Abstract

Objectives

To compare physical activity (PA) and exercise dependence (ED) in 267 weight-loss-maintainers (WLM) and 213 normal-weight (NW) controls.

Methods

PA and ED assessed via accelerometery and the Exercise Dependence Questionnaire.

Results

WLM had higher PA levels and ED scores than NW (P< 0.0001). WLM status (P=.006) and higher PA (P=.0001) were independently related to higher ED, although effect sizes were larger for PA. Exercising for weight control was the ED domain that discriminated WLM from NW.

Conclusions

WLM have higher ED scores than NW, but this is mostly due to exercising for weight control.

Keywords: physical activity, exercise dependence, weight loss maintenance, accelerometry, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Successful weight loss maintainers engage in approximately 60–90 minutes of physical activity per day.1,2 Although habitual physical activity has many physical and psychological benefits, concerns have been raised as to whether maintaining this high level of physical activity in the long-term is related to an unhealthy preoccupation with exercise indicative of dependency.3

Exercise dependence is thought to involve tolerance, in which there is a need for higher amounts of exercise to achieve the desired effects, and withdrawal, characterized by negative affective and somatic states when exercise is discontinued.3–7 Other associated features may include limited control over exercise behavior,3–6 interference with social functioning,4–6 persistence in exercising despite medical contraindications,3,5,6 and exercising to avoid withdrawal symptoms and weight gain.3–11 ED has predominantly been studied in eating disordered populations and in young athletes and, in these populations, has been shown to be associated with higher dietary restraint, disinhibition, and body image concerns.10–17

However, no previous study has examined level of ED in successful weight loss maintainers, a population characterized by high levels of dietary restraint, weight-gain vigilance, and exercise participation. We recently reported that weight loss maintainers of normal body weight engage in higher levels of physical activity (58.6 vs 52.1 min/d), and more vigorous intensity activity in particular (24.4 vs 16.9 min/d) than normal-weight individuals who have no history of obesity.1 Whether weight loss maintainers also exhibit correspondingly higher symptoms of ED is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine symptoms of exercise dependence in a group of weight loss maintainers (WLM) and always normal-weight (NW) individuals. We hypothesized that WLM would report higher exercise dependence scores than NW, perhaps due to heightened concerns about weight gain and body shape,4, 6, 10 but would not reach the level of ED seen in clinical populations.

METHODS

Subjects and Procedures

Participants were in a cross-sectional comparison study examining weight control behaviors of successful long-term weight loss maintainers and normal weight controls (ie, the “LITE” study). Details of the study sample and methods have been reported elsewhere.1 A convenience sample of men and women was recruited through placement of an advertisement about the study in national and local publications intended for a general audience. Persons who were interested in participating were given the option of calling a toll-free number or to visit a website. Although participants were from locations across the United States, the majority were derived from New England, California and the Washington, DC area.

Study eligibility was determined via phone screen. Participants in the WLM group had to have been overweight or obese (BMI ≥25) in the past, but presently be normal weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9) having lost ≥10% of their lifetime maximum body weight. Furthermore, to identify the most successful weight loss maintainers, participants had to have kept off a loss of ≥10% for at least 5 years, and be weight stable (±10 lb) during the past 2 years. Participants in the NW group had to have a current BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 and no history of overweight or obesity. In addition, these participants had to be weight stable (±10 lb) for at least 2 years prior to enrollment. Of the 813 subjects who responded to advertisements and a brief online screening tool specifying these criteria, 528 were deemed eligible via phone screen. Of these, 480 signed consent forms and participated in the study assessments. Participant characteristics are in Table 1. Participants received a $50 honorarium for completing all study assessments. The study received approval from The Miriam Hospital Institutional Review Board, Providence RI, USA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Weight Loss Maintainer (WLM) and Normal-Weight (NW) Participants

| WLM (N = 267) | NW (N = 213) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.9 ± 12.4 | 46.7 ± 13.0 | 0.34 |

| % Female | 82.4 | 87.3 | 0.16 |

| % Caucasian | 95 | 93 | 0.34 |

| Current BMI (kg/m2) | 22.0 ± 2.0 | 21.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0001 |

| Lifetime maximum weight (kg) | 92.2 ± 18.2 | 62.0 ± 8.1 | 0.0001 |

| Weight loss from lifetime maximum (%) | 30.0 ± 14.4 | 3.7 ± 3.8 | 0.0001 |

| Duration of weight loss maintenance (years) | 13.5 ± 9.3 | ------ | |

| Physical activity minutes/day (METs ≥ 3) | 65.4 ± 39.6 | 55.3 ± 27.1 | .004 |

| Concerns about shape (EDE-Q) | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.0001 |

| Concerns about eating (EDE-Q) | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.0001 |

| Cognitive restraint (EI) | 14.7 ± 4.0 | 10.0 ± 5.0 | 0.0001 |

| Disinhibition (EI) | 4.9 ± 3.3 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 0.0001 |

Note.

kg= kilograms

Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire

EI= Eating Inventory

Measures

Demographics and weight

Participants reported information about gender, marital status, ethnicity/race, and education. Weight and weight history were based on self-report, which have been validated in previous research.18 Lifetime maximum weight was assessed by the question, “List the highest weight you have ever been, excluding pregnancy.”

Exercise dependence

The Exercise Dependence Questionnaire (EDQ)4 was used to assess symptoms of exercise dependence. This measure consists of 29 items and 8 subscales reflecting various attributes of exercise dependence. Individual items within each subscale are scored on a (1) “strongly disagree” to (7) “strongly agree” likert scale. These subscales and sample items include: Interference with social/family/work life (“My pattern of exercise interferes with my social life”); positive reward (“After an exercise session, I feel more positive about myself”); withdrawal symptoms (“If I cannot exercise, I feel agitated”); exercise for weight control (“I exercise to control my weight”); insight into problem (“I feel guilty about the amount I exercise”); exercise for social reasons (“I exercise to meet other people”); exercise for health reasons (“I exercise to feel fit”); and, stereotyped behavior (“I exercise for the same amount of time each week”). Internal reliabilities (α) for subscales range from 0.52 for stereotyped behavior to 0.81 for interference with social/family/work life. Total exercise dependence score (α = 0.84) reflecting overall level of exercise dependence is calculated by summing the scores on each of the 8 subscales. The EDQ has been shown to be valid in relation to self-reported exercise behavior, with higher number of weekly exercise hours being associated with higher scores on individual EDQ domains and total exercise EDQ score.4

Physical activity

Participants in both groups wore the RT3 triaxial accelerometer (Stayhealthy, Inc, Monrovia, CA). The RT3 has been shown to be reliable,19 a strong predictor of oxygen consumption,20 and more accurate than other accelerometers in estimating high-intensity activity.21 For RT3-generated data to be considered valid, a minimum of 4 days with at least 10 hours wear time each day was required. Based on participants’ age and previous recommendations,22–24 a metabolic equivalent (MET) level ≥3 was used to compute daily time (min/d) spent performing moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA). Also based on previous research,25 participants were categorized as “high exercisers” (≥ 60 MVPA min/d) and “low exercisers” (< 60 MVPA min/d).

Cognitive restraint and disinhibition

The Eating Inventory (EI), developed by Stunkard and Messick,26 was used to assess cognitive restraint (ie, conscious control over food intake) and disinhibition (ie, eating in response to emotional, cognitive, or social cues). In general, higher cognitive restraint scores and lower disinhibition are associated with greater weight control.27 The scale is widely used in obesity research and has documented reliability and validity.28

Eating and shape concerns

The Eating Concern and Shape Concern subscales of the Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (EDE–Q)29 were used to assess fear of weight regain and body image concerns. The EDE-Q is the self-report version of the investigator-based EDE interview.30 The Eating Concern subscale reflects the degree of concern with food, eating, and calories (eg, “have you spent much time between meals thinking about food?”). The Shape Concern subscales measure the degree of concern with shape and fear of weight gain (eg, “over the past few weeks have you been afraid that you might gain weight?”). Items are rated on 7-point forced-choice scales (0–6), with higher scores reflecting greater frequency.

Statistics

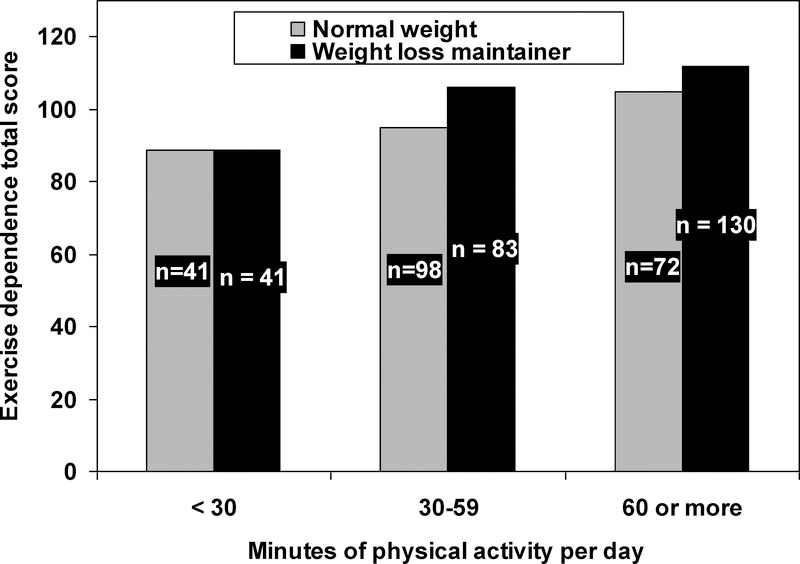

Descriptive statistics are presented in tables as either means ± SD for continuous measures or as percentages for categorical responses. Chi-square analyses or independent t-tests were conducted to assess differences between the groups on demographic variables. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine differences between the WLM and NW groups on total and individual Exercise Dependence Questionnaire (EDQ) domain scores, the EDE-Q shape and eating concerns subscale scores, and cognitive restraint scores, adjusting for BMI and physical activity. Linear regression was used to examine the effects of group status and physical activity on total ED score, adjusting for BMI. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify factors that independently discriminated WLM from NW. For Figure 1, we categorized exercise based on < 30, 30–59, and ≥ 60 MVPA minutes/day.

Figure 1.

Total exercise dependence scores and exercise duration in normal weight (NW) and weight loss maintainers (WLM).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and weight-related information for the weight loss maintainer (WLM) and normal-weight (NW) groups are presented in Table 1. Both groups were similar in age (46.7 ± 11.4 years), gender (85% female), and race/ethnicity (94% Caucasian). Both groups were normal weight, but WLM had slightly higher BMI (22.0 ± 2.0 vs. 21.2 ± 1.8 kg/m2; P=0.0001). WLM had significantly higher levels of restraint, disinhibition, and body and shape concerns than normal weight. Moreover, the WLM engaged in significantly more daily MVPA compared to NW (65.4 ± 39.6 vs. 55.3 ± 27.1 min/d; P=.004).

Total exercise dependence scores were higher in WLM than NW (P<0.0001). Similarly, total ED scores were higher in those who achieved more minutes per day of MVPA levels (r = .29; P=.0001). In regression analyses, both WLM status (P=.006) and higher levels of physical activity (P=.0001) were independently related to higher total ED scores, but the effect size estimates were larger for physical activity level than for group status (partial eta squared = .08 vs.03, respectively). Thus, although WLM reported higher exercise dependence scores than NW, the greatest difference was observed between high and low exercisers. As illustrated in Figure 1, ED scores were lowest in those who engaged in < 30 minutes per day of activity (and near identical between NW and WLM in this category of activity) and highest in those who engaged in >60 minutes per day.

Table 2 shows that the WLM group not only had significantly higher total exercise dependence, but also had somewhat higher scores on multiple individual exercise dependence domains, including interference with social/family/work, withdrawal symptoms, exercising for weight control, and stereotyped behavior (Ps<0.05). This effect was seen both with and without adjusting for physical activity. However, with the exception of withdrawal symptoms, scores in both groups were consistently lower than those of clinical populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exercise Dependence and Related Variables: Differences between Weight Loss Maintainer (WLM) and Normal Weight (NW) Groups and Clinical Eating-Disordered Samples

| WLM (n = 267) | NW (n = 213) | P* | Clinical Eating Disordered Samples§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise Dependence Questionnaire (EDQ) | ||||

| Total score | 106.3 ± 19.0 | 97.7 ±19.8 | 0.0001 | 135.2 |

| Interference with social/family/work | 10.7 ± 4.0 | 9.7 ± 3.6 | 0.04 | 19.8 |

| Positive reward | 21.6 ± 4.4 | 21.0 ± 4.8 | 0.39 | 23.7 |

| Withdrawal symptoms | 15.9 ± 5.7 | 14.3 ± 5.5 | 0.02 | 14.3 |

| Exercise for weight control | 17.7 ± 4.6 | 14.2 ± 4.8 | 0.0001 | 21.1 |

| Insight into problem | 6.1 ± 3.0 | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 0.11 | 9.3 |

| Exercise for social reasons | 5.8 ± 2.9 | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 0.77 | 10.3 |

| Exercise for health | 18.7 ± 3.2 | 18.1 ± 3.6 | 0.10 | 16.7 |

| Stereotyped behavior | 9.7 ± 3.2 | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 0.002 | 11.0 |

Note.

EDQ = Exercise Dependence Questionnaire

EDE-Q = Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire

EI = Eating Inventory

P values adjusted for BMI and total daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity minutes; means in the table are unadjusted for ease in interpretation.

Scores for clinical eating-disordered sample derived from Bamber et al.12

We next sought to determine which of the ED variables most strongly discriminated WLM from NW, independent of daily minutes of physical activity. After adjusting for physical activity and demographic variables (ie, BMI, gender, education, race, marital status), exercising for weight control was the only ED dimension that significantly discriminated between WLM from NW (OR = 1.2 [1.0–1.20]; P=.0001). Adjusting for restraint, disinhibition, and eating and shape concerns did little to alter these results (OR=1.2 [1.0–1.2]P=.05).

DISCUSSION

This study compared exercise dependence symptoms in long-term weight loss maintainers and normal weight individuals without a history of obesity. We found that weight loss maintainers scored significantly higher than normal weight controls on overall exercise dependence as well as many of the exercise dependence subscales. However, the exercise dependence variable that best discriminated weight loss maintainers from normal weight controls was their motivation to exercise for weight control. Thus, while weight loss maintainers may experience some symptoms of exercise dependence, what set them most apart from normal weight controls was their motivation for weight control, rather than the “unhealthy” aspects of exercise dependence.

The total level of exercise dependence observed in weight loss maintainers, although higher than normal weight, was substantially below the levels previously reported in clinical populations of patients with eating disorders.12 Weight loss maintainers scored lower than clinical populations on all the subscales with the exception of withdrawal symptoms, which includes feeling irritated and agitated when unable to exercise and “hating” not being able to exercise. These greater “withdrawal” feelings may relate to a fear or weight regain associated with inactivity or to the greater level of physical activity seen in weight loss maintainers. These feelings also may serve to motivate weight loss maintainers to continue to be active. However, future research is needed to determine the role of withdrawal symptoms in motivating healthy vs. unhealthy exercise behavior. Overall, weight loss maintainers appeared to exhibit only sub-clinical symptoms of exercise dependence.

Interestingly, level of physical activity was more strongly related to participants’ total exercise dependence score than was WLM status. Clearly, maintaining a high level of physical activity requires significant time commitment, which may affect time allocated toward work, social, and family life. Likewise, those who enjoy exercise the most may experience frustration when they are unable to adhere to their exercise plans or routine. Thus, higher scores on the ED scale may reflect a greater commitment to exercise per se and not necessarily the more negative connotations of “exercise dependence.”

Higher disinhibition and restraint also characterized weight loss maintainers relative to NW. The weight loss maintainers’ greater dietary restraint, as well as motivation to exercise for weight control and stricter exercise routine, fits well within a general pattern of controlled behavior seen in this population. Observational and experimental research shows that in addition to habitual performance of high levels of activity, individuals who are most successful at maintaining their weight loss report strict adherence to a behavioral routine that involves frequent self-weighing, counting calories, eating regular small meals, and avoidance of situations and times that stimulate overeating.32–34 Although WLM had higher disinhibition scores than NW, their scores overall were low, particularly as compared with clinical eating disorder populations (ie, 5 vs. 12, respectively).35,36

This study is the first to examine symptoms of exercise dependence in a weight loss maintainer group and a healthy normal weight control group; the study used a continuum measure of exercise dependence and an objective measure of physical activity. Moreover, while most previous studies have assessed exercise dependence in young adults, this study examined exercise dependence in an adult population. However, the study also has some limitations. The sample was self-selected and predominately female. The majority of study participants were also Caucasian. Whether findings would generalize to more ethnically diverse populations remains unclear. Moreover, the study used a cross-sectional design. Future prospective weight loss trials are needed that incorporate measures of exercise dependence to assess whether post-treatment increases in such symptoms occur and whether these increases are associated with greater changes in diet, exercise and weight loss and maintenance. Finally, this study did not measure metabolic or genetic factors that might underlie the observed differences in exercise dependence scores. Lower metabolic rates have been observed in previously obese individuals relative to controls,37 and a lower metabolic rate in weight loss maintainers could necessitate more physical activity to maintain a given body weight and could also affect ED scores. However, our previous work found no significant differences in resting metabolic rates between long-term weight loss maintainers and normal weight controls.38

In conclusion, this study suggests that higher exercise levels are significantly associated with exercise dependence, but being a weight loss maintainer also increases exercise dependence. The exercise dependence variable that best discriminated weight loss maintainers from their normal weight counterparts was higher motivation to exercise for weight control, rather than any of the unhealthy aspects of exercise dependence. Future clinical trial research is needed to determine the impact of weight loss interventions on exercise dependence symptoms, including withdrawal and motivation for weight control, and whether these symptoms complicate or ultimately help efforts at long-term weight control.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK066787. A portion of these data were presented in abstract form at the 2008 annual scientific meeting of The Obesity Society.

Contributor Information

Suzanne Phelan, Associate Professor, Department of Kinesiology, California Polytechnic State University; 1 Grand Avenue, San Luis Obispo, CA 93407-0386.

Dale S. Bond, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University/The Miriam Hospital, 196 Richmond Street; Providence RI 02906.

Wei Lang, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University Health Sciences; 1 Technology Place, Medical Center Blvd., Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 27157-1063.

Dustin Jordan, Research Associate, University of Auckland School of Population Health, Gate 1 Tamaki Campus, 261 Morrin Rd; Auckland, New Zealand.

Rena R. Wing, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University/The Miriam Hospital, 196 Richmond Street; Providence RI 02906.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phelan S, Roberts M, Lang W, et al. Empirical evaluation of physical activity recommendations for weight control in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(10):1832–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catenacci VA, Ogden LG, Stuht J, et al. Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(1):153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veale DM. Exercise dependence. Br J Addict. 1987;82(7):735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden J, Veale D, Summers Z. The development and validation of the exercise dependence questionnaire. Addict Res Theory. 1997;5(4):343–356. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hausenblas HA, Symons Downs D. Exercise dependence: a systematic review. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2002;3(2):89–123. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamber DJ, Cockerill IM, Rodgers S, et al. Diagnostic criteria for exercise dependence in women. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(5):393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamer M, Karageorghis CI. Psychobiological mechanisms of exercise dependence. Sports Med. 2007;37(6):477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yates A, Shisslak CM, Allender J, et al. Comparing obligatory to nonobligatory runners. Psychosomatics. 1992;33(2):180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis C, Brewer H, Ratusny D. Behavioral frequency and psychological commitment: necessary concepts in the study of excessive exercising. J Behav Med. 1993;16(6):611–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbourne KE, Chen J. The continuum model of obligatory exercise: a preliminary investigation. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mond J, Myers TC, Crosby R, et al. ‘Excessive exercise’ and eating-disordered behavior in young adult women: further evidence from a primary care sample. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16(3):215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bamber D, Cockerill IM, Carroll D. The pathological status of exercise dependence. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(2):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaren L, Gauvin L, White D. The role of perfectionism and excessive commitment to exercise in explaining dietary restraint. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29(3):307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, et al. Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006:39(6):454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu H, Bushman BA, Woodard RJ. Social physique anxiety, obligation to exercise, and exercise choices among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Marchesini G. Compulsive exercise to control shape or weight in eating disorders: prevalence, associated features, and treatment outcome. Comp Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):346–352. ???This only has 2 authors then et al, it should have 3 before et al.??? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bratland-Sanda S, Sundgot-Borgen J, Rø O, et al. Physical activity and exercise dependence during inpatient treatment of longstanding eating disorders: an exploratory study of excessive and non-excessive exercisers. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(3):266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, et al. What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(2):177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell SMP, Rowland AV. Inter-monitor variability of the RT3 accelerometer during a variety of physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36(2):324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowlands AV, Thomas PWM, Eston RG, et al. Validation of the RT3 triaxial accelerometer for the assessment of physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(3):518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowlands AV, Stone MR, Eston RG. Influence of speed and step frequency during walking and running on motion sensor output. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(4):716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity Promoting physical activity: a guide for community action. 1999; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Services USDHS. Physical Activity and Health: A report of the Surgeon General. 1996; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1081–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 6th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. Eating Inventory Manual. 1988; Harcourt Brack Jovanovich: San Antonio. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Swain RM, et al. The Eating Inventory in obese women: clinical correlates and relationship to weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Dis. 1998;22(8):778–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination (12th edition). In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment. Guilford Press: New York, 1993, pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phelan S, Wing RR, Raynor HA, et al. Holiday weight management by successful weight losers and normal weight individuals. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(3):442–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, et al. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(12):3091–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wing RR, Papandonatos G, Faval JL, et al. Maintaining large weight losses: the role of behavioral and psychological factors. J Consult Clin Psych. 2008;76:1015–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bond DS, Phelan S, Leahey T, et al. Weight loss maintenance in successful weight losers: surgical versus non-surgical methods. Int J Obes. 2009;33(1):173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Passi VA, Bryson SW, Lock J. Assessment of eating disorders in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: self-report questionnaire versus interview. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33(1):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Brandl B. Recurrent overeating: an empirical comparison of binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Astrup A, Gotzsche PC, van de Werken, et al. Meta-analysis of resting metabolic rate in formerly obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69(6):1117–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyatt HR, Grunwald GK, Seagle HM, et al. Resting energy expenditure in reduced-obese subjects in the National Weight Control Registry. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69(6):1189–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]