Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is a pandemic, resulting in large number of deaths all over the world. Lack of effective antiviral agents and vaccines pose a major challenge to control this pandemic.

Methods

Review the role of reverse quarantine in the control of COVID-19.

Results

Public health measures like social distancing, wearing face mask and hand hygiene along with quarantine measures form important steps to control the disease. Reverses quarantine is a useful strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Conclusions

Reverse quarantine is a promising public health measure to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Keywords: Quarantine, Reverse quarantine, COVID-19

Highlights

-

•

Quarantine and Reverse quarantine are common preventive measures in COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Separating those who are exposed to an infectious disease is called quarantine.

-

•

Separating those who are likely to develop severe illness from the public is Reverse quarantine.

-

•

It is a promising strategy to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Quarantine and Reverse quarantine are commonly used terms in connection with pandemic COVID-19.

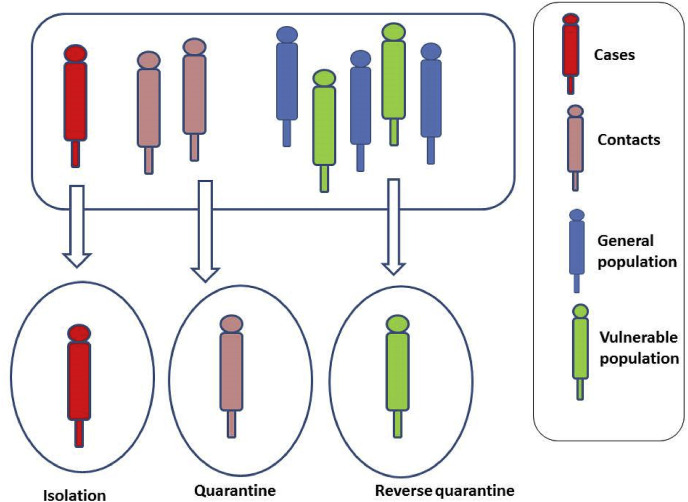

In simple terms, quarantine means a period of time during which a person who might have a disease is kept away from other people in order to prevent the spread of the illness. Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary defines quarantine as “restriction of freedom of movement of apparently well individuals who have been exposed to infectious disease, imposed for the usual maximal incubation period of the illness”. Separating those who are exposed to an infectious disease in order to stop the spread of infection is called quarantine, whereas separating those with the disease is called isolation [1](see Fig. 1 ). Quarantine practice started long ago from 14 century, when ships coming from plague infected areas were not allowed to dock, and were made to wait for 40 days in order to prevent the spread of the disease. The word quarantine comes from the Italian words “quaranta giorni” which means 40 days [2,3].

Fig. 1.

Isolation, quarantine and reverse quarantine.

The common diseases for which quarantine is implemented include cholera, diphtheria, infectious tuberculosis, plague, smallpox, yellow fever, viral hemorrhagic fevers (such as Marburg, Ebola, and Congo-Crimean), and severe acute respiratory syndromes in addition to COVID-19.

Quarantine is found to reduce the risk of COVID-19 disease by 44–81% and mortality by 31–63% [4]. Proper timing and duration of quarantine and the ability of the people and health care providers to adhere to the quarantine procedures determine the success rate of quarantine.

During this COVID-19 pandemic, it has been observed that older people, individuals with diabetes, hypertension, lung disease, kidney disease and immuno-compromised individuals are at risk of severe illness and considerably greater mortality with SARS-CoV-2 infection [5]. Reverse quarantine involves separating those who are likely to develop severe illness (vulnerable population), from the general public who are at the risk of the disease during an outbreak of an infectious disease, so that the associated mortality and morbidity could be reduced (Table 1 ) [6]. Vulnerable individuals should not be allowed to attend public gatherings and wherever possible, should be separated even from their family members, who have high risk of exposure (Table 2 ). Younger adults in the household, who have substantial contact with sick people on a regular basis as part of their profession, might consider living in a separate dwelling until the risk is lowered.

Table 1.

Reverse quarantine: who need it?

| Reverse quarantine: who need it? |

|---|

| Elderly |

| Pregnant ladies |

| Obesity |

| Infants and small children |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Hypertension |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Lung disease |

| Cardio-vascular disease |

| Malignancy |

| Immuno-compromised individuals |

| Post-transplant individuals |

| Individuals on immunosuppressive agents |

Table 2.

Comparison between Quarantine and Reverse quarantine.

| Features | Quarantine | Reverse quarantine |

|---|---|---|

| Separating | Those who are at risk of development of disease, because of contact with an infected individual | Those who are at risk of developing severe illness if infected |

| Duration | Maximal incubation period of the illness | Till the diseases is under control in that geographical area |

| People | Any individual who is at the risk of development of illness | Elderly or people with co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, renal disease |

| Purpose | To stop the transmission in the general population from potentially infective individual | Not much role in the prevention of transmission in the general population. To prevent infection in those who are at risk of developing critical illness |

| Place | Home or institutional | Most of the time home |

| Economic impact | Affect the financial status of the family, if he is the earning member of the family. | Elderly and those with other illness, may not be the earning member of the family. During RQ, society functions as usual, so that not much economic issues compared to lock down and quarantine. |

| Psychological issues | Results in psychological issues | Can lead to psychological issues, but may be less |

| Requirement | Early detection of cases and contact tracing are important to implement effective quarantine measures | Presence of the diseases under consideration in that geographical area is the pre requisite for RQ |

| Benefits | Helps to reduce disease burden Controlling the pandemic by reducing the risk of transmission |

Younger/healthy individuals will get mild infection and develop herd immunity, while older people get the benefit of it Altering the pandemic into a less harmful disease by reducing the chance of development of severe illness/critical illness |

| Net results | Reduces the number of cases in the society | Reduces the number of severe cases, requiring hospitalisation. Reduces the morbidity and mortality in the society |

Prolonged “lockdown” is not a feasible long-term solution due to its adverse economic implications. In COVID-19, there are large numbers of asymptomatic individuals and pre symptomatic individuals who can transmit the disease. Also pertinent here is the relative shortage of hospital facilities that cannot cope with a large influx of patients at a time; denial of care being inevitable in such an eventuality. Hence in the absence of effective treatment or vaccine, reverse quarantine is a promising and inexpensive solution.

The secondary attack rate (the percentage of close contacts that acquire the infection from a contact) of the SARS-CoV-2 virus ranges from 10.5 to 83, in various studies from multiple countries. The wide range is due to variation in living conditions and behaviour of the people involved. Experience from the diamond princess cruise ship has shown that the R-0 (ability of an infected person to infect other people) can be reduced from 7 to <1 by adhering to quarantine measures even in relatively small living spaces [7]. It follows that implementation of such measures can protect the vulnerable segment of the population to a significant degree.

However, implementing reverse quarantine in a populous country like India with a large number multigenerational family is a challenge. A substantial part of the population lives in cramped living conditions where social distancing is not feasible. Younger adults might not have the financial reserve to afford a second dwelling. If a vulnerable individual is the only earning member of the family, reverse quarantine is not a practical option.

To conclude, although there are limitations, reverse quarantine is promising strategy to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

References

- 1.CDC Quarantine and isolation. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/index.html Available at: Accessed 22 June 2020.

- 2.CDC History of quarantine. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/historyquarantine.html Available at: Accessed 22 June 2020.

- 3.Shedev P. The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(9):1071–1072. doi: 10.1086/344062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussbaumer-Streit B., Mayr V., AIulia Dobrescu, Chapman A., Persad E., Klerings I., Wagner G., Siebert U., Christof C., Zachariah C., Gartlehner G. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013574. CD013574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh A.K., Gillies C.L., Singh R., Singh A., Chudasama Y., Coles B., Seidu S., Zaccardi F., Davies M.J., Khunti K. Prevalence of comorbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID -19: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metabol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dom.14124. Accepted Author Manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulia K.K., Kumar V.M. Reverse quarantine: management of COVID-19 by Kerala with its higher number of aged population [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 4] Psychogeriatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1111/psyg.12582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizumoto K., Chowell G. Infectious Disease Modelling; 2020. Transmission potential of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) onboard the diamond princess cruises ship. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]