Vellieux et al recently reported two coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients showing a unique EEG pattern, i.e., non-reactive bifrontal monomorphic diphasic periodic delta waves, and suggested that this pattern could be typical of COVID-19 brain dysfunction (Vellieux et al., 2020).

Here we report the EEG findings in 15 patients with suspected COVID-19 related encephalopathy, stemming from a population of 873 patients admitted to our hospital in a 3 months period (from March 1 to May 31, 2020) with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

In detail, these were 6 males and 9 females, with a mean age of 64.6 years (range: 47–79 years). The mean delay between the COVID-19 infection and the onset of neurological symptoms prompting the execution of the EEG was 8 days. The main neurological symptoms included confusion (11 patients), aphasia (1 patient), and impairment of consciousness (4 patients). Out of the 4 patients with impairment of consciousness, two had post-anoxic coma after respiratory distress, one multi-organ failure, and one critical illness myopathy/neuropathy with brainstem involvement. Comorbid conditions likely to influence the EEG tracings were present in 5 cases and included cognitive decline (2 patients), previous limbic encephalitis (1 patient), multi-organ failure (1 patient) and frontal metastasis (1 patient).

EEG recordings were performed with a Nihon Kohden Neurofax EEG 1200 K instrument using 18 scalp electrodes positioned according to the standard 10–20 international system. All the records had a EKG. The O2 saturation was also checked at the time of the EEG and was >93% in all cases.

Patients were stimulated by verbal commands, opening of the eyes, and when arousals were not evoked, noxious stimuli like sternal rub and toe compression were applied.

Arousals were defined according to standard criteria as abrupt shift in frequency of background activity, lasting for 3 s or more that may have included theta, alpha and/or frequencies >16 Hz but no spindles.

All EEG recordings were analyzed by two experienced neurologists (RM, EP) trained in EEG interpretation.

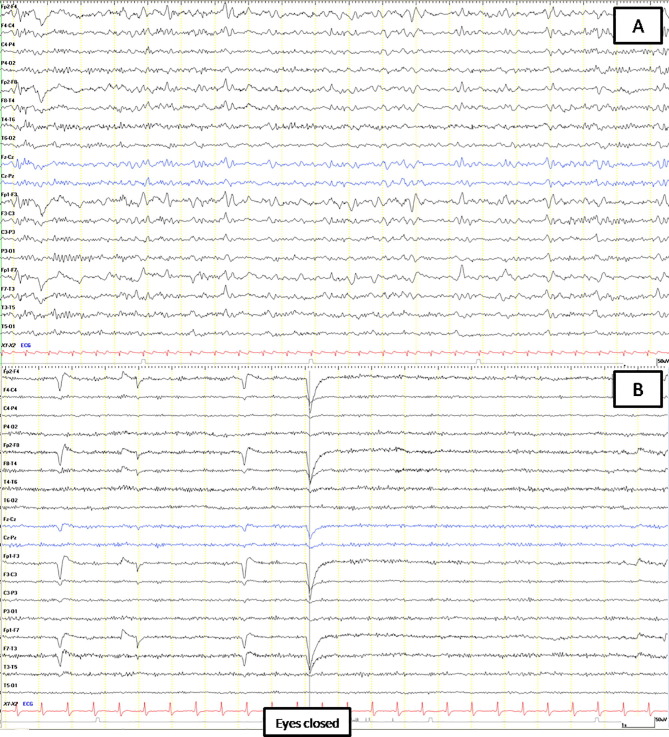

The EEGs were abnormal in all cases. In the two patients with post-anoxic coma, the EEG showed in one case severely suppressed activity on the first day after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and in the second case discontinued activity compatible with post-anoxic status epilepticus on the third day after ROSC. In the remaining 13 patients the EEG abnormalities included slowing of the background activity ranging from 4 to 8 Hz (with theta prevalence in 5 cases and intrusions of theta/delta activity in 4 cases), focal theta or delta waves predominantly over the frontal or central regions (3 patients) and frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA) (1 patient) (Fig. 1 A). Reactivity to external stimuli and eye opening/closure was absent in 10 cases (Fig. 1B). The severity of slowing of the background activity varied widely among patients and correlated with the clinical picture. No epileptiform abnormalities or triphasic waves were observed. Repeat EEGs were avaiable in 3 patients and showed marked improvement of posterior activity, in accord with the improvement of neurological symptoms.

Fig. 1.

EEG of two COVID-19 positive patients, both clinically alert and conscious but confused. (A) EEG of the first patient shows a disorganized alpha-theta background activity with frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA). (B) EEG of the second patient, who in addition showed non-fluent aphasia, is characterised by monomorphic diffuse alpha-like rhythm without reactivity after eyes closure.

CT scans (8 cases), MRI (6 cases) and spinal tap (5 cases) were also performed. These tests were normal in all cases except for mild MRI T2 hyperintensity in the white matter in two cases and slight elevation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein in one patient. SARS-CoV-2 was not detected in the CSF in any case.

EEG findings in SARS-CoV-2 infection have been rarely reported and largely considered non-specific (Flamand et al., 2020, Vellieux et al., 2020). Indeed, EEG in acute encephalopathies may reveal different degrees of background slowing, with or without triphasic waves and FIRDA and these patterns are believed to reflect an underlying structural or metabolic disorder; however, there is limited evidence linking specific EEG abnormalities with plausible causative factors. Absent EEG reactivity with bifrontal monomorphic periodic delta waves was reported by Vellieux et al., who suggested that this pattern could be specific of COVID-19 related encephalopathy (Vellieux et al., 2020). Accordingly, in our series, apart from the 2 post-hypoxic patients, the EEG characteristics were quite homogeneous, though non-specific, and included non-reactive, slow, monomorphic and disorganized background activity. We may hypothesize that, while the slowing of background activity may suggest a diffuse cortical involvement, the lack of reactivity to external stimuli along with the monomorphic pattern of the EEG and occasional frontal delta waves may denote a concomitant subcortical or brainstem dysfunction (Sutter et al., 2013). The pathophysiology of these changes remains elusive, however, and a multifactorial origin has been postulated although a metabolic/hypoxic mechanism seems unlikely on the basis of our EEG findings (Flamand et al., 2020). Notwithstanding, the EEG remains the most sensitive tool to disclose the existence of a COVID-19 related encephalopathy, taking into account the limited usefulness of other diagnostic tests (Paterson et al., 2020). In our experience the EEG was performed in only a minority of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in those showing overt signs of CNS involvement. It may be argued that a more widespread use of the EEG would have disclosed a higher rate of neurological complications.

In conclusion, our observations confirm the high sensitivity of the EEG and its localization value in encephalopathies, contributing to unravel also mild cases of COVID-19 related brain dysfunction. In detail, we have shown that COVID-19 related encephalopathy may be associated with a rather homogeneous EEG pattern consisting of a diffuse slowing of the background activity and loss of reactivity to external stimuli. Whether or not these EEG findings may be specific for COVID-19 related encephalopathy is unknown and deserves further investigation.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

EP and RM analyzed EEG and wrote the manuscript. FB and PT suggested and revised the manuscript.

LV, IM, MT, LM, UP, PR gave their clinician expertise.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Flamand M., Perron A., Buron Y., Szurhaj W. Pay more attention to EEG in COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(8):2062–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R.W., Brown R.L., Benjamin L., Nortley R., Wiethoff S., Bharucha T. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020;(Jul):awaa240. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter R., Stevens R.D., Kaplan P.W. Clinical and imaging correlates of EEG patterns in hospitalized patients with encephalopathy. J Neurol. 2013;260:1087–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6766-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellieux G., Rouvel-Tallec A., Jaquet P., Grinea A., Sonneville R., d’Ortho M.P. COVID-19 associated encephalopathy: is there a specific EEG pattern? Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(8):1928–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]