Abstract

The “International Biomarkers Workshop on Wearables in Sleep and Circadian Science” was held at the 2018 SLEEP Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. The workshop brought together experts in consumer sleep technologies and medical devices, sleep and circadian physiology, clinical translational research, and clinical practice. The goals of the workshop were: (1) characterize the term “wearable” for use in sleep and circadian science and identify relevant sleep and circadian metrics for wearables to measure; (2) assess the current use of wearables in sleep and circadian science; (3) identify current barriers for applying wearables to sleep and circadian science; and (4) identify goals and opportunities for wearables to advance sleep and circadian science. For the purposes of biomarker development in the sleep and circadian fields, the workshop included the terms “wearables,” “nearables,” and “ingestibles.” Given the state of the current science and technology, the limited validation of wearable devices against gold standard measurements is the primary factor limiting large-scale use of wearable technologies for sleep and circadian research. As such, the workshop committee proposed a set of best practices for validation studies and guidelines regarding how to choose a wearable device for research and clinical use. To complement validation studies, the workshop committee recommends the development of a public data repository for wearable data. Finally, sleep and circadian scientists must actively engage in the development and use of wearable devices to maintain the rigor of scientific findings and public health messages based on wearable technology.

Keywords: biomarker, wearable, circadian misalignment, sleep tracker, insufficient sleep, short sleep, sleep loss, sleep disorders, actigraphy, polysomnography

Statement of Significance.

This White Paper summarizes the 2018 Sleep Research Society sponsored workshop, “International Biomarkers Workshop on Wearables in Sleep and Circadian Science.” Workshop participants discussed barriers and opportunities for using wearables in sleep and circadian science. Poor validation of current wearable technology was identified as the primary barrier inhibiting widespread use of wearables in sleep and circadian science. The committee proposed a set of best practices for validation studies to help overcome this barrier. Despite current limitations, applying wearable technologies to large, prospective studies conducted in free-living environments has great potential to advance the sleep and circadian fields. Continued development and validation of wearables will facilitate rigorous application of wearables to the ongoing research efforts in the sleep and circadian fields.

Introduction

The Sleep Research Society and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that adults aged 18–60 years regularly obtain 7 or more hours of sleep per night to promote optimal health [1, 2]. Yet, sleep disorders [3] have become epidemic with ~35% of adults in the United States sleeping less than 7 h per night, 30% sleeping less than 6 h per night, and in some specific groups, such as active military personnel, rates of insufficient sleep exceed 40% [4–7]. Findings from epidemiological and laboratory controlled trials consistently show insufficient sleep is associated with adverse health and safety outcomes including inflammation, stress, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases, drug abuse, poor quality of life, and risk of accidents [8–22]. Furthermore, short sleep durations are associated with increased mortality [23, 24]. Despite these links between insufficient sleep and negative health outcomes, many primary care providers fail to diagnose or recognize sleep disorders, and estimates suggest that undiagnosed sleep disorders are more prevalent than diagnosed sleep disorders [25, 26].

Circadian misalignment is the mistiming of environmental or behavioral cycles relative to the circadian timing system, or of mistiming in components of the circadian system. Shift-workers comprise ~20% of the workforce in industrialized nations and are often required to maintain wakefulness and alertness during their biological night to perform work-related duties, inducing circadian misalignment [27–29]. A more common form of circadian misalignment is social jetlag, which is quantified as the absolute difference between mid-sleep time on workdays versus mid-sleep time on free days [30]. The larger the difference in sleep timing on workdays versus free days, the more severe the social jetlag. Estimates from a study with over 65,000 entries from the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire database show ~69% of the represented population reported 1 h of social jetlag and 33% reported 2 h or more of social jetlag [31]. Like insufficient sleep, circadian misalignment is epidemic and is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes including risk of cancer, obesity, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, risk of accidents, and psychiatric disorders [32–34].

The sleep and circadian fields have made extraordinary progress understanding the basic mechanisms regulated by the sleep and circadian systems and the health consequences of insufficient sleep and circadian disruption. Yet, the lack of accessible and objective tools for quantifying sleep and circadian physiology outside of laboratory settings has limited the translation of these scientific advances to improvements in human health [35]. As such, the Sleep Research Society (SRS) has sponsored a series of International Workshops on Biomarkers in Sleep and Circadian Science. The first workshop occurred in 2015 and was a joint SRS-National Institutes of Health workshop that identified an immediate need and a long-term benefit of developing biomarkers of acute sleep deficit, chronic sleep deficit, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and circadian disruption and identified multiple platforms for biomarker development ranging from omics to wearable technologies [35]. Key outcomes of the 2016 and 2017 workshops were the development of consensus definitions for “chronic insufficient sleep” and “circadian misalignment,” and outlining goals for developing biomarkers of chronic insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment.

This White Paper summarizes the 2018 workshop, “International Biomarkers Workshop on Wearables in Sleep and Circadian Science,” that brought together experts in consumer sleep technologies, medical devices, sleep and circadian physiology, clinical translational research, and clinical practice. The primary goals of the workshop were: (1) characterize the term “wearable” for use in sleep and circadian science and identify relevant sleep and circadian metrics for wearables to measure; (2) assess the current use of wearables in sleep and circadian science; (3) identify current barriers for applying wearables to sleep and circadian science; and (4) identify goals and opportunities for wearables to advance sleep and circadian science.

What is a Wearable, and What Metrics Relevant to Sleep and Circadian Science Should Wearables Measure?

Wearables for sleep and circadian science

Wearables exploded onto the consumer market in the early 2010s, and today, wearables are nearly ubiquitous in modern society. An estimated ~350 million wearable devices will be shipping in 2020, up from 224 million in 2018 [36]. Considering their broad capabilities, it is essential to identify the most relevant metrics for wearables to measure in the context of sleep and circadian science.

Wrist-worn actigraphy is an accepted and commonly used wearable designed to assess sleep and wakefulness. Actigraphy detects body movements by accelerometry (the measurement of acceleration), and some research-grade actigraphs measure light exposure. Algorithms (some publicly available) automatically score actigraphy data [37–41], facilitating the incorporation of accelerometry based data into consumer sleep wearables. In addition to actigraphy, there are a range of metrics that sleep and circadian scientists can utilize from wearable technologies such as geographical location, body temperature, heart rate, skin conductivity, blood oxygen levels, and mood assessments. Additionally, some devices can monitor air quality, noise levels, and ambient temperature. Such devices are placed nearby the user to collect data from the user and the user’s local environment, and therefore are defined as “nearables.” The concept of wearables can also be extended to “ingestibles,” miniaturized devices that transmit information, such as core body temperature, and are ingested by the user like a pill. For this White Paper, the term wearables extends to nearables and ingestibles.

Gold standard methods of quantifying sleep

Polysomnography (PSG) is the most reliable and valid measure of sleep and is therefore the current gold standard for quantifying sleep. PSG is most often performed in sleep laboratories and involves the application of electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes to the scalp, electromyography (EMG) electrodes to the facial muscles and limbs, electrooculography (EOG), electrocardiography (EKG), pulse oximetry, thoracic and abdominal belts, and nasal (or oro-nasal) flow sensors to measure breathing patterns. Sleep staging is determined from brain EEG, EOG, and chin EMG. As such, PSG is not a direct measure of sleep per se, but rather a quantification of cortical and peripheral physiological changes that occur during sleep.

A challenge in adopting PSG to wearable technology is the complex sleep scoring criteria [42]. Automated PSG scoring is not an adequate replacement for sleep technologists due to the multifaceted nature of PSG interpretation [43]. Furthermore, PSG is generally conducted for 1–5 nights in clinical and research settings and is therefore not designed to track individual sleep patterns longitudinally. Thus, within the state of current technology, complete PSG is not a viable candidate for a wearable metric of sleep. It is, nonetheless, the gold standard against which any other device purporting to measure sleep should be assessed. Additionally, aspects of PSG, such as pulse oximetry and/or limited EEG channels, have the potential to be incorporated into wearable devices.

Gold standard methods of quantifying circadian physiology

The two most common protocols for measuring circadian outcomes in humans are the constant routine and forced desynchrony. The following references summarize established human circadian protocols [44, 45]. The constant routine is the gold standard for calculating circadian phase, the forced desynchrony is the gold standard for calculating circadian period and for separating circadian regulation from behavioral sleep-wake regulation, and both protocols can be used to calculate circadian amplitude. Twenty-four hour melatonin or core body temperature assessments are the gold standard measures for human circadian timing [44]. Melatonin is easily measured in saliva, blood, and urine. However, light exposure inhibits the multisynaptic pathway regulating melatonin secretion, thereby reducing melatonin levels. Therefore, samples for melatonin analysis must be collected every 30–60 min under dim light conditions (e.g. <8 lx). There is a validated home kit for conducting 24 h circadian melatonin assessments in dim light conditions, and while not amenable to wearables, such a kit provides the opportunity to validate wearables against the gold standard 24 h circadian melatonin rhythm outside of laboratory settings [46]. Historically, rectal thermistors were used to assess 24 h core body temperature to identify the timing of core body temperature minimum [44]. Less invasive ingestible capsules that telemetrically monitor internal body temperature are now available. Since posture, physical activity, and sleep all impact core body temperature, these factors must be controlled to facilitate accurate assessments of 24 h core body temperature rhythms, making applications of these ingestibles outside of the laboratory challenging. Importantly, markers of circadian rhythms must be validated using these gold standards.

Workshop consensus opinion: sleep and circadian metrics for wearables to measure

Sleep research employs features that are indicative of sleep duration, timing, efficiency, quality, regularity, satisfaction, and breathing and status of the Central and Autonomous Nervous System [47]. Sleep metrics that can potentially be quantified via wearables for this purpose are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sleep-relevant metrics for wearable devices

| Sleep duration | Sleep quality | EEG | Physiological | Breathing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Total sleep time (TST) [48] • Time in bed (“lights out” to “lights on”) |

• Wake after sleep onset (WASO) [48] • Sleep onset latency [48] • Percent sleep efficiency [48] • REM latency (stage R latency) [48] • Periodic limb movements [48] |

• Sleep staging [48] • Sleep spindles [48] • Slow wave activity [48] • Slow oscillations [49] |

• Heart rate (beats per minute) • Heart rate variability [50, 51] • Blood pressure • Body position [48] |

• Blood oxygen saturation [48] • Apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) [48] • Respiratory rate and effort [48] • Snoring [48] • Nasal pressure [48] • Airflow [48] |

Since circadian misalignment incorporates components of the endogenous circadian system and components of environmental and behavioral cycles, relevant circadian metrics for wearables include: (1) markers of the endogenous circadian rhythm and (2) external cues, also known as Zeitgebers, that influence circadian timing (Table 2). Some circadian metrics overlap with sleep, such as the segment of the day with the lowest activity, which could be inferred as sleep. Pairing wearables with a user interface or mobile device (e.g. smartphone) to administer questionnaires and collect data on many of the environmental and behavioral metrics (e.g. ecologic momentary assessments) will be required, whereas other metrics, such as timing of exercise, can be inferred from a wearable itself without user input.

Table 2.

Circadian-relevant metrics for wearable devices

| Environmental | Behavioral | Physiological |

|---|---|---|

| • 24 hour light exposure pattern (intensity and wavelength) [52] • Geographical location (e.g. global positioning system) • Ambient temperature of local environment (e.g. bedroom temperature) |

• Sleep onset latency [48] • Waketime • Timing of energy intake including alcohol and caffeine • Timing of supplement and medication intake • Timing of physical activity |

• Heart rate (beats per minute) • Blood pressure • Skin temperature • Core body temperature |

Review of current wearables used in sleep and circadian science

Overview of wearable devices quantifying sleep

Among current wearables, wrist-worn devices, including actigraphy, are most widespread, and most often use accelerometry-based data. Estimated metrics typically include bedtime, waketime, sleep duration, and sometimes include sleep onset latency, wakefulness after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency. Newer multisensor devices integrate additional metrics such as heart rate, skin conductance, skin temperature, and blood oxygenation to supplement the accelerometer data. Other wearables are worn at the upper arm and were originally designed to estimate energy expenditure—particularly in athletes—by combining accelerometer data with sensors for body temperature and galvanic skin response. Because these devices utilize similar technology as actigraphy (i.e. accelerometry), many have been tested for detection of sleep metrics [53, 54]. Though less common than wrist/arm-worn devices, wearables placed at other locations on or near the body have been purported to measure sleep. Examples include pedometers, chest sensors, rings, and mattress sensors. Finally, in addition to devices that use accelerometers to estimate sleep, technological developments in ambulatory electrophysiology have led to consumer-based devices that quantify sleep via EEG (see de Zambotti et al. for a recent review [55]).

Overview of wearable devices quantifying circadian timing

Fewer wearable devices target the assessment of circadian timing, and even fewer of these devices are commercially available and designed for consumer use. Many of these devices focus on measurements of core body temperature, or use peripheral body temperature to estimate core body temperature. These data are then used to estimate attributes of circadian rhythms such as circadian period, amplitude, and core body temperature minimum. In place of the gold standard rectal thermistors to measure core body temperature, less invasive approaches include the use of ingestible capsules that telemetrically monitor internal body temperature and peripheral skin temperature sensors. Three devices under development have used temperature sensors on the head (e.g. in a headband or helmet) to estimate cerebral temperature based on mechanisms of bioheat transfer [56–58]. Other devices have embedded temperature sensors in a multisensor vest [59] or a flexible wireless skin temperature system that can be placed directly on the body [60]. Results from validation studies on many of these devices are mixed [61, 62].

Emerging evidence suggests data acquired from research-grade actigraphy may also have applications for circadian physiology. In particular, continuous light and 24-h rest-activity pattern data show promise in predicting circadian phase and period in healthy adults [63]. Research validating this in night shift workers is underway [64, 65]. While few wrist-worn consumer-based wearables currently have integrated light sensors, this may represent untapped opportunities for consumer-based sleep devices to extend their applications to circadian rhythms.

Need for Independent Validation of Wearables to Support and Advance Sleep and Circadian Science

Workshop consensus opinion: validation of current wearables in sleep and circadian science

Only a subset of the commercially available wearable devices has been independently tested for validity against the gold standards (for extensive reviews, see the following [55, 66]), and some of the validated devices are no longer available due to company closures or product discontinuation. Furthermore, most validation trials are limited to small samples of young adults with adequate sleep schedules and no sleep disorders. Wearable validation as a whole is far behind the pace of the wearable industry and is inadequate to support the growing use of wearable devices in research and clinical practice.

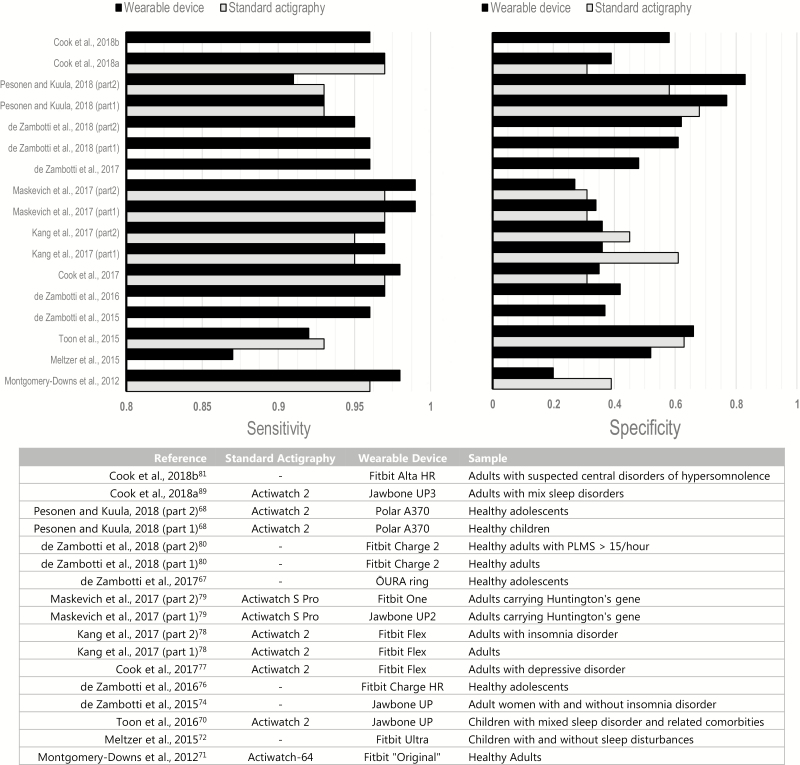

With few exceptions [67–70], wearable devices overestimate PSG total sleep time [53, 71–81] and underestimate PSG wakefulness after sleep onset [72–74, 76–79, 81]. On an epoch-by-epoch (EBE) basis, wearable devices tend to have high sensitivity (ability to correctly classify PSG sleep epochs) and poorer specificity (ability to correctly classify wake epochs). Sensitivity is usually narrow and greater than 90%, while specificity is wider (20%–80%) averaging ~50%, for consumer- and research-grade devices (Figure 1). This holds true for wearable devices in children and adults, and in the presence of sleep pathologies (e.g. apnea, hypersomnolence, insomnia), using accelerometry-based or multisensor wearables. Similar to actigraphy [82], the performance of other wearables decreases with the increase in PSG identified sleep disruption; this, however, has been directly tested in just a few studies using consumer sleep wearables [67, 74]. Other factors including sleep disorders and age [70, 73] also affect device performance, but results are mixed and further analysis of factors potentially affecting device performance is needed (e.g. alcohol consumption).

Figure 1.

Sensitivity and specificity (upper panel) for different wearable devices tested against PSG. Sensitivity and specificity for research/clinical-grade actigraphy is also presented when standard actigraphy and wearable devices were simultaneously tested against PSG. Information about devices and population used in each study are displayed in the bottom panel. Only data for wearables used in ‘normal’ setting are presented. Refer to the text for discussion about the ‘sensitive’ setting.

The limited validation of wearables against gold standards is the major barrier in applying wearables to sleep and circadian research and to clinical sleep medicine [83]. Wearable technology is an unregulated space, and most consumer wearable devices are not approved by the FDA and are therefore categorized as “wellness” products. This may change with new initiatives such as the Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert - https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program). Some wearable companies are starting to partner with research and clinical actigraphy manufacturers to position wearable technology for FDA approval to support medical research, but extensive development is still needed. Validation of wearables for research and clinical use must be conducted using the established sleep and circadian gold standard protocols. Testing or comparing wearable devices against actigraphy or other wearables that may include EEG or other components of PSG may provide useful data under some circumstances; however, this type of analysis is not adequate for validation. Furthermore, multi-night in-lab validation of wearables is needed (i.e. does a device show the same validity night after night) since wearables are intended for long-term monitoring of sleep. Finally, validation studies should consider the full range of measures potentially useful in research and/or clinical settings. For example, one measure rarely validated in either actigraphy or wearables is time-in-bed. Indeed, even actigraphy only automatically detects the “sleep interval” (i.e. the period between the first and last epoch of sleep) and requires user input to measure time-in-bed. Some commercial wearables also allow user input to specify time-in-bed. It would be extremely valuable, especially in disorders like insomnia, for technological developments and research to identify valid estimates of time-in-bed and to discriminate time-in-bed from pre-bedtime sedentary activities (e.g. watching TV in the dark or quietly reading) without the need for user input.

Workshop consensus opinion: guidelines for validation of wearables for sleep and circadian outcomes

When planning to conduct a validation study of a new wearable device, or an existing device in a new population, it is critical to use the following best practices to yield outcomes that are most useful for the sleep and circadian fields, and to allow comparisons across studies, devices, and algorithms. Initial validation studies should first assess the main device outcomes against the established sleep and circadian gold standards. Additional metrics such as those outlined in Tables 1 and 2 also require validation against the gold standards. Guidelines for conducting a rigorous validation study are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Guidelines for performing and interpreting results from device validation of sleep and circadian metrics

| Validation process | Practical recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Validation study implementation | ||

| Gold standard for comparison | • For total sleep time and sleep staging, PSG should be the only valid reference for wearable device validation. • When research-grade actigraphy is used in conjunction with a wearable device, both devices should be compared against PSG. • Portable full PSG systems can also be used for unattended PSG-device comparisons in at-home environments. • For circadian timing, 24 h profiles of core body temperature or dim light melatonin are the only valid references for wearable device validation. |

• Only PSG-device comparisons should be accepted for validation. • Manually score PSG sleep records using current AASM guidelines. • Perform double-scoring to minimize biases in PSG-device comparison. • 24 h assessments should be conducted in laboratory environments to control for confounding factors (e.g. posture, light, physical activity) |

| PSG-device synchronization | • Timing synchronization between PSG and devices is crucial, particularly for epoch-by-epoch analysis. | • Clearly report steps taken to ensure PSG-device synchronization. |

| Data access | • Device manufacturers as well as third-party research tools may provide access to epoch-by-epoch data and/or provide necessary support/information for device validation. | • As a minimum requirement for validation, access to key epoch-by-epoch sleep data should always be attempted and steps taken to obtain access should be clearly described • Information and known limitations on how a device defines and calculates key sleep or circadian metrics should be clearly described. |

| Device setting | • Wearable devices should be used and worn as per manufacturer instructions and specifications during validation. | • Sleep technicians or trained staff should apply the devices to the participants. • When algorithm sensitivity options are available ‘normal setting’ should be the first choice for comparing against the gold standard • If possible, the performance of different sensitivity settings should be also evaluated. |

| •Sample selection | • Dedicated independent validations specifically designed to test device performance under different populations and conditions are required elements of device validation. • Validations based on secondary aims and data collected as part of separate studies, i.e. ‘convenience samples’, are acceptable for preliminary studies, and must be reported as such in manuscripts. |

• Sample characteristics need to be fully described, including demographic and socioeconomic status. • Sample selection should be large enough to control or stratify by critical features (e.g. age, sex, sleep disorders) that potentially affect device performance. • When using convenience samples, there should, at minimum, be enough power to control for a variety of factors (e.g. age, and sex) |

| Step 2: Statistical analysis and reporting | ||

| Testing the significance of the device outputs versus the sleep and circadian gold standards | • It is important to directly compare the mean sleep or circadian metrics derived from the wearable device versus established gold standards utilizing basic mean comparison statistics such as t-tests, repeated measures ANOVA or linear mixed models (or equivalent non-parametric approaches). • This analysis will identify statistically significant systematic differences between the wearable device and gold standards and whether the device overestimates/underestimates specific outcomes, forming the basis for interpreting the biases from subsequent Bland-Altman analysis. |

• Provide a table with descriptive statistics for the gold standard parameters and the equivalent device sleep or circadian metrics, and their statistical differences (tests- and p-values). |

| Bland-Altman plots | • Bland–Altman plots qualitatively assess the concordance between two instruments and are ideal for evaluating overall device performance. • By plotting the gold standard values on the x-axis and the difference between the gold standard and device values (e.g. PSG TST - device TST) on the y-axis, the Bland-Altman plots allow visualization of the gold standard versus device discrepancies as a function of the gold standard measurements. |

• Bland-Altman plots and quantitative metrics such as mean differences (or biases), SD and ±95%CI of the biases, lower and upper limits of agreement for the gold standard versus device outcomes, should be provided. • For the interpretation, a significant direct comparison test and a positive bias indicates that the device underestimated the observed outcome, whereas a negative bias indicates that the device overestimated the observed outcome. • Proportional bias metrics provide information on the stability of differences between the gold standard and the device, and should be reported for each Bland-Altman plot. |

| Epoch-by-epoch (EBE) analysis | • EBE analysis allows the assessments of sensitivity (proportion of PSG epochs correctly identified as “sleep” by a wearable device) and specificity (proportion of PSG epochs correctly identified as “wake” by the device) of a device. • EBE should be performed on an individuals’ level. |

• Mean and SD of sensitivity and specificity should be provided. • Error matrix (or confusion matrix) providing the full representation of EBE analysis by cross tabulating the agreement and disagreement between device and PSG derived sleep outcomes should be included. • When device sleep staging is available, the “% of PSG-device agreement” in the EBE sleep classification (N1+N2 [considered “light sleep”], N3 [considered “deep sleep”] and REM sleep) should be provided. |

| Step 3: Important considerations when reporting validation study outcomes | ||

| Algorithm version and period for data collection | • A major concern in the use of consumer wearable devices is that proprietary algorithms used to process the device outcomes are subjected to frequent manufacturer updates. | • Provide date (beginning and end) of data collection, specific device model and firmware version. Avoid device updates during the data collection timeframe. When this is not possible, a statistical test of whether such updates affected performance is desirable. |

| Interpretation of study outcomes | • There is no current consensus on specific values or thresholds for considering the performance of a device as ‘good’, ‘bad’, or ‘acceptable’, and therefore these terms should be avoided when describing device performance. • The performance of a device should be judged based on the desired application and use (e.g. lower sensitivity/specificity may be acceptable in large population studies compared with smaller laboratory studies or clinical use in individual patients where the best possible device performance is desirable). |

• Outcomes (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, PSG-device discrepancies in TST) should be reported as they are. • There is not an ‘overall performance’ for a device. A device has distinct performances on distinct populations and outcomes. Subjective interpretation of study outcomes and direct comparison with previous validation studies in different populations or study conditions is potentially misleading and should be avoided. |

| Device malfunctioning | • The reliability of a device is an important aspect to consider. | • Number and reason of device failures should be reported. |

Despite the tendency to prioritize novelty in original manuscripts, validation studies should prioritize standardization and replication. Works from different groups replicating previous validations should be encouraged. Implementing a standardized typology (reflecting the requirements outlined in Table 3) would help facilitate consistency across validation studies. Once a device is validated against the gold standard for a specific population, follow-up studies should aim to replicate and extend the initial validation findings by also using the device to address a scientific question. For example, studies showing the applied or clinical utility of a device outside the laboratory are critical to show how useful the devices are in more naturalistic settings. Such studies might want to: (1) compare devices against actigraphy outside the lab (where actigraphy is an accepted methodology); (2) assess the concordance between measures of sleep or circadian rhythms from the device and clinical measures (e.g. symptom severity) or applied measures (e.g. performance); (3) test the ability of device measurements to predict changes in clinical or applied outcomes; and/or (4) test the utility of device measurements within already established prediction models (e.g. models of sleepiness and PVT performance currently utilized in operational settings). Studies testing the usefulness of consumer wearables in these contexts would likely have larger scientific and practical impacts than the original lab-based validation studies.

A public database containing the necessary meta-data (e.g. demographic and health status), results, and raw data of validation studies could encourage the dissemination of findings that simply replicate previous validation studies, and enhance the ability of researchers and clinicians to have quick access to validation data. For example, validation data that is part of a larger scientific study could be uploaded onto such a public database where it is easily accessed, instead of buried in supplementary files or not published. Furthermore, such a public database should include standardized wearable datasets that are matched with PSG data collected simultaneously with the wearable. This will allow engineers to rapidly improve product development and algorithms. This type data repository could also facilitate validation of algorithms rather than specific devices per se, and thereby create the opportunity to apply validated algorithms to multiple wearables.

Finally, the field must acknowledge the bias some hold against the use of consumer wearables in research. Such bias has led to a focus on the limitation of wearables, as well as to holding research with wearables to a different standard than the one used for actigraphy. Perhaps the most commonly expressed concern relates to the “black box” nature of algorithms used to analyze data from wearables. The common argument states in-lab validation studies only apply to the specific device model and firmware/software version used in a given study. Since the manufacturer can update firmware/software at any time, any other version of firmware/software must be considered suspect until validated. While this black box nature of consumer devices is a legitimate concern, it must be considered in a broader context. For example, actigraphy manufacturers also use proprietary algorithms that can change with any new version of software. This is why it is common practice to report the version of software utilized for a given study. The same should be true for studies employing consumer wearables (see Table 3). In addition, if firmware/software versions are tracked throughout a study, specific analyses can examine if such changes impacted validity or other outcome variables reported. One big difference between actigraphy and consumer wearables related to this concern is research grade actigraphy generally allows raw data access. Thus, if a user does not like or trust the proprietary algorithm, they are free to develop and validate their own, or to incorporate the raw data into other models. As stated below, we urge consumer wearable manufacturers to provide the same access to raw data, and some do. Implicit in the black box critique is the concern that device manufacturers will alter the algorithm for converting raw data (movement, heart-rate variability, etc.) into sleep/wake or sleep stage data when they update firmware/software. Yet, the field has long assumed actigraphy manufacturers do not alter their algorithms once independently validated. This implied trust manifests in a lack of validation studies examining the latest models/algorithms produced by the largest companies in the field. The inverse lack of trust in consumer manufacturers reinforces the black box concerns. Here, the onus is on investigators and reviewers to recognize (and perhaps question the validity of) this bias and on consumer manufacturers to increase trust by reporting when firmware/software changes affect the main outcome measures of their devices.

Workshop consensus opinion: considerations for using wearables in clinical and research settings

It is the committee’s position within the current scenario that the use of consumer wearables in sleep and circadian research and clinical sleep medicine is premature and must be carefully evaluated case-by-case. There is currently not enough evidence to support the accuracy/validity of multisensor sleep trackers in staging sleep, and to our knowledge, there is not a direct comparison between new (multisensor) and old (accelerometer-based) generation devices. Also, wearable devices should be considered in the measurement of night-time sleep only; the few studies assessing the accuracy of wearables for recording daytime naps showed strong limitations of these devices in automatic daytime sleep measurement [81, 84].

Despite the identified limitations, implementation of consumer-grade devices in sleep and circadian research and medical fields is already happening, reflecting an ongoing inevitable change within the sleep and circadian fields. With the idea that this process requires regulation, the committee proposes guidelines for using consumer wearables in clinical and research settings (Table 4). Overall, choice of a device should prioritize a high level of accuracy (as validated against gold standards), reliability, and usability. In addition to the following guidelines, note that the American Academy of Sleep Medicine published a position statement on the use of consumer wearable technologies to enhance the patient–clinician interaction in clinical settings [83].

Table 4.

Guidelines for how to choose a wearable device for research/clinical use

| Decision process | Practical recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

|

Step 1: Things to know before deciding to use a consumer wearable

Be aware of the limitations of using a consumer wearable device |

||

| Device types | • There are two main classes of wearable devices: (1) accelerometry-based and (2) multisensory sleep trackers. • The performance of accelerometry-based devices is currently more comprehensively characterized and understood compared to multisensory devices. • However, the capability of providing sleep/wake states, sleep stages, and sleep-related physiology is likely only possible using a multisensory device. |

• If only information about sleep/wake state is needed, accelerometry-based wearables may be suitable. • Only multisensory approaches offer a broader range of sleep (e.g. sleep staging) and sleep-related (e.g. heart rate) outcomes. • The new generation of multisensory wearables seem to generally perform better than motion based sensors in sleep/wake assessment. However, no direct comparisons are currently available. |

| Unregulated | • Currently, wearable technology is largely an unregulated space and consumer wearables are not designed for research and clinical purposes. | • This issue cannot be easily solved. Only devices with documented independent validation should be considered. |

| Proprietary algorithms and firmware updates | • The analytics and algorithms used to provide sleep and circadian metrics are unknown and likely to change over time (e.g. firmware updates). • Firmware updates may affect data acquisition over long-time, and thus the main outcomes (e.g. total sleep time) of interest. |

• All updates should be avoided during the data collection timeframe. • Firmware version should be recorded at the beginning and at the end of data acquisition, and at regular intervals during data acquisition. • If update is unavoidable, this should be used as a factor in the analysis. |

| Sleep and circadian metrics | • Definition of device outcomes may not be consistent with the scientific terminology. | • Only main sleep and circadian metrics clearly defined and specified by the device manufacturers should be used. • If there is uncertainty regarding sleep or circadian metrics from a device, it is recommended to clarify with the manufacturer For an example, the use of ‘deep sleep’ is acceptable only if specified as PSG N3 equivalence. |

| Data access | • Due to their proprietary nature, raw data (sensor data) for most consumer wearables are not accessible. | • Making raw data publicly available or accessible to researchers and clinicians whenever possible will enhance the rate of progress. • Data can sometimes be accessed directly by manufacturers’ web platforms, third party services, dedicated API. • The process to access data in validation studies should be reported |

| Understanding wearable validations | • Few device models are currently validated, and the only acceptable validations are those using established gold standards for comparison. • There is currently no consensus on interpreting validation study outcomes. |

• Validation results cannot be generalized to a brand or different populations • Results from wearable validation are only applicable to a specific device model, condition and sample tested. |

| Device malfunctioning or inappropriate use | High rate of devices failure (frequently above 15%) has been repeatedly reported. | • Available information on failure rates should be taken into account when deciding on a device for validation and research use • It is recommended to develop clear standard operating procedures and training of research staff on the use, application and troubleshooting of a device to minimize the risk of device malfunctioning and data loss • Trained staff should always set-up the wearable device on the participant using manufacturer specifications |

|

Step 2: Decision process: Study-specific factors to consider in choosing a device

Defining aims, sample, experimental design, and expected outcomes is a necessary step to inform the choice of a wearable. These factors can affect device performance, and thus study outcomes. |

||

| Sample | • Age, sex, presence of sleep disturbances, and other demographic factors may affect the accuracy of a device, and this impact may vary across different sleep outcomes. For an example, the accuracy of a device may be better/worse in young vs old adults in regards to total sleep time, but age may not be as important for heart rate. |

• The impact of demographic factors needs to be taken into account when interpreting wearable sleep data as differences in sleep outcomes (e.g. WASO) between young and old participants may be driven by differences in sensitivity/specificity and accuracy of the device across age. |

| Experimental design | • Experimental manipulations (e.g. sleep deprivation, circadian misalignment, drug trials) may affect device performance due to the dependency of device accuracy on features that will change as a result of the manipulation (e.g. accelerometer, heart rate and its variability, temperature) used by these devices. | • Planned between- and within-group comparisons testing the effect of experimental manipulations or conditions on device outcomes should be carefully interpreted. For an example, some data indicates device performance decreases with sleep restriction/deprivation. • Carefully check device manufacturers’ specification for any potential restriction in the use of a device. For an example some devices do not provide sleep information below a certain amount of time spent ‘asleep’. |

| Sleep, circadian, and other metrics of interest | • Each specific device has a distinct accuracy for each of the outcomes provided. | • Researchers/clinicians should evaluate a device based on the performance of the main variable of interest against PSG. For example, if interested in the amount of wakefulness at night, a device should be selected by prioritizing the device performance on PSG WASO estimation in validation studies. • Currently, only the main sleep outcomes should be considered for use (total sleep time, wake after the sleep onset, sleep onset and wake-up timing). |

| Day-time sleep | • The current evidence does not support the use of consumer wearable devices for daytime sleep assessment. | • Current wearable devices should not be used to assess daytime sleep or naps |

| Step 3: Interpretation of study outcomes based on consumer wearable data | ||

| Expected outcomes and magnitude of the effect | • Effect size is particularly important in the interpretation of the statistical or clinical significance in sleep and circadian metrics. • The effect size expected by researchers/clinicians in a particular comparison or trial may help inform the choice of a specific device. |

Researchers/clinicians should consider the magnitude of the expected effect size. |

The committee considered the idea of “how good is good enough” with respect to validation. It is likely the answer to this question is context dependent (e.g. general consumer use to track sleep, inclusion into research studies, screening, or diagnosis in clinical setting, etc). Furthermore, since device and algorithm validation will inevitably be an ongoing process as technology develops, the committee decided it was beyond the scope of this initial report to identify minimum validation requirements. However, the committee strongly encourages validation when implementing wearables for research use. Peer-reviewed sleep and circadian journals could consider requiring prior or concurrently published validation data, against the gold standards, for acceptance of any manuscripts describing scientific findings based on wearable technologies. When the paper under consideration uses a population different than that used in validation studies, limitations related to that difference should be discussed. As the number of validation studies grow and report different populations and different contexts, the strengths and weaknesses of each device will become more evident, similar to the evolution of the actigraphy literature.

Workshop consensus opinion: recommendations for industry on future directions to improve use, research access, and user transparency

As the use of sleep and circadian wearables by researchers and clinicians rises, there is an increasing need for engagement with industry toward developing standards and guidelines that facilitate research and clinical use of consumer wearables. This is particularly the case when public messaging and education around sleep and circadian health, directly by industry or by the media, are based on big data from wearable sleep and circadian devices. Big data has not only great research potential but also has risks of misinforming the public and biasing perceptions regarding sleep and circadian health if the data are derived from devices with limited validation and known or unpredictable inaccuracies. Such potential misuse of wearables could delay or even reverse the progress of the fields. There would seem to be a level of responsibility, beyond profit margins, for collaboration among industry stakeholders and academic scientists to: (1) ensure the data obtained from their products has demonstrated validity; (2) facilitate raw data access for research use; (3) set mutually agreed and standardized terminology of sleep and circadian metrics; and (4) exercise caution and inform the general public of limitations in the use and interpretation of non-peer-reviewed wearable data. At the same time, researchers and clinicians need to appreciate the concerns from industry around return on investment and intellectual property. The goals of scientists/clinicians and industry are equally valid and they will, at times, oppose one another. In the end, the consumer will benefit if all stakeholders can agree on ways to balance these concerns.

Future Directions and Needs of the Sleep and Circadian Fields

Interest in developing biomarkers of sleep and circadian health is rapidly expanding and has implications from basic research to clinical practice. Initial biomarker discovery efforts using controlled laboratory trials are underway [85–87]. As these efforts progress, we must expand beyond the laboratory setting and translate biomarkers into “real-world” settings using large-scale field studies and clinical trials. Such large-scale translational studies are not possible using the traditional gold standard sleep and circadian protocols. Wearable technologies, however, are ripe for such biomarker development and large-scale studies, consisting of data from up to millions of nights of sleep from commercial wearables. If successful, such biomarkers will create unprecedented opportunities to track changes in multisystemic physiological functions (e.g. heart rate, body temperature, respiration), behavioral and psychomotor outputs (e.g. general physical activity levels, specific movements, reaction times), and environmental factors (e.g. light, ambient temperature, geographical location) across different sleep and wake states, as well as across the 24-hour cycle. The success of such multisystemic data collection will rely on validation and standardization of wearable use. Altogether, the expansion and use of wearable technologies is squarely positioned in several aspects of the ongoing research agenda in the sleep and circadian fields [88].

One key area that wearables have potential to advance the field is in the assessment of fitness for duty, with implications for military organizations, first responders, health-care providers, and transportation industries. The adverse impacts of sleep loss and circadian misalignment on workplace safety and performance are increasingly recognized. This is especially relevant for individuals: (1) working extended hours, overnight, and/or frequently changing time zones and (2) whose tasks involve high risks for consequential errors or injuries to self or to others. Further work is required to determine how wearables may assist in quantifying not only previous sleep history but also integrate circadian timing with sleep history to quantify the levels of alertness required to safely perform duties. From this perspective, wearables have high potential to facilitate objective and independent monitoring to inform occupational health and safety policies and verify their implementation.

We anticipate that wearables will expand investigations of how sleep and circadian timing relate to transitions between wellness and disease states. This area of research has been mostly limited to objective data collected in relatively small laboratory studies, or to larger data sets based on self-reported subjective information. Wearables have the potential to facilitate collecting objective sleep and circadian data in large-scale longitudinal cohorts. There will notably be a need to link wearable data to other biomarkers such as omics, cardiometabolic, and endocrine markers, as well as clinical outcomes documented in electronic medical records. Wearables represent an invaluable tool to quantify the temporal dynamics of sleep and circadian biomarkers along the course of illnesses, a necessary step to better delineate the potential influence of sleep and circadian timing for health and disease. This is also crucial to explore the potential of sleep and circadian biomarkers to predict the emergence of illness and subsequent health trajectories. This may enable the development of objective self-monitoring systems with implications for personalized and preventative medicine and daily disease management.

Another promising research area is the potential use of wearables to track adherence to and changes following research or clinical interventions. Tracking how sleep or circadian metrics respond to specific interventions may unveil new indices of treatment response. This area of research has high potential to facilitate the translation of findings from laboratory-controlled studies to larger populations in prospective studies, and to translate research findings into clinical practice. In line with this concept, another opportunity for the sleep and circadian fields is to promote the use of validated wearables to track sleep and circadian physiology in related but independent fields of study. For example, using wearables to track sleep and circadian physiology in clinical trials focused on diabetes outcomes has high potential to advance the diabetes and the sleep and circadian fields.

With the near ubiquitous use of wearables in modern society, the data and user information associated with wearables represent potential ethical issues related to privacy and security. The potential of linking wearable data with electronic medical records further increases this concern. As the field progresses, standards and recommendations on security and privacy for consumers, researchers, and wearable companies will help mitigate this threat. Related, wearable device data could be used by employers and insurance companies to make decisions regarding hiring, promotion, and insurance premiums. Thus, access and use of wearable data must be controlled and regulated to ensure fair and equitable decision making in such scenarios.

There are potential economic conflicts of interest surrounding the use of wearables to diagnose disease. For example, if a wearable is used to diagnose a medical condition, the diagnostic thresholds will have a large impact on the number of individuals eligible for treatment. Medical care systems, insurance companies, wearable companies, pharmaceutical companies, health-care providers, researchers, and consumers all have unequal stakes in the economic and health outcomes associated with such diagnostic thresholds. Where possible, the sleep and circadian fields should help guide such decision making based on objective rigorous data. Ultimately, sleep and circadian scientists need to engage the general public and policy makers on best recommendations and practices for the use of sleep and circadian wearables, especially as the data relates to the health and well-being of the public.

Conclusion

Given the advancements in the sleep and circadian fields in recent decades, the development of validated sleep and circadian biomarkers has great potential to enhance the translation of basic sleep and circadian research into clinical practice [35]. As a field, we are in the early biomarker development phase, and it is important to explore all potential biomarker development pipelines, including the use of wearable technology. As various biomarker development approaches are explored, the field should consider the use of different technologies to develop different biomarkers where appropriate (e.g. acute versus chronic insufficient sleep). Furthermore, continued collaboration in biomarker development efforts across labs, between the sleep and circadian fields, and in conjunction with industry and clinical efforts will have the highest probability of success.

The 2018 “International Biomarkers Workshop on Wearables in Sleep and Circadian Science” characterized the use of “wearable” to include wearables, nearables, and ingestibles. The committee identified the poor validation of current wearables as the primary barrier in applying wearables to sleep and circadian research on a large scale. As such, the committee defined the best practices for validation studies (Table 3) and provided guidelines for selecting wearables in future research (Table 4). As the field progresses, it is essential for new biomarkers to maintain the established level of rigor and reproducibility that exists in the current gold standards. Collectively, the sleep and circadian fields must uphold these standards, especially as the use of wearable devices to quantify sleep and circadian metrics expands into other fields of research. Finally, the committee identified key future directions and needs of the sleep and circadian fields in the biomarker space. In general, there is a large need to translate findings from laboratory studies into large-scale field studies and clinical trials and we support the continued development and validation of wearable devices and technology to support such large-scale trials and advance the fields.

Acknowledgments

The Sleep Research Society and notably the Board of Directors of the Sleep Research Society are acknowledged for supporting the workshop on which this white paper is based. Participants of the workshop included members of the Sleep Research Society, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Asian Society of Sleep Medicine, Australasian Sleep Association, Canadian Sleep and Circadian Network, Canadian Sleep Society, Canadian Society for Chronobiology, Cerebra, Department of Defense of the United States of America, European Sleep Research Society, f.Lux, National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States of America, National Institutes of Health of the United States of America, National Center for Sleep Disorders Research of the United States of America, Rythm, and Society for Research on Biological Rhythms. On behalf of all workshop participants, each coauthor contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and has approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement. S.P.A.D. serves on the DSMB for an insomnia trial sponsored by Zelda Therapeutics and consults for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Neither effort is related to this manuscript. M.Z. has received research funding unrelated to this work from Ebb Therapeutics Inc., Fitbit Inc., International Flavors & Fragrances Inc., and Noctrix Health, Inc. and is an advisor at Snooze, LLC. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Watson NF, et al. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1161–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watson NF, et al.. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual (3rd ed) (ICSD-3). Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effect of short sleep duration on daily activities—United States, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(8):239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Short Sleep Duration Among US Adults 2014; https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html. Accessed 24 September 2018.

- 6. Ford ES, et al. Trends in self-reported sleep duration among US Adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep. 2015;38(5):829–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mysliwiec V, et al.. Sleep disorders and associated medical comorbidities in active duty military personnel. Sleep. 2013;36(2):167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Depner CM, et al.. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(7):507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. St-Onge MP, et al.. Sleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(18):e367–e386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Depner CM, et al. Ad libitum weekend recovery sleep fails to prevent metabolic dysregulation during a repeating pattern of insufficient sleep and weekend recovery sleep. Curr Biol. 2019;29(6):957–967 e954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cappuccio FP, et al.. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(12):1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cappuccio FP, et al.. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cappuccio FP, et al.. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31(5):619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colten HRAB, eds. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vgontzas AN, et al.. Adverse effects of modest sleep restriction on sleepiness, performance, and inflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(5):2119–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. John U, et al.. Relationships of psychiatric disorders with sleep duration in an adult general population sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39(6):577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dinges DF, et al.. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20(4):267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carskadon MA, et al.. Cumulative effects of sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness. Psychophysiology. 1981;18(2):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barger LK, et al.; Harvard Work Hours, Health, and Safety Group Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(2):125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Åkerstedt T, et al. Accidents and Sleepiness: a consensus statement from the International Conference on Work Hours, Sleep and Accidents, Stockholm, 8-10. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:195. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lucey BP, et al.. How amyloid, sleep and memory connect. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(7):933–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bokenberger K, et al.. Association between sleep characteristics and incident dementia accounting for baseline cognitive status: a prospective population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(1):134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cappuccio FP, et al.. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gallicchio L, et al.. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(2):148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Decker MJ, et al.. Hypersomnolence and sleep-related complaints in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(4):435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson DA, et al. Undiagnosed sleep disorders in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A2926. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kubo T. [Estimate of the number of night shift workers in Japan]. J UOEH. 2014;36(4):273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wickwire EM, et al.. Shift work and shift work sleep disorder: clinical and organizational perspectives. Chest. 2017;151(5):1156–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright KP Jr, et al.. Shift work and the assessment and management of shift work disorder (SWD). Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wittmann M, et al.. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1-2):497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roenneberg T, et al.. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol. 2012;22(10):939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baron KG, et al.. Circadian misalignment and health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):139–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith MR, et al.. Shift work: health, performance and safety problems, traditional countermeasures, and innovative management strategies to reduce circadian misalignment. Nat Sci Sleep. 2012;4:111–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roenneberg T, et al.. The circadian clock and human health. Curr Biol. 2016;26(10):R432–R443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mullington JM, et al.. Developing biomarker arrays predicting sleep and circadian-coupled risks to health. Sleep. 2016;39(4):727–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moar J. Where Now for Wearables.2018; https://www.juniperresearch.com/document-library/white-papers/where-now-for-wearables. Accessed 5/20/2019, 2019.

- 37. Webster JB, et al.. An activity-based sleep monitor system for ambulatory use. Sleep. 1982;5(4):389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ancoli-Israel S, et al.. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26(3):342–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Littner M, et al. Practice parameters for the role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms: an update for 2002. Sleep. 2003;26(3):337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morgenthaler T, et al.. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep. 2007;30(4):519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. American Sleep Disorders Association. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the clinical assessment of sleep disorders. Sleep. 1995;18(4):285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rechtschaffen AKA. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malhotra A, et al.. Performance of an automated polysomnography scoring system versus computer-assisted manual scoring. Sleep. 2013;36(4):573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Broussard JL, et al. Circadian rhythms versus daily patterns in human physiology and behavior. In: Kumar V, ed. Biological Timekeeping: Clocks, Rhythms and Behaviour. New Delhi: Springer India; 2017:279–295. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Duffy JF, et al.. Getting through to circadian oscillators: why use constant routines? J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17(1):4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burgess HJ, et al.. Home circadian phase assessments with measures of compliance yield accurate dim light melatonin onsets. Sleep. 2015;38(6):889–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37(1):9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berry RB, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications Version 2.5. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Darien , IL: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Massimini M, et al.. The sleep slow oscillation as a traveling wave. J Neurosci. 2004;24(31):6862–6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93(5):1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(3):354–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lucas RJ, et al.. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gruwez A, et al.. Reliability of commercially available sleep and activity trackers with manual switch-to-sleep mode activation in free-living healthy individuals. Int J Med Inform. 2017;102:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. O’Driscoll DM, et al.. Energy expenditure in obstructive sleep apnea: validation of a multiple physiological sensor for determination of sleep and wake. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(1):139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Zambotti M, et al. Wearable sleep technology in clinical and research settings. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51( 7):1538–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dittmar A, et al.. A non invasive wearable sensor for the measurement of brain temperature. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;1:900–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gunga HC, et al.. The Double Sensor-A non-invasive device to continuously monitor core temperature in humans on earth and in space. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;169(Suppl 1):S63–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang M, et al.. A wearable thermometry for core body temperature measurement and its experimental verification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2017;21(3):708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chételat O, et al.. Clinical validation of LTMS-S: A wearable system for vital signs monitoring. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:3125–3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hasselberg MJ, et al.. The validity, reliability, and utility of the iButton® for measurement of body temperature circadian rhythms in sleep/wake research. Sleep Med. 2013;14(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Darwent D, et al.. The validity of temperature-sensitive ingestible capsules for measuring core body temperature in laboratory protocols. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(8):719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Monnard CR, et al.. Issues in continuous 24-h core body temperature monitoring in humans using an ingestible capsule telemetric sensor. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Woelders T, et al.. Daily light exposure patterns reveal phase and period of the human circadian clock. J Biol Rhythms. 2017;32(3):274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cheng WO, et al. Using mathematical modeling to predict circadian phase in night shift workers. Sleep. 2018;41:A237–A237. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stone JE, et al.. Temporal dynamics of circadian phase shifting response to consecutive night shifts in healthcare workers: role of light-dark exposure. J Physiol. 2018;596(12):2381–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Baron KG, et al.. Feeling validated yet? A scoping review of the use of consumer-targeted wearable and mobile technology to measure and improve sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. de Zambotti M, et al. The sleep of the ring: comparison of the OURA sleep tracker against polysomnography. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17( 2):124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pesonen AK, et al.. The validity of a new consumer-targeted wrist device in sleep measurement: an overnight comparison against polysomnography in children and adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(4):585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. MAC. LZM. Validity of consumer activity wristbands and wearable EEG for measuring overall sleep parameters and sleep structure in free-living conditions. J Healthc Inform Res. 2018;2:152–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Toon E, et al.. Comparison of commercial wrist-based and smartphone accelerometers, actigraphy, and PSG in a clinical cohort of children and adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(3):343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Montgomery-Downs HE, et al.. Movement toward a novel activity monitoring device. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(3):913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Meltzer LJ, et al.. Comparison of a commercial accelerometer with polysomnography and actigraphy in children and adolescents. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. de Zambotti M, et al.. Validation of sleep-tracking technology compared with polysomnography in adolescents. Sleep. 2015;38(9):1461–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. de Zambotti M, et al.. Evaluation of a consumer fitness-tracking device to assess sleep in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32(7):1024–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mantua J, et al. Reliability of sleep measures from four personal health monitoring devices compared to research-based actigraphy and polysomnography. Sensors. 2016;16(5): 646–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. de Zambotti M, et al.. Measures of sleep and cardiac functioning during sleep using a multi-sensory commercially-available wristband in adolescents. Physiol Behav. 2016;158:143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cook JD, et al.. Utility of the Fitbit Flex to evaluate sleep in major depressive disorder: a comparison against polysomnography and wrist-worn actigraphy. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kang SG, et al.. Validity of a commercial wearable sleep tracker in adult insomnia disorder patients and good sleepers. J Psychosom Res. 2017;97:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Maskevich S, et al.. Pilot validation of ambulatory activity monitors for sleep measurement in Huntington’s disease gene carriers. J Huntingtons Dis. 2017;6(3):249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. de Zambotti M, et al.. A validation study of Fitbit Charge 2™ compared with polysomnography in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(4):465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Cook JD, et al.. Ability of the Fitbit Alta HR to quantify and classify sleep in patients with suspected central disorders of hypersomnolence: A comparison against polysomnography. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(4):e12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Paquet J, et al.. Wake detection capacity of actigraphy during sleep. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1362–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Khosla S, et al.. Consumer sleep technology: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):877–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sargent C, et al.. How well does a commercially available wearable device measure sleep in young athletes? Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(6):754–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Laing EE, et al. Identifying and validating blood mRNA biomarkers for acute and chronic insufficient sleep in humans: a machine learning approach. Sleep. 2019;42(1), zsy186. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Laing EE, et al. Blood transcriptome based biomarkers for human circadian phase. Elife. 2017;6:e20214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wittenbrink N, et al.. High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(9):3826–3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zee PC, et al.. Strategic opportunities in sleep and circadian research: report of the Joint Task Force of the Sleep Research Society and American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 2014;37(2):219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Cook JD, et al.. Ability of the multisensory jawbone UP3 to quantify and classify sleep in patients with suspected central disorders of hypersomnolence: a comparison against polysomnography and actigraphy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]