Abstract

Background

The association between triglyceride glucose (TyG) index and coronary atherosclerotic change remains unclear. We aimed to evaluate the association between TyG index and coronary plaque progression (PP) using serial coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA).

Methods

A total of 1143 subjects (aged 60.7 ± 9.3 years, 54.6% male) who underwent serial CCTA with available data on TyG index and diabetic status were analyzed from The Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography IMaging (PARADIGM) registry. PP was defined as plaque volume (PV) (mm3) at follow-up minus PV at index > 0. Annual change of PV (mm3/year) was defined as PV change divided by inter-scan period. Rapid PP was defined as the progression of percent atheroma volume (PV divided by vessel volume multiplied by 100) ≥ 1.0%/year.

Results

The median inter-scan period was 3.2 (range 2.6–4.4) years. All participants were stratified into three groups based on TyG index tertiles. The overall incidence of PP was 77.3%. Baseline total PV (group I [lowest]: 30.8 (0.0–117.7), group II: 47.2 (6.2–160.4), and group III [highest]: 57.5 (8.4–154.3); P < 0.001) and the annual change of total PV (group I: 5.7 (0.0–20.2), group II: 7.6 (0.5–23.5), and group III: 9.4 (1.4–27.7); P = 0.010) were different among all groups. The risk of PP (odds ratio [OR] 1.648; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.167–2.327; P = 0.005) and rapid PP (OR 1.777; 95% CI 1.288–2.451; P < 0.001) was increased in group III compared to that in group I. TyG index had a positive and significant association with an increased risk of PP and rapid PP after adjusting for confounding factors.

Conclusion

TyG index is an independent predictive marker for the progression of coronary atherosclerosis.

Clinical registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02803411

Keywords: Triglyceride glucose index, Coronary artery disease, Atherosclerosis, Coronary computed tomography angiography

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. It is important to understand the coronary atherosclerotic progression for the prevention of adverse cardiovascular (CV) events. Numerous previous studies have suggested the significant role of insulin resistance (IR) in the development of CAD [2–4]. Recently, the triglyceride glucose (TyG) index has been suggested to be a reliable surrogate marker of IR [5–7]. Several cross-sectional studies have reported that TyG index is associated with CAD, especially with coronary artery calcification (CAC) [8, 9]. However, longitudinal data on the association between TyG index and coronary plaque progression (PP) is scarce. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is a well-established non-invasive imaging tool with high diagnostic performance for coronary atherosclerosis and predictive value for adverse CV events [10–13]. Therefore, we aimed to examine the association between baseline TyG index and coronary PP using serial CCTA.

Methods

Study design and populations

The Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography IMaging (PARADIGM) is a prospective, international, and multicenter observational registry designed to evaluate associations between clinical variables and coronary atherosclerotic changes using serial CCTA [14]. Between 2003 and 2015, 2252 consecutive subjects underwent serial CCTA at 13 centers in 7 countries. Among these subjects, 1143 subjects with available information on TyG index and diabetic status were included in the present study. The characteristics of coronary plaques in all participants were categorized based on the TyG index tertile. TyG index was calculated as ln [fasting triglycerides (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2]. Diabetes was defined as treatment with oral hypoglycemic agent or insulin or fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 126 mg/dL. The institutional review boards approved this study at each site.

Acquisition and interpretation of CCTA

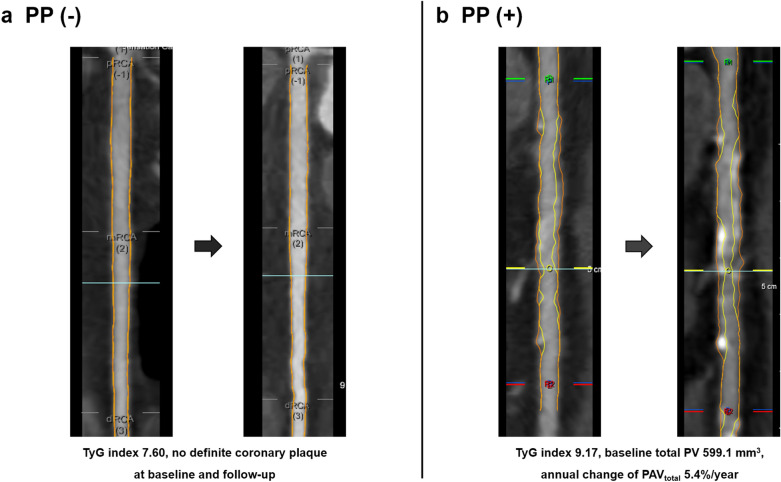

All data acquisition and post-processing of CCTA were in accordance with the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography guidelines [15, 16]. CCTA was performed with a ≥ 64-detector row scanner at all centers. All datasets from each center were transferred to an offline workstation for analysis with a semi-automated plaque analysis software (QAngioCT Research Edition v2.1.9.1; Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands) using manual correction. Segments with diameter ≥ 2 mm were evaluated using a modified 17-segment American Heart Association model [16]. Regardless of the presence of atherosclerotic plaques, plaque volume (PV) (mm3) of every coronary segment was obtained and summated to generate total PV per patient. Coronary plaques were further classified by composition according to the pre-defined intensity cut-offs in Hounsfield units (HU) for calcified plaques (≥ 351 HU), fibrous plaques (131–350 HU), fibro-fatty plaques (31–130 HU), and necrotic cores (-30 to 30 HU) [17, 18]. For comparing longitudinal CCTA images, all baseline and follow-up coronary segments were registered together with fiduciary landmarks, including the distance from the ostia or branch vessel take-offs. PV change was defined as plaque volume at follow-up CCTA minus plaque volume at baseline CCTA. Annual change of PV (mm3/year) was defined as total PV change divided by inter-scan period. Moreover, normalized total atheroma volume (TAVnorm) (mm3) was defined as total PV divided by vessel length, multiplied by the mean participants’ vessel length. Annual change of TAVnorm (mm3/year) was defined as TAVnorm divided by the inter-scan period. While total percent atheroma volume (PAVtotal) (%) was defined as PV divided by vessel volume, multiplied by 100, annual change of PAVtotal (%/year) was defined as total PAV divided by inter-scan period, and plaque progression (PP) was defined as the difference in plaque volume between follow-up and baseline CCTA > 0. Further, rapid PP (%/year) was defined as an annual progression of PAV ≥ 1.0% [19, 20]. Representative CCTA images are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Representative CCTA images. CCTA coronary computed tomography angiography, TyG triglyceride glucose

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD or medians and interquartile range, while categorical variables are presented as absolute values and proportions. Continuous variables were compared using an independent t test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate and categorical variables were compared using the χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Coronary characteristics across TyG index tertiles were compared using one-way analysis of variance or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between clinical variables and coronary PP. Further, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the independent impact of TyG index on coronary PP. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were considered confounding variables and entered into the multivariate logistic regression models, except the individual component of TyG index. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the 1143 participants (624 male, 54.6%) was 60.7 ± 9.3 years. Median inter-scan period was 3.2 (range, 2.6–4.4) years. Coronary PP was observed in 883 (77.3%) participants during follow-up. The clinical characteristics of participants according to PP are presented in Table 1. Age, systolic blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), serum triglyceride and FBG levels, prevalence of male sex, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and the use of aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), and statin were significantly higher in subjects with PP than in those without it. Subjects with PP had significantly lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) than those without PP. TyG index values were higher in subjects with PP than in those without it (8.85 ± 0.60 vs. 8.69 ± 0.55; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (n = 1143) | PP (−) (n = 260) | PP (+) (n = 883) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.7 ± 9.3 | 58.7 ± 9.6 | 61.3 ± 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 624 (54.6) | 122 (46.9) | 502 (56.9) | 0.005 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 126.1 ± 16.6 | 123.7 ± 16.3 | 126.8 ± 16.6 | 0.011 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 77.0 ± 10.6 | 75.9 ± 11.1 | 77.3 ± 10.5 | 0.079 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8 ± 3.0 | 24.3 ± 3.0 | 25.0 ± 3.0 | 0.002 |

| BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2, n (%) | 493 (43.9) | 97 (37.5) | 396 (45.8) | 0.017 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 674 (59.0) | 123 (47.3) | 551 (62.5) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 319 (27.9) | 48 (18.5) | 271 (30.7) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 381 (33.3) | 69 (26.5) | 312 (35.4) | 0.008 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 213 (18.6) | 42 (16.2) | 171 (19.4) | 0.239 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| Aspirin | 555 (48.6) | 107 (41.2) | 448 (50.8) | 0.006 |

| Beta blocker | 353 (31.0) | 81 (31.2) | 272 (30.9) | 0.940 |

| ACEI/ARB | 389 (34.2) | 67 (25.9) | 332 (36.6) | 0.001 |

| Statin | 520 (45.5) | 89 (34.2) | 431 (49.5) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin therapy | 33 (2.9) | 5 (2.0) | 28 (3.2) | 0.294 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 182.6 ± 38.4 | 184.4 ± 39.6 | 182.0 ± 38.1 | 0.393 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 143.3 ± 83.1 | 132.8 ± 73.9 | 146.4 ± 85.4 | 0.020 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 48.7 ± 12.3 | 50.3 ± 12.8 | 48.2 ± 12.1 | 0.016 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 111.5 ± 34.1 | 113.5 ± 34.2 | 110.9 ± 34.0 | 0.289 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.01 ± 0.67 | 0.96 ± 0.47 | 1.01 ± 0.72 | 0.233 |

| FBG, mg/dL | 110.7 ± 35.0 | 104.2 ± 28.6 | 112.7 ± 36.5 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.46 ± 1.27 | 6.26 ± 1.19 | 6.51 ± 1.28 | 0.067 |

| TyG index | 8.81 ± 0.59 | 8.69 ± 0.55 | 8.85 ± 0.60 | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%)

ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TyG triglyceride glucose

Comparison of baseline PV and annual change of PV according to TyG index tertile

Baseline total PV (mm3) was as follows: group I [lowest]: 30.8 (0.0–117.7), group II: 47.2 (6.2–160.4), and group III [highest]: 57.5 (8.4–154.3), P < 0.001. Baseline TAVnorm values were as follows: group I, 33.0 (0.0–122.3); group II, 54.1 (7.4–192.3); and group III, 61.2 (9.5–165.6); P = 0.001. PAVtotal was as follows: group I, 1.6 (0.0–6.1); group II: 2.8 (0.4–8.8); and group III: 3.0 (0.5–8.1); P = 0.001. There were significant differences among the TyG index tertile groups at baseline. Regarding coronary plaque subtypes, there was a significant difference in the fibrous, fibrous-fatty, necrotic-core, and dense calcium PVs among all groups at baseline. During follow-up, the annual change of the total PV was as follows: group I, 5.7 (0.0–20.2); group II, 7.6 (0.5–23.5); and group III, 9.4 (1.4–27.7); P = 0.0101; 2) and of TAVnorm was as follows: group I, 6.2 (0.0–19.9); group II, 7.8 (0.5–25.4); and group III, 9.3 (1.7–31.2); P = 0.005. PAVtotal [group I: 0.3 (0.0–0.9), group II: 0.4 (0.0–1.3), and group III: 0.5 (0.1–1.4); P = 0.006] was different among all the groups. There was a significant difference in the annual change of fibrous and dense calcium PVs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline and changes in the coronary plaque characteristics

| Total (n = 1143) | TyG index tertiles | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (lowest) 7.20–8.53 (n = 382) | II 8.54–9.02 (n = 388) | III (highest) 9.03–10.84 (n = 373) | |||

| At baseline | |||||

| Plaque volume (mm3) | |||||

| Total | 44.1 (3.5–139.6) | 30.8 (0.0–117.7) | 47.2 (6.2 −160.4) | 57.5 (8.4–154.3) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrous | 20.3 (0.8–59.1) | 13.7 (0.0–49.7) | 22.5 (2.9–67.3) | 24.3 (3.8–64.4) | 0.001 |

| Fibrous-fatty | 3.5 (0.0–23.4) | 1.4 (0.0–14.8) | 3.6 (0.0–25.3) | 6.1 (0.0–31.8) | < 0.001 |

| Necrotic-core | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 0.0 (0.0–0.7) | 0.0 (0.0–1.6) | 0.1 (0.0–2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Dense calcium | 6.4 (0.0–38.1) | 2.8 (0.0–33.5) | 8.0 (0.0–41.2) | 8.3 (0.0–36.5) | 0.027 |

| TAVnorm (mm3) | 47.6 (2.6–151.5) | 33.0 (0.0–122.3) | 54.1 (7.4–192.3) | 61.2 (9.5–165.6) | 0.001 |

| PAVtotal (%) | 2.5 (0.1–7.7) | 1.6 (0.0–6.1) | 2.8 (0.4–8.8) | 3.0 (0.5–8.1) | 0.001 |

| Annual change | |||||

| Plaque volume (mm3/year) | |||||

| Total | 7.6 (0.5–22.2) | 5.7 (0.0–20.2) | 7.6 (0.5–23.5) | 9.4 (1.4–27.7) | 0.010 |

| Fibrous | 1.9 (0.0–8.6) | 1.1 (0.0–6.9) | 1.9 (0.0–8.7) | 2.8 (0.0–9.8) | 0.022 |

| Fibrous-fatty | 0.0 (-0.8–1.4) | 0.0 (-0.5–0.9) | 0.0 (-0.9–1.3) | 0.0 (-1.0–2.3) | 0.341 |

| Necrotic-core | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (-0.1–0.1) | 0.659 |

| Dense calcium | 3.4 (0.1–11.7) | 2.1 (0.0–8.7) | 3.7 (0.3–12.1) | 3.9 (0.4–13.3) | 0.016 |

| TAVnorm (mm3/year) | 7.7 (0.4–24.4) | 6.2 (0.0–19.9) | 7.8 (0.5–25.4) | 9.3 (1.7–31.2) | 0.005 |

| PAVtotal (%/year) | 0.4 (0.0–1.2) | 0.3 (0.0–0.9) | 0.4 (0.0–1.3) | 0.5 (0.1–1.4) | 0.006 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range)

PAVtotal total percent atheroma volume, TAVnorm normalized total atheroma volume, TyG triglyceride glucose

Association of clinical variables with coronary atherosclerotic change

Age (odds ratio [OR] 1.031; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.016–1.047; P < 0.001), male sex (OR 1.490; 95% CI 1.129–1.967; P = 0.005), systolic BP (OR 1.012; 95% CI 1.003–1.022; P = 0.012), BMI (OR 1.077; 95% CI 1.026–1.130; P = 0.003), and HDL-C (OR 0.987; 95% CI 0.976–0.998; P = 0.017) were associated with coronary PP. Among the TyG tertile groups, PP risk was increased in group III compared with that in group I (OR 1.648; 95% CI 1.167–2.327; P = 0.005) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for the association of clinical variables with the risk of coronary PP

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age, per 1 year | 1.031 (1.016–1.047) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1.490 (1.129–1.967) | 0.005 |

| Systolic BP, per 1 mmHg | 1.012 (1.003–1.022) | 0.012 |

| Diastolic BP, per 1 mmHg | 1.013 (0.999–1.027) | 0.079 |

| BMI, per 1 kg/m2 | 1.077 (1.026–1.130) | 0.003 |

| Total cholesterol, per 1 mg/dL | 0.998 (0.995–1.002) | 0.393 |

| Triglyceride, per 1 mg/dL | 1.002 (1.000–1.004) | 0.021 |

| HDL-C, per 1 mg/dL | 0.987 (0.976–0.998) | 0.017 |

| LDL-C, per 1 mg/dL | 0.998 (0.994–1.002) | 0.288 |

| FBG, per 1 mg/dL | 1.009 (1.004–1.014) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, per 1% | 1.198 (0.986–1.456) | 0.069 |

| TyG index tertiles | ||

| I (lowest) | 1 | – |

| II | 1.294 (0.932–1.797) | 0.123 |

| III (highest) | 1.648 (1.167–2.327) | 0.005 |

BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, CI confidence interval, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR, odds ratio; TyG, triglyceride glucose

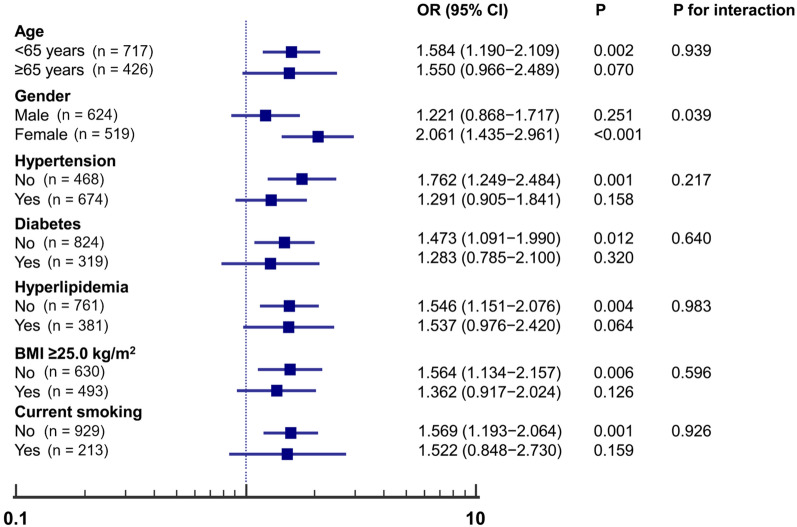

Subgroup analysis for the relationship of TyG index with coronary PP

Figure 2 shows the subgroup analysis of the estimated OR of TyG index for coronary PP. The TyG index was significantly associated with an increased risk of PP in subgroups of aged < 65 years (OR 1.584; 95% CI 1.190–2.109; P = 0.002), females (OR 2.061; 95% CI 1.435–2.961; P < 0.001), as well as those without hypertension (OR 1.762; 95% CI 1.249–2.484; P = 0.001), and diabetes (OR 1.473; 95% CI 1.091–1.990; P = 0.012). The same association was observed with hyperlipidemia (OR 1.546; 95% CI 1.151–2.076; P = 0.004), BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 (OR 1.564; 95% CI 1.134–2.157; P = 0.006), and current smoking status (OR 1.569; 95% CI 1.193–2.064; P = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Subgroup analysis for the impact of TyG index on coronary PP. TyG triglyceride glucose, PP plaque progression

TyG index on the risk of coronary PP

The results of multiple logistic regression models for the association between TyG index and PP risk are presented in Table 4. Increased TyG index values were significantly related to an increased risk of PP after adjusting for other confounding variables. After adjusting for traditional CV risk factors, TyG index was associated with coronary PP (OR 1.308; 95% CI 1.004–1.703; P = 0.046) (Additional file 1: Table S1). TyG index was particularly associated with the calcified PP among coronary plaque sub-types (Additional file 2: Table S2). Regarding rapid coronary PP, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the risk of rapid PP was increased in group III (OR 1.557; 95% CI 1.109–2.185; P = 0.011) compared with group I (Table 5).

Table 4.

Multiple logistic models for the impact of TyG index on coronary PP

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TyG index, per 1-unit increase | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.575 (1.232–2.015) | < 0.001 | 1.103 (1.049–1.160) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.598 (1.250–2.042) | < 0.001 | 1.111 (1.056–1.169) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.409 (1.062–1.869) | 0.017 | 1.083 (1.021–1.150) | 0.008 |

BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, CI confidence interval, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, OR odds ratio, PP plaque progression, RR relative risk, TyG triglyceride glucose

Model 1: Unadjusted

Model 2: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 3: Adjusted for age, sex, systolic BP, BMI, and HDL-C

Table 5.

Association of TyG index and traditional risk factors with rapid PP

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 1.836 (1.412–2.387) | < 0.001 | 1.717 (1.309–2.253) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1.248 (0.962–1.620) | 0.095 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.561 (1.193–2.044) | 0.001 | 1.292 (0.976–1.710) | 0.074 |

| Diabetes | 1.845 (1.399–2.432) | < 0.001 | 1.509 (1.125–2.023) | 0.006 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.468 (1.124–1.919) | 0.005 | 1.340 (1.019–1.763) | 0.036 |

| BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 | 1.120 (0.863–1.454) | 0.393 | ||

| TyG index tertiles | ||||

| I (lowest) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| II | 1.362 (0.983–1.887) | 0.063 | 1.242 (0.890–1.734) | 0.202 |

| III (highest) | 1.777 (1.288–2.451) | < 0.001 | 1.557 (1.109–2.185) | 0.011 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; OR, odds ratio; PP, plaque progression; TyG, triglyceride glucose

Discussion

Main findings

To the best our knowledge, this is first study to evaluate the longitudinal quantitative changes of coronary plaques and their subtypes related to TyG index using serial CCTA. This study identified a significant association between TyG index and coronary atherosclerosis progression. Previous cross-sectional studies have reported a significant relationship between TyG index and CAC prevalence [8, 9]. A recent longitudinal study revealed that elevated TyG index is independently associated with CAC progression [21]. However, this study had a retrospective design and included only a Korean population, which were limitations. Additionally, considering that non-calcified plaques might be related to an increased risk of acute coronary syndrome events [22], it might be important to compare longitudinal changes of non-calcified plaques according to TyG index values. In the present PARADIGM study, which had a prospective, international, and observational design, we identified that the baseline total PV and all subtypes as well as annualized change in total, fibrous, and dense-calcium PV increased with increasing TyG index values. In addition, the TyG index had a positive association with the annual change of total PV, TAVnorm, and PAVtotal (Additional file 3: Table S3). Even after adjusting for confounding factors, TyG index was related to the increased risk of PP as well as rapid PP. Regarding coronary plaque sub-types, TyG index was found to be associated with calcified PP after adjusting for traditional CV risk factors in a previous cross-sectional cohort study [9].

Recent investigations on the longitudinal assessment of coronary atherosclerosis

To understand that the coronary atherosclerotic change is an important issue in clinical practice, it is well-known that diabetes has close association with the prevalence and severity of CCTA verified CAD progression [23]. Even asymptomatic diabetic patients experience plaque progression as well as evolution to overt or silent CAD, and an increase in the PV was reported to be associated with subsequent CV events [24]. In addition, the increased duration of diabetes combined with higher HbA1c levels deleteriously influences culprit-plaque characteristics among diabetic patients who suffered acute myocardial infarction [25]. A rapid plaque progression was specially observed in male patients and in patients with typical angina [26]. While helical flow in coronary arteries has a protective role against atherosclerotic wall thickness growth [27], an intrinsic calcification angle, defined as the angle externally projected by a vascular calcification, is a novel feature of coronary plaque vulnerability and its impact on fibrous cap stress is potentiated in more superficial calcifications, adding to the destabilizing role of smaller calcifications [28].

Focused issue for the significance of TyG index

It is well-established that IR is a main mechanism in the development of type 2 diabetes. A previous PARADIGM study identified that individuals with established diabetes experienced greater PP, particularly, significantly greater progression of adverse plaque formation than those without diabetes [29]. In addition, unlike diabetes, pre-diabetic condition was not independently associated with coronary PP in the sub-study of same registry [30]; however, although pre-diabetes was defined according to the criteria used in previous studies, glycemic status was assessed based on only the levels of FBG and HbA1c without considering IR status among non-diabetic participants. According to the results of a recent large cross-sectional cohort study [31], TyG index had an independent and positive association with the risk of CAD and obstructive CAD in non-diabetic individuals; however, glycemic control status reflected in HbA1c rather than IR parameters was significantly related to the risk of both CAD and obstructive CAD in individuals with established diabetes. These results might support the hypothesis for the different pathogenesis of CAD according to diabetic status. In clinical practice, atherosclerosis-related adverse events commonly occurred even in people with low CV risk burden [32–34]. Thus, early detection of the presence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in this population is important. Recent studies have focused on defining useful predictors for subclinical atherosclerosis in individuals with low CV risk [35, 36]. Interestingly, although the statistical significance could be influenced by the sample size of the individual subgroup, this study showed that TyG index had a significant predictive value for PP in individuals without the traditionally known CV risk factors, especially in female subgroup. This result suggests that TyG index is a potential surrogate marker for the early detection of subclinical atherosclerosis in the absence of CV risk factors as reported in a recent cross-sectional cohort study [37]. Considering the pivotal role of IR in atherosclerosis progression by promoting apoptosis of macrophages, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells [38–40], further prospective studies with larger sample sizes will be necessary to address the predictive value of TyG index for subclinical atherosclerosis in individuals with low CV risk burden.

Limitations

There are some limitations in the present study. First, we only evaluated the association between baseline TyG index and coronary atherosclerotic change; longitudinal consecutive changes of TyG index during follow-up could not be confirmed. Second, the effects of anti-hypertensive and anti-diabetic medications were not controlled for because of the observational nature of the study design. Third, the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance was not analyzed and compared with TyG index because insulin levels were not measured in the PARADIGM registry. Fourth, we could not confirm the TyG index of the small coronary arteries in the present study. Fifth, a selection bias might be present because of the retrospective inclusion of participants. In addition, the results of CCTA at baseline could affect the performance of follow-up CCTA. Finally, despite our application of strict and standardized criteria for assessing CCTA, atherosclerotic findings can be affected by HU density. Despite these limitations, this study used serial CCTA to estimate coronary PVC and PP according to TyG index values in a large multicultural cohort subjects.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates the independent association between TyG index values and coronary PP based on serial quantitative assessment by CCTA during a relatively short-term period. Further large prospective and randomized studies with longer follow-up durations are necessary to confirm the results of the present study.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Clinical variables and annualized total PVC.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for the association of clinical variables with coronary plaque progression.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Association of clinical variables with the annual change of total PV, TAVnorm, and PAVtotal.

Acknowledgements

The Medical Information Center of Ulsan University Hospital supported this work in terms of statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- ACEI

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- BMI

Body mass index

- BP

Blood pressure

- CV

Cardiovascular

- CAC

Coronary artery calcification

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CCTA

Coronary computed tomography angiography

- CI

Confidence interval

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- IR

Insulin resistance

- LCL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- OR

Odds ratio

- PVC

Plaque volume change

- RR

Relative risk

- PARADIGM

Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography IMaging

- PAVtotal

Total percent atheroma volume

- PP

Plaque progression

- TAVnorm

Normalized total atheroma volume

- TyG

Triglyceride glucose

Authors’ contributions

KBW, HBP, RH, and HJC contributed to the conception or design of the work. KBW, BKL, HBP, RH, SEL, AR, FYL, AK, MH, YJK, JMS, EC, DA, GP, MJB, IG, EJC, FC, EM, HM, PAG, JAL, SS, JHC, RV, HS, KC, GLR, PHS, DSB, JN, LJS, JJB, JKM, and HJC contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. KBW and BKL drafted the manuscript. HJC critically revised the manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the manuscript to ensure integrity and accuracy. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Leading Foreign Research Institute Recruitment Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (Grant No. 2012027176).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by ethics committee of each institution, and informed consent for the procedure was obtained from each participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. James K. Min receives funding from the Dalio Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and GE Healthcare. Dr. Min serves on the scientific advisory board of Arineta and GE Healthcare, and has a clear equity interest. Dr. Habib Samaday has equity interest in Covanos. All other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ki-Bum Won and Byoung Kwon Lee contributed equally to the manuscript’s preparation

Contributor Information

Ki-Bum Won, Email: kbwon99@naver.com.

Byoung Kwon Lee, Email: cardiobk@yuhs.ac.

Hyung-Bok Park, Email: hyungbok7@gmail.com.

Ran Heo, Email: ran.heo.md@gmail.com.

Sang-Eun Lee, Email: tkddmss@gmail.com.

Asim Rizvi, Email: drasimrizvi@gmail.com.

Fay Y. Lin, Email: fayylin@gmail.com

Amit Kumar, Email: amit.kumar.800004@gmail.com.

Martin Hadamitzky, Email: hadamitzky@gmail.com.

Yong-Jin Kim, Email: kimdamas67@gmail.com.

Ji Min Sung, Email: JMSUNG@yuhs.ac.

Edoardo Conte, Email: edoardo.conte86@gmail.com.

Daniele Andreini, Email: daniele.andreini@cardiologicomonzino.it.

Gianluca Pontone, Email: gianluca.pontone@ccfm.it.

Matthew J. Budoff, Email: mbudoff@labiomed.org

Ilan Gottlieb, Email: ilangottlieb@gmail.com.

Eun Ju Chun, Email: humandr.eunju@gmail.com.

Filippo Cademartiri, Email: filippocademartiri@gmail.com.

Erica Maffei, Email: ericamaffei@gmail.com.

Hugo Marques, Email: hmarques@hospitaldaluz.pt.

Pedro de Araújo Gonçalves, Email: pgoncalves@hospitaldaluz.pt.

Jonathon A. Leipsic, Email: jleipsic@providencehealth.bc.ca

Sanghoon Shin, Email: nephilla99@gmail.com.

Jung Hyun Choi, Email: mariahyeon@gmail.com.

Renu Virmani, Email: rvirmani@cvpath.org.

Habib Samady, Email: hsamady@emory.edu.

Kavitha Chinnaiyan, Email: kchinnaiyan@beaumont.edu.

Gilbert L. Raff, Email: graff@beaumont.edu

Peter H. Stone, Email: pstone@partners.org

Daniel S. Berman, Email: Daniel.Berman@cshs.org

Jagat Narula, Email: narula@mountsinai.org.

Leslee J. Shaw, Email: lshaw3@emory.edu

Jeroen J. Bax, Email: J.J.Bax@lumc.nl

James K. Min, Email: jkm2001@med.cornell.edu

Hyuk-Jae Chang, Email: hjchang@yuhs.ac.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12933-020-01081-w.

References

- 1.Smith SC, Jr, Jackson R, Pearson TA, Fuster V, Yusuf S, Faergeman O, Wood DA, Alderman M, Horgan J, Home P, Hunn M, Grundy SM. Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum. Circulation. 2004;109(25):3112–3121. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanley AJ, Williams K, Stern MP, Haffner SM. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in relation to the incidence of cardiovascular disease: the San Antonio Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1177–1184. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Meigs JB, Bonadonna RC, Muggeo M. Insulin resistance as estimated by homeostasis model assessment predicts incident symptomatic cardiovascular disease in caucasian subjects from the general population: the Bruneck study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):318–324. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eddy D, Schlessinger L, Kahn R, Peskin B, Schiebinger R. Relationship of insulin resistance and related metabolic variables to coronary artery disease: a mathematical analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):361–366. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simental-Mend´ıa LE, Rodr´ıguez-Mor´an M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6(4):299–304. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasques AC, Novaes FS, de Oliveira MDAS, Souza JR, Yamanaka A, Pareja JC, et al. TyG index performs better than HOMA in a Brazilian population: a hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(3):e98–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrero-Romero F, Villalobos-Molina R, Jim´enez-Flores JR, Simental-Mendia LE, Méndez-Cruz R, Murguía-Romero M, Rodríguez-Morán M. Fasting triglycerides and glucose index as a diagnostic test for insulin resistance in young adults. Arch Med Res. 2016;47(5):382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MK, Ahn CW, Kang S, Nam JS, Kim KR, Park JS. Relationship between the triglyceride glucose index and coronary artery calcification in Korean adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0589-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Won KB, Kim YS, Lee BK, Heo R, Han D, Lee JH, Lee SE, Sung JM, Cho I, Park HB, Cho IJ, Chang HJ. The relationship of insulin resistance estimated by triglyceride glucose index and coronary plaque characteristics. Medicine. 2018;97(21):e10726. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, Scherer M, Bellinger R, Martin A, Benton R, Delago A, Min JK. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(21):1724–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, van Mieghem CA, Nieman K, van Werkhoven JM, Pundziute G, Weustink AC, de Vos AM, Pugliese F, Rensing B, Jukema JW, Bax JJ, Prokop M, Doevendans PA, Hunink MG, Krestin GP, de Feyter PJ. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2135–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow BJ, Small G, Yam Y, Chen L, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan KM, Delago A, Dunning A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Lin F, Maffei E, Raff GL, Shaw LJ, Villines TC, Min JK. Incremental prognostic value of cardiac computed tomography in coronary artery disease using CONFIRM: COroNary Computed Tomography Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: an InteRnational Multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(5):463–472. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.964155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJ, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines T, Berman DS. Age- and sex related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(8):849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SE, Chang HJ, Rizvi A, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ, Conte E, Andreini D, Pontone G, Volpato V, Budoff MJ, Gottlieb I, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Marques H, Leipsic JA, Shin S, Choi JH, Chung N, Min JK. Rationale and design of the Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography IMaging (PARADIGM) registry: a comprehensive exploration of plaque progression and its impact on clinical outcomes from a multicenter serial coronary computed tomographic angiography study. Am Heart J. 2016;182:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GJ, Nieman K, Pontone G, Raff GL. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8(5):342–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbara S, Blanke P, Maroules CD, Cheezum M, Choi AD, Han BK, Marwan M, Naoum C, Norgaard BL, Rubinshtein R, Schoenhagen P, Villines T, Leipsic J. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: Endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(6):435–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Graaf MA, Broersen A, Kitslaar PH, Roos CJ, Dijkstra J, Lelieveldt BP, Jukema JW, Schalij MJ, Delgado V, Bax JJ, Reiber JH, Scholte AJ. Automatic quantification and characterization of coronary atherosclerosis with computed tomography coronary angiography: cross-correlation with intravascular ultrasound virtual histology. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(5):1177–1190. doi: 10.1007/s10554-013-0194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achenbach S, Moselewski F, Ropers D, Ferencik M, Hoffmann U, MacNeill B, Pohle K, Baum U, Anders K, Jang IK, Daniel WG, Brady TJ. Detection of calcified and non-calcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque by contrast-enhanced, submillimeter multidetector spiral computed tomography a segment-based comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2004;109(1):14–17. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111517.69230.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholls SJ, Hsu A, Wolski K, Hu B, Bayturan O, Lavoie A, Uno K, Tuzcu EM, Nissen SE. Intravascular ultrasound-derived measures of coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden and clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(21):2399–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han D, Kolli KK, Al’Aref SJ, Baskaran L, van Rosendael AR, Gransar H, Andreini D, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Chinnaiyan K, Choi JH, Conte E, Marques H, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Gottlieb I, Hadamitzky M, Leipsic JA, Maffei E, Pontone G, Raff GL, Shin S, Kim YJ, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Sung JM, Lee SE, Virmani R, Samady H, Stone P, Narula J, Berman DS, Bax JJ, Shaw LJ, Lin FY, Min JK, Chang HJ. Machine learning framework to identify individuals at risk of rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis: from the PARADIGM registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(5):e013958. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park K, Ahn CW, Lee SB, Kang S, Nam JS, Lee BK, Kim JH, Park JS. Elevated TyG index predicts progression of coronary artery calcification. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1569–1573. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomsen C, Abdulla J. Characteristics of high-risk coronary plaques identified by computed tomographic angiography and associated prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(2):120–129. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi R, Shi K, Yang ZG, Guo YK, Diao KY, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Huang S. Serial coronary computed tomography angiography-verified coronary plaque progression: comparison of stented patients with or without diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0924-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Dou G, Tesche C, De Cecco CN, Jacobs BE, Schoepf UJ, Chen Y. Progression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden and relationship with adverse cardiovascular event in asymptomatic diabetic patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1016-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheng Zhaoxue, Zhou Peng, Liu Chen, Li Jiannan, Chen Runzhen, Zhou Jinying, Song Li, Zhao Hanjun, Yan Hongbing. Relationships of coronary culprit-plaque characteristics with duration of diabetes mellitus in acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular optical coherence tomography study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber C, Deseive S, Brim G, Stocker TJ, Broersen A, Kitslaar P, Martinoff S, Massberg S, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J. Coronary plaque volume and predictors for fast plaque progression assessed by serial coronary CT angiography—a single-center observational study. Eur J Radiol. 2020;123:108805. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Nisco G, Hoogendoorn A, Chiastra C, Gallo D, Kok AM, Morbiducci U, Wentzel JJ. The impact of helical flow on coronary atherosclerotic plaque development. Atherosclerosis. 2020;300:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reith S, Milzi A, Lemma ED, Dettori R, Burgmaier K, Marx N, Burgmaier M. Intrinsic calcification angle: a novel feature of the vulnerable coronary plaque in patients with type 2 diabetes: an optical coherence tomography study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0926-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim U, Leipsic JA, Sellers SL, Shao M, Blanke P, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ, Conte E, Andreini D, Pontone G, Budoff MJ, Gottlieb I, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Marques H, Shin S, Choi JH, Virmani R, Samady H, Stone PH, Berman DS, Narula J, Shaw LJ, Bax JJ, Min JK, Chang HJ. Natural history of diabetic coronary atherosclerosis by quantitative measurement of serial coronary computed tomographic angiography: results of the PARADIGM Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(10):1461–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Won KB, Lee SE, Lee BK, Park HB, Heo R, Rizvi A, Lin FY, Kumar A, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ, Sung JM, Conte E, Andreini D, Pontone G, Budoff MJ, Gottlieb I, Chun EJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Marques H, Leipsic JA, Shin S, Choi JH, Virmani R, Samady H, Chinnaiyan K, Raff GL, Stone PH, Berman DS, Narula J, Shaw LJ, Bax JJ, Min JK, Chang HJ. Longitudinal assessment of coronary plaque volume change related to glycemic status using serial coronary computed tomography angiography: a PARADIGM (Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography Imaging) substudy. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13(2):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho YR, Ann SH, Won KB, Park GM, Kim YG, Yang DH, Kang JW, Lim TH, Kim HK, Choe J, Lee SW, Kim YH, Kim SJ, Lee SG. Association between insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and coronary artery disease according to the presence of diabetes. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6129. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Islam S, Li W, Liu L, Bo J, Lou Q, Lu F, Liu T, Yu L, Zhang S, Mony P, Swaminathan S, Mohan V, Gupta R, Kumar R, Vijayakumar K, Lear S, Anand S, Wielgosz A, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, Yusoff K, Ismail N, Iqbal R, Rahman O, Rosengren A, Yusufali A, Kelishadi R, Kruger A, Puoane T, Szuba A, Chifamba J, Oguz A, McQueen M, McKee M, Dagenais G. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):818–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, Budoff MJ, Blankstein R, Sibley CT, Agatston A, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(33):2232–2241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Friera L, Fuster V, López-Melgar B, Oliva B, García-Ruiz JM, Mendiguren J, Bueno H, Pocock S, Ibáñez B, Fernández-Ortiz A, Sanz J. Normal LDL-cholesterol levels are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in the absence of risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):2979–2991. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Won KB, Park GM, Yang YJ, Ann SH, Kim YG, Yang DH, Kang JW, Lim TH, Kim HK, Choe J, Lee SW, Kim YH, Kim SJ, Lee SG. Independent role of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(8):866–872. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jez091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park GM, Cho YR, Won KB, Yang YJ, Park S, Ann SH, Kim YG, Park EJ, Kim SJ, Lee SG, Yang DH, Kang JW, Lim TH, Kim HK, Choe J, Lee SW, Kim YH. Triglyceride glucose index is a useful marker for predicting subclinical coronary artery disease in the absence of traditional risk factors. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-1187-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bornfeldt KE, Tabas I. Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sung KC, Wild SH, Kwag HJ, Byrne CD. Fatty liver, insulin resistance, and features of metabolic syndrome: relationships with coronary artery calcium in 10,153 people. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(11):2359–2364. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reardon CA, Lingaraju A, Schoenfelt KQ, Zhou G, Cui C, Jacobs-El H, Babenko I, Hoofnagle A, Czyz D, Shuman H, Vaisar T, Becker L. Obesity and insulin resistance promote atherosclerosis through an IFNg-regulated macrophage protein network. Cell Rep. 2018;23(10):3021–3030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Clinical variables and annualized total PVC.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for the association of clinical variables with coronary plaque progression.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Association of clinical variables with the annual change of total PV, TAVnorm, and PAVtotal.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.