Abstract

Introduction

Social isolation and loneliness are positively associated with metabolic syndrome. However, the mechanisms by which social isolation affects metabolic syndrome are not well understood.

Research design and methods

This study was designed as a cross-sectional study of baseline results from the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center (CMERC) Cohort. We included 10 103 participants (8097 community-based low-risk participants, 2006 hospital-based high-risk participants) from the CMERC Cohort. Participants aged 65 years or older were excluded. Multiple imputation by chained equations was applied to impute missing variables. The quantitative properties of social networks were assessed by measuring the ‘size of social networks’; qualitative properties were assessed by measuring the ‘social network closeness’. Metabolic syndrome was defined based on the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess association between social network properties and metabolic syndrome. The mediating effects of physical inactiveness, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms were estimated. Age-specific effect sizes were estimated for each subgroup.

Results

A smaller social network was positively associated with higher prevalences of metabolic syndrome in all subgroups, except the high-risk male subgroup. There was no clear association between social network closeness and metabolic syndrome. In community-based participants, an indirect effect through physical activity was detected in both sexes; however, in hospital-based participants, no indirect effects were detected. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and depression did not mediate the association. Age-specific estimates showed that the indirect effect through physical activity had a greater impact in older participants.

Conclusions

A smaller social network is positively associated with metabolic syndrome. This trend could be partially explained by physical inactivity, especially in older individuals.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, physical activity and health, social determinants, public health

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Research has shown that social network properties are associated with metabolic syndrome, which is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.

What are the new findings?

We found that a small social network is positively associated with metabolic syndrome in Koreans.

The association between social networks and metabolic syndrome is partially mediated by decreased physical activity, especially in older individuals.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

Our study suggests that developing strategies to encourage physical activity in socially isolated individuals could help prevent metabolic syndrome.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a constellation of conditions that occur together and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, including central obesity, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), high triglyceride, hypertension and hyperglycemia. Metabolic syndrome is an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, and its prevalence has markedly increased worldwide over the past several decades.1

A social network, the network of people surrounding an individual, is known to impose health effects on individuals.2 Evidence from the previous studies have indicated that social networks are important determinants of type 2 diabetes,3 obesity,3 4 hypertension5 6 and ischemic heart diseases.5 7 Several models had been proposed to explain the effects of social networks on health: Berkman et al summarized previous studies on the health effects of social networks and suggested that social networks affect psychosocial mechanisms, including social support, social engagement and access to resources, and ultimately manifest as health effects on the individual via health behavior pathways, psychological pathways and physiological pathways.8 Agreeing on the model, Heaney and Israel simplified the hierarchy of health determinants to describe the effects of social networks on health through a social engagement pathway as a hypothesized direct effect.9

Several studies have applied theories on the health effects of social networks in an attempt to investigate indirect pathways and to explain associations between social networks and cardiovascular diseases.10 11 Umberson suggested that a lack of social support can decrease adherence to health behaviors.12 A study on working-class multiethnic adults showed that social influences can affect health behaviors, including exercise and fruit and vegetable consumption.13 Meanwhile, social support has been found to affect self-esteem and a sense of control,14 and thus physical health.15 A study of 887 patients with myocardial infarction reported that depressed patients with larger social networks or who lived with others are more likely to be protected from the negative effects of depressive symptoms,16 indicating the importance of psychological pathways on health.

There is, however, little empirical evidence on mechanisms by which social networks affect metabolic syndrome. Results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study Cohort showed that both the lack of a social network and dissatisfaction with one’s network can increase the risk of metabolic syndrome.17 18 Notwithstanding, attempts to identify direct and indirect health effects of social networks on metabolic syndrome have yet to be made. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to explore possible mechanisms underlying the effect of social networks on metabolism by identifying direct and indirect pathways through which social network properties affect metabolic syndrome.

Methods

Study population

This study was designed as a cross-sectional study of baseline results from The Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research (CMERC) Cohort Study. The CMERC Cohort is a multicenter, community-based cohort designed to investigate the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in Korean adults.19 The study population was recruited at three centers: a community-based, low-risk population was recruited at Yonsei University College of Medicine and Ajou University College of Medicine, and a hospital-based, high-risk population was recruited at Severance Hospital. A total of 8697 community-based participants and 3267 hospital-based participants were recruited. Data on sociodemographic factors, medical history, social network properties and health behaviors were obtained via face-to-face interviews with structured questionnaires. Health examinations, including anthropometric measurement, resting blood pressure measurement and biochemical analyses of fasting blood samples and urine specimens, were conducted.19

Due to sexual heterogeneities in metabolism and social networks, we stratified participants by gender. Female sexual hormones are known to affect insulin sensitivity, glucose homeostasis and adiposity,20 resulting in lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in women before menopause than their male counterparts. The protective effect of estradiol grows weaker as women grow older, and serum estrogen levels decrease after menopause, resulting in a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older women than their male counterparts.21 Meanwhile, several studies have described gender differences in the health effects of social networks and have emphasized a need for gender-specific approaches in further research.16 22

The age range of the community-based participants was 30−64 years, and the age range of the hospital-based participants was 30−80 years. To avoid possible confounding effects from age differences, 1861 participants aged 65 years and older were excluded from final analyses. Also, since demographic and clinical differences between the community-based group and hospital-based group cannot be ignored and since those differences could introduce heterogeneities in social networks and their health effects, two subgroups were analyzed separately in the final analyses.

Independent variable: social network properties

Trained interviewers conducted a systematic face-to-face interview to assess the egocentric social network properties of participants. All social network properties were based on the social network status of the year before baseline evaluation. Measurement of social network properties were conducted in accordance with the methods used in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP).23 We translated social network cards from the NSHAP and adapted them to suit the CMERC Cohort study (online supplementary material 1).

bmjdrc-2020-001272supp001.pdf (569.1KB, pdf)

Among social network properties, we used ‘size of social network’ as a representative variable for quantitative evaluation and ‘closeness of a social network’ for qualitative evaluation. The size of a social network was defined as the total number of network members, including a spouse and up to five people with whom participants discussed important matters. If there were more than five people with whom participants discussed important matters, the participants were asked to name five (online supplementary material 2). The total sizes of social networks ranged from 1 to 6. Perceived closeness between participants and each members of the social network were assessed by asking the following question, with responses rated on a 4-point Likert scale: “How close are you to him/her?” The mean value of perceived closeness between social network members was defined as the closeness of the social network.19

Outcome variable: metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome was defined in accordance with the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel-Ⅲ criteria.24 Metabolic syndrome was defined as the presence of three or more of the following components: central obesity, low HDL-cholesterol, high serum triglyceride, high blood pressure and high fasting glucose. Central obesity was defined as a waist circumference of >90 cm for men and >80 cm for women.25 Low HDL was defined as <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women. High triglyceride was defined as ≥150 mg/dL. High blood pressure was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm Hg or the use of antihypertensive medications. High fasting glucose was defined as ≥100 mg/dL or the use of antidiabetic medications/insulin treatment (online supplementary material 3).

Waist circumference was measured at the middle point between the lower border of the rib cage and iliac crest. Blood samples were collected for lipid profile assessments and fasting glucose measurement. All participants fasted at least 8 hours before providing the blood and urine samples. Bioassays were performed at a designated research laboratory.

Before blood pressure measurement, participants were asked whether they were on antihypertensive medications and if they took their antihypertensive medications within 12 hours before measurement. Also, participants were asked to bring their prescriptions from their doctors and the actual medication they are taking, if possible. We determined whether the participants were on antihypertensive drugs based on prescriptions, actual medication and responses from the participants.

Single arm blood pressure was measured on the right arm. Measurements were conducted on the left arm only if right arm measurements were impossible. Participants rested for 5 min in a seated position before measurement, and they were asked to remain still and relaxed during measurement. A cuff tailored to mid-arm circumference was used, and trained research personnel conducted blood pressure measurements using an automated oscillometric device (HEM-7080, Omron Health, Matsusaka, Japan). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured three times at 2 min intervals on the right arm.

Potential mediators: physical activity, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms

The types, intensity and duration of physical activities that the participants performed during the previous week were obtained using the Korean version of The International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form.26 27 Physical activities were classified as ‘vigorous activities’, ‘moderate activities’ and ‘walking’. Before evaluation, trained research personnel provided examples of each physical activity category to participants (online supplementary material 4). Vigorous activities were considered equivalent to 8.0 metabolic equivalent tasks (METs), moderate activities to 4.0 METs and walking to 3.3 METs. Total MET-hours were calculated by adding the products of METs and exercise hours for each physical activity category.

Systematic interviews were conducted for gathering information on cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. Current status, frequency and average amount of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption were assessed. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) scale, which has been validated for the Korean population.28 The total score for 21 questions in BDI-II was included in the final model.

Covariates

Mean monthly household income and education level were selected as covariates for socioeconomic status. Education level was defined as the last level of education that the participants had graduated or dropped out from. We reclassified education level into three subgroups: primary or lower, secondary and tertiary or higher. We adjusted comorbidities by including diseases included in the Charlson Comorbidity Index in the final model.29

Statistical analyses

There were 813 participants with incomplete data on social network properties and 408 participants with missing lipid profiles. We examined if participants with missing variables were demographically different from those with no missing variables, and some heterogeneities were detected, suggesting that missing data from the dataset were not ‘missing completely at random’.30 To avoid possible biases from missing variables, we imputed missing values by multiple imputation by chained equations (chain length=10). Sensitivity analyses on the original dataset were also conducted, along with analyses on the imputed dataset, for estimation of biases. During sensitivity analyses, 1221 participants with either missing social network properties or missing lipid profiles were excluded.

T-tests and χ2 tests were used to compare sex-specific mean values and proportions of baseline socioeconomic status variables, social network properties, health behaviors and measures related to metabolic syndrome. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the association between social network properties and metabolic syndrome or individual metabolic abnormalities (metabolic syndrome components) after controlling for household income, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, depressive symptoms and comorbidities. Both categorical and linear models were used to estimate ORs. In the categorical model, the subgroup with a larger network size (size ≥4) and with a closer social network (closeness ≥3.2) was set as the reference group, and ORs for a smaller network size (size ≤3) and less close social network (closeness <3.2) were estimated. In the linear model, ORs for one unit decrease in network size and social network closeness were estimated. The associations between social network properties and potential mediators were also evaluated using multiple logistic regression.

Mediation analyses were conducted using the ‘mediation’ package in R software. The mediation package is a statistical tool developed by Imai et al31 to conduct mediation analyses, which are widely used in the fields of medicine32 and epidemiology.33 The package takes mediator and outcome models as inputs and returns estimated sizes of mediation effects. First, we input the logistic regression model that had the potential mediators as dependent variables and other covariates as independent variables. Then, we input the logistic regression model that had metabolic syndrome as the dependent variable and mediator, alongside with other covariates as independent variables. Finally, we estimated the direct effects, indirect effects and their 95% CIs by quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo methods, with 5000 simulations each.34 All analyses were conducted using SAS software V.9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R software V.3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2018). To investigate age heterogeneities in the effects of social networks, age-specific direct effects of network size and the indirect effect through physical activity for each subgroup were estimated and plotted.

Results

Characteristics of CMERC Cohort participants

A total of 8034 participants from the community-based population and 1683 participants from the hospital-based population with complete information on social network properties and lipid profiles were included in the final analyses. In the community-based group, 777 men (27.85%) and 923 women (17.60%) had metabolic syndrome. In the hospital-based group, 379 men (38.99%) and 305 women (42.90%) had metabolic syndrome.

Social network sizes were smaller in participants with metabolic syndrome in all subgroups, except in hospital-based men. Social network closeness did not differ with the presence of metabolic syndrome in all subgroups. In the community-based group, participants with metabolic syndrome reported less physical activity in both men and women; no differences were detected in the hospital-based group (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research (CMERC) Cohort participants (n=10 103)

| Community-based population (n=8097) | ||||||

| Variables | Men (n=2808) | Women (n=5289) | ||||

| Controls (n=2004) |

Cases (n=804) |

P value | Controls (n=4336) |

Controls (n=953) |

P value | |

| Age, mean (SD) (n=8097) | 50.56 (9.60) | 51.16 (8.67) | 0.112 | 51.04 (8.52) | 55.16 (6.32) | <0.001 |

| Household income, KRW/year, N (%) (n=8097) | 0.225 | 0.305 | ||||

| <25 p (24M) | 536 (26.75) | 203 (25.25) | 843 (19.44) | 203 (21.30) | ||

| 25 p–50 p (48M) | 344 (17.17) | 118 (14.68) | 955 (22.02) | 228 (23.92) | ||

| 50 p–75 p (75.6M) | 611 (30.48) | 256 (31.84) | 1448 (33.40) | 291 (30.54) | ||

| ≥75 p | 503 (25.10) | 225 (27.99) | 1070 (24.68) | 227 (23.82) | ||

| N/A | 10 (0.50) | 2 (0.24) | 20 (0.46) | 4 (0.42) | ||

| Degree of education, N (%) (n=8097) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Primary or lower | 58 (2.89) | 20 (2.49) | 235 (5.42) | 104 (10.91) | ||

| Secondary | 779 (38.87) | 376 (46.77) | 2490 (57.43) | 638 (66.95) | ||

| Tertiary or higher | 1167 (58.24) | 408 (50.74) | 1611 (37.15) | 210 (22.04) | ||

| N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.10) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, N (%) (n=8097) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 792 (39.52) | 247 (30.72) | 1648 (38.01) | 162 (17.00) | ||

| 1 | 579 (28.89) | 270 (33.58) | 1569 (36.19) | 321 (33.68) | ||

| 2 | 465 (23.20) | 196 (24.38) | 812 (18.73) | 302 (31.69) | ||

| 3 | 139 (6.94) | 78 (9.70) | 241 (5.56) | 113 (11.86) | ||

| ≥4 | 29 (1.45) | 13 (1.62) | 66 (1.51) | 55 (5.77) | ||

| BDI-II scores, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 8.76 (6.74) | 9.35 (6.82) | 0.036 | 11.20 (7.49) | 11.81 (8.10) | 0.033 |

| Social network properties | ||||||

| Size of social network, mean (SD) (n=8097) | 3.28 (1.76) | 3.07 (1.74) | 0.003 | 3.60 (1.62) | 3.27 (1.55) | <0.001 |

| Social network closeness, mean (SD) (n=8038) | 3.20 (0.61) | 3.20 (0.59) | 0.835 | 3.14 (0.61) | 3.10 (0.62) | 0.084 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||||

| Physically activity in MET-hours, N (%) (n=8097) | 11.36 (13.48) | 9.90 (12.34) | 0.006 | 7.59 (9.82) | 6.62 (8.77) | 0.003 |

| Current smoker, N (%) (n=8097) | 647 (32.29) | 276 (34.33) | 0.319 | 122 (2.81) | 15 (1.57) | 0.039 |

| Current drinker, N (%) (n=8097) | 1684 (84.03) | 693 (86.19) | 0.168 | 2816 (65.17) | 559 (58.66) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome components | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) (n=8097) | 24.25 (2.52) | 27.15 (2.71) | <0.001 | 23.08 (2.75) | 25.95 (3.07) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD) (n=8096) | 85.12 (6.88) | 93.87 (6.66) | <0.001 | 77.79 (7.73) | 86.78 (7.16) | <0.001 |

| Mean systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 122.21 (12.35) | 132.34 (13.99) | <0.001 | 113.56 (13.26) | 127.84 (15.59) | <0.001 |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 78.36 (8.95) | 85.67 (9.90) | <0.001 | 72.41 (8.60) | 80.10 (9.89) | <0.001 |

| Serum HDL, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 52.34 (12.05) | 43.71 (10.63) | <0.001 | 4335 (61.60) | 47.49 (10.10) | <0.001 |

| Serum TG, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 132.49 (92.13) | 233.37 (159.78) | <0.001 | 100.51 (48.87) | 185.58 (84.07) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD) (n=8095) | 94.93 (19.45) | 111.91 (28.86) | <0.001 | 98.03 (12.97) | 107.46 (28.49) | <0.001 |

| Hospital-based population (n=2006) | ||||||

| Variables | Men (n=1168) | Women (n=838) | ||||

| Controls (n=697) |

Cases (n=471) |

P value | Controls (n=473) |

Controls (n=365) |

P value | |

| Age, mean (SD) (n=2006) | 52.24 (8.42) | 52.84 (8.23) | 0.234 | 52.91 (8.23) | 54.49 (7.77) | 0.005 |

| Household income, KRW/year, N (%) (n=2006) | 0.732 | 0.251 | ||||

| <25 p (24M) | 126 (18.08) | 84 (17.83) | 65 (13.74) | 59 (16.16) | ||

| 25 p–50 p (48M) | 96 (13.77) | 65 (13.80) | 84 (17.76) | 56 (15.34) | ||

| 50 p–75 p (75.6M) | 175 (25.11) | 13 (21.87) | 104 (21.99) | 73 (20.00) | ||

| ≥75 p | 151 (21.66) | 109 (23.14) | 98 (20.72) | 63 (17.26) | ||

| N/A | 149 (21.38) | 110 (23.35) | 122 (25.79) | 114 (31.23) | ||

| Degree of education, N (%) (n=2006) | 0.607 | 0.012 | ||||

| Primary or lower | 34 (4.88) | 29 (6.16) | 56 (11.84) | 65 (17.81) | ||

| Secondary | 270 (38.73) | 168 (35.67) | 241 (50.95) | 198 (54.25) | ||

| Tertiary or higher | 391 (56.10) | 272 (57.75) | 175 (37.00) | 101 (27.67) | ||

| N/A | 2 (0.29) | 2 (0.42) | 1 (0.21) | 1 (0.27) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, N (%) (n=2006) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 79 (11.33) | 60 (12.74) | 42 (8.88) | 28 (7.67) | ||

| 1 | 126 (18.08) | 76 (16.13) | 94 (19.87) | 46 (12.60) | ||

| 2 | 234 (33.57) | 116 (24.63) | 186 (39.32) | 100 (27.40) | ||

| 3 | 135 (19.37) | 97 (20.59) | 89 (18.82) | 80 (21.92) | ||

| ≥4 | 123 (17.65) | 122 (25.90) | 62 (13.11) | 111 (30.41) | ||

| BDI-II scores, mean (SD) (n=1997) | 8.79 (7.33) | 9.66 (7.05) | 0.045 | 10.96 (8.58) | 11.97 (8.48) | 0.092 |

| Social network properties | ||||||

| Size of social network, mean (SD) (n=2005) | 2.10 (1.41) | 2.21 (1.46) | 0.211 | 2.58 (1.48) | 2.38 (1.28) | 0.037 |

| Social network closeness, mean (SD) (n=1939) | 3.47 (0.64) | 3.45 (0.66) | 0.470 | 3.48 (0.64) | 3.41 (0.67) | 0.133 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||||

| Physically activity in MET-hours, N (%) (n=2006) | 9.95 (13.14) | 9.31 (13.09) | 0.414 | 6.54 (7.81) | 6.16 (8.97) | 0.517 |

| Current smoker, N (%) (n=2006) | 170 (24.39) | 153 (32.48) | 0.003 | 14 (2.96) | 13 (3.56) | 0.625 |

| Current drinker, N (%) (n=2006) | 456 (65.42) | 303 (64.33) | 0.701 | 200 (59.70) | 135 (40.30) | 0.120 |

| Metabolic syndrome components | ||||||

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) (n=2006) | 24.33 (3.26) | 27.42 (3.47) | <0.001 | 23.07 (3.56) | 26.20 (3.97) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD) (n=2002) | 85.99 (8.12) | 94.56 (8.18) | <0.001 | 78.66 (9.47) | 88.30 (9.29) | <0.001 |

| Mean systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) (n=2004) | 124.64 (16.09) | 133.19 (17.11) | <0.001 | 118.64 (14.59) | 130.18 (15.97) | <0.001 |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) (n=2004) | 78.40 (10.21) | 82.20 (10.02) | <0.001 | 74.62 (9.75) | 78.93 (9.96) | <0.001 |

| Serum HDL, mean (SD) (n=1800) | 51.06 (12.60) | 40.27 (10.80) | <0.001 | 60.26 (19.25) | 46.82 (12.91) | <0.001 |

| Serum TG, mean (SD) (n=1830) | 97.06 (65.92) | 178.10 (163.13) | <0.001 | 86.89 (55.51) | 146.17 (93.12) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD) (n=1961) | 108.53 (29.12) | 125.73 (40.24) | <0.001 | 99.91 (22.10) | 120.18 (38.24) | <0.001 |

Significant values are in bold.

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; KRW, Korean Won; MET, metabolic equivalent task; TG, triglyceride.

Social network properties and metabolic syndrome

In the community-based group, a small social network was positively associated with metabolic syndrome in both men and in women. In the hospital-based group, however, the same positive association was only apparent in women. Social network closeness was not associated with metabolic syndrome in any subgroup (table 2). Sensitivity analyses with the original dataset presented similar trends for the association (online supplementary material 5).

Table 2.

Gender-specific associations between social network properties and metabolic syndrome (n=10 103)*

| Gender | Social network properties | No. of people | No. (%) metabolic syndrome | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | Model 4¶ |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Community-based low-risk participants (n=8097) | |||||||

| Men (n=2808) |

Size of social network | ||||||

| Large (≥4) | 1134 | 291 (25.66) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Small (≤3) | 1674 | 513 (30.65) | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.50) | 1.25 (1.05 to 1.48) | 1.23 (1.04 to 1.47) | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.43) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) | |||

| Social network closeness | |||||||

| High (≥3.2) | 1373 | 376 (27.39) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Low (<3.2) | 1435 | 428 (29.83) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30) | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.28) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.27) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.16) | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.15) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | |||

| Women (n=5289) |

Size of social network | ||||||

| Large (≥4) | 2491 | 380 (15.25) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Small (≤3) | 2798 | 573 (20.48) | 1.35 (1.17 to 1.57) | 1.32 (1.14 to 1.53) | 1.28 (1.11 to 1.49) | 1.26 (1.09 to 1.46) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.15) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | |||

| Social network closeness | |||||||

| High (≥3.2) | 2504 | 436 (17.41) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Low (<3.2) | 2785 | 517 (18.56) | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.08) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.04) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.05) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.05) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.05) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.05) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.05) | |||

| Hospital-based high-risk participants (n=2006) | |||||||

| Men (n=1168) |

Size of social network | ||||||

| Large (≥4) | 183 | 75 (40.98) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Small (≤3) | 985 | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.33) | 0.98 (0.71 to 1.36) | 0.95 (0.69 to 1.32) | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | ||

| Per 1-unit decrease | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.03) | 0.85 (0.87 to 1.03) | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.02) | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.02) | |||

| Social network closeness | |||||||

| High (≥3.2) | 725 | 292 (40.28) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Low (<3.2) | 443 | 179 (40.41) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.27) | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.30) | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.22) | 0.94 (0.73 to 1.21) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24) | 1.06 (0.88 to 1.27) | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.20) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.19) | |||

| Women (n=838) |

Size of social network | ||||||

| Large (≥4) | 167 | 60 (35.93) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Small (≤3) | 671 | 305 (45.45) | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.07) | 1.40 (0.97 to 2.00) | 1.47 (1.01 to 2.13) | 1.46 (1.00 to 2.12) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.21) | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.19) | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.21) | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.20) | |||

| Social network closeness | |||||||

| High (≥3.2) | 542 | 226 (41.70) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Low (<3.2) | 296 | 139 (46.96) | 1.16 (0.87 to 1.54) | 1.16 (0.86 to 1.56) | 1.07 (0.79 to 1.44) | 1.06 (0.78 to 1.44) | |

| Per 1-unit decrease | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.37) | 1.12 (0.91 to 1.39) | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.31) | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.31) | |||

Significant values are in bold.

*All results are from the dataset after multiple imputation by chained equations, with a chain length of 10.

†Adjusted for age.

‡Adjusted for age, household income and education.

§Adjusted for age, household income, education and comorbidities.

¶Adjusted for age, household income, education, comorbidities, drinking status, smoking status and physical activity.

When analyzed for individual metabolic syndrome components, instead of metabolic syndrome, a small social network was positively associated with central obesity (men: OR=1.19, 95% CI (1.01 to 1.39); women: OR=1.29, 95% CI (1.15 to 1.45)) and high fasting glucose (men: OR=1.34, 95% CI (1.13 to 1.58); women: OR=1.23, 95% CI (1.07 to 1.42)) in both men and women in the community-based population. Low social network closeness was positively associated with central obesity in women, and no other associations were found in men or women. In the hospital-based population, neither the size nor the social network closeness was associated with metabolic syndrome components in men. In women, there were some trends of a positive association between network size and metabolic syndrome components, although with only borderline significance (online supplementary material 6).

Mediating effect of lifestyle factors

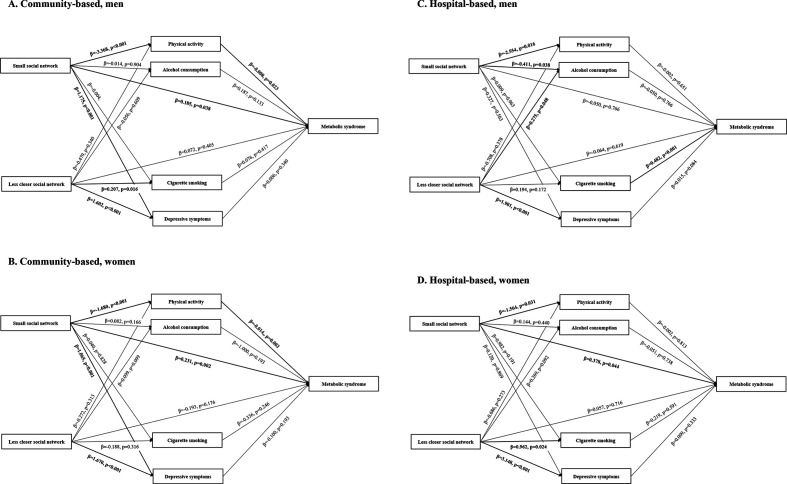

Small network size was negatively associated with physical activity in both the community-based and hospital-based groups. Social network closeness was not associated with physical activity in any subgroups. Cigarette smoking was positively associated with metabolic syndrome in only low-risk females. There were no clear associations between depressive symptoms and metabolic syndrome in any subgroup (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the associations among social network properties, lifestyle factors and metabolic syndrome in men and women.* (A) Community-based, men, (B) community-based, women, (C) hospital-based, men, (D) hospital-based, women. *Adjusted for age, household income, education level and comorbidities.

In the community-based group, physical activity mediated the association between social network size and metabolic syndrome in both sexes (men: effect size (ES)=5.2×10−3, p=0.024; women: ES=3.1×10−3, p<0.001). Indirect effects of social network size through alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms were not significant in any subgroup. Neither direct nor indirect effects of social network closeness on metabolic syndrome were significant (table 3). In the hospital-based group, a direct effect for network size was detected in women. No indirect effects for network size and closeness were detected. Significant direct and indirect effects for network size were also detected in sensitivity analyses (online supplementary material 7).

Table 3.

Direct and indirect effects of social network properties on metabolic syndrome (n=10 103)*

| Community-based low-risk participants (n=8097) | ||||

| Social network properties | Men (n=2808) | Women (n=5289) | ||

| Effect size (95% CI)† (×10−2) | P value | Effect size (95% CI)† (×10−2) | P value | |

| Size of social network | ||||

| Direct effect | 3.65 (1.74 to 7.07) | 0.040 | 3.19 (1.15 to 5.20) | 0.002 |

| Indirect effect—physical activity | 0.52 (0.08 to 1.05) | 0.024 | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.55) | <0.001 |

| Indirect effect—cigarette smoking | 0.00 (−0.11 to 0.11) | 0.977 | 0.00 (−0.06 to 0.48) | 0.910 |

| Indirect effect—alcohol consumption | −0.01 (−0.16 to 0.14) | 0.933 | −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.03) | 0.420 |

| Indirect effect—depressive symptoms | 0.14 (−0.15 to 0.47) | 0.345 | 0.00 (−0.15 to 0.14) | 0.994 |

| Social network closeness | ||||

| Direct effect | 1.45 (−1.99 to 4.84) | 0.396 | −1.40 (−3.43 to 0.56) | 0.176 |

| Indirect effect—physical activity | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.29) | 0.362 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.17) | 0.314 |

| Indirect effect—cigarette smoking | 0.06 (−0.10 to 0.29) | 0.445 | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.09) | 0.554 |

| Indirect effect—alcohol consumption | −0.03 (−0.20 to 0.11) | 0.697 | −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.03) | 0.358 |

| Indirect effect—depressive symptoms | 0.16 (−0.16 to 0.50) | 0.340 | 0.00 (−0.23 to 0.23) | 0.991 |

| Hospital-based high-risk participants (n=2006) | ||||

| Social network properties | Men (n=1168) | Women (n=838) | ||

| Effect size (95% CI)† (×10−2) | P value | Effect size (95% CI)† (×10−2) | P value | |

| Size of social network | ||||

| Direct effect | −1.12 (−9.07 to 6.51) | 0.802 | 8.40 (0.09 to 16.23) | 0.046 |

| Indirect effect—physical activity | 0.13 (−0.47 to 0.80) | 0.649 | 0.07 (−0.61 to 0.82) | 0.824 |

| Indirect effect—cigarette smoking | −0.01 (−1.02 to 0.92) | 0.991 | 0.12 (−0.41 to 0.83) | 0.662 |

| Indirect effect—alcohol consumption | −0.05 (−0.64 to 0.51) | 0.857 | −0.04 (−0.50 to 0.37) | 0.870 |

| Indirect effect—depressive symptoms | 0.12 (−0.30 to 0.67) | 0.601 | 0.03 (−0.36 to 5.07) | 0.894 |

| Social network closeness | ||||

| Direct effect | −1.44 (−7.34 to 4.19) | 0.630 | 1.33 (−5.69 to 8.18) | 0.705 |

| Indirect effect—physical activity | 0.04 (−0.18 to 0.33) | 0.790 | 0.04 (−0.33 to 0.47) | 0.854 |

| Indirect effect—cigarette smoking | 0.42 (−0.29 to 1.33) | 0.267 | 0.20 (−0.51 to 1.14) | 0.598 |

| Indirect effect—alcohol consumption | −0.03 (−0.47 to 0.36) | 0.859 | −0.07 (−0.67 to 4.34) | 0.761 |

| Indirect effect—depressive symptoms | 0.66 (−0.09 to 1.58) | 0.083 | 0.60 (−0.70 to 1.97) | 0.344 |

Estimated using the ‘mediation’ package. The quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo method was applied with 5000 times of simulation each.

Significant values are in bold.

*All results are from the dataset after multiple imputation by chained equations, with a chain length of 10.

†Adjusted for age, household income, education level, comorbidities and social network closeness.

In the community-based group, indirect effects on central obesity, high triglyceride and high fasting glucose components were detected in both men and women. In women, indirect effects on low HDL-cholesterol components were also detected. In the hospital-based group, only indirect effects on central obesity were detected in men (ES=6.4×10−3, p=0.049); no indirect effects were detected in women (online supplementary material 8).

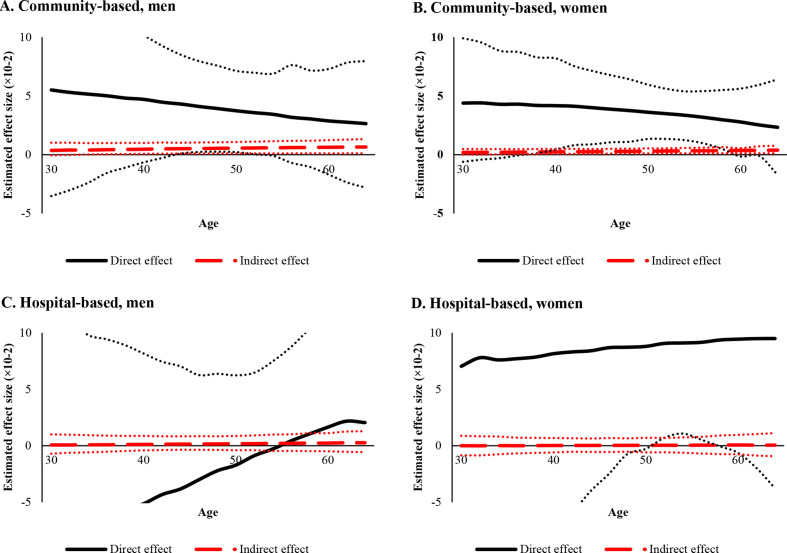

Both direct and indirect effect were moderated by age. In the community-based group, the direct effect of network size was smaller in older participants, while indirect effects through physical activity were larger. In the hospital-based group, since effect sizes were insignificant throughout most of the age range, definite conclusions could not be drawn (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Age-specific direct effect of size of social network and indirect effect through physical activity.* (A) Community-based, men, (B) community-based, women, (C) hospital-based, men, (D) hospital-based, women. *Adjusted for age, household income, education level, comorbidities, social network closeness, alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking. In community-based population, age-specific indirect effect of network size through physical activity was larger in older age. In contrast, no significant trends in indirect effects were found in hospital-based population.

Discussion

In this study, we found a small social network to be positively associated with a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in low-risk individuals. Social network closeness showed no association with metabolic syndrome. Interestingly, several lifestyle factors were associated with social network properties, and our mediation analyses revealed that physical inactivity can explain the association between a small social network and metabolic syndrome. In high-risk individuals, a direct effect for network size was detected only in women, and no indirect effects through lifestyle factors were detected.

Previous studies have consistently shown a positive association between poor social networks and metabolic syndrome, although underlying mechanisms thereof have remained largely unknown. Several studies have suggested a possible correlation between poor social network status and lifestyle; however, only a few previous studies have attempted to quantify the mediating effects of lifestyle factors on the association between social network and metabolic syndrome. To address this knowledge gap, we investigated the association between social network properties and metabolic syndrome by analyzing a relatively large population (n>10 000). Furthermore, we examined if lifestyle factors mediated the health effects of social network properties, since it is suggested that social environments affect lifestyle.35

Overall, only social network size, not closeness, showed a significant effect on metabolic syndrome. However, previous studies have reported a significant effect for social network quality on health.36 One study that explored the coping mechanisms of Asian and European Americans in response to stress reported that among social support mechanisms, Asian Americans relied less on emotional support than European Americans, unlike instrumental support where no significant differences were observed between Asian and European Americans.37 People from collectivistic cultures tend to seek social support, particularly emotional support, less than those from individualistic cultures, and thus, the effectiveness of support seeking is attenuated.38 In individualistic cultures, a relationship is a means through which to promote individual goals; thus, members of the network can actively seek help from other members. In contrast, in collectivistic cultures, pursuit of individual goals is a risk factor for relationship-related strain; hence, members of the network try not to burden each other.37 38 Although this would not fully explain the tendencies noted in our study, we suspect that the health benefit of social network quantity, which is correlated with instrumental support, is more prominent than that of network quality, which is correlated with emotional support.

Interestingly, women were more likely to be affected by network size than their male counterparts. Several studies have emphasized gender differences in the effect of social network on health and the need for gender-specific approaches in further research.22 39 These gender differences mainly rise from coping mechanisms against stress: women have evolved to use a ‘tend-and-befriend mechanism’, which reflects a reliance on social groups to avoid stressors and threats, and therefore usually receive more benefit from social networks and social support than men do.22 We were able to detect gender differences in the health effects of social networks, especially in high-risk individuals. It could be postulated that coping mechanisms come into play as risk for cardiovascular and metabolic disease increases, resulting in amplified gender differences in the effects of social networks on health.

Our analyses showed that reduced physical activity could explain, at least in part, the association between social networks and metabolic syndrome. Individuals with a small social network are likely to be less physically active.40 The social control theory suggests that an abundance of social network resources can improve the lifestyles of network members, whereby members of a social network are obligated to adopt healthy behaviors, resulting in the promotion of healthy behaviors in other members.41 Individuals with a small network lack these influences. Evidence indicates that negative effects can occur due to feelings of loneliness and that social isolation can lead to decreased physical activity.42 43 Our mediation analysis indicated that a small social network is both directly and indirectly (through physical inactivity) associated with the risk of having metabolic syndrome. This finding implies that lifestyle factors, including physical inactivity, can increase the risk of metabolic syndrome in individuals with insufficient social network resources.

Age-specific estimates suggest that the impact of physical activity or inactivity on health increases with age. Several studies have suggested that physical activity can decrease risk for metabolic syndrome,44 especially in middle-aged or older populations.45 46 Physical activity can reduce insulin resistance,47 and low physical activity is associated with several metabolic syndrome components.48 As the risk for metabolic syndrome increases as people grow older, the role of physical activity in health increases, and this could have been reflected in the greater indirect effect of a small social network through physical activity on metabolic syndrome.

One might argue that the lack of physical activity decreases an individual’s opportunity to create and maintain new social ties, ultimately causing metabolic syndrome through a smaller social network. However, a previous longitudinal analysis40 of loneliness and physical activity explained that whereas physical activity in baseline years does not predict subsequent loneliness or size of social network, loneliness in baseline years is able to predict subsequent decreases in physical activity. Furthermore, in our study, social network information was based on the participants’ network status in the previous year and was obtained through an interview; physical activity information was based on the physical activities that the patient had performed in the previous week. Therefore, the temporality between exposure and mediator would reduce the possibility of reverse causality.

Alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking did not significantly mediate the association in either men or women. Drinking and smoking remain important aspects of socialization in South Korea and are more prominent in the older population. While a larger social network can prevent the development of hazardous lifestyles, for network members who encourage smoking or drinking, it might actually increase the risk of drinking and smoking.49 50 This might have diminished the effect of social networks on drinking and smoking habits. Since the social context of drinking and smoking is rapidly changing in Korean society, studies on younger individuals are warranted to fully understand the relationship between social networks and lifestyle factors.

To our knowledge, this study is one of only a few to have attempted to investigate the association between social network and metabolic syndrome in the Korean population. Moreover, we investigated associations between social networks and lifestyle factors, and quantified the extent to which the association of social networks with metabolic syndrome is related by performing mediation analyses.

However, several limitations should be considered in interpreting our results. First, in spite of the relatively large sample size (n>10 000), results from our mediation analyses cannot be used to infer causality due to cross-sectional nature of the study, even though temporality between exposure, mediator and outcome variables was maintained. To elucidate this temporal association, follow-up evaluation is in action, and longitudinal cohort data would be able to provide more comprehensive understanding of the relationships among social network, lifestyle factors and metabolic syndrome. Second, our results might not be generalizable to the entire population since the included participants were sampled from relatively urban districts. As urbanicity affects social network properties and their health outcomes,51 results from our study might be affected by urbanicity of population. A nationwide study with national-level indicators of social network and psychosocial factors could help demonstrate the health roles of social networks and its association with metabolic syndrome. Lastly, since we evaluated social network properties by an interview, response bias may exist. For instance, depressed individuals might underestimate their closeness with network members. In contrast, social network size, which was defined as the number of people with whom participants have discussed important issues, is a variable that is less likely affected by depressive symptoms. Since there were no differences in the direction of association when stratified by depressive symptoms, the impact of response biases in our study is likely to be limited in our model.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study found a positive association between small network size and metabolic syndrome and reported the mediating effect of physical inactivity. This could imply that the excess risk of metabolic syndrome in socially isolated individuals could be attributed to physical inactivity and that exercising could provide protective health effects in individuals with a small social network, especially in older individuals. Hence, healthcare providers should recognize the negative health effects of social isolation and subsequent decrease in physical activity on metabolic syndrome and develop strategies to increase physical activity among people with small social networks.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. Funding statement has been updated.

Contributors: Study design and concept: KK and SJJ. Systematic review on previous related studies: KK and JMB. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: KK, SJJ, HCK, DJK, SP and YY. Statistical analysis: KK. Drafting of the manuscript: KK. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SJJ, JMB, HCK, HWY, HJ and YY. Obtained funding: SJJ, HCK, DJK and SP. Study supervision: SJJ.

Funding: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Grant number 2018R1C1B5083722 and grant number 2020R1C1C1003502).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea (4-2013-0661, 4-2013-0581) and Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, Korea (AJIRB-BMR-SUR-13-272). All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center (CMERC) Cohort is a cohort study, which aims to identify novel risk factors of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and to develop evidence-based prevention strategies for those diseases. The CMERC Cohort consists of two prospective cohorts, a community-based general population cohort and its sister cohort, which is a hospital-based high-risk patient cohort. Baseline study was conducted between 2013 and 2018, and follow-up study is currently in progress. Baseline measurements assessed sociodemographic factors, medical history, health-related behaviors, psychological health, social network and support, anthropometry, body composition and resting blood pressure and comprised electrocardiography, carotid artery ultrasonography, fasting blood analysis and urinalysis. Please contact cmerc@yuhs.ac for access to CMERC data.

References

- 1.Bray GA, Bellanger T. Epidemiology, trends, and morbidities of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine 2006;29:109–18. 10.1385/ENDO:29:1:109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, et al. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:637–51. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henning CHCA, Zarnekow N, Hedtrich J, et al. Identification of direct and indirect social network effects in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance in obese human subjects. PLoS One 2014;9:e93860. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 2007;357:370–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, Ernst D, et al. Social networks as predictors of ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke and hypertension: incidence, survival and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:659–66. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90138-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redondo-Sendino A, Guallar-Castillón P, Banegas JR, et al. [Relationship between social network and hypertension in older people in Spain]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2005;58:1294–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welin L, Larsson B, Svärdsudd K, et al. Social network and activities in relation to mortality from cardiovascular diseases, cancer and other causes: a 12 year follow up of the study of men born in 1913 and 1923. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992;46:127–32. 10.1136/jech.46.2.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:843–57. This paper is adapted from Berkman LF & Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support and health. In L F Berkman & I Kawachi, Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; and Brissette I, Cohen S, Seeman T. Measuring social integration and social networks. In S Cohen, L Underwood & B Gottlieb, Social Support Measurements and Intervention. New York: Oxford University Press. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heaney CA, Israel BA. Social networks and social support In: Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4, 2008: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han SH, Tavares JL, Evans M, et al. Incident cardiovascular disease, and mortality: health behaviors mediation. J Aging Health 2017;29:268–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Ahluwalia IB, Galuska DA. Social relationships and cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings from the third National health and nutrition examination survey. Prev Med 2000;30:83–92. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: social control as a dimension of social integration. J Health Soc Behav 1987;28:306–19. 10.2307/2136848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmons KM, Barbeau EM, Gutheil C, et al. Social influences, social context, and health behaviors among working-class, multi-ethnic adults. Health Educ Behav 2007;34:315–34. 10.1177/1090198106288011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolger N, Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: experimental evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 2007;92:458–75. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw BA, Krause N, Chatters LM, et al. Emotional support from parents early in life, aging, and health. Psychol Aging 2004;19:4–12. 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, et al. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000;101:1919–24. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.16.1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prescott E, Godtfredsen N, Osler M, et al. Social gradient in the metabolic syndrome not explained by psychosocial and behavioural factors: evidence from the Copenhagen City heart study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:405–12. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32800ff169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen JM, Lund R, Andersen I, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:41–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shim JS, Song BM, Lee JH, et al. Cohort profile: the cardiovascular and metabolic diseases etiology research center cohort in Korea. Yonsei Med J 2019;60:804–10. 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng J-Y, Hsieh P-S, Huang J-P, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor is crucial for resveratrol-stimulating muscular glucose uptake via both insulin-dependent and -independent pathways. Diabetes 2008;57:1814–23. 10.2337/db07-1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awa WL, Fach E, Krakow D, et al. Type 2 diabetes from pediatric to geriatric age: analysis of gender and obesity among 120,183 patients from the German/Austrian DPV database. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167:245–54. 10.1530/EJE-12-0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, et al. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev 2000;107:411–29. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornwell B, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. Social networks in the NSHAP study: rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64 Suppl 1:i47–55. 10.1093/geronb/gbp042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart Association/National heart, lung, and blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan C-E, Ma S, Wai D, et al. Can we apply the National cholesterol education program adult treatment panel definition of the metabolic syndrome to Asians? Diabetes Care 2004;27:1182–6. 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, et al. Validity of the International physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:115. 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.JY O, Yang YJ, Kim BS, et al. Validity and reliability of Korean version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) short form. J Korean Acad Fam Med 2007;28:532–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim S-Y, Lee E-J, Jeong S-W, et al. The validation study of Beck depression scale 2 in Korean version. Anxiety and mood 2011;7:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D, et al. Causal Mediation Analysis Using R : Vinod H, Advances in social science research using R. lecture notes in statistics. 196 New York: Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serrano-Pozo A, Qian J, Monsell SE, et al. APOE ε2 is associated with milder clinical and pathological Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2015;77:917–29. 10.1002/ana.24369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergh C, Udumyan R, Fall K, et al. Stress resilience and physical fitness in adolescence and risk of coronary heart disease in middle age. Heart 2015;101:623–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, et al. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macdonald-Wallis K, Jago R, Sterne JAC. Social network analysis of childhood and youth physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:636–42. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amieva H, Stoykova R, Matharan F, et al. What aspects of social network are protective for dementia? not the quantity but the quality of social interactions is protective up to 15 years later. Psychosom Med 2010;72:905–11. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f5e121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, et al. Culture and social support: who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;87:354–62. 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HS, Sherman DK, Ko D, et al. Pursuit of comfort and pursuit of harmony: culture, relationships, and social support seeking. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2006;32:1595–607. 10.1177/0146167206291991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rennemark M, Hagberg B. Gender specific associations between social network and health behavior in old age. Aging Ment Health 1999;3:320–7. 10.1080/13607869956091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology;28:354–63. 10.1037/a0014400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: social control as a dimension of social integration. J Health Soc Behav 1987;28:306–19. 10.2307/2136848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dergance JM, Mouton CP, Lichtenstein MJ, et al. Potential mediators of ethnic differences in physical activity in older Mexican Americans and European Americans: results from the San Antonio longitudinal study of aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1240–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ong AD, Van Dulmen MH. Handbook of methods in positive psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laaksonen DE, Lakka H-M, Lynch J, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and vigorous leisure-time physical activity modify the association of small size at birth with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2156–64. 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rennie KL, McCarthy N, Yazdgerdi S, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with both vigorous and moderate physical activity. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:600–6. 10.1093/ije/dyg179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bianchi G, Rossi V, Muscari A, et al. Physical activity is negatively associated with the metabolic syndrome in the elderly. QJM 2008;101:713–21. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersen JL, Schjerling P, Andersen LL, et al. Resistance training and insulin action in humans: effects of de-training. J Physiol 2003;551:1049–58. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dotevall A, Johansson S, Wilhelmsen L, et al. Increased levels of triglycerides, BMI and blood pressure and low physical activity increase the risk of diabetes in Swedish women. A prospective 18-year follow-up of the BEDA study. Diabet Med 2004;21:615–22. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yun EH, Kang YH, Lim MK, et al. The role of social support and social networks in smoking behavior among middle and older aged people in rural areas of South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:78. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hofstetter CR, Clapp JD, Allem J-P, et al. Social networks and alcohol consumption among first generation Chinese and Korean immigrants in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Int J Alcohol Drug Res 2014;3:245–55. 10.7895/ijadr.v3i4.188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim J-M, Stewart R, Shin I-S, et al. Lifetime urban/rural residence, social support and late-life depression in Korea. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:843–51. 10.1002/gps.1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2020-001272supp001.pdf (569.1KB, pdf)