Abstract

We present an extracellular matrix (ECM)-based gradient generator that provides a culture surface with continuous chemical concentration gradients created by interstitial flow. The gelatin-based microchannels harboring gradient generators and in-channel micromixers were rapidly fabricated by sacrificial molding of a 3D-printed water-soluble sacrificial mold. When fluorescent dye solutions were introduced into the channel, the micromixers enhanced mixing of two solutions joined at the junction. Moreover, the concentration gradients generated in the channel diffused to the culture surface of the device through the interstitial space facilitated by the porous nature of the ECM. To check the functionality of the gradient generator for investigating cellular responses to chemical factors, we demonstrated that human umbilical vein endothelial cells cultured on the surface shrunk in response to the concentration gradient of histamine generated by interstitial flow from the microchannel. We believe that our device could be useful for the basic biological study of the cellular response to chemical stimuli and for the in vitro platform in drug testing.

I. INTRODUCTION

Cellular behaviors, such as migration, differentiation, and organization, are largely influenced by their surrounding microenvironments including concentration of soluble chemical factors, mechanical stimuli, and the composition of extracellular matrix (ECM) in vivo.1–4 These constituents in the microenvironments intricately and harmoniously act on cells in our body to maintain tissue homeostasis.5,6 In particular, major elements in the microenvironments such as soluble chemical factors diffuse to the cells in tissues from separated paracrine systems or body fluid through interstitial flow.7,8 Interstitial flow describes fluid flow through the ECM around interstitial cells in all tissues.9,10 Although interstitial flow plays an important role in determining the spatial distribution of chemical factors to control the behaviors of cells, the precise responses and mechanisms of those cellular behaviors to interstitial-flow-based chemical stimuli remain unclear. To understand the behavior, in vitro analytical platforms that can observe the cellular response to interstitial-flow-based chemical stimuli are necessary.

Microfluidic-based in vitro devices have been the current gold standard to investigate cellular behaviors in response to chemical factors with in-channel concentration gradient.11–14 The advantages conferred by gradient generators included generating a microscale gradient at single-cell resolution and spatial and temporal controllability of concentration gradients for long-term culture.15–17 A tree-shaped network is the most common design of microfluidic-based gradient generators.18–20 However, with these traditional tree-shaped network devices, cells cultured within the surface of microchannels are exposed to the chemical factors directly from the fluid flow in the channel.21,22 Furthermore, the cells were affected not only by chemical factors but also by fluid shear stress. Although in vitro simple interstitial chemical gradient was demonstrated by using a microfluidic tissue culture system,23 a gradient generator allowing to investigate the cellular responses to the controlled and complex concentration gradient of chemical factors generated through interstitial flow has not been established to date.

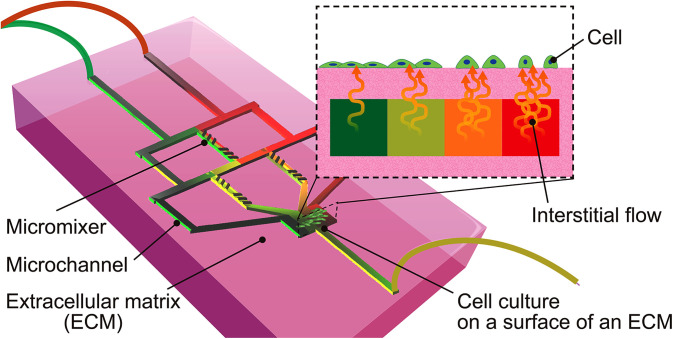

Here, we propose an ECM-based gradient generator made of transglutaminase enzymatically cross-linked gelatin (TG gelatin) that allows tuning the surface chemical environment created by the interstitial flow (Fig. 1). Our device can generate a culture surface with a controlled concentration gradient of chemical factors on the surface of the ECM by the interstitial flow. The concentration gradient formed in the channel diffused through TG gelatin due to its porous nature, translating to the outer surface of the device. The tree-shaped microchannel with in-channel micromixers in the ECM can be monolithically constructed using a 3D-printed water-soluble sacrificial mold made with a composite of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Thereafter, cellular response to chemical factors with various concentrations driven by the interstitial flow can be observed at once with the device. To illustrate the proof-of-concept, we investigated the response of endothelial cells to histamine stimuli through interstitial flow created in our device.

FIG. 1.

Concept of an ECM-based gradient generator. This device can generate a culture surface with a controlled chemical factor concentration gradient by the interstitial flow. Cellular response to chemical factors by an interstitial flow can be observed exhaustively with this device.

II. EXPERIMENTAL

A. Chemicals

For the fabrication of the ECM-based microchannel, gelatin from porcine skin powder (gel strength ∼300 g Bloom, Type A) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan), transglutaminase (Moo Gloo TI) from Modernist Pantry (ME, USA), phosphate buffered saline (–) 10× (PBS) from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan), and de-ionized water from a Millipore purification system.

For concentration gradient generation, fluorescein was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan), Rhodamine B from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

For cell culture, green fluorescent protein-expressing human umbilical vein endothelial cells (GFP-HUVECs) were obtained from Angio-Proteomie (Boston, MA, USA), Endothelial Cell Growth Medium-2 BulletKit (EGM-2) from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland), Trypsin-EDTA from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), and histamine from Sigma-Aldrich (Tokyo, Japan).

B. Fabrication of gelatin-based gradient generator by sacrificial molding

Gelatin powder was dissolved in 10× PBS (–) at 45 °C to prepare a 15% (w/v) gelatin pre-gel solution. The gelatin pre-gel solution was stored at 4 °C until use. Transglutaminase enzyme (TG) was dissolved in PBS as a 5% (w/v) enzyme solution and set aside for use to cross-link gelatin. In order to produce TG gelatin, the enzyme solution was added to the gelatin pre-gel solution at a volume ratio of 1:5 at 45 °C, with constant stirring, to prepare a 12.5% (w/v) TG gelatin solution.

The TG gelatin-based gradient generator was fabricated by the sacrificial molding of a water-soluble sacrificial mold printed using a fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer.24–26 First, the design of the sacrificial mold was drawn by AutoCAD (Autodesk, Inc., CA, USA). The designed mold was printed in a layer-by-layer assembly by a FDM 3D printer (ROKIT, Seoul, South Korea) with a filament made with a composite of PVA. Thereafter, the printed PVA mold was detached from the printing bed and stored in an air-tight container until ready to use. In order to extrude the filament, we programmed the preset temperature of the extruder to 190 °C, and the diameter of the nozzle installed was 200 μm.

The TG gelatin-based microchannel consisted of three components, namely, (1) a bottom layer, (2) an embedded sacrificial mold, and (3) a top layer of gelatin. The solution of TG gelatin (prior to gelation) was dispensed into a Petri dish and cooled on ice to cure to form the bottom layer of TG gelatin (∼0.7 mm in thickness). Thereafter, the PVA mold was placed onto the cured bottom layer. An additional solution of TG gelatin was dispensed and then cured on ice as a top layer (∼2.8 mm in thickness) to embed the PVA mold in TG gelatin completely. The enzyme in TG gelatin was activated in a drying oven (MOV-112F-PJ, SANYO) at 28–32 °C for 2 h. Thereafter, the cured TG gelatin was cut to expose both ends of the PVA mold, and, then, the device was dipped into hot water to remove the PVA mold by dissolution. The microchannel-embedded gel was stored in a sterile Petri dish at 4 °C overnight until further use.

C. Generation of a fluorescent dye concentration gradient in the device

We investigated the formation of the concentration gradient and the diffusion of the chemical factor in the device. The green fluorescent solution was prepared by dissolving fluorescein (0.1 mM) in DMSO and PBS, and the red fluorescent solution was prepared by dissolving Rhodamine B (0.04 mM) in DMSO and PBS. Both solutions containing the green and red fluorescent dyes were injected into the TG gelatin-based microchannels connected to silicone tubes by using a syringe pump (KD Scientific) at 83 μl/min for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The fluorescent dyes in the device were visualized under an inverted fluorescence/phase-contrast microscope (IX73PI-22FL/PH, Olympus). The microchannels were designed with and without the patterns of micromixers. The fluorescent images showing the quadruple channels of the devices were obtained under the fluorescent microscope to confirm the effect of the micromixer patterns. After flow the solutions, the devices were cut by using a knife to observe the cross-sectional views of the culture area of the devices by putting the cross-sectional plane on the imaging plane directly. The fluorescent images showing the cross-sectional views of the culture area of the devices were obtained under the fluorescent microscope to check the diffusion of the fluorescent dyes through the interstitial space. The intensity of the obtained fluorescent images was analyzed by Image J [National Institutes of Health (NIH)].

D. Cellular response to chemical factors driven by an interstitial flow

Cellular response to the chemical concentration gradient was studied using GFP-HUVECs and histamine. Before seeding cells on the device, GFP-HUVECs were incubated in the medium on cell culture dishes in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to 80% confluence. HUVECs from passage numbers 6–9 were dissociated from the dishes with 0.125% trypsin-EDTA. The solution mixing the trypsinized cells and the fresh medium was centrifuged at 500× g at 22 °C for 5 min to obtain the cell pellet. The cell pellet was suspended in the medium at a density of as a GFP-HUVEC suspension for use.

The TG gelatin-based microchannel was autoclaved in DI water in a cycle of 20 min at 120 °C for sterilization. Thereafter, the autoclaved device was steeped in a medium for 2 h. After removing the medium, the gel was incubated and dried to evaporate excess water of the surface at room temperature for 2 h. The GFP-HUVEC suspension was poured on the culture area of the device and then incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 2 h for cells to adhere to the surface of the device. Two hours after cell seeding, the medium was added to the device and then the device was incubated for 4 days.

A histamine solution was prepared by mixing histamine (2 mg/ml) in the medium. Both media with and without histamine were injected to the device embedding the patterns of micromixers connected silicone tubes by using the syringe pump at 83 μl/min for 2 h under the fluorescent microscope 3–4 days after culturing. The GFP-HUVECs cultured on the surface of the device were visualized under the fluorescence microscope.

E. Image processing

To evaluate the area of GFP-HUVECs cultured on the surface of the device before and 2 h after introducing the media with and without histamine, the fluorescent images were obtained under the fluorescent microscope. The fluorescent images of the HUVECs were cropped with 227 × 227 pixels. The contrast and brightness of the cropped images were algorithmically adjusted and then the images were converted to 32-bit gray scale images by Image J. Thereafter, the processed images were binarized and then the area of HUVECs was measured.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Sacrificial molding to fabricate ECM-based concentration gradient generator

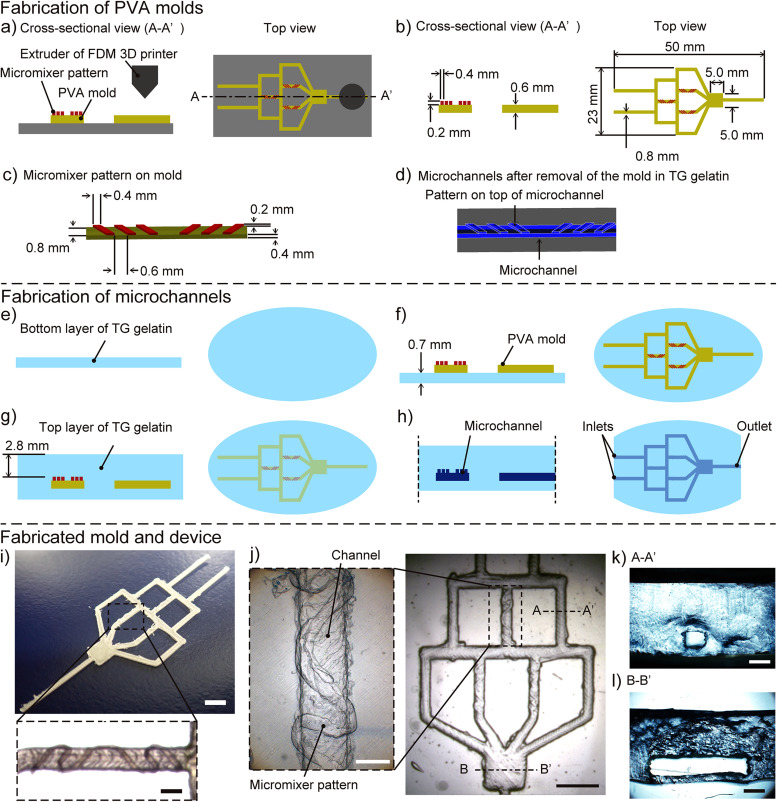

The gradient generator with in-channel micromixers was fabricated by the sacrificial molding of a 3D-printed mold made of a composite of PVA (Fig. 2). By selecting water-soluble PVA as the primary material of the sacrificial mold, the removal of the mold was carried out in the water. In addition, the use of FDM 3D printing enabled direct patterning of micromixers onto the sacrificial mold. The thickness of the micromixer patterns was ∼200 μm, referring to the previously reported design.27 We demonstrated the facile fabrication of the microchannel in TG gelatin by following two major steps. The first step of the fabrication was the FDM 3D printing of sacrificial molds [Fig. 2(a)]. The sacrificial mold was printed according to the CAD design input into the 3D printer [Fig. 2(b)]. The micromixer pattern included six grooves that were placed in two sets of three grooves orientated in asymmetrical directions [Fig. 2(c)]. Based on the sacrificial mold, the design of the micromixer pattern was imparted onto the top surface of the microchannel in the TG gelatin matrix [Fig. 2(d)]. The second step was the fabrication of the microchannels in TG gelatin by sacrificial molding. A thin slab of TG gelatin was prepared and allowed to cure to form the bottom layer [Fig. 2(e)]. The sacrificial mold was placed on the surface of the bottom layer and embedded by adding a top layer of TG gelatin [Figs. 2(f) and 2(g)]. The design of the in-channel micromixers on the microchannel of the sacrificial mold was replicated onto the TG gelatin after the matrix has cured [Fig. 2(h)]. After the TG gelatin was fully cured, the terminal points of the mold containing the inlets and the outlets were cut to expose the sacrificial mold to a hot water by dissolution.

FIG. 2.

Fabrication of the TG gelatin-based microchannel by using 3D-printed PVA sacrificial molds. (a) A sacrificial PVA mold is printed by an FDM 3D printer. (b) The printed mold was detached from a printing bed. (c) Design of micromixer patterns on 3D-printed PVA sacrificial mold. (d) Design of microchannels imparted onto TG gelatin after the mold was removed, showing micromixer patterns on top surface of microchannel. (e) A bottom layer of TG gelatin in a Petri dish was solidified on ice. (f) The sacrificial mold was put on the bottom layer of TG gelatin. (g) A top layer of TG gelatin was poured over the mold and cured on ice to embed the mold into the TG gelatin. (h) The cured TG gelatin was cut at both ends of the PVA mold. Thereafter, hot water was flushed to dissolve and remove the mold. (i) The whole view of the printed PVA mold (scale bar = 5 mm). The inset shows an in-channel micromixer pattern (scale bar = 1 mm). (j) The whole view of the TG gelatin-based channel (scale bar = 5 mm). The inset shows a surface pattern of the TG gelatin-based channel serving as a micromixer (scale bar = 1 mm). (k) The A–A′ cross-sectional view of the fabricated device (scale bar = 1 mm). The square channel was constructed in TG gelatin. (l) The B–B′ cross-sectional view of the fabricated device (scale bar = 1 mm). The culture area was constructed in TG gelatin.

Our current study required to control the generation of interstitial flow from the microchannel into the tissue space, and we postulated that the efficient generation of a spatial gradient could be facilitated by including in-channel features that enhanced mixing.24 The in-channel micromixers patterned on the sacrificial mold was faithfully 3D-printed with PVA composites [Fig. 2(i)], and the patterns were imparted onto the microchannel embedded in TG gelatin after the sacrificial mold was removed in water [Fig. 2(j)]. The resultant microchannel was used to enhance the propensity of mixing in the gradient generator fabricated in TG gelatin, which is discussed in Sec. III B. The cross-sectional views showed the rectangular channel in TG gelatin [Figs. 2(k) and 2(l)].

B. The effect of micromixer patterns

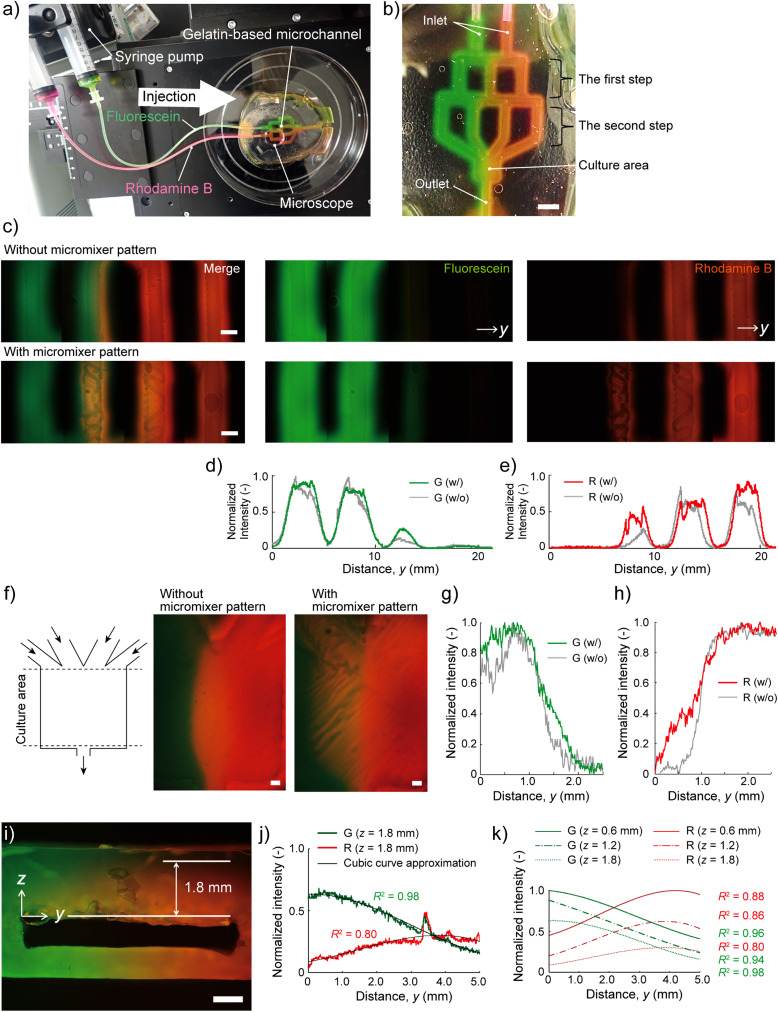

To study the effect of the micromixer of the gradient generator, we infused green and red fluorescent dye solutions in the device with/without micromixer patterns for 30 min [Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)]. Two inflows diverged from the two inlets to the three branched parallel channels (the first step) and then the three divided flows diverged again from the first step to the four branched parallel channels (the second step) [Fig. 3(c)]. In the device without the micromixers [Fig. 3(c), top images], the boundary between the green and red colors at the second step was distinct. Without the micromixer, the merged flow was not entirely mixed due to the laminar flow and then separated to each green and red colored flow again at the middle channel in the first step. On the other hand, with the micromixers [Fig. 3(c), bottom images], a yellow-colored fluorescent flow was observed at the second step [Fig. 3(c), bottom left image]. The yellow color suggested that the two merged flows (i.e., red and green) were mixed and then divided into two flows equally at the middle channel in the first step. Finally, four flows divided at the second step were joined at the culture area to form the concentration gradient.

FIG. 3.

Diffusion of molecular fluorescent dyes with the TG gelatin-based gradient generator. (a) Fluorescein (100 mM) and Rhodamine B (40 mM) were injected to the device by using a syringe pump at 5 ml/h. (b) The optical image showing the device 30 min after perfusion (scale bar = 5 mm). (c) The fluorescent images showing the devices without micromixer patterns (top) and with micromixer patterns (bottom) in the second step region at 30 min after perfusion of fluorescein (green) and Rhodamine B (red) (scale bars = 1 mm). (d) and (e) Normalized fluorescent intensity profiles of the fluorescein [green, (d)] and Rhodamine B [red, (e)] in the second step regions at 30 min after perfusion. Both fluorescent signals were normalized by the highest fluorescent intensities in the images, referring to the fluorescein (100 mM) and Rhodamine B (40 mM), respectively. (f) The fluorescent images in the culture area of the devices without (left) and with (right) micromixer patterns at 30 min after perfusion (scale bars = 0.5 mm). (g) and (h) Normalized fluorescent intensity profiles of the fluorescein [green, (g)] and Rhodamine B [red, (h)] in the culture at 30 min after perfusion. (i) The fluorescent image showing the cross-sectional view of the culture area of the device, 30 min after perfusion (scale bar = 1 mm). (j) Normalized fluorescent intensity in the interstitial space at z = 1.8 mm from the channel. Both signals were fit to cubic curve approximation. (k) Normalized fluorescent intensities of cubic curve approximations at 0.6, 1.2, and 1.8 mm show the diffusion of the fluorescein and Rhodamine B in the interstitial space from the channel to the culture surface.

To quantify the effect of the micromixers, we analyzed the intensity of the fluorescent images at the second step. The green intensity at the third channel form the left with the micromixers was higher than that without the micromixers [Fig. 3(d)]. Similarly, the red intensity at the second channel from the left with the micromixers was higher than that without the micromixers [Fig. 3(e)]. As a result, on the culture area [Fig. 3(f)], the fluorescent intensity profiles show that concentration gradient was clearer in the device with micromixer pattern than that without the micromixer pattern [Figs. 3(g) and 3(h)]. These results indicate that two colored fluorescent inflows were repeatedly divided and joined to four colored fluorescent flows downstream, and the micromixer patterns enhanced the mixing of the joined green and red solutions. Using this result, the chemical concentration of the created gradient can roughly be estimated by assuming that the highest normalized fluorescent intensity represents the original concentration of the induced chemicals, that is, 100 mM for the Fluorescein and 40 mM for the Rhodamine B, respectively.

C. The concentration gradient in the interstitial space

We checked the diffusion of the fluorescent dyes in the interstitial space from the channel to the culture surface (i.e., outer surface of the TG gelatin device) 30 min after introducing fluorescent solutions [Fig. 3(i)]. The concentration gradient of green and red fluorescent dyes was observed in the TG gelatin above and below the channel. The fluorescent intensity profile [Fig. 3(j)] shows that the green intensity in the horizontal position (z = 1.8 mm) was gradually decreased as the y-coordinate was increased. Besides, the red intensity was gradually increased. Thereby, the concentration gradient was generated to the horizontal direction not only in the channel but also in the interstitial space. The range of the coefficient of determination, R2, of the cubic curve approximations of the green and red intensities was 0.80–0.98. Moreover, the cubic curve approximations showing both the green and red intensities at each depth (z = 0.6 mm, 1.2 mm, and 1.8 mm) were gradually decreased as the z-coordinate was increased [Fig. 3(k)]. The intensity data suggested that the fluorescent dyes diffused from the channel to the surface of the device. These results indicated that the chemical factors reached the culture surface of the device from the channel by the interstitial flow. The concentration gradient at the outer surface of the device reflected that in the channel, which was diffused through the ECM by the interstitial flow.

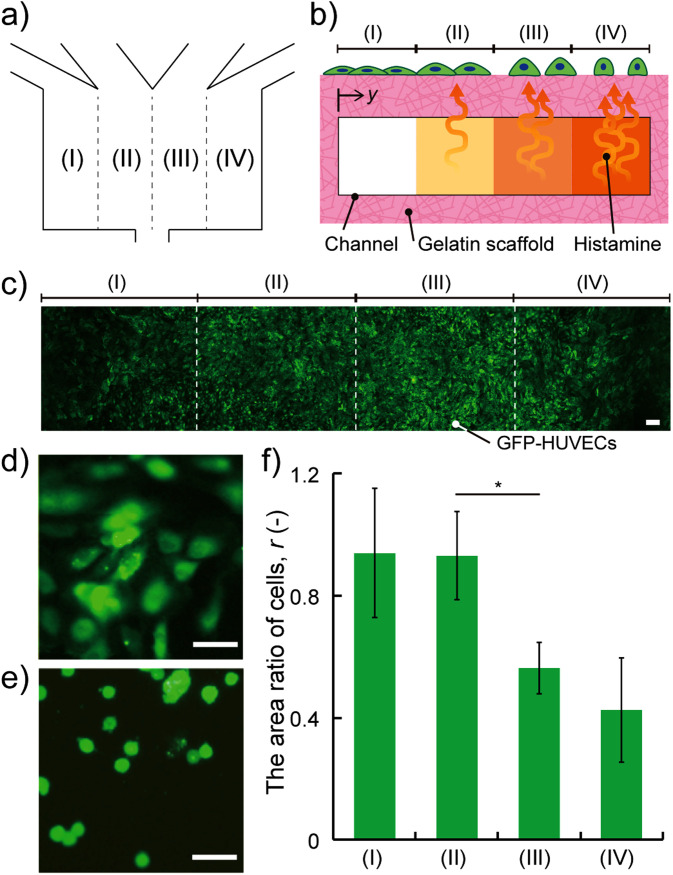

D. The cellular response to chemical factors with the concentration gradient

To evaluate the functionality of our device, we examined the responses of endothelial cells when exposed to histamine to elicit an allergy reaction in vivo.28–30 Endothelial cells are known to be contracted by histamine in immune responses to increase the permeability to transport immune cells to inflammatory regions. The activation of Rho small GTP binding protein (Rho GTPase) by histamine is the trigger of the reaction. Activated Rho GTPase stimulates the polymerization of the actin and generation of the actin stress fiber through forming homology protein and Rho kinase, causing the decrease of cell sizes.31–34 To demonstrate the HUVEC response to histamine with the concentration gradient driven by the interstitial flow, we introduced both media with and without histamine into the device culturing GFP-HUVECs (shown in video in the supplementary material). To evaluate the propensity of shrinkage of HUVECs, we calculated the area ratio comparing the area of cells before and 2 h after introducing histamine, r (–), at area (I) (y = 0–1.25 mm), (II) (y = 1.25–2.5 mm), (III) (y = 2.5–3.75 mm), and (IV) (y = 3.75–5.0 mm) [Figs. 4(a)–4(c)] as follows:

| (1) |

where Aafter (μm2) is the area of HUVECs after introducing histamine and Abefore (μm2) is the area of HUVECs before introducing histamine, measured with the fluorescent images. HUVECs cultured on the surface of the high histamine flow greatly contracted compared to the flow without histamine [Figs. 4(d) and 4(e)]. Moreover, the difference of the area ratio of cells, r, at area (II) [0.93 ± 0.14 (mean ± SD), n = 6] and at area (III) (0.56 ± 0.17, n = 6) was clear (p < 0.01 by Student's t-test) [Fig. 4(f)]. The larger the y position (closer to the high histamine region) was, the lower the area ratio, r, was. These results indicate that HUVECs cultured on the surface of the device responded to histamine with the concentration gradient driven by the interstitial flow.

FIG. 4.

HUVECs cultured on the surface of the device respond to histamine with a concentration gradient driven by the interstitial flow. (a) Schematic of four areas in the culture area. (b) Cross-sectional view of the four areas: (I) (y = 0–1.25 mm), (II) (y = 1.25–2.5 mm), (III) (y = 2.5–3.75 mm), and (IV) (y = 3.75–5.0 mm). (c) Fluorescent image of GFP-HUVECs cultured on the area. (d) and (e) GFP-HUVECs (green) at the area (IV) shrunk before and after introducing medium with histamine at 2 h (scale bars = 50 μm). (f) The area ratio of cells at (I)–(IV) after histamine exposure. The data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.01 by Student's t-test (n = 6).

E. Discussion

The current results demonstrated that our device enabled us to assay the cellular response to chemical factors with the concentration gradient generated by the gradient generator on the outer surface of the microfluidic devices. Previous papers have reported biomicrofluidic devices that could directly apply chemical factors with concentration gradient to cells cultured inside the channel.21,22 In particular, the tree-shaped gradient generation method has some advantages such as easy design, easy calculation, and reduced inflows.20,35 Moreover, the gradient shape can be controlled by the design of the microchannel with the tree-shaped gradient method.16,19 However, the demonstration has been limited to create chemical environments inside the channels. Methods to expose a controlled concentration gradient to cells through the ECM by interstitial flow have not been established. By fabricating the tree-shaped microchannel composed of TG gelatin, the chemical factor with the concentration gradient generated in the channel could reach to the culture surface thanks to the porous structure of gelatin. Thereby, the culture surface with chemical factors with concentration gradient driven by the interstitial flow was successfully generated by infusing only two types of fluids: chemical-factor-dissolving solution and buffer solution. To quantify the concentration of the diffused chemicals in the microchannel or on the surface of the culture area, confocal fluorescent microscopy would provide the information on an exact fluorescent intensity at the sliced plane. Another important feature of our gelatin-based gradient generator is that chemicals in the microchannel gradually diffuse out to the surrounding culture medium via gelatin matrix, causing the saturation of the chemical gradient especially for long-time experiment (more than several hours). To maintain the created chemical gradient, frequent or continuous medium change would be necessary to keep the concentration of the chemicals in the culture medium outside of the device nearly zero.

In contrast, our study observed the response of HUVECs cultured on the surface of the gelatin to histamine driven by the interstitial flow. Blood vessels covered with endothelial cells are affected by histamine in the allergen reaction.36 After the response to histamine, endothelial cells shrink, and the barrier function of endothelial cells is broken.37 Finally, the occurred vascular leakage caused the inflammation.38,39 By multi-layering the gelatin-based microchannel to construct vessel-like microchannels above our gradient generator, the platform that mimics the leakage of the blood plasma by histamine exposure could be established. In addition, by combining our system and a mechanical-stimulus platform25 that can apply compositive mechanical stimuli to cells, an in vitro vascular model that can control both chemical and mechanical stimuli could be constructed. The combined vascular model could imitate an in vivo microenvironment that vascular endothelial cells were exposed not only with chemical stimuli but also with mechanical stimuli such as stretch stress and fluid shear stress caused by blood flow.40 With these improvements, our device could be useful for the fundamental biological study of the cellular response to external stimuli and for the in vitro platform in drug testing.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

We proposed an ECM-based gradient generator that provided a culture surface with a chemical concentration gradient created by interstitial flow from the microchannel beneath. The gelatin-based microfluidic device with in-channel micromixers was fabricated using the 3D-printed PVA mold. We confirmed that the device, patterned with tree-shaped networks with micromixers, generated concentration gradients of fluorescent dye solutions. In addition, the controlled concentration gradient was diffused from the channel to the culture surface by the interstitial flow. HUVECs cultured on the surface of the device responded to the histamine with the controlled concentration gradient provided by the interstitial flow. We believe that our device could be a useful tool for the fundamental studies of the cellular response to external stimuli.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the video in the supplementary material for the response of the GFP-HUVECs cultured on the gradient generator.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A.S. and W.H.G. contributed equally to this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 19H04440) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Japan, and the research grant from Digital Manufacturing and Design Centre (DManD) at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) (No. RGDM1620403), Singapore.

Contributor Information

Michinao Hashimoto, Email: .

Hiroaki Onoe, Email: .

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang F., Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 1, a002980 (2009). 10.1101/cshperspect.a002980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies P. F., Physiol. Rev. 75, 519–560 (1995). 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sieminski A. L., Hebbel R. P., and Gooch K. J., Exp. Cell Res. 297, 574–584 (2004). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutolf M. P. and Hubbell J. A., Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 47–55 (2005). 10.1038/nbt1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattazzo F., Urciuolo A., and Bonaldo P., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1840, 2506–2519 (2014). 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quail D. F. and Joyce J. A., Nat. Med. 19, 1423–1437 (2013). 10.1038/nm.3394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan T. M. and Folch A., Lab Chip 8, 34–57 (2007). 10.1039/B711887B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helm C. L. E., Fleury M. E., Zisch A. H., Boschetti F., and Swartz M. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15779–15784 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0503681102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutkowski J. M. and Swartz M. A., Trends Cell Biol. 17, 44–50 (2007). 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swartz M. A. and Fleury M. E., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 9, 229–256 (2007). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X., Liu Z., and Pang Y., RSC Adv. 7, 29966–29984 (2017). 10.1039/C7RA04494A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irimia D., Geba D. A., and Toner M., Anal. Chem. 78, 3472–3477 (2006). 10.1021/ac0518710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atencia J., Morrow J., and Locascio L. E., Lab Chip 9, 2707–2714 (2009). 10.1039/b902113b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng J. Y., Yen M. H., Te Kuo C., and Young T. H., Biomicrofluidics 2, 1–12 (2008). 10.1063/1.2952290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung B. G., Lin F., and Jeon N. L., Lab Chip 6, 764–768 (2006). 10.1039/b512667c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S., Kim H. J., and Jeon N. L., Integr. Biol. 2, 584–603 (2010). 10.1039/c0ib00055h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung B. G. and Choo J., Electrophoresis 31, 3014–3027 (2010). 10.1002/elps.201000137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englert D. L., Manson M. D., and Jayaraman A., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 4557–4564 (2009). 10.1128/AEM.02952-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dertinger S. K. W., Chiu D. T., Jeon N. L., and Whitesides G. M., Anal. Chem. 73, 1240–1246 (2001). 10.1021/ac001132d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon N. L., Dertinger S. K. W., Chiu D. T., Choi I. S., Stroock A. D., and Whitesides G. M., Langmuir 16, 8311–8316 (2000). 10.1021/la000600b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S. J., Saadi W., Lin F., Minh-Canh Nguyen C., and Li Jeon N., Exp. Cell Res. 300, 180–189 (2004). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunawan R. C., Silvestre J., Gaskins H. R., Kenis P. J. A., and Leckband D. E., Langmuir 22, 4250–4258 (2006). 10.1021/la0531493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polacheck W. J., Charest J. L., and Kamm R. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11115–11120 (2011). 10.1073/pnas.1103581108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goh W. H. and Hashimoto M., Macromol. Mater. Eng. 303, 1700484 (2018). 10.1002/mame.201700484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimizu A., Goh W. H., Itai S., Hashimoto M., Miura S., and Onoe H., Lab Chip 20, 1917–1927 (2020). 10.1039/D0LC00254B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goh W. H. and Hashimoto M., Micromachines 9(10), 523 (2018). 10.3390/mi9100523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stroock A. D., Dertinger S. K. W., Adjari A., Stone H. A., and Whitesides G. M., Science 295, 647–650 (2002). 10.1126/science.1066238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurmond R. L., Gelfand E. W., and Dunford P. J., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 7, 41–53 (2008). 10.1038/nrd2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachert C., Allergy 57, 287–296 (2002). 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1r3542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Benedetto A., Yoshida T., Fridy S., Park J.-E., Kuo I.-H., and Beck L., J. Clin. Med. 4, 741–755 (2015). 10.3390/jcm4040741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majno G., Shea S. M., and Leventhal M., J. Cell Biol. 42, 647–672 (1969). 10.1083/jcb.42.3.647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millán J., Cain R. J., Reglero-Real N., Bigarella C., Marcos-Ramiro B., Fernández-Martín L., Correas I., and Ridley A. J., BMC Biol. 8, 11 (2010). 10.1186/1741-7007-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duluc L. and Wojciak-Stothard B., Cell Tissue Res. 355, 675–685 (2014). 10.1007/s00441-014-1805-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huveneers S., Oldenburg J., Spanjoard E., van der Krogt G., Grigoriev I., Akhmanova A., Rehmann H., and de Rooji J., J. Cell Biol. 196, 641–652 (2012). 10.1083/jcb.201108120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdulla Yusuf H., Baldock S. J., Barber R. W., Fielden P. R., Goddard N. J., and Treves Brown B. J., Microelectron. Eng. 85, 1265–1268 (2008). 10.1016/j.mee.2007.12.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van De Voorde J. and Leusen I., Eur. J. Pharmacol. 87, 113–120 (1983). 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashina K., Tsubosaka Y., Nakamura T., Omori K., Kobayashi K., Hori M., Ozaki H., and Murata T., PLoS One 10, 1–16 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0132367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Lorenzo A., Fernández-Hernando C., Cirino G., and Sessa W. C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14552–14557 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0904073106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikelis C. M., Simaan M., Ando K., Fukuhara S., Sakurai A., Amornphimoltham P., Masedunskas A., Weigert R., Chavakis T., Adams R. H., Offermanns S., Mochizuki N., Zheng Y., and Gutkind J. S., Nat. Commun. 6, 6725 (2015). 10.1038/ncomms7725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao S., Suciu A., Ziegler T., Moore J. E., Bürki E., Meister J. J., and Brunner H. R., Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 1781–1786 (1995). 10.1161/01.ATV.15.10.1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the video in the supplementary material for the response of the GFP-HUVECs cultured on the gradient generator.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.