Abstract

Background

Neurologic injury and cognitive disorder after cardiac surgery are associated with morbidity and mortality. Variability in the application of neuroprotective strategies likely exists during cardiac surgery. The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) conducted a survey amongst its members on common perioperative neuroprotective strategies: assessment of aortic atheromatous burden, management of intraoperative blood pressure, and use of cerebral oximetry.

Methods

A 15-item survey was developed by three members of the SCA Continuous Practice Improvement - Cerebral Protection Working Group. The questionnaire was then circulated amongst all working group members, adapted, and tested for face validity. On March 26, 2018, the survey was sent to members of the SCA via email using the Research Electronic Data Capture system. Responses were recorded until April 16, 2018.

Results

Of the 3645 surveys emailed, 526 members responded (14.4%). Most responders worked in academic institutions (58.3%), followed by private practices (38.7%). Epi-aortic ultrasound for the assessment of aortic atheromatous burden was most commonly utilized at the surgeon’s request (46.5%). Cerebral oximetry was most commonly used in patients with increased perioperative risk of cerebral injury (41.4%). Epi-aortic ultrasound (1.9%), and cerebral oximetry (5.2%) were rarely part of a standardized monitoring approach.

A majority of respondents (52.0%), reported no standardized management strategies for neuroprotection during cardiac surgery at their institution. 55.3% stated that no standardized institutional guidelines were in place for managing a patient’s blood pressure intraoperatively or during cardiopulmonary bypass. When asked about patients at risk for postoperative cerebral injury, 41.3% targeted a blood pressure goal >65 mmHg during cardiopulmonary bypass. The majority of responders (60.4%) who had access to institutional rates of postoperative stroke/cerebral injury had standard neuroprotective strategies in place.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that approximately half of respondents to this SCA survey do not use standardized guidelines/standard operating procedures for perioperative cerebral protection. The lack of standardized neuroprotective strategies during cardiac surgery may impact postoperative neurologic outcomes. Further investigations are warranted, and should assess the association of standardized neuroprotective approaches and postoperative neurological outcomes.

Introduction

Neurological complications such as cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) and perioperative cognitive disorders (PCD) after cardiac surgery are associated with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality, reduced quality of life, and greater resource utilization.1,2 The incidence of CVA after cardiac surgery ranges from 1.6–5.7%, while the incidence of PCD can be as high as 53% at discharge.3–6 The etiology of neurologic complications after cardiac surgery is wide-ranging and includes cerebral hypoperfusion, anemia, high cerebral oxygen consumption, with perioperative embolic events originating most commonly from the thoracic aorta.2,7,8,9

Perioperative neuroprotective strategies during cardiac surgery aimed at assessing and modifying associated risk factors are also wide-ranging. Commonly performed methods focus on oxygen and glucose delivery by optimizing cerebral perfusion, minimizing cerebral oxygen consumption via sedation and hypothermia, and optimizing oxygen carrying capacity during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).10,11 There remains ongoing debate, however, about the most appropriate target blood pressure, temperature, and hematocrit.12–14 Aortic atheromatous burden can be assessed using either transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or epi-aortic ultrasound.8,15 Despite reasonable evidence that epi-aortic ultrasound is accurate for the assessment of atheromatous burden, there is significant variability in the utilization of epi-aortic ultrasound and/or TEE.12–14,16 Moreover, emerging technologies, including cerebral oximetry (near-infrared-spectroscopy) and bispectral index monitoring (BIS), aimed at detecting cerebral ischemia, have not been universally adopted in cardiac surgery.2,17,18 Other strategies aim to minimize aortic manipulation, such as off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and single-clamping of the aorta (cross-clamp only, no side-clamp for proximal anastomosis). There remains considerable variability between institutions and even between care teams within the same institution, mainly because of uncertainty whether these strategies provide benefits in regards to neurologic outcomes.19,20

In order to describe current patterns of neuroprotective techniques among Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) members during cardiac surgery, the SCA Continuous Practice Improvement (CPI) - Cerebral Protection Working Group set out to design and administer a survey. Chosen topics included: first, Here, we aimed to characterize current practice patterns of neuroprotective strategies and management amongst the SCA membership for assessment of aortic atheromatous burden, management of intraoperative blood pressure, and use of cerebral oximetry during cardiac surgery. Further, we hypothesized that responses may vary if standardized neuroprotective techniques were in place.

Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Participants gave consent by participation in the survey according to the Institutional Review Board approval. To indicate this, the following statement was included in the introductory letter (Supplement 1): “By completing the survey, you are agreeing to participate in this research study”. This survey study was performed adhering to the applicable guideline: Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys).21

Members of the SCA CPI - Cerebral Protection Working Group rank-ordered the following ten topics related to perioperative cerebral protection during cardiac surgery: 1. Atheromatous aortic burden, 2. Cerebral monitoring with cerebral oximetry or bispectral index monitoring, 3. Intraoperative blood pressure management, 4. Intraoperative temperature management 5. Intraoperative glucose management, 6. Sedation, 7. Hematocrit, 8. Pharmacologic therapies, 9. Postoperative stroke detection and management, and 10. Delirium prevention, detection, and management. Based on published literature and their expertise, the working group chose to prioritize intraoperative ultrasound assessment of aortic atheromatous burden, intraoperative blood pressure management, and cerebral monitoring using cerebral oximetry. Then, three members of the working group developed a 15-item survey. This draft survey was circulated amongst all working group members and tested for face validity: we asked working group members to comment if instrument items were appropriate to the targeted assessment of current neuroprotective approaches utilized by SCA members and at their institutions.22 As the final step to assess face validity, the revised survey was sent to a second group of 46 experts in the field of perioperative neuroprotection that had been suggested by the members of SCA working group. Again, their comments were used to further modify the survey to assure face validity amongst the target population. The final survey contained 14 multiple-choice questions and one comment section in order to permit optional messages to the study team (Supplement 1). The first part asked for basic demographic and institutional information, the second pertained to the assessment of aortic atheroma during cardiac surgery, the third inquired about clinical management of arterial blood pressure during cardiac surgery, and the final part referred to perioperative cerebral oximetry during cardiac surgery and concluded with a free text comment section. When indicated, all answers that applied could be chosen. A “back button” allowed responders to review or change their responses. The usability and technical functionality of the electronic questionnaire was tested by the working group members before the survey was sent out to the SCA membership.

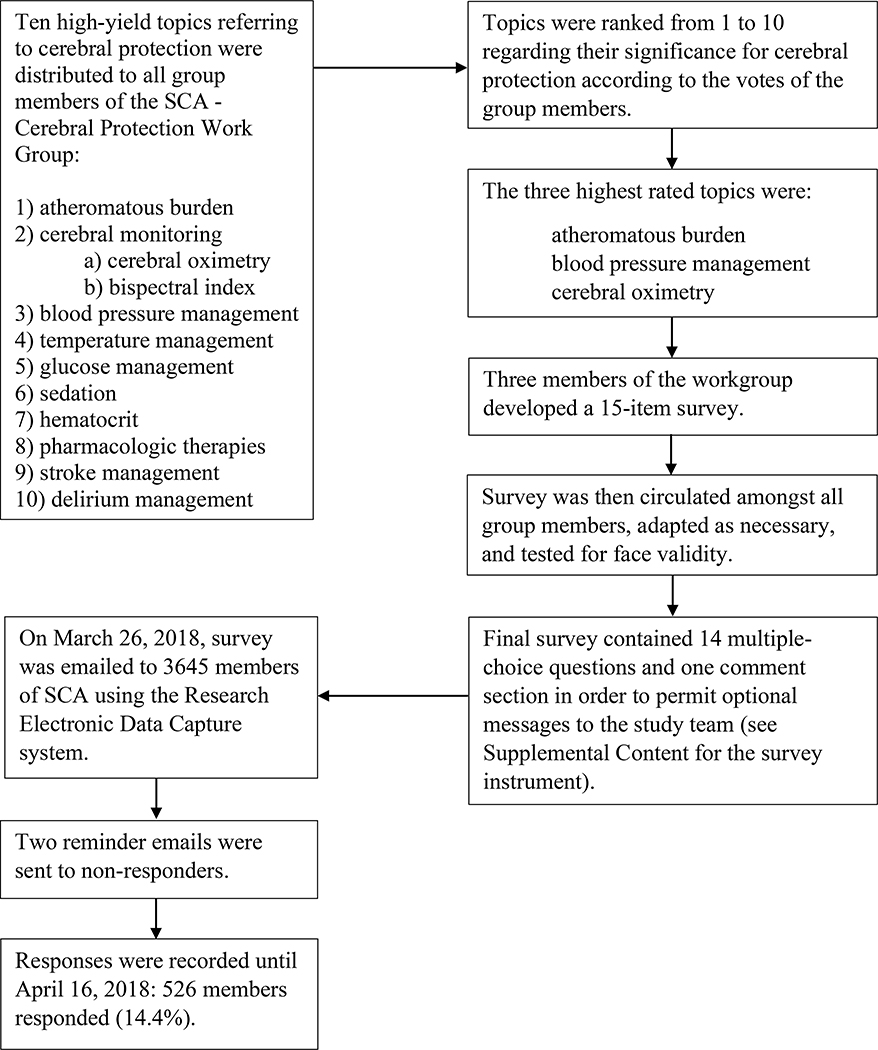

On March 26, 2018, the finalized survey was emailed to 3,645 members of the SCA. Study data were collected and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools.23 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. Participation was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. Each member received a unique survey link eliminating the possibility for duplicate answers. After the initial email, two reminder emails were sent to non-responders. Responses were recorded until April 16, 2018. All surveys, including incomplete questionnaires, were analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow sheet describing establishment, testing, submission, and data recording of survey. SCA: Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists.

Statistical Analysis

SCA members with valid email addresses on file were included in this survey. Responses were summarized using descriptive statistics. Univariate comparisons of demographic characteristics were made between respondents who reported the presence of standardized management strategies/standard operating procedures for cerebral protection during cardiac surgery (either for all cardiac surgical patients, patients at increased risk for perioperative cerebral injury, or based on surgeon preference) versus all others who had also answered the relevant demographic characteristic question using the Pearson Chi-Square test (exact 2-sided significance). We used the Clopper-Pearson method to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) to characterize proportions and error bars on the bar graphs. Proportions and bar graphs were based on the actual number of responses given to each specific question. Based on previous approaches used for survey research of the SCA membership, we assumed that 501 responses were required to achieve a global margin of error of 4% with estimates for the membership population at 3,000, confidence interval of 95%, and a sample proportion of 0.5.24 SPSS, Version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 3,645 surveys emailed, 526 members responded (14.4%). 90.7% of the submitted surveys were filled out completely.

Detailed information about member characteristics is listed in Table 1. If information on institutional rates of postoperative stroke/cerebral injury were provided to responders in detail, 60.4% [95% CI 50.4–69.7%] had standard operating procedures in place.

Table 1:

Sample characteristics. Comparisons were made between those who reported the presence of standardized treatment strategies/standard operating procedures for cerebral protection during cardiac surgery vs. all others in the respective line using Pearson Chi-Square test (exact 2-sided significance). For questions with the option for multiple answers (*), comparisons were made for each answer option; for questions that permitted only one answer option, global comparisons were made for all answer options.

| Characteristic (# of responses) | Frequency (%) | 95% Confidence Interval (%) | Standardized Treatment / Standard Operating Procedures |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO or unknown (%) | 95% Confidence Interval (%) | YES (%) | 95% Confidence Interval (%) | ||||

| I work...* (496) | |||||||

| ...at an academic institution | 289 (58.3) | 53.8–62.6 | 150 (51.9) | 46.0–57.8 | 139 (48.1) | 42.2–54.0 | 0.143 |

| ...in private practice | 192 (38.7) | 34.4–43.2 | 114 (59.4) | 52.1–66.4 | 78 (40.6) | 33.6–47.9 | 0.116 |

| ...at a government institution | 57 (11.5) | 8.8–14.6 | 27 (47.4) | 34.0–61.0 | 30 (52.6) | 39.0–66.0 | 0.259 |

| ...other | 8 (1.6) | 0.7–3.2 | 4 (50.0) | 15.7–84.3 | 4 (50.0) | 15.7–84.3 | 1.000 |

| I work...* (498) | |||||||

| ...in North America | 404 (81.1) | 77.4–84.5 | 228 (56.4) | 51.4–61.3 | 176 (43.6) | 38.7–48.6 | 0.137 |

| ...in Oceania | 34 (6.8) | 4.8–9.4 | 22 (64.7) | 46.5–80.3 | 12 (35.3) | 19.7–53.5 | 0.285 |

| ...in Europe | 35 (7.0) | 4.9–9.6 | 14 (40.0) | 23.9–57.9 | 21 (60.0) | 42.1–76.1 | 0.079 |

| ...in Asia | 17 (3.4) | 2.0–5.4 | 5 (29.4) | 10.3–56.0 | 12 (70.6) | 44.0–89.7 | 0.045 |

| ...in South/Central America | 10 (2.0) | 1.0–3.7 | 5 (50.0) | 18.7–81.3 | 5 (50.0) | 18.7–81.3 | 1.000 |

| ...in Africa | 1 (0.2) | 0.0–1.1 | 1 (100.0) | 2.5–100.0 | 0 (0) | 0–97.5 | 1.000 |

| My role is...* (497) | |||||||

| ...Anesthesiologist | 472 (95.0) | 92.7–96.7 | 259 (54.9) | 50.3–59.4 | 213 (45.1) | 40.6–49.7 | 1.000 |

| ...Intensivist | 62 (12.5) | 9.7–15.7 | 31 (50.0) | 37.0–63.0 | 31 (50.0) | 37.0–63.0 | 0.416 |

| ...Surgeon | 1 (0.2) | 0–1.1 | 0 (0) | 0–97.5 | 1 (100.0) | 2.5–100.0 | 0.451 |

| ...Resident/Fellow | 32 (6.4) | 4.4–9.0 | 14 (43.8) | 26.4–62.3 | 18 (56.2) | 37.7–73.6 | 0.203 |

| ...other | 2 (0.4) | 0–1.4 | 2 (100.0) | 15.8–100.0 | 0 (0) | 0–84.2 | 0.504 |

| My practice performed ... open heart procedures in 2016 (498) | 0.114 | ||||||

| <200 | 75 (15.1) | 12.0–18.5 | 38 (50.7) | 38.9–62.4 | 37 (49.3) | 37.6–61.1 | |

| 200–500 | 155 (31.1) | 27.1–35.4 | 87 (56.1) | 47.9–64.1 | 68 (43.9) | 35.9–52.1 | |

| 500–1,000 | 127 (25.5) | 21.7–29.6 | 79 (62.2) | 53.2–70.7 | 48 (37.8) | 29.3–46.8 | |

| >1,000 | 136 (27.3) | 23.4–31.4 | 65 (47.8) | 39.2–56.5 | 71 (52.2) | 43.5–60.8 | |

| I don’t know | 5 (1.0) | 0.3–2.3 | 4 (80.0) | 47.8–100.0 | 1 (20.0) | 0–52.2 | |

| Information on institutional rates of postoperative stroke/cerebral injury is ... (496) | <0.001 | ||||||

| ...available to me in detail | 106 (21.4) | 17.8–25.2 | 42 (39.6) | 30.3–49.6 | 64 (60.4) | 50.4–69.7 | |

| ...somewhat available to me | 248 (50.0) | 45.5–54.5 | 137 (55.2) | 48.8–61.5 | 111 (44.8) | 38.5–51.2 | |

| ...not at all available to me | 142 (28.6) | 24.7–32.8 | 92 (64.8) | 56.3–72.6 | 50 (35.2) | 27.4–43.7 | |

Regarding organized institution efforts to standardize care to reduce the incidence of postoperative cardiac surgical stroke and cerebral injury, 37.8% or responders [95% CI 33.5–42.3%] answered yes, 43.7% [95% CI 39.3–48.1%] no, and 18.5% [95% CI 15.2–22.2%] did not know.

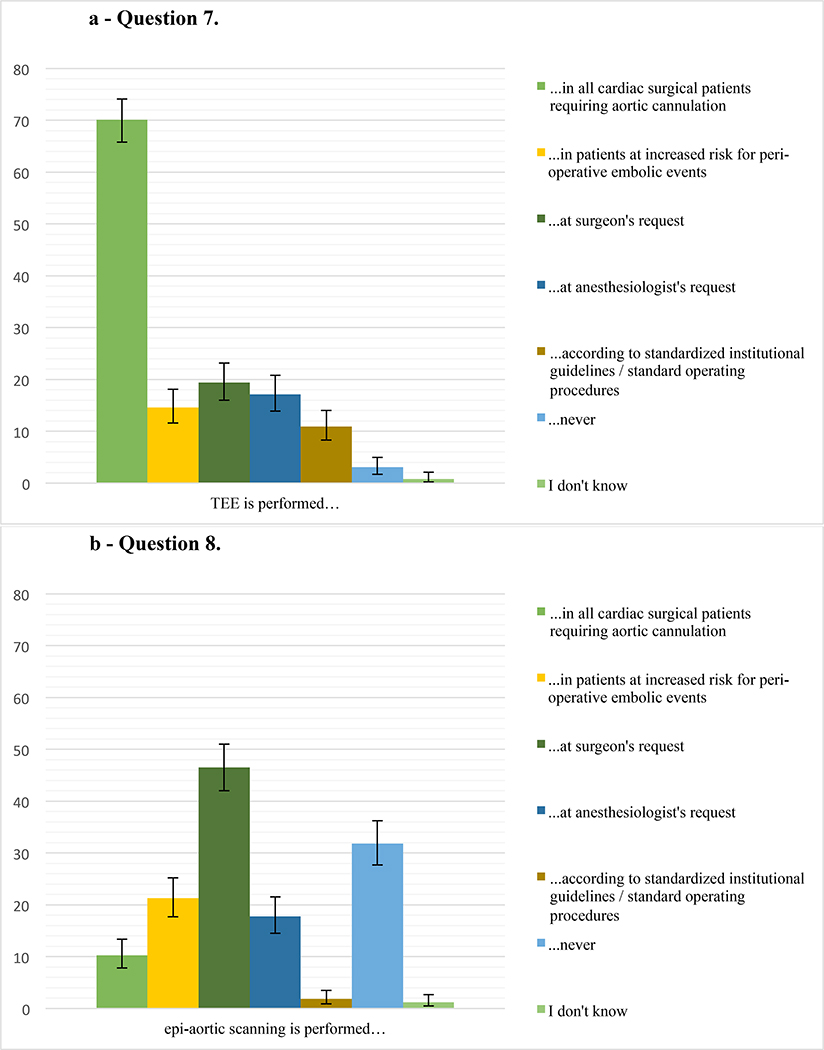

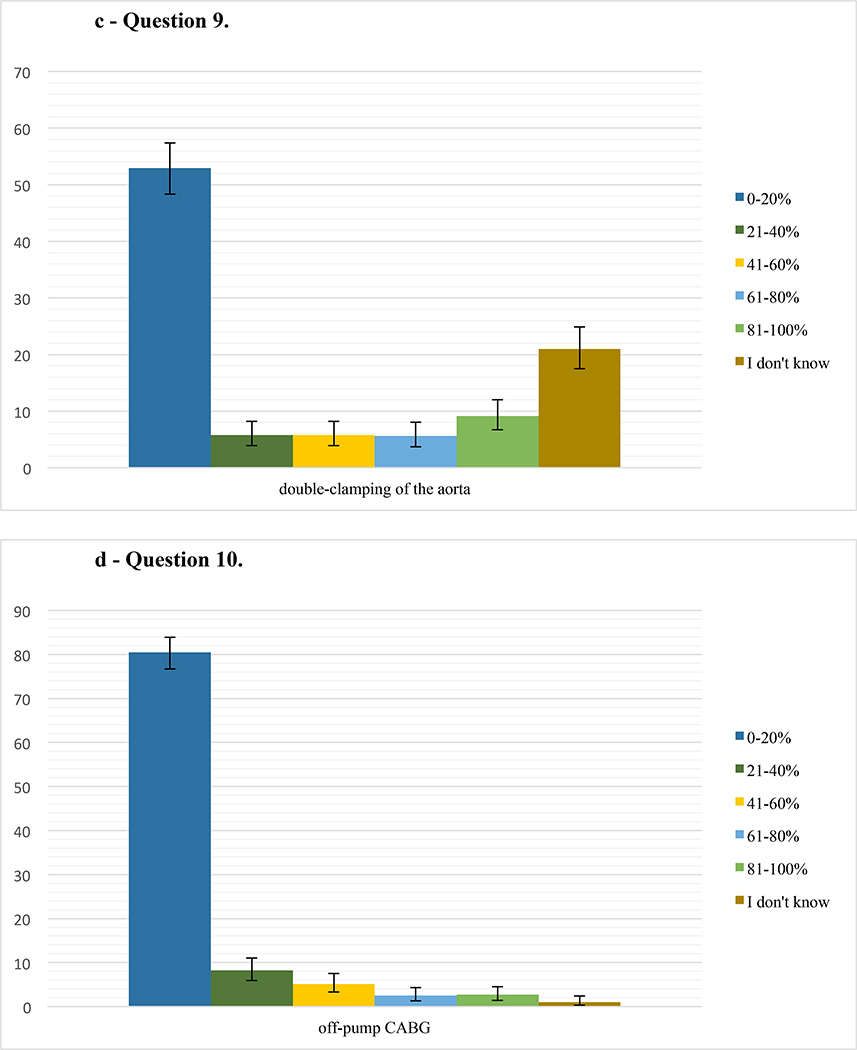

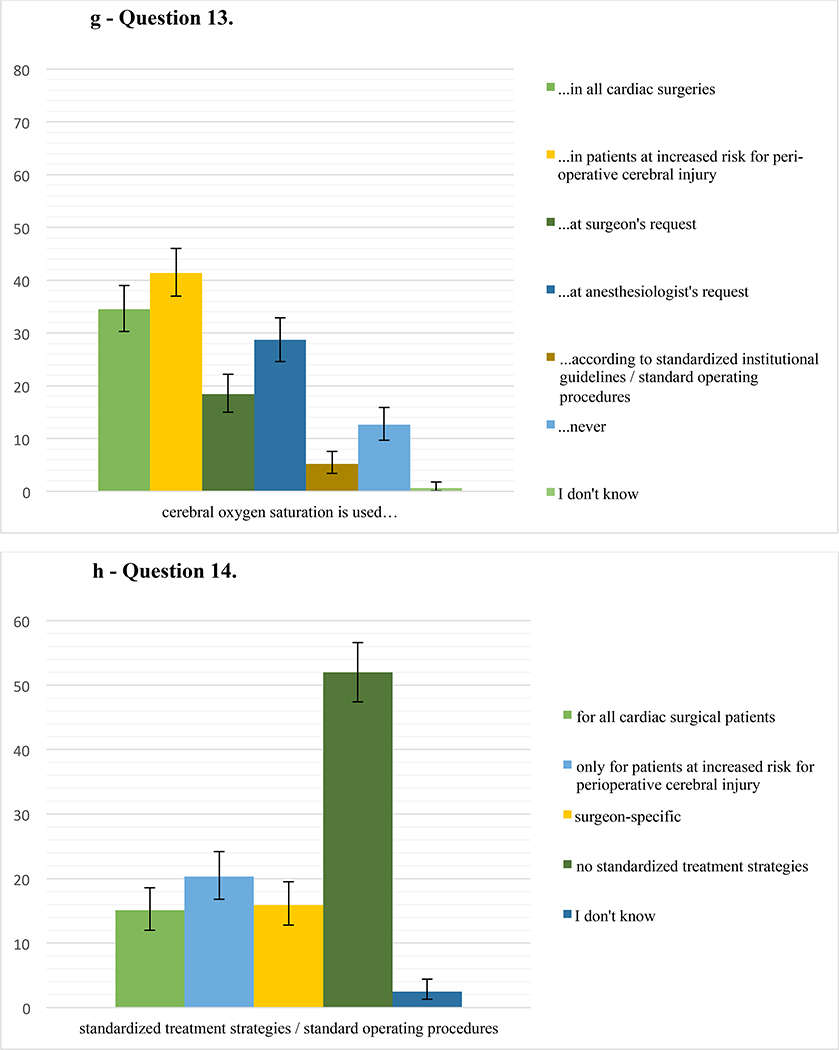

Responses for the questions 7–14 on the topics atheromatous burden, aortic manipulation, intraoperative blood pressure management, cerebral oximetry, and standardization of neuroprotective management during cardiac surgery are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

a – Question 7. Percentage of respondents (485 responses) who perform transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in their practice in either all cardiac surgical patients requiring aortic cannulation, in patients at increased risk for perioperative cerebral injury, at the surgeon’s request, at the anesthesiologist’s request, as part of standardized institutional guidelines/standard operating procedures, never, or who do not know the answer (choose all that apply). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

b – Question 8. Percentage of respondents (484 responses) who perform epi-aortic scanning, in their practice in either all cardiac surgical patients requiring aortic cannulation, in patients at increased risk for perioperative cerebral injury, at the surgeon’s request, at the anesthesiologist’s request, as part of standardized institutional guidelines/standard operating procedures, never, or who do not know the answer (choose all that apply). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

c – Question 9. Percentage of respondents (486 responses) who perform double-clamping of the aorta during Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) in their practice in either 0–20%, 21–40%, 61–80%, or 81–100% of CABG surgeries, or who do not know the answer. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

d – Question 10. Percentage of respondents (487 responses) who perform off-pump technique during Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) in their practice in either 0–20%, 21–40%, 61–80%, or 81–100% of CABG surgeries, or who do not know the answer. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

e – Question 11. Percentage of respondents (479 responses) who have standardized institutional guidelines/standard operating procedures in place for managing patients’ blood pressure either intraoperatively excluding cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), during CPB, depending on the surgeon’s preference, only in high-risk patients, or have no guidelines/procedures in place. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

f – Question 12. Percentage of respondents (482 responses) who routinely target a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of either >45 mmHg, >55 mmHg, >65 mmHg, >75 mmHg, >85 mmHg, according to a goal-directed algorithm, or do not target a specific MAP during cardiopulmonary bypass for patients thought to be at risk for postoperative cerebral injury. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

g – Question 13. Percentage of respondents (478 responses) who use cerebral oxygen saturation monitoring in their practice in either all cardiac surgeries, in patients at increased risk for perioperative cerebral injury, at the surgeon’s request, at the anesthesiologist’s request, as part of standardized institutional guidelines/standard operating procedures, never, or who do not know the answer (choose all that apply). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

h – Question 14. Percentage of respondents (477 responses) who have standardized management strategies/standard operating procedures in place for cerebral protection during cardiac surgery in their institution (choose all that apply) either for all cardiac surgical patients, for patients at increased risk for perioperative cerebral injury, depending on the surgeon, who do not have standardized management strategies, or do not know the answer. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

The results of our survey suggest noteworthy variability among SCA members in certain approaches to assess and prevent perioperative neurologic injury during cardiac surgery. The majority of members surveyed had no standard operating procedures in place during cardiac surgery for cerebral protection or blood pressure management. Less than half of respondents identified institutional efforts to standardize neurologic assessment and neuroprotective strategies in cardiac surgery. While a vast majority use TEE for all cardiac cases, TEE, epi-aortic ultrasound, cerebral oximetry, intraoperative blood pressure management, or blood pressure management during CPB are rarely part of standardized guidelines. Of all respondents, less than a quarter answered that institutional information on postoperative rates of strokes/cerebral injury is available to them in detail. There was an association between presence of some degree of standard neuroprotective strategies and information on institutional rates of postoperative stroke/cerebral injury. Further, respondents practicing in Asia were more likely to have standard operating procedures in place, however, this geographic region represented only 17 participants.

To our knowledge, this is the first formal survey of cardiac anesthesiologists from a professional society demonstrating considerable standardization in the assessment of aortic atheroma, blood pressure management, and the use of cerebral oximetry during cardiac surgery. As CVA and PCD remain common and significant complications following cardiac surgery, standardization and bundling of interventions for neuroprotection could potentially improve neurologic outcome and, therefore, should be studied further.

Aortic Atheromatous Burden

Our survey showed that while a majority of respondents uses TEE for all cardiac surgeries requiring aortic cannulation, only a minority uses epi-aortic ultrasound, which is recommended for evaluating the atheromatous burden in the ascending thoracic aorta.16,25 Our findings, therefore, correlate with existing literature, which has described barriers to routine utilization of epiaortic ultrasound in the past.16 According to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, only 13% of CABG surgeries nationwide were performed off-pump in 2016;26 and our results corroborate these data. We speculate that the practice of utilizing CPB may be related to no clear improvement in stroke rates and concerns in regards to long-term outcomes after off-pump surgery.20,27 A large, propensity-matched study, which compared the use of single versus double aortic clamping during the proximal anastomosis of a CABG showed no difference in stroke rate or mortality.19 The results of our survey suggest a preference for single-clamping or aorta, since most reported utilizing a double-clamp technique in less than 20% of CABG surgeries.

Blood Pressure

The results of our survey also suggest considerable variability in targeted blood pressure during CPB. Most responders prefer to aim for a mean arterial pressure (MAP) >65 mmHg. While perioperative hypotension is likely an important modifiable risk factor for adverse neurologic outcomes during cardiac surgery, the published literature remains somewhat equivocal. A large retrospective, propensity-adjusted trial demonstrated an independent association between stroke and sustained MAP <64 mmHg during CPB.28 A randomized controlled trial, however, showed no difference in new cerebral lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging in patients with a MAP goal of 40–50 mmHg compared to 70–80 mmHg during CPB.12 It stands to reason that large fluctuations in blood pressure above and below the patient’s respective limits of cerebral autoregulation would be associated with stroke after cardiac surgery.7,29 Indeed, optimizing MAP to be greater than an individual patient’s lower limit of cerebral autoregulation during CPB may reduce the incidence of delirium after cardiac surgery.30

Cerebral Oximetry

Most commonly, cerebral oximetry was reported as used in high-risk patients for cerebral injury. Cerebral oximetry is a non-invasive and user-friendly form of estimating brain tissue oxygen saturation.18 In a systematic review, however, results remain equivocal regarding its ability to prevent neurologic complications such as CVA and PCD.31

Respondents with different degrees of access to institutional rates of postoperative stroke/cerebral injury also varied in regards to reporting the presence of standard operating procedures. Current expertand society guidelines for neuroprotective measures are based on lower levels of evidence and emphasize the need for well-designed randomized controlled trials.2,32,33 However, the American Heart Association suggests that standardized outcome reporting is an essential step toward improving evidence-based care in cardiac surgery as it allows generation of results and comparison of findings across different institutions and trials.34 We, therefore, propose that institutional reporting on neurologic outcome is a valuable first step in standardizing efforts geared towards neuroprotection.

Our study has several limitations. First, our survey was only sent out to members of one professional society, which restricts external validity. However, since SCA is an international organization, our sample size also included 18.9% of members not practicing in North America including participants from Europe, Oceania, Asia, Africa, Central and South America [Table 1]. Indeed, the demographic concentration of our sample in North America appears to represent the SCA membership appropriately. Based on Reves et al., only 20% of the SCA members are from countries other than the United States.35 Second, our study had a response rate of 14.4%, possibly introducing non-response bias. Nonetheless, typical response rates from physicians to online surveys range from 10–13%, and a higher response rate does not necessarily improve non-response bias in regards to demographic and practice variables.36–38 Further, our study did not include other relevant components of neuroprotection, such as transcranial Doppler, conventional or processed electroencephalogram, or preoperative identification of patients at risk for CVA and PCD, which could affect content validity.10,18,39,40 In the interest of focus and perceived relevance, the working group prioritized the assessment of atheromatous aortic burden, blood pressure management, and cerebral oximetry as the three most pertinent topics to neurocognitive health in cardiac surgical patients.7,8,18,29,31

Conclusion

The results of this survey suggest considerable variability among a fraction of the SCA membership regarding neuroprotective practices during cardiac surgery. The lack of standardized neuroprotective strategies is likely related to equivocal evidence behind most neuroprotective strategies, but may, nevertheless, adversely impact our understanding of postoperative neurologic outcomes. Further studies on clinical outcomes following standardizing and bundling of neuroprotective measures are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

How often do members of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists use standardized neuroprotection strategies?

Findings

Of 526 members, who responded to the survey, 52.0% of respondents reported no standardized management strategies for neuroprotection during cardiac surgery at their institution.

Meaning

Standardized neuroprotective strategies during cardiac surgery are uncommon, and further investigation should assess their association with postoperative neurological outcomes.

Acknowledgement

This work was initiated as part of the Continuous Practice Improvement - Cerebral Protection Working Group of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists.

Financial Disclosures: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Award Number K23DA040923 to Karsten Bartels and by NIH Grant Number UL1 TR002535. The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The NIH had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Glossary of Terms

- CVA

cerebrovascular accident

- PCD

perioperative cognitive disorder

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

- BIS

bispectral index

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- SCA

Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

- CPI

Continuous Practice Improvement

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- CI

confidence interval

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Tjörvi E. Perry is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA) and is a member of the Medical Advisory Boards for the Improvement of Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring in Cardiac Surgical Patients. Otherwise the authors report no conflicts of interest.

Clinical trial number and registry URL: not applicable

References

- 1.Gasparovic H, Kopjar T, Rados M et al. Impact of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning Preceding Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting on Inducing Neuroprotection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger M, Schenning KJ, Brown CHt et al. Best Practices for Postoperative Brain Health: Recommendations from the Fifth International Perioperative Neurotoxicity Working Group. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1406–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craver JM, Puskas JD, Weintraub WW et al. 601 Octogenarians Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: Outcome and Comparison with Younger Age Groups. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Neurocognitive Function after Coronary-Artery Bypass Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarakji KG, Sabik JF 3rd, Bhudia SK et al. Temporal Onset, Risk Factors, and Outcomes Associated with Stroke after Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. JAMA. 2011;305:381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartels K, McDonagh DL, Newman MF et al. Neurocognitive Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganushchak YM, Fransen EJ, Visser C et al. Neurological Complications after Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Related to the Performance of Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Chest. 2004;125:2196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abah U, Large S. Stroke Prevention in Cardiac Surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:155–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartels K, Li YJ, Li YW et al. Apolipoprotein Epsilon 4 Genotype Is Associated with Less Improvement in Cognitive Function Five Years after Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:618–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salameh A, Dhein S, Dahnert I et al. Neuroprotective Strategies During Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazzeri C, Bevilacqua S, Ciappi F et al. Glucose Metabolism in Cardiovascular Surgery. HSR Proc Intensive Care Cardiovasc Anesth. 2010;2:19–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vedel AG, Holmgaard F, Rasmussen LS et al. High-Target Versus Low-Target Blood Pressure Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass to Prevent Cerebral Injury in Cardiac Surgery Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2018;137:1770–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian DH, Wan B, Bannon PG et al. A Meta-Analysis of Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest Versus Moderate Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest with Selective Antegrade Cerebral Perfusion. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiMarco A, Velez H, SoItero E et al. Lowest Safe Hematocrit Level on Cardiopulmonary Bypass in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2011;103:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bar-Yosef S, Anders M, Mackensen GB et al. Aortic Atheroma Burden and Cognitive Dysfunction after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikram A, Mohiuddin H, Zia A et al. Does Epiaortic Ultrasound Screening Reduce Perioperative Stroke in Patients Undergoing Coronary Surgery? A Topical Review. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;50:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klamt JG, Vicente WVA, Garcia LV et al. Neuroprotective Anesthesia Regimen and Intensive Management for Pediatric Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Review and Initial Experience. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;32:523–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis C, Parulkar SD, Bebawy J et al. Cerebral Neuromonitoring During Cardiac Surgery: A Critical Appraisal with an Emphasis on near-Infrared Spectroscopy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:2313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alaeddine M, Badhwar V, Grau-Sepulveda MV et al. Aortic Clamping Strategy and Postoperative Stroke. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:1451–7 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reents W, Zacher M, Boergermann J et al. Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting and Stroke-Exploratory Analysis of the Gopcabe Trial and Methodological Considerations. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;66:464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eysenbach G Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (Cherries). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Story DA, Tait AR. Survey Research. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (Redcap)--a Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sniecinski RM, Bennett-Guerrero E, Shore-Lesserson L. Anticoagulation Management and Heparin Resistance During Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Survey of Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Members. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:e41–e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL et al. 2011 Accf/Aha Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e652–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RS, Jacobs JP, Badhwar V et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: 2018 Update on Outcomes and Quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B et al. On-Pump Versus Off-Pump Coronary-Artery Bypass Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun LY, Chung AM, Farkouh ME et al. Defining an Intraoperative Hypotension Threshold in Association with Stroke in Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hori D, Nomura Y, Ono M et al. Optimal Blood Pressure During Cardiopulmonary Bypass Defined by Cerebral Autoregulation Monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1590–8 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown CHt, Neufeld KJ, Tian J et al. Effect of Targeting Mean Arterial Pressure During Cardiopulmonary Bypass by Monitoring Cerebral Autoregulation on Postsurgical Delirium among Older Patients: A Nested Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng F, Sheinberg R, Yee MS et al. Cerebral near-Infrared Spectroscopy Monitoring and Neurologic Outcomes in Adult Cardiac Surgery Patients: A Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:663–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seco M, Edelman JJ, Van Boxtel B et al. Neurologic Injury and Protection in Adult Cardiac and Aortic Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelman R, Baker RA, Likosky DS et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American Society of Extracorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Bypass--Temperature Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:748–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldfarb M, Drudi L, Almohammadi M et al. Outcome Reporting in Cardiac Surgery Trials: Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reves JG. An Essay on 35 Years of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim C, Vasaiwala S, Haque F et al. Radiation Safety among Cardiology Fellows. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:125–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjertnaes OA, Garratt A, Botten G. Nonresponse Bias and Cost-Effectiveness in a Norwegian Survey of Family Physicians. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31:65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott A, Jeon SH, Joyce CM et al. A Randomised Trial and Economic Evaluation of the Effect of Response Mode on Response Rate, Response Bias, and Item Non-Response in a Survey of Doctors. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez Suarez FE, Fernandez Del Valle D, Gonzalez Alvarez A et al. Intraoperative Care for Aortic Surgery Using Circulatory Arrest. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:S508–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz LM Jr. et al. Stroke and Encephalopathy after Cardiac Surgery: An Update. Stroke. 2006;37:562–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.