Abstract

Background

Status migrainosus is a condition with limited epidemiological knowledge, and no evidence-based treatment guideline or rational-driven assessment of successful treatment outcome. To fill this gap, we performed a prospective observational study in which we documented effectiveness of treatment approaches commonly used in a tertiary headache clinic.

Material and methods

Patients with episodic and chronic migraine who experienced continuous and prolonged attacks for more than 72 hours were treated with dexamethasone (4 mg orally twice daily for 3 days), ketorolac (60 mg intramuscularly), bilateral nerve blocks (1–2% lidocaine, 0.1–0.2 ml for both supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, 1 ml for both auriculotemporal nerves, and 1 ml for both greater occipital nerves), or naratriptan (2.5 mg twice daily for 5 days). Hourly (for the first 24 hours) and daily (for first 30 days) change in headache intensity was documented using appropriate headache diaries.

Results

Fifty-four patients provided eligible data for 60 treatment attempts. The success rate of rendering patients pain free within 24 hours and maintaining the pain-free status for 48 hours was 4/13 (31%) for dexamethasone, 7/29 (24%) for nerve blocks, 1/9 (11%) for ketorolac and 1/9 (11%) for naratriptan. These success rates depended on time to remission, as the longer we allowed the treatments to begin to work and patients to become pain free (i.e. 2, 12, 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours), the more likely patients were to achieve and maintain a pain-free status for at least 48 hours.

Discussion

These findings suggest that current treatment approaches to terminating status migrainosus are not satisfactory and call attention to the need to develop a more scientific approach to define a treatment response for status migrainosus.

Keywords: Migraine, headache, trigeminal, pain, CGRP, triptans

Introduction

Migraine is a neurological disorder characterized by intense, often throbbing and unilateral headaches that are accompanied by nausea and vomiting or increased sensitivity to light and sound (1). By definition, attacks of migraine last from 4–72 hours when untreated or unsuccessfully treated. Some patients, however, experience migraine attacks that continue for more than 3 days, and despite treatment attempts with recommended medications at home, their headache continues to be debilitating and unremitting. This phenomenon is known as status migrainosus and is classified as a complication of migraine in the current International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) (1). The current knowledge on the epidemiology of status migrainosus in limited. One retrospective study in a French tertiary headache center found that 28 out of 8821 patients with migraine experienced status migrainosus during an 11-year period (2). Aside from this study, not much is known about the occurrence of status migrainosus. The state of evidence-based management of status migrainosus is just as limited: Patients currently seeking help for attacks of migraine lasting longer than 72 hours, and unresponsive to the patient’s typical abortive medications, are commonly advised to return to the headache clinic to receive intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of medications that are not readily suitable for home treatment (3–5). The recommendation for administering treatments such as nerve blocks, steroids, and parenteral COX1/COX2 inhibitors stems from experience with treating headaches of moderate to severe pain intensity. However, as has been noticed in a recent systematic review on this topic, no randomized trials have been performed in patients with treatment-resistant attacks of migraine lasting more than 72 hours (3), and there is no international consensus guideline for the treatment of status migrainosus. In the absence of a guideline, physicians are rendered unable to evaluate their treatment success and patients don’t usually know what to expect. Consequently, fundamental questions await answers for the treatment of status migrainosus. These include: (a) Which treatment to use for each individual patient; (b) how long does it take for a given treatment to begin reducing the headache intensity; (c) how long does it take for the patient to become headache free; (d) how long does the treatment keep the patient headache free; (e) do different treatment approaches differ in the time they take to begin “working” and the duration of their effectiveness; (f) how fast should a headache resolve and how long should the remission last before a treatment is considered successful; and (g) at what point is a headache remission considered spontaneous, rather than treatment-driven. To better characterize these issues, we performed a prospective observational study on patients treated for status migrainosus in our tertiary headache center using hourly and daily headache diaries as the main outcome measure tools. Specifically, we evaluated how the headache intensity responded hour by hour for the first 24 hours, and day by day for the 30 days following the treatment of status migrainosus with four therapeutic approaches commonly used in academic headache centers. The study describes previously unrecognized challenges in defining success and failure in the treatment of status migrainosus.

Methods

Patient recruitment

Patients were recruited from the Hartford Healthcare Headache Center (HHHC) from February 2016 until August 2019. The study aimed to investigate the efficacy of treating status migrainosus under real-life conditions as experienced by physicians seeing patients in the clinic. As such, the only inclusion criteria were the following: a) patients with migraine experiencing a migraine attack fulfilling ICHD-3 criteria for status migrainosus (1) (Figure 1), b) medication overuse headache could be ruled out and c) patients were able to comply with a post-treatment headache diary. There were no other limits such as age, sex, comorbid conditions or current or previous medications.

Figure 1.

International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition criteria for status migrainosus.

Study design

Migraine patients seen at the HHHC were informed about the study and invited to participate. Those who were willing to sign an informed consent were instructed to call the clinic if they experienced a debilitating migraine attack continuing for more than 72 hours (status migrainosus). All patients experiencing status migrainosus were invited to the clinic to receive treatment. Patients were allowed to re-enter the study, with each treatment registered as a separate event. As the purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of real-life treatment choices made by a treating physician, the decision of which treatment option to administer to each patient was made based on the treating physician’s familiarity with the patient rather than randomization according to a predefined study protocol. For this reason, the number of patients studied in each treatment group varies.

Patients were treated with one of the following four commonly used approaches in the treatment of status migrainosus:

Dexamethasone: 4mg orally twice a day for 3 days

Ketorolac: 60mg intramuscularly

Nerve blocks (lidocaine 2%). The following nerves were blocked bilaterally in all patients: Supraorbital, 0.1–0.2ml, supratrochlear, 0.1–0.2ml, auriculotemporal, 1 ml and greater occipital nerve, 2ml.

Naratriptan: 2.5mg orally twice a day for 5 days

Patients were instructed to fill out two headache diaries following treatment. The first diary was an hourly diary with entries once every hour for 24 hours, with time point 0 defined as time of the treatment. Diary entry at hour 24 coincided with the time point for post-treatment day 1. From this point and onwards, patients were instructed to fill out the diary once daily for 30 consecutive calendar days following treatment.

Outcome definitions

The primary outcome is the response rate at 24 hours after the intervention (day 1 post-treatment). Patients were asked to rate their hourly and daily headache intensity on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS). Remission was defined as sustained pain freedom (NRS=0) for a minimum of 48 consecutive hours. Response was afterwards defined as the percentage of treatment attempts that resulted in remission by day 1 post-treatment. The main outcome (response rate) was calculated for all treatment attempts with complete data for day 0–2. We furthermore performed an exploratory analysis to see how the response rate changed if the threshold for time to remission was changed to 2 hours, 12 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours or 96 hours, and when the duration of sustained pain freedom was changed to 1day, 3 days, 4 days, 5 days, 6 days and 7 days.

Data synthesis

Patients were stratified by responder status as either responders or non-responders and by headache frequency into one of the following groups: Chronic migraine (CM): Headache ≥15 days/month and migraine ≥8 days/month; high-frequency episodic migraine (HF): Headache <15 days/month and migraine ≥8 days/month; low-frequency episodic migraine (LF): Migraine <8 days/month.

The hourly and daily change in headache intensity was investigated by a lined scatterplot for each patient that provided eligible 24-hour or 30-day diaries. An eligible diary was defined as a diary with less than 15% missing data. Any intermediary missing values were imputed by last observation carried forward under the assumption that intermediary missing values were due to no progression in the condition. This study was purely descriptive. Thus, no statistical comparisons were made.

Results

One hundred and forty patients consented to participate in the study. Seventy-two patients experienced one or more episodes of status migrainosus and reported to the clinic for a total of 86 treatments. Fifty-four patients provided complete data (day 0–2) for 60 treatment attempts and were included in the primary analysis, whereas 18 patients did not provide sufficient data for 26 treatment attempts and were thus not included in the analysis. Characteristics of each patient are presented in the supplemental material, whereas differences between included and excluded patients are presented in Table 1. Patients that were excluded from the analysis had fewer years lived with migraine, were more likely to have high-frequency episodic migraine, less likely to have received nerve blocks, more likely to have received dexamethasone and more likely to have received two treatments (Table 2). There were 44 eligible 24-hour diaries (Figure 2) and 49 eligible 30-day diaries (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Comparison of included and excluded patients.

| Included in primary analysis | Excluded in primary analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of unique patients | 54 | 18 |

| Total number of treatment attempts | 60 | 26 |

| Number of patients receiving | 6 (11.1%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| two treatments | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.6 (11.7) | 47.4 (8.1) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 2 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Female | 52 (96.3%) | 18 (100%) |

| Current opioid use | 2 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Years with migraine. | 29.4 (13.5) | 23.4 (12.4) |

| mean (SD) | ||

| Migraine frequency, n (%) | ||

| Chronic migraine | 22 (40.7%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| High-frequency episodic | 13 (24.1%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| migraine | ||

| Low-frequency episodic migraine | 19 (35.2%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| Treatments, n (% of treatments) | ||

| Dexamethasone | 13 (21.7%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Ketorolac | 9 (15.0%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Naratriptan | 9 (15.0%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Nerve block | 29 (48.3%) | 10 (38.5%) |

Table 2.

Treatment response for responders versus non-responders stratified by headache frequency and treatment group.

| Total |

Low-frequency episodic migraine |

High-frequency episodic migraine |

Chronic migraine |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder | Non-responder | Responder | Non-responder | Responder | Non-responder | Responder | Non-responder | |

| Dexamethasone | 4 (30.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Ketorolac | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2(100%) | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100%) |

| Naratriptan | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100%) |

| Nerve block | 7 (24.1%) | 22 (75.9%) | 3 (25.0%) | 9 (75.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 2(16.7%) | 10(83.3%) |

| Total | 13 (21.7%) | 47 (78.3%) | 5 (26.3%) | 14(73.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | 11 (73.3%) | 4(15.4%) | 22 (84.6%) |

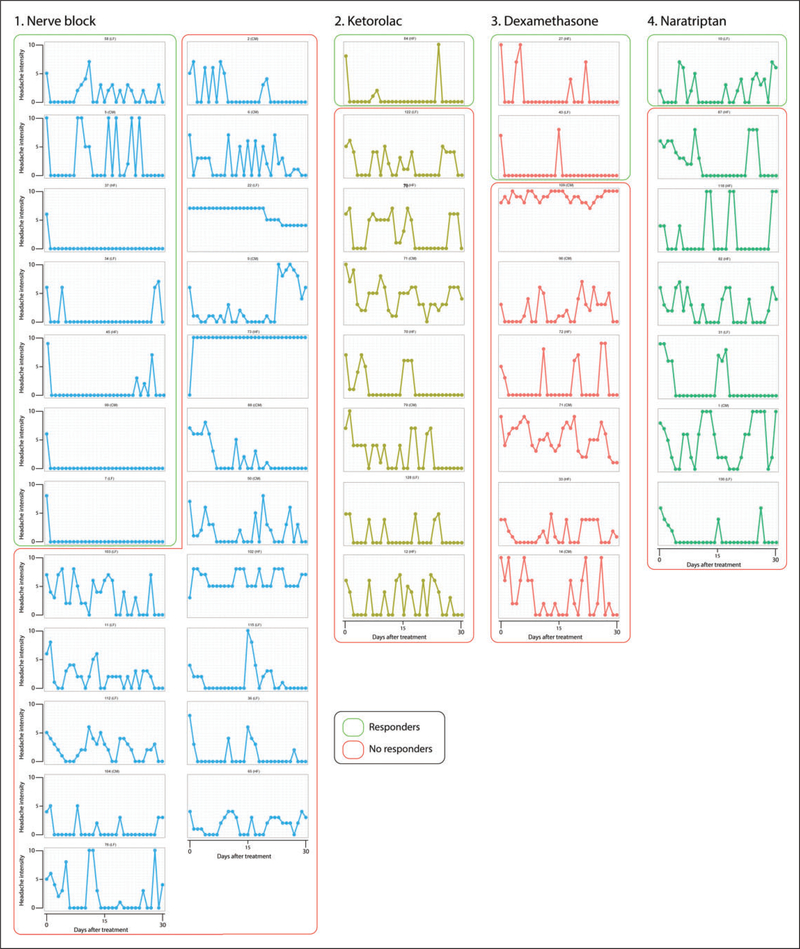

Figure 2.

Hourly reports of headache intensity for the first 24 hours post treatment. Patients classified as responders (i.e. those achieving pain-free status within the first 24 hours and maintaining it for 48 hours) are marked by green lines, whereas those classified as non-responders are marked by red lines. Numbers above each graph depict patients’ study ID, and their migraine type is identified. CM: chronic migraine; HF: high-frequency episodic; LF: low-frequency episodic.

Figure 3.

Daily reports of headache intensity for 30 days post treatment. Patients classified as responders are marked by green lines, whereas those classified as non-responders are marked by red lines. Note the difficulty of identifying responders and non-responders subjectively.

Demographic characteristics

Two men and 52 women with an average age of 48.6 years (SD=11.7) were included in the primary analysis. The average number of years lived with migraine was 29.4 years (SD=13.5). The patients had on average 15.5 headache days per month (SD=8.8), of which 11.1 met criteria for migraine (SD=7.0). Twenty-two patients had chronic migraine, 13 patients had high-frequency episodic migraine and 19 patients had low-frequency episodic migraine. Demographic-, treatment- and outcome characteristics for each of the 54 patients included in the primary analysis are presented in the supplemental material.

Primary analysis

As shown in Table 1, nerve blocks were administered 29 times, dexamethasone 13 times, ketorolac nine times and naratriptan nine times. Remission was achieved following 47 treatments, while the headache remained unremitting despite treatment in 13 treatment attempts. Time to remission ranged from 2 hours to 18 days, with a median of 3 days (interquartile range 1–6.5 days). Pain free period following remission ranged from 2–30 days, with a median of 4 days (interquartile range 3–7.5 days). Table 2 shows the response rate (proportion of participants achieving remission within 24 hours) stratified by treatment group and headache frequency, while Table 3 shows how the response rate varies with different thresholds for time to remission. After 24 hours, 4/13 of dexamethasone treatments (31%) and 7/29 of nerve blocks (24%) resulted in remission while only 1/9 of ketorolac injections (11%) and 1/9 of naratriptan treatments (11%) resulted in remission (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Influence of time to relief on responder rates stratified by treatment group.

| Threshold for time to remission | All patients |

Dexamethasone |

Ketorolac |

Naratriptan |

Nerve block |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responders | Non-responders | Responders | Non-responders | Responders | Non-responders | Responders | Non-responders | Responders | Non-responders | |

| 2 hours | 1 (1.7%) | 59 (98.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (100%) | 1 (3.4%) | 28 (96.6%) |

| 12 hours | 4 (6.7%) | 55 (93.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (100%) | 4 (13.8%) | 25 (86.2%) |

| 24 hours | 13 (21.7%) | 47 (78.3%) | 4 (30.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 7 (24.1%) | 22 (75.9%) |

| 48 hours | 21 (35.0%) | 39 (64.0%) | 5 (38.5%) | 8(71.5%) | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | 10 (34.5%) | 19 (65.5%) |

| 72 hours | 24 (41.0%) | 35 (59.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 7 (53.8%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | 12 (41.4%) | 17 (58.6%) |

| 96 hours | 30 (50.0%) | 30 (50.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 7 (53.8%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 14 (48.3%) | 15 (51.7%) |

Figure 4.

Treatment success rate with varying thresholds for time to remission. The graph depicts the percentage of treatment attempts that can be classified as successful (remission is achieved), when the time to remission is increased from 2 hours to 96 hours. X-axis: Threshold for time to remission. Y-axis: Percentage of treatments where remission was achieved.

The change in hourly and daily headache intensity for individual patients with eligible 24-hour and 30-day diaries is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, where responders are those who achieved remission within 24 hours. As shown in Figure 2, six of those classified as non-responders achieved headache free status during the 24-hour hourly observation period. Nevertheless, they were classified as non-responders because the headache recurred by post-treatment day 1. As shown in Figure 3, 29 of those classified as non-responders (because they did not achieve remission lasting 48 hours by day 1) experienced remission sometime during the 30-day observation period.

Exploratory analysis

Changing the threshold to 48 hours, 5/13 of dexamethasone treatments (38%), 10/29 of nerve blocks (34%), 4/9 of ketorolac injections (44%) and 2/9 of naratriptan treatments (22%) would have resulted in remission. With a threshold of 72 hours to remission, 6/13 of dexamethasone treatments (46%), 12/29 of nerve blocks (41%), 5/9 of ketorolac injections (56%) and 2/9 of naratriptan treatments (22%) would have resulted in remission. Finally, with a threshold of 96 hours to remission, 6/13 of dexamethasone treatments (46%), 14/29 of nerve blocks (48%), 5/9 of ketorolac injections (56%) and 5/9 of naratriptan treatments (44%) would have resulted in remission.

Discussion

This is the first study to detail an hour by hour and day by day change in headache intensity in migraine patients treated for status migrainosus in a tertiary headache clinic. Using a diary to capture treatment effect prospectively, we found that the overall success rate of rendering patients’ pain-free within 24 hours of treatment and maintaining the pain-free status for 48 hours is 13/60 (22%), and that the success rate is similar for dexamethasone (4/13, 31%), nerve blocks (7/29, 24%), ketorolac (1/9, 11%) and naratriptan (1/9, 11%). These observations suggest that current treatment approaches to terminating status migrainosus are not satisfactory. As can be expected, the success rate depends on time to remission and duration of the pain-free period. The longer we allowed the treatment to begin to work and the patients to become pain-free (i.e. 2, 12, 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours), the more likely a treatment was to result in a pain-free status for at least 48 hours, with treatments approaching equivalent success rates on post-treatment day 4. In contrast, the duration of maintaining the pain-free status (once achieved) was inversely related to the success rate. When the requirement for the pain free duration was increased from 1 to 7 days, the percentage of responders declined from 23% to 13% if remission was to be achieved within 24 hours and from 53% to 18% if remission was to be achieved within 96 hours. This time-sensitive and wide variation in what can be considered a “success” calls to attention the need to develop a expert consensus on how to define treatment response for status migrainosus.

Considering that our overall rate of success for terminating attacks within 24 hours was achieved after treatment sessions in the clinic, an overall success rate of 22% could readily be seen as disappointingly lower than expected given that patients made the effort to come to the clinic and that some of their treatment approaches included parenterally-administered drugs. Two factors may contribute to this low rate of success. The first is time of intervention from onset of attack and the second is the complexity of the patient. As is widely accepted by now, the chances of achieving a headache-free status with acute therapy is significantly lower when treatment is administered hours, rather than minutes after attack onset (6,7). By definition, intervention was administered days rather than hours or minutes after migraine onset in the current study. If the same principle applies, it is reasonable to expect a low success rate. For comparison, if triptans are taken when the headache is moderate to severe (rather than immediately after onset of headache) the percent of patients achieving sustained freedom from pain at 24 hours (10–30%) (8) is similar to the 22% reported here. In contrast, when triptan treatment is initiated early, the 24-hour sustained pain-free rate increases twofold (6). An additional explanation for our low success rate may be the fact that all participants had failed attempts to terminate their migraine attacks at home with triptans and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) prior to their treatment in the clinic. Consequently, all attacks treated as part of this study were triptan- and NSAID-unresponsive. It is widely recognized that attacks unresponsive to the first treatment approach are more likely to be resistant to a second treatment approach than attacks responsive to first treatment – potentially reflecting the level of attack complexity.

As shown in Table 3, patients treated with dexamethasone or nerve blocks were more likely to achieve a pain-free status within 24 hours than those treated with ketorolac or naratriptan. These differences, however, did not hold true for 48, 72 and 96 hours post treatment. As time post-treatment progressed, patients treated with ketorolac (and to a lesser extent naratriptan) were equally likely to achieve pain-free status as those treated with dexamethasone or nerve blocks. While the mechanisms of action of these treatment approaches are largely unknown, it is reasonable to suggest that drugs that block the flow of pain signals from peri-cranial nerves (i.e. lidocaine), reduce inflammation (i.e. dexamethasone, ketorolac) or act as 5HT1b/1d agonists (i.e. naratriptan) terminate migraine by interacting directly and indirectly with different components of the trigeminovascular pathway, the immune system, and the brain. Given our limited understanding of the mechanisms of actions of these treatment approaches, however, we cannot offer an evidence-based explanation for the faster onset of action of dexamethasone and nerve blocks compared to ketorolac and naratriptan. Theoretically, one can speculate that a nerve block produces an immediate effect on the flow of pain signals along the blocked nerves and that dexamethasone reaches maximal level in the plasma earlier than ketorolac and naratriptan. This explanation, however, is too simplistic and unlikely as most patients did not report treatment effects of nerve blocks until hours after the numbness was lifted, whereas dexamethasone, ketorolac and naratriptan reach maximal plasma concentration in 1–2 hours (9–11). Regardless of our inability to explain these time differences, it may be worthwhile using these data to set patients’ expectations correctly by letting them know when to expect noticing an improvement in their headache following each treatment approach.

As shown in Table 4, the proportion of patients achieving a pain-free status at 2, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours increased steadily from 2% to 8% to 23% to 37% to 43% to 53%, respectively. These findings emphasize the need for a consensus definition on how much time can pass before headache cessation can no longer be attributed to medication in status migrainosus. At first glance, it is tempting to suggest that criteria for a positive treatment response to status migrainosus should allow 48 to 72 or even 96 hours for the patients to become pain free. While it might make sense mechanistically, as irritated peripheral nerves and affected brain areas need time to “recover” (12–17), the suggestion is clinically problematic as it introduces the possibility that the treated headache may have ended spontaneously. This is especially apparent at the 96 hour mark, where all four treatments show similar success rates. Further justifying caution in proposing to extend the time for remission are studies showing that a noticeable percentage of migraine patients experience migraine attacks that last for more than 72 hours, with the prevalence at 3% in one study (18) and 21.7% in another (19). Accordingly, before we can consider the 53% of the patients who reported being pain-free 96 hours after treatment as responders, one must first accept the possibility this could have been a “regular” migraine attack lasting 7 days (3 days before and 4 days after treatment), with a spontaneous remission. Although unlikely, this possibility cannot be refuted or supported in the absence of more data on the treatment outcome of status migrainosus and the duration of untreated attacks.

Table 4.

Influence of time to relief versus duration of sustained relief on responder rates.

| Duration of relief | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | 5 days | 6 days | 7 days | |

| Time to relief | |||||||

| 2 hours | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| 12 hours | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (6.7%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| 24 hours | 14 (23.3%) | 13 (21.7%) | 13 (21.7%) | 11 (18.3%) | 10(16.7%) | 9 (15.0%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| 48 hours | 22 (36.7%) | 21 (35.0%) | 20 (33.3%) | 17(28.3%) | 13 (21.7%) | 12 (20.0%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| 72 hours | 26 (43.3%) | 24 (40.0%) | 21 (35.0%) | 18(30.0%) | 13 (21.7%) | 12 (20.0%) | 8 (13.3%) |

| 96 hours | 32 (53.3%) | 30 (50.0%) | 26 (43.3%) | 23 (38.3%) | 17 (28.3%) | 16 (26.7%) | 11 (18.3%) |

Finally, as also shown in Table 4, the proportion of patients whose pain-free status is sustained for 1, 2 and 3 days remains stable but declines steadily in days 4, 5, 6 and 7. These findings raise the possibility that the sustained pain-free duration of 1, 2, or 3 days should be considered in the definition of responders. Of note, we interpret the steady decline in the proportion of patients whose pain-free status is maintained for 4–7 days as those experiencing onset of new migraine attacks. But regardless of our proposed interpretations, this study points to a critical need to employ standardized outcome measures to evaluate treatment efficacy as well as a need for a consensus definition on outcome measures for status migrainosus.

Lastly, a note on the reasoning behind the definition of the primary endpoint: We decided to define our primary outcome as pain freedom achieved within 24 hours and sustained pain freedom for at least 48 consecutive hours. one might ask why 24 hours and not 2 hours or 12 hours, and why complete pain freedom instead of a 50% reduction in headache intensity, or a reduction to mild headache. Although the International Headache Society has published guidelines for conducting trials on acute and preventive migraine treatments, there are currently no recommendations on the condition status migrainosus, which is a complication of migraine. We therefore had to create our own definition. We decided on complete freedom of pain instead of a 50% reduction, because complete freedom of pain is in accordance with the recommended primary outcome for trials on acute treatment (20). For complete remission of pain, we decided on 24 hours instead of 2 hours because of the criteria for status migrainosus. Remission of pain for up to 12 hours is accepted in the current criteria. We decided on 24 hours to allow for a fluctuating reduction throughout the first 24 hours post-treatment (as demonstrated in Figure 2). We do, however, acknowledge that our definition includes elements of arbitrariness. Both a 50% reduction or a reduction to mild headache would have made sensible alternatives to pain freedom. These choices, though, would have been just as arbitrary as pain freedom, which is why we opted for a definition resembling the recommended primary outcome in other guidelines. We do however feel the need to state that we do not claim to be the judges of the “correct” definition of treatment response. On the contrary, our purpose is to encourage a debate and the development of an expert consensus.

Limitations

The main limitation is that this is an observational study without randomization or a placebo group. It is therefore with a limited capability that inferences can be made about treatment efficacy in regards to reduction in headache intensity and headache duration. Sample sizes for each individual treatment arm were small, which is why the results are at risk of being biased by sampling error.

Conclusion and future directions

Our findings suggest that current treatment approaches for the management of status migrainosus do not deliver satisfactory outcomes. There is a need to develop consensus guidelines on how to conduct trials for status and migrainosus and how to define outcomes to ensure future studies of high quality. Furthermore, there is a need for randomized, placebo-controlled trials on interventions investigating the efficacy of treating migraine attacks meeting ICHD criteria for status migrainosus. Future studies should employ a prospective design and preferably use electronic headache diaries to reliably capture data.

Supplementary Material

Key finding.

If treatment success for migraine patients in status migrainosus is defined as being pain free within 24 hours, with sustained pain freedom for 48 hours, current treatment approaches in the clinic deliver unsatisfactory results.

There is a need for an international consensus on how to define trial outcomes for status migrainosus to facilitate future research and better outcomes.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the Migraine Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beltramone M and Donnet A. Status migrainosus and migraine aura status in a French tertiary-care center: An 11-year retrospective analysis. Cephalalgia 2014;34:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vecsei L, Szok D, Nyari A, et al. Treating status migrainosus in the emergency setting: What is the best strategy? Exp Opin Pharmacother 2018; 19: 1523–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozen TD. Emergency department and inpatient management of status migrainosus and intractable headache. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015; 21: 1004–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcus DA. Treatment of status migrainosus. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2001; 2: 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanteri-Minet M, Mick G and Allaf B. Early dosing and efficacy of triptans in acute migraine treatment: The TEMPO study. Cephalalgia 2012; 32: 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burstein R, Collins B and Jakubowski M. Defeating migraine pain with triptans: A race against the development of cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol 2004; 55: 19–26.14705108 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Roon KI, et al. Triptans (serotonin, 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: Detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Cephalalgia 2002; 22: 633–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAleer SD, Majid O, Venables E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of ketorolac following single intranasal and intramuscular administration in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 47: 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tfelt-Hansen P, De Vries P and Saxena PR. Triptans in migraine: A comparative review of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and efficacy. Drugs 2000; 60: 1259–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Sullivan BT, Cutler DJ, Hunt GE, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone and its relationship to dexamethasone suppression test outcome in depressed patients and healthy control subjects. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41: 574–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, et al. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol 2000; 47: 614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strassman AM, Raymond SA and Burstein R. Sensitization of meningeal sensory neurons and the origin of headaches. Nature 1996; 384: 560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burstein R, Jakubowski M, Garcia-Nicas E, et al. Thalamic sensitization transforms localized pain into widespread allodynia. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstein R, Yamamura H, Malick A, et al. Chemical stimulation of the intracranial dura induces enhanced responses to facial stimulation in brain stem trigeminal neurons. J Neurophysiol 1998; 79: 964–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burstein R, Cutrer MF and Yarnitsky D. The development of cutaneous allodynia during a migraine attack clinical evidence for the sequential recruitment of spinal and supraspinal nociceptive neurons in migraine. Brain 2000; 123: 1703–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burstein R, Noseda R and Borsook D. Migraine: Multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 6619–6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh TD, Cutrer FM and Smith JH. Episodic status migrainosus: A novel migraine subtype. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pryse-Phillips W, Aube M, Bailey P, et al. A clinical study of migraine evolution. Headache 2006; 46: 1480–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diener HC, Tassorelli C, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of acute treatment of migraine attacks in adults: Fourth edition. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 687–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.