R2Y = 0.84 and Q2Ycum = 0.48) (Figure 4b).

Figure 3. PCA and PLS-DA distinguish cancer vs. benign samples.

All MRS-scanned samples, benign (n = 134) vs cancer (n = 26). (a) PCA score plot with PC1 (40.4% of variance), PC2 (8.3%), and PC3 (6%). (b) 10-fold cross-validated PLS-DA score plot (R2Y = 0.33 and Q2Ycum = 0.18). Component 1 explains 35.1% of variance, Component 2 explains 11.1%, and Component 3 explains 5.6%. (c) PLS-DA VIP scores of Component 1 that are >1 and corresponding fold changes for regions are presented. All red squares in the right column indicate that each spectral region had higher intensity in cancer compared with benign samples. All spectral regions listed had VIP > 1 and were also significant in univariate analysis. Metabolites associated with each spectral region can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 4. PCA and PLS-DA distinguish GS among cancer samples.

Cancer samples, with CaGS high defined as ≥4+3 (n = 12) vs. CaGS low as ≤3+4 (n = 14). (a) PCA score plot with PC1 (40% of variance), PC2 (12.1%), and PC3 (9.9%). (b) 10-fold cross-validated PLS-DA score plot (R2Y = 0.84 and Q2Ycum = 0.48) with Component 1 (33% of variance), Component 2 (17.1%), and Component 3 (6.3%). (c) PLS-DA VIP scores of Component 1 that are >1 and corresponding fold changes for regions are presented. A red square indicates that sample group has a higher spectral intensity for a given region. Bold spectral regions indicate which regions both had VIP > 1 and were significant in univariate analysis.

Major contributing regions were identified by applying the criterion of variable importance of projection (VIP) > 1 in the PLS-DA models (Figure 3c and Figure 4c) in combination with p < 0.05 in univariate Wilcoxon rank sum analysis with Benjamini Hochberg false discovery rate adjustment (Supplementary Table S2). In addition to the 15 significant metabolic regions seen in PLS-DA for cancer vs. benign samples (Figure 3c), 4 other regions (2.97–2.95, 2.81–2.79, 2.09–2.07, 1.73–1.71 ppm) were also significant in univariate analysis. All 19 regions showed increased spectral intensities in cancer when compared with histo-benign samples. Among the most significant metabolites are taurine, phosphocholine and lipids. For the differentiation of CaGS high versus CaGS low, univariate analysis revealed 10 significantly different regions, with 5 shared among the above 19 regions. Apart from the 3.90–3.89 ppm and 2.45–2.43 ppm regions, the remaining eight regions were also identified in the multivariate model (Figure 4c). For these 10 regions from the univariate analysis, the spectral intensities were increased in the CaGS high group for all except 2.53–2.50 ppm (Supplementary Table S3). Glutamate, taurine and tyrosine were identified as major distinguishing metabolites. Remaining relevant metabolites associated with each spectral region are located in Supplementary Table S1.

3.3. Histologically benign samples close to cancer (HbA): Distinguishing between cancer grade and pattern

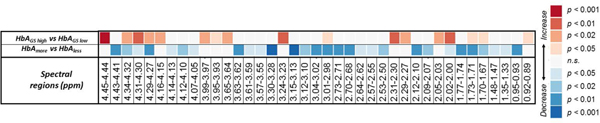

Prostate tissue metabolomics revealed differences in cancer status between tissue groups that were histologically benign. In univariate analysis, we identified significantly different regions by comparing histologically benign tissue (HbA) in a prostate of low GS (≤3+4) (n = 60) with high GS (≥4+3) (n = 60). All 29 significant spectral regions showed higher values for HbAGS low (Supplementary Table S4). Analysis of benign tissue adjacent to more extensive patterns of cancer (HbAmore, n = 99) revealed 17 significantly different regions that all presented higher values than benign tissue near less extensive cancer (HbAless, n = 21) (Figure 5) (Supplementary Table S5). The majority of significant regions were unique for each of these comparisons, as only 7 regions were overlapped between the two. The two comparison groups of cancer pattern and GS are not correlated, meaning that in Wilcoxon comparisons there were no significant differences of the distribution of cancer pattern samples in the HbAGS high vs. HbAGS low subgroups and no significant difference of GS in the HbAmore vs. HbAless groups.

Figure 5. Univariate comparisons within the HbA group.

Wilcoxon rank sum comparisons between HbAmore (n = 99) vs. HbAless (n = 21) and HbAGS high (n = 60) vs. HbAGS low (n = 60) indicated several spectral regions which could differentiate between the subgroups with Benajmini-Hochberg adjustment. The red square in the upper left indicates that HbAmore had significantly higher (p<0.001) intensity in the 4.45–4.44 ppm region than did HbAless. The blue square of 4.43–4.41 ppm indicates that HbAGS high has lower intensity than AGS low. Abbreviation: n.s., not significant.

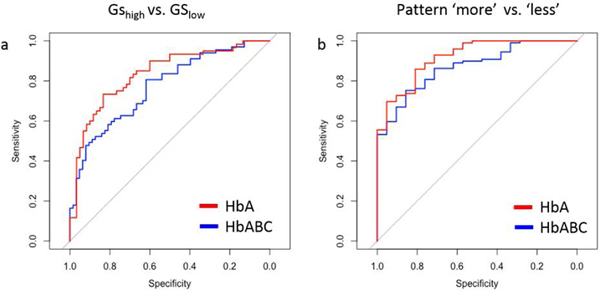

In a comparison of all benign tissue (HbABC), differentiation between GS groups and closest cancer pattern presented fewer significant regions than when only the above-mentioned benign tissues closest to cancer (HbA) were considered. For the comparison of the GS group using all benign tissue when distance to the closest cancer was not considered (HbABCGS low vs. HbABCGS high), four regions that were discriminatory in the analysis of exclusively HbAGS low vs. HbAGS high were no longer significant (4.14–4.13, 4.07–4.05, 2.64–2.62, 2.02–2.00 ppm). Only one region appeared significant that was not significant previously (3.95–3.93 ppm) (p = 0.047, Supplementary Table S6). The same reduction of significant regions occurred when all benign samples, regardless of distance to cancer, were grouped together for analysis of adjacent cancer patterns (HbABCmore vs. HbABCless). Specifically, two regions that were important in the analysis of exclusively HbA were no longer significant (1.73–1.71, 0.92–0.89 ppm), and only one region appeared significant that was not significant previously (3.67–3.66 ppm) (p = 0.044, Supplementary Table S7). Furthermore, predictive ability for both GS and cancer pattern comparisons improved when using only the HbA samples. For differentiating high and low GS with HbA and with HbABC samples, the area under the curve (AUC) = 0.83 (95% CI: 0.761–0.908) and AUC = 0.765 (95% CI: 0.690–0.850), respectively (Figure 6a). For distinguishing cancer patterns, only using HbA samples achieved AUC = 0.918 (95% CI: 0.857–0.978) and HbABC samples had AUC = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.800–0.941) (Figure 6b).

Figure 6. Improved prediction accuracy when considering distance to closest cancer.

To generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, all spectral regions significant in the respective univariate analyses were subject to logistic regression. ROC curves were generated from the resulting fitted values. (a) HbA (red) and HbABC (blue) samples were used to predict GShigh vs. GSlow with HbA AUC = = 0.83 (95% CI: 0.761–0.908) and HbABC AUC = 0.765 (95% CI: 0.690–0.850), respectively. (b) HbA (red) and HbABC (blue) samples were used to predict ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ with HbA AUC = 0.918 (95% CI: 0.857–0.978) and HbABC AUC = 0.870 (95% CI: 0.800–0.94), respectively. For both comparisons, prediction accuracy was increased when the samples close to cancer were separated from samples far from cancer.

3.4. All histologically benign samples: Characterization of the field effect

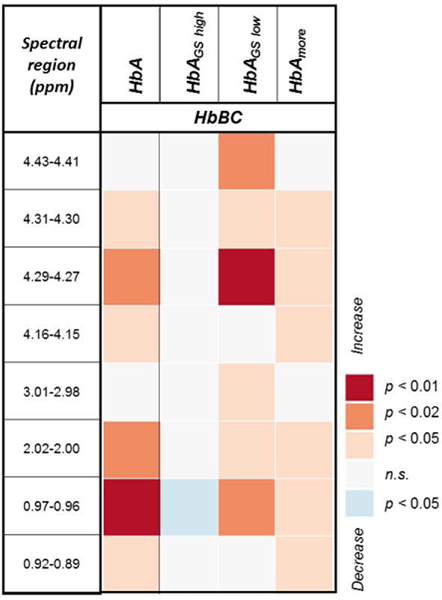

A univariate analysis of benign samples of all organs revealed that with decreasing distance from cancer (HbA compared to HbBC), six regions were found to increase significantly in spectral intensity (first column in Figure 7 and Supplementary Table S8), most importantly valine and phosphocholine. The 2.02–2.00 and 0.92–0.89 ppm regions, which were significant in Figure 7, were also significant in the above-mentioned comparisons of GS and cancer pattern, but only when distance from cancer was considered for benign samples. This discrepancy further suggests the existence of distance-dependent metabolomic fields. Subsequent comparisons of HbBC and various subgroups of HbA suggested that the metabolic differences between the two groups are present for benign samples from low GS prostates (HbAGS low, third column) and for benign samples adjacent to more extensive cancers (HbAmore, fourth column). However, distance-dependent metabolic differences are diminished between HbAGS high and HbBC samples (second column) and are nonexistent between HbAless and HbBC samples (none to report).

Figure 7. Univariate comparisons between HbA and HbA subgroups vs. HbBC.

Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon comparisons between HbA (n = 124) vs. HbBC (n = 10), HbAGS high (n = 60) vs. HbBC, HbAGS low (n = 60) vs. HbBC, and HbAmore (n = 99) vs. HbBC indicated several spectral regions which could differentiate between the subgroups with Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment. The orange square in the top row indicates that HbAGS low had significantly higher (p<0.02) intensity in the 4.43–4.41 ppm region than did HbB. There were no regions significantly different between HbAless vs. HbBC.

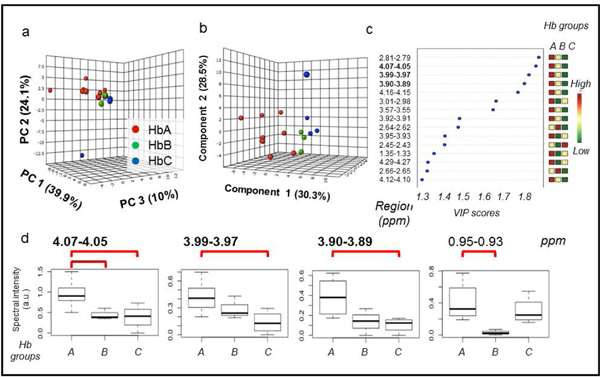

3.5. Within a single prostate: HbA vs HbB vs HbC groups

Since 7 out of 10 samples of the merged group HbBC originated from a single prostate, an analysis was carried out for HbA (n = 8) vs. HbB (n = 4) vs. HbC (n = 3) because the small sample size is not confounded by between-patient effects. A PCA score plot revealed a clear trend of group separation (Figure 8a). A leave-one-out cross-validated PLS-DA model showed excellent separation between the three subgroups and explained a large percentage of variability with good predictability (R2Y = 0.63 and Q2Y = 0.18, Figure 8b). Three of the four regions that were found to be significant in univariate analysis (Supplementary Table S9) were confirmed by multivariate analysis (4.07–4.05, 3.99–3.97, and 3.90–3.89 ppm). In all three regions, spectral intensity and distance to cancer were inversely correlated (Figure 8d), a trend that was also seen in analysis of all samples (Figure 7).

Figure 8. Within-organ analysis for a single prostate case.

(a) PCA score plot with PC1, PC2, and PC3, explaining 39.9%, 24.1%, and 10% of the variance, respectively. (b) 10-fold cross-validated PLS-DA score plot (R2Y = 0.63 and Q2Y = 0.18) with Component 1 (30.3% of variance), Component 2 (28.5%), and Component 3 (11.1%). (c) PLS-DA VIP scores of Component 1 that are >1 and corresponding fold changes for regions are presented. The three colored columns correspond to HbA, HbB, and HbC groups. Colors indicate relative intensity for each group. For example, the first row that is red, yellow and green from left to right indicates that spectral intensity is highest for HbA samples, of middle intensity for HbB samples, and lowest for HbC samples, for the 2.81–2.79 ppm region. Bold spectral regions indicate which regions had VIP > 1 and were significant in univariate analysis. (d) Four regions which were significant in univariate Wilcoxon rank sum analysis of HbA, HbB, and HbC are shown. Red brackets indicate which pairwise comparisons were significant with Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate adjustment. Inter-quartile range is illustrated by the dashed lines. 4.07–4.05 ppm, 3.99–3.97 ppm, 3.90–3.89 ppm, 0.95–0.93 ppm. Standard deviation, mean and confidence interval can be found in Supplementary Table S9.

4. Discussion

A large body of literature data demonstrated the strength of MRS-based metabolomics in disease assessment due to the close association of metabolomics and disease phenotypes. By considering the ensemble of all measurable low-molecular weight metabolites in a biological system, many ex vivo metabolomics studies have indicated the greater sensitivity of global metabolite profiles, with or without univariate metabolite analysis, in representing disease status compared to single metabolites8,29,93–95. While ex vivo metabolomics evaluations can assist current clinical diagnosis and staging by providing biological information that cannot be obtained by histological evaluation41, through the existence of cancer field effects, translating ex vivo findings to in vivo methods is the ultimate aim. A current challenge to this translation is that in vivo MRS studies typically focus on a select few, high-intensity metabolites96, primarily due to resolution constraints. Nevertheless, results from the examination of whole, cancerous prostates on a 7T MR scanner indicated the potential of metabolomics for in vivo MRS, where metabolomic profiles measured from the removed prostates located cancer lesions with overall 93% accuracy97. Promising results from a comparison between in vivo MRS and ex vivo HRMAS MRS measurement of prostates and prostate tissue, respectively, further suggested that ex vivo metabolomics can be translated to clinical evaluations. In this study, the metabolic ratio of (choline + citrate + spermine)/citrate in prostate cancer showed strong positive correlations between the ex vivo and in vivo measurements98.

In contrast to in vivo measurements, ex vivo HRMAS MRS confers an advantage for metabolomic measurement by allowing intact tissue measurement. This aspect of the method enables histopathological assessment and thereby calibration according to pathological features of each individual tissue sample, as well as examination of other -omics levels for an inclusive systems biology approach.

As a demonstration of the potential of HRMAS MRS metabolomics, our measurements of histologically benign samples collected from cancerous prostates can correlate with both the Gleason score of the whole prostates and the pattern of the closest cancer lesion. These results, achieved with histo-benign tissue that was <5 mm from cancer (HbA), support the concept of tissue metabolomics in characterizing disease beyond the ability of routine histopathology31,33,41,50,70,85,86. Particularly, our results indicated the existence of a measurable scale of metabolomic fields. This finding was indicated by the reduction of the number of significant metabolic regions and decreased prediction accuracy (Figure 6) in distinguishing GS of the prostate and cancer patterns when all histo-benign samples are considered as a single group when compared with distinguishing with just the cancer-close HbA group.

Our findings regarding specific metabolites agree with those reported elsewhere. Elevated phosphocholine and glycerophosphocholine were identified in esophageal cancer70 and the enzyme which forms phosphocholine was found overexpressed in several cancers99. Previous studies characterizing prostate cancer field effects found myo-inositol41 and ratios of myo-inositol/scyllo-inositol and (glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine)/creatine50 to be altered. At organ level, our analysis confirmed altered levels of the metabolites phosphocholine and creatine, as well as myo-inositol and glycophosphocholine. Previously, some of these metabolites were shown to be independent of possibly confounding factors, such as prostate tissue composition of glands and stroma for choline levels or patients age for myo-inositol100,101 . Previously altered levels of these metabolites were assigned to processes in cancer, such as altered levels of choline compounds were assigned to membraneogenesis for cancer cell proliferation, creatine was assigned to cancer energy metabolism102 and my-inositol was suggested to be an osmo-regulator101 and binding factor for polyamines103. Of special interest are polyamines, as the prostate gland has the highest levels of polyamines and they were repeatedly shown to metabolomically differentiate cancer from healthy prostate tissue and different grades of gleason score39,52. Interestingly, we found polyamine levels to vary in histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer depending on the GS of the cancer itself.

Figure 7 further presents the influence of cancer lesion extent on the measured metabolomic profiles of benign tissue. Although the group of benign samples close to cancer (HbA) could be distinguished from the group of benign samples far from cancer (HbBC), HbBC samples were not distinguishable from benign samples adjacent to a cancer lesion that is less extensive (HbAless). HbBC samples were, however, significantly different from those adjacent to more extensive cancer (HbAmore). Possibly a threshold quantity of cancer cells is needed to make a metabolomic field arise, and less extensive lesions may not exert enough influence to cause HbAless to be different from samples further away (HbBC). Alternatively, certain conditions may change the scale of metabolomic fields. This latter consideration may be illustrated by the fact that benign samples far from cancer were barely distinguishable from benign samples close to cancer for a prostate with a high Gleason score, but were very distinct from benign, cancer-proximate samples of a prostate with a low Gleason score. We hypothesize that the effect of a high GS cancerous lesion may be so great that its metabolomic field extends beyond the distance of 5 mm, as there is no longer a change of metabolic intensity for most metabolites at that point as defined for this study. These findings regarding metabolomic field effects suggest caution when using benign tissue samples as controls in biomarker studies as is often done, especially in prostate cancer research104, due to the difficulty of obtaining truly cancer-free organs105. We urge that distance from and pattern of the nearest cancer lesion should be considered. The fact that histologically benign samples can provide information regarding cancer status affirms that metabolomic fields can help overcome diagnostic challenges of prostate cancer by potentially enlarging the target biopsy zone to help reduce false negatives105.

This above explanation assumes that cancer causes the metabolomic field, but Slaughter et al. originally proposed that an altered molecular field may be the precursor of cancer71. Under this hypothesis, different metabolomic fields may result in the more or less aggressive Gleason scores or varied patterns of cancer that we observed were distinguishable with benign tissue. There is likely bi-directional interplay between lesions and fields.

Future explorations will help elucidate the relationship between metabolomic lesions and fields, as would genetic-metabolomic correlations. One limitation of this study is that only metabolomic evaluations were investigated. A second limitation was the multifocality of prostate cancer – the existence of multiple lesions throughout the prostate - which meant that the total number of samples at far distances from cancer was small. Of the ten prostates examined, only three had samples in both categorization groups of ‘5–10mm’ and ‘>10mm’ from cancer, and seven had only samples <5mm from cancer. Unequal sample size also prevented a satisfactory multivariate model from being constructed and evaluated to rigorously evaluate the difference between HbA and HbBC groups, so two comparisons were performed:. A comparison of HbA versus HbBC (all benign samples from all organs) and a comparison of HbA versus HbB versus HbC (benign samples from one organ). As a result, different significant metabolites were identified for each, which can be explained by the aggregation of the HbB and HbC groups in the first comparison106. Mismatched group size was especially problematic for the already small group of benign samples 5–10mm from cancer because seven of the ten specimens were from the same patient. Thus, it is also possible that comparisons of all benign tissue close to cancer (HbA) versus benign tissue further from cancer (HbBC) reflect interpersonal differences rather than generalizable effects. Nevertheless, within one prostate in Figure 8, where inter-patient differences are nonexistent, metabolomic profiles measured from all three benign tissue groups indeed indicated the possibility of quantifying the metabolomic field scale with the current method.

Ultimately, since sample classification in this report is a semi-quantitative estimate, a more extensive characterization system must be invoked, where cancer lesions and MRS-scanned sample location can be quantitatively pinpointed in three-dimensional space. Histopathological three-dimensional reconstruction of prostate cancer architecture, as undertaken by Tolkach and colleagues107, may enable this localization and allow characterization of metabolomic fields at intervals even smaller than 5 mm.

5. Conclusions

Our review of the current state of HRMAS MRS-based investigations of cancer indicated that multivariate methods of metabolomics, with or without information provided by univariate analyses, are superior to univariate methods alone. Building upon the concept of metabolomic field effects, we report a semi-quantitative, three-dimensional method of mapping cancer lesions and scanned samples which enabled the distance-dependent existence of metabolomic fields and particularities regarding pathological features of the closest cancer to be identified in prostates. This study with its proof-of-principle distinction of cancer versus benign tissue and characterization of new aspects of cancer fields in histologically benign tissue opens the path to myriad applications of the phenomenon of metabolomic field effects, ranging from decreasing false negatives during prostate biopsy to defining tumor margins in a variety of organ systems.

Supplementary Material

Review Criteria.

PubMed was searched for articles about metabolomics of human cancer tissue, using the following criteria: [(cancer) AND (hrmas OR high resolution magic angle spinning)) AND (metabo* OR pca OR pls da OR pls-da OR discriminant analysis OR linear discriminant analysis OR canonical analysis OR unsupervised OR hierarchical cluster analysis OR self-organizing maps OR supervised]. The search was performed on October 20, 2017, and the resulting 132 papers were reviewed for inclusion. Additional relevant papers discovered in the references of included studies were screened for inclusion. Reviews, studies with animals or cells, and in vivo-only studies were excluded, which resulted in 39 papers to be included in the review.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Massachusetts General Hospital Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01CA115746 and R21CA162959 (Cheng). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- Cho

choline

- Cre

creatine

- GPCho

Glycerophosphocholine

- GS

Gleason score

- HbA

histologically benign tissue adjacent to cancer

- Hb Barrett

histologically benign tissue adjacent to Barrett’s esophagus disease

- HC

healthy control

- MCCV

Monte-Carlo cross validation

- m-Ino

myo-inositol

- OPLS-DA

orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PCho

phosphocholine

- PLS-DA

partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- s-Ino

scyllo-inositol

- SVM

support vector machines

References

- 1.Mortality GBD, Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13(4):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng LL, Lean CL, Bogdanova A, et al. Enhanced resolution of proton NMR spectra of malignant lymph nodes using magic-angle spinning. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1996;36(5):653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson MG, Vigneron DB, Tabatabai ZL, et al. Proton HR-MAS spectroscopy and quantitative pathologic analysis of MRI/3D-MRSI-targeted postsurgical prostate tissues. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2003;50(5):944–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng LL, Chang IW, Louis DN, Gonzalez RG. Correlation of high-resolution magic angle spinning proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy with histopathology of intact human brain tumor specimens. Cancer research. 1998;58(9):1825–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng LL, Chang IW, Smith BL, Gonzalez RG. Evaluating human breast ductal carcinomas with high-resolution magic-angle spinning proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of magnetic resonance (San Diego, Calif : 1997). 1998;135(1):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng LL, Ma MJ, Becerra L, et al. Quantitative neuropathology by high resolution magic angle spinning proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(12):6408–6413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tate AR, Foxall PJ, Holmes E, et al. Distinction between normal and renal cell carcinoma kidney cortical biopsy samples using pattern recognition of (1)H magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectra. NMR in biomedicine. 2000;13(2):64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imperiale A, Moussallieh FM, Roche P, et al. Metabolome profiling by HRMAS NMR spectroscopy of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas detects SDH deficiency: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Neoplasia (New York, NY). 2015;17(1):55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imperiale A, Moussallieh FM, Sebag F, et al. A new specific succinate-glutamate metabolomic hallmark in SDHx-related paragangliomas. PloS one. 2013;8(11):e80539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imperiale A, Elbayed K, Moussallieh FM, et al. Metabolomic profile of the adrenal gland: from physiology to pathological conditions. Endocrine-related cancer. 2013;20(5):705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavel L, Fontana F, Garcia Manteiga JM, et al. Assessing Heterogeneity of Osteolytic Lesions in Multiple Myeloma by (1)H HR-MAS NMR Metabolomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dali-Youcef N, Froelich S, Moussallieh FM, et al. Gene expression mapping of histone deacetylases and co-factors, and correlation with survival time and 1H-HRMAS metabolomic profile in human gliomas. Scientific reports. 2015;5:9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperiale A, Elbayed K, Moussallieh FM, et al. Metabolomic pattern of childhood neuroblastoma obtained by (1)H-high-resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS) NMR spectroscopy. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011;56(1):24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuellar-Baena S, Morales JM, Martinetto H, et al. Comparative metabolic profiling of paediatric ependymoma, medulloblastoma and pilocytic astrocytoma. International journal of molecular medicine. 2010;26(6):941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monleon D, Morales JM, Gonzalez-Darder J, et al. Benign and atypical meningioma metabolic signatures by high-resolution magic-angle spinning molecular profiling. Journal of proteome research. 2008;7(7):2882–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erb G, Elbayed K, Piotto M, et al. Toward improved grading of malignancy in oligodendrogliomas using metabolomics. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2008;59(5):959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haukaas TH, Euceda LR, Giskeodegard GF, et al. Metabolic clusters of breast cancer in relation to gene- and protein expression subtypes. Cancer & metabolism. 2016;4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon H, Yoon D, Yun M, et al. Metabolomics of Breast Cancer Using High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: Correlations with 18F-FDG Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography, Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced and Diffusion-Weighted Imaging MRI. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0159949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chae EY, Shin HJ, Kim S, et al. The Role of High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy for Predicting the Invasive Component in Patients with Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Diagnosed on Preoperative Biopsy. PloS one. 2016;11(8):e0161038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao MD, Lamichhane S, Lundgren S, et al. Metabolic characterization of triple negative breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2014;14:941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bathen TF, Geurts B, Sitter B, et al. Feasibility of MR metabolomics for immediate analysis of resection margins during breast cancer surgery. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JS, Baek HM, Kim S, et al. Magnetic resonance metabolic profiling of breast cancer tissue obtained with core needle biopsy for predicting pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e83866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giskeodegard GF, Lundgren S, Sitter B, et al. Lactate and glycine-potential MR biomarkers of prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. NMR in biomedicine. 2012;25(11):1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Song Y, Cho N, et al. An HR-MAS MR metabolomics study on breast tissues obtained with core needle biopsy. PloS one. 2011;6(10):e25563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borgan E, Sitter B, Lingjaerde OC, et al. Merging transcriptomics and metabolomics--advances in breast cancer profiling. BMC cancer. 2010;10:628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giskeodegard GF, Grinde MT, Sitter B, et al. Multivariate modeling and prediction of breast cancer prognostic factors using MR metabolomics. Journal of proteome research. 2010;9(2):972–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitter B, Bathen TF, Singstad TE, et al. Quantification of metabolites in breast cancer patients with different clinical prognosis using HR MAS MR spectroscopy. NMR in biomedicine. 2010;23(4):424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sitter B, Lundgren S, Bathen TF, Halgunset J, Fjosne HE, Gribbestad IS. Comparison of HR MAS MR spectroscopic profiles of breast cancer tissue with clinical parameters. NMR in biomedicine. 2006;19(1):30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian Y, Xu T, Huang J, et al. Tissue Metabonomic Phenotyping for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Human Colorectal Cancer. Scientific reports. 2016;6:20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jimenez B, Mirnezami R, Kinross J, et al. 1H HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy of tumor-induced local metabolic “field-effects” enables colorectal cancer staging and prognostication. Journal of proteome research. 2013;12(2):959–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan EC, Koh PK, Mal M, et al. Metabolic profiling of human colorectal cancer using high-resolution magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (HR-MAS NMR) spectroscopy and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Journal of proteome research. 2009;8(1):352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Wang L, Wang S, et al. Study of metabonomic profiles of human esophageal carcinoma by use of high-resolution magic-angle spinning 1H NMR spectroscopy and multivariate data analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405(10):3381–3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rocha CM, Barros AS, Goodfellow BJ, et al. NMR metabolomics of human lung tumours reveals distinct metabolic signatures for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(1):68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Battini S, Faitot F, Imperiale A, et al. Metabolomics approaches in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: tumor metabolism profiling predicts clinical outcome of patients. BMC medicine. 2017;15(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen AF, Sandsmark E, Rye MB, et al. Presence of TMPRSS2-ERG is associated with alterations of the metabolic profile in human prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(27):42071–42085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madhu B, Shaw GL, Warren AY, Neal DE, Griffiths JR. Response of Degarelix treatment in human prostate cancer monitored by HR-MAS 1H NMR spectroscopy. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2016;12:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang VY, Westphalen A, Delos Santos L, et al. The role of metabolic imaging in radiation therapy of prostate cancer. NMR in biomedicine. 2014;27(1):100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giskeodegard GF, Bertilsson H, Selnaes KM, et al. Spermine and citrate as metabolic biomarkers for assessing prostate cancer aggressiveness. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e62375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burns MA, He W, Wu CL, Cheng LL. Quantitative pathology in tissue MR spectroscopy based human prostate metabolomics. Technology in cancer research & treatment. 2004;3(6):591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandergrift LA, Decelle EA, Kurth J, et al. Metabolomic Prediction of Human Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness: Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of Histologically Benign Tissue. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan K, He W, Halpern E, Wu C, Cheng L. Evaluation of tissue metabolites with high resolution magic angle spinning MR spectroscopy human prostate samples after three-year storage at −80 °C. Biomarker insights. 2007;2:147–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mun JH, Lee H, Yoon D, Kim BS, Kim MB, Kim S. Discrimination of Basal Cell Carcinoma from Normal Skin Tissue Using High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning 1H NMR Spectroscopy. PloS one. 2016;11(3):e0150328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung J, Jung Y, Bang EJ, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis and evaluation of curative surgery for gastric cancer by using NMR-based metabolomic profiling. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014;21 Suppl 4:S736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miccoli P, Torregrossa L, Shintu L, et al. Metabolomics approach to thyroid nodules: a high-resolution magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance-based study. Surgery. 2012;152(6):1118–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torregrossa L, Shintu L, Nambiath Chandran J, et al. Toward the reliable diagnosis of indeterminate thyroid lesions: a HRMAS NMR-based metabolomics case of study. Journal of proteome research. 2012;11(6):3317–3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jordan KW, Adkins CB, Cheng LL, Faquin WC. Application of magnetic-resonance-spectroscopy- based metabolomics to the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Acta cytologica. 2011;55(6):584–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alonso A, Marsal S, Julia A. Analytical methods in untargeted metabolomics: state of the art in 2015. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esteve V, Celda B, Martinez-Bisbal MC. Use of 1H and 31P HRMAS to evaluate the relationship between quantitative alterations in metabolite concentrations and tissue features in human brain tumour biopsies. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;403(9):2611–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stenman K, Stattin P, Stenlund H, Riklund K, Grobner G, Bergh A. H HRMAS NMR Derived Bio-markers Related to Tumor Grade, Tumor Cell Fraction, and Cell Proliferation in Prostate Tissue Samples. Biomarker insights. 2011;6:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzika AA, Cheng LL, Goumnerova L, et al. Biochemical characterization of pediatric brain tumors by using in vivo and ex vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(6):1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng LL, Wu C, Smith MR, Gonzalez RG. Non-destructive quantitation of spermine in human prostate tissue samples using HRMAS 1H NMR spectroscopy at 9.4 T. FEBS Lett. 2001;494(1–2):112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng LL, Anthony DC, Comite AR, Black PM, Tzika AA, Gonzalez RG. Quantification of microheterogeneity in glioblastoma multiforme with ex vivo high-resolution magic-angle spinning (HRMAS) proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuro-oncol. 2000;2(2):87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vettukattil R, Gulati M, Sjobakk TE, et al. Differentiating diffuse World Health Organization grade II and IV astrocytomas with ex vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(2):186–195; discussion 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Asten JJ, Cuijpers V, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa C, et al. High resolution magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy for metabolic assessment of cancer presence and Gleason score in human prostate needle biopsies. MAGMA. 2008;21(6):435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jordan KW, Adkins CB, Su L, et al. Comparison of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the lung by metabolomic analysis of tissue-serum pairs. Lung cancer. 2010;68(1):44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Opstad KS, Bell BA, Griffiths JR, Howe FA. Toward accurate quantification of metabolites, lipids, and macromolecules in HRMAS spectra of human brain tumor biopsies using LCModel. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2008;60(5):1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Croitor Sava A, Martinez-Bisbal MC, Van Huffel S, Cerda JM, Sima DM, Celda B. Ex vivo high resolution magic angle spinning metabolic profiles describe intratumoral histopathological tissue properties in adult human gliomas. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2011;65(2):320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong A, Jimenez B, Li X, et al. Evaluation of high resolution magic-angle coil spinning NMR spectroscopy for metabolic profiling of nanoliter tissue biopsies. Analytical chemistry. 2012;84(8):3843–3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bertilsson H, Tessem MB, Flatberg A, et al. Changes in gene transcription underlying the aberrant citrate and choline metabolism in human prostate cancer samples. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18(12):3261–3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos CF, Kurhanewicz J, Tabatabai ZL, et al. Metabolic, pathologic, and genetic analysis of prostate tissues: quantitative evaluation of histopathologic and mRNA integrity after HR-MAS spectroscopy. NMR in biomedicine. 2010;23(4):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzika AA, Astrakas L, Cao H, et al. Combination of high-resolution magic angle spinning proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and microscale genomics to type brain tumor biopsies. International journal of molecular medicine. 2007;20(2):199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Metsis V, Huang H, Andronesi OC, Makedon F, Tzika A. Heterogeneous data fusion for brain tumor classification. Oncology reports. 2012;28(4):1413–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen LR, Huuse EM, Bathen TF, et al. Assessment of early docetaxel response in an experimental model of human breast cancer using DCE-MRI, ex vivo HR MAS, and in vivo 1H MRS. NMR in biomedicine. 2010;23(1):56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tugnoli V, Schenetti L, Mucci A, et al. Ex vivo HR-MAS MRS of human meningiomas: a comparison with in vivo 1H MR spectra. International journal of molecular medicine. 2006;18(5):859–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao MD, Giskeodegard GF, Bathen TF, et al. Prognostic value of metabolic response in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC cancer. 2012;12:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cao MD, Sitter B, Bathen TF, et al. Predicting long-term survival and treatment response in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy by MR metabolic profiling. NMR in biomedicine. 2012;25(2):369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morvan D Functional metabolomics uncovers metabolic alterations associated to severe oxidative stress in MCF7 breast cancer cells exposed to ascididemin. Marine drugs. 2013;11(10):3846–3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun Z, Shi S, Li H, et al. Evaluation of resveratrol sensitivities and metabolic patterns in human and rat glioblastoma cells. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2013;72(5):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yakoub D, Keun HC, Goldin R, Hanna GB. Metabolic profiling detects field effects in nondysplastic tissue from esophageal cancer patients. Cancer research. 2010;70(22):9129–9136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6(5):963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lippman SM, Hawk ET. Cancer prevention: from 1727 to milestones of the past 100 years. Cancer research. 2009;69(13):5269–5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, et al. Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2015;28(1):14–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giovannucci E, Ogino S. DNA methylation, field effects, and colorectal cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(18):1317–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ushijima T Epigenetic field for cancerization: its cause and clinical implications. BMC Proc. 2013;7 Suppl 2:K22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haaland CM, Heaphy CM, Butler KS, Fischer EG, Griffith JK, Bisoffi M. Differential gene expression in tumor adjacent histologically normal prostatic tissue indicates field cancerization. Int J Oncol. 2009;35(3):537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Umbricht CB, Evron E, Gabrielson E, Ferguson A, Marks J, Sukumar S. Hypermethylation of 14–3-3 sigma (stratifin) is an early event in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20(26):3348–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kamiyama H, Suzuki K, Maeda T, et al. DNA demethylation in normal colon tissue predicts predisposition to multiple cancers. Oncogene. 2012;31(48):5029–5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spitzwieser M, Holzweber E, Pfeiler G, Hacker S, Cichna-Markl M. Applicability of HIN-1, MGMT and RASSF1A promoter methylation as biomarkers for detecting field cancerization in breast cancer. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2015;17:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guo H, Zeng W, Feng L, et al. Integrated transcriptomic analysis of distance-related field cancerization in rectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):61107–61117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jones AC, Antillon KS, Jenkins SM, et al. Prostate field cancerization: deregulated expression of macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC-1) and platelet derived growth factor A (PDGF-A) in tumor adjacent tissue. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0119314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gabriel KN, Jones AC, Nguyen JP, et al. Association and regulation of protein factors of field effect in prostate tissues. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(4):1541–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roesch-Ely M, Nees M, Karsai S, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals successive aberrations in protein expression from healthy mucosa to invasive head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(1):54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kadara H, Wistuba, II. Field cancerization in non-small cell lung cancer: implications in disease pathogenesis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(2):38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reed MA, Singhal R, Ludwig C, et al. Metabolomic Evidence for a Field Effect in Histologically Normal and Metaplastic Tissues in Patients with Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia (New York, NY). 2017;19(3):165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Srivastava S, Roy R, Gupta V, Tiwari A, Srivastava AN, Sonkar AA. Proton HR-MAS MR spectroscopy of oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues: an ex vivo study to identify malignancy induced metabolic fingerprints. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society. 2011;7(2):278–288. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Backshall A, Alferez D, Teichert F, et al. Detection of metabolic alterations in non-tumor gastrointestinal tissue of the Apc(Min/+) mouse by (1)H MAS NMR spectroscopy. Journal of proteome research. 2009;8(3):1423–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Burns MA, Taylor JL, Wu CL, et al. Reduction of spinning sidebands in proton NMR of human prostate tissue with slow high-resolution magic angle spinning. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2005;54(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9(7):671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]