Abstract

Objective

The University of British Columbia's General Surgery Program delineates a unique and systematic approach to wellness for surgical residents during a pandemic.

Summary Background Data

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health care workers are suffering from increased rates of mental health disturbances. Residents’ duty obligations put them at increased physical and mental health risk. It is only by prioritizing their well-being that we can better serve the patients and prepare for a surge. Therefore, it is imperative that measures are put in place to protect them.

Methods

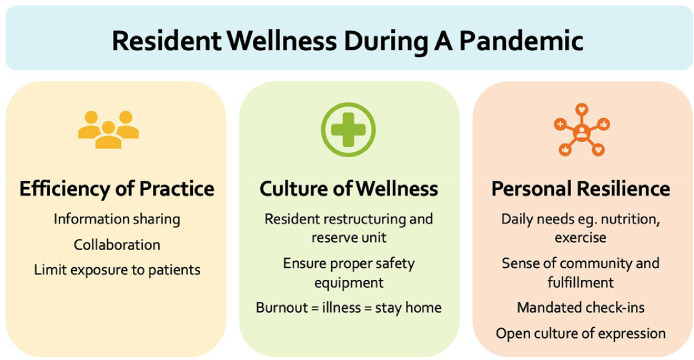

Resident wellness was optimized by targeting 3 domains: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness and personal resilience.

Results

Efficiency in delivering information and patient care minimizes additional stress to residents that is caused by the pandemic. By having a reserve team, prioritizing the safety of residents and taking burnout seriously, the culture of wellness and sense of community in our program are emphasized. All of the residents’ personal resilience was further optimized by the regular and mandatory measures put in place by the program.

Conclusions

The new challenges brought on by a pandemic puts increased pressure on residents. Measures must be put in place to protect resident from the increased physical and mental health stress in order to best serve patients during this difficult time.

Key Words: Wellness, Resident wellness, Surgical education, Resident education, Pandemic, Well-being

INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, a coronavirus (COVID-19) struck the city of Wuhan and was declared a global pandemic within 3 months. By early April, the number of confirmed cases surpassed 20,000, and by mid-April confirmed deaths were over 1000.1 On April 1, 2 weeks into the pandemic, British Columbia had 1066 cases and 25 deaths confirmed.2 The pandemic and its repercussions put an increased strain on our already saturated health care system and inevitably, increased pressure on health care workers. Across Canada, hospitals prepared themselves for a surge in patients; this included the reorganization of residency programs.

Physicians and residents have a high rate of burnout and emotional exhaustion at baseline with 38% of residents reporting burnout.3 In 2019, the Canadian Association of General Surgeons Residents Committee conducted a survey revealing that 75% of general surgery residents reported high levels of burnout with feelings of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion.4 Residents’ were put at increased physical and mental health risk during the pandemic. During the pandemic healthcare workers suffered from increased rates of anxiety, depression and insomnia.5 , 6 It is by prioritizing the well-being of frontline workers that we can better serve patients.

The ideal approach towards optimizing wellness in a pandemic is unknown. Hospitals in Wuhan and New York put measures in place addressing daily needs, communication of current information and psychosocial supports.7 , 8 Bohman et al. believe that physician well-being can be divided into 3 domains that reciprocally influence each other: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness and personal resilience.9 At the University of British Columbia (UBC) General Surgery Program, we have used this model to determine measures that would best support our residents during this difficult time (Fig. 1 ). Our program directors and 2 chief residents worked together to create a new program structure reformatting resident schedules, didactic teaching and wellness initiatives. Although no formal survey was performed, weekly townhalls gave residents an opportunity to present new ideas and to adjust already implemented changes based on their needs, feedback and experience at the hospitals. This article delineates our systematic and holistic approach to wellness for surgical residents during a pandemic.

Figure 1.

Resident wellness during a pandemic.

EFFICIENCY OF PRACTICE

Efficiency of practice refers to the optimization of resources and time.9 During a pandemic, this becomes more relevant than ever as manpower can be scarce and contact must be limited.

With new information being delivered rapidly, it can be overwhelming and time consuming to stay current. The Division of General Surgery organized virtual daily meetings with all teaching hospitals consisting of updates on confirmed cases, deaths, ICU admissions, new guidelines and individual hospitals’ experiences. A brief 5-minute presentation was given by residents every day on a new COVID-19-related paper. In addition, residents had their own group townhall meetings with the program directors weekly or more, if needed, for resident-specific protocol updates. Guidelines on perioperative care of COVID-19 patients and when to personally get tested for COVID-19 were disseminated. As many residents were redeployed to the ICU, a refresher course on ICU management was given by an ICU staff. Routine and scheduled ways of sharing knowledge have taken pressure off the individual surgeon and resident to stay up to date during busy times and allowed sharing of practices province-wide.

Didactic teaching at UBC was previously divided into separate academic half-days for junior and senior residents. Teaching sessions were reformatted to minimize staff and resident's time away from clinical duties by combining the junior and senior teaching sessions. Mandatory twice-a-week shorter virtual sessions were given by chief residents and faculty members. The SCORE curriculum, which is an online platform with specific objectives and assignments on general surgery topics, was maintained throughout. For most of our residents, continuing to provide educational tools and teaching sessions provided them with a sense of normalcy.

To keep our residents safe and maintain social distancing during COVID-19, the workflow of our services was modified. COVID-19 suspected or positive patients were only to be examined by 1 person, either the attending or senior resident. For all patients, only 1 person was to conduct clinical examinations, to minimize patient interactions. By improving our efficiency, we were able to optimize the wellness of our residents and ensure good patient care.

CULTURE OF WELLNESS

A culture of wellness encourages normalizing attitudes and behaviors that promote self-care to foster a sense of community.9 Wellness has been a core value in our General Surgery residency program, predating the era of COVID-19. The pandemic required our program to rapidly restructure in order to prioritize the safety of all residents, thus maintaining their overall wellness.

The UBC General Surgery Program rotations are distributed over 20 different hospital sites across the province, with 1 to 4 residents per service. The 2 largest centres are based in Vancouver and cover quaternary services such as acute care, trauma, hepatobiliary, surgical oncology, minimally invasive, colorectal, endocrine, and pediatric surgery. Other urban and rural centres have broader general surgery services. Early on when the pandemic was first declared, residents were brought back to Vancouver from distant sites to increase the workforce at larger hospitals where the COVID-19 pandemic was more prevalent. This also allowed many of the residents to be reunited with their families. The prospect of residents being away from home and being unwell or having a family member fall unwell was a significant stress for all involved. The rotation structure was modified to now include only 5 quaternary services: acute care, trauma and hepatobiliary surgery at Vancouver General Hospital, general and colorectal surgery at St. Paul's Hospital, and pediatric surgery at BC Children's Hospital. This allowed minimization of resident-to-resident contact, spread of the virus and to create a Resident Reserve Unit (RRU). Residents were equally divided into 3 groups that would rotate weekly: 1/3 for general surgery rotations, 1/3 for the RRU and 1/3 for the ICUs.

In the early phases of the pandemic, there was uncertainty about the board exams for graduating residents. The chief residents were placed in reserve and quarantine until there was certainty about the exam, to ensure illness would not be a reason they could not write. While on the reserve unit, they prepared weekly teaching sessions for the remaining residents, and served important organizational roles.

Another crucial element in prioritizing wellness is to talk about the signs of burnout and how to face this in the midst of a pandemic. Education regarding signs and symptoms of burnout was provided to all residents. Residents with any symptoms of illness, including that of burnout, were mandated to stay home and have a resident from the RRU fill in for them. This system enabled residents to feel supported if they were unwell. In addition, to maximize the safety of our residents, we scheduled mandatory N95 fit testing, donning and doffing teaching and ensured every resident had goggles for protection. By helping with the organization of all the necessary equipment to care for COVID-19 patients, the onus and stress was removed from the individual resident.

PERSONAL RESILIENCE

Personal resilience refers to an individual's ability to maintain overall mental and physical health and thus, prevent burnout.9 Personal resilience is often seen as a responsibility placed on the individual, however, there are many organizational changes that can be implemented to facilitate this.

In 2018, a formal Social and Wellness committee was created to foster interdepartmental relationships and well-being. This committee, which is led by residents and includes faculty members and program directors, meets every 3 months to plan activities and implement wellness initiatives in the residency program. Part of our regular wellness committee's initiatives already included funding an exercise program membership, maintaining a resident lounge and providing regular snacks. With the pandemic, our residents continued attending virtual workouts as a group with their monthly membership. For the residents in hospital, daily meals were provided and paid for by the program. This has helped many of them support each other in staying well and in reducing any stress related to planning meals or exercise time.

Program directors organized weekly virtual meetings with all the residents and with each of the post-graduate years individually. This encouraged productive discussions around surgical care during the pandemic, and also around physical, emotional and social challenges. Regularly scheduled mandatory meetings gave residents a venue to express their feelings and especially useful for those who would otherwise not seek help. Furthermore, to help residents express themselves, they were asked to write an anonymous 55-word paragraph on their COVID-19-related reflections. Short format journaling has been shown to help trainees gain insight and stimulate personal reflection for professional growth.10

Many residents on the reserve unit felt helpless towards the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, when our Department of Surgery was working on a COVID-19 response plan, a third of our residents volunteered to be redeployed to ICUs. Being able to help with essential services at the frontline had a positive effect on many of our residents, as it gave them a sense of purpose. Residents also worked together to find different ways to fundraise for the Vancouver Food Bank while maintaining social distancing and raised over $12,000. This allowed residents to channel their altruism and to gain a sense of fulfillment.

By implementing these measures, residents were supported to improve and maintain their wellness during the pandemic.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic placed an increased burden on the physical and mental health of physicians, therefore, it is imperative that measures are put in place to protect them. The General Surgery Program at UBC optimized the wellness of residents by targeting 3 domains: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness and personal resilience. Efficiency in delivering information and patient care minimizes additional stress to residents that is caused by the pandemic. By having a reserve team, prioritizing the safety of residents and taking burnout seriously, we have continued to emphasize the culture of wellness and sense of community in our program. All of the residents’ personal resilience was further optimized by the regular and mandatory measures put in place by the program. It is only by prioritizing the health of physicians that we can then provide the best possible care for patients. As the saying goes, we must put on our own masks before assisting others.

References

- 1.Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update. 2020. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 2.BC Centre for Disease Control. British Columbia COVID-19 Daily Situation report, April 1, 2020., 2020. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/Health-Info-Site/Documents/BC_Surveillance_Summary_April_1%20Final.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020

- 3.Canadian Medical Association. CMA National Physician Health Survey: a National Snapshot. 2018. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2018-11/nph-survey-e.pdf. Accessed Apr 20, 2020.

- 4.Canadian Associated of General Surgery . Conference presentation Sept 6. 2020. CAGS Resident's Committee Symposium: Resident Fatigue and Fatigue-Related Events Amongst Canadian General Surgery Residents. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. e203976-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu W., Wang H., Lin Y. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ripp J., Peccoralo L., Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City Health System during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang L., Li Y., Hu S. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohman B., Dyrbye L., Sinsky C.A. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0429. Accessed April 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childress M.D. From Doctors' Stories to Doctors' Stories, and Back Again. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19:272–280. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.3.nlit1-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]