Abstract

Mammalian SPAG6, the orthologue of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii PF16, is a component of the central apparatus of the “9+2” axoneme that controls ciliary/flagellar motility, including sperm motility. Recent studies revealed that SPAG6 has functions beyond its role in the central apparatus. Hence, we re-examined the role of SPAG6 in male fertility. In wild-type mice, SPAG6 was present in cytoplasmic vesicles in spermatocytes, the acrosome of round and elongating spermatids, and the manchette of elongating spermatids. Spag6-deficient testes showed abnormal spermatogenesis, with abnormalities in male germ cell morphology consistent with the multi-compartment pattern of SPAG6 localization. The armadillo repeat domain of mouse SPAG6 was used as a bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen, and several proteins with diverse functions appeared multiple times, including Snapin, SPINK2, and COPS5. Snapin has a similar localization to SPAG6 in male germ cells, and SPINK2, a key protein in acrosome biogenesis, was dramatically reduced in Spag6-deficient mice which have defective acrosomes. SPAG16L, another SPAG6 binding partner, lost its localization to the manchette in Spag6-deficient mice. Our findings demonstrate that SPAG6 is a multi-functional protein that not only regulates sperm motility, but also plays roles in spermatogenesis in multiple cellular compartments involving multiple protein partners.

Keywords: vesicle trafficking, cargo transport, acrosome biogenesis, manchette

Introduction

Sperm associated antigen 6 (SPAG6) was first identified in a human testis cDNA expression library (Neilson et al. 1999, Sapiro et al. 2000, Sapiro et al. 2002). It is a critical protein in the assembly and structural integrity of the sperm tail axoneme and is necessary for flagellar motility (Sapiro et al. 2002). Mammalian SPAG6 is the orthologue of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii PF16, which encodes a component of the central apparatus of the “9+2” axoneme, and is essential for flagellar mobility (Neilson et al. 1999, Sapiro et al. 2000). Mutations in the Chlamydomonas PF16 gene cause flagellar paralysis and instability of the C1 microtubule of the central apparatus (Smith & Lefebvre 1996). Spag6/PF16 has been shown to regulate flagellar motility in other model organisms, including trypanosomes, Plasmodium and Giardia (Branche et al. 2006, Straschil et al. 2010, House et al. 2011). Global knockout of Spag6 in mice resulted in approximately 50% of mutant mice dying with hydrocephalus before adulthood, and males surviving to maturity were infertile due to impaired sperm motility in the original genetic background (C57/SV129) (Sapiro et al. 2002). This study revealed an abnormal axoneme ultrastructure in sperm of the Spag6-deficient mice (Sapiro et al. 2002). However, our subsequent studies demonstrated that the “9+2” array of the motile cilia in brain ependymal cells and trachea epithelial cells appeared to be grossly normal and that the hydrocephalus in the Spag6-deficient mice is due in part to the disruption of polarity of the basal bodies in addition to motility defects (Zhang et al. 2007). Disruption of Spag6 led to abnormalities in polarized cell morphology and distribution of α-tubulin and the planar cell polarity protein (Vangl2) in mouse tracheal epithelial cells (Teves et al. 2014). In addition, the mutant mice had fewer cilia in the trachea and ependymal epithelial cells (Teves et al. 2014), and also developed otitis media due to dysfunction of motile cilia in the epithelial cells in the middle ear (Li et al. 2014).

Besides its functions in cells with motile cilia, SPAG6 plays fundamental roles in cells without motile cilia. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from Spag6-deficient mice proliferated at a much slower rate than cells isolated from wild-type mice, and they had a larger surface area. The mutant cells had reduced migration, adhesion associated with a non-polarized F-actin distribution, fewer primary cilia, and reduced expression of acetylated tubulin. These abnormalities were rescued by restoration of SPAG6 expression in the Spag6-deficient MEFs (Li et al. 2015a). Recent studies demonstrated that the Spag6 gene is essential for the mechanosensory function of outer hair cells in the inner ear (Wang et al. 2015), and SPAG6 deficiency resulted in synapse disruption due to loss of centrosome polarization and actin clearance at the synaptic cleft, suggesting it regulates neuronal migration (Yan et al. 2015). Yan and colleagues discovered that SPAG6 not only mediates neuronal migration but also neurite branching and elongation (Yan et al. 2015).

Increasing evidence suggests that SPAG6 is relevant to cancer. Several studies demonstrated that SPAG6 gene expression was up-regulated in some primary cancers and cancer cell lines (Silina et al. 2011, Mulaw et al. 2012), and silencing SPAG6 expression by SPAG6-short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentivirus dramatically inhibited tumor growth and stimulated apoptosis in SKM-1 cells through the TRAIL signal pathway (Yang et al. 2015).

In view of the complex and novel functions of SPAG6, we reevaluated the mechanisms underlying male infertility in the Spag6-deficient mice, which was originally reported to be caused by reduced sperm motility (Sapiro et al. 2002). Given the abnormal testicular and epididymal sperm ultrastructure in the Spag6-deficient mice, we hypothesized that mouse SPAG6 also controls spermatogenesis. SPAG6 is found in multiple germ cell compartments, and we identified its binding partners with a yeast two-hybrid screen. These proteins carry out multiple functions, including maintaining the cytoskeletal system, vesicle transport, and acrosome biogenesis. Expression levels of some of these proteins were significantly reduced in the Spag6-deficient mice. We propose that SPAG6 functions as a chaperone protein that associates with other proteins to perform critical biologic functions in multiples steps in spermatogenesis. The present studies establish a platform to further investigate the roles of SPAG6 and its binding partners in spermatogenesis regulation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free stage and approved by Virginia Commonwealth University's Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (protocol AD10000167) in accordance with Federal and local regulations regarding the use of non-primate vertebrates in scientific research.

Mice used in the study

Spag6 and Spag16L knockout mice were generated at the University of Pennsylvania by Dr. Jerome F. Strauss, III (Sapiro et al. 2002, Zhang et al. 2006). The original genetic background of the Spag6 knockout mice was C57BL/6/sv129. The Spag6-deficient mouse line has been maintained through breeding of heterozygous males and females. Spink2 knockout mice were generated by Drs. Pierre F. Ray and Christophe Arnoult (Kherraf et al. 2017).

Histological analysis

To analyze testicular integrity, mouse testes were fixed by immersion in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 5 μm slices. Samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard procedures. Histology of testes was examined a BX51 Olympus microscope (Olympus Corp., Melville, NY), and photographs were taken with the ProgRes C14 camera (Jenoptik Laser, Germany).

Yeast two-hybrid experiments

The eight armadillo repeats of the SPAG6 coding sequence was cloned into the EcoR1/BamH1 sites of pGBKT7, which was used to screen a Mate & Plate™ Library – Universal Mouse (Normalized) (Clontech, Cat#: 630482) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two rounds of screens were performed. For the first round, a more stringent protocol was used, and the yeast was grown on plates lacking four amino acids (-Ade-His-Leu-Trp). Given that only about fifty yeast clones grew in the first round of the screen, a second screen was conducted with a less stringent protocol, and the yeast were grown on plates lacking three amino acids (-His-Leu-Trp). For direct yeast two-hybrid assays, the coding sequences of the indicated genes were amplified by RT-PCR using primers listed in Table 1 and cloned into a pGAD-T7 vector. The yeast was transformed with the indicated plasmids using the Matchmaker™ Yeast Transformation System 2 (Clontech, Cat#: 630439). Two plasmids containing simian virus (SV) 40 large T antigen in pGADT7 and p53 in pGBKT7 were co-transformed into AH109 as a positive control. Full length and truncated mouse Snapin clones in the pGAD-T7 vector were described in Wolff et al (2006) (Wolff et al. 2006).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primer Name | Sequences |

|---|---|

| Actr2 | Forward: 5-’GAATTCATGGACAGCCAGGGCAGGAAG-3’ Reverse: 5’-GGATCCCTCGAACAGTTACACCAAGTTTC-3’ |

| Arpc3 | Forward: 5’-GAATTCATGCCGGCATACCACTCTTCTC-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCCTGCCCAGGCCCCGAAAGACTC-3’ |

| BBS4 | Forward: 5’-GAATTCATGGCTGAAGTGAAGCTTGGGATG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCTTTTTCTTTCTTTTGTTCTGATGC-3’ |

| COPS5 | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGGCAGCTTCCGGGAGTGG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCAGCAACGTTAATCTGATTAAAC-3’ |

| MGP | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGAAGAGCCTGCTCCCTCTG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCATATTTGGCTCCTCGGCGCTGC-3’ |

| Tac1 | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGAAAATCCTCGTGGCCGTG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCTTTACGTCTTCTTTCGTAGTTC-3’ |

| Tcte3 | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGGAGCGGCGAGGCCGAATG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCTTCACAATAGAGAGCAAACACC-3’ |

| Spink2 | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGCTGAGACTGGTGCTGTTG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCGCATGGCTCGTCTTTGATGAT-3’ |

| Dazl | Forward:5’-GAATTCATGTCTGCCACAACTTCTGAG-3’ Reverse:5’-GGATCCCGCAGAGATGATCAGATTTAAGC-3’ |

Cell culture and transient transfection

COS-1 and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in DMEM or DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C. The cells were transfected with indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine™2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After transfection, the cells were processed either for immunofluorescence analysis, Western blot, or co-immunoprecipitation.

Western blot analysis

Mouse testicular samples were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer and protein concentration was measured using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein were heated to 95°C in sample buffer for 5 min, resolved in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After blocking in TBS-T buffer (Tris-buffered saline solution containing 5% non-fat dry and 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with indicated antibodies (Snapin: 1:1000, Proteintech, Cat number: 10055-1-AP; SPINK2 (from rabbit): 1:1000, from Dr. Chunghee Cho; SPAG16L (from rabbit): 1:1000, generated by our own laboratory; COPS5: 1:1000, Sigma, Cat number: J3020) or rabbit β-actin (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. After being excessively washed with TBS-T, the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000 dilution) at room temperature for 1 h. The proteins were detected using SuperSignal™ West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Isolation of spermatogenic cells and immunofluorescence (IF) analysis

Spermatogenic cells were prepared as previously described (Li et al. 2015b). For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) at 37°C for 5 min, washed with PBS three times, and blocked with 10 % goat serum in PBS at room temperature for 1 hr. After incubation with the indicated primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, the cells were washed with PBS three times and incubated with Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody for 1 h. The slides were washed with PBS and mounted in VectaMount with DAPI (Vector Labs) and sealed with a cover slip. Images were captured by confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of testis sections

Testes from adult wild-type and age-matched Spag6 knockout mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), and 5 μm paraffin sections were made. The sections were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Following secondary antibody incubation, the slides were washed three times with PBS, and mounted using VectaMount withDAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA), and sealed with a cover slip. Images were captured by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 700). Some sections were stained with an acrosome marker, peanut-lectin (Invitrogen, Cat number: L21409) (Mortimer et al. 1990). Briefly, after the sections were stained with secondary antibody, the sections were washed three times with PBS, and incubated with peanut-lectin (2-10 μg/ml final concentration) at room temperature for 15 min, washed three times again with PBS, mounted with VectaMount, and sealed with a cover slip. Images were captured by confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

Mammalian expression constructs, confocal microscopy and co-immunoprecipitation assays

Total RNA from mouse testes was extracted using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen) and reversed transcribed to cDNA using the RevertAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Coding sequences of indicated genes were amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table 1 and cloned into pEGFP-N2 or pCS3+FLT, respectively. The indicated plasmids were co-transfected into COS-1 cells and co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed following previously described methods (Zhang et al. 2009). Briefly, the supernatant of cell lysates was pre-cleaned with protein A beads at 4°C for 30 min and the pre-cleared extract was then incubated with the indicated antibodies or preimmune serum as a negative control at 4°C for 2 h. The mixture was then incubated with protein A beads at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed with immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, proteinase inhibitor) three times. The collected samples were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies.

To examine colocalization of SPAG6 and its binding partners in mammalian cells, CHO cells were transfected with express mouse SPAG6 and GFP-tagged binding partners, and the cells were immunostained with a specific primary antibody against SPAG6, and a Cyc3-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to visualize SPAG6 localization. Images were captured by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Leica TCS-SP2 AOBS).

Results

SPAG6 is present in cytoplasmic vesicles in spermatocytes, and migrates to the acrosome and manchette in spermatids

In order to explore the function of SPAG6 in germ cell development, we examined its expression level during the first wave of spermatogenesis and localization in male germ cells isolated from adult wild-type mice. The 56 kDa SPAG6 was detected from day 8 after birth, and its level was increased at day 16 (Fig. 1A). Specific signals were detected in vesicles in spermatocytes (Fig. 1Ba). In round spermatids, SPAG6 is present in the acrosome as shown by its colocalization with the acrosome marker, peanut-lectin (Fig. 1Bb, c, e). In elongating spermatids, SPAG6 is in the acrosome and the manchette, as shown by its co-localization with α-tubulin, a marker for the manchette (Fig. 1Bd, e). The localizations in vivo suggest a role for SPAG6 in vesicle trafficking, acrosome biogenesis, and cargo transport along the manchette.

Figure 1. Examination of SPAG6 expression level and localization in the testes of wild-type mice.

(A) Analysis of testicular SPAG6 expression during the first wave of spermatogenesis in wild-type mice. a. A representative western blot result showing SPAG6 expression; b. Quantitative analysis of relative SPAG6 expression normalized by β-actin. n=3. Notice that the level was significantly increased at day 16 after birth.

(B) Localization of SPAG6 in male germ cells. Mixed germ cells were double-stained with the indicated antibodies. SPAG6 was present as vesicles in the spermatocytes (white arrows in a), and was localized in the acrosome in round and elongating spermatids (white dashed arrows in b, c, e) and manchette of the elongating spermatids (white arrow heads in d, e). DNA was stained with DAPI.

Morphological defects in spermatogenesis in Spag6-deficient mice

In global Spag6-deficient mice, we found that testicular and epididymal sperm had disrupted ultrastructure (Sapiro et al. 2002). To further evaluate the process of spermatogenesis in the global Spag6-deficient mice, testicular histology was examined throughout the first wave of spermatogenesis. From day 16 after birth, Spag6-deficient mice showed a delay in germ cell development. At day 42 after birth, well-developed sperm were discovered in the lumen of the seminiferous tubules of the wild-type mice, but fewer sperm were found in the Spag6-deficient mice (Fig. 2), indicating that spermatogenesis was affected at least from the meiosis phase. The normal histological features of Sertoli cells and epididymal epithelial cells in the Spag6-deficient mice indicate adequate gonadotropin support.

Figure 2. Analysis of testis and epididymis histology of wild-type and Spag6-deficient mice.

(A) Representative H&E staining images of testes from wild-type and Spag6-deficient mice during the first wave of spermatogenesis. Notice that there was a significant delay in germ cell development from day 16 after birth.

(B) Representative H&E staining images of the epididymis of a 35 day wild-type mouse and its two Spag6 knockout littermates. Notice that the lumen is filled with sperm (arrows) in the wild-type mouse; however, only few cells were present in the two knockout mice (dashed arrows).

SPAG6 associates with multiple partners

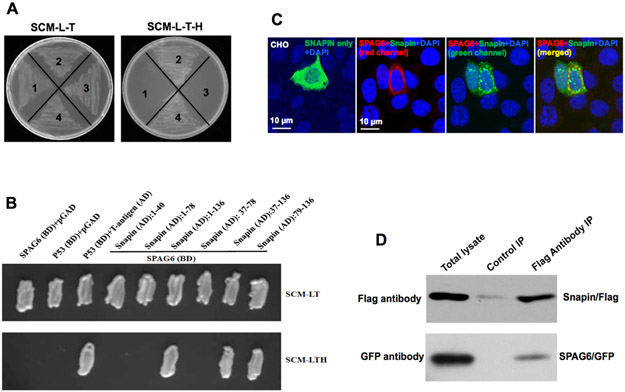

SPAG6 contains eight contiguous armadillo repeats, a structural feature mediating protein-protein interaction (Sapiro et al. 2000, Tewari et al. 2010). To gain insights into the mechanisms by which SPAG6 influences spermatogenesis and other biologic functions, the armadillo repeats were used as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen. Two rounds of screening were conducted. The first screen was carried out using a stringent protocol, and the yeast were grown on plates lacking four amino acids (-Ade-His-Leu-Trp). Only about forty yeast clones grew on the selection plates. Plasmid DNA was isolated from these clones, and potential binding partners were identified after sequencing the recovered plasmid DNA. The candidate partner genes are listed in the Supplementary Table 1. Given the low number of the candidate genes using the stringent protocol, we decided to perform another screen using a less stringent protocol, and the yeast were grown on plates lacking three amino acids (-His-Leu-Trp). More candidate interactome genes were identified, and these genes are listed in the Supplementary Table 2. It should be noted that interacting genes from the second screen included genes from the first screen. In both screens, a number of proteins appeared multiple times, including Snapin, COPS5, SPINK2, TAC1 and Msn. Among them, Snapin was the most frequently identified binding partner in both screens. Therefore, we confirmed interaction between SPAG6 and Snapin. Direct yeast two-hybrid assays revealed that yeast co-transformed with the SPAG6/Snapin pair grew on both selection and non-selection plates, indicating that the two proteins interact in yeast (Fig. 3A). A series of truncated Snapin yeast expression constructs were available in the laboratory, including Snapin1-40, Snapin1-78, Snapin1-136, Snapin37-78, Snapin37-136, and Snapin79-136. We next examined the Snapin domains that are able to interact with SPAG6. Pairs of SPAG6 and the truncated Snapin yeast expression plasmids were co-transformed into AH109 yeast, and growth of the transformed yeast was assayed on selection plates. Besides the full-length Snapin construct, yeast co-transformed with SPAG6 and the C-terminus of Snapin (Snapin37-136, Snapin79-136) grew on the selection plates (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. SPAG6 interacts with Snapin.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay to examine the interaction of SPAG6 and full-length Snapin in yeast. Yeast AH109 was transformed with the indicated plasmids and then grew on non-selective and selective media, respectively. 1: Spag6/pGBKT7 and pGADT7; 2: Spag6/pGBKT7 and Snapin/pGADT7; 3: p53/pGBKT7 and pGADT7; 4: p53/pGBKT7 and IgT/pGADT7; (B) Mapping the Snapin domain that mediates interaction with SPAG6 by direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Notice that SPAG6 interacted with the C-terminal domain of Snapin; (C) Colocalization of SPAG6 and Snapin. CHO cells were co-transfected with SPAG6/pTarget and Snapin/pEGFP-N2. The CHO cells were immunostained with a specific antibody against SPAG6. Notice that Snapin/GFP only was localized in the cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, Snapin partially colocalizes with SPAG6. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of SPAG6 with SNAPIN. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with Spag6/GFP and Snapin/Flag. The cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and then subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies. The cell lysate immunoprecipitated with a mouse normal IgG was used as a control.

The interaction between SPAG6 and Snapin was further confirmed in transfected mammalian cells. In CHO cells, Snapin was localized in the cytoplasm. However, when Snapin and SPAG6 were co-expressed, SPAG6 recruited Snapin to specific regions, and the two proteins were partially colocalized (Fig. 3C). In addition, we transfected COS-1 cells with SPAG6/GFP and Snapin/Flag expression plasmids and conducted a co-immunoprecipitation assay. The Flag antibody pulled down both Flag-tagged Snapin and SPAG6, suggesting an interaction between two proteins (Fig. 3D).

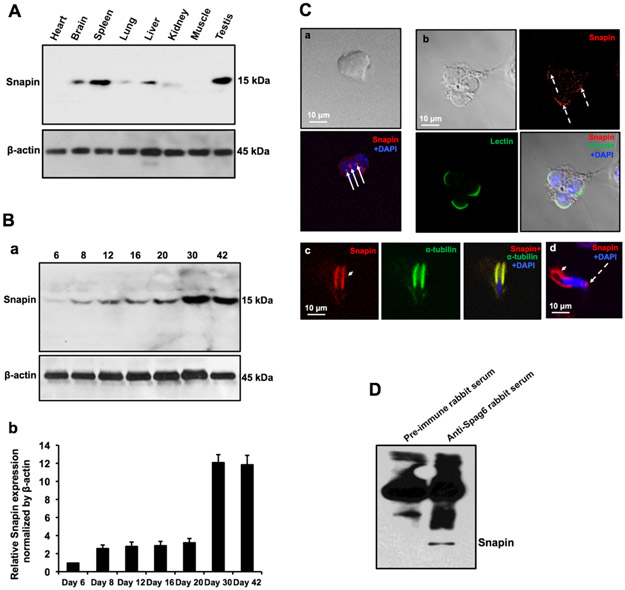

Snapin protein expression and localization in male germ cells of wild-type mice.

Western blot analysis showed that the Snapin expression level is the highest in the mouse testis among the tissues analyzed (Fig. 4A). Testicular Snapin expression during the first wave of spermatogenesis was also examined. The protein was initially detected at day 6 and its expression dramatically increased at day 30 (Fig. 4B), consistent with a role in spermiogenesis. Immunofluorescence staining showed that Snapin was present in vesicles in spermatocytes (Fig. 4Ca) and highly concentrated in the acrosomal region of round spermatids (Fig. 4Cb), and the manchette of elongating spermatids (Fig. 4Cc). The cellular localizations of Snapin are almost identical to that of SPAG6 (Fig. 2), which supports the notion that Snapin and SPAG6 are in the same complex. The interaction between SPAG6 and Snapin was further investigated in vivo. Testis extract was subjected to a pull-down assay with anti-SPAG6 antibody, and presence of Snapin in the SPAG6 complex was examined by Western blotting using the specific anti-Snapin antibody. The SPAG6 antibody pulled down Snapin (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Expression and localization of Snapin in male germ cells of wild type mice.

(A) Snapin expression in the indicated mouse tissues. The protein was predominantly expressed in the testis. (B) Testicular Snapin expression during the first wave of spermatogenesis. Its expression increased at day 30 after birth when germ cells undergo spermiogenesis. a. A Representative western blot result; b. Quantitative analysis of relative Snapin expression normalized by β-actin. n=3; (C) Examination of Snapin localization in male germ cells by immunofluorescence staining. Snapin signals (red signals pointd by white arrows) were detected in spermatocytes (a), the acrosomal region of round spermatids (dashed white arrows in b and d) and the manchette of elongating spermatids (white arrow heads in c and d). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). (D) Examination of SPAG6 and Snapin interaction in vivo by co-immunoprecipitation assay. The testicular extract was immunoprecipitated using a specific anti-SPAG6 antibody, and Western blotting was conducted using a specific anti-Snapin antibody. The Snapin was pulled down by the SPAG6 antibody.

SPAG6 also associates with some other proteins with distinct functions

Besides Snapin, several other proteins also appeared multiple times in the yeast two-hybrid screens. In addition, given its localization in male germ cells and mammalian cells when over-expressed in vitro, we hypothesized that SPAG6 is involved in vesicle/cargo transport. We next chose the proteins that appeared multiple times or whose functions are related to the predicted roles of SPAG6 and further tested their interaction. These proteins include COP9 (constitutive photomorphogenic) homolog, subunit 5 (Arabidopsis thaliana) (COPS5), serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type (SPINK2), t-complex-associated testis expressed 3 (TCTE3), tachykinin 1 (TAC1), Bardest-Biedl syndrome 4 (BBS4), moesin (Msn), deleted in azoospermia-like (DAZL), ARP2 actin-related protein 2(ACTR2), and actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3 (ARPC3).

We first examined interactions between SPAG6 and COSP5 in vitro. Direct yeast two-hybrid assays revealed that the two proteins interact in yeast (Fig. 5A). In transfected CHO cells, COPS5 is present in the entire cytoplasm. However, when it was co-expressed with SPAG6, the two proteins appeared to be more concentrated in specific regions in the vicinity of the nuclear membrane (Fig. 5B). Co-immunoprecipitation assays confirmed the interaction of the two proteins in transfected COS-1 cells. When the COS-1 cells were co-transfected with COPS5 and SPAG6 expression plasmids, the anti-Flag antibody pulled-down both SPAG6/Flag and COPS5/GFP protein (Fig 5C).

Figure 5. Interaction between SPAG6 and COPS5.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with the SPAG6/COPS5 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and COPS5 interact in yeast. 1: AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+COPS5/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and COPS5 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with Cops5/pEGFP-N2 (panels a & b) alone, or along with SPAG6/pTarget (c-j). The CHO cells were immunostained with anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Notice that COPS5/GFP alone was present in the whole cell bodies evenly. However, when SPAG6 was co-expressed, both proteins appeared to be highly concentrated in the specific region around the nucleus surface (white arrows) and the two proteins are colocalized. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of SPAG6 with COPS5. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with SPAG6/Flag and COPS5/GFP. The cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and then subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies. The cell lysate immunoprecipitated with a mouse normal IgG was used as a control.

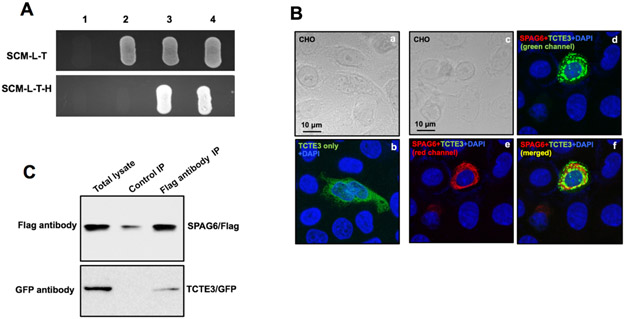

Similar experiments were conducted to confirm interactions between SPAG6 and SPINK2 (Fig. 6), and SPAG6 and TCTE3 (Fig.7). The interaction between SPAG6 with TAC1, moesin, BBS4, DAZL, MGP, ACTR2 and ARPC3 were also examined (Supplementary Figure 1 to 6).

Figure 6. Interaction between SPAG6 and SPINK2.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/SPINK2 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and SPINK2 interact in yeast. 1: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+SPINK2/pGADT7; 3: p53/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and SPINK2 in transfected CHO cells. Notice that SPINK2 only is expressed in the cytoplasm. SPAG6 recruits SPINK2 to the region where SPAG6 locates. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation assay. SPAG6/GFP and SPINK2/Flag plasmids were co-transfected into COS-1 cells, and the Flag antibody pulled down both SPINK2 and SPAG6. The cell lysate immunoprecipitated with a mouse normal IgG was used as a control

Figure 7. Interaction between SPAG6 and TCTE3.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/TCTE3 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and TAC1 interact in yeast. 1: AH109 only; SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+TCTE3/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and TCTE3 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were cotransfected with TCTE3/pEGFP-N2 (panels a & b) alone, or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (panels c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). TCTE3/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the TCTE3/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colcalized. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of SPAG6 with TCTE3. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with SPAG6/Flag and TCTE3/GFP. The cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and then subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies.

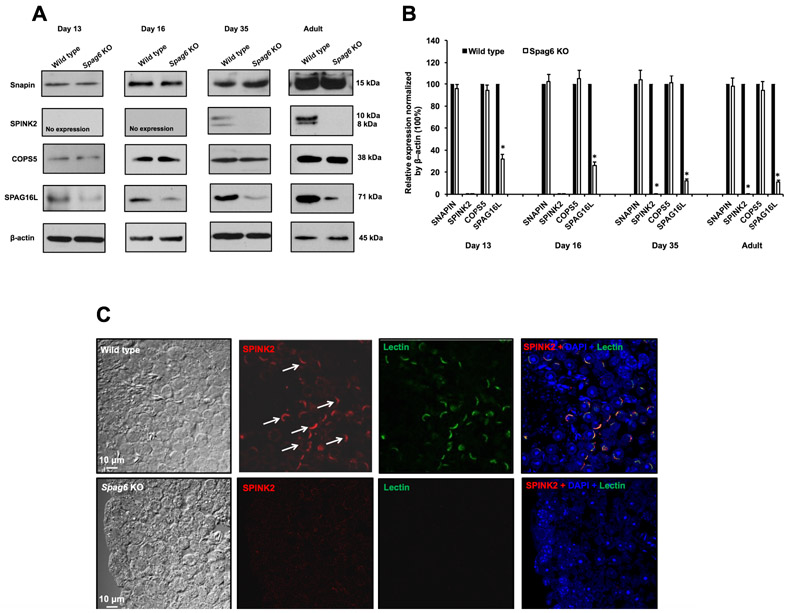

Testicular expression of selected SPAG6 binding partners in the Spag6-deficient mice

Snapin, COPS5, and SPINK2 were the top three binding partners of SPAG6 in the yeast two-hybrid screens. Their testicular expression levels were compared between Spag6-deficient mice and wild-type littermates in younger mice and adult mice. Western blot analysis revealed that there was no difference in Snapin and COPS5 expression levels between wild-type and Spag6-deficient mice, either in younger mice or adult mice (Fig. 8A, B). However, SPINK2 was absent in the Spag6-deficient mice in all the ages examined. The localization of these proteins was further investigated in testis sections from adult wild-type and Spag6-deficient mice. Even though the antibodies against Snapin and COPS5 worked for Western blotting, no specific signals were detected in testis sections from both wild-type mice and Spag6-deficient mice. As reported recently, SPINK2 was localized in the acrosome in the wild-type mice. Even though testicular SPINK2 was not detected in the Spag6 knockout mice by Western blot analysis, and SPINK2 signal was absent in the Spag6-deficient mice (Fig. 8C) and Spink2 knockout mice (Supplementary Figure 7) when a recommended concentration of the anti-SPINK2 antibody was used, a trace amount of SPINK2 was observed in the Spag6-deficient mice, but not in the Spink2 knockout mice when a high concentration of the anti-SPINK2 antibody was used (Supplementary Figure 8). Similarly, the signal for a marker for the acrosome, peanut-lectin was also absent in the Spag6-deficient mice when a 2 μg/ml final concentration was used, but a weak signal was observed when a 10 μg/ml final concentration was used (Supplementary Figure 8).

Figure 8. Expression of SPAG6 binding partners in the testis of Spag6-deficient mice.

(A) Representative Western blot results using the indicated antibodies. Notice that there was no difference in Snapin and COPS5 expression levels between wild type and Spag6 knockout mice in either younger mice or adult mice. However, SPINK2 protein was missing in all ages of the Spag6-deficient mice analyzed; and expression levels of SPAG16L, a previously identified SPAG6 binding partner, were also reduced in these Spag6-deficient mice.

(B) Statistical analysis of relative expression of the indicated proteins normalized by β-actin. There was no difference in expression levels of Snapin and COPS5 between the controls and the Spag6 KO mice. SPAG16L expression levels were significantly reduced in the KO at all ages analyzed.

(C) Examination of localization of SPAG6 binding partners in the testis seminiferous tubules of wild type and Spag6-deficient mice. SPINK2 was present in the acrosome of the wild-type mice (white arrows); however, no specific SPINK2 (1: 300 dilution) and Lectin (2 μg/ml of final concentration) signals were detected in the Spag6-deficient mice.

SPAG16L, a previously identified SPAG6 binding partner, is absent in the manchette of Spag6 knockout mice

We previously reported that another central apparatus protein, SPAG16L, associates with SPAG6 and its testicular expression was dramatically reduced in the Spag6-deficient mice (Zhang et al. 2002). Even though SPAG16L was not identified in our yeast two-hybrid screen, we examined its expression and localization in Spag6 knockout mice. The testicular SPAG16L expression level was not only significantly reduced in the adult Spag6-deficient mice, its expression was also reduced in younger mice (Fig. 8A, B). We have previously shown that SPAG16L is present in the cytoplasm of round spermatids and migrates to the manchette of the elongating spermatids (Li et al. 2015b, Zhang et al. 2016). In the Spag6-deficient mice, SPAG16L is still present in the cytoplasm of round spermatids, but it is absent from the manchette (Fig. 9A). SPAG6 expression was examined in the Spag16L–deficient mice. There was no difference in the testicular expression of SPAG6 between the wild-type and Spag16L-deficient mice (Fig. 9B). Immunofluorescence staining showed that SPAG6 is still present in the manchette of the elongating spermatids of the Spag16L-deficient mice (Fig. 9C). These findings suggest that SPAG6 is the factor controlling SPAG16L localization. Consistent with the Western blot result, SPAG16L signal in the testis section was also reduced in the Spag6-deficient mice (Supplementary Figure 9).

Figure 9. SPAG16L expression and localization in the Spag6 knockout mice.

(A) Examination of SPAG16L localization in the isolated germ cells from Spag6 knockout mice by immunofluorescence staining. Notice that SPAG16L was present in the manchette of the elongating spermatids of wild-type mice (white arrow). However, it was missing from the manchette of the elongating spermatids from the Spag6 knockout mice.

(B) Analysis of testicular SPAG6 expression level in the Spag16L knockout mice. Notice that there was no difference in SPAG6 expression level between the wild-type and the Spag16L knockout mice.

(C) Examination of SPAG6 localization in the isolated germ cells from Spag16L knockout mice by immunofluorescence staining. Notice that SPAG6 was still present in the manchette of the elongating spermatids from the Spag16L knockout mice (white arrow).

Discussion

The ubiquitous expression of Spag6 in mammalian tissues harboring ciliated cells, led to further exploration of the function of SPAG6, revealing that this protein is involved in diverse cellular processes, including ciliogenesis, cilia polarity, cell proliferation, division, differentiation and migration (Li et al. 2014, Teves et al. 2014, Li et al. 2015a, Yan et al. 2015, Hu et al. 2016). Due to significantly reduced sperm numbers and disrupted sperm ultrastructure, we hypothesized that SPAG6 also controls spermatogenesis besides regulating sperm motility. We found that endogenous SPAG6 is located in vesicles in spermatocytes, in the acrosome of round/elongating spermatids, and the manchette of elongating spermatids, unique structures essential for spermiogenesis (Hermo et al. 2010, Lehti & Sironen 2016). The localization of SPAG6 in multiple male germ cell compartments in wild-type testis provides a framework for understanding the morphological abnormalities that we detected at the light microscope level in SPAG6-deficient mice during the first wave of spermatogenesis. These abnormalities appeared in the seminiferous tubules from day 16 after birth. This observation is consistent with the finding that SPAG6 is initially expressed earlier, but the protein/mRNA levels are increased at postnatal day 16 and accumulate afterward (Horowitz et al. 2005).

It is unlikely that the developmental delay of germ cells in the first wave of spermatogenesis was due to abnormalities in gonadotropin secretion in surviving mice. In our original studies, sex dependent organs were weighed, and they were comparable in weight and histology in knockout and wild-type mice, suggesting that testosterone production was not affected (Sapiro et al. 2002). In the present study, the normal histological features of Sertoli cells and epididymal epithelial cells in the Spag6-deficient mice indicate adequate gonadotropin support. Thus, we believe that the spermatogenesis defects in the Spag6 knockout mice are largely due to multiple functions of SPAG6 in the regulation of spermatogenesis. This is supported by the fact that multiple compartments are affected by SPAG6 and SPAG6 associates with multiple proteins that are essential for germ cell development.

It has been shown that mammalian round spermatids have a cytoplasmic microtubule network, and a bundle of microtubules is concentrated close to the acrosome (Moreno & Schatten 2000). Depolymerization of microtubules by nocodazole resulted in fragmentation of the acrosome in round spermatids, and structural alteration of microtubules by a mutation in mice caused abnormal placement of acrosomal proteins (Moreno et al. 2006). Our previous results showed that SPAG6 interacts with microtubules and regulates their cytoskeletal arrangement through acetylation of tubulin (Zhang et al. 2005, Li et al. 2015a). Localization of SPAG6 in the acrosomal region and microtubule-based manchette of spermatids suggests that this protein might impact the structural integrity and/or functions of the acrosome and manchette through post-translational modification of microtubules. The reduced sperm count in Spag6 knockout mice could be partially explained by the dysfunction of acrosome and/or manchette.

As SPAG6 has eight contiguous armadillo repeats that mediate protein-protein interaction (Sapiro et al. 2000, Zhang et al. 2005, Tewari et al. 2010), it is likely that this protein regulates spermatogenesis via complexes with other essential proteins. Snapin was identified as the most frequent binding partner when SPAG6 was used as bait in yeast two-hybrid assays. The interaction between SPAG6 and Snapin was verified by direct yeast two-hybrid assays, colocalization, and co-immunoprecipitation assays. Snapin was first identified as an interacting partner for synaptosome-associated protein-25 (SNAP-25), a subunit of the SNARE core complex (Ilardi et al. 1999). Due to the presence of a coiled-coil domain responsible for protein-protein interaction, studies of Snapin function in the formation of neurons indicate that it acts as an adaptor for recruitment of critical proteins, and is involved in long distance cargo transport through vesicle trafficking (Zhou et al. 2012, Quintero et al. 2013, Ye & Cai 2014). The manchette is a transient structure surrounding the elongating spermatid head and some structural proteins of sperm are transported through the manchette to the basal body and the assembly site in the flagellum (Lehti & Sironen 2016). Direct interaction between Snapin and SPAG6, and colocalization of these proteins in the acrosome and manchette suggest that SPAG6 might be transported to these cellular organelles with the aid of Snapin during spermatogenesis, or the other way round. The pattern of SPAG6 localization strongly suggests its role in cargo transport. This is also supported by our previous findings. Another two central apparatus proteins, SPAG16L and SPAG17 are SPAG6 binding partners, and both SPAG16L and the 28 kDa SPAG17 are missing from the sperm of the Spag6-deficient mice (Zhang et al. 2002, Zhang et al. 2005). SPAG16L is also present in the manchette of the elongating spermatids (Li et al. 2015b), and our recent studies revealed that SPAG17 is also present in the manchette (unpublished observations). Thus, SPAG6 might be involved in transporting these two proteins along the manchette, a notion that is supported by the fact that SPAG16L is missing from the manchette of the elongating spermatids of Spag6-deficient mice.

Given that BBS4 is a SPAG6 binding partner and is a component of BBSomes that associate with the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system for ciliogenesis (Lechtreck et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2012), it is possible that SPAG6 also plays a role in IFT in sperm flagella formation. This idea is supported by the fact that IFT140, an IFT component was identified in our yeast two-hybrid screen (Supplementary Table 2). Using a conditional knockout strategy, our laboratory showed that several IFT components are essential for spermatogenesis and sperm formation (Zhang et al. 2016, Liu et al. 2017).

SPINK2 is exclusively expressed in the mouse testis and acrosome of round spermatids and mature sperm, and was shown to efficiently inhibits acrosomal proteases and in particularthe acrosin (ACR) (Lee et al. 2011, Kherraf et al. 2017). Knockout of Spink2 in mice resulted in loss of the acrosome and developmental arrest and death of germ cells at the round-spermatid stage (Lee et al. 2011, Kherraf et al. 2017). Male germ cells loss was shown to be associated with the inability of Spink2-deficient mice to inhibit ACR during its transit from the Golgi apparatus to the acrosome during acrosome formation in round spermatids (Kherraf et al., 2017). SPAG6 likely stabilizes SPINK2 in vivo, as SPINK2 is missing in the Spag6-deficient mice. As Spink2−/− animals present azoospermia due to post meiotic arrest, we can postulate that SPINK2 loss in Spag6−/− males plays an important role in the germ cell loss observed in these mice. It can however not be excluded that the very low levels of SPINK2 observed Spag6−/− testis are secondary to the low number of round spermatids and spermatozoa. In addition, a testicular gene, Tcte3, which encodes a putative light chain of the outer dynein arm in the axoneme of flagella (Patel-King et al. 1997, Rashid et al. 2010), was identified as a SPAG6-binding partner. Even though the axoneme of Tcte3-deficient mice flagella remained grossly intact, loss of Tcte3 caused apoptosis of male germ cells at the prophase I stage (Rashid et al. 2010). It has been reported that SPAG6 is associated with human malignancies and knockdown of SPAG6 by RNAi inhibited cell proliferation and stimulated apoptosis of hematologic malignant cell lines (Silina et al. 2011, Yang et al. 2015). Interaction of SPAG6 with SPINK2 and TCTE3 suggests that these proteins might form a complex, with SPAG6 serving as a bridge. The protein complex might cooperatively regulate germ cell survival via mediation of cellular apoptosis in the late stage of spermatogenesis.

COPS5 is another major binding partner. It is a subunit of the COP9 signalosome complex (CSN), a complex involved in various cellular and developmental processes (Kato & Yoneda-Kato 2009). The CSN complex is an essential regulator of the ubiquitin (Ubl) conjugation pathway, deubiquitinylation of IkappaBalpha, phosphorylation of p53/TP53, c-jun/JUN, ITPK1 and IRF8, possibly via its association with CK2 and PKD kinases(Cohen et al. 2000, Uhle et al. 2003, Schweitzer et al. 2007, Kato & Yoneda-Kato 2009). It has been shown that COPS5 interacts with Fank1, a gene highly expressed in testis that functions as an anti-apoptotic protein that stimulates the activator protein 1 (AP-1) pathway (Wang et al. 2011). Thus, SPAG6 may modulate the anti-apoptotic function through interactions with COPS5. SPAG6 may also be involved in the ubiquitin conjugation pathway in male germ cells.

About 50% Spag6-deficient mice survived to adult in the original genetic background. However, the percentage dramatically dropped in the past 15 years, and very few homozygous mutant mice survive to adult now. Therefore, we were not able to analyze Snapin and COPS5 localization in the isolated germ cells from adult Spag6 knockout mice. A conditional knockout model needs to be generated so that Spag6 gene can be disrupted specifically in male germ cells, and their localizations can be examined.

Sperm flagellar 2 (SPEF2), even though not investigated in this study, was picked up in our yeast two-hybrid screen. SPEF2 has a similar localization as SPAG6 in male germ cells (Sironen et al. 2010), and disruption of Spef2 gene resulted in similar phenotypes as Spag6 knockout mice (Sironen et al. 2011, Lehti et al. 2017) Thus, SPEF2 might also be a component of the SPAG6 interactome.

Given that the library used for the screen was not testis-specific, but a normalized library, the binding partners identified in our screen do not necessarily play roles only in male germ cells, but possibly also in other somatic cells/tissues. For example, TAC1 is thought to function as a neurotransmitter that interacts with nerve receptors and smooth muscle cells (Shanley et al. 2011, Lin et al. 2012), and studies in our laboratory and others revealed that SPAG6 does play a role in neuron system (Wang et al. 2015, Yan et al. 2015, Hu et al. 2016). MGP is member of Gla-containing proteins that have high-affinity binding to calcium ions, and act as inhibitors of vascular calcification and plays a role in bone organization (Zebboudj et al. 2002, Vassalle & Iervasi 2014). The reduced bone density (unpublished observation) and smaller size of the Spag6-deficient mice strongly suggests a role of SPAG6 in bone development. Moreover, a number of other phenotypes have been reported in the Spag6-deficient mice (Li et al. 2014, Cooley et al. 2016).

In addition, some proteins related to cytoskeleton function were also identified, including moesin, ARP2 and ARPC3. ARP2 and ARPC3 are subunits of a ARP2/3 complex that are key factors for dendritic nucleation and organization of existing actin filaments (Svitkina & Borisy 1999). The ARP2/3 complex has been shown to play an important role in diverse cellular processes including cell migration and adhesion (May et al. 1999, Bailly et al. 2001, Rogers et al. 2003, Swaney & Li 2016). Our previous study showed that disruption of SPAG6 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) led to reduced cell motility and adhesion ability. Enrichment of F-actin at the leading edge of cells was not observed and generation of filopodia was also inhibited in Spag6-deficient MEFs (Li et al. 2015a). Thus, we expected that in the Spag6 knockout mice, primordial germ cells (PGCs) migration might be affected due to disrupted cytoskeleton system, and this may also be one of the factors that cause impaired spermatogenesis and male infertility in the Spag6-deficient mice.

In summary, our studies suggest that SPAG6, originally thought to only play a role as a component of the central apparatus in the axoneme of motile cilia/flagella, is essential for multiple processes involved in spermatogenesis by forming protein complexes with a number of different partners.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Interaction between SPAG6 and TAC1.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/TAC1 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and TAC1 interact in yeast. 1. AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+TAC1/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and TAC1 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with TAC1/pEGFP-N2 (panels a & b) alone or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (panels c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). TAC1/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the TAC1/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S2. Interaction between SPAG6 and Moesin.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/Moesin pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and TAC1 interact in yeast. 1. AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+moesin/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and Moesin in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were cotransfected with Moesin/pEGFP-N2 alone (a), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (b-d). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Moesin/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the Moesin/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S3. Interaction between SPAG6 and BBS4.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/BBS4 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and BBS4 interact in yeast. 1: AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+BBS4/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Co-localization of SPAG6 and BBS4 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with BBS4/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). BBS4/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the BBS4/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were co-localized.

Figure S4. Interaction between SPAG6 and DAZL in yeast.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/DAZL pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and DAZL interact in yeast. 1: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+DAZL/pGADT7; 3: p53/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and DAZL in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with DAZL/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). DAZL/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the DAZL/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S5. Interaction between SPAG6 and MGP in yeast.

Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/MGP pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and MGP interact in yeast. 1: SPAG6/pGBK-T7+pGAD-T7; 2: SPAG6/pGBK-T7+MGP/pGAD-T7; 3: p53/pGBK-T7+pGAD-T7; 4: p53/pGBK-T7+IgT/pGAD-T7. 5: pGAD-T7; 6: MGP/pGAD-T7; 7: pGAD-T7-lgT.

Figure S6. Interaction between SPAG6 and ACTR2 (or ARPC3) in transfected CHO cells.

(A) CHO cells were co-transfected with ACTR2/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). ACTR2/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the ACTR2/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized. (B) Similar co-localization assays were performed to examine the interaction between SPAG6 and ARPC3.

Figure S7. Examination of SPINK2 localization in Spink2 knockout mice.

SPINK2 was co-localized with the acrosome marker, peanut lectin in the wild-type mouse (white arrows in the upper panel), but the signal was missing in the Spink2 knockout mouse (lower panel).

Figure S8. Examination of SPINK2 and acrosome in the testis seminiferous tubules of wild type and Spag6-deficient mice using high concentrations of antibody and peanut lectin. Weak SPINK2 (white arrows) and peanut lectin (white arrow heads) signals were present in the Spag6 knockout mice when a high concentration of antibodies (1:100 for SPINK2) and peanut lectin (10 μg/ml of lectin) were used.

Figure S9. Examination of SPAG16L expression in the testis section of the Spag6 knockout mice

Notice that strong SPAG16L signal was detected in spermatocytes and round spermatids of wild-type mice; however, the signal was dramatically reduced in the Spag6 knockout mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott C. Henderson for his assistance and the staff of the Microscopy Core Facility of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH grants HD076257, HD090306, Virginia Commonwealth University Presidential Research Incentive Program (PRIP) and Massey Cancer Award (to ZZ), Natural Science Foundation of China (81671514, 81571428), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2018CFB114, 2018CFA040), Deutsche Krebshilfe grants (10-1683-KN2 and 10-2237-KN3 to UK) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants (SFB1149, B04 to UK and MW). B.G.R was kindly supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported

References

- Bailly M, Ichetovkin I, Grant W, Zebda N, Machesky LM, Segall JE & Condeelis J 2001. The F-actin side binding activity of the Arp2/3 complex is essential for actin nucleation and lamellipod extension. Curr Biol 11 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branche C, Kohl L, Toutirais G, Buisson J, Cosson J & Bastin P 2006. Conserved and specific functions of axoneme components in trypanosome motility. J Cell Sci 119 3443–3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Azriel A, Cohen T, Meraro D, Hashmueli S, Bech-Otschir D, Kraft R, Dubiel W & Levi BZ 2000. Interaction between interferon consensus sequence-binding protein and COP9/signalosome subunit CSN2 (Trip15). A possible link between interferon regulatory factor signaling and the COP9/signalosome. J Biol Chem 275 39081–39089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley LF, El Shikh ME, Li W, Keim RC, Zhang Z, Strauss JF, Zhang Z & Conrad DH 2016. Impaired immunological synapse in sperm associated antigen 6 (SPAG6) deficient mice. Sci Rep 6 25840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG & Smith CE 2010. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells. Part 2: changes in spermatid organelles associated with development of spermatozoa. Microsc Res Tech 73 279–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz E, Zhang Z, Jones BH, Moss SB, Ho C, Wood JR, Wang X, Sammel MD & Strauss JF 3rd, 2005. Patterns of expression of sperm flagellar genes: early expression of genes encoding axonemal proteins during the spermatogenic cycle and shared features of promoters of genes encoding central apparatus proteins. Mol Hum Reprod 11 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House SA, Richter DJ, Pham JK & Dawson SC 2011. Giardia flagellar motility is not directly required to maintain attachment to surfaces. PLoS Pathog 7 e1002167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Yan R, Cheng X, Song L, Zhang W, Li K & Zhao S 2016. The function of sperm-associated antigen 6 in neuronal proliferation and differentiation. J Mol Histol 47 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilardi JM, Mochida S & Sheng ZH 1999. Snapin: a SNARE-associated protein implicated in synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci 2 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato JY & Yoneda-Kato N 2009. Mammalian COP9 signalosome. Genes Cells 14 12091225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kherraf ZE, Christou-Kent M, Karaouzene T, Amiri-Yekta A, Martinez G, Vargas AS, Lambert E, Borel C, Dorphin B, Aknin-Seifer I, et al. 2017. SPINK2 deficiency causes infertility by inducing sperm defects in heterozygotes and azoospermia in homozygotes. EMBO Mol Med. 9 1132–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck KF, Johnson EC, Sakai T, Cochran D, Ballif BA, Rush J, Pazour GJ, Ikebe M & Witman GB 2009. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii BBSome is an IFT cargo required for export of specific signaling proteins from flagella. J Cell Biol 187 1117–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Park I, Jin S, Choi H, Kwon JT, Kim J, Jeong J, Cho BN, Eddy EM & Cho C 2011. Impaired spermatogenesis and fertility in mice carrying a mutation in the Spink2 gene expressed predominantly in testes. J Biol Chem 286 29108–29117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti MS & Sironen A 2016. Formation and function of the manchette and flagellum during spermatogenesis. Reproduction 151 R43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehti MS, Zhang FP, Kotaja N & Sironen A 2017. SPEF2 functions in microtubule-mediated transport in elongating spermatids to ensure proper male germ cell differentiation. Development 144 2683–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Mukherjee A, Wu J, Zhang L, Teves ME, Li H, Nambiar S, Henderson SC, Horwitz AR, Strauss Iii JF, et al. 2015a. Sperm Associated Antigen 6 (SPAG6) Regulates Fibroblast Cell Growth, Morphology, Migration and Ciliogenesis. Sci Rep 5 16506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Tang W, Teves ME, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Li H, Archer KJ, Peterson DL, Williams DC Jr., Strauss JF 3rd, et al. 2015b. A MEIG1/PACRG complex in the manchette is essential for building the sperm flagella. Development 142 921–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Xu L, Li J, Li B, Bai X, Strauss JF 3rd, Zhang Z & Wang H 2014. Otitis media in sperm-associated antigen 6 (Spag6)-deficient mice. PLoS One 9 e112879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, Chen WN, Chen CJ, Lin YW, Zimmer A & Chen CC 2012. An antinociceptive role for substance P in acid-induced chronic muscle pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 E76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Li W, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Shang X, Zhang L, Zhang S, Li Y, Somoza AV, Delpi B, et al. 2017. IFT25, an intraflagellar transporter protein dispensable for ciliogenensis in somatic cells, is essential for sperm flagella formation. Biol Reprod. 96 993–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May RC, Hall ME, Higgs HN, Pollard TD, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Machesky LM & Sechi AS 1999. The Arp2/3 complex is essential for the actin-based motility of Listeria monocytogenes. Curr Biol 9 759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno RD, Palomino J & Schatten G 2006. Assembly of spermatid acrosome depends on microtubule organization during mammalian spermiogenesis. Dev Biol 293 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno RD & Schatten G 2000. Microtubule configurations and post-translational alpha-tubulin modifications during mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 46 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer D, Curtis EF & Camenzind AR 1990. Combined use of fluorescent peanut agglutinin lectin and Hoechst 33258 to monitor the acrosomal status and vitality of human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 5 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulaw MA, Krause A, Deshpande AJ, Krause LF, Rouhi A, La Starza R, Borkhardt A, Buske C, Mecucci C, Ludwig WD, et al. 2012. CALM/AF10-positive leukemias show upregulation of genes involved in chromatin assembly and DNA repair processes and of genes adjacent to the breakpoint at 10p12. Leukemia 26 1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson LI, Schneider PA, Van Deerlin PG, Kiriakidou M, Driscoll DA, Pellegrini MC, Millinder S, Yamamoto KK, French CK & Strauss JF 3rd, 1999. cDNA cloning and characterization of a human sperm antigen (SPAG6) with homology to the product of the Chlamydomonas PF16 locus. Genomics 60 272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel-King RS, Benashski SE, Harrison A & King SM 1997. A Chlamydomonas homologue of the putative murine t complex distorter Tctex-2 is an outer arm dynein light chain. J Cell Biol 137 1081–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero IB, Herrala AM, Araujo CL, Pulkka AE, Hautaniemi S, Ovaska K, Pryazhnikov E, Kulesskiy E, Ruuth MK, Soini Y, et al. 2013. Transmembrane prostatic acid phosphatase (TMPAP) interacts with snapin and deficient mice develop prostate adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 8 e73072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S, Grzmil P, Drenckhahn JD, Meinhardt A, Adham I, Engel W & Neesen J 2010. Disruption of the murine dynein light chain gene Tcte3-3 results in asthenozoospermia. Reproduction 139 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Wiedemann U, Stuurman N & Vale RD 2003. Molecular requirements for actin-based lamella formation in Drosophila S2 cells. J Cell Biol 162 1079–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro R, Kostetskii I, Olds-Clarke P, Gerton GL, Radice GL & Strauss IJ 2002. Male infertility, impaired sperm motility, and hydrocephalus in mice deficient in sperm-associated antigen 6. Mol Cell Biol 22 6298–6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro R, Tarantino LM, Velazquez F, Kiriakidou M, Hecht NB, Bucan M & Strauss JF 3rd, 2000. Sperm antigen 6 is the murine homologue of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii central apparatus protein encoded by the PF16 locus. Biol Reprod 62 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer K, Bozko PM, Dubiel W & Naumann M 2007. CSN controls NF-kappaB by deubiquitinylation of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J 26 1532–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley L, Lear M, Davidson S, Ross R & MacKenzie A 2011. Evidence for regulatory diversity and auto-regulation at the TAC1 locus in sensory neurones. J Neuroinflammation 8 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silina K, Zayakin P, Kalnina Z, Ivanova L, Meistere I, Endzelins E, Abols A, Stengrevics A, Leja M, Ducena K, et al. 2011. Sperm-associated antigens as targets for cancer immunotherapy: expression pattern and humoral immune response in cancer patients. J Immunother 34 28–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sironen A, Hansen J, Thomsen B, Andersson M, Vilkki J, Toppari J & Kotaja N 2010. Expression of SPEF2 during mouse spermatogenesis and identification of IFT20 as an interacting protein. Biol Reprod 82 580–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sironen A, Kotaja N, Mulhern H, Wyatt TA, Sisson JH, Pavlik JA, Miiluniemi M, Fleming MD & Lee L 2011. Loss of SPEF2 function in mice results in spermatogenesis defects and primary ciliary dyskinesia. Biol Reprod 85 690–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EF & Lefebvre PA 1996. PF16 encodes a protein with armadillo repeats and localizes to a single microtubule of the central apparatus in Chlamydomonas flagella. J Cell Biol 132 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straschil U, Talman AM, Ferguson DJ, Bunting KA, Xu Z, Bailes E, Sinden RE, Holder AA, Smith EF, Coates JC, et al. 2010. The Armadillo repeat protein PF16 is essential for flagellar structure and function in Plasmodium male gametes. PLoS One 5 e12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkina TM & Borisy GG 1999. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J Cell Biol 145 1009–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaney KF & Li R 2016. Function and regulation of the Arp2/3 complex during cell migration in diverse environments. Curr Opin Cell Biol 42 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teves ME, Sears PR, Li W, Zhang Z, Tang W, van Reesema L, Costanzo RM, Davis CW, Knowles MR, Strauss JF 3rd, et al. 2014. Sperm-associated antigen 6 (SPAG6) deficiency and defects in ciliogenesis and cilia function: polarity, density, and beat. PLoS One 9 e107271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari R, Bailes E, Bunting KA & Coates JC 2010. Armadillo-repeat protein functions: questions for little creatures. Trends Cell Biol 20 470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhle S, Medalia O, Waldron R, Dumdey R, Henklein P, Bech-Otschir D, Huang X, Berse M, Sperling J, Schade R, et al. 2003. Protein kinase CK2 and protein kinase D are associated with the COP9 signalosome. EMBO J 22 1302–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalle C & Iervasi G 2014. New insights for matrix Gla protein, vascular calcification and cardiovascular risk and outcome. Atherosclerosis 235 236–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Song W, Hu T, Zhang N, Miao S, Zong S & Wang L 2011. Fank1 interacts with Jab1 and regulates cell apoptosis via the AP-1 pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci 68 2129–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li X, Zhang Z, Wang H & Li J 2015. Expression of prestin in OHCs is reduced in Spag6 gene knockout mice. Neurosci Lett 592 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S, Stoter M, Giamas G, Piesche M, Henne-Bruns D, Banting G & Knippschild U 2006. Casein kinase 1 delta (CK1delta) interacts with the SNARE associated protein snapin. FEBSLett 580 6477–6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Hu X, Zhang Q, Song L, Zhang M, Zhang Y & Zhao S 2015. Spag6 Negatively Regulates Neuronal Migration During Mouse Brain Development. J Mol Neurosci 57 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Wang L, Luo X, Chen L, Yang Z & Liu L 2015. SPAG6 silencing inhibits the growth of the malignant myeloid cell lines SKM-1 and K562 via activating p53 and caspase activation-dependent apoptosis. Int J Oncol 46 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X & Cai Q 2014. Snapin-mediated BACE1 retrograde transport is essential for its degradation in lysosomes and regulation of APP processing in neurons. Cell Rep 6 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebboudj AF, Imura M & Bostrom K 2002. Matrix GLA protein, a regulatory protein for bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Biol Chem 277 4388–4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Yu D, Seo S, Stone EM & Sheffield VC 2012. Intrinsic protein-protein interaction-mediated and chaperonin-assisted sequential assembly of stable bardet-biedl syndrome protein complex, the BBSome. J Biol Chem 287 20625–20635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Jones BH, Tang W, Moss SB, Wei Z, Ho C, Pollack M, Horowitz E, Bennett J, Baker ME, et al. 2005. Dissecting the axoneme interactome: the mammalian orthologue of Chlamydomonas PF6 interacts with sperm-associated antigen 6, the mammalian orthologue of Chlamydomonas PF16. Mol Cell Proteomics 4 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Kostetskii I, Tang W, Haig-Ladewig L, Sapiro R, Wei Z, Patel AM, Bennett J, Gerton GL, Moss SB, et al. 2006. Deficiency of SPAG16L causes male infertility associated with impaired sperm motility. Biol Reprod 74 751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li W, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Teves ME, Liu H, Strauss JF 3rd, Pazour GJ, Foster JA, Hess RA, et al. 2016. Intraflagellar transport protein IFT20 is essential for male fertility and spermiogenesis in mice. Mol Biol Cell. 27 3705–3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Sapiro R, Kapfhamer D, Bucan M, Bray J, Chennathukuzhi V, McNamara P, Curtis A, Zhang M, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, et al. 2002. A sperm-associated WD repeat protein orthologous to Chlamydomonas PF20 associates with Spag6, the mammalian orthologue of Chlamydomonas PF16. Mol Cell Biol 22 7993–8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Shen X, Gude DR, Wilkinson BM, Justice MJ, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC, Eddy EM & Strauss JF 3rd, 2009. MEIG1 is essential for spermiogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 17055–17060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Tang W, Zhou R, Shen X, Wei Z, Patel AM, Povlishock JT, Bennett J & Strauss JF 3rd, 2007. Accelerated mortality from hydrocephalus and pneumonia in mice with a combined deficiency of SPAG6 and SPAG16L reveals a functional interrelationship between the two central apparatus proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 64 360–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Cai Q, Xie Y & Sheng ZH 2012. Snapin recruits dynein to BDNF-TrkB signaling endosomes for retrograde axonal transport and is essential for dendrite growth of cortical neurons. Cell Rep 2 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Interaction between SPAG6 and TAC1.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/TAC1 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and TAC1 interact in yeast. 1. AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+TAC1/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and TAC1 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with TAC1/pEGFP-N2 (panels a & b) alone or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (panels c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). TAC1/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the TAC1/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S2. Interaction between SPAG6 and Moesin.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/Moesin pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and TAC1 interact in yeast. 1. AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+moesin/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and Moesin in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were cotransfected with Moesin/pEGFP-N2 alone (a), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (b-d). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Moesin/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the Moesin/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S3. Interaction between SPAG6 and BBS4.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/BBS4 pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and BBS4 interact in yeast. 1: AH109 only; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 3: SPAG6/pGBKT7+BBS4/pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Co-localization of SPAG6 and BBS4 in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with BBS4/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). BBS4/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the BBS4/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were co-localized.

Figure S4. Interaction between SPAG6 and DAZL in yeast.

(A) Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/DAZL pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and DAZL interact in yeast. 1: SPAG6/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 2: SPAG6/pGBKT7+DAZL/pGADT7; 3: p53/pGBKT7+pGADT7; 4. p53/pGBKT7+IgT/pGADT7. (B) Colocalization of SPAG6 and DAZL in the transfected CHO cells. CHO cells were co-transfected with DAZL/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). DAZL/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the DAZL/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized.

Figure S5. Interaction between SPAG6 and MGP in yeast.

Direct yeast two-hybrid assay. Indicated plasmids were transformed into AH109. The transformed yeast grew on the plates with non-selection medium and selection medium. The yeast transformed with SPAG6/MGP pair and p53/IgT pair grew on both plates, indicating that SPAG6 and MGP interact in yeast. 1: SPAG6/pGBK-T7+pGAD-T7; 2: SPAG6/pGBK-T7+MGP/pGAD-T7; 3: p53/pGBK-T7+pGAD-T7; 4: p53/pGBK-T7+IgT/pGAD-T7. 5: pGAD-T7; 6: MGP/pGAD-T7; 7: pGAD-T7-lgT.

Figure S6. Interaction between SPAG6 and ACTR2 (or ARPC3) in transfected CHO cells.

(A) CHO cells were co-transfected with ACTR2/pEGFP-N2 alone (a, b), or in combination with SPAG6/pTarget (c-f). The CHO cells were immunostained with an anti-SPAG6 antibody. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). ACTR2/GFP only was present in the whole cytoplasm. When SPAG6 was co-expressed, the ACTR2/GFP was recruited to the localization where SPAG6 was present, and the two proteins were colocalized. (B) Similar co-localization assays were performed to examine the interaction between SPAG6 and ARPC3.

Figure S7. Examination of SPINK2 localization in Spink2 knockout mice.

SPINK2 was co-localized with the acrosome marker, peanut lectin in the wild-type mouse (white arrows in the upper panel), but the signal was missing in the Spink2 knockout mouse (lower panel).

Figure S8. Examination of SPINK2 and acrosome in the testis seminiferous tubules of wild type and Spag6-deficient mice using high concentrations of antibody and peanut lectin. Weak SPINK2 (white arrows) and peanut lectin (white arrow heads) signals were present in the Spag6 knockout mice when a high concentration of antibodies (1:100 for SPINK2) and peanut lectin (10 μg/ml of lectin) were used.

Figure S9. Examination of SPAG16L expression in the testis section of the Spag6 knockout mice

Notice that strong SPAG16L signal was detected in spermatocytes and round spermatids of wild-type mice; however, the signal was dramatically reduced in the Spag6 knockout mice.