Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination acceptance is hampered by fears and conflicting attitudes about the need for and safety of vaccine. There are also ethical dilemmas associated with vaccinating adolescents for a sexually transmitted disease despite future cancer risk. The purpose of this research was to determine HPV vaccination acceptance/hesitancy among young adults. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015 data were used. During 2015, 83.1% of adults ages 25–29 years did not receive any HPV vaccination; the UOR was 3.47; 95% CI=2.11, 5.70) compared to adults 18–24 years. There is a need to accelerate public health messaging/campaigns to increase HPV vaccination rates.

Introduction

In 2013–14, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection affected 42.5% of civilian, noninstitutionalized adult Americans, ages 18–59 years[1]. Most infections resolve spontaneously and without complications. However, some lead to HPV-associated cervical cancer (10,800 annually),HPV-associated anal cancer (6,000 annually),HPV-associated oro-pharyngeal cancer (12,900 annually), HPV-associated vulvar/vaginal/penile cancers (4,000 annually), and other conditions [2]. Vaccines havebeen developed to protect against the types of HPV that can cause cancer or genital warts, but the uptake of the vaccines has been uneven across populations[3, 4].

A vaccination series against HPV types 16 and 18 was licensed for females in 2006 and for males in 2009. In 2014, a 9-valent vaccine was approved [5]. The 2019 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended HPV vaccination can be given starting at age 9 [2]. Catch-up vaccination can be given to females through age 26 years and males through age 21 who are not adequately vaccinated [2]. Shared decision-making is recommended for people up to age 45 years [2]. As of 2016, two doses are recommended (0, 6–12 month schedule) for ages 9–14 years (rather than the three doses previously recommended for this age group)[6]. Three doses (0, 1–2, 6 month schedule) are recommended after age 15 years[3]. It is important to understand the factors that influence the vaccine’s acceptance. For adolescents, ages 13–17 years, 54% of females and 49% of males had all recommended doses [3]. The low adherence rates have been attributed to several prevailing myths including perceptions that HPV vaccination is not effective at preventing cancer [7]. Pap smears alone are sufficient to prevent cervical cancer; HPV vaccination is not safe [7]. HPV vaccination is not needed since most infections are naturally cleared by the immune system [7].

The purpose of this research is to identify current behavioral factors in HPV vaccine receipt and adherence in adults 18–29 years. Success of vaccination can be influenced by sudden changes in public consensus [8] (i.e. anti-vaccination movement influence), therefore it is important to know current factors to appropriately target vaccination messaging.

Methods

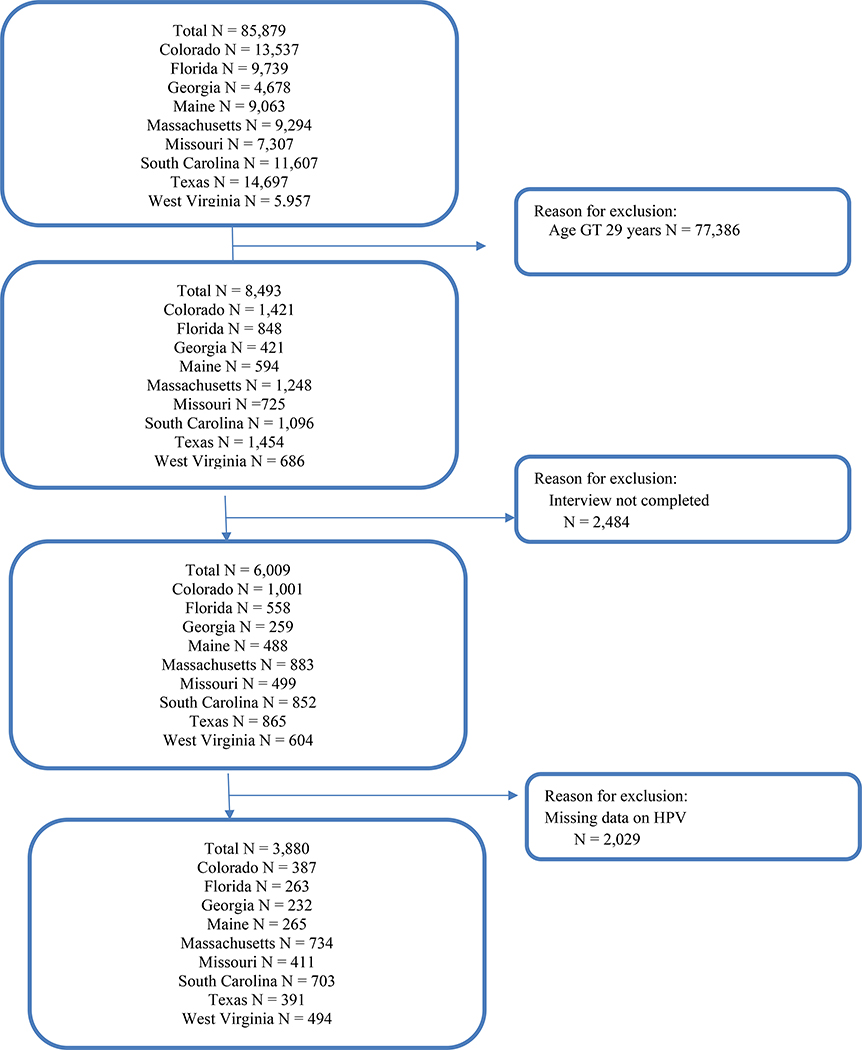

This research was acknowledged by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board as non-human subject research (Protocol number 1910760258). The researchers used a cross-sectional study design of data derived from the Behavioral Risk Factory Surveillance Survey (BRFSS), 2015 Adult Human Papillomavirus Vaccination (optional) modules data used by Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia (Figure 1). BRFSS is an annual, state-based telephone survey in which health and risk data are collected on non-institutionalized adults, ages 18 years and older. The study sample included adults with complete interviews, data on HPV vaccines, and ages 18–29 years (N=3,880) representing 8,683,438 individuals. HPV vaccination receipt and adherence (all recommended HPV doses, 1–2 doses, no doses) were examined by sex, age-group, race/ethnicity, region of domicile; engagement with health behavior (influenza vaccination). The 2016 vaccination schedule to two doses for children, ages 9–14 years, did not apply to these participants; their recommended doses for series completion was 3 doses. We included ages 26 through 29 because of catch-up vaccination[9].

Figure 1.

Study Sample: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015 – Nine States

Results

There were 17.4% (weighted) of participants who had all recommended HPV doses, 12.2% who had 1–2 doses, and 70.4% who had no doses (Table 1). The characteristics of the participants who were more likely to have all recommended HPV doses were: female sex (31.5% versus 4.2%; P <.0001) and those with an annual influenza vaccination (25.0% versus 14.9%; P<.0001). Participants who were less likely to have all recommended HPV doses were African Americans (10.9% versus 21.4%) and Hispanics (13.2% vs 21.4%) as compared to non-Hispanic whites and those living in Southern region as compared to those living in Northeast (15.6% versus 29.7% P <.0001).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by HPV Receipt and Adherence Young Adults (Age 18–29 years) from Nine States Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015

| ALL HPV Doses | 1–2 HPV Doses | No HPV dose | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Wt. % | N | Wt. % | N | Wt. % | Chi-Sq | Prob | |

| ALL | 815 | 427 | 2638 | |||||

| Sex | 148.869 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Female | 703 | 31.5 | 267 | 15.3 | 1061 | 53.3 | ||

| Male | 112 | 4.2 | 160 | 9.3 | 1577 | 86.5 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 15.401 | 0.052 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 624 | 21.4 | 235 | 10.1 | 1703 | 68.6 | ||

| African American | 62 | 10.9 | 76 | 12.2 | 348 | 76.9 | ||

| Hispanic | 68 | 13.2 | 70 | 15.0 | 390 | 71.7 | ||

| Other race | 56 | 18.7 | 36 | 17.3 | 154 | 64.0 | ||

| Missing | 5 | 14.0 | 10 | 14.2 | 43 | 71.9 | ||

| Age Group | 61.323 | 0.000 | ||||||

| 18–24 Years | 535 | 21.6 | 296 | 16.4 | 1276 | 62.0 | ||

| 25–29 Years | 280 | 11.1 | 131 | 5.8 | 1362 | 83.1 | ||

| Influenza Immunizations | 32.521 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Yes, past year | 344 | 25.0 | 157 | 15.1 | 630 | 59.8 | ||

| No | 469 | 14.9 | 267 | 11.0 | 1997 | 74.2 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 3.5 | 3 | 46.3 | 11 | 50.2 | ||

| Region | 40.203 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Northeast | 278 | 29.7 | 120 | 13.0 | 601 | 57.3 | ||

| Midwest | 77 | 18.3 | 39 | 11.0 | 295 | 70.7 | ||

| South | 380 | 15.6 | 218 | 12.3 | 1485 | 72.1 | ||

| West | 80 | 21.3 | 50 | 10.2 | 257 | 68.5 | ||

Note: Based on 3,880 young adults in the age group 18–29 years from nine states and who did not have missing values in human papillomavirus vaccination variable. Significant group differences were tested with Rao-Scott chi-squares.

HPV: Human Papillomavirus Vaccination

Females had an unadjusted odds ratio (UOR) 4.85 [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.47, 9.53; P< .0001) compared with males for all recommended HPV doses. As compared with non-Hispanic white upon all recommended HPV doses, the UOR for non-Hispanic black was 0.39 [95%CI: 0.16, 0.97; P<.05 ) and the UOR for Hispanics was 0.47 [95%CI: 0.23, 0.99; P<.05 ). An overwhelming majority (83.1%) of adults in the age group 25–29 years did not receive any HPV vaccination; the UOR was 3.47; 95% CI= 2.11, 5.70; P<.05 ) as compared to adults in the age group 18–24 years.

Discussion

The CDC predicts that approximately 80% of the population will have an HPV infection[9]. However, HPV vaccination is an effective intervention with the potential to reduce cervical cancer by 90% and other HPV-related cancers by 50% worldwide[10]. Although there has been an increase in the percentage of adolescents who have started the HPV series, 51% have not completed the recommended doses[9], and there is limited information concerning adults. In this study of adults, ages 18–45 years, there were 8.9% who reported having all recommended doses of HPV vaccine. In a survey of adult women, ages 18–26 years, 10% responded that they had initiated HPV vaccination[4]. In that study, initiating the HPV vaccination series was influenced by having medical insurance, living at or above 200% of the federal poverty level, not being married, and having received vaccination for hepatitis B in the survey [4]. In 2009, the cost of one dose for people who did not have insurance was $120, which could have been a barrier to access, particularly to people below 200% of the federal poverty level [4]. Increased risk perception may have influenced more unmarried women to seek HPV vaccination; and, healthful practices, such as receiving other recommended vaccinations may have influenced decisions to initiate HPV vaccination[4].

There are several limitation worth noting. The data were based on self-report therefore lacking information about a known practice visit or the practice infrastructure. For adolescents there is an issue of stocking availability of the vaccine in primary care clinics influencing whether a provider will recommend a booster dose[11]. However, in another study, issues of insurance and other financial barriers were more prominent, as 71% of the physician respondents had adequate supplies of the vaccine [12].

As there are serious consequences that can develop following HPV infection [2], HPV vaccination initiation and completion remain significant public health goals. Efforts are necessary to increase vaccination rates for eligible adults. Providers are requested to bundle recommendations with other vaccinations, provide a consistent messaging, use every opportunity to vaccinate, provide personal examples, and answer questions effectively[9]. In this research, targeting messages specifically to males, and regions beyond the Northeast may improve vaccination uptake.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios (UOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) of HPV Receipt and Adherence (Reference = “1–2 HPV Doses) Young Adults (Age 18–29 years) from Nine States Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015

| ALL HPV Doses | NO HPV Dose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UOR | 95% CI | Sig | UOR | 95% CI | Sig | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 4.85 | [2.47, 9.53] | *** | 0.41 | [0.26, 0.67] | *** |

| Male (Ref) | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | ||||||

| African American | 0.39 | [0.16, 0.97] | * | 0.79 | [0.44, 1.42] | |

| Hispanic | 0.47 | [0.23, 0.99] | * | 0.73 | [0.41, 1.29] | |

| Other Race | 0.42 | [0.14, 1.24] | 0.49 | [0.17, 1.42] | ||

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18–24 Years (Ref) | ||||||

| 25–29 Years | 1.30 | [0.73, 2.30] | 3.47 | [2.11, 5.70] | *** | |

| Influenza Immunizations | ||||||

| Yes, past year | 0.92 | [0.52, 1.61] | 0.53 | [0.32, 0.87] | * | |

| No (Ref) | ||||||

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | ||||||

| Midwest | 0.72 | [0.45, 1.14] | 1.32 | [0.90, 1.93] | ||

| South | 0.55 | [0.38, 0.80] | ** | 1.27 | [0.95, 1.71] | |

| West | 0.80 | [0.49, 1.31] | 1.41 | [0.94, 2.10] | ||

Note: Based on 3,880 young adults in the age group 18–29 years from nine states and who did not have missing values in human papillomavirus vaccination variable. Significant group differences were tested with Rao-Scott chi-squares. UORs and 95% Cis are from unadjusted multinomial logistic regression on HPV receipt and adherence.

HPV: Human Papillomavirus Vaccination

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5U54GM104942-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM104942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data Statement

Data for this study are publicly available Behavioral Risk Factory Surveillance Survey (BRFSS), 2015 data available online at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2015.html.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McQuillan GM, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, Unger ER, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. Report No.: NCHS data brief, no 280. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. American Journal of Transplantation. 2019;19(11):3202–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Mbaeyi SA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(33):909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain N, Euler GL, Shefer A, Lu P, Yankey D, Markowitz L. Human papillomavirus (HPV) awareness and vaccination initiation among women in the United States, National Immunization Survey—Adult 2007. Preventive Medicine. 2009;48(5):426–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrosky E, Bocchini JA Jr, Hariri S, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, et al. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015;64(11):300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meites E Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016;65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bednarczyk RA. Addressing HPV vaccine myths: practical information for healthcare providers. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2019;15(7–8):1628–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habel MA, Liddon N, Stryker JE. The HPV vaccine: a content analysis of online news stories. Journal of women’s health. 2009;18(3):401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Schedule and Dosing 2019. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/schedules-recommendations.html.

- 10.de Sanjosé S, Serrano B, Tous S, Alejo M, Lloveras B, Quirós B, et al. Burden of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers attributable to HPVs 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52 and 58. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2019;2(4):pky045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornides ML, Calo WA, Heisler-MacKinnon JA, Gilkey MB. US primary care clinics’ experiences during introduction of the 9-valent HPV vaccine. Journal of community health. 2018;43(2):291–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soon R, Cruz MRID, Tsark JU, Chen JJ, Braun KL. A Survey of Physicians’ Attitudes and Practices about the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine in Hawai ‘i. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health. 2015;74(7):234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]