Since it was first reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) in early January 2020, nearly 43,000 cases of a novel coronavirus (2019–nCoV) have been diagnosed in China with exportation events to over 20 countries [1]. Given the novelty of the causative pathogen, scientists have rushed to fill epidemiological, virological, and clinical knowledge gaps – resulting in over 50 new studies about the virus between January 10 and January 30 alone [2]. However, in an era where the immediacy of information has become an expectation of decision-makers and the general public alike, many of these studies have been shared first in the form of preprint papers – prior to peer review.

For the past three decades, preprint servers have become commonplace in the scientific publication ecosystem, and 2019–nCoV has prompted a seemingly unprecedented utilization of these platforms [3]. Though peer-review is critical for the validation of science, the ongoing outbreak has showcased the rapidity with which preprints can disseminate information during emergencies.

Here, we use both preprint and peer-reviewed studies that estimated the transmissibility potential (i.e. basic reproduction number, R0) of 2019–nCoV on or prior to February 1, 2020 to investigate the role preprints have had in information dissemination during the ongoing outbreak. We also analyze the agreement of preprint estimates as compared against those presented by peer-reviewed studies and propose a consensus-based approach for evaluating the validity of preprint findings during public health crises.

What We Did

To conduct our analysis, we collected publicly available data from scientific studies, news reports, and search trends pertaining to 2019–nCoV and its basic reproduction (or reproductive) number (R0). Defined as the average number of secondary infections a new case may infect in a fully susceptible population, estimates of R0 can provide decision-makers with insights into the epidemic potential of a given outbreak.

Relevant news reports and search trends were discovered via MediaCloud and Google Search Trends respectively and served as a proxy indicator for information dissemination [4, 5]. Meanwhile, relevant scientific studies were discovered through a combination of searches executed via Google Scholar and – to address possible delays in indexing – four popular public servers (i.e. arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, and SSRN) that we believe are representative of the relevant preprint literature. Search terms and specifications for each data source are outlined in Table 1. All studies discovered via Google Scholar, arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, and SSRN were manually checked for relevance to the topic area of interest. Only studies that included estimates for the basic reproduction number associated with 2019–nCoV in the body of the text were retained.

Table 1. Search terms and specifications for data discovery by data source.

Exact search terms are shown with Boolean operators as specified by each data source. Relevant studies were collected through February 1, 2020, and due to indexing delays on the Google Scholar platform, the preprint servers arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, and SSRN were used (in addition to Google Scholar) for study collection. Data for MediaCloud and Google Search Trends were collected From January 1, 2020 through February 9, 2020 to allow for baseline and posterior observation of news media and search interest in the topic area. Though geographic ranges of news media and search trends were specifiable, worldwide catchment was selected to ensure that international searches and media were captured in discovery.

| Data Source | Search Terms | Date Range | Geographic Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | • coronavirus reproduction • coronavirus reproductive |

February 1, 2019 – February 1, 2020 | not specifiable |

| Preprint Servers | • coronavirus reproduction • coronavirus reproductive |

January 1, 2020 – February 1, 2020 | not specifiable |

| MediaCloud | coronavirus AND (reproductive OR reproduction) | January 1, 2020 – February 9, 2020 | worldwide (global) |

| Google Search Trends | coronavirus reproductive + coronavirus reproduction | January 1, 2020 – February 9, 2020 | all media (global) |

After this initial data discovery phase, date of first publication, publication platform, review status (i.e. preprint vs. peer-reviewed), and methodological details were manually curated from each of the 11 individual studies (Table 2) [6-16]. R0 estimates were also extracted from each study for further analysis. In the event of multiple R0 estimates – due either to preprint revisions following the first version or the use of multiple approaches in a single study – each estimate was recorded and treated as a separate entry to represent all available knowledge at any given point in time (Table 2).

Table 2. Metadata collected for all R0 estimates [6-16].

For preprints that were revised before publication of the first relevant peer-reviewed study on January 29, the version number is indicated between parentheses as (n). When multiple R0 estimates were presented in a single study due to the use of multiple approaches, the version number is followed by a single decimal place to indicate the approach used as (n.n). If a first author published more than one relevant independent study before February 1, the version number is followed immediately by an alphabetical marker (ordered by date of publication) as (nx).

| ID | Date of Publication |

Publication Platform |

Modeling Method |

Temporal Data Used |

R0 Range Presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majumder and Mandl (1) | 23-Jan-20 | SSRN (preprint) | incidence decay + exponential adjustment | confirmed case counts | point estimates |

| Read et al. (1) | 24-Jan-20 | medRxiv (preprint) | deterministic compartmental metapopulation | confirmed case counts; travel data | 95% CI |

| Riou and Althaus (1) | 24-Jan-20 | bioRxiv (preprint) | stochastic simulations | none | 90% high density interval |

| Tang et al. | 24-Jan-20 | SSRN (preprint) | deterministic compartmental | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Zhao et al. (1a.1) | 24-Jan-20 | bioRxiv (preprint) | exponential growth model | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Zhao et al. (1a.2) | 24-Jan-20 | bioRxiv (preprint) | exponential growth | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Majumder and Mandl (2) | 26-Jan-20 | SSRN (preprint) | incidence decay + exponential adjustment | confirmed case counts | point estimates |

| Read et al. (2) | 27-Jan-20 | medRxiv (preprint) | deterministic compartmental metapopulation | confirmed case counts; travel data | 95% CI |

| Zhou et al. (1.1) | 28-Jan-20 | arXiv (preprint) | deterministic compartmental | confirmed case counts | point estimates |

| Zhou et al. (1.2) | 28-Jan-20 | arXiv (preprint) | deterministic compartmental | estimated case count based off of exportation events | point estimates |

| Li et al. | 29-Jan-20 | NEJM (peer- revieiwed) | renewal equations | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Riou and Althaus (2) | 30-Jan-20 | Eurosurveillance (peer-revieiwed) | stochastic simulations | none | 90% high density interval |

| Zhao et al. (2a.1) | 30-Jan-20 | IJID (peer-revieiwed) | exponential growth | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Zhao et al. (2a.2) | 30-Jan-20 | IJID (peer-revieiwed) | exponential growth | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

| Wu, Leung, and Leung | 31-Jan-20 | Lancet (peer- revieiwed) | Markov chain Monte Carlo | confirmed case counts | 95% CrI |

| Zhao et al. (1b) | 31-Jan-20 | JCM (peer- revieiwed) | simulation | confirmed case counts | 95% CI |

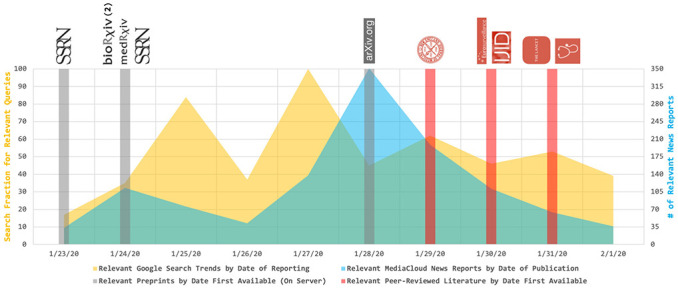

Given that the first known preprint estimates for R0 were posted to SSRN by us on January 23, search trend fractions and news report volume were plotted between January 23 and February 1 (Figure 1). Baseline data for both sources prior to January 23, 2020 yielded negligible interest and volume respectively, and data collected through February 9, 2020 demonstrated depreciating interest and volume following the catchment window in Figure 1 [4, 5]. To illustrate when each of the 11 relevant studies became available to the public, indicator bars were overlaid against the search trend and news report data by date of publication (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Search and news media interest in the basic reproduction number (R0) associated with 2019–nCoV as a function of time.

Indicator bars demonstrate when 11 different studies – all of which estimated the R0 associated with 2019–nCoV – were made available. Data are plotted from January 23, 2020 (i.e. the date of publication for the first study) through February 1, 2020. Though not shown here, search and news media interest prior to January 23, 2020 were negligible in the topic area, and interest continued to depreciate from February 2, 2020 through February 9, 2020 [4, 5].

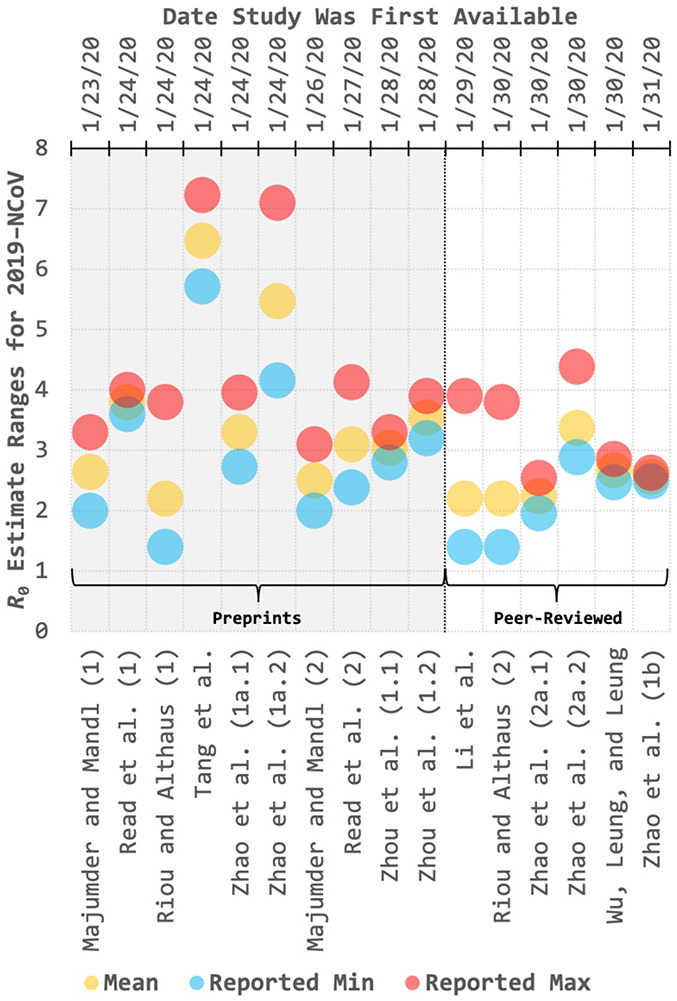

We then plotted each of the 16 R0 estimates produced by the 11 studies in Table 2, including both the mean and the estimate range (e.g. 95% CI, 95%CrI, etc.) presented. Estimates were plotted by date of publication and alphabetically there-in, offering a side-by-side comparison of preprint versus peer-reviewed results; averages and 95% confidence intervals were also computed for both groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Basic reproduction number (R0) mean and range estimates from 11 different studies of 2019–nCoV as a function of time.

Ranges presented vary by study (e.g. 95%CI, 95%CrI, etc.) and are presented in Table 2.

What We Found

Google Search Trends and MediaCloud data suggest that both general (i.e. search) interest and news media interest in the basic reproduction number (R0) associated with 2019–nCoV peaked prior to the publication of relevant peer-reviewed studies. In the selected time frame, search interest peaked on January 27 after a sharp increase between January 23 and January 25 immediately following the publication of 5 early preprint studies – all of which estimated R0 – to bioRxiv, medRxiv, and SSRN. Meanwhile, news media interest peaked on January 28, coinciding with a 6th preprint study published on arXiv (Figure 1). The first peer-reviewed estimates were then published by Li et al. on January 29 at 5:00 PM EST – as is standard for The New England Journal of Medicine – followed by four additional peer-reviewed studies in Eurosurveillance, The International Journal of Infectious Diseases, The Lancet, and Journal of Clinical Medicine through February 1 [12, 17].

Average R0 estimates across both the preprint group and the peer-reviewed group were 3.61 [95%CI: 2.77, 4.45] and 2.54 [95%CI: 2.17, 2.91] respectively – demonstrating overlap in 95% confidence intervals despite a wide diversity of modeling methods and data sources used both in-group and across-group (Table 2). Though the average mean for the preprint group was higher than that of the peer-reviewed group, this effect was driven primarily by two outlier estimates (R0 > 95%CI maximum) as is depicted in Figure 2 [9, 10]. Exclusion of these two estimates using a consensus-based approach based on the 95% confidence interval yielded an average R0 estimate of 3.02 [95% CI: 2.65, 3.39] for the preprint group.

Notably, two of the studies in the peer-reviewed group had previously been published as preprints [13, 14]. Though estimates presented by Riou and Althaus remained unchanged following peer review, estimates presented by Zhao et al. were higher prior to peer review than they were following it.

What It Means

Due to the rapidity of their release, our findings suggest that preprints – rather than peer-reviewed literature in the same topic area – may be driving discourse related to the ongoing 2019–nCoV outbreak. Though our analysis focuses on search trend and news media data as a measure for general discourse, it is likely that preprints are also influencing policymaking discussions given that the WHO announced on January 26, 2020 that they would be creating a repository of relevant studies – including those that have not yet been peer-reviewed [18].

Nevertheless, despite the advantages of speedy information delivery, lack of peer review can also potentially translate into issues of credibility and misinformation – intentional and unintentional alike. This particular drawback has been highlighted during the ongoing outbreak especially following the high-profile withdrawal of a virology study from the preprint server bioRxiv, which erroneously claimed that 2019–nCoV contained HIV “insertions” [19]. Thankfully, the very fact that this study was withdrawn showcases the power of “public” peer-review during emergencies; the withdrawal itself appears to have been prompted by public outcry from dozens of scientists from around the globe who had access to the study because it was placed on a public server [20]. Nevertheless, instances like this one showcase the need for caution when considering the science put forth by any one preprint.

With this in mind, taking multiple studies into consideration as presented in our analysis can help operationalize the kind of caution necessitated by preprints while simultaneously allowing for important, robust insights prior to the publication of a peer-reviewed study in the same topic area. This kind of collective, consensus-based approach is arguably easiest when the research of interest is quantitative in nature; nevertheless, given that many critical epidemiological parameters that inform decision-making (e.g. incubation period, generation time, etc.) are quantitative, our proposed approach could work well in these contexts as well.

Bearing cautious consideration, our work demonstrates the powerful role preprints can play during public health crises due to the timeliness with which they can disseminate new information. While primacy and peer-reviewed publications are key metrics in scientific advancement, the impact of preprints on discourse and decision-making pertaining to the ongoing 2019–nCoV outbreak suggests that we must rethink how we reward and recognize community contributions during current and future public health crises.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement – This work was supported in part by grant T32HD040128 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest – The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References.

- [1].Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV): Situation Report – 22. The World Health Organization, February 2020. (https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200211-sitrep-22-ncov.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- [2].China coronavirus: how many papers have been published? Nature, January 2020. (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00253-8). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [3].Preprints can fill a void in times of rapidly changing science. STAT, January 2020. (https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/31/preprints-fill-void-rapidly-changing-science/). [Google Scholar]

- [4].MediaCloud. February 2020. (https://mediacloud.org/).

- [5].Google Search Trends. February 2020. (https://trends.google.com/).

- [6].Majumder MS, Mandl KD. Early Transmissibility Assessment of a Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. SSRN; 2020; doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3524675 (https://tinyurl.com/rkzrmtv [v1], https://tinyurl.com/tbu796z [v2]). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Read JM, Bridgen JRE, Cummings DAT, et al. Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: early estimation of epidemiological parameters and epidemic predictions. medRxiv 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.01.23.20018549 (https://tinyurl.com/vt9nmsw [v1], https://tinyurl.com/soroa5o [v2]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [8].Riou J, Althaus CL. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019-nCoV. bioRxiv 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.01.23.917351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tang B, Wang X, Li Q, et al. Estimation of the Transmission Risk of 2019-nCov and Its Implication for Public Health Interventions. SSRN; 2020; doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3525558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhao S, Ran J, Musa SS, et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. bioRxiv 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.01.23.916395 (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.23.916395v1 [v1]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [11].Zhou T, Liu Q, Yang Z, et al. Preliminary prediction of the basic reproduction number of the Wuhan novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV. arXiv 2020. (https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.10530v1 [v1]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [12].Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. NEJM 2020; doi: 10.1056/NETMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Riou J, Althaus CL. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Euro Surveill 2020; 25(4): 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhao S, Lin Q, Ran J, et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wu KT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 2020; doi: https://doi.org.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhao S, Musa SS, Lin Q, et al. Estimating the Unreported Number of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Cases in China in the First Half of January 2020: A Data-Driven Modelling Analysis of the Early Outbreak. J Clin Med 2020; 9(2): 10.3390/jcm9020388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Frequently Asked Questions. The New England Journal of Medicine, February 2020. (https://www.nejm.org/media-center/frequently-asked-questions).

- [18].New Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The World Health Organization, January 2020. (https://twitter.com/WHO/status/1221475167869833217) [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pradhan P, Pandey AK, Mishra A, et al. Uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag (WITHDRAWN). bioRxiv 2020; doi: 10.1101/2020.01.30.927871 [DOI]

- [20].Quick retraction of a faulty coronavirus paper was a good moment for science. STAT, February 2020. (https://www.statnews.com/2020/02/03/retraction-faulty-coronavirus-paper-good-moment-for-science/). [Google Scholar]