“There must exist a paradigm, a practical model for social change that includes an understanding of ways to transform consciousness that are linked to efforts to transform structures.”

bell hooks, Killing Rage: Ending Racism1

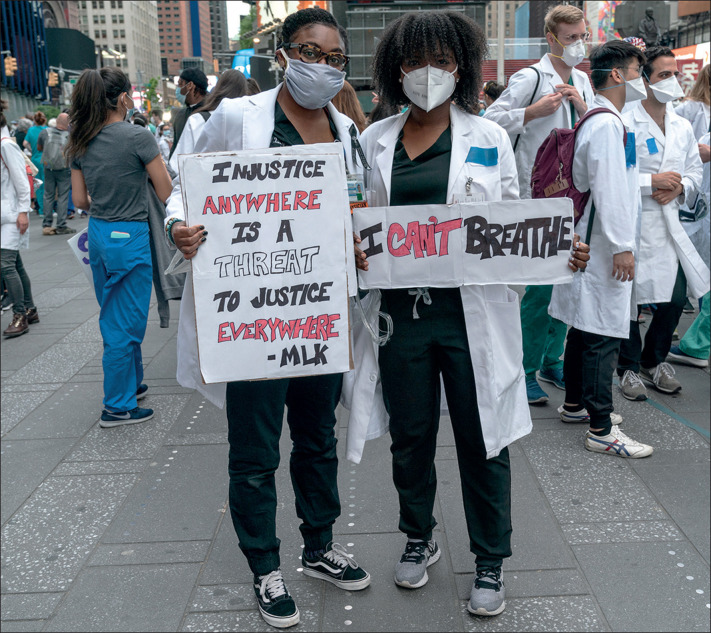

The devastating effects of police brutality, maternal mortality, and COVID-19 all have one commonality: they render disproportionate, deadly impact on marginalised and minoritised communities in the USA.2 After worldwide anti-racism protests in response to the 2020 murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, among others, several predominantly White health organisations denounced racism—specifically structural racism—and unprecedentedly declared “Black Lives Matter”. However, these declarations will require long-term commitments to equity and anti-racism, specifically anti-Black racism, within their organisations and within the health system and society at large. As Ibram X Kendi has written, “One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an anti-racist”.3 Being anti-racist necessitates that institutions challenge structural racism and other intersecting oppressive systems—eg, ableism, classism, ethnocentrism, homophobia, sexism, transphobia—by shifting power—eg, funding and other critical resources, policies, processes, leadership, culture—so that marginalised and minoritised peoples can live healthily and thrive.

Structural racism—how societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems4 including the health-care system—violates the human rights of minoritised people. And structural racism is associated with adverse health outcomes—eg, poor health-care quality and access, increased risk of preterm birth and low birthweight, increased risk of cancer—and perpetuates health inequities through mechanisms including racial segregation—ie, residential, school, workforce—immigration policy, and discriminatory incarceration.4, 5 Practical steps to incorporate an anti-racist lens are needed to remedy structural racism in medicine. For instance, the recognition of racism, not race, as a root cause or driver of health inequities and the establishment of systems that collect and disaggregate health outcome data by race and ethnicity as well as how racism may be operating (eg, discrimination, not meeting required standards of care) can be used as the basis for community-engaged quality improvement in health-care settings.6, 7 Moreover, Hardeman and colleagues2 recommend adopting universal single-payer health care, diversifying the health-care workforce, implementing medical training and competency that includes not only an awareness of racism but also how to address it, establishing performance standards related to structural racism and equity for health-care systems, and advocating for patients unjustly impacted by health inequities, even victims of police brutality.

Applying an anti-racist lens is not only a moral imperative in health care, it is also an efficient, equitable strategy. Advances in digital health are increasingly shaping clinical practice in the USA and elsewhere and will continue to do so. It is negligent to produce inequitable health outcomes, even inadvertently so, including within algorithmic-based medical innovations, such as artificial intelligence, digital health, precision medicine, wellness genomics, and other innovations that are intended to empower individuals for better health.8 Each is a double-edged instrument if not forged in anti-racism. Medical innovation offers great potential for refining clinical decision making to move towards health equity. Yet algorithmic bias in medical innovation can be deadly, as shown, for example, where biased algorithms were used to allocate patients into “high risk care management” programmes, but instead systematically discriminated against and endangered thousands of patients in the USA.9 Medical innovations produced without an anti-racist, structural justice lens are harmful. Medical innovations as equity instruments need to be designed by a meaningfully diverse cadre of engineers, social scientists, community and patient advocates, and health-care providers.10 Designers must test their algorithms in health-care settings that serve different patient populations—eg, younger, White, relatively healthier patients, and predominantly minoritised communities.11

© 2020 Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket/Getty Images

As such innovation develops and increases its reach within health care by function and intentional design, so too must anti-racism in causal algorithmic pathways to achieve equity in effect. Medical innovation must be an unbiased estimator that ever aspires toward equitable outcomes, albeit that unbiased innovation does not eviscerate bias.2 Health system data need to be collected and used with an “algorithmic scrutiny”,12 ensuring equity as a built-in process outcome in medical innovation tools. It is important that physicians who use innovations, and the designers who make them, are confident in their abilities to address legacies of structural racism within the clinical setting as it bears on health outcomes. This is arguably a non-negotiable skill and should be a tenet of 21st-century medicine.

The USA is shifting demographically, epidemiologically, and in terms of opportunities to which some are exposed and others are not. Projections are that the nation is approaching a shortage of health professionals,13 particularly among minoritised physicians,14 for whom the trajectory into medicine is often rife with barriers. Health care in the USA is becoming more expensive to manage as use of clinical services increases.15 Research shows that about 50–80% of health outcomes are determined by social, structural, and root cause factors outside of clinical settings.16 In the spirit of bell hooks, there must be a paradigm shift such that health-care providers are trained to legitimate and incorporate anti-racist models into their practice which recognise these structural determinants of health. This level of consciousness-raising must start no later than pre-medical education, continuing throughout ongoing licensure, accountability, and accreditation processes.17, 18

A priority for medical education must be building an anti-racist, structural competency skill set.2 This involves training at the interdisciplinary nexus of medicine and the disciplines that highlight how deeply entrenched social dynamics of power, opportunity, and wellness are delineated along racial lines. Anti-racist, structural competency training needs to start from pre-medicine pathways and will be essential for reimagining justice in the medical workforce pipeline. Undergraduate students who are trained in anti-racist, structural competency have increased capacities for understanding root structural causes of disease.18 It is not enough for burgeoning clinicians to know the body, inside and out. They must also know the historical body of work about enduring medical practices based on exploitation and/or exclusion and long-standing medical policies that render certain populations sicker than others; such knowledge informs their structural competency skills development. For the same reason, new and established physicians must undergo consistent, continuing medical education that includes anti-racist, structural competency training. Such level training makes for better doctors who are well prepared to address the needs of a changing nation and a changing world.19 This is what medical education justice in practice should look like.

An anti-racist, structural justice approach is the crucial narrative frame that health-care practitioners need so that they can dismantle, reimagine, and redesign health care in a changing society. Unequivocally, health is a right and anti-racism is its right-bearer.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. The views expressed in this Comment are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policy of the American Medical Association.

References

- 1.Hooks B. Henry Holt and Company; New York, NY: 1996. Killing rage: ending racism. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Boyd RW. Stolen breaths. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021072. published online June 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendi IX. Random House; New York, NY: 2019. How to be an antiracist. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequalities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crear-Perry J. Race isn't a risk factor in maternal health. Racism is. Rewire News. April 11, 2018 https://rewire.news/article/2018/04/11/maternal-health-replace-race-with-racism/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore M. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. July 2, 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juengst ET, McGowan ML. Why does the shift from “personalized medicine” to “precision health” and “wellness genomics” matter? AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:e881–e890. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2018.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366:447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjamin R. Polity Press; Medford, MA: 2019. Race after technology: abolitionist tools for the new Jim Code. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheny M, Israni ST, Ahmed Whicher D, editors. Artificial intelligence in health care: the hope, the hype, the promise, the peril. NAM Special Publication. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen IY, Szolovits P, Ghassemi M. Can AI help reduce disparities in general medicine and mental health care? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21:e167–e179. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2019.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges New findings confirm predictions on physician shortage. April 23, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/new-findings-confirm-predictions-physician-shortage#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20will%20see,Association%20of%20American%20Medical%20Colleges

- 14.Gantz S. Physicians of color are far too rare: study highlights one potential reason. Medical Xpress. Sept 25, 2019 https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-09-physicians-rare-highlights-potential.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services National health expenditures 2017 highlights. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf

- 16.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prevent Med. 2016;50:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting Black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2113–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petty J, Metzl JM, Keeys MR. Developing and evaluating an innovative structural competency curriculum for pre-health students. J Med Humanit. 2017;38:459–471. doi: 10.1007/s10912-017-9449-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metzl JM, Maybank A, De Maio F. Responding to the COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9289. published online June 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]