Abstract

A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 and has caused over 240,000 cases of COVID-19 worldwide as of March 19, 2020. Previous studies have supported an epidemiological hypothesis that cold and dry environments facilitate the survival and spread of droplet-mediated viral diseases, and warm and humid environments see attenuated viral transmission (e.g., influenza). However, the role of temperature and humidity in transmission of COVID-19 has not yet been established. Here, we examine the spatial variability of the basic reproductive numbers of COVID-19 across provinces and cities in China and show that environmental variables alone cannot explain this variability. Our findings suggest that changes in weather alone (i.e., increase of temperature and humidity as spring and summer months arrive in the Northern Hemisphere) will not necessarily lead to declines in case count without the implementation of extensive public health interventions.

Introduction

Since December 2019, an increasing number of pneumonia cases caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) have been identified in Wuhan, China (1,2). This new pathogen has exhibited high human-to-human transmissibility with approximately 242,726 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 9,870 deaths reported globally as of March 19, 2020.

On January 23, 2020, Wuhan - a city in China with 11 million residents - was forced to shut down both outbound and inbound traffic in an effort to contain the COVID-19 outbreak ahead of the Lunar New Year. However, it is estimated that more than five million people had already left the city before the lockdown (3), which has led to the rapid spread of COVID-19 within and beyond Wuhan.

In addition to population mobility and human-to-human contact, environmental factors can impact droplet transmission and survival of viruses (e.g., influenza) but have not yet been examined for this novel pathogen. Absolute humidity, defined as the water content in ambient air, as well as the temperature, have been found to be strong environmental determinants of other viral transmissions (4,5). For example, influenza viruses survive longer on surfaces or in droplets in cold and dry air increasing the likelihood of subsequent transmission. Thus, it is key to understand the effects of environmental factors on the ongoing outbreak to support decision-making pertaining to disease control. This is especially true for locations where the risk of transmission may have been underestimated, such as humid and warm places.

Our contribution:

We examine variability in environmental factors and transmission of COVID-19 across provinces and cities in China (and across selected other countries). We show that the observed spatial patterns of COVID-19 transmission cannot be explained by ambient temperature, absolute humidity or human mobility. Our findings do not support the hypothesis that high absolute humidity in warmer environments may limit the survival and transmission of this new virus.

Data and Methods

Epidemiological data.

To conduct our analysis, we collected epidemiological data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering website (6). Incidence data were collected from various sources, including the World Health Organization (WHO); U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); China CDC; European CDC; the Chinese National Health Center (NHC); as well as DXY, a Chinese website that aggregates NHC and local China CDC situation reports in near real-time. Daily cumulative confirmed incidence data were collected for each province in China from January 22, 2020 to February 26, 2020. We also obtained epidemiological data for other affected countries, including Iran, Italy, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea and 345 cities in China.

Estimation of a proxy for the reproductive number.

Based on the cumulative incidence data for each province, city or country, we estimated a proxy for the reproductive number R in a collection of 5-, 6- and 7-day intervals (7). R is a measure of potential disease transmissibility defined as the average number of people a case infects before it recovers or dies. Our proxy for R, designated as Rproxy, is a constant that maps cases occurring from time (t) to time (t+d) onto cases reported from time (t+d) to time (t+2d); where d is an approximation of the serial interval (i.e., the number of days between successive cases in a chain of disease transmission). For multiple time points, t, we obtained values of Rproxy(t,d), given by:

where C is the cumulative case count up to time t, and the values of d range from [5 to 7]. Our measure is considered only a proxy for R because it does not use details of the (currently imprecise definition of the) serial interval distribution, but instead, simply calculates the multiplicative increase in the number of incident cases over approximately one serial interval. Such proxies are at least approximately monotonically related to the true reproductive number and cross 1 when the true reproductive number crosses 1 (8), i.e. increases in our proxy typically signal increases in R. After computing these proxy values over a variety of subsequent moving time windows, for each serial interval (5, 6 and 7 days), a mean value was obtained and used as our estimated reproductive number R for each province, city, and country.

Time windows.

To characterize the temporal evolution of the COVID-19 outbreak, the reproductive number Rproxy was calculated for two different time periods. The first one, τ1, was from January 22, 2020 to February 8, 2020 and the second one, τ2, was from February 9, 2020 to February 26, 2020. In our study, the reproductive numbers computed on the first and second time periods are labeled R0τ1 and R0τ2, respectively.

Weather data.

All meteorological data for this study were taken from the ERA5 reanalysis, a state-of-the-art data product produced at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (9,10). ERA5 is generated by using a vast range of meteorological observations to constrain a physics-based numerical weather prediction model. This procedure, referred to by atmospheric scientists as data assimilation, yields a globally complete gridded data set including many different meteorological variables. Time resolution of ERA5 is quite high (1 hour) and it is also frequently updated (preliminary ERA5 data are available 5 days behind real time), making it useful for studies of rapidly evolving disease outbreaks. Since ERA5 is a relatively new data product, it has to our knowledge not previously been used for studies of meteorological effects on infectious disease in humans (11,12). However, a conceptually similar but much less sophisticated data product (the National Centers for Environmental Prediction-National Center for Atmospheric Research reanalysis, (13)) has been found useful for studies of influenza epidemics (5).

We obtained relevant ERA5 data at a spatial resolution of 0.25 degrees (~28 km at the equator). We represented weather conditions in each city of interest by those in the ERA5 grid box containing the city. Because we assumed that the majority of disease incidence for each province occurs in or near the capital due to increased population density in these areas, we chose to represent each province’s weather conditions by those in the ERA5 grid box containing the provincial capital. Of the five non-China countries we examined, one (Singapore) is a city-state but the other four have substantial geographic extents. For Iran, Italy, South Korea, and Japan we used ERA5 data appropriate for the cities of Qom, Codogno, Daegu, and Tokyo, respectively---the first three of these cities are in regions particularly affected by COVID-19, while the fourth is the national capital.

Near-surface air temperature, used in this study, is one of the standard ERA5 variables. Absolute humidity (more specifically, near-surface water vapor density) is not one of the standard ERA5 output variables. Instead, it must be computed from variables that are available, namely near-surface air temperature (T2) and near-surface dew point temperature (Td) (see supplementary material for more details). We produced hourly time series of temperature and humidity and then computed time mean absolute humidities and temperatures over January 17–31, 2020 and February 1–15, 2020, for comparison to τ1 and τ2 Rproxy data, respectively.

Human mobility data.

We obtained mobility data made publicly available by the Chinese Internet search engine Baidu (14). From the full origin-destination matrix for each day, we created a dataset to get the percentage of people traveling from Wuhan and going to the different Chinese provinces from January 1, 2020 to January 22, 2020 (i.e., before the mandated lockdown in Wuhan.)

Data Analysis.

Given the potential noise contained in the reported case counts, we tested the robustness of our findings by gradually removing provinces and cities for which their data was deemed too noisy or missing from our analysis. This was done in three subsequent filtering steps as follows. First, we included all provinces and cities where Rproxy could be properly calculated (i.e. enough cases were reported). Second, we removed provinces where mobility data was not available. Finally, we removed provinces and cities where the values of Rproxy were unrealistically high (due perhaps to reporting biases), specifically above 3. The latter filter was used to further remove potential noisy values that would affect our analysis and responding to the fact that the World Health Organization has estimated that R values range from 2 to 2.5. For country-level transmission, we did not conduct any statistical analysis due to the extremely noisy values of Rproxy.

Human mobility as a predictor of the reproductive number.

To disentangle if our reproductive number estimates could be explained by importation of cases from Wuhan, Hubei, alone; and if they could be interpreted as indicators of local transmission, we formulated a linear model with the local Rproxy as the response variable, and human mobility as a predictor at the province level. Specifically, we used mobility data before the closure of Wuhan (i.e from January 1, 2020 to January 22, 2020) to explain R0τ1.

where R0τ1(j) is the proxy for the reproductive number for the province j during the immediate time-period of two weeks after Wuhan’s lockdown; and Xmobility is the percentage of people traveling from Wuhan and residuals of the regression.

Relationship between reproductive number and temperature.

We used a Loess regression to visually represent the relationship between the reproductive number for each province and temperature. To identify the statistical relevance of this relationship we implemented a linear model using the log of the local reproductive number Rproxy as our response variable, and temperature as predictor. The linear model was computed for both time periods described above.

Depending on the time period explained, Rproxy corresponds to R0τl or R0τ2 for the province and the city-level; Xtemperature corresponds to the temperature for the first and second time periods.

Relationship between reproductive number and absolute humidity.

As for temperature, we conducted the same analysis for absolute humidity. The linear model was:

Where Xabs humidity corresponds to the absolute humidity for the first and second time periods.

Results

Reproductive number proxy.

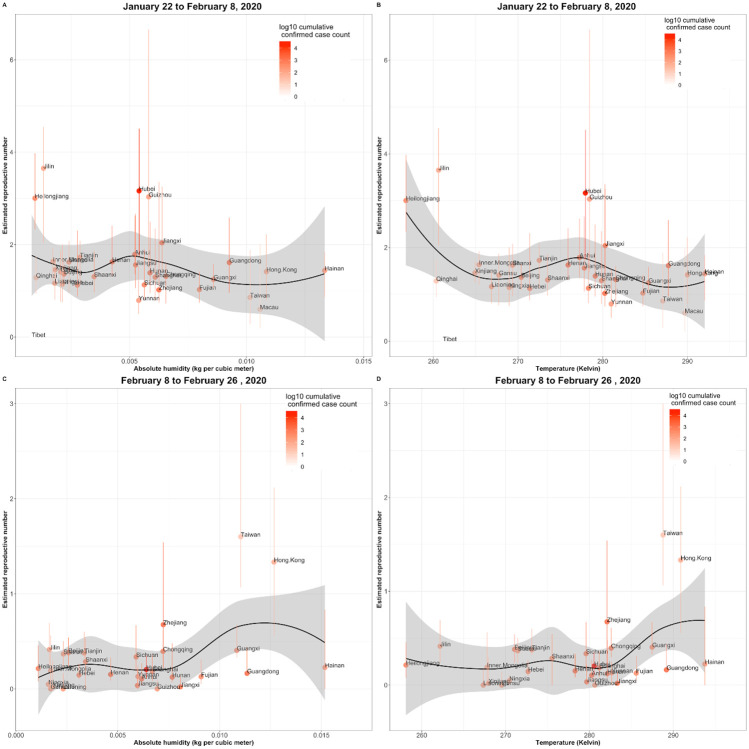

In both time periods, τ1 and τ2, our estimates of Rproxy for each province within China, appeared to be consistent across the range of serial intervals we analyzed (Figure 1). In the first time-period, most regions have a Rproxyestimate well above 1, signaling sustained disease transmission. Rproxy estimates across provinces decreased dramatically on the second time-period, many below 1, likely as a response to the multiple (non-pharmaceutical) interventions implemented by Chinese authorities.

Figure 1.

Estimated reproductive numbers Rproxy by province plotted as a function of absolute humidity or temperature for both time periods. 87% confidence intervals are displayed as vertical lines and were obtained from the collection of Rproxy calculated in subsequent time windows of length d for each location.

Data Analysis (Filtering).

In the first step of our analysis, the provinces of Tibet, Qinghai and Macau were removed due to the low number of reported COVID-19 cases there. Low number of cases (and multiple zeros) led to invalid calculations (NaN) of Rproxy. In the second step, we removed 3 provinces given that no mobility data were available: Tibet, Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia. Finally, 5 provinces were removed: Guizhou, Hubei, Heilongjiang, Jilin and Shandong given the unrealistically high value of their Rproxy (3.92, 3.19, 3.32, 3.57, and 4.45 respectively). At city level, 175 cities were removed due to the low number of cases (first filter) and 23 cities were removed because of the high value of their Rproxy (third filter). Finally, the values of Rproxy for countries are shown for reference: Iran (R0τ1 = 0 and R0τ2 = 34.00), Italy (R0τ1 = 0 and R0τ2 = 107.2), Singapore (R0τ1 = 1.85 and R0τ2 = 0.39), Japan (R0τ1 = 1.84 and R0τ2 = 2.70), and South Korea (R0τ1 = 3.11 and R0τ2 = 196.97).

Relationship with mobility.

Because Wuhan (provincial capital of Hubei) was the origin of the COVID-19 outbreak, and exported cases could only be calculated in the rest of the provinces, we excluded Hubei from our mobility analysis. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, identifying the influence of mobility on Rproxy can only be done after the third step of filtering. Human mobility (prior to Wuhan’s lockdown) did not appear associated with Rproxy across Chinese provinces during time-period τ1 (p-value = 0.93). However, in the same time-period, once we excluded Rproxy values above 3 (third step of filtering), mobility was found to be associated with Rproxy (p-value = 0.01).

Table 1.

Relationship between reproductive number for the first time period R0τ1, and mobility with the second step of filtering

| Number of observations | 28 |

| F-statistic | 0.009 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.927 |

| R-squared | 0.000 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.040 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.716 | 0.186 | 9.233 | 1.57*10−9 |

| Mobility | −0.01 | 0.139 | −0.092 | 0.927 |

Table 2.

Relationship between reproductive number for the first time period R0τ1, and mobility with the third step of filtering

| Number of observations | 23 |

| F-statistic | 7.528 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.012 |

| R-squared | 0.264 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.229 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.351 | 0.073 | 18.473 | 1.82*10−14 |

| Mobility | 0.139 | 0.051 | 2.744 | 0.012 |

Relationship with temperature.

After the first step of filtering, for the time-period τ1, temperature appeared to be associated with Rproxy at the 94% confidence level (Table 3). Specifically, temperature showed a negative relationship, indicating that higher temperatures appeared to have lower transmission. After the two additional steps of filtering, the association between temperature and Rproxy became weaker or non-significant (with p-values equal to 0.111 and 0.857 respectively; Tables 4 and 5). Weak to non-significant associations were observed when we conducted our analysis for the second time-period τ2, with p-values ranging from 0.118 to 0.700 (Tables 6, 7 and 8). At the city-level in China the temperature appeared to be associated to Rproxy for the first time-period and after removing cities with low number of cases (p-value = 0.01; Table S1). After removing Rproxy above 3, the temperature was no longer associated with Rproxy, with a p-value equal to 0.83 (Table S2).

Table 3.

Relationship between log(R0τ1) and temperature with the first step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 31 |

| F-statistic | 3.966 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.056 |

| R-squared | 0.120 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.090 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.553 | 2.050 | 2.220 | 0.034 |

| Temperature | −0.015 | 0.007 | −1.991 | 0.056 |

Table 4.

Relationship between log(R0τ1) and temperature with the second step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 28 |

| F-statistic | 2.725 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.1108 |

| R-squared | 0.095 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.060 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.369 | 2.348 | 1.861 | 0.074 |

| Temperature | −0.014 | 0.009 | −1.651 | 0.111 |

Table 5.

Relationship between log(R0τ1) and temperature with the third step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 23 |

| F-statistic | 0.033 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.857 |

| R-squared | 0.002 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.046 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.685 | 1.695 | 0.404 | 0.690 |

| Temperature | −0.001 | 0.006 | −0.183 | 0.857 |

Table 6.

Relationship between log(R0τ2) and temperature with the first step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 31 |

| F-statistic | 1.565 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.221 |

| R-squared | 0.051 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.018 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −10.03 | 6.795 | −1.476 | 0.151 |

| Temperature | 0.031 | 0.024 | 1.251 | 0.221 |

Table 7.

Relationship between log(R0τ2) and temperature with the second step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 28 |

| F-statistic | 0.152 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.700 |

| R-squared | 0.006 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.032 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −4.478 | 7.199 | −0.622 | 0.539 |

| Temperature | 0.010 | 0.026 | 0.389 | 0.700 |

Table 8.

Relationship between log(R0τ2) and temperature with the third step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 23 |

| F-statistic | 2.659 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.118 |

| R-squared | 0.112 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.070 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −13.12 | 6.96 | −1.886 | 0.073 |

| Temperature | 0.041 | 0.025 | 1.631 | 0.118 |

Relationship with absolute humidity.

In all steps of filtering at the province-level, and for both time periods, τ1 and τ2, absolute humidity was not associated to Rproxy, with p-values ranging between 0.161 and 0.922 (Tables 9 to 14). For cities, for time-period τ1, and after the first step of filtering, absolute humidity appeared to be associate with Rproxy with a p-value equal to 0.004 (Table S5). Specifically, absolute humidity showed a negative relationship, indicating that locations with higher absolute humidity experienced lower transmission. Nevertheless, after the third step of filtering, absolute humidity was not found to be associated with Rproxy, with a p-value equal to 0.64 (Table 6). For the second time period τ2, no associations were found either, with p-values equal to 0.95 and 0.87 after the two steps of filtering, respectively (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 9.

Relationship between log(R0τ1) and absolute humidity with the first step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 31 |

| F-statistic | 1.861 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.183 |

| R-squared | 0.060 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.028 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.618 | 0.125 | 4.945 | 2.95*10−5 |

| Absolute Humidity | −28.84 | 21.14 | −1.364 | 0.183 |

Table 14.

Relationship between log(R0τ2), and absolute humidity with the third step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 23 |

| F-statistic | 1.939 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.178 |

| R-squared | 0.085 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.041 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.20 | 0.355 | −6.211 | 3.67*10−6 |

| Absolute Humidity | 70.98 | 50.97 | 1.393 | 0.178 |

Discussion

Ambient temperature appears to be associated to COVID-19 transmission (as captured by our proxy of R) during the first time-period (January 22, 2020 to February 8, 2020) in both spatial resolutions and in the absence of any data filtering. Specifically, temperature showed a negative relationship, indicating that higher temperatures appeared to have lower COVID-19 transmission. These results were not robust to filtering techniques aimed at removing noisy values such as unrealistically high values of Rproxy (more than 3). In an effort to identify if transmission rates could be explained by the rate of case importations at the province-level, we analyzed if mobility from Wuhan to each province could explain the spatial variability of Rproxy during the first time-period. Our results showed no associations between mobility and Rproxy in the absence of data filtering but showed that Rproxy could be explained by mobility when removing values of Rproxy larger than 3. Finally, our analysis suggests that absolute humidity was not robustly associated with Rproxy, but these results need to be interpreted carefully given the monotonic functional relationship between humidity and temperature (Clausius-Clapeyron relation). In other words, if temperature were associated to COVID-19 transmission, very likely absolute humidity would play a role.

Limitations.

Our estimates of the observed Rproxy across locations were calculated using available and likely incomplete reported case count data, with date of reporting, rather than date of onset, which adds noise to the estimation. In addition, the relatively short time length of the current outbreak, combined with imperfect daily reporting practices, make our results vulnerable to changes as more data becomes available. We have assumed that travel limitations and other containment interventions have been implemented consistently across provinces and have had similar impacts (thus population mixing and contact rates are assumed to be comparable), and have ignored the fact that different places may have different reporting practices. Further improvements could incorporate data augmentation techniques that may be able to produce historical time series with likely estimates of case counts based on onset of disease rather than reporting dates. This, along with more detailed estimates of the serial interval distribution, could yield more realistic estimates of R. Finally, further experimental work needs to be conducted to better understand the mechanisms of transmission of COVID-19. Mechanistic understanding of transmission could lead to a coherent justification of our findings.

Conclusion.

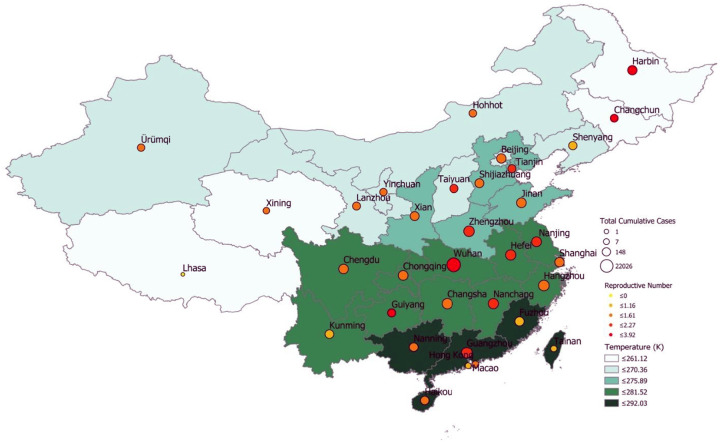

Sustained transmission and rapid growth of cases were observed over a range of temperatures and humidity conditions ranging from cold and dry provinces in China, such as Jilin and Heilongjiang, to tropical locations, such as Guangxi and Taiwan during the first time-period (τ1, from January 22nd to February 8th, 2020). Our results show that weather alone cannot explain, in a robust way, the variability of the reproductive number in Chinese provinces, cities or other countries. Moreover, drastic reductions in transmission were observed during the second half of February, likely due to the strict non-pharmaceutical interventions imposed across China. Further studies on the effects of environmental factors on COVID-19 will be possible as more data is collected in multiple affected geographies during this COVID-19 outbreak.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Temperature in each provincial capital vs. COVID-19 Rproxy estimate (calculated for the first time period). The size and color of each pin indicate cumulative cases per province and Rproxy range, respectively.

Table 10.

Relationship log(R0τ1) and absolute humidity with the second step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 28 |

| F-statistic | 0.784 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.384 |

| R-squared | 0.029 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.008 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.601 | 0.139 | 4.314 | 2.1*10−4 |

| Absolute Humidity | −22.25 | 25.132 | −0.885 | 0.384 |

Table 11.

Relationship between log(R0τ1), and absolute humidity with the third step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 23 |

| F-statistic | 0.010 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.922 |

| R-squared | 0.000 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.047 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.383 | 0.088 | 4.345 | 2.8*10−4 |

| Absolute Humidity | −1.501 | 15.130 | −0.099 | 0.922 |

Table 12.

Relationship between log(R0τ2) and absolute humidity with the first step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 31 |

| F-statistic | 2.072 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.161 |

| R-squared | 0.067 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.035 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.006 | 0.389 | −5.156 | 1.65*10−5 |

| Absolute Humidity | 79.68 | 55.35 | 1.439 | 0.161 |

Table 13.

Relationship between log(R0τ2) and absolute humidity with the second step of filtering.

| Number of observations | 28 |

| F-statistic | 0.192 |

| P-value (F-statistic) | 0.665 |

| R-squared | 0.007 |

| Adjusted R-squared | −0.031 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | T-Statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.827 | 0.404 | −4.520 | 1.19*10−4 |

| Absolute Humidity | 26.669 | 60.93 | 0.438 | 0.665 |

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Marc Lipsitch for helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

MS and CP were partially supported by the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM130668. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

References

- 1.Zhu N., et al. , A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 3.CGTN. Five million people left Wuhan before the lockdown, where did they go? Available from: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-01-27/5-million-people-left-Wuhan-before-the-lockdown-where-did-they-go--NACCu9wItW/index.html.

- 4.Barreca A.I. and Shimshack J.P., Absolute humidity, temperature, and influenza mortality: 30 years of county-level evidence from the United States. American journal of epidemiology, 2012. 176(suppl\_7): p. S114–S122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaman J., Goldstein E., and Lipsitch M., Absolute humidity and pandemic versus epidemic influenza. American journal of epidemiology, 2011. 173(2): p. 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johns Hopkins University, Center for Systems Science and Engineering website https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Li Q., et al. , Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallinga J. and Lipsitch M., 2007. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274(1609), pp.599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), 2017. ERA5: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS), accessed 22 February 2020 https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp/home

- 10.Hersbach H., et al. , 2019. Global reanalysis: goodbye ERA-Interim, hello ERA5. ECMWF Newsletter, 159, pp. 17–24, doi: 10.21957/vf291hehd7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban A., et al. Evaluation of the ERA5-based UTCI on mortality data in Europe. In Abstracts of the 2019 Annual Conference Of The International Society For Environmental Epidemiology, volume 3, October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerlini P., Silvestri L., Onofri A., and Farneselli M.. Validation of a regional agro meteorological network in Central Italy using ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis. In Geophysical Research Abstracts, volume 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalnay E., et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society,77(3):437–472, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Network Systems Science and Advanced Computing, 2020, “Baidu mobility data for January, 2020”, 10.18130/V3/YQLJ5W, University of Virginia Dataverse [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace John M. and Hobbs Peter V.. Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey, volume 92 of International Geophysics. Elsevier, second edition, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ECMWF. Part IV: Physical processes In IFS Documentation CY41R2, IFS Documentation. ECMWF, 2016. Available at https://www.ecmwf.int/node/16648, accessed 5 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.