Abstract

Discriminating Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from its prodromal form, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), is a significant clinical problem that may facilitate early diagnosis and intervention, in which a more challenging issue is to classify MCI subtypes, i.e., those who eventually convert to AD (cMCI) versus those who do not (MCI). To solve this difficult 4-way classification problem (AD, MCI, cMCI and healthy controls), a competition was hosted by Kaggle to invite the scientific community to apply their machine learning approaches on pre-processed sets of T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) data and the demographic information from the international Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) database. This paper summarizes our competition results. We first proposed a hierarchical process by turning the 4-way classification into five binary classification problems. A new feature selection technology based on relative importance was also proposed, aiming to identify a more informative and concise subset from 426 sMRI morphometric and 3 demographic features, to ensure each binary classifier to achieve its highest accuracy. As a result, about 2% of the original features were selected to build a new feature space, which can achieve the final four-way classification with a 54.38% accuracy on testing data through hierarchical grouping, higher than several alternative methods in comparison. More importantly, the selected discriminative features such as hippocampal volume, parahippocampal surface area, and medial orbitofrontal thickness, etc. as well as the MMSE score, are reasonable and consistent with those reported in AD/MCI deficits. In summary, the proposed method provides a new framework for multi-way classification using hierarchical grouping and precise feature selection.

Keywords: Multi-class classification, Feature selection, Alzheimer’s disease(AD), Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Structural MRI, Hierarchical classification, Relative importance

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most common forms of dementia characterized by progressive cognitive and memory deficits. In 2010, the number of people over 60 years of age living with dementia was estimated at 35.6 million worldwide. This number is expected to almost double every twenty years (Prince et al., 2013). Accordingly, the direct cost of care for AD patients provided by family members and health-care systems is more than $100 billion per year (Alzheimer’s Association, 2013). As an increasingly prevalent disease, AD is regarded as a major worldwide challenge to global health care systems (Brookmeyer et al., 2007). Much effort has been made to find early diagnostic markers to evaluate AD risk pre-symptomatically in a rapid and rigorous way, allowing early interventions that may prevent or at least delay the onset of AD, as well as its prodrome, i.e., mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Reiman et al., 2010).

MCI is a transitional phase characterized by memory disturbance in the absence of dementia, followed by widespread cognitive deficits in multiple domains until a disability threshold is reached (Frisoni et al., 2010). In particular, studies have shown that MCI patients convert to AD at an annual rate of 10–15% per year (Braak and Braak, 1991). It is known that MCI patients who do not convert to AD either remain stable or will develop other forms of dementia, or very rarely, revert to normal status. Meanwhile, to date, there is still no cure for AD-related disease, although treatments include medications and management strategies that may improve the quality of life.

Recently, neuroimage analysis with structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) features for dementia, mainly for AD and MCI, have shown promising results (Sabuncu and Konukoglu, 2015; Liu et al., 2016). Reports indicate anatomical feature representations (e.g., cortical thickness, surface area, grey matter volume, etc.) generated from sMRI can be used to quantify AD-associated brain abnormalities (Cuingnet et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016) and facilitate early diagnosis of MCI/AD. However, sMRI patterns that could reveal pathology about AD-related disease are difficult to find out by human experts. By contrast, pattern recognition algorithms have achieved astonishing performance in many areas (Lecun et al., 2015; Silver et al., 2016). With these algorithms, some patterns hidden in features that may help better discriminate subjects that show similar cognitive performance or symptoms, e.g., MCI vs. cMCI.

In a recent Kaggle competition (https://www.kaggle.com/c/mci-prediction), sMRI features were obtained from the international Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) databases matched for sequence characteristics and were analyzed using FreeSurfer v.5.3. The features space consists of cortical thickness, subcortical volumes, and hippocampal subfields, as previous studies showed the reliability of these morphological measurements for promoting automated diagnosis of AD (Desikan et al., 2009; De et al., 2016; Vasta et al., 2016). Other demographic and behavioral measures include age, gender and Mini-Mental State Examination score (MMSE). Four categories of subjects include 1) stable AD patients, 2) MCI subjects who did not convert their diagnosis in the follow-up, 3) cMCI, individuals who converted to AD, and 4) Healthy Controls (HC). Training dataset consists of 240 subjects with 60 from each group obtained from ADNI dataset, while test data set consists of 160 real subjects from ADNI, with 40 from each group, plus 340 simulated subjects which were calculated by inverse function on each feature’s probability density function uniformly and randomly.

In this paper, we propose a hierarchical grouping process by turning the 4-way classification into five binary classification problems and employ a new feature selection technology based on relative importance. The proposed method is also compared with three popular feature selection methods and four other alternative classifiers to verify its effectiveness. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the methods and structure used for both binary and multi-class classification. In Section 3, we demonstrate the performance of each classifier we employed, the feature space after feature selection algorithm and several results submitted to Kaggle. In Section 4, we present our conclusions and discuss possible future research directions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Structure MRI data, demographic and clinical features

Data used in the Kaggle competition were obtained from the ADNI data (Jack et al., 2008). ADNI is an international project that collects and validates neurological data such as MRI and PET images, genetics or cognitive tests. Subjects from ADNI consist of four categories, those who are stable AD, cMCI, MCI, and HC. Each category of the four classes has a balanced number of subjects (i.e., 100). In the competition, 240 were used for the training set, and 160 for the test set. Meanwhile, the test set was inflated with 340 simulated subjects, therefore, the final sample number for training and testing is 240 and 500 respectively. Demographic and clinical information such as age, gender, and MMSE were also provided for each subject, see more details in Tables 1-3.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Training Participants.

| Group | AD | HC | MCI | cMCI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | – |

| Age | 74.75 ± 7.31 | 72.34 ± 5.67 | 72.19 ± 7.42 | 72.96 ± 7.20 | 0.5906 |

| Gender | 31:29 | 30:30 | 32:28 | 25:35 | 0.1688 |

| MMSE | 23.43 ± 2.11 | 29.15 ± 1.11 | 28.32 ± 1.55 | 27.18 ± 1.87 | 1.05E-49 |

Values reported as Mean ± Standard Deviation(SD); Gender, samples ratio on female: male.

Table 3.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Test Simulated Participants.

| Group | AD | HC | MCI | cMCI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 90 | 77 | 89 | 84 | – |

| Age | 73.18 ± 7.40 | 72.71 ± 7.69 | 70.90 ± 8.54 | 72.94 ± 7.37 | 0.1977 |

| Gender | 51:39 | 34:43 | 53:36 | 44:40 | 0.2213 |

| MMSE | 26.82 ± 3.07 | 26.87 ± 3.08 | 26.85 ± 2.84 | 27.20 ± 2.86 | 0.8272 |

Values reported as Mean ± Standard Deviation(SD); Gender, samples ratio on female: male. Bold values illustrate the difference between real participants and simulated participants.

MRI data were processed by FreeSurfer (v5.3), resulting in various structural morphometric features, including subcortical volumes, hippocampal subfields volumes, cortical volume, cortical surface area, cortical curvature, cortical thickness, and cortical thickness standard deviation. Together, a feature space is established with a dimension of 430, including four demographic metrics (age, gender, diagnosis, and MMSE). The test set contains the same size of imaging features as training set, but without diagnosis labels.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test indicates that there is no statistically significant difference existed in age among classes in both sets, and a Chi-squared test shows no difference in gender. However, an ANOVA test on MMSE showed that there are significant group differences, and two sample t-tests revealed that they exist between HC and AD, HC and MCI, HC and cMCI, AD and MCI, AD and cMCI respectively. No significant differences of MMSE exist between MCI and cMCI.

2.2. Flowchart of the 4-way classification

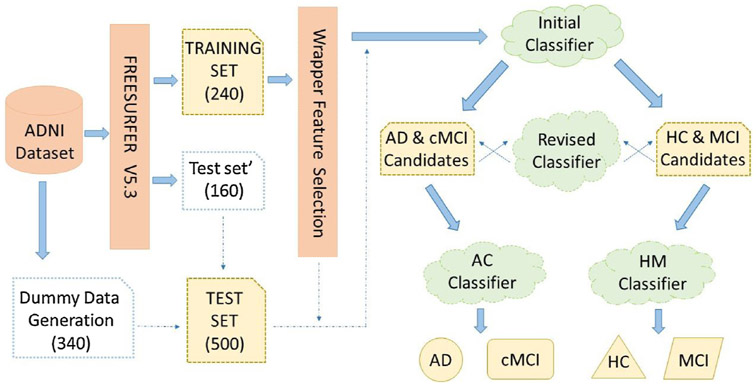

Fig. 1 presents a schematic diagram of the proposed framework using sMRI, demographic, and clinical features. A new feature selection method based on relative importance of variables was employed to establish each classifier’s feature space. The corresponding technical details of this algorithm will be described in Section 2.4. Then with the hierarchical process, classification of four group categories was solved by five binary classification issues. Firstly, we treated HC and MCI as the same group while the other group consisted of cMCI and AD. Then two classes were trained on the initial classifier. After that, two revised classifiers amend results from the initial classifier to decrease the harmful effect that caused by wrong predicted results. To arrive at a final classification decision, we aggregated results from two classifiers which separated HC versus MCI and AD versus cMCI respectively.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of feature selection and hierarchical process with multi-class classification.

2.3. Hierarchical process with multi-class classification

After using feature selection algorithm on all features, we obtain a feature space based on relative samples with better separability on binary classification compared to direct multi-class classification. The hierarchical process is then employed to convert the 4-way multi-class classification problem into several binary classification problems. With all combination patterns, the best solution is that we first treat AD and cMCI as the same category, i.e., AC group (AD & cMCI), while HC together with MCI is treated as the different class, namely, HM group (HC &MCI). They are supposed to be more similar to each other under this circumstance. As shown in Fig. 1, after the initial binary classification between AC and HM, the output result needs to be revised to decrease the harmful effects of misclassification in the initial classifier. AD & cMCI candidates contain those subjects that classified as AD or cMCI patients; meanwhile, Subjects who were considered as HC and MCI composed HC &MCI candidates. Then a revised classifier constitutes with two classifiers (i.e., AHM classifier and cHM classifier) was employed to make sure that AD & cMCI candidates and HC & MCI candidates hold as many correct samples as possible. Specifically, AHM classifier treated AD one class while HC&MCI belong to the different class; cHM classifier treated cMCI as one class while HC&MCI belong to the other category. Each subject should be identified with AHM classifier and cHM classifier respectively; if the discriminant results are both HM class, the subject will be considered as HC & MCI candidates. Else, the subject will be classified as AD & cMCI candidates. After the revised classifier reallocated two candidate groups’ subjects, the final results were generated by the AC and HM classifiers. AC classifier was employed to identify whether a subject belongs to AD or cMCI, while HM classifier is used to discriminate whether a subject should be considered as HC or MCI, as shown in Fig. 1.

2.4. Building feature subspace using relative importance

Based on the original features of our dataset provided, ensemble methods are employed to establish a better feature space. A benefit of using such methods as gradient boosting or random forest is that, after constructed those decision trees, it is relatively straightforward to retrieve importance scores for each feature. In general, importance with a score (Breiman et al., 1984) is calculated using formula (1) that indicates how informative or valuable each feature was averaged across all of the decision trees in the construction of classifier.

| (1) |

tm represents all J-1 internal nodes of m tree in all M trees. The function I returns one if condition true otherwise returns zero.

The high interpretability of feature space leads us to build refined subspace with our proposed new feature selection algorithm which relies on relative importance pools. After this algorithm, we had successfully differentiated several issues on AD-related classification by reducing redundant and noisy features as many as possible. Specifically, features pool was generated by many different kinds of ensemble methods to identify more informative features in original feature space. Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost (Chen and Guestrin, 2016)) generates the first features pool with sorted features importance based on training data. Models including random forest (Breiman, 2001), randomized decision trees (a.k.a. extra-trees) (Geurts et al., 2006), and AdaBoost (Freund and Schapire, 1995) generate the other features pool. This pool assembles three different features in top 10% from different models’ importance features. For clarity purpose, we thus introduce the following definition along with the notations.

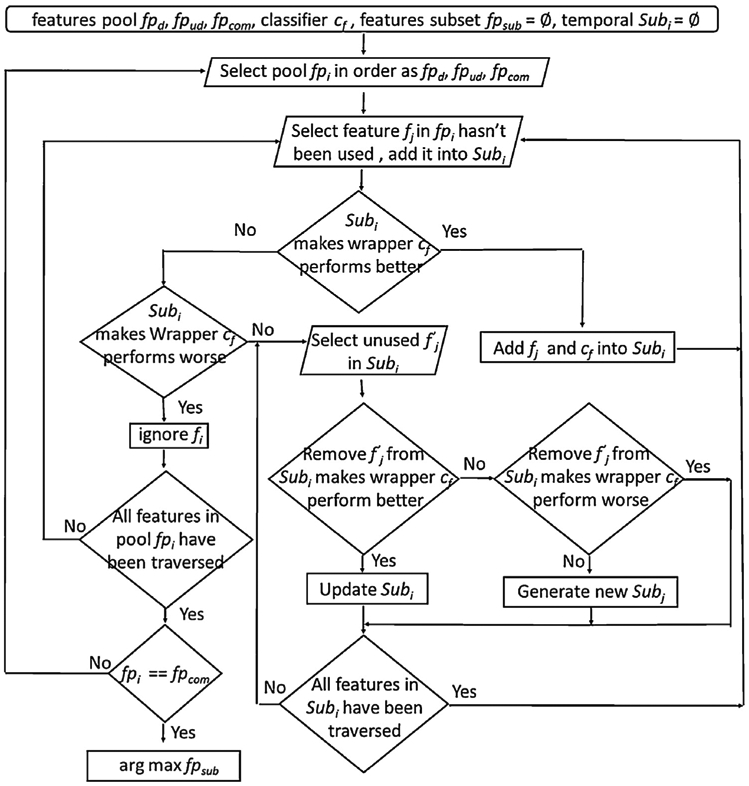

Definition: Features pool in sorted order fpd = {fi … fj} generated from XGBoost, and the other unsorted ones are defined as fpud = {fk … fm}. Complementary set gathers those features which do not appear in pools. Some classifiers ci needs to be used as learners in wrapper model. Furthermore, fpsub saves temporal features subset Subi which includes a specific classifier cf during feature selection period, and the final feature space comes from them. Fig. 2 displays the flowchart of feature selection algorithm.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of our proposed feature selection algorithm.

3. Results

In this Section, we will demonstrate the performance of the proposed method on the 160 real test subjects. Each feature space for binary classifier will be discussed. Meanwhile, some details which may affect final accuracy will also be mentioned.

3.1. Preprocessing on training and test set

Each subject has 426 imaging features and 3 demographic features. Exploratory data analysis (EDA) (Tuckey, 1997) was applied to analyze data sets straightforward. When we consider data with a single feature, we note that outliers exist widely such that almost all subjects have abnormal values in one or two features. Because of this circumstance, it does not make sense to remove these outliers. Instead, we zoom their values into the regular scale that contains most of the values. For example, the mean value of left head caudal anterior cingulate thickness feature between four categories in training set is almost 2500. However, the same feature in thirteen subjects has a value between 2 and 4. To deal these outliers, we assume that these features follow on multimodal distribution.

As mentioned above, the test set consisted of both simulated data and real subjects. Table 3 shows some statistical scores for simulated data. These scores on MMSE indicates that it may lose some useful discriminative features when they have simulated artificially, like P-value criteria of MMSE on simulated data do not exist significant difference. Furthermore, outliers appear more frequently in simulated data, in which almost all subjects have abnormal values in one or two features. Since the final official score was only calculated on real test data, in this paper, we focus on the results for 160 real subjects in the test set.

3.2. Binary classification with feature selection algorithm

Feature selection based on relative importance can help construct an improved feature space. To compare its performance with other popular methods, we introduced three public biomedical data sets, including the LSVT Voice Rehabilitation (Tsanas et al., 2014), Colon Cancer (Alon et al., 1999) and the Leukemia Cancer (Golub et al., 1999), which also have hundreds of features in dimension. Our algorithm is compared with traditional methods like principal component analysis (PCA), SVM-FoBa (Jie et al., 2015), SVM-RFE (Guyon, 2001). We performed a leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) procedure, which is known to be an almost unbiased estimator of the generalization performance of a classifier (Kohavi, 1995). The results with different feature selection algorithms are listed in Table 4, suggesting that the proposed method achieves higher or equivalent performance as the other methods within a small number of features.

Table 4.

Four classifiers’ performance after different feature selection algorithm.

| LSVT Voice | Colon Cancer | Leukemia Cancer |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | No. features | 11–12 | 7 | 6 |

| Methods | Accuracy | 91.27% | 98.39% | 98.61% |

| Sensitivity | 83.33% | 97.50% | 96.00% | |

| Specificity | 95.24% | 100% | 100% | |

| SVM-FoBa | No. features | 47 | 29–30 | 30–38 |

| Accuracy | 90.48% | 87.10% | 98.61% | |

| Sensitivity | 85.71% | 92.50% | 96.00% | |

| Specificity | 92.86% | 86.36% | 100% | |

| Forward Selection | No. features | 83 | 37–39 | 39–43 |

| Accuracy | 87.30% | 85.48% | 97.22% | |

| Sensitivity | 85.71% | 90.00% | 96.00% | |

| Specificity | 90.48% | 86.36% | 100% | |

| SVM-RFE | No. features | 67–68 | 31 | 82–84 |

| Accuracy | 84.92% | 87.10% | 98.61% | |

| Sensitivity | 85.71% | 90.00% | 96.00% | |

| Specificity | 86.90% | 86.36% | 100% |

No. features denote the number of features that model used for binary classification.

After feature selection period, each classifier generates a much more refined feature space. Only about 2% original features saved while performs on the training set even better in ten-fold crossvalidation. Table 5 shows feature space which each classifier used for discrimination.

Table 5.

Selected features for each classifier.

| classifiers | feature space based on feature selection |

|---|---|

| Initial | MMSE_b1, Left-VentralDC, lh_rostralanteriordngulate_thickness_std, lh_medialorbitofrontal_thickness, rh_entorhinal_volume, Left-Accumbens-area, lh_superiorfronta_meancurv, lh_parstriangularis_thicknessstd, right_subiculum, GENDER, lh_temporalpole_thicknessstd, lh_temporalpole_volume, Left-Hippocampus, rh_cuneus_area |

| AC | MMSE_bl, lh_parahippocampa_area, lh_rostralanteriorcingulate_volume, lh_transversetemporal_thickness, rh_fusiform_area, lh_middletemporal_thickness, lh_parahippocampa_meancurv, |

| HM | rh_precuneus_area, Right-Cerebellum-Cortex, lh_parahippocampal_volume, rh_medialorbitofrontal_thickness, left_CA1, 5th-Ventricle, lh_transversetemporal_area, MaskVol-to-eTIV, Right-Cerebellum-Cortex, rh_temporalpole_thicknessstd, lh_WhiteSurfArea_area, rh_precuneus_area, GENDER, Right-Hippocampus_hipposubfields, Right-VentralDC |

| AHM | MMSE_bl, rh_isthmuscingulate_volume, Left-Inf-Lat-Vent, lh_caudalanteriorcingulate_thicknessstd, rh_fusiform_thicknessstd, lh_parsopercularis_thicknessstd, lh_transversetemporal_thickness, CC.Mid.Posterior, lh_middletemporal_thickness, Right-Cerebellum-White-Matter rh_temporalpole_thickness, lh_entorhina_thicknessstd, |

| cHM | lh_rostralanteriorcingulate_thicknessstd, lh_precuneus_thicknessstd, GENDER, Left-Inf-Lat-Vent, MMSE_bl, rh_entorhinal_thickness, lh_bankssts_area, left_presubiculum, rh_superiorparietal_thickness, lh_entorhinal_volume, rh_parsorbitalis_area, rh_precentral_volume, lh_frontalpole_volume, lh_isthmuscingulate_volume, lh_xontalpole_thicknessstd, lh_isthmuscingulate.thicknessstd, |

We use the same feature name as provided in the Kaggle data sets.

Five classifiers which are initial classifiers, AD vs. HM classifier, cMCI vs. HM classifier, AC classifier and HM classifier train with features generated from our feature selection algorithm. Many classifiers are employed as wrappers in our algorithm. SVM, Naïve Bayesian, Random Forest, Extra-trees, AdaBoost, and XGBoost are treated as wrapper candidates (Kohavi and John, 1997), which was employed in classification only based on their performance on the feature space. Note that a classifier with the same algorithm (i.e., XGBoost) can have different parameters in different situations. Therefore, a grid-search method was used to tune all parameters to get the best performance for each classifier. Table 6 illustrates the details of five classifiers with some indexes. The index ‘Type’ demonstrates which classifier is used on feature selection period; ‘FS’ calculates the dimension of each feature subspace; ‘DS’ index counts samples of data space for each class on training set, while ‘DST’ counts samples of data space for each class on test set; ‘CV’ presents the mean accuracy with ten-fold cross-validation on training set; ‘Final’ presents the performance of each classifier on test set with only real subjects. Random forest, extra-trees, AdaBoost and XGBoost can output the relevant importance of each feature in classification. Then classifiers which are employed after feature selection period are XGBoost and support vector machine (SVM) with radial basic function as the kernel function. XGBoost is an implementation of gradient boosted trees with great performances on machine learning competitions and SVM with small dataset can still perform well.

Table 6.

Five classifiers performance with feature selection.

| Classifier | Initial | AHM | cHM | AC | HM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | XGBoost | XGBoost | XGBoost | SVM | XGBoost |

| FS | 14 | 12 | 16 | 8 | 15 |

| DS | 120:120 | 60:120 | 60:120 | 60:60 | 60:60 |

| CV | 91.7% | 97.2% | 90.6% | 93.3% | 86.7% |

| DST | 80:80 | 40:80 | 40:80 | 40:40 | 40:40 |

| Final | 76.9% | 88.3% | 77.5% | 87.5% | 56.25% |

Initial, AD&cMCI vs HC&MCI classifier; AHM, AD vs HC&MCI classifier; cHM, cMCI vs HC&MCI classifier; AC, AD vs cMCI classifier; HM, HC vs MCI classifier

3.3. Multi-class classification with hierarchical process

As the proposed feature selection algorithm yields good performance on several binary classification issues with the training set, multi-class classification into should be separated from four group categories into some binary classification problems. These classifiers which we employed on Fig. 1 were combined to generate the final category for each subject.

The performance of our system is evaluated by using metrics of precision, recall, and F1-score. Traditional indicators like accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity are mainly used for binary classification problem, while since we are working on 4-way classification, precision, recall, and f1-score are more straightforward to compare the performance in full perspectives. These measures are defined as follows:

Furthermore, the confusion matrix is a specific table that allows visualization of the performance of an algorithm. With these metrics, we can reveal more details on models’ performance. As listed in Table 7, three different models are illustrated, which are models submitted to Kaggle at different times. The official score is calculated by dividing the sum of the number on the diagonal (i.e., the right number that model predicted for each class) by the whole number (i.e., 160), which represents the mean precision on all four categories.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix for multi-class classification.

| Result | Best-Submission |

Selection-Submission |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ad | hc | mci | cmci | ad | hc | mci | cmci | |

| AD | 35 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| HC | 1 | 15 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 12 | 10 |

| MCI | 7 | 8 | 5 | 20 | 3 | 15 | 11 | 11 |

| cMCI | 8 | 3 | 0 | 29 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 21 |

| Precision | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.47 |

| Recall | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.53 |

| F1-score | 0.77 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.88 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.49 |

| Official Score | 52.500% | 54.387% | ||||||

The lowercase ad, hc, mci, and cmci denotes the number of AD, HC, MCI and cMCI which generated from our algorithm. The capital AD, HC, MCI, and cMCI mean the number of real data (all these numbers exclude the simulated data).

As listed in Table 7, the results from selection-submission show better performance than the best-submission. The model which generated selection-submission result has almost the same structure as the model that generated the best-submission result. The only difference is whether a revised classifier is added to the framework or not. The model with a revised classifier generated the selection-submission result. It showed an improved performance as two candidates have less error-classifying subjects than the model without a revised classifier. Note that the best submission accuracy in this Kaggle competition reach 61.875%, while the 2nd −9th places have scored about 55% depending on their model’s performance with test data of real human subjects.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of feature selection algorithm and hierarchical process

On the training set, each binary classifier shows good discriminative capability, as the CV row listed in Table 6. Unfortunately, the generalization on test data dropped considerably, especially for HM classifier. Features used in our model to classify HC and MCI maybe cannot reveal their difference efficiently. This issue suggests us to find the better algorithm in future work or features on other modalities (Weiner et al., 2015). Overfitting might cause the different performance on training and test set although we used 10-fold CV to avoid this issue (Varma and Simon, 2006). The size of the data can impact model generalization. To obtain good performance on both test and training set, regularization techniques or weights on different features pools would be added into our feature selection algorithm in the future.

4.2. Analysis of selected features

In Table 5, we show all features that were used to build each feature space after our feature selection algorithm. Note that in previous studies, regions including hippocampal information (in Initial, AC and HM feature space), parahippocampal gyrus (in AC and HM feature space), medial orbitofrontal cortex (in Initial and HM feature space), middle temporal gyrus (in AC and AHM feature space), precuneus or cuneus (in Initial, HM and cHM feature space), as well as regions in temporal pole (in all feature space but cHM), have been shown are related to AD (Convit et al., 2000; Hua et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2014) or MCI (Albert et al., 2011) classification. For example, Hippocampal volume has been shown to be effective in identifying subjects more likely to dementia (Weiner et al., 2015) and Yu et al. (2014) characterized hippocampal volume as an enrichment biomarker. Furthermore, it has been reported that MMSE and gender are important factors in AD studies (Miyashita et al., 2007; Hebert et al., 2013). The selected features of our method are congruent with those findings from previous works.

In this paper, we proposed a 4-way classification framework to discriminate MCI subtypes with AD and HC. To solve the challenging problem, we present a novel feature selection algorithm based on relative importance with a hierarchical grouping process. Compared with conventional methods, the proposed framework can easily and effectively shrink the original feature space into a concise and informative subset for classification. Moreover, an elaborate hierarchical process turned multi-class classification into several binary problems. The final result for each subject’s label comes from these binary classifiers. Two results with confusion matrix were provided to directly illustrate the whole 4-way classification performance, with three indexes for measuring the multi-class classification accuracy. The performance on our selected model reached 54.375% for 4-class separation (25%, random chance). More importantly, the selected features based on our feature selection algorithm are highly related to AD/MCI deficits. In summary, there is still a long way to go to explore more efficient algorithms to improve the early differentiation between MCI and cMCI, which may provide potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of AD and more effective intervention.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Test Real Participants.

| Group | AD | HC | MCI | cMCI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | – |

| Age | 73.11 ± 8.05 | 74.88 ± 5.48 | 72.40 ± 8.04 | 71.75 ± 6.23 | 0.2351 |

| Gender | 17:23 | 22:18 | 17:23 | 15:25 | 0.4449 |

| MMSE | 22.68 ± 1.98 | 29.00 ± 1.10 | 27.65 ± 1.86 | 25.58 ± 1.80 | 1.59E-36 |

Values reported as Mean ± Standard Deviation(SD); Gender, samples ratio on female: male. Bold values illustrate the difference between real participants and simulated participants.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We propose a new feature selection algorithm based on relative importance.

Hierarchical progress is helpful to solve 4-way classification on AD-related problem.

This paper summarizes our response to the Kaggle competition.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the National High Tech Development Program (863 Plan, No. 2015AA020513), and China National Natural Science Foundation (No. 81471367, 61773380), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB02060005) and National Institute of Health (1R01EB005846, 1R01MH094524, P20GM103472). The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, 2011. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia 7, 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U, Barkai N, Notterman DA, Gish K, Ybarra S, Mack D, Levine AJ, 1999. Broad patterns of gene expression revealed by clustering analysis of tumor and normal colon tissues probed by oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 96, 6745–6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association, 2013. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2013 (9), 208–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA, 1984. Classification and Regression Trees. CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L, 2001. Random forests. Mach. Learn 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R,Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM, 2007. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia 3,186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Guestrin C, 2016. Xgboost A scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, ACM, pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, De Asis J, De Leon M, Tarshish C, De Santi S, Rusinek H, 2000. Atrophy of the medial occipitotemporal, inferior, and middle temporal gyri in non-demented elderly predict decline to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 21,19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuingnet R, Gerardin E, Tessieras J, Auzias G, Lehricy S, Habert MO, Chupin M, Benali H, Colliot O, 2011. Automatic classification of patients with Alzheimer’s disease from structural MRI: a comparison of ten methods using the ADNI database. Neuroimage 56, 766–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De VF, Schouten TM, Hafkemeijer A, Dopper EG, van Swieten JC, De RM, de Van GJ, Rombouts SA, 2016. Combining multiple anatomical MRI measures improves Alzheimer’s disease classification. Hum. Brain Mapp 37, 1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Hess CP, Dillon WP, Glastonbury CM, Weiner MW, Schmansky NJ, Greve DN, Salat DH, Buckner RL, 2009. Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain A J. Neurol 132, 2048–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund Yoav, Schapire Robert E., 1995. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting In: European Conference on Computational Learning Theory. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB, Fox NC,Jack CR Jr, Scheltens P, Thompson PM, 2010. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol 6, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts P, Ernst D, Wehenkel L, 2006. Extremely randomized trees Mach. Learn. 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA, 1999. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science 286, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon I, 2001. Erratum Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA, 2013. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 1778 (80). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow AD, Lee S, Klunder AD, Toga AW, Lepore N, Chou YY, Brun C, Chiang MC, Barysheva M, 20083D characterization of brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using tensor-based morphometry. Neuroimage 41,19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack Clifford R. Jr., Bernstein Matt A., Fox Nick C., Thompson Paul, Alexander Gene, Harvey Danielle, Borowski Bret, Britson Paula J., Whitwell Jennifer L., Ward Chadwick, Dale Anders M., Felmlee Joel P., Gunter Jeffrey L., Hill Derek L.G., Killiany Ron, Schuff Norbert, Fox-Bosetti Sabrina, Lin Chen, Studholme Colin, DeCarli Charles S., Krueger Gunnar, Ward Heidi A., Metzger Gregory J., Scott Katherine T., Mallozzi Richard, Blezek Daniel, Levy Joshua, Debbins Josef P, Fleisher Adam S., Albert Marilyn, Green Robert, Bartzokis George, Glover Gary, Mugler John, Weiner Michael W., 2008. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. Alzheimers Dementia 27, 685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie NF, Zhu MH, Ma XY, Osuch EA, Wammes M, Theberge J, Li HD, Zhang Y, Jiang TZ, Sui J, 2015. Discriminating bipolar disorder from major depression based on SVM-FoBa: efficient feature selection with multimodal brain imaging data. IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev 7,320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi R, John GH, 1997. Wrappers for feature subset selection. Artif. Intell 97, 273–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi R, 1995. A study ofcross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G, 2015. Deep learning. Nature 521,436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wee CY, Chen H, Shen D, 2014. Inter-modality relationship constrained multi-modality multi-task feature selection for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment identification. Neuroimage 84, 466–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Zhang D, Shen D, 2016. Relationship induced multi-template learning for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 1463–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita A, Arai H, Asada T, Imagawa M, Matsubara E, Shoji M, Higuchi S, Urakami K, Kakita A, Takahashi H, 2007. Genetic association of CTNNA3 with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in females. Hum. Mol. Genet 16, 2854–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP, 2013. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and meta analysis. Alzheimers Dementia J. Alzheimers Assoc 9, 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Langbaum JBS, Tariot PN, 2010. Alzheimer’s prevention initiative: a proposal to evaluate presymptomatic treatments as quickly as possible. Biomarkers Med. 4,3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabuncu MR, Konukoglu E, 2015. Clinical prediction from structural brain MRI scans: a large-scale empirical study[J]. Neuroinformatics 13 (1), 31–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver D, Huang A, Maddison CJ, Guez A, Sifre L, Van dD G, Schrittwieser J, Antonoglou I, Panneershelvam V, Lanctot M, 2016. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsanas A, Little MA, Fox C, Ramig LO, 2014. Objective automatic assessment of rehabilitative speech treatment in parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. A Pub. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 22, 181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey JW, 1977. Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Varma S, Simon R, 2006. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinf. 7, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta R, Augimeri A, Cerasa A, Nigro S, Gramigna V, Nonnis M, Rocca F, Zito G, Quattrone A, 2016. Hippocampal subfield atrophies in converted and not-converted Mild Cognitive Impairments patients by a Markov random fields algorithm. Curr. Alzheimer Res 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Cedarbaum J, Green RC, Harvey D, Jack CR, Jagust W, 2015. 2014 Update of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimer’s Dementia 11, e1–e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Sun J, Wolz R, Stephenson D, Brewer J, Fox NC, Cole CR, Jack CR Jr, Hill DL, Schwarz AJ, 2014. Operationalizing hippocampal volume as an enrichment biomarker for amnestic mild cognitive impairment trials: effect of algorithm, test-retest variability, and cut point on trial cost, duration, and sample size. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Gao Y, Gao Y, Munsell B, Shen D, 2016. Detecting anatomical landmarks for fast Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 2524–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]