Abstract

The novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 and has created a medical emergency worldwide. In India, it is already reported more than 855 thousand cases and more than 22 thousands deaths due to COVID-19 till July 12, 2020. The role of temperature, humidity, and absolute humidity in the transmission of COVID-19 has not yet been well established. In contrast, for the previous many viral infections like influenza, it is well established. Therefore the study to investigate the meteorological condition for incidence and spread of COVID-19 infection and to provide a scientific basis for prevention and control measures against the new disease is required for India. In this work, we analyze daily averaged meteorological data for the last three years (2017–2019) for March, April and May months and the same for the year 2020 for March 1 to May 31. We found a positive association between daily COVID-19 cases and temperature and a mixed association with relative and absolute humidity over India. We have investigated the association of aerosols (AOD) and other pollutions (NO2) with COVID-19 cases during the study period and also during the lockdown period (25 March-31 May) in India. During the lockdown period, aerosols (AOD) and NO2 reduced sharply with a maximum percentage drop of about 60 and 45, respectively. We have also found the reduction in surface PM2.5 PM10 and NO2 for the six mega cities of India during the lockdown period. Our results suggest that COVID-19 still may spread in warm, humid regions or during summer/monsoon, therefore an effective public health intervention should be implemented across India to slow down the transmission of COVID-19.

Keywords: Novel Coronavirus, India, Summer, COVID-19, Pandemic, Absolute humidity

Graphical abstract

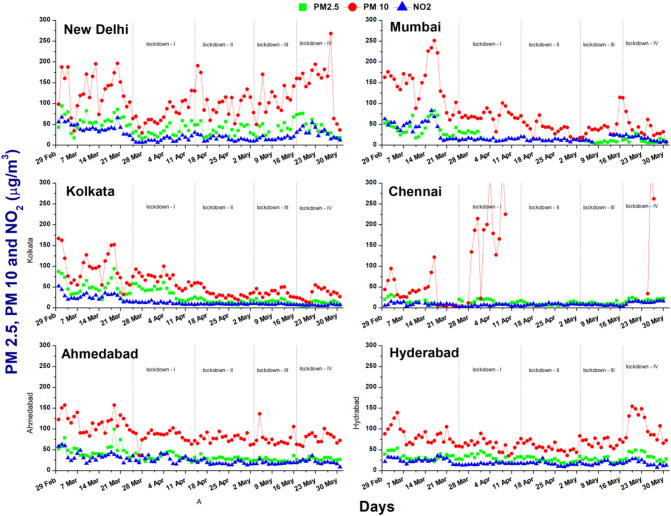

Variability of surface PM2.5, PM10 and NO2 at six mega cities of India during lockdown (1 March-31 May 2020).

Highlights

-

•

First study on the effects of meteorological factors on COVID-19 cases in India

-

•

A positive association between daily new cases of COVID-19 with temperature

-

•

RH and AH show mixed association with daily new cases of COVID-19.

-

•

Early lockdown in India slows down the spread of contagious disease COVID-19.

-

•

More than 45% fall was found in AOD and NO2 values during the lockdown period.

1. Introduction

The novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) was identified in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020) and caused over 12.80 million cases and over 570 thousands deaths worldwide till date (12 July 2020) (Worldometer). It has spread rapidly to several countries and has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020 (WHO). In India, it is already reported more than 855 thousands cases and more than 22 thousands deaths due to Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (COVID/Tracker). Previous studies have supported an epidemiological hypothesis that cold and dry (low absolute humidity) environments facilitate the survival and spread of droplet-mediated viral diseases. Warm and humid (high absolute humidity) environments see attenuated viral transmission like influenza and SARS (Schoeman and Fielding, 2019). As this coronavirus appeared for the first time and was highly contagious, it poses a great challenge to diagnosis and prevention and control. Human coronaviruses have been associated with a wide spectrum of respiratory diseases in different studies and belong to the Coronaviridae family (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020; Weiss and Navas-Martin, 2005). It has been suggested that flu viruses are not easily transmitted in hot and humid conditions. Similar comments about the COVID-19 have repeatedly been made by health officials as well as world leaders that the outbreak will slow down by summer, due to decreased transmissivity (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020). Wang et al. (2020) also found a similar result in his model study. They suggested that during the coming summer in the northern hemisphere, the spread of Coronavirus will be reduced in tropical regions. It is also important to note that SARS-Cov, which is a type of coronavirus, loses its ability to survive in higher temperatures, which may be due to the breakdown of their lipid layer at higher temperatures (Schoeman and Fielding, 2019). However, no seasonality has been established for COVID-19.

Bukhari and Jameel (2020) reported that in the beginning none of the Asian, Middle Eastern and South American countries had implemented drastic quarantine measures such as those in China, Europe, and some US states, however, their overall growth rate was lower, but now the rate is much similar to the Europe and USA. He suggested that it could be due to a lower number of testing, such as in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and African countries. Many countries such as Singapore, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Qatar, Taiwan, and Hong Kong have performed more 2019-nCoV tests per million people than the USA, Italy, and several European countries. It was suggested that non-testing was not an issue, at least for the tropical countries.

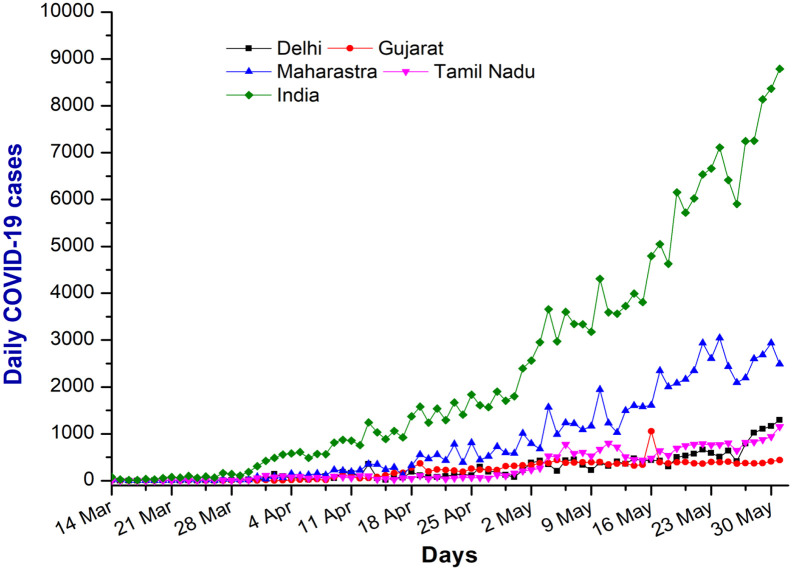

At the beginning of April, thousands of new cases have been documented in regions with Tem >18 °C, suggesting that the role of warmer temperature in slowing the spread of the COVID-19, as suggested earlier, might only be observed, at much higher temperatures. Unlike temperature, most of the COVID-19 cases were reported in the range of AH has consistently been between 3 and 9 g/m3 (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020). Bukhari and Jameel (2020) also suggested that if, new cases in April and May continue to cluster within the observed range of AH, i.e., 3 to 9 g/m3, then the countries experiencing monsoon, i.e., having high absolute humidity (>10 g/m3) may see a slowdown in transmissions, due to climatic factors. But for India, it is not true as many states having high temperate and high humidity are still leading in COVID-19 cases in India like Maharashtra, Delhi and Tamil Nadu (Fig. 1 ) as for India, the average AH, is between 8 and 11 g/m3 during March and April and some times more than 15 g/m3 in month of May (Fig. 4). A higher number of cases also reported for Kerala at the beginning of April, but government early mitigation strategies controlled the daily new COVID-19 cases.

Fig. 1.

Top four states and India in total confirmed daily COVID-19 cases from 14 March-31 May 2020, different colors represent different states. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

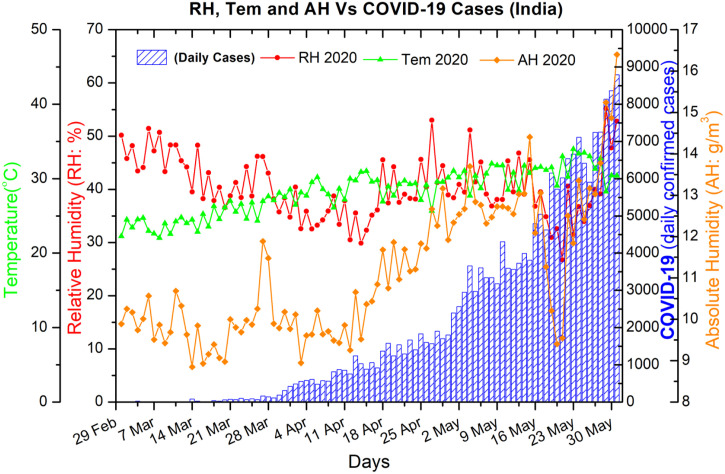

Fig. 4.

Diurnal variations of surface temperatures, relative humidity, and absolute humidity vs. daily confirmed COVID-19 cases for the Indian region for 1 March-31 May 2020.

Since 30 January 2020, after the first case was reported in India, the increasing number of cases caused by COVID-19 had been identified until February. Up to the second week of March, only cases which were coming from foreign or in contact with them were reported, but after 15th March, new daily cases appeared with no foreign travel cases. The number shoots up after 25th March when a community in Delhi was reported that they might have COVID positive cases with at least 2000 people. After this event, an increasing number of daily cases continue with those who have contact with these peoples. Presently more than 25 thousand confirm cases are reported daily in India. On March 25, 2020, India, the residence of more than 1.38 billion humans, was forced to shut down both outbound and inbound traffic to contain the COVID-19 outbreak. Lockdown was implemented in 4 stages in India, first lockdown was from 25th March to 14th April, second was from 15th April to 3rd May, third was from 4th May to 17th May and last the fourth lockdown was from 18th May to 31st May 2020. After this period there was onlock-1 from 1st June to 30th June and unlock-2 from 1st July to 31st July.

In addition to population mobility and human-to-human contact, environmental factors can impact droplet transmission and survival of viruses (e.g., influenza) but have not yet been examined for this novel pathogen for Indian cases. Absolute humidity, defined as the water content in ambient air, is a strong environmental determinant of other viral transmissions (Barreca and Shimshack, 2012; Luo et al., 2020). For example, influenza viruses survive longer on surfaces or in droplets in cold and dry air - increasing the likelihood of subsequent transmission. Thus, it is key to understand the effects of environmental factors on the ongoing outbreak to support decision-making about disease control, especially in locations where the risk of transmission may have been underestimated, such as in humid and warmer locations. We examine variability in Temperature (Tem), relative humidity (RH), and absolute humidity (AH) and transmission of COVID-19 across India. We show that the observed patterns of COVID-19 are not completely consistent with the hypothesis that high AH may limit the survival and transmission of this new virus.

Bu et al. (2020) found from a global perspective, cities with a mean temperature below 24 °C are all high-risk cities for 2019-nCoV transmission before June. In our case, it is not true as in India; the temperature was always high when the COVID-19 growth rate is high. Few studies supporting the hypothesis that high temp and high humidity will reduce the case like, Wang et al. (2020) find in their study, under a linear regression framework, high temperature and high humidity significantly reduces the transmission of COVID-19. They reported that a one-degree Celsius increase in temperature and a 1% increase in relative humidity lower R by 0.0225 and 0.0158, respectively. The transmission of coronaviruses can be affected by several factors, including climate conditions (such as temperature and humidity), population density, and medical care quality (Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding the relationship between weather and the transmission of COVID-19 is the key to forecast the intensity and end time of this pandemic.

The number of 2019-nCoV cases detected in a country/state depends on multiple factors, including testing, population (density), community structure, social dynamics, governmental policies, global connectivity, air and surface life, reproduction number, and serial interval of the virus. Many of this information regarding 2019-nCoV are still emerging, such as the virus being airborne for more than 3 h and having very different survival times on metals, cardboards and plastics (van Doremalen et al., 2020). Recently WHO also communicated that COVID-19 may transmit via aerosols in the closed environments, which was our main highlight in our previous version of the manuscript. The behavior of 2019-nCoV with meteorological parameters and with aerosols is still under investigation and also the subject of this paper over the Indian region during its spread and during the different lockdown period (25 March-31 May 2020). The analysis presented in this paper provides a direct comparison between the spread of COVID-19 virus and local environmental conditions over Indian region and study the growth rate of COVID-19 among different states of India (Fig. 1).

2. Data and methodology

In our study, we have used COVID-19 data of daily conformed cases, surface temperature and surface humidity, aerosol optical depth (AOD), particulate matter (PM) and NO2 with daily averages time series data for the Indian region. Following data were used,

2.1. Epidemiological data

The daily number of confirmed cases of patients infected with COVID-19 was taken from the WHO website and other public sources like Worldometer (Worldometer) and COVID-19Tracker/India (https://www.covid19india.org/) (COVID/Tracker) for March, April and May 2020.

2.2. Weather data

The meteorological parameters during the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in India for 2020 and three year past data were collected and analyzed. Air temperature and relative humidity data were taken from Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) onboard EOS Aqua. Daily Data were taken for the surface temperature and surface relative humidity for the Indian region with resolution 1 degree for days March 1 to May 31, 2020, and for 2017–2019 from 1 March to 31 May. We have calculated the absolute humidity using these two parameters using the Clausius Clapeyron equation (Bolton, 1980) as follows:

| (1) |

where AH is the absolute humidity, and T is the temperature in degrees C.

2.3. AOD and pollutants data

Aerosols optical depth (AOD) and NO2 data were taken from GIOVANNI NASA (https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni/) sites from MODIS and OMI satellites. MODIS provides daily AOD data with the 1-degree resolution, which we used for the Indian region, and OMI also provides daily data with resolution 0.25 degrees. More details about MODIS data can be found elsewhere (Kumar et al., 2015). We have used data for 2017–2019 from March 1 to May 31 and 2020 from 1 March to 31 May. We have also used PM2.5, PM10 and NO2 data from CPCB station in different part of India for year 2020 (http://www.cpcb.gov.in/caaqm/).

2.4. HYSPLIT Trajectory data

HYSPLIT (NOAA) forward trajectories model was used to find out the surface air movement for the spread of aerosol.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Variability of COVID-19 cases with the meteorological parameters (temperature, humidity, and absolute humidity)

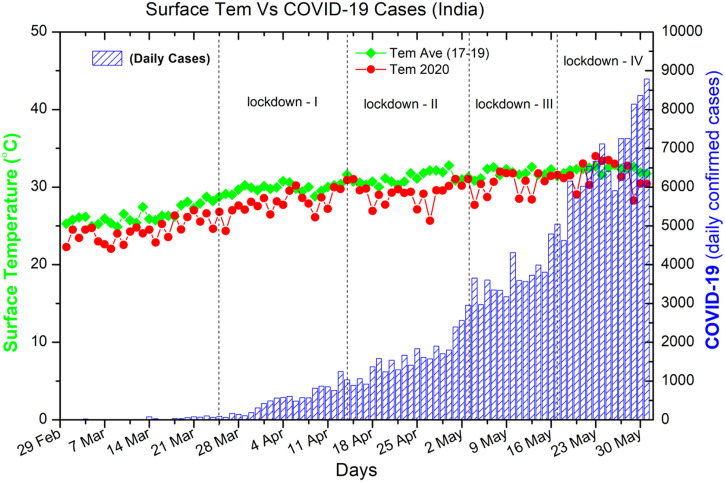

We look into the relation between daily temperature (Tem), Relative humidity (RH), and absolute humidity (AH) with the daily number of confirmed cases of corona patients in India. We have used daily averaged meteorological data for the last three years (2017–2019) for March, April and May month and the same for the year 2020 for March 1 to May 31. We have plotted the average Tem of the last three years (2017–2019) and Tem of the year 2020 for the March, April and May months with the daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 in India. We found that average temp of the last three years during March to May was varying from 24 to 34 °C, where this year Tem was underestimated from the last three years average Temp and varying from 22 to 32 °C till 20 May. Both Temp showing continuously increasing trends for March and April. A maximum number of new confirmed cases appeared during the lockdown and showing an almost continuous increasing trend, and this shows there is a positive association of the new confirmed cases of COVID-19 with the increasing Tem of the region (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Diurnal surface temperatures vs. daily confirmed COVID-19 cases for the Indian region for March, April and May months for average Tem (2017–2019) and 2020.

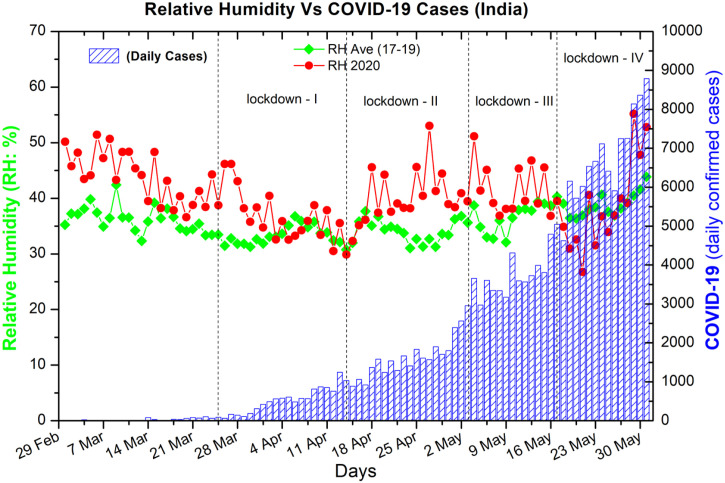

Similarly, we have plotted the RH value and daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 for average (2017–2019) and for 2020 for March, April and May months. We found a slowly decreasing trend in average RH varying from (42%–30%) till April and then increasing up to 45%in May, and for 2020 we found overestimating RH from average with range 55% to 32% till mid of May for India. RH values show the negative association with the daily confirm cases till mid of May then showing positive association (Fig. 3 ), which again showing that COVID-19 has no effect with the increasing humidity for India.

Fig. 3.

Same as Fig. 2 but for relative humidity.

Absolute humidity, the mass of water vapor per cubic meter of air, relates to both temperature and relative humidity. We have also investigated the relation of confirmed cases with AH. The AH vales vary from 9 to 11.5 g/m3 during March and mid-April months of 2020 and an increasing trend for mid-April to mid-May month, sometimes more than 15 g/m3 in month of May. We found that the new cases are low when AH vales are greater than 9.5 g/m3 and high cases and high death when AH vales are going low from 9.5 g/m3 up to mid of April month (Fig. 4 ), while AH is showing increasing trend from mid-April to mid of May months also COVID-19 case are in increasing trends. This indicated the high values for AH might be helpful to reduce the new cases in March and April months but not helpful in case of May. Still, it's not always true in Indian contest as the most affected states in India are Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, which are the coastal states and have high values of Tem and RH through March to April. Our results show some similarities to the other studies done earlier on COVID-19 cases in China, Europe, and the USA, but overall we found that high value of AH is not helpful to reducing the new COVID-19 cases for India.

Studying Wuhan, Guangzhou, and Beijing COVID-19 cased Bu et al. (2020) found a meteorological condition with the temperature between 13 and 19 °C and humidity between 50% and 80% was suitable for the survival and transmission of the coronavirus. They also speculated that from February to the end of May 2020, the areas ranging the temperature (13 °C–24 °C) are all key areas for disease prevention, especially densely populated cities; from June and after that, the disease in regions with a mean temperature over 24 °C will begin to subside. They suggested before June 2020, cities with a global average temperature below 24 °C are all under high-risk of the transmission of new coronaviruses. After June, the risk of disease transmission will be significantly reduced in the cities with a mean temperature reaching 24 °C or higher. Our results for the Indian case did not match with the hypothesis said above as average temperature for the Indian region for March, April and May was above 30 °C, even the COVID-19 cases were increasing rapidly in India even though restrict lockdown was there.

Based on their study of the spread of 2019-nCoV, Bukhari and Jameel (2020) hypothesize that the lower number of cases in tropical countries might be due to warm-humid conditions, under which the spread of the virus might be slower as has been observed for other viruses. They found that the relation between the number of 2019-nCoV cases and temperature and absolute humidity observed is strong; however, the underlying reasoning behind this relationship is still not clear. Similarly, they do not make clear that which environmental factor is more important. It could be that either temperature or absolute humidity is more important, or both may be equally or not important at all in the transmission of 2019-nCoV. The humidity dependency may be due to the less effective airborne nature of the viruses at higher absolute humidity, thus reducing the overall indirect transmission of 2019-nCoV at higher levels of humidity. Although higher humidity may increase the amount of virus deposited on surfaces, and virus survival time in droplets on surfaces, the reduction of the virus spread by indirect (through air) transmission may be the factor behind the reduced 2019-nCoV spread in the humid climate. These explanations are speculative and based on patterns observed for other coronaviruses. Urgent study/experiments on the association between coronavirus transmission against temperature and humidity in laboratories are needed to understand these associations.

3.2. Is COVID-19 airborne?

Many studies suggested that COVID-19 may be stable up to 3 h on aerosols (van Doremalen et al., 2020) and may be transmitted to long distances in a closed environment (Santarpia et al., 2020) as well as the open environment (Wang and Du, 2020). These studies suggest that COVID-19 may be airborne and can give a high risk of transmission through aerosols. Aerosols are particles formed by solid or liquid particles dispersed and suspended in the air. They contain soil particles, industrial dust particles, particulates emitted by automobiles, bacteria, microorganisms, plant spore powders, and other components. When a person who was infected with the virus, coughs, sneezes, breathes vigorously, or speaks loudly, the virus will be excreted from the body. It may dissolve with the aerosol and become the bio-aerosols. Bio-aerosols ranging in size from 1.0 to 5.0 μm generally remain in the air, whereas larger particles are deposited on surfaces. Droplets spread in the space of about 1 to 2 m from the source of infection. However, aerosol can travel hundreds of meters or more.

Wang and Du (2020), in his many case studies of COVID-19, speculated that the spread of the virus might be due to the aerosols because new patients in Inner Mongolia and Wuhan were never in direct contact with the confirmed cases. They found that COVID-19 may transmit through aerosol directly, but it needs to be further verified by experiments. If the aerosols can spread COVID-19, prevention and control will be much more difficult. Many of the information regarding 2019-nCoV are still emerging, such as the virus being airborne for more than 3 h and having very different survival times on metals, cardboards and plastics (van Doremalen et al., 2020). van Doremalen et al. (2020) found in his experiment that the COVID-19 virus can remain viable in aerosols throughout his experiment (3 h), similar to that observed with SARS-CoV-1. Santarpia et al. (2020) in their clinical study found that SARS-CoV-2 is shed during respiration, toileting, and fomite contact, indicating that infection may occur in both direct and indirect (through aerosols) contact. Although this study did not employ any size-fractionation techniques to determine the size range of SARS-CoV-2 droplets and particles, the data was suggestive that viral aerosol particles are produced by individuals that have the COVID-19 disease, even in the absence of cough. Therefore the COVID-19 may spread through the aerosols if the sufficient amount of aerosols is present in the environment. Also, the reduction in aerosol concentration during the lockdown may reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19 through aerosols. Recently WHO also announced that the risk of COVID-19 spread through aerosols are more in the closed environment places, which was already mentioned in our finding.

3.3. Association of COVID-19 with aerosols and pollutants in India

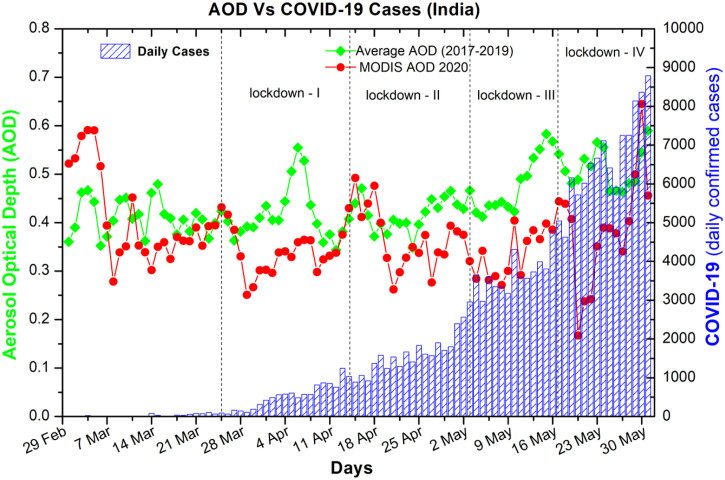

3.3.1. Association of COVID-19 with AOD

To prevent further spread of COVID-19, India has started the world's biggest lockdown of history on 25th March 2020, where the whole country was locked, and more than 1.38 billion people were forced to remain in their homes. This lockdown surely has positive feedback by less daily new COVID cases in March and April months compared to Europe and the USA and also affect the environment. Due to the strict lockdown in India, all public transport, industries, and individual activities were shut, which was reflected in air quality and aerosols over India. The aerosols decrease sharply over India in comparison with the average value of AOD of the last three years (Fig. 5 ). We have found a clear decrease in AOD value from the first day of lockdown with little increase in value in the coming days due to some relaxation in lockdown. Also, April month is harvest month so, aerosols are increased due to harvesting and crop residue burning in the April month, which can also be seen in averaged data. Now the lockdown (25 March-31 May) period is over, and the unlock period is going on with some relaxation in few important activities, so it may increase the aerosol concentration. During first lockdown there was everything shutdown so the reduction in AOD values are prominent, after first lockdown due to some relaxation AOD increased in second lockdown and in third and fourth it again decreased due to more wet removal and rain, but average value of 2017–2019 show a continues increasing trend during April and May. If the lockdown was followed strictly in stage 2–4, then a big reduction in AOD may be observed, which may restrict the risk of further new COVID-19 cases by its transmission through aerosols.

Fig. 5.

Diurnal variations of AOD vs. daily confirmed COVID-19 cases for the Indian region for March, April and May months for average AOD (2017–2019) and AOD for 2020.

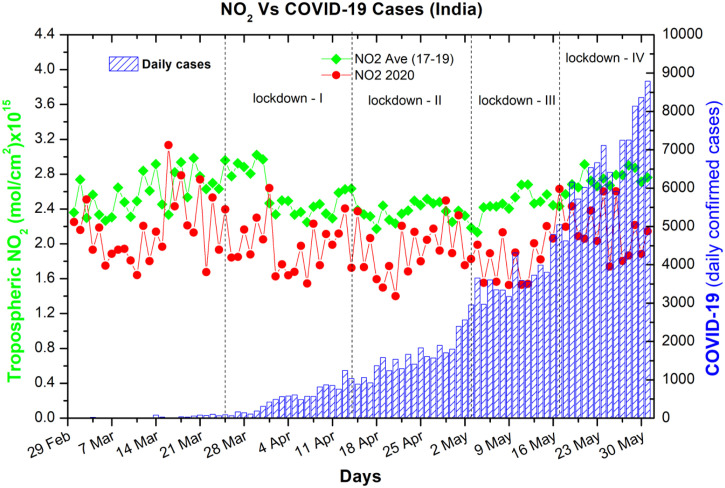

3.3.2. Association of COVID-19 with other pollutants like NO2

NO2 is a marker of the particulate matter (PM2.5) for the study of pollutions. Strict lockdown in India reduces the tropospheric column NO2 also, which again lowers the risk of COVID transmission through PM2.5 for the Indian region (Fig. 6 ). It's very clear from the plot that the concentration of NO2 is reduced after the lockdown in comparison to the three-year average value of NO2.

Fig. 6.

Same as Fig. 5 but for diurnal NO2.

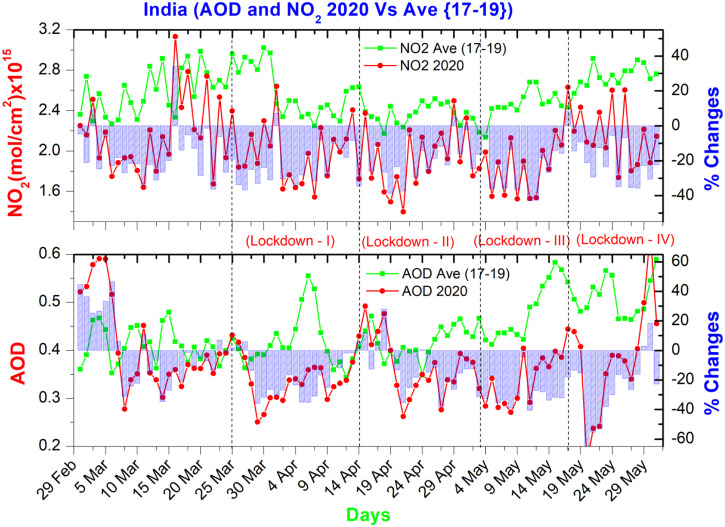

3.3.3. Percentage dropdown in pollutants concentration during the lockdown

Fig. 7 shows the percentage dropdown in the values of AOD and NO2 in comparison to the average value of the last three years over India. We found maximum dropdown during the lockdown period of 2020 up to 60% for AOD and 45% for NO2 in comparison to the average value of 2017–2019.

Fig. 7.

Percentage changes (column bar) in diurnal variations of AOD and NO2 for the Indian region for March, April and May months for average (2017–2019), and for 2020, the different lockdown periods are between dashed vertical lines.

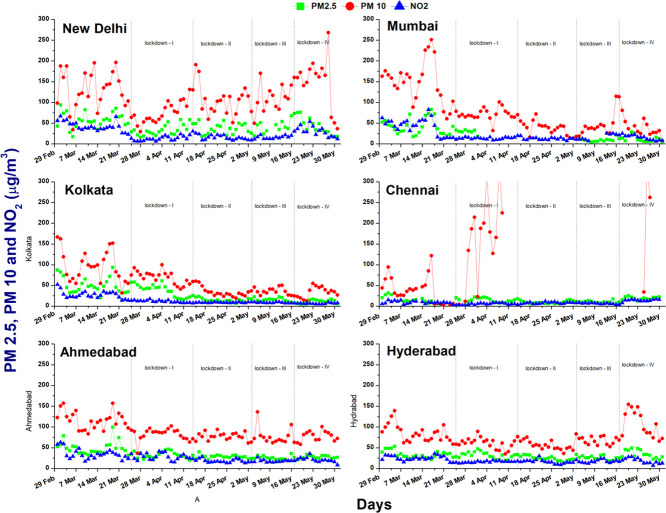

3.3.4. Study of air quality in different parts of India

We have also studied the air quality of six most COVID-19 affected mega cities of India like, New Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Ahmadabad, and Hyderabad during 1 March to 31 May 2020. We have plotted the daily average surface measurements of PM2.5, PM10 and NO2 for different cities of India (Fig. 8 ). We found a clear reduction in all the pollutants for all cities during the lockdown period. Only Delhi and Chennai showed some increasing values of PM10 in later part of lockdown which may be due to the dust activities and relaxation in lockdown.

Fig. 8.

Variability of surface PM2.5, PM10 and NO2 at six mega cities of India (1 March-31 May 2020).

3.4. Trajectory analysis of aerosols emitted at surface level

We have used the HYSPLIT trajectory model for calculation of the forward trajectory (not shown here) of surface aerosols. As van Doremalen et al. (2020) found in his study that COVID-19 virus can be stable at aerosols surface for about 3 h. So if a coronavirus is attached to the aerosols, then it may travel for longer distances and become airborne, this may be a reason for the high number of cases in the USA and other European countries as in early-stage they did consider COVID-19 may not transmit through the air and not using the face mask. So when we run HYSPLIT forward trajectory model for the surface level air for 3 h period, we found that in normal condition in April month in India, a surface level aerosol can travel up to 4 km distance in 3 h according to the wind speed and direction. So there is a high risk of transmission of COVID-19 through aerosols if their concentration is high and viruses have plenty of bases to stick it. Therefore our study suggests that there must be strict lockdown for all factors affecting the concentration of aerosols; otherwise, it may be an invitation to a disaster to give relaxes in lockdown in India like country with high aerosols in summer months.

3.5. Implications for preventing future transmission of 2019-nCoV

Before in March 2020, many studies speculated that the places with higher temperatures are in less risk, and it appeared that temperature might play an essential role in the spread of the virus. However, more new cases were recorded in regions with a temperature between 16 and 18 °C in March even more up to 30 °C in India during March and April 2020, which is now challenging the hypothesis that the rise in temperature will reduce the spread of Corona. The observation of more than 25,000 cases on each day in India makes it clear that the effect of rising summer temperature, if any, would not be observed for India, as the mean temperature for most of the major cities in India was above 30 °C for April and May. Indeed, laboratory experiments performed between 21 and 23 °C at a relative humidity of 40%, showed that the virus survived for several days on plastics and metals (van Doremalen et al., 2020). Therefore temperature may affect similar to the relationship observed between SARS-CoV and temperature (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020). Still, we can't say at what temperature and to what extent it would help in reducing the spread of 2019-nCoV. Under any circumstances, we believe that large gatherings (both indoor and outdoor) should be avoided across India.

Based on currently available data, 2019-nCoV is spreading quickly in regions with absolute humidity <10 g/m3 (Bukhari and Jameel, 2020), this has severe implications for the assumption that the 2019-nCoV spread would slow down during summer in the current hotspot of India as in many regions the absolute humidity might be above 10 g/m3 (Fig. 4). We have seen that summer and monsoon have no effects on the spread of COVID-19 cases in India; only government mitigation policies are going to reduce the COVID-19 spread over India.

4. Conclusions

The novel coronavirus pneumonia is caused by 2019-nCoV, which is a new pathogen for the human being. Due to its outbreak during the spring and summer, it is spreading very fast in a short period. Faced with this new disease, we lack reliable epidemiological information for effective treatment and prevention. However, any infectious disease origins and spread occur only when affected by certain natural and social factors through acting on the source of infection, the mode of transmission, and the susceptibility of the population. The weather and meteorological factors also may play a part in the coronavirus outbreak besides the social factors. Also, aerosols may play a crucial role during the spread of COVID-19. Following conclusions and suggestion may be drawn from the current study;

-

1.

We have studied the effect of environmental factors and aerosols on the spread of COVID-19 during March, April and May in India. We have studies the total number of daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 and its association with the temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity over India for March, April and May 2020. We found a positive association between daily new cases of COVID-19 with temperature for India. Relative humidity and Absolute humidity is showing negative association with daily cases of COVID-19 till mid-April in India and after that positive.

-

2.

To reducing the COVID-19 effect, summer-monsoon is not going to help majorly, as high absolute humidity regions like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu are getting the maximum number of confirmed daily COVID-19 cases (Fig. 1). So only the government's strict mitigation strategies would be helpful, whether their total lockdown or strictly imposing the social distancing for the community. Two coastal states of India (Kerala and Maharashtra) are the example for rest of the India who has an almost same meteorological environment and had same numbers of COVID-19 patient on 29th March, but during first lockdown period, their governments' strategies made a big difference as now Kerala is on 18th position, and Maharashtra is at the top in the total number of COVID-19 patient in India.

-

3.

There was a hope that increasing temperature in summer months in India may reduce the number of new COVID-19 cases, but it was not observed, also in India during summer, crop residue burning and major dust storms occurs (Kumar et al., 2015), which further degraded the air quality especially in the north Indian region and created the health emergency by producing respiratory diesis due to increased particulate matter, ultimately this enhanced the number of death of patients suffering from the COVID-19, also increased the chance of spreading through aerosols.

-

4.

We also investigated the aerosols and pollutants behavior with the total number of cases during the COVID-19 outbreak. The concentration in aerosols (AOD) and other pollutants (NO2) was sharply reduced during the first lockdown period (25 March-15 April) in India, which may have a negative effect and lowered the risk of COVID-19 to be airborne because less available aerosols as the base for the virus to stick on it. During second to fourth stage of lockdown the relaxation in lockdown increases the AOD and also the chance of spread of COVID −19. During the lockdown period, aerosols (AOD) and other pollutants (NO2; an indicator of PM2.5) reduced sharply with a maximum percentage drop of about 60 and 45, respectively. During lockdown period the reduction in surface air quality was also observed for six mega cities of India.

-

5.

Since many earlier studies and our findings are suggesting that COVID-19 may be airborne (WHO now confirms it for closed environment), so to slow down its spread, governments should impose strict lockdown and motivate the society to follow the social distancing, thermal scanning, and wearing a face mask when going outside. Health workers and those are working at the front line must take precautions as it may be airborne. Also, the mild infected and the severely infected patient should be kept in a separate medical facility.

-

6.

The structures of social contact critically determine the spread of the infection and, in the absence of vaccines, the control of these structures through large-scale social distancing measures appears to be the most effective means of mitigation. As in the previous study by Singh and Adhikari (2020) suggested that the three-week lockdown will be insufficient, and it's found true for India, our suggestion is for complete lockdown with minimal relaxation with strict social distancing.

-

7.

We found that early lockdown in India reduces the possible number of infections/death due to the coronavirus. In India, most of the cases identified during the lockdown period, which shows less effect of weather to slow it down, as it is already summer-monsoon in the Indian region. The number of cases per million populations was least for India in comparison to the USA and Europe, which showed that the government mitigations was working well as it was a historic move by the Indian government to lockdown 1.38 billion people with the different social and economic background when there were only 600 cases of the corona. But the relaxation in lockdown in later stage allowed the spread of COVID-19 rapidly in India as migrant workers started to move their home after first lockdown.

-

8.

The hypothesis that high Temp and high humidity will reduce the number of cases due to the coronavirus is not found working for the Indian region. So, there is again a need for the strict lockdown by the government over India and community should strictly follow the social distancing to reduce the number of COVID-19 cases. Relaxing in the lockdown and environmental rules in terms of pollutant emissions from power plants, factories, and other facilities would be the wrong choice. It could increase pollutants like PM2.5, which may result in more COVID-19 incidences and deaths in India. There is a need for a more appropriate study of the rate of outdoor transmission versus indoor and direct versus indirect transmission as they are not well understood, and environmental-related impacts are mostly applicable to outdoor transmissions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sarvan Kumar: Writing - original draft, Software, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to GIOVANNI NASA for providing the satellite data for AOD, NO2, Temperature, and Relative humidity and CPCB India for ground data for PM. We are thankful to the volunteers of COVID-19 Tracker/India (https://www.covid19india.org/) for providing all the data of India related to COVID-19. We thank NOAA for providing the HYSPLIT trajectories through their online models. The author is profoundly grateful to the Vice-Chancellor of V.B.S. Purvanchal University Prof. (Dr.) Raja Ram Yadav for encouraging the author to initiate this research. Author is also thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

References

- Barreca A.I., Shimshack J.P. Absolute humidity, temperature, and influenza mortality: 30 years of county-level evidence from the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;176 doi: 10.1093/aje/kws259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton D. The computation of equivalent potential temperature. Mon. Weather Rev. 1980;108:1046–1053. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bu J., Peng D.-D., Xiao H., Yue Q., Han Y., Lin Y., Hu G., Chen J. 2020. Analysis of Meteorological Conditions and Prediction of Epidemic Trend of 2019-nCoV Infection in 2020. medRxiv 2020.02.13.20022715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari Q., Jameel Y. Will coronavirus pandemic diminish by summer? SSRN Electron. J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3556998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- COVID/Tracker https://www.covid19india.org/ URL.

- van Doremalen N., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Kumar S., Kaskaoutis D.G., Singh R.P., Singh R.K., Mishra A.K., Srivastava M.K., Singh A.K. Meteorological, atmospheric and climatic perturbations during major dust storms over Indo-Gangetic Basin. Aeolian Res. 2015;17:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aeolia.2015.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Majumder M.S., Liu D., Poirier C., Mandl K.D., Lipsitch M., Santillana M. 2020. The Role of Absolute Humidity on Transmission Rates of the COVID-19 Outbreak. medRxiv 2020.02.12.20022467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarpia J.L., Rivera D.N., Herrera V., Morwitzer M.J., Creager H., Santarpia G.W., Crown K.K., Brett-Major D., Schnaubelt E., Broadhurst M.J., Lawler J.V., Reid S.P., Lowe J.J. 2020. Transmission Potential of SARS-CoV-2 in Viral Shedding Observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. medRxiv 2020.03.23.20039446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Adhikari R. 2020. Age-Structured Impact of Social Distancing on the COVID-19 Epidemic in India 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Du G. COVID-19 may transmit through aerosol. Irish J. Med. Sci. (1971-) 2020:5–6. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Tang K., Feng K., Lv W. High temperature and high humidity reduce the transmission of COVID-19. SSRN Electron. J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3551767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.R., Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- Worldometer https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ URL.