Highlights

-

•

CA/CPB nanofibers have a filtration efficiency of 99.9 % for aerosol (7−300 nm).

-

•

The Ergun’s porosity of the nanofibers is 98 % and the permeability about 10−11 m2.

-

•

CA/CPB nanofibers are biodegradable and sustainable novel air filters.

-

•

The nanofibers are able to retention environmental PM2.5, BC and also virus.

Keywords: Nanofiber, Indoor air filtration, Nano-and microparticles retention, Air pollution

Abstract

The increase of the industrialization process brought the growth of pollutant emissions into the atmosphere. At the same time, the demand for advances in aerosol filtration is evolving towards more sustainable technologies. Electrospinning is gaining notoriety, once it enables to produce polymeric nanofibers with different additives and also the obtaining of small pore sizes and fiber diameters; desirable features for air filtration materials. Therefore, this work aims to evaluate the filtration performance of cellulose acetate (CA) nanofibers and cationic surfactant cetylpyridinium bromide (CPB) produced by electrospinning technique for retention of aerosol nanoparticles. The pressure drop and collection efficiency measurements of sodium chloride (NaCl) aerosol particles (diameters from 7 to 300 nm) were performed using Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS). The average diameter of the electrospun nanofibers used was 239 nm, ranging from 113 to 398 nm. Experimental results indicated that the nanofibers showed good permeability (10−11 m2) and high-efficiency filtration for aerosol nanoparticles (about 100 %), which can include black carbon (BC) and the new coronavirus. The pressure drop was 1.8 kPa at 1.6 cm s-1, which is similar to reported for some high-efficiency nanofiber filters. In addition, it also retains BC particles present in air, which was about 90 % for 375 nm and about 60 % for the 880 nm wavelength. Finally, this research provided information for future designs of indoor air filters and filter media for facial masks with renewable, non-toxic biodegradable, and potential antibacterial characteristics.

1. Introduction

The demands due to population and urban areas growth have exerted pressure for rising industrial production and energy consumption. Consequently, substantial amounts of atmospheric pollutants have been generated, causing damages to materials, fauna, flora, and especially to human health (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2012).

Among these pollutants, atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is recognized as the main air pollutant problem, which is emitted mainly by combustion processes, road dust suspension, electricity generation and industrial processes, besides secondary formation (Smith, 1993; Szybist et al., 2007). Several studies show its effect on climate (Lashof and Ahuja, 1990; Stohl et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2010) and human health, being mainly associated with respiratory (Bakonyi et al., 2004; Lin, 2005; Luginaah et al., 2005; Reid et al., 2019) and circulatory diseases (Ardiles et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019a; Maté et al., 2010), as well as mental disorders (Almendra et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2017; Song et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2020).

During breathing, the human respiratory system is capable to prevent the entrance of most particulate matter. However, for the small ones, especially PM2.5, around 96 % can penetrate the respiratory tract (Löndahl et al., 2007; Xing et al., 2016). Furthermore, studies have reported that small particles have larger surface areas, being capable of carrying various toxic compounds (Dieme et al., 2012; Kendall et al., 2004; Senlin et al., 2008; Xing et al., 2016). Therefore, controlling the concentration of these particles is important, mainly in indoor environments (Kelly and Fussell, 2019; Li et al., 2017), since it causes millions of premature deaths worldwide (Chowdhury and Dey, 2016; Fang et al., 2016; Giannadaki et al., 2016).

Black Carbon (BC) is an atmospheric pollutant and a type of carbonaceous atmospheric particulate material formed in the combustion process of carbon-containing materials, mainly by burning fossil fuels (coal, diesel, gasoline) and biomass, whose fresh BC particulate ranged from 50 to 80 nm of diameter (Bond et al., 2013; Colbeck, 2008; Wallace and Hobbs, 2005). It is also a short-lived climate pollutant that affects the thermal balance of the planet's surface (Bond et al., 2013) and also human health, impacting the circulatory and respiratory systems (Galdos et al., 2013; Janssen et al., 2011; Segalin et al., 2016) and, as recently verified, the nervous system (Maher et al., 2016; Pun et al., 2019).

The recent pandemic due to COVID-19, causing more than 550 thouhsand deaths in the world, is due to the transmission of droplets expelled during the sneeze, cough or even conversation of a person contamined by the virus (virus size ranging from 50 to 200 nm, according to Chen et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Thus, efficient filters for retaining not only the droplets but also the virus are in fact necessary because the virus can remain suspended in the air for 3 h or more (Doremalen et al., 2020). The High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters are widely used in indoor air pollution control by air conditioning system and are generally composed of glass fibers (Thomas et al., 1999). Its main features are the large pressure drop, which occurs during the operation, making the energy consumption increase. (Thomas et al., 1999; Zaatari et al., 2014). The most common air filters are composed of porous materials in a solid substrate, with very small pore sizes but also low porosity (<30 %) (Hinds, 1999; Liu et al., 2017). Recent studies denote the application of nanofibrous mats (Lv et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2017), as they usually have high porosity (>70 %), large surface-to-volume ratio, are thin and have higher air filtration efficiency (Liu et al., 2015a,b).

Electrospinning is a very efficient and low cost technique to produce nanofibers for several applications. It allows the use of different polymeric solutions and additives to improve and/or assign any characteristic to the mats (Huang et al., 2003). For example, the fiber diameter of the material obtained by this technique could be controlled (ranging from 10 to 1000 nanometers), once the process parameters (flow rate, voltage, polymer concentration, collector distance) can be regulated (Zhao et al., 2016). Currently, the use of nanofibers obtained by this technique has been intensively studied in indoor air filtration (Bian et al., 2020; Robert and Nallathambi, 2020), and the authors suggest that reducing the fiber diameter contributes to improve filtration performance (Xia et al., 2018). Future perspectives imply the use of nonprejudicial solvents, as well as bio-based polymers to develop clean and safe technologies (Bortolassi et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019b; Matulevicius et al., 2016; Min et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019).

Cellulose acetate (CA) is a semi-synthetic and biodegradable polymer (Buchanan et al., 1993; Puls et al., 2011) widely used to produce nanofibers by electrospinning (Anitha et al., 2013; Nicosia et al., 2016; Sultana and Zainal, 2016; Wutticharoenmongkol et al., 2019). Due to the common presence of beads in their fibers, thermal and mechanical resistance properties are compromised (Kendouli et al., 2014). Thus, the use of cationic surfactants as an additive proves to be an effective strategy for reducing beads, improving those properties and also reducing fiber diameters (Abutaleb et al., 2017; de Almeida et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2010). Besides, it can attribute biocide characteristics to the nanofibers, such us, the cationic surfactant cetylpyridinium bromide (CPB) that is an antibacterial agent widely used in the pharmaceutical industry (Cole et al., 2011; Lukáč et al., 2013; Malek and Ramli, 2015; Wu et al., 2020).

Thus, this work aims to produce biodegradable and non-toxic nanofibers of natural-based CA polymer modified with CPB surfactant by electrospinning technique, and evaluate their performance in filtering airborne nanoparticles. Additionally, nanofiber retention efficiencies for atmospheric PM2.5 and BC were analyzed.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The nanofibers were produced using cellulose acetate (CA) as polymer (average molecular weight 30 kDa) and cationic surfactant cetylpyridinium bromide (CPB), both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. The solvents for preparing the polymeric solution were a mixture of acetic acid (Synth, São Paulo, Brazil) and distilled water (3:1 v/v). Pure aqueous solution of 1 g L−1 NaCl (CHEMIS) was used to generate nanoparticles (density 2.17 g cm−3) necessary for filter performance tests.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of CA/CPB nanofibers

The nanofibers were made using 21 % (w/v) of CA and 0.5 % (w/v) of the surfactant CPB (de Almeida et al., 2020) in a home-made electrospinning apparatus, composed of a high voltage power supply, a syringe pump (WPI - SP100I, Sarasota-FL, USA), and static aluminum collector in circular format. The optimal concentrations were achieved based in findings from a previous work made in our research group (de Almeida et al., 2020). The flow rate was maintained at 0.7 mL h−1, the voltage at 18 kV and the distance between the needle and the collector was 10 cm. The electrospinning process was performed for 3 h to produce thin films to be used as filter media. Subsequently, the nanofibers were immediately conditioned in an exhaust system to evaporate the solvent traces remaining in the mats.

The morphology of the nanofibers produced was characterized by scanning electronic microscopy (SEM), using a Quanta 250 (Philip-FEI), equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS); the samples were dispersed on double-sided tape coated with a thin layer of gold (30 nm). The average diameter was measured using the Software Size Meter® 1.1.

2.2.2. Filtration performance of nanofiber filters

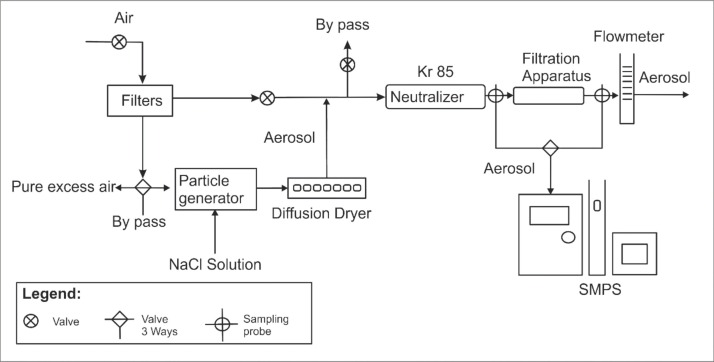

Fig. 1 shows a scheme of the experimental unit used in this research to analyze the filtration performance of nanofiber filters. It consists of an air compressor (Shultz Shultz, Joinville, Brazil), air purification filters (Model A917A-8104N-000 and 0A0−000), an atomizer aerosol generator (Model 3079, TSI, Shoreview-MN, USA), a diffusion dryer (Norgren, Birmingham, UK), a Krypton and Americium neutralizing source (Model 3054, TSI), filter apparatus, flowmeter size 3 (Gilmont Instruments, Inc., Barrington-IL, USA) and a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) device formed by electrostatic classifier (Model 3080, TSI), differential mobility analyzer and ultrafine particles counter (Model 3776, TSI).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of equipment used for permeability and nanoparticle filtration efficiency tests. Adapted from: de Barros et al. (2014).

The filtration tests were performed in circular specimens with 47 mm of diameter and about 500 nm of thickness at constant surface speed of 1.59 cm s−1, a flow rate of 500 mL min−1, and 5.3 cm2 of filtration area. Since the sodium chloride (NaCl) nanoparticles were generated from an aqueous solution (concentration of 1 g L−1), they passed downstream and upstream and the particle number size distribution was measured, in order to obtain the nanofiber efficiency using particle analyzer by electric mobility. This process was repeated two times to obtain an average efficiency and the standard deviation.

The filtration efficiency was calculated based on particles concentration before and after passing through the filter media.

2.2.3. Permeability and pressure drop tests

The permeability experiments were carried out in duplicate, varying the flow rate from 100 to 900 mL min−1. The pressure drop was measured at each flow rate interval with a digital manometer (VelociCalc Model 3A-181WP09, TSI), which was coupled to the test system, as shown in the scheme of Fig. 1. The permeability constant (k1) of the filter was determined theoretically, in order to evaluate the resistance of the filter media to air flow using Eq. (1) (Innocentini et al., 2006):

| (1) |

where L represents the thickness of the filter, μ is the viscosity of the fluid (air), k1 and k2 are permeability constants of the filter, ρg represents the density of the gas (air) and vs is the surface velocity. ΔP is the pressure drop: the difference between the input and output pressures during the passage of the air containing particles through the filter.

The experiments were conducted at low filtration velocity; therefore, the second term of Eq. (1) can be neglected; and the Eq. (2) (Darcy's Law) can be applied:

| (2) |

The empirical porosity (ε) of the filter media was calculated as proposed by Ergum (1952), using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where dp is the average diameter of the NaCl particles.

2.2.4. Performance of nanofiber filter media for retention atmospheric PM2.5 and BC

In order to enhance the application of nanofibers as an air filter for particle retention, environmental tests were performed using the mats as a filter media to collect the PM2.5 and BC particles present in the atmosphere. For PM2.5, two personal collector units MIE pDR-1500™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used (Moreira et al., 2018; Shakya et al., 2017; Sousan et al., 2016). They were installed at the Federal University of Technology – Paraná (campus at Londrina-PR, Brazil) in a laboratory room at ground level, with the entrances positioned outside the window to keep the equipment protected from weather conditions. In one equipment a quartz filter (QM-A with 37 mm and 2.2 μm pore size Whatman™, China) was placed inside and in another the CA/CPB nanofiber filter (de Almeida et al., 2020). Both equipments operated simultaneously and collected airborne particulate matter up to 2.5 μm diameter at 2.0 L min−1. The sampling period in each test was 2 days (48 h), and four tests (n = 4) were performed. For determining the PM2.5 mass retained in the filters, they were weighed before and after sampling, using a microanalytical balance, model MX5 (Mettler Toledo, USA) with a precision of 1 μg and discharged electrostatically, through a Haugstatic charge neutralizer (Mettler Toledo, USA).

Furthermore, to assess whether the nanofiber filter retains carbonaceous particles (i.e., BC), the microAeth® equipment model MA200 (AethLabs, San Francisco-CA, USA), coupled with a holder containing the CA/CPB nanofiber filter, was used, as shown in Fig. 2 . The inlet was placed outside the window of the sample location, and the measuring time in each test was of 24 h, with three replicates (n = 3). The operating flow rate used was 0.15 L min−1 with a measurement time resolution of 1 min and at 5 different wavelengths (880 nm, 625 nm, 528 nm, 470 nm, and 375 nm).

Fig. 2.

MA200 carbonaceous particle monitor with the holder containing the CA/CPB nanofiber.

Simultaneously, BC concentrations without the CA/CPB nanofiber were measured at same site using the Aethalometer model AE42 (Magee Scientific, EUA). The BC concentrations were determined and analyzed at 880 nm and 375 nm; 375 nm being the most sensitive wavelengths to the carbonaceous originating from wood smoke, biomass burning and tobacco; while 880 nm is the standard wavelength to measure BC particles (Wang, 2019).

Statistical tests were performed to determine if the data obtained by Aethalometer and microAeth were similar. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine data distribution and the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for p-value = 0.05 using Origin Pro 8 software.

The average BC retention efficiency was calculated on the basis of the difference between the BC concentrations measured with and without CA/CPB nanofibers.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. CA/CPB nanofibers

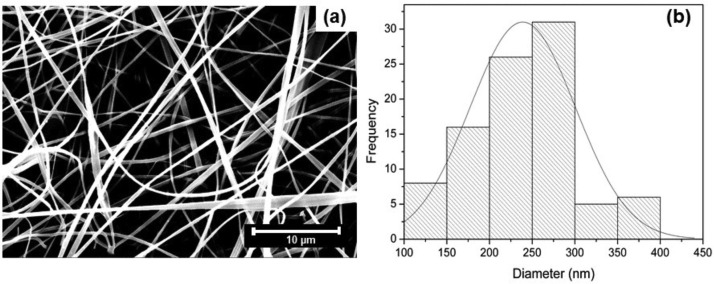

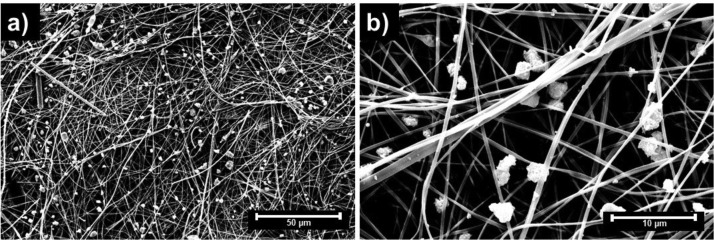

The nanofibers produced by electrospinning presented a normal diameter distribution (200 to 300 nm), as shown in Fig. 3 , and according to the results found in de Almeida et al. (2020). Fig. 3 shows the SEM image of mats and their frequency diameter distribution of nanofibers. A regular and uniform morphology was obtained.

Fig. 3.

(a) SEM image and (b) frequency diameter distribution of nanofibers produced with 21 % of CA and 0.5 % of CPB.

The mechanical properties of the CA/CPB nanofibers are 2.71 (± 0.45) MPa of tensile strength; 1.38 (± 0.50) % elongation at break; and 46.39 MPa Young’s modulus. The development and characterization of these nanofibers are presented in details in de Almeida et al. (2020).

Studies regarding air filtration materials indicate that small fiber diameters are useful to improve filtration performance (Hosseini and Tafreshi, 2010; Shou et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 1999), especially smaller aerosol particles, such as BC and virus. The non-alignment of fibers is also a desirable characteristic for air filters as obtained in the CA/CPB nanofibers (Fig. 3a).

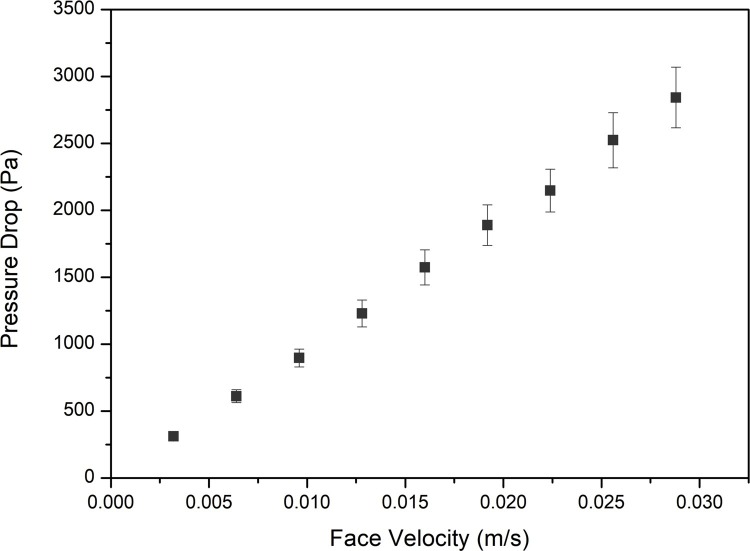

3.2. Permeability and pressure drop tests

Fig. 4 presents the results obtained from permeability tests performed in the filter media (about 700 μm of thickness) with clean nanofibers. As expected, the pressure drop increases with nanofiber thickness as a function of superficial velocity, since the impaction process occurs under the membrane. The nanofiber filter produced operated in very high-pressure drop, when compared to commercial air filters, due to the smaller pore sizes in relation to the average, which is about 10 nm (de Almeida et al., 2020). High-pressure drop is a common issue in some nanofiber membrane filters, as well as in HEPA filters.

Fig. 4.

Average pressure drop as a function of face velocity using CA/CPB nanofiber filter.

For polyamide 6 electrospun nanofibers, Jianyong and Jianchun (2015) found very high pressure drops, about 12 kPa for 0.001 m s−1. In the case of electrospun polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofibers with cellulose filter, Cho et al. (2013) obtained about 11 kPa pressure drop for 0.1 m s−1 of face velocity. The fiber diameter obtained in their nanofibers was similar to the CA/CPB nanofibers (about 300 nm).

In the research performed by Xia et al. (2018) the relation between the pressure drop and face velocity for electrospun nanofiber air filters was examined. They also investigated the behavior of different spinning times and, for nylon nanofibers, the shortest process (20 min) exhibited the lowest pressure drop (about 100 Pa). This shows that the thickness of the nanofiber is directly proportional to the increase in pressure drop.

Using Darcy Eq. (2) and Ergun Eq. (3) equations, it was possible to calculate the permeability (k1) and porosity (ε) values of CA/CPB nanofibers for the filtration rate of 0.0159 m s−1. The respective values for pressure drop, porosity and permeability are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Pressure drop (ΔP/L), porosity (ε) and permeability constant (k1) for CA/CPB nanofibers obtained by electrospinning.

| CA/CPB nanofibers | |

|---|---|

| ΔP/L 1 (kPa m−1) | 2166.62 |

| ΔP/L 2 (kPa m−1) | 2149.13 |

| ε (%) | 98.09 ± 0.01 |

| k1 (m2) x 10−11 | 3.48· ± 0.56 |

Barhate et al. (2006) produced PAN nanofibers by electrospinning and tested them for airborne particle filtration. In their work, the Darcy and Ergun equations were used for calculating the permeability and porosity of nanofibers, respectively. The value obtained for permeability was of the same order of magnitude as that obtained in this work for CA/CPB nanofibers (10−11 m2), and the porosity (96 %) was slightly lower than those found in this work (98 %).

Another research, conducted by Bortolassi et al. (2019), used the same module for air filtration tests for developing electrospun PAN nanofibers, but with the addition of silver nanoparticles, in order to give bactericidal characteristics to this particulate filter. They used these same equations, and found permeability and porosity values in the same order of magnitude as those found in the present work, ranging from 95 to 97 %, depending on the amount of silver nanoparticles added. The permeability constant are higher than those in glass fiber HEPA and ULPA (Ultra Low Penetration Air Filter) filters, which are on the order of 10−12 m2(Yun et al., 2007). The operation life of the CA/CPB nanofibers should be about 6 months to 1 year, like a HEPA filters composed of glass fiber and borosilicate microfibers which presents similar permeability (Bortolassi et al., 2017).

3.3. Filtration performance of nanofiber filters

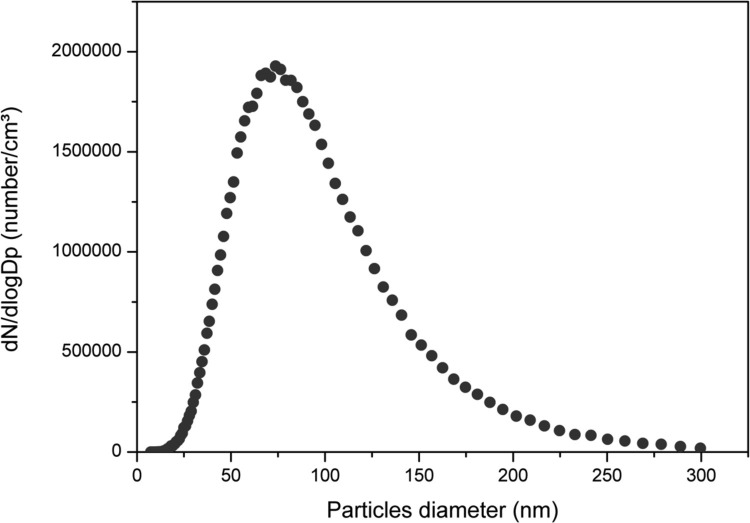

Fig. 5 shows the particle number size distribution of NaCl that was generated by the atomizer, in order to determine the filtration efficiency. A narrow distribution was obtained with an average diameter of approximately 80 nm and a median of 45 nm.

Fig. 5.

Particle number size distribution of NaCl generated by the atomizer.

An important advantage of such mats is the high-efficiency filtration for nano size particles, which is almost 100 %, considering the particle number size distribution generated of NaCl (7 to 300 nm). Besides, the CA modification performed by the addition of the surfactant improved the thermal and mechanical resistances (Abutaleb et al., 2017) without loosing their biodegradability and water resistance properties. Further, the CPB addition should assign biocide characteristics to the nanofibers. Malek and Ramli (2015), for example, modified the kaolinite with CPB, and they found an antibacterial activity for CPB concentrations ≥ 1.49 mmol/L, which is a lower value than it used in this work. Moreover, CA is a naturally sourced (renewable) polymer (Goetz et al., 2016). Other relevant aspect is that this nanofiber is also capable of retaining the 2019 coronavirus, once the virus is about 50 to 200 nm of size (Chen et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020) and has around 3 h of stability in aerosol (Doremalen et al., 2020). High-efficiency filtration was obtained even for smaller particles (99.99 %) with particle size diameter lower than 10 nm. Xia et al. (2018) presented particle retention efficiency data, with sizes between 200 and 500 nm for several electrospun nanofibers and most of them were above 95 %. The efficiency results obtained by Zhang et al. (2009) using electrospun Nylon 6 nanofibers ranged from 95 to 98 % for particles smaller than 50 nm, however, it is a non-degradable synthetic polymer. Liu et al. (2015b) found efficiency of 99.92 % for electrospun PAN nanofibers (ΔP =208 Pa), but they used NaCl larger nanoparticles, ranging from 300 to 500 nm. In the work of Yin et al. (2013) electrospun polyamide 6 membranes were produced, and an efficiency of about 80 % was obtained for particles with 300 nm in size and using the membranes with a substrate. As pointed out, other works have achieved high-efficiency filtration in mats produced through electrospinning technique. However, it was made using larger particle sizes and mainly non-natural and biodegradable mats. This is an important issue considering the use of nanofiber as filter media, e.g. in air conditioning systems and particularly in facial masks, since it can prevent environmental impacts associated with the disposal of these materials (Das et al., 2020).

3.4. Performance of nanofiber filter for retention atmospheric PM2.5 and BC

As mentioned, the performance of CA/CPB nanofiber for atmospheric PM2.5 and BC retention was evaluated by comparing the mass retained in the nanofiber with that of the commercial quartz filter, as well as measuring atmospheric BC simultaneously with and without the CA/CPB filter. From the environmental tests performed, it was possible to obtain the mass of PM2.5, collected in the CA/CPB filter and commercial quartz filters, as shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Mass of PM2.5 retained by the CA/CPB nanofibers and commercial quartz filters.

| Filter | Mass of PM2.5(μg) |

|

|---|---|---|

| CA/CPB Nanofibers | Quartz Fibers | |

| 1 | 171.0 ± 11.8 | 82.0 ± 1.2 |

| 2 | 161.7 ± 5.4 | 118.7 ± 2.3 |

| 3 | 167.0 ± 3.2 | 94.5 ± 3.4 |

| 4 | 139.3 ± 4.1 | 25.3 ± 4.5 |

The variability observed in the mass of the filters (Table 2) is due to the change of the meteorological conditions and emission sources between the sampling days of each filter. This influence was pronounced for filter 4, which presented the lowest mass in both filters associated with the occurrence of rainfall in the sampling period for this filter. In addition, humidity probably exerted a higher influence on the mass of the quartz filter compared to the CA/CPB filter. The CA/CPB nanofiber filters collected up to twice as much particulate mass as quartz filters, which had 6 kPa pressure drop in 0.4 m s−1 face velocity (Zíková et al., 2015). This behavior is possibly due to the reduced pore size of CA/CPB nanofiber (about 10 nm), when compared to the commercial filter, which presents 2.2 μm according to the manufacturer’s technical information. A PM2.5 impactor was used which probably collected larger particles than these pore sizes across the filter cake, and justifies the mass found in the quartz filters. Moreover, the SEM images of CA/CPB nanofibers after PM2.5 sampling have shown very small particles across the nanofibers, as shown in Fig. 6 .

Fig. 6.

SEM images of CA/CPB nanofiber filter after PM2.5 sampling zoomed at 2000 (a) and 10,000 (b) magnifications.

Although, the contribution of ultrafine particles (<0.1 μm) in relation to the total mass retained is negligible, this constitutes an important fraction of the particle number, which is also recognized for crossing the physical barriers of human body and for generating various health damages.

Concerning BC measurements, the concentration data measured by both equipments (Aethalometer and microAeth) were compared in order to know if there was no statistical difference. From the Shapiro-Wilk test results, it was possible to demonstrate that the distribution of BC concentrations at both wavelengths (375 and 880 nm) was not normal. Then, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test could be applied to BC concentrations, showing that for the p-value = 0.05 there is no significant difference between the concentrations measured by both equipments. Based on this result, it was assumed that the BC concentrations obtained through the Aethalometer equipment were those present in the atmosphere of the site, which were measured without using the CA/CPB medium nanofiber. The BC concentrations at 375 nm and 880 nm, as well as the global filtration efficiency calculated are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

BC concentrations at 375 nm and 880 nm and their filtration efficiency for both wavelengths.

| Filter | BC concentration (ng m−3) |

Global Filtration Efficiency (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 375 nm | 880 nm | 375 nm | 880 nm | ||

| 1 | 1051.79 | 950.53 | 90.34 | 74.53 | |

| 2 | 831.53 | 721.14 | 91.65 | 65.35 | |

| 3 | 577.35 | 453.07 | 76.93 | 53.85 | |

| Average | 820.23 | 708.25 | 86.31 | 64.58 | |

| Standard Error | 137.08 | 143.75 | 4.70 | 5.98 | |

The BC concentration and filtration efficiency were higher at 375 nm when compared to those obtained at 880 nm wavelength. A higher concentration indicates the influence of biomass burning sources at the sampling site, which has already been evidenced in other works (Beal et al., 2017; Martins et al., 2018). By comparing the filtration efficiency, there is a certain variability that could be related to the BC concentrations, since in both wavelengths the filtration efficiency, in general, decreased as the concentrations also decreased. Furthermore, as already known, filters membrane are not exactly equal among themselves, bringing a significant degree of heterogeneity, even with those commercially produced, which may partially justify the variability found in the filtration efficiency. Further tests under controlled conditions should be performed. However, it was possible to observe that the CA/CPB nanofiber filter was able to retain BC particles and, more efficiently, those carbonaceous particles generated by biomass burning.

The products obtained by electrospinning technique, specially for air filter market, is growing quickly and various companies already supply it. However, some issues still need to be improved when scaling up the production of these nanofibers, such as low productivity and quality control (Persano et al., 2013; Thenmozhi et al., 2017; Vass et al., 2019). On the raw material, CA is a commercial product as well as the acetic acid, and are abundant raw materials to produce the nanofibers. The estimated cost to produce the filter (1 m2) is around 2 (two) dollars (for laboratory-scale) and should be reduced by increasing to industrial-scale. Therefore, further studies are needed to best transfer these technologies into industrial applications.

The use of this material as an air filter media is described in a Brazilian patent, number BR 10 2020 014814 1, at the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), Brazil.

4. Conclusions

In this article, electrospun CA/CPB nanofibers were produced and their application as filtration media was investigated. Good filtration performance was obtained for NaCl nanoparticles with 7 to 300 nm of size, with almost 100 % efficiency and 1.8 kPa pressure drop.

The permeability and porosity were similar to those obtained by the same technique and were about 10−11 m2 and 98 %, respectively.

The environmental measurements tests showed that CA/CPB nanofiber was also able to retain atmospheric PM2.5, and with higher efficiency when compared to commercial quartz fiber-based filters. In addition, the CA/CPB nanofiber filter also retained BC particles with high efficiencies (about 90 % for 375 nm and about 60 % for the 880 nm wavelength), and higher for carbonaceous particles originating from biomass burning, which represents the smallest fraction of the PM2.5.

From the results obtained of this research, it is possible to conclude that CA/CPB could be applied for capturing particles smaller than 300 nm with high-efficiency filtration including the 2019 novel coronavirus. Finally, this research provided information for future designs of indoor air filter materials in air conditioning equipment, particularly in hospitals, once the pressure drop could be decreased as the CA/CPB nanofibers could be used as a thin layer associated with a thin substrate. Another possible use of it is as a filter media for facial masks that has a short-therm use, especially due to its potential antibacterial properties. Thus, the use of biodegradable material in its composition could reduce the environmental impacts by the disposal of a large amount of these waste.

Data avaliability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study (thesis).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq), process No. 306862/2018-2. This study was financed in part by the Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES), finance Code 001.

References

- Abutaleb A., Lolla D., Aljuhani A., Shin H.U. Effects of surfactants on the morphology and properties of electrospun polyetherimide fibers. Fibers. 2017;5:1–14. doi: 10.3390/fib5030033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almendra R., Loureiro A., Silva G., Vasconcelos J., Santana P. Short-term impacts of air temperature on hospitalizations for mental disorders in Lisbon. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;647:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anitha S., Brabu B., John Thiruvadigal D., Gopalakrishnan C., Natarajan T.S. Optical, bactericidal and water repellent properties of electrospun nano-composite membranes of cellulose acetate and ZnO. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;97:856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardiles L.G., Tadano Y.S., Costa S., Urbina V., Capucim M.N., da Silva I., Braga A., Martins J.A., Martins L.D. Negative Binomial regression model for analysis of the relationship between hospitalization and air pollution. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2017;9:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2017.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakonyi S.M.C., Danni-Oliveira I.M., Martins L.C., Braga A.L.F. Air pollution and respiratory diseases among children in Brazil . Rev. Saude Publica / J. Public Heal. 2004;38:5. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102004000500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhate R.S., Loong C.K., Ramakrishna S. Preparation and characterization of nanofibrous filtering media. J. Memb. Sci. 2006;283:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2006.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beal A., Bufato C.A., De Almeida D.S., Squizzato R., Zemiani A., Vernilo N., Batista C.E., Salvador G., Borges D.L.G., Solci M.C., Da Silva A.F., Martins J.A., Martins L.D. Inorganic chemical composition of fine particulates in medium-sized urban areas: A case study of Brazilian cities. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017;17:920–932. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2016.07.0317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y., Wang S., Zhang L., Chen C. Influence of fiber diameter, filter thickness, and packing density on PM2.5 removal efficiency of electrospun nanofiber air filters for indoor applications. Build. Environ. 2020;170 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond T.C., Doherty S.J., Fahey D.W., Forster P.M., Berntsen T., Deangelo B.J., Flanner M.G., Ghan S., Kärcher B., Koch D., Kinne S., Kondo Y., Quinn P.K., Sarofim M.C., Schultz M.G., Schulz M., Venkataraman C., Zhang H., Zhang S., Bellouin N., Guttikunda S.K., Hopke P.K., Jacobson M.Z., Kaiser J.W., Klimont Z., Lohmann U., Schwarz J.P., Shindell D., Storelvmo T., Warren S.G., Zender C.S. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:5380–5552. doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolassi A.C.C., Guerra V.G., Aguiar M.L. Characterization and evaluate the efficiency of different filter media in removing nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017;175:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolassi A.C.C., Nagarajan S., de Araújo Lima B., Guerra V.G., Aguiar M.L., Huon V., Soussan L., Cornu D., Miele P., Bechelany M. Efficient nanoparticles removal and bactericidal action of electrospun nanofibers membranes for air filtration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2019;102:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan C.M., Gardner R.M., Komarek R.J., Gardver R.M., Komarek R.J. Aerobic biodegradation of cellulose acetate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1993;47:1709–1719. doi: 10.1007/s10924-010-0258-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D., Naydich A., Frey M.W., Joo Y.L. Further improvement of air filtration efficiency of cellulose filters coated with nanofibers via inclusion of electrostatically active nanoparticles. Polymer (Guildf). 2013;54:2364–2372. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S., Dey S. Cause-specific premature death from ambient PM2.5 exposure in India: estimate adjusted for baseline mortality. Environ. Int. 2016;91:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbeck I. 1st ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008. Environmental Chemistry of Aerosols. [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.R., Li M., El-Zahab B., Janes M.E., Hayes D., Warner I.M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of β-lactam antibiotic-based imidazolium- and pyridinium-type ionic liquids. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2011;78:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das O., Neisiany R.E., Capezza A.J., Hedenqvist M.S., Försth M., Xu Q., Jiang L., Ji D., Ramakrishna S. The need for fully bio-based facemasks to counter coronavirus outbreaks: a perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida D.S., Duarte E.H., Hashimoto E.M., Turbiani F.R.B., Muniz E.C., de Souza P.Rde S., Gimenes M.L., Martins L.D. Development and characterization of electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers modified by cationic surfactant. Polym. Test. 2020;81:106206. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.106206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Barros P.M., Rodrigues Cirqueira S.S., Aguiar M.L. Evaluation of the deposition of nanoparticles in fibrous filter. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2014;802:174–179. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/msf.802.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dieme D., Cabral-Ndior M., Garçon G., Verdin A., Billet S., Cazier F., Courcot D., Diouf A., Shirali P. Relationship between physicochemical characterization and toxicity of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) collected in Dakar city (Senegal) Environ. Res. 2012;113:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doremalen Nvan, Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt ennifer L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Wit Ede, Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. New England J. Med. Surg. Collat. Branches Sci. 2020;382:0–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang D., Wang Q., Li H., Yu Y., Lu Y., Qian X. Mortality effects assessment of ambient PM 2.5 pollution in the 74 leading cities of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;569–570:1545–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdos M., Cavalett O., Seabra J.E.A., Nogueira L.A.H., Bonomi A. Trends in global warming and human health impacts related to Brazilian sugarcane ethanol production considering black carbon emissions. Appl. Energy. 2013;104:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giannadaki D., Lelieveld J., Pozzer A. Implementing the US air quality standard for PM2.5 worldwide can prevent millions of premature deaths per year. Environ. Heal. A Glob. Access Sci. Source. 2016;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz L.A., Jalvo B., Rosal R., Mathew A.P. Superhydrophilic anti-fouling electrospun cellulose acetate membranes coated with chitin nanocrystals for water filtration. J. Memb. Sci. 2016;510:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.02.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds W.C. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 1999. Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particle. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S.A., Tafreshi H.V. 3-D simulation of particle filtration in electrospun nanofibrous filters. Powder Technol. 2010;201:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2010.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.M., Zhang Y.Z., Kotaki M., Ramakrishna S. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003;63:2223–2253. doi: 10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00178-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Innocentini M.D.de M., Sepulveda P., Ortega Fdos S. Cellular Ceramics: Structure, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Chapter 4.2: permeability; pp. 313–341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen N.A.H., Hoek G., Simic-Lawson M., Fischer P., van Bree L., ten Brink H., Keuken M., Atkinson R.W., Anderson H.R., Brunekreef B., Cassee F.R. Black carbon as an additional Indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1691–1699. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jianyong F., Jianchun Z. Preparation and filtration property of hemp-based composite nonwoven. J. Ind. Text. 2015;45:265–297. doi: 10.1177/1528083714529807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F.J., Fussell J.C. Improving indoor air quality, health and performance within environments where people live, travel, learn and work. Atmos. Environ. 2019;200:90–109. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.11.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M., Brown L., Trought K. Molecular adsorption at particle surfaces: a PM toxicity mediation mechanism. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004;16:99–105. doi: 10.1080/08958370490443187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendouli S., Khalfallah O., Sobti N., Bensouissi A., Avci A., Eskizeybek V., Achour S. Modification of cellulose acetate nanofibers with PVP/Ag addition. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014;28:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2014.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lashof D.A., Ahuja D.R. Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature. 1990 doi: 10.1038/344529a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wen Q., Zhang R. Sources, health effects and control strategies of indoor fine particulate matter (PM2.5): a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;586:610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Liu C., Cheng Y., Guo S., Sun Q., Kan L., Chen R., Kan H., Bai H., Cao J. Association between ambient particulate matter air pollution and ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a case-crossover study in a Chinese city. Chemosphere. 2019;219:724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Yin X., Yu J., Ding B. Electrospun nanofibers for high-performance air filtration. Compos. Commun. 2019;15:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coco.2019.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. Coarse particulate matter and hospitalization for respiratory infections in children younger than 15 years in Toronto: a case-crossover analysis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e235–e240. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T., Wang Hongxia, Wang Huimin, Wang X. The charge effect of cationic surfactants on the elimination of fibre beads in the electrospinning of polystyrene. Nanotechnology. 2004;15:1375–1381. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/15/9/044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Hsu P.C., Lee H.W., Ye M., Zheng G., Liu N., Li W., Cui Y. Transparent air filter for high-efficiency PM 2.5 capture. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Park M., Ding B., Kim J., El-Newehy M., Al-Deyab S.S., Kim H.Y. Facile electrospun Polyacrylonitrile/poly(acrylic acid) nanofibrous membranes for high efficiency particulate air filtration. Fibers Polym. 2015;16:629–633. doi: 10.1007/s12221-015-0629-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Xiao M., Zhang X., Gal C., Chen X., Liu L., Pan S., Wu J., Tang L., Clements-Croome D. A review of air filtration technologies for sustainable and healthy building ventilation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017;32:375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2017.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Löndahl J., Massling A., Pagels J., Swietlicki E., Vaclavik E., Loft S. Size-resolved respiratory-tract deposition of fine and ultrafine hydrophobic and hygroscopic aerosol particles during rest and exercise. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19:109–116. doi: 10.1080/08958370601051677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luginaah I.N., Fung K.Y., Gorey K.M., Webster G., Wills C. Association of ambient air pollution with respiratory hospitalization in a government-designated “area of concern”: the case of Windsor. Ontario. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:290–296. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukáč M., Mrva M., Garajová M., Mojžišová G., Varinská L., Mojžiš J., Sabol M., Kubincová J., Haragová H., Ondriska F., Devínsky F. Synthesis, self-aggregation and biological properties of alkylphosphocholine and alkylphosphohomocholine derivatives of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, cetylpyridinium bromide, benzalkonium bromide (C16) and benzethonium chloride. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;66:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv S., Zhao X., Shi L., Zhang G., Wang S., Kang W., Zhuang X. Preparation and properties of sc-PLA/PMMA transparent nanofiber air filter. Polymers (Basel). 2018;10:1–11. doi: 10.3390/polym10090996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher B.A., Ahmed I.A.M., Karloukovski V., MacLaren D.A., Foulds P.G., Allsop D., Mann D.M.A., Torres-Jardón R., Calderon-Garciduenas L. Magnetite pollution nanoparticles in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016;113:10797–10801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605941113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek N.A.N.N., Ramli N.I. Characterization and antibacterial activity of cetylpyridinium bromide (CPB) immobilized on kaolinite with different CPB loadings. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015;109–110:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2015.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins L.D., Hallak R., Alves R.C., de Almeida D.S., Squizzato R., Moreira C.A.B., Beal A., da Silva I., Rudke A., Martins J.A. Long-range transport of aerosols from biomass burning over Southeastern South America and their implications on air quality. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2018;18:1734–1745. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2017.11.0545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maté T., Guaita R., Pichiule M., Linares C., Díaz J. Short-term effect of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) on daily mortality due to diseases of the circulatory system in Madrid (Spain) Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:5750–5757. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulevicius J., Kliucininkas L., Prasauskas T., Buivydiene D., Martuzevicius D. The comparative study of aerosol filtration by electrospun polyamide, polyvinyl acetate, polyacrylonitrile and cellulose acetate nanofiber media. J. Aerosol Sci. 2016;92:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2015.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Min K., Kim Sookyoung, Kim Sunghwan. Silk protein nanofibers for highly efficient, eco-friendly, optically translucent, and multifunctional air filters. Nat. Sci. Reports. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27917-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira C.A.B., Squizzato R., Beal A., Almeida D.Sde, Rudke A.P., Ribeiro M., Andrade M., de F., Kumar P., Martins L.D. Natural variability in exposure to fine particles and their trace elements during typical workdays in an urban area. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia A., Keppler T., Müller F.A., Vazquez B., Ravegnani F., Monticelli P., Belosi F. Cellulose acetate nanofiber electrospun on nylon substrate as novel composite matrix for efficient, heat-resistant, air filters. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016;153:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2016.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Wang Q., Kan H., Chen R., Wang W. Effects of ambient temperature on daily hospital admissions for mental disorders in Shanghai, China: a time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;590–591:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persano L., Camposeo A., Tekmen C., Pisignano D. Industrial upscaling of electrospinning and applications of polymer nanofibers: a review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013;298:504–520. doi: 10.1002/mame.201200290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puls J., Wilson S.A., Hölter D. Degradation of cellulose acetate-based materials: a review. J. Polym. Environ. 2011;19:152–165. doi: 10.1007/s10924-010-0258-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pun V.C., Manjourides J., Suh H.H. Close proximity to roadway and urbanicity associated with mental ill-health in older adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;658:854–860. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid C.E., Considine E.M., Watson G.L., Telesca D., Pfister G.G., Jerrett M. Associations between respiratory health and ozone and fine particulate matter during a wildfire event. Environ. Int. 2019;129:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert B., Nallathambi G. A concise review on electrospun nanofibres/nanonets for filtration of gaseous and solid constituents (PM2.5) from polluted air. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.colcom.2020.100275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segalin B., Gonçalves F.L.T., Fornaro A. Black carbon em material particulado nas residências de idosos na região metropolitana de São Paulo. Brasil. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2016;31:311–318. doi: 10.1590/0102-778631320150145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld J.H., Pandis S.N. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- Senlin L., Zhenkun Y., Xiaohui C., Minghong W., Guoying S., Jiamo F., Paul D. The relationship between physicochemical characterization and the potential toxicity of fine particulates (PM2.5) in Shanghai atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:7205–7214. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya K.M., Rupakheti M., Shahi A., Maskey R., Pradhan B., Panday A. Near-road sampling of PM2.5, BC, and fine-particle chemical components in Kathmandu Valley. Nepal. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017:6503–6516. doi: 10.5194/acp-17-6503-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shou D., Ye L., Fan J. Gas transport properties of electrospun polymer nanofibers. Polymer (Guildf). 2014;55:3149–3155. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva I., de Almeida D.S., Hashimoto E.M., Martins L.D. Risk assessment of temperature and air pollutants on hospitalizations for mental and behavioral disorders in Curitiba, Brazil. Environ Health. 2020;19(79):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12940-020-00606-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.R. Fuel combustion, air pollution exposure, and health: the situation in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 1993;18:529–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev.eg.18.110193.002525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Zheng L., Lu M., Gui L., Xu D., Wu W., Liu Y. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter pollution on hospital admissions for mental and behavioral disorders: a time-series study in Shijiazhuang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;636:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousan S., Koehler K., Thomas G., Park J.H., Hillman M., Halterman A., Peters T.M. Inter-comparison of low-cost sensors for measuring the mass concentration of occupational aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2016;50:462–473. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2016.1162901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohl A., Aamaas B., Amann M., Baker L.H., Bellouin N., Berntsen T.K., Boucher O., Cherian R., Collins W., Daskalakis N., Dusinska M., Eckhardt S., Fuglestvedt J.S., Harju M., Heyes C., Hodnebrog Hao J., Im U., Kanakidou M., Klimont Z., Kupiainen K., Law K.S., Lund M.T., Maas R., MacIntosh C.R., Myhre G., Myriokefalitakis S., Olivié D., Quaas J., Quennehen B., Raut J.C., Rumbold S.T., Samset B.H., Schulz M., Seland, Shine K.P., Skeie R.B., Wang S., Yttri K.E., Zhu T. Evaluating the climate and air quality impacts of short-lived pollutants. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:10529–10566. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-10529-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana N., Zainal A. Cellulose acetate electrospun nanofibrous membrane: fabrication, characterization, drug loading and antibacterial properties. Bull. Geosci. 2016;39:337–343. doi: 10.1007/s12034-016-1162-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szybist J.P., Song J., Alam M., Boehman A.L. Biodiesel combustion, emissions and emission control. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007;88:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2006.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thenmozhi S., Dharmaraj N., Kadirvelu K., Kim H.Y. Electrospun nanofibers: new generation materials for advanced applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B Solid-State Mater. Adv. Technol. 2017;217:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mseb.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Contal P., Vendel J., Leclerc D., Renaudin V., Penicot P., Thomas D. Modelling pressure drop in hepa filters during dynamic filtration. J. Aerosol Sci. 1999;30:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Vass P., Szabó E., Domokos A., Hirsch E., Galata D., Farkas B., Démuth B., Andersen S.K., Vigh T., Verreck G., Marosi G., Nagy Z.K. Scale-up of electrospinning technology: applications in the pharmaceutical industry. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019:1–24. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J.M., Hobbs P.H. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2005. Atmospheric Sciences: An Introductory Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. Real-time atmospheric monitoring of urban air pollution using unmanned aerial vehicles. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2019;1:79–88. doi: 10.2495/air190081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Yu J.H., Hsieh A.J., Rutledge G.C. Effect of tethering chemistry of cationic surfactants on clay exfoliation, electrospinning and diameter of PMMA/clay nanocomposite fibers. Polymer (Guildf). 2010;51:6295–6302. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Yan Y., Feng J., Zhang J., Deng S., Cai X., Huang L., Xie X., Shi Q., Tan S. Cetylpyridinium bromide/montmorillonite-graphene oxide composite with good antibacterial activity. Biomed. Mater. 2020;15 doi: 10.1088/1748-605x/ab8440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutticharoenmongkol P., Hannirojram P., Nuthong P. Gallic acid-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers as potential wound dressing materials. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019;30:1135–1147. doi: 10.1002/pat.4547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T., Bian Y., Zhang L., Chen C. Relationship between pressure drop and face velocity for electrospun nanofiber filters. Energy Build. 2018;158:987–999. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.10.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y.F., Xu Y.H., Shi M.H., Lian Y.X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016;8:E69–E74. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X., Zhong W., Hao P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63:457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G., Zhao Q., Zhao Y., Yuan Y., Yang Y. The electrospun polyamide 6 nanofiber membranes used as high efficiency filter materials: filtration potential, thermal treatment, and their continuous production. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013;128:1061–1069. doi: 10.1002/app.38211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K.M., Hogan C.J., Matsubayashi Y., Kawabe M., Iskandar F., Okuyama K. Nanoparticle filtration by electrospun polymer fibers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007;62:4751–4759. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2007.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaatari M., Novoselac A., Siegel J. The relationship between filter pressure drop, indoor air quality, and energy consumption in rooftop HVAC units. Build. Environ. 2014;73:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Shim W.S., Kim J. Design of ultra-fine nonwovens via electrospinning of Nylon 6: spinning parameters and filtration efficiency. Mater. Des. 2009;30:3659–3666. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2009.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wen X.Y., Jang C.J. Simulating chemistry-aerosol-cloud-radiation-climate feedbacks over the continental U.S. Using the online-coupled Weather Research Forecasting Model with chemistry (WRF/Chem) Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:3568–3582. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.05.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang S., Yin X., Yu J., Ding B. Slip-effect functional air filter for efficient purification of PM 2.5. Nat. Sci. Reports. 2016;6:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep35472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Han J., Wang F., Shao W., Xiong R., Zhang Q., Pan H., Yang Y., Samal S.K., Zhang F., Huang C. Electrospun nanofibers membranes for effective air filtration. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2017;302:1–27. doi: 10.1002/mame.201600353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Xiong R., Huang C. Bio-based and photocrosslinked electrospun antibacterial nanofibrous membranes for air filtration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;205:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zíková N., Ondráček J., Ždímal V. Size-resolved penetration through high-efficiency filter media typically used for aerosol sampling. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2015;49:239–249. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2015.1020997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]