Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 virus infects cells of the airway and lungs in humans causing the disease COVID-19. This disease is characterized by cough, shortness of breath, and in severe cases causes pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) which can be fatal. Bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and plasma from mild and severe cases of COVID-19 have been profiled using protein measurements and bulk and single cell RNA sequencing. Onset of pneumonia and ARDS can be rapid in COVID-19, suggesting a potential neuronal involvement in pathology and mortality. We sought to quantify how immune cells might interact with sensory innervation of the lung in COVID-19 using published data from patients, existing RNA sequencing datasets from human dorsal root ganglion neurons and other sources, and a genome-wide ligand-receptor pair database curated for pharmacological interactions relevant for neuro-immune interactions. Our findings reveal a landscape of ligand-receptor interactions in the lung caused by SARS-CoV-2 viral infection and point to potential interventions to reduce the burden of neurogenic inflammation in COVID-19 disease. In particular, our work highlights opportunities for clinical trials with existing or under development rheumatoid arthritis and other (e.g. CCL2, CCR5 or EGFR inhibitors) drugs to treat high risk or severe COVID-19 cases.

Introduction

The novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infects human airway and lung cells via entry through the ACE2 receptor (Tian et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020). This leads to a respiratory disease called COVID-19 that was declared a global pandemic in early 2020. The disease is characterized by fever, cough and shortness of breath but can progress to a severe disease state where patients develop pneumonia that can progress rapidly causing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Zhou et al., 2020a). This is potentially fatal without respiratory support. World-wide mortality from the disease is 1% or higher creating a dire need for therapeutics that can address this pandemic (Kupferschmidt and Cohen, 2020).

The airway and lung are innervated richly by sensory neurons that signal to the brain to induce cough and changes in respiration (Canning and Fischer, 2001; Canning, 2002; Canning and Spina, 2009; Canning, 2011). These sensory neurons also release efferent factors that can influence airway resistance, cause neurogenic inflammation, which can exacerbate pneumonia, and may contribute to ARDS. There is strong evidence that neurogenic factors play an important role in sepsis (Bryant et al., 2003; Devesa et al., 2011), which also occurs in many severe COVID-19 patients (Zhou et al., 2020a). Neurogenic inflammation is driven by the activation of sensory neurons, called nociceptors, which are responsible for the detection of damaging or potentially damaging stimuli (Woolf and Ma, 2007; Dubin and Patapoutian, 2010). These nociceptors innervate the lungs with origins in the thoracic dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and the nodose and jugular ganglia (Springall et al., 1987; Kummer et al., 1992; Canning, 2002; Canning and Spina, 2009). Nociceptors express a variety of receptors and channels that can detect factors released by the immune system (Woolf and Ma, 2007; Andratsch et al., 2009; Dubin and Patapoutian, 2010). Many, if not most, of these factors excite nociceptors, causing them to release specialized neuropeptides like calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) that cause vasodilation and plasma extravasation (Sann and Pierau, 1998) and also have direct effects on lung immune cells (Baral et al., 2018; Wallrapp et al., 2019). Research on pulmonary infection and cough has highlighted the critical role that nociceptors play in promotion of airway diseases (Hadley et al., 2014; Narula et al., 2014; Talbot et al., 2015; Bonvini et al., 2016; Baral et al., 2018; Garceau and Chauret, 2019; Ruhl et al., 2020).

The unprecedented scientific response to the SARS-CoV-2 driven pandemic has produced datasets that enable computational determination of probable intercellular signaling between nociceptors and immune signaling or response in the lung (Gordon et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020b; Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b). Because these interactions might be a crucial driver of disease severity, we set out to comprehensively catalog these interactions using our own RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets from human thoracic DRG (hDRG) (Ray et al., 2018; North et al., 2019). Using an interactome-based framework we have described previously (Wangzhou et al., 2020) to find high-value pharmacologically relevant targets, we identify new, potential intervention points to reduce disease burden in patients with existing or under-development drugs. A key finding emerging from the data is that certain interventions used or under development for rheumatic or neuropathic pain might be useful against COVID-19. This finding is consistent with independent data showing that lung inflammation causes a neuropathic phenotype in neurons innervating the lung (Kaelberer et al., 2020).

Supplementary tables can be found at our online repository, as Excel sheets: https://www.utdallas.edu/~prr105020/covid19/supptables.zip.

Results

Ligand - receptor interactome between COVID-19 patient BALF and hDRG

We first re-analyzed bulk RNA-seq data by mapping and quantifying relative gene abundance (in counts per million) from BALF (National Genomics Data Center accession number: PRJCA002326, https://bigd.big.ac.cn) of severe COVID-19 patients (Xiong et al., 2020b), compared to BALF (NCBI SRAdb project SRP230751, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) of healthy controls. Our control samples had highly consistent RNA profiles (Pearsons’ R = 0.9263). Differences between the two COVID-19 BALF samples can likely be attributed to variability of the immune response from patient to patient, as well as the lower sequencing depth of the samples, as even after pooling technical replicates for the COVID-19 patient samples we had ~ 12M and 7M sequenced reads. The two COVID-19 BALF samples were also found to contain SARS-CoV2 viral RNA reads confirming the presence of disease (Xiong et al., 2020b).

Out of 31,069 genes in the reference genome, we detected 18,507 and 18,855 genes in the control samples, and 13,973 and 13,545 genes in the COVID-19 patient samples; differences being primarily attributable to a decrease in sequencing depth for COVID-19 samples. Due to this and the fact that our goal was to identify potentially targetable protein interaction pathways in COVID-19 patients, we performed downstream analysis only on 1372 genes that were upregulated in the COVID-19 BALF samples (Supplementary Table 1).

Genes upregulated in the COVID-19 patient samples include a multitude of genes that recapitulate clinical characteristics, such as increased cytokine signaling causing a “cytokine storm” (including CCL2/3/4/7/8, CXCL1/2/6/8/28, CCL3L3, CCL4L2), hypoxia (HIF1A, HLF), and inflammasome and sepsis-related genes (IL1R1/2, IL5RA, IL33, IL31RA). BALF typically contains RNA profiles of immune cells in alveolar fluid, primarily lymphocytes and macrophages. Additionally, we found that upregulation of transcription factor genes in COVID-19 samples identifies transcription factors associated with alveolar cell types (EHF, PAX9, ELF3, GHRL2) and immune cells (RFX3, SOX5, TP63, HOPX) with functions including regulation of antiviral pathways (NR3C2), based on ARCHS4 database (Lachmann et al., 2018) and the Enrichr gene set enrichment analysis tool (Kuleshov et al., 2016) (Supplementary Table 2). This suggests that cellular distress and virus-driven cell lysis causes lung cell mRNA content to be detected in COVID-19 BALF samples. Immune cell markers like CD4, CD8, and CD68 were detected in COVID-19 samples, but were not consistently upregulated. Since we only quantified relative (and not absolute) abundance, this is possibly due to increased proportion of alveolar cell mRNA content in disease samples. However, lymphocyte markers CD24 and CD38 were upregulated in the COVID-19 BALF samples, which is also consistent with reports of lymphocyte induced apoptosis in COVID-19 (Huang et al., 2020a). These findings are congruent with reports of increased lactate dehydrogenase as a biomarker of COVID-19 severity wherein lactate dehydrogenase is a sign of pyroptosis - inflammasome driven programmed cell death (Rayamajhi et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020).

We were primarily interested in ligand to receptor signaling from immune cells in the lung to lung-innervating sensory neurons. For this purpose, we used our interactome framework (Ramilowski et al., 2015) to elucidate possible pharmacological interactions that may be associated with disease in COVID-19 samples. We focused first on ligands upregulated in the COVID-19 samples and receptors expressed in human thoracic DRG samples, which contain neurons that innervate the lungs (Springall et al., 1987; Kummer et al., 1992). We found that many receptors for cytokines identified as upregulated in COVID-19 patients including CCR2, CXCR2, CCR5, and CXCR10, and IL15RA were also expressed in hDRG suggesting a potential direct connection between these cytokines and sensory neuron activation in the lung (Table 1). We also noted increased EREG expression in COVID-19 samples, which is known to signal via the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) to sensitize nociceptors (Martin et al., 2017). Interestingly, there were a number of Eph ligand genes (EFNA1 and EFNA5) whose gene products are known to act via Eph receptors to modulate the activity of neurons as well as regulating connections between neurons (Henderson and Dalva, 2018). These Eph ligands were expressed de novo in disease samples. A complete list of the interactome featuring differentially increased ligands in BALF from COVID-19 samples can be seen in Supplementary Table 3, and expression profiles of the mouse orthologs in sensory neurons can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 1.

Interactome of BALF ligand to hDRG receptors. The average of gene abundances in the 2 COVID-19 samples, weighted by sequencing depth are shown here. Selected interactions are shown in the table. The full dataset is shown in Supplementary Table 3.

| BALF Ligand | BALF Samples (CPM) | Adjusted DEseq2 p-value | DRG receptor | DRG Samples (mean TPM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 | Control 2 | COVID-19 | ||||

| ASIP | 0.544 | 0.482 | 19.505 | 2.84E-22 | MC1R | 4.766 |

| CCL2 | 4.143 | 9.142 | 356.403 | 5.06E-18 | CCR1 | 13.768 |

| CCL2 | 4.143 | 9.142 | 356.403 | 5.06E-18 | CCR2 | 2.936 |

| CCL3 | 9.082 | 5.934 | 79.201 | 2.22E-14 | CCR1 | 13.768 |

| CCL3 | 9.082 | 5.934 | 79.201 | 2.22E-14 | CCR4 | 0.402 |

| CCL3 | 9.082 | 5.934 | 79.201 | 2.22E-14 | CCR5 | 2.898 |

| CCL3L3 | 1.883 | 1.027 | 49.648 | 3.73E-17 | CCR5 | 2.898 |

| CCL4 | 16.051 | 9.247 | 73.881 | 3.12E-05 | CCR1 | 13.768 |

| CCL4 | 16.051 | 9.247 | 73.881 | 3.12E-05 | CCR5 | 2.898 |

| CCL7 | 0.042 | 0.252 | 14.776 | 2.74E-09 | CCR1 | 13.768 |

| CCL7 | 0.042 | 0.252 | 14.776 | 2.74E-09 | CCR2 | 2.936 |

| CCL8 | 0.628 | 0.650 | 34.281 | 8.02E-16 | CCR1 | 13.768 |

| CCL8 | 0.628 | 0.650 | 34.281 | 8.02E-16 | CCR2 | 2.936 |

| CCL8 | 0.628 | 0.650 | 34.281 | 8.02E-16 | CCR5 | 2.898 |

| CFH | 2.679 | 1.195 | 18.914 | 6.23E-05 | ITGAM | 19.044 |

| EFNA1 | 0.063 | 0.189 | 27.779 | 6.63E-08 | EPHA2 | 19.566 |

| EFNA1 | 0.063 | 0.189 | 27.779 | 6.63E-08 | EPHA3 | 25.688 |

| EFNA1 | 0.063 | 0.189 | 27.779 | 6.63E-08 | EPHB1 | 4.968 |

| EFNA5 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 6.502 | 2.43E-09 | EPHB1 | 4.968 |

| EFNA5 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 6.502 | 2.43E-09 | EPHB2 | 7.152 |

| EREG | 4.478 | 1.677 | 54.968 | 4.68E-08 | EGFR | 77.492 |

| F13A1 | 1.549 | 2.390 | 104.025 | 4.47E-04 | ITGA4 | 14.674 |

| F13A1 | 1.549 | 2.390 | 104.025 | 4.47E-04 | ITGA9 | 22.324 |

| F13A1 | 1.549 | 2.390 | 104.025 | 4.47E-04 | ITGB1 | 385.262 |

| FGF13 | 0.565 | 0.524 | 40.191 | 2.16E-23 | SCN5A | 7.426 |

| FGF13 | 0.565 | 0.524 | 40.191 | 2.16E-23 | SCN8A | 79.656 |

| IL15 | 19.189 | 16.691 | 85.702 | 1.35E-04 | IL15RA | 4.618 |

| NTN1 | 0.732 | 0.608 | 9.457 | 1.92E-06 | DCC | 1.926 |

| PTN | 0.000 | 0.021 | 9.457 | 1.36E-12 | PLXNB2 | 111.694 |

| TFF1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 17.141 | 3.06E-13 | EGFR | 77.492 |

| TGFB2 | 0.105 | 0.189 | 8.866 | 4.35E-10 | TGFBR1 | 141.682 |

| TGFB2 | 0.105 | 0.189 | 8.866 | 4.35E-10 | TGFBR2 | 289.95 |

Previous work has shown that nociceptor-derived CGRP plays a key role in dampening the immune response to bacterial infection in the lung (Baral et al., 2018). Therefore, we also explored possible interaction points between sensory neurons that are likely to innervate the lung and receptors expressed in BALF samples from patients with COVID-19. Here, we identified a striking number of interactions between Eph ligands found in hDRG and receptors upregulated in COVID-19 BALF samples (Table 2). This is meaningful as there is emerging literature on an important role of the ephrin - Eph system in immunity (Darling and Lamb, 2019). Our data suggests potential bidirectional interactions between these receptors and ligands on sensory nerve endings and immune cells in the lung of COVID-19 patients. Another prominent interaction was with EGFR ligands and EGFR itself, again suggesting bidirectional interactions between neurons and immune cells in the lung in COVID-19. Finally, we also noted potential interactions between neurexins and neuroligins, which are also involved in junctions between neurons (Levinson and El-Husseini, 2005), suggesting that multiple types of mediators may be involved in remodeling nerve ending morphology within the lung driven by immune cell activation in COVID-19. Collectively, these neuron-derived ligands could potentially exacerbate lung inflammation in COVID-19 contributing to a positive feedback loop. A complete list of the interactome featuring differentially increased receptors in BALF from COVID-19 samples can be seen in Supplementary Table 5 and expression profiles of the mouse orthologs in sensory neurons can be found in Supplementary Table 6.

Table 2.

Interactome of hDRG ligand to BALF receptors. The average of gene abundances in the 2 COVID-19 samples, weighted by sequencing depth are shown here. Selected interactions are shown in the table. The full dataset is shown in Supplementary Table 5.

| DRG Ligand | DRG Samples (mean TPM) | BALF Receptor | BALF Samples (CPM) | Adjusted DEseq2 p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 | Control 2 | COVID-19 | ||||

| DCN | 1028.024 | EGFR | 0.167 | 0.356 | 33.690 | 3.61E-29 |

| EFNA1 | 14.852 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EFNA1 | 14.852 | EPHA5 | 1.214 | 1.447 | 14.185 | 8.30E-09 |

| EFNA1 | 14.852 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNA3 | 2.838 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EFNA3 | 2.838 | EPHA5 | 1.214 | 1.447 | 14.185 | 8.30E-09 |

| EFNA3 | 2.838 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNA4 | 5.342 | EPHA5 | 1.214 | 1.447 | 14.185 | 8.30E-09 |

| EFNA4 | 5.342 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNA5 | 19.364 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EFNA5 | 19.364 | EPHA5 | 1.214 | 1.447 | 14.185 | 8.30E-09 |

| EFNA5 | 19.364 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNB1 | 55.070 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EFNB1 | 55.070 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNB2 | 31.266 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EFNB2 | 31.266 | EPHA4 | 0.879 | 0.587 | 7.684 | 6.47E-05 |

| EFNB3 | 0.832 | EPHB1 | 0.356 | 0.587 | 27.779 | 1.87E-25 |

| EGF | 1.700 | ERBB4 | 0.188 | 0.776 | 66.789 | 2.38E-15 |

| EGF | 1.700 | EGFR | 0.167 | 0.356 | 33.690 | 3.61E-29 |

| EGF | 1.700 | ERBB3 | 0.314 | 0.776 | 7.684 | 1.91E-04 |

| EPGN | 0.786 | EGFR | 0.167 | 0.356 | 33.690 | 3.61E-29 |

| HBEGF | 16.790 | EGFR | 0.167 | 0.356 | 33.690 | 3.61E-29 |

| IGF1 | 30.036 | IGF1R | 6.131 | 7.758 | 38.418 | 5.53E-10 |

| LIF | 1.404 | LIFR | 0.105 | 0.356 | 15.367 | 6.10E-10 |

| NLGN1 | 20.258 | NRXN1 | 0.314 | 0.419 | 7.093 | 4.26E-07 |

| NLGN2 | 28.268 | NRXN1 | 0.314 | 0.419 | 7.093 | 4.26E-07 |

| NLGN3 | 66.420 | NRXN1 | 0.314 | 0.419 | 7.093 | 4.26E-07 |

| NLGN4X | 94.794 | NRXN1 | 0.314 | 0.419 | 7.093 | 4.26E-07 |

| NRG1 | 69.358 | ERBB4 | 0.188 | 0.776 | 66.789 | 2.38E-15 |

| NRG1 | 69.358 | ERBB3 | 0.314 | 0.776 | 7.684 | 1.91E-04 |

| NRG2 | 4.692 | ERBB4 | 0.188 | 0.776 | 66.789 | 2.38E-15 |

| NRG2 | 4.692 | ERBB3 | 0.314 | 0.776 | 7.684 | 1.91E-04 |

| NRG3 | 21.882 | ERBB4 | 0.188 | 0.776 | 66.789 | 2.38E-15 |

| NRG4 | 4.438 | ERBB4 | 0.188 | 0.776 | 66.789 | 2.38E-15 |

| NRG4 | 4.438 | EGFR | 0.167 | 0.356 | 33.690 | 3.61E-29 |

| NTN1 | 4.754 | DCC | 0.063 | 0.168 | 10.048 | 1.62E-11 |

| NTN4 | 28.880 | DCC | 0.063 | 0.168 | 10.048 | 1.62E-11 |

Interactome of curated COVID-19 ligands from the literature to hDRG receptors

The immune response is tuned by both harnessing specific cell types (by chemotaxis and other mechanisms), and by modulating molecular profiles of these cell types (by transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational and post-translational mechanisms). While our interactome identification from the BALF bulk RNA-seq is a starting point for identifying neuro-immune interactions in COVID-19 patient lungs, bulk RNA sequencing has limitations and other approaches are also being used to characterize the immune response in this disease. We therefore studied the emerging COVID-19 literature for studies where raw datasets were not publicly available, but the studies provided gene or protein sets that were associated with clinical outcomes or pathologies. In addition to the Xiong et al study (Xiong et al., 2020b), we integrated gene and protein lists from sources that included BALF single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), blood protein levels and immune cell profiles from COVID-19 patients (Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020b). This effort identified more than 150 genes. Since a large proportion of these were ligands, we constructed a unidirectional ligand-receptor interactome from these gene products to hDRG expressed receptors based on our previous RNA-seq experiments (North et al., 2019). These findings were consistent with the interactome generated from BALF samples from COVID19 patients with prominent interactions for cytokines, chemokines and other inflammatory molecules (Supplementary Table 7). These included CCL2/3/4/5/7/10, IL1 and TNFas well as anti-inflammatory molecules IL10 and TGFB1 and TGFB2. These finding implicate the potential off-label utility of anti-rheumatoid arthritis drugs that target TNF (infliximab or etanercept) or IL1 (anakinra) as well as EGFR inhibitors such as cetuximab for interfering with neuro-immune interactions in COVID-19.

Identification of putative mammalian nociceptor expression

Using only deeply sequenced thoracic hDRG bulk RNA-sequencing as a proxy for human nociceptor expression can generate both false positives and false negatives. Bulk hDRG sequencing libraries incorporate mRNA from not just sensory neurons, but also from glial, immune and vascular cells, leading to the possibility of false positives. Additionally, many lung innervating nociceptors are from the nodose or jugular ganglia so our dataset from thoracic hDRG may not represent the full possibility of receptors or ligands that could contribute to lung physiology from sensory afferents. Unfortunately, no sequencing data is available from the human nodose or jugular ganglia. To predict which of the hDRG-expressed ligands or receptors are likely present in human nociceptors, we integrated several mouse datasets. We used FACS sorted neuronally enriched mouse DRG cell pool RNA-seq (Liang et al., 2019), and mouse DRG scRNA-seq data (Usoskin et al., 2015). We additionally included two datasets for gene expression in the mouse jugular-nodose complex (JNC), including the Kupari et al scRNA-seq dataset (Kupari et al., 2019) and a study using bulk RNA-seq to study gene expression changes in the JNC following lung inflammation with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Kaelberer et al., 2020). From this analysis (Supplementary Tables 3–6) we found clear evidence for nociceptor expression of EFNA1, EFNB1 and EFNB2 suggesting the ephrin signaling is likely to influence lung nociceptors. The same was true for neuroligin genes NLGN2 and NLGN3. Likewise, we found strong evidence for cytokine receptor gene expression in nociceptors, most notably CCR2, LIF (which was specific to the nonpeptidergic population) and IL15RA but also ITGAM and ITGA9. As mentioned above, EGFR ligands were strongly induced in COVID-19 patients. The ERBB2 gene was strongly expressed in single cell and sorted neuron samples but the EGFR gene was sparsely expressed or not detected. However, EGFR was increased in nerve injury samples suggesting that this receptor is induced in nociceptors after injury. Since ERBB2 encodes a receptor that acts in concert with EGFR, more work is needed to better understand how this receptor may function to modulate the activity of lung nociceptors.

Possible pharmacological intervention points for existing or under-development drugs

A major focus of current research into SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 is identification of potential therapeutics. From that perspective, a recent paper described a protein-protein interactome of SARS-CoV-2 proteins with the human proteome and identified druggable interaction points (Gordon et al., 2020). A target identified from that paper was the RNA binding protein, eIF4E, the phosphorylation of which has been implicated in coronavirus replication (Banerjee et al., 2002; Mizutani et al., 2004) and the suppression of anti-viral responses (Herdy et al., 2012). Previous work suggests that eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK, a druggable target identified by Gordon et al. (2020), plays a key role in regulating the excitability of nociceptors (Moy et al., 2017; Megat et al., 2019; Shiers et al., 2020) and also regulates the translation of many cytokines and chemokines (Furic et al., 2010; Herdy et al., 2012; Amorim et al., 2018). Based on this, we intersected differentially expressed BALF ligand and receptor genes in COVID-19 samples with mRNAs known to be regulated by eIF4E phosphorylation from previous studies (Furic et al., 2010; Aguilar-Valles et al., 2018; Amorim et al., 2018).

We found that 8 inflammatory mediators upregulated in the BALF of COVID-19 patients were reduced in vitro and/or in the brain of animals lacking eIF4E phosphorylation (Table 3). CCL2, which is among the most highly upregulated chemokines in COVID-19 patients, is one example. CCL2 impairs virus clearance, reduces macrophage maturation, and increases lethality after coronavirus infection (Held et al., 2004; Trujillo et al., 2013). Furthermore, CCL2 levels in the nasal aspirate of asthmatic individuals are correlated with severe respiratory symptoms following viral infection (Lewis et al., 2012). Upregulation of CCL2 following SARS-CoV (the virus that caused the first SARS epidemic) infection is mediated by Ras-ERK pathway that is activated by ACE2 signaling (Chen et al., 2010). A downstream target of the Ras-ERK pathway is MNK, which in turn phosphorylates eIF4E to influence mRNA translation. It is possible that the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which also enters cells through ACE2, enhances the production of CCL2 via MNK-eIF4E signaling. Hence, eFT508 (also known as Tomivosertib), a MNK1/2 inhibitor currently undergoing clinical trials (Reich et al., 2018), may prove beneficial against COVID-19.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes in BALF of COVID-19 patients that are known to be regulated by MNK - eIF4E signaling based on studies in eIF4ES209A-knock-in mutant cells and animals. These knock-in animals and cells are null mutants for eIF4E phosphorylation.

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | COVID19 BALF | eIF4ES209A-KI vs. WT | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | ||||

| CCL2 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 | ↑ | ↓ | (Furic et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2020a; Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b) |

| CCL7 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 7 | ↑ | ↓ | (Furic et al., 2010; Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b) |

| CD14 | Cluster of differentiation 14 | ↑ | ↓ | (Amorim et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020) |

| CYP1B1 | Cytochrome P450 1B1 | ↑ | ↓ | (Furic et al., 2010; Liao et al., 2020) |

| NCF1 | Neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 | ↑ | ↓ | (Amorim et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020) |

| NFKBIA | NFKB inhibitor alpha | ↑ | ↓ | (Furic et al., 2010; Liao et al., 2020) |

| S100A9 | S100 calcium-binding protein A9 | ↑ | ↓ | (Amorim et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020) |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | ↑ | ↓ | (Amorim et al., 2018; Xiong et al., 2020a) |

| Upregulated | ||||

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | ↑ | ↑ | (Aguilar-Valles et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020a) |

We also identified potential therapeutics for COVID-19 by intersecting the interactomes generated here with the DGIdb database (Cotto et al., 2018). We identified 144 gene products with characterized antagonists, inhibitors, blockers or modulators in this curated database (a selection of these are shown in Table 4, full dataset in Supplementary Table 8). This database highlights the potential for targeting cytokines and chemokines, such as CCL2, the CCR2 receptor and/or the EGFR receptor in COVID-19. It also reveals several drugs that interact with ephrin - EphB signaling that may have promise if structural remodeling of lung afferent endings contributes to COVID-19 pathology. Interestingly, the NMDA receptor 2B (GRIN2B) subunit was revealed in this list, which can be targeted with ketamine and other drugs. The corresponding gene GRIN2B was strongly induced in BALF samples of COVID-19 samples. The NMDA receptor is activated by glutamate, which is released by sensory neurons at their peripheral terminals. NMDA receptor activity and localization is strongly influenced by EphB receptors (Hanamura et al., 2017; Henderson and Dalva, 2018), which were also dramatically increased in COVID-19 BALF samples. These findings reveal a potential new pathway for sensory modulation of lung pathophysiology involving glutamate from sensory afferents acting on NMDA receptors expressed by resident cells in the lung.

Table 4.

Drug candidates identified for key targets found in this study. Mechanism key: I, inhibitor; A, agonist; AB, antibody; AM, allosteric modulator; Ant, antagonist; B, binder; CB, channel blocker; S, suppressor. Full table is shown in Supplementary Table 8.

| Gene product | Drug (mechanism) |

|---|---|

| CCL2 | Carlumab (I), CHEMBL134074 (I), danazol (I) |

| CCR2 | AZD2423 (AM, A), CCX140 (Ant), cenicriviroc (Ant), CHEMBL134074 (Ant), CHEMBL1593104 (Ant), CHEMBL337246 (Ant), CHEMBL432713 (Ant), fulvestrant (Ant), meglitinide (Ant), mibefradil (AM), MLN-1202 (Ant), PF-04634817 (Ant), phenprocoumon (Ant), picrotoxinin (Ant) |

| CCR4 | Plerixafor (Ant) |

| CCR5 | Ancriviroc (Ant), aplaviroc (Ant), aplaviroc hydrochloride (Ant), AZD5672 (Ant), cenicriviroc (Ant), CHEMBL1196395 (Ant), CHEMBL41275 (Ant), INCB-9471 (Ant), maraviroc (Ant), PF-04634817 (Ant), phenprocoumon (Ant), PRO-140 (AB, A), vicriviroc (Ant), vicriviroc maleate (Ant) |

| CCR9 | Hydralazine (Ant), MLN3126 (Ant), verecimon (Ant, AM) |

| EGFR | AC-480 (I), acalabrutinib (I), AEE-788 (I), afatinib dimaleate (I), afatinib (I), allitinib (I), AZD-4769 (I), BGB-283 (I), BMS-690514 (I), brigatinib (I), canertinib dihydrochloride (I), canertinib (I), CEP-32496 (I), cetuximab (Ant, AB, I), CHEMBL1081312 (I), CHEMBL1229592 (I), CHEMBL174426 (I), CHEMBL1951415 (I), CHEMBL2141478 (I), CHEMBL306380 (I), CHEMBL387187 (I), CHEMBL53753 (I), CHEMBL56543 (I), CUDC-101 (I), dacomitinib hydrate (I), dacomitinib (I), dovitinib (I), EGF816 (I), epitinib (I), erlotinib (Ant, I), erlotinib hydrochloride (I), falnidamol (I), felypressin (I), gefitinib (Ant, I), HM-61713 (I), ibrutinib (I) icotinib (I, A), JNJ-26483327 (I), lapatinib ditosylate (I), lapatinib (I, A), mab-425 (I), matuzumab (I), momelotinib (I), MP-412 (I), mubritinib (I), naquotinib (I), necitumumab (AB, Ant, I), neratinib (I), olmutinib (I, A), orantinib (I), osimertinib (I), osimertinib mesylate (I), panitumumab (A, S, AB, I), PD-0166285 (I), pelitinib (I), PKI-166 (I), poziotinib (I), puquitinib (I), pyrotinib (I), RG-7160 (Ant), rociletinib (I), S-222611 (I), sapitinib (I), SB-243213 (I), simotinib (I), TAK-285 (I), tesevatinib (I), theliatinib (I), tyrphostin AG-1478 (I), vandetanib (I), varlitinib (I), zalutumumab (AB, A) |

| EPHB1 | Vandetanib (I) |

| EPHB2 | Vandetanib (I) |

| GRIN2B | Acamprosate calcium (Ant), amantadine hydrochloride (CB, A), AV-101 (Ant), AZD8108 (Ant), besonprodil (Ant), CERC-301 (Ant), CGP-37849 (Ant), CHEMBL1184349 (CB), CHEMBL173031 (Ant), CHEMBL191838 (Ant), CHEMBL22304 (Ant), CHEMBL273636 (Ant), CHEMBL287327 (Ant), CHEMBL31741 (Ant), CHEMBL50267 (Ant), CNS-5161 (CB), conantokin G (Ant), delucemine (Ant), dizocilpine (CB), EVT-101 (Ant), felbamate (Ant), GW468816 (Ant), ifenprodil (Ant), Indantadol (Ant), ketamine (CB), lanicemine (CB), magnesium (CB), mesoridazine (Ant), modafinil (Ant), neramexane mesylate (Ant), orphenadrine chloride (Ant), orphenadrine citrate (Ant), phencyclidine (CB), radiprodil (Ant), ralfinamide (Ant), selfotel (Ant), tenocyclidine (Ant), traxoprodil (Ant) |

| IL15 | AMG-714 (I, AB) |

| IL1B | Canakinumab (I, B, AB), gallium nitrate (Ant, I), ibudilast (I), rilonacept (I, B) |

| IL1R1 | AMG-108 (Ant), anakinra (Ant, I), oxandrolone (Ant) |

| IL2RA | Basiliximab (AB, I), daclizumab (AB, I), inolimomab (Ant) |

| IL6 | Asian ginseng (Ant), Clazakizumab (I), elsilimomab (I), ibudilast (I), olokizumab (I), PF-04236921 (I), siltuximab (Ant, AB I), sirukumab (I) |

| IL6R | SA237 (Ant), sarilumab (Ant), tocilizumab (AB, I) |

| TLR4 | CHEMBL225157 (Ant), eritoran tetrasodium (Ant) |

| TLR7 | Hydroxychloroquine (Ant), hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Ant), motesanib (Ant) |

| TLR9 | Hydroxychloroquine (Ant), hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Ant), motesanib (Ant) |

| TNF | Adalimumab (AB, I), afelimomab (I), ajulemic acid (I), AZ-9773 (I), certolizumab pegol (neutralizer, AB, I), CHEMBL219629 (I), delmitide (I), etanercept (AB, I), golimumab (AB, I), inamrinone (I), infliximab (I, AB), lenalidomide (I), lenercept (I), nerelimomab (I), onercept (I), ortataxel (I), ozoralizumab (I), pegsunercept (I), pirfenidone (I), placulumab (I), pomalidomide (I), talactoferrin alfa (I), urapidil (I) |

Discussion

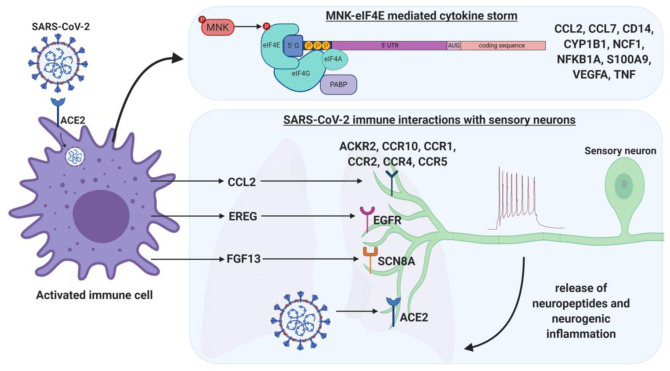

Our work identifies potential interactions that may be critical drivers of disease severity in COVID-19. Some of these, such as CCL2, epiregulin acting via the EGFR receptor and TNFa can be inhibited with drugs in late stage development (e.g. CCL2) or existing therapeutics (e.g. EGFR or TNFa) (summarized in Figure 1). All 3 of these targets have been implicated in increasing nociceptor excitability (Hensellek et al., 2007; Belkouch et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2017). It may be necessary to target multiple pathways to overcome the severe respiratory phenotype produced by this disease. To that end, MNK inhibitors, which were also identified by Gordon et al. (Gordon et al., 2020) may be particularly useful because they have an effect on coronavirus replication in murine models (Banerjee et al., 2002), interfere with the translation of chemokine and cytokines implicated in COVID-19 and reduce excitability of nociceptors (Moy et al., 2017; Megat et al., 2019) that may be driving neurogenic inflammation in the disease. Clinical trials are obviously needed to test these hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Our work identifies that: 1) Several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are upregulated in the COVID-19 BALF samples that are known to be translationally-regulated via MNK-eIF4E signaling. This offers a unique opportunity to disrupt activity of many inflammatory proteins via MNK inhibitors. 2) Many upregulated COVID-19 inflammatory mediators interact with receptors potentially expressed on thoracic sensory neurons that innervate the lung. Activation of these sensory neurons may cause them to release neuropeptides back into the lung environment to cause vasodilation, immune cell recruitment, neurogenic inflammation, and potentially even pain upon breathing. 3) It is currently unknown if ACE2, the receptor through which SARS-CoV-2 can infiltrate cells, is expressed in sensory neurons.

There are important caveats to our work. First, the interactomes we have built are based largely on data from a limited number of patients. Similar results have been found across studies (Huang et al., 2020b; Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020b), but there is an obvious need for additional sequencing on lung immune cells from patients with mild and severe COVID-19. The availability of such data, either bulk RNA-seq or single cell RNA-seq would greatly improve our ability to hone in on more specific targets.

Another important caveat is that the directionality of the influence of nociceptor-released factors on lung immunity and COVID-19 disease state is not currently clear. Some studies on sepsis, which occurs in severe COVID-19 patients, have shown that nociceptors promote mortality in sepsis (Bryant et al., 2003) but others show that TRPV1-positive nociceptors are protective against mortality in sepsis (Guptill et al., 2011). In the case of lung infection by bacteria, CGRP, which is released by nociceptors, has been shown to play a protective role by limiting immune reaction within the lung (Baral et al., 2018). Little work has been done to understand how viral infections and sensory neurons interact to promote or suppress the immune response. However, the existing literature on sensory innervation of the airway and lung with bacterial pathogens suggests that sensory afferents can have detrimental and beneficial effects depending on the context (Chiu et al., 2012; Chavan et al., 2018; Ruhl et al., 2020). We have interpreted our interactome findings under the assumption that neurogenic responses may worsen the disease state in COVID-19, potentially leading to ARDS and fatality, but without perturbational animal model studies or additional human clinical data we cannot rule out the possibility that a subset of the interactome mitigates the disease state. However, recent findings that lung inflammation creates a neuropathic-like state in lung-innervating nociceptors (Kaelberer et al., 2020) suggests that our hypothesis of neurogenic response worsening the disease is supported by available data.

A third caveat is the fact that we have predicted neuro-immune interactions based on the assumption that lung and airway-innervating sensory neuronal transcriptomes remain mostly unchanged after infection. It is formally possible that sensory neurons could express ACE2 allowing viral infection of these cells, but available datasets are unable to clarify this question. A bigger potential issue is that lung inflammation clearly alters the transcriptome of neurons that innervate the lung in rodents (Kaelberer et al., 2020), but the time-course and magnitude of this effect at the single cell level has not been studied previously, and little is known about evolutionary conservation of the transcriptional response between humans and rodents. These are obviously important areas of research that need to be explored in future studies.

In conclusion, our work identifies several new potential therapeutics for COVID-19 treatment. Based on the currently available evidence, we suggest further investigation of MNK and EGFR inhibitors, TNFa sequestering treatments and CCL2 inhibitors, alone or in combination, for the treatment of severe COVID-19.

Methods

Study Approval

IRB approval for RNA sequencing from human DRG samples was provided by University of Texas at Dallas as described previously (North et al., 2019). Other datasets used here were based on analysis from datasets described in published studies from other groups.

Data Sources

Human thoracic DRG data was described in (North et al., 2019). Data for the curated COVID-19 interactome were obtained from (Huang et al., 2020b; Liao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2020a), with BALF RNA-seq data from COVID-19 patients (National Genomics Data Center sample ids CRR119894–7, https://bigd.big.ac.cn/bioproject/browse/PRJCA002326) obtained from (Xiong et al., 2020b). BALF control data was obtained from control RNA-seq samples (Michalovich et al., 2019) in healthy patients (SRAdb sample ids SRR10571724, and SRR10571732, https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/?study=SRP230751).

Mouse DRG single cell sequencing data were obtained from mouse DRG (Usoskin et al., 2015) and JNC (Kupari et al., 2019). Mouse bulk RNA-sequencing datasets were obtained from sorted neuronal cell pools from the DRG (Liang et al., 2019) and whole tissue RNA-seq from the JNC complex before and after LPS injury (Kaelberer et al., 2020).

Three previous studies of eIF4E phosphorylation (Furic et al., 2010; Aguilar-Valles et al., 2018; Amorim et al., 2018) were used to identify the set of genes which can be potentially affected by MNK inhibition. The DGIdb database was used to identify known drugs (Cotto et al., 2018) that target proteins in our identified interactomes.

The interactome database is described in detail in our previous work (Wangzhou et al., 2020).

Re-analysis of BALF RNA-sequencing data

BALF RNA-seq data (Xiong et al., 2020b) was compared with control RNA-seq by mapping RNA-seq reads to the reference genome Refseq hg38 and reference transcriptome Gencode v33 (Frankish et al., 2019) using the STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013). Read counts per gene was then summarized for each sample by HT-Seq Count (Anders et al., 2015). Replicates from each COVID-19 patient were pooled to increase sequencing depth. Due to the higher sequencing depth of the control samples (over 40 million reads), compared to the COVID-19 samples (~ 7 and 12 million reads after pooling (Xiong et al., 2020b)), and due to specific interest in finding therapeutic targets, only genes identified as differentially expressed and increased in relative abundance in COVID-19 samples were further analyzed. Low replicate numbers cause difficulty in estimation of dispersion, and lower sequencing depth increases sampling variance in the data. To conservatively identify differentially expressed genes, analysis was performed using two well established differential expression analysis tools - edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010) and DEseq2 (Love et al., 2014), both of which model gene counts as negative binomial distributions and estimate mean and dispersion parameters from the data. edgeR moderates estimated gene count dispersions towards a common sample-specific estimate for all genes. DEseq2 models dispersion as a function of the expression level. Genes that have an adjusted p-value of < 0.001 and log2 fold change > 2.0 were used to identify differentially expressed gene sets for each tool. Differentially expressed gene sets from both tools were intersected to identify genes that are differentially expressed in both models, and only genes with read frequency > 1 in 200,000 genic reads for COVID-19 samples were retained to reduce potential effects of sampling variance. For differentially expressed genes, we provide relative abundance in the form of counts per million mapped genic reads (CPM) for each sample, as well as p-values and multiple testing adjusted p-values for both tools (Supplementary Table 1). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using the Enrichr framework, and limited to gene - transcription factor co-expression modules with 50 or more genes (Supplementary Table 2).

Creation of a ligand receptor signaling interactome database

Ramilowski et al. (Ramilowski et al., 2015) described 2557 pairs of ligand-receptor interactions that were used to populate the initial interactome database. However, hundreds of known ligands and receptors were missing from this resource. In order to curate a more complete ligand-receptor list, we collected gene lists from gene family and ontology databases HUGO (Yates et al., 2017) and GO (Carbon et al., 2009). Genes corresponding to the GO terms of cell adhesion molecules (CAM), G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), growth factor, ion channels, neuropeptides, nuclear receptors, and receptor kinases were tabulated. Based on a database (Szklarczyk et al., 2019) and the literature, corresponding receptors or ligands for these additional genes were identified and added to the list of ligand-receptor pairs. A total of 3098 pairs of ligand-receptor interactions were used in the interactome analysis for all possible ligand-receptor interactions (Wangzhou et al., 2020).

Not all ligands and receptors are encoded as genes, so we included some additional records in our database, such as enzymes known to synthesize ligands and paired with the corresponding receptor. Additionally, some other interactions were include that do not have a traditional ligand - receptor relationship. In these cases, the gene for the upstream signaling molecule was analyzed in lieu of the ligand, and the gene for the downstream signaling molecule in lieu of the receptor. The entire interactome database is described in detail in (Wangzhou et al., 2020).

Based on gene expression in BALF and human DRG samples, the interactome extends to thousands of candidate ligand-receptor pairs. While many of these signaling interactions are likely involved in the immune response of COVID-19, we chose to focus on pairs where the ligand or receptor was shown to be differentially increased or discriminative marker for cell types with differentially increased proportions in the immune response since these are more likely to be successful points of therapeutic intervention. Thus, we filtered the candidate interactome based on the list of differentially expressed genes we obtained from the literature and re-analysis of COVID-19 BALF data (Supplementary Tables 3, 5 and 7). Potentially relevant gene product - drug interactions (inhibitor, antagonist or blocker) based on these interactomes were mined from the dgiDB database (Supplementary Table 8).

Finally, we decided to tabulate these interactions with the ability to rank them using four metrics reported in Supplementary Tables. Two of these help rank immune genes : mean expression level in COVID-19 samples, and degree of differential expression (fold change) in COVID-19 versus control BALF (Supplementary Tables 3 and 5). These are likely to identify signaling pathways with the greatest frequency of ligand-receptor interaction, or maximal changes in the frequency or intensity of such interactions. Two other metrics help rank neuronal genes: gene expression levels in sorted mouse DRG neuron datasets (Liang et al., 2019) and in mouse DRG neuron scRNA-seq datasets (Usoskin et al., 2015), and degree of differential expression (log fold change) in LPS based injury models of mouse airway-innervating neurons (Kaelberer et al., 2020) (Supplementary Tables 4 and 6). These are likely to identify neuronally expressed genes, as well as genes involved in ARDS in mammalian lungs. The directionality of changes in the LPS mouse injury model may not necessarily be consistent with changes in COVID-19 molecular changes, but are likely to be indicative of genes involved in neuroinflammation in mammalian lungs.

In order to identify genes that were stably expressed in the hDRG, only protein interactions where the corresponding neuronal gene expression in the hDRG was >= 0.15 TPM (as reported in North et al., 2019) were retained. To quantify relative gene abundances in (Liang et al., 2019), reported coding gene expressions were renormalized to TPMs across all samples, and samples having a clear bimodal distribution of TPMs were retained for further analysis and quantile normalized, of which the FACS-sorted neuronal datasets are used in our study for integrative analysis. Reported gene abundances in (Kaelberer et al., 2020) were renormalized to a million. In the (Usoskin et al., 2015) dataset, the reported fraction of cells for each neuronal subpopulation (where a gene is detected) was used. To calculate a similar metric in the (Kupari et al., 2019) dataset, two steps were performed. Based on the reported clusterings of the cell types in the JNC, the four most distinct groups of neuronal subpopulations (Kupari et al., 2019), comprising jugular ganglial neuronal subpopulations 1–3 and 4–6, and nodose ganglial neuronal subpopulations 1–11 and 12–18 were used. To calculate the fraction of cells where genes were detected in each of these four groups, cells in the lowest quartile (bottom 25th percentile) of the cell population with respect to library diversity (number of unique molecular identifiers or UMI < 23,385) were discarded.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH grant NS065926 and NS115441 to TJP.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest, except TJP who is a co-founder and board member of 4E Therapeutics.

References

- Aguilar-Valles A, Haji N, De Gregorio D, Matta-Camacho E, Eslamizade MJ, Popic J, Sharma V, Cao R, Rummel C, Tanti A, Wiebe S, Nunez N, Comai S, Nadon R, Luheshi G, Mechawar N, Turecki G, Lacaille J-C, Gobbi G, Sonenberg N (2018) Translational control of depression-like behavior via phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E. Nature Communications 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim IS, Kedia S, Kouloulia S, Simbriger K, Gantois I, Jafarnejad SM, Li Y, Kampaite A, Pooters T, Romano N, Gkogkas CG (2018) Loss of eIF4E Phosphorylation Engenders Depression-like Behaviors via Selective mRNA Translation. The Journal of Neuroscience 38:2118–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31:166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andratsch M, Mair N, Constantin CE, Scherbakov N, Benetti C, Quarta S, Vogl C, Sailer CA, Uceyler N, Brockhaus J, Martini R, Sommer C, Zeilhofer HU, Muller W, Kuner R, Davis JB, Rose-John S, Kress M (2009) A key role for gp130 expressed on peripheral sensory nerves in pathological pain. J Neurosci 29:13473–13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Narayanan K, Mizutani T, Makino S (2002) Murine coronavirus replication-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation promotes interleukin-6 production and virus replication in cultured cells. Journal of virology 76:5937–5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral P, Umans BD, Li L, Wallrapp A, Bist M, Kirschbaum T, Wei Y, Zhou Y, Kuchroo VK, Burkett PR, Yipp BG, Liberles SD, Chiu IM (2018) Nociceptor sensory neurons suppress neutrophil and gammadelta T cell responses in bacterial lung infections and lethal pneumonia. Nat Med 24:417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkouch M, Dansereau MA, Reaux-Le Goazigo A, Van Steenwinckel J, Beaudet N, Chraibi A, Melik-Parsadaniantz S, Sarret P (2011) The chemokine CCL2 increases Nav1.8 sodium channel activity in primary sensory neurons through a Gbetagamma-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 31:18381–18390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvini SJ, Birrell MA, Grace MS, Maher SA, Adcock JJ, Wortley MA, Dubuis E, Ching YM, Ford AP, Shala F, Miralpeix M, Tarrason G, Smith JA, Belvisi MG (2016) Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 4 and airway sensory afferent activation: Role of adenosine triphosphate. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138:249–261 e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant P, Shumate M, Yumet G, Lang CH, Vary TC, Cooney RN (2003) Capsaicin-sensitive nerves regulate the metabolic response to abdominal sepsis. J Surg Res 112:152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ (2002) Neurology of allergic inflammation and rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ (2011) Functional implications of the multiple afferent pathways regulating cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 24:295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ, Fischer A (2001) Neural regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. Respir Physiol 125:113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ, Spina D (2009) Sensory nerves and airway irritability. Handb Exp Pharmacol:139–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon S, Ireland A, Mungall CJ, Shu S, Marshall B, Lewis S, Ami GOH, Web Presence Working G (2009) AmiGO: online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 25:288–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan SS, Ma P, Chiu IM (2018) Neuro-immune interactions in inflammation and host defense: Implications for transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 18:556–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, Wang T, Zhang X, Chen H, Yu H, Zhang X, Zhang M, Wu S, Song J, Chen T, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q (2020) Clinical and immunologic features in severe and moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Clin Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen IY, Chang SC, Wu HY, Yu TC, Wei WC, Lin S, Chien CL, Chang MF (2010) Upregulation of the Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand 2 via a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike-ACE2 Signaling Pathway. Journal of Virology 84:7703–7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu IM, Von Hehn CA, Woolf CJ (2012) Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nature neuroscience 15:1063–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotto KC, Wagner AH, Feng Y-Y, Kiwala S, Coffman AC, Spies G, Wollam A, Spies NC, Griffith OL, Griffith M (2018) DGIdb 3.0: a redesign and expansion of the drug-gene interaction database. Nucleic acids research 46:D1068–D1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling TK, Lamb TJ (2019) Emerging Roles for Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands in Immunity. Front Immunol 10:1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devesa I, Planells-Cases R, Fernandez-Ballester G, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Ferrer-Montiel A, Fernandez-Carvajal A (2011) Role of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in inflammation and sepsis. J Inflamm Res 4:67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR (2013) STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin AE, Patapoutian A (2010) Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J Clin Invest 120:3760–3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira A-M, Johnson R, Jungreis I, Loveland J, Mudge JM, Sisu C, Wright J, Armstrong J (2019) GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic acids research 47:D766–D773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furic L, Rong L, Larsson O, Koumakpayi IH, Yoshida K, Brueschke A, Petroulakis E, Robichaud N, Pollak M, Gaboury LA, Pandolfi PP, Saad F, Sonenberg N (2010) eIF4E phosphorylation promotes tumorigenesis and is associated with prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14134–14139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garceau D, Chauret N (2019) BLU-5937: A selective P2X3 antagonist with potent anti-tussive effect and no taste alteration. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 56:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DE et al. (2020) A SARS-CoV-2-Human Protein-Protein Interaction Map Reveals Drug Targets and Potential Drug-Repurposing. bioRxiv:2020.2003.2022.002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guptill V, Cui X, Khaibullina A, Keller JM, Spornick N, Mannes A, Iadarola M, Quezado ZM (2011) Disruption of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 can affect survival, bacterial clearance, and cytokine gene expression during murine sepsis. Anesthesiology 114:1190–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley SH, Bahia PK, Taylor-Clark TE (2014) Sensory nerve terminal mitochondrial dysfunction induces hyperexcitability in airway nociceptors via protein kinase C. Mol Pharmacol 85:839–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Zhang H, Mu S, Wei W, Jin C, Xue Y, Tong C, Zha Y, Song Z, Gu G (2020) Lactate dehydrogenase, a Risk Factor of Severe COVID-19 Patients. medRxiv:2020.2003.2024.20040162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hanamura K, Washburn HR, Sheffler-Collins SI, Xia NL, Henderson N, Tillu DV, Hassler S, Spellman DS, Zhang G, Neubert TA, Price TJ, Dalva MB (2017) Extracellular phosphorylation of a receptor tyrosine kinase controls synaptic localization of NMDA receptors and regulates pathological pain. PLoS Biol 15:e2002457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held KS, Chen BP, Kuziel WA, Rollins BJ, Lane TE (2004) Differential roles of CCL2 and CCR2 in host defense to coronavirus infection. Virology 329:251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson NT, Dalva MB (2018) EphBs and ephrin-Bs: Trans-synaptic organizers of synapse development and function. Mol Cell Neurosci 91:108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensellek S, Brell P, Schaible HG, Brauer R, Segond von Banchet G (2007) The cytokine TNFalpha increases the proportion of DRG neurones expressing the TRPV1 receptor via the TNFR1 receptor and ERK activation. Mol Cell Neurosci 36:381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdy B et al. (2012) Translational control of the activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB and production of type I interferon by phosphorylation of the translation factor eIF4 E. Nature immunology 13:543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C et al. (2020a) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Shi Y, Gong B, Jiang L, Liu X, Yang J, Tang J, You C, Jiang Q, Long B, Zeng T, Luo M, Zeng F, Zeng F, Wang S, Yang X, Yang Z (2020b) Blood single cell immune profiling reveals the interferon-MAPK pathway mediated adaptive immune response for COVID-19. medRxiv:2020.2003.2015.20033472.

- Kaelberer MM, Caceres AI, Jordt SE (2020) Activation of a nerve injury transcriptional signature in airway-innervating sensory neurons after Lipopolysaccharide induced lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A (2016) Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic acids research 44:W90–W97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W, Fischer A, Kurkowski R, Heym C (1992) The sensory and sympathetic innervation of guinea-pig lung and trachea as studied by retrograde neuronal tracing and double-labelling immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience 49:715–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupari J, Haring M, Agirre E, Castelo-Branco G, Ernfors P (2019) An atlas of vagal sensory neurons and their molecular specialization. Cell reports 27:2508–2523. e2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J (2020) Race to find COVID-19 treatments accelerates. Science 367:1412–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann A, Torre D, Keenan AB, Jagodnik KM, Lee HJ, Wang L, Silverstein MC, Ma’ayan A (2018) Massive mining of publicly available RNA-seq data from human and mouse. Nature communications 9:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson JN, El-Husseini A (2005) Building excitatory and inhibitory synapses: balancing neuroligin partnerships. Neuron 48:171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TC, Henderson TA, Carpenter AR, Ramirez IA, McHenry CL, Goldsmith AM, Ren X, Mentz GB, Mukherjee B, Robins TG, Joiner TA, Mohammad LS, Nguyen ER, Burns MA, Burke DT, Hershenson MB (2012) Nasal cytokine responses to natural colds in asthmatic children. Clin Exp Allergy 42:1734–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Hore Z, Harley P, Stanley FU, Michrowska A, Dahiya M, LaRussa F, Jager SE, Villa S, Denk F (2019) A transcriptional toolbox for exploring peripheral neuro-immune interactions. bioRxiv:813980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, Chen L, Li J, Wang X, Wang F, Liu L, Zhang S, Zhang Z (2020) The landscape of lung bronchoalveolar immune cells in COVID-19 revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. medRxiv:2020.2002.2023.20026690.

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ et al. (2017) Epiregulin and EGFR interactions are involved in pain processing. J Clin Invest 127:3353–3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megat S, Ray PR, Moy JK, Lou TF, Barragan-Iglesias P, Li Y, Pradhan G, Wanghzou A, Ahmad A, Burton MD, North RY, Dougherty PM, Khoutorsky A, Sonenberg N, Webster KR, Dussor G, Campbell ZT, Price TJ (2019) Nociceptor Translational Profiling Reveals the Ragulator-Rag GTPase Complex as a Critical Generator of Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci 39:393–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalovich D, Rodriguez-Perez N, Smolinska S, Pirozynski M, Mayhew D, Uddin S, Van Horn S, Sokolowska M, Altunbulakli C, Eljaszewicz A (2019) Obesity and disease severity magnify disturbed microbiome-immune interactions in asthma patients. Nature communications 10:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani T, Fukushi S, Saijo M, Kurane I, Morikawa S (2004) Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and its downstream targets in SARS coronavirus-infected cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319:1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy JK, Khoutorsky A, Asiedu MN, Black BJ, Kuhn JL, Barragan-Iglesias P, Megat S, Burton MD, Burgos-Vega CC, Melemedjian OK, Boitano S, Vagner J, Gkogkas CG, Pancrazio JJ, Mogil JS, Dussor G, Sonenberg N, Price TJ (2017) The MNK-eIF4E Signaling Axis Contributes to Injury-Induced Nociceptive Plasticity and the Development of Chronic Pain. J Neurosci 37:7481–7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narula M, McGovern AE, Yang SK, Farrell MJ, Mazzone SB (2014) Afferent neural pathways mediating cough in animals and humans. J Thorac Dis 6:S712–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RY, Li Y, Ray P, Rhines LD, Tatsui CE, Rao G, Johansson CA, Zhang H, Kim YH, Zhang B, Dussor G, Kim TH, Price TJ, Dougherty PM (2019) Electrophysiological and transcriptomic correlates of neuropathic pain in human dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain 142:1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramilowski JA, Goldberg T, Harshbarger J, Kloppmann E, Lizio M, Satagopam VP, Itoh M, Kawaji H, Carninci P, Rost B, Forrest AR (2015) A draft network of ligand-receptor-mediated multicellular signalling in human. Nat Commun 6:7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P, Torck A, Quigley L, Wangzhou A, Neiman M, Rao C, Lam T, Kim JY, Kim TH, Zhang MQ, Dussor G, Price TJ (2018) Comparative transcriptome profiling of the human and mouse dorsal root ganglia: an RNA-seq-based resource for pain and sensory neuroscience research. Pain 159:1325–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayamajhi M, Zhang Y, Miao EA (2013) Detection of pyroptosis by measuring released lactate dehydrogenase activity. Methods Mol Biol 1040:85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich SH et al. (2018) Structure-based Design of Pyridone-Aminal eFT508 Targeting Dysregulated Translation by Selective Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Interacting Kinases 1 and 2 (MNK1/2) Inhibition. J Med Chem 61:3516–3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl CR, Pasko BL, Khan HS, Kindt LM, Stamm CE, Franco LH, Hsia CC, Zhou M, Davis CR, Qin T, Gautron L, Burton MD, Mejia GL, Naik DK, Dussor G, Price TJ, Shiloh MU (2020) Mycobacterium tuberculosis Sulfolipid-1 Activates Nociceptive Neurons and Induces Cough. Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sann H, Pierau FK (1998) Efferent functions of C-fiber nociceptors. Z Rheumatol 57 Suppl 2:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiers S, Mwirigi J, Pradhan G, Kume M, Black B, Barragan-Iglesias P, Moy JK, Dussor G, Pancrazio JJ, Kroener S, Price TJ (2020) Reversal of peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain and cognitive dysfunction via genetic and tomivosertib targeting of MNK. Neuropsychopharmacology 45:524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springall DR, Cadieux A, Oliveira H, Su H, Royston D, Polak JM (1987) Retrograde tracing shows that CGRP-immunoreactive nerves of rat trachea and lung originate from vagal and dorsal root ganglia. J Auton Nerv Syst 20:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Mering CV (2019) STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot S et al. (2015) Silencing Nociceptor Neurons Reduces Allergic Airway Inflammation. Neuron 87:341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Li C, Huang A, Xia S, Lu S, Shi Z, Lu L, Jiang S, Yang Z, Wu Y, Ying T (2020) Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:382–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo JA, Fleming EL, Perlman S (2013) Transgenic CCL2 Expression in the Central Nervous System Results in a Dysregulated Immune Response and Enhanced Lethality after Coronavirus Infection. Journal of Virology 87:2376–2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, Abdo H, Lonnerberg P, Lou D, Hjerling-Leffler J, Haeggstrom J, Kharchenko O, Kharchenko PV (2015) Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature neuroscience 18:145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallrapp A, Burkett PR, Riesenfeld SJ, Kim SJ, Christian E, Abdulnour RE, Thakore PI, Schnell A, Lambden C, Herbst RH, Khan P, Tsujikawa K, Xavier RJ, Chiu IM, Levy BD, Regev A, Kuchroo VK (2019) Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Negatively Regulates Alarmin-Driven Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Responses. Immunity 51:709–723 e706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F (2020) Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. Journal of virology 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangzhou A, Paige C, Neerukonda SV, Dussor G, Ray PR, Price TJ (2020) A pharmacological interactome platform for discovery of pain mechanisms and targets. bioRxiv:2020.2004.2014.041715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Woolf CJ, Ma Q (2007) Nociceptors--noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron 55:353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Liu Y, Cao L, Wang D, Guo M, Guo D, Hu W, Yang J, Tang Z, Zhang Q, Shi M, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Lan K, Chen Y (2020a) Transcriptomic Characteristics of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid and Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in COVID-19 Patients. SSRN Electronic Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Liu Y, Cao L, Wang D, Guo M, Jiang A, Guo D, Hu W, Yang J, Tang Z, Wu H, Lin Y, Zhang M, Zhang Q, Shi M, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Lan K, Chen Y (2020b) Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q (2020) Structural basis for the recognition of SARSCoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367:1444–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates B, Braschi B, Gray KA, Seal RL, Tweedie S, Bruford EA (2017) Genenames.org: the HGNC and VGNC resources in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D619–D625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B (2020a) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Fu B, Zheng X, Wang D, Zhao C, qi Y, Sun R, Tian Z, Xu X, Wei H (2020b) Aberrant pathogenic GM-CSF+ T cells and inflammatory CD14+CD16+ monocytes in severe pulmonary syndrome patients of a new coronavirus. bioRxiv:2020.2002.2012.945576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]