Abstract

Background:

Trapping of apoB lipoprotein particles within the arterial wall initiates and drives the atherosclerotic process from beginning to end. Very low-density lipoprotein particles (VLDL) contain most of the triglyceride in plasma whereas low-density lipoprotein particles (LDL) particles contain most of the cholesterol. Smaller numbers of chylomicron and Lp(a) particles are also present in plasma. All these particles have one molecule of apoB. Therefore, plasma apoB equals the total number of apoB particles. Because the lipid content of apoB particles is variable, plasma triglyceride and cholesterol are not always accurate-measures of the number of apoB particles.

The Cholesterol Model of Atherosclerosis

The conventional model of atherosclerosis presumes that the mass of cholesterol within VLDL and LDL particles is the principal determinant of the mass of cholesterol that will be deposited within the arterial wall and will drive atherogenesis. But cholesterol can only enter the arterial wall within apoB particles and the mass of cholesterol that will be deposited is determined by the rate at which apoB particles are trapped within the arterial wall rather than passing harmless through.

The ApoB Particle Model of Atherogenesis

The number of apoB particles that enter and are trapped within the arterial wall is determined primarily by the number of apoB particles within the arterial lumen. However, once within the arterial wall, smaller cholesterol-depleted apoB particles have a greater tendency to be trapped than larger cholesterol-enriched apoB particles because they bind more avidly to the glycosaminoglycans within the subintimal space of the arterial wall. If so, a cholesterol-enriched particle would deposit more cholesterol than a cholesterol-depleted apoB particle. By contrast, more smaller apoB particles that enter the arterial wall will be trapped than larger apoB particles. The net result is, with the exceptions of the abnormal chylomicron remnants in type III hyperlipoproteinemia and Lp(a), all apoB particles are equally atherogenic.

ApoB, therefore, unifies, amplifies, and simplifies the information from the conventional lipid markers as to the atherogenic risk attributable to the apoB lipoproteins.

Introduction

Trapping of apoB lipoprotein particles within the arterial wall is the fundamental step that initiates and drives the atherosclerotic process from beginning to end, from the first appearance of fatty streaks to the ultimate development of the complex lesions that are vulnerable to the acute transformations, such as plaque rupture and endothelial erosion, that are the immediate precursors of clinical events. 1 The concentration of apoB particles within the arterial lumen is the primary determinant of the number of apoB particles that will be trapped within the arterial wall. But the proportion of apoB particles that are trapped within the arterial wall versus the proportion that pass harmlessly through is also influenced by the size of the apoB particles and by the structure of the glycosaminoglycans within the subintimal space of the arterial wall. Trapping of apoB particles deposits atherogenic cholesterol within the arterial wall. However, because the cholesterol content and therefore, the size of apoB particles, varies significantly 2 and because other components of apoB particles, such as phospholipids and apoB itself, if oxidized, are strong proatherogenic factors, 3-5neither LDL-C nor non-HDL-C are as accurate as apoB as markers of cardiovascular risk. Moreover, recent data indicate that the risk from a VLDL particle approximates closely the risk from an LDL particle. 6 Accordingly, apoB sums the atherogenic risk due to the TG-rich VLDL apoB particles and the cholesterol-rich LDL apoB particles and, in conjunction with the plasma lipids, could improve the clinical assessment and management of the atherogenic dyslipoproteinemias. 7

Plasma apoB

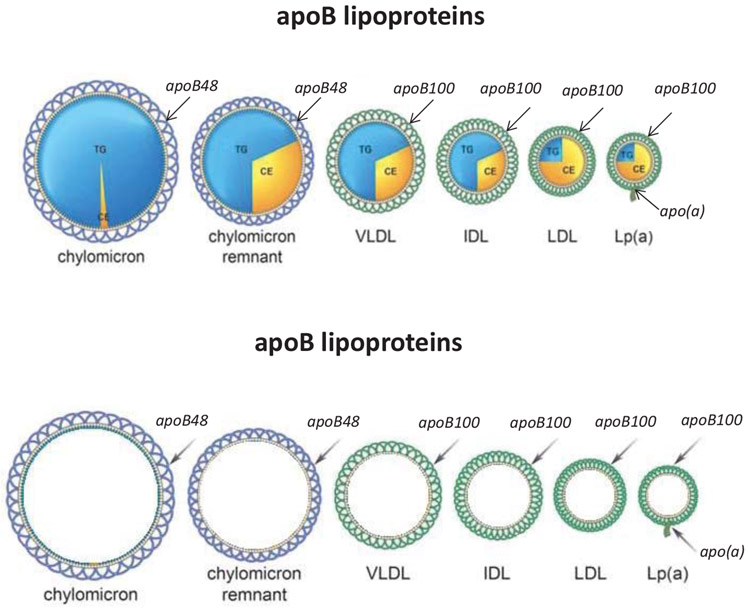

ApoB-containing lipoproteins are spherical particles (Figure 1). Each has a monolayer of phospholipids arranged around its circumference within which are small amounts of cholesterol and through which a single molecule of apoB48 or apoB100 encircles the lipoprotein particle. 8 The apoB molecule provides structural stability and stays with the particle throughout its metabolic lifetime whereas variable amounts of TG and cholesterol ester (CE) constitute the core of the particle. 2 (Figure 1) The plasma concentrations of TG, non-HDL-C and LDL-C are the sums of these lipids within the apoB particles. Multiple other apolipoproteins, such as the apoC apolipoproteins and apoE, are present on the surface of chylomicrons and VLDL particles. These play important metabolic roles, particularly in modulating the rate at the TG-rich lipoproteins are cleared from plasma, but are not the focus of this review. 7

Figure 1.

illustrates schematically the apoB48 and apoB100 lipoprotein particles.

1 apoB molecule = 1 lipid particle. Therefore, apoB plasma concentration = total number of atherogenic lipid particles

ApoB assays recognize both apoB48 and apoB100. Because there is a single molecule of either apoB48 or apoB100 per particle, 8 plasma apoB equals the total number of apoB48, apoB100 particles and Lp(a) particles (Figure 1). However, because there are so few apoB48 particles at any time, even in postprandial samples, total apoB is simply the sum of VLDL, LDL and Lp(a) particles. Thus, fasting is not necessary to measure apoB.

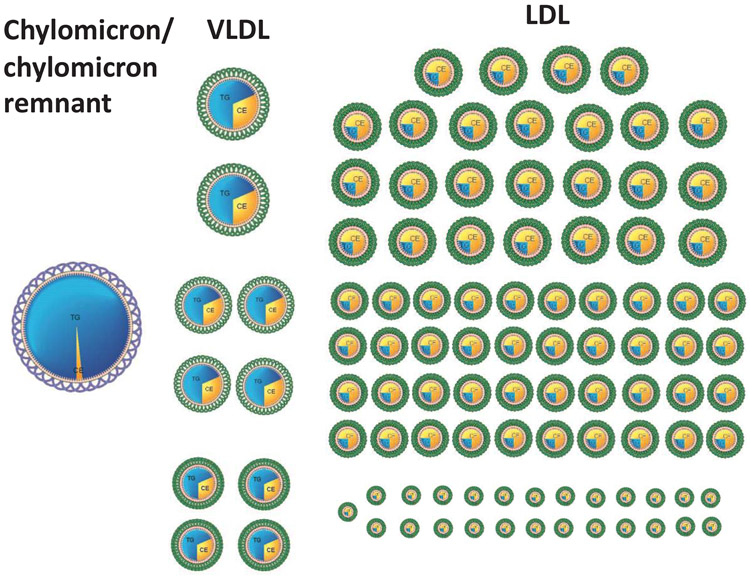

Figure 2 demonstrates the great differences in the relative numbers of the different apoB particles. 2 In subjects with normal TG (TG < 1.5 mmol/L), for every chylomicron and/or chylomicron remnant particle, there are approximately 10 VLDL particles. This is why, in general, VLDL particles are more important determinants of atherogenic risk than chylomicron remnant particles. Similarly, because VLDL particles have a short half-life in plasma whereas LDL particles have a longer half-life, there are many more LDL particles than VLDL particles in plasma. 2 Thus, in patients with normal TG levels, for every VLDL particle, there are approximately 9 LDL particles. 2 (Figure 2) As plasma TG levels increase, the proportion of VLDL particles increases, but this relation is not exact and, with the exception of the uncommon disorder, type III hyperlipoproteinemia, there are always many more LDL particles than VLDL particles. 2

Figure 2.

illustrates the relative numbers of apoB particles in plasma in the postprandial period.

Metabolic Bases for variability in the composition of VLDL and LDL particles.

The superiority of apoB over cholesterol and TG as a marker of cardiovascular risk is based on the variability in the lipid composition of the apoB lipoproteins. Much is known about the pathophysiological bases for the differences in cholesterol content in apoB particles. 9-11 VLDL particles are grossly heterogeneous in composition and size. The liver may secrete larger triglyceride-enriched VLDL particles, VLDL1 particles, or smaller VLDL2 particles, which contain less TG. 12 Moreover, the mass of TG within VLDL particles diminishes as the TG is hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase. Although TG is the dominant core lipid, VLDL particles also contain substantial amounts of CE. LDL particles can differ in the mass of CE within their core and, consequently, can differ in size. 8 But, as will be demonstrated beneath, all have the same atherogenic potential.

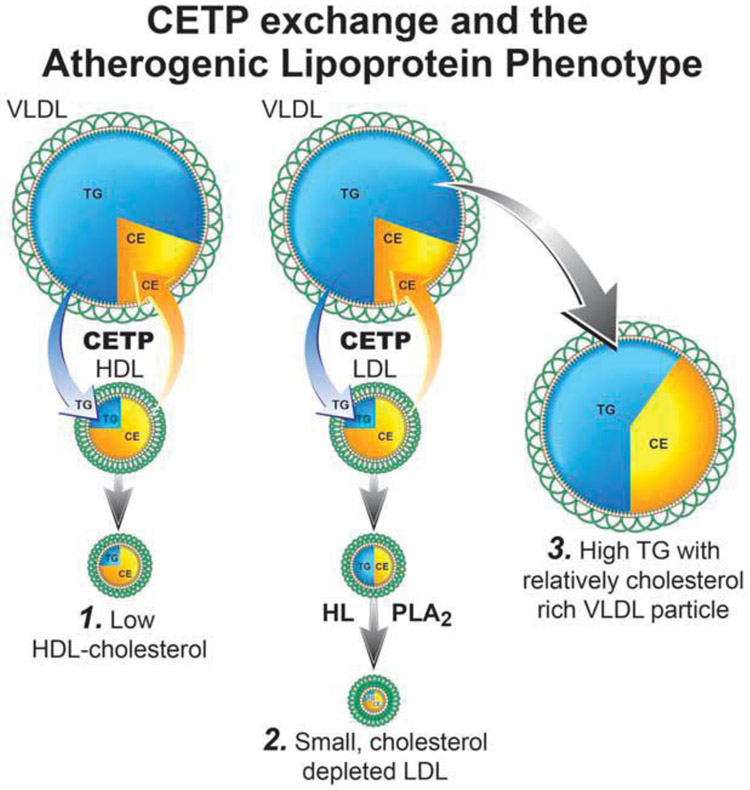

Variance in the composition of the apoB particles is based on CETP-mediated exchange of the core lipids- CE and TG- amongst the plasma lipoproteins. 12,13 (Figure 3) If a TG from VLDL is exchanged for a CE molecule from LDL, the VLDL particle becomes relatively enriched with CE; the TG content of the LDL particle increases, but its CE content decreases. Subsequent hydrolysis of the TG within the LDL particle, probably by hepatic lipase, produces smaller, cholesterol-depleted particles. 9 Once plasma TG are greater than 1.5 mmol/L, LDL particles, on average, contain less cholesterol than usual, are smaller than usual, and LDL-C will underestimate the number of LDL particles 14 The same sequence produces a low HDL-C in patients with hypertriglyceridemia explaining why this triad of lipid abnormalities-hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-C, and small cholesterol depleted LDL particles- the so-called atherogenic triad- 15 are so often so entwined and therefore why their relative pathophysiological significance is so difficult to disentangle.

Figure 3.

illustrates the metabolic steps by which HDL-C is lowered based on exchange of CE and triglycerides as well as the steps by which smaller cholesterol—depleted LDL particles are generated.

Importantly, LDL particles can also be cholesterol-enriched. However, the metabolic processes that lead to larger cholesterol-enriched particles are less well-understood than the processes that lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted particles. In individuals with cholesterol-enriched apoB particles, TG are characteristically normal or even low, HDL-C normal or high, and apoB normal or high. 16-20

Epidemiological basis for the role of apoB as a marker of the concentration of proatherogenic lipoproteins in plasma

Modern epidemiological tools enable analyses that lead to conclusions consistent with the pathophysiological arguments outlined above. The original studies that suggested apoB to be a more accurate marker of cardiovascular risk than TC or LDL-C were simple cross-sectional analyses.21,22 Subsequently, prospective observational studies23 confirmed these initial findings. However, while the majority of studies favoured apoB over LDL-C, not all concluded that apoB was superior to non-HDL-C with some, such as the Emerging Risk Factor Study 24 and the Copenhagen Heart Study 25 reporting non-HDL-C and apoB were equivalent predictors. Great emphasis was placed on the c-statistic to demonstrate whether a new marker significantly improved the prediction of risk. Unfortunately, while the c-statistic does evaluate the overall performance of a risk model, it is not a reliable tool to judge which marker is responsible for risk. 26 Thus lay the balance of evidence until two new epidemiological analytical approaches-discordance analysis and Mendelian randomization- were employed to deal with the challenge of discriminating amongst highly correlated markers such as LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apoB.

Correlation, Concordance, and Discordance Analysis

Correlation expresses the overall relation between the changes in two variables. Neither the number of VLDL particles (VLDL apoB) nor the total apoB correlate well with plasma TG. 2 Accordingly, VLDL particle number cannot be reliably inferred from plasma TG. By contrast, because the variance in cholesterol mass per particle is less, LDL-C and apoB are highly correlated while non-HDL-C and apoB are even more highly correlated. These high correlations have been used to argue that LDL-C, and even more so, non-HDL-C, are clinically equivalent to apoB and therefore acceptable surrogates for apoB. 27

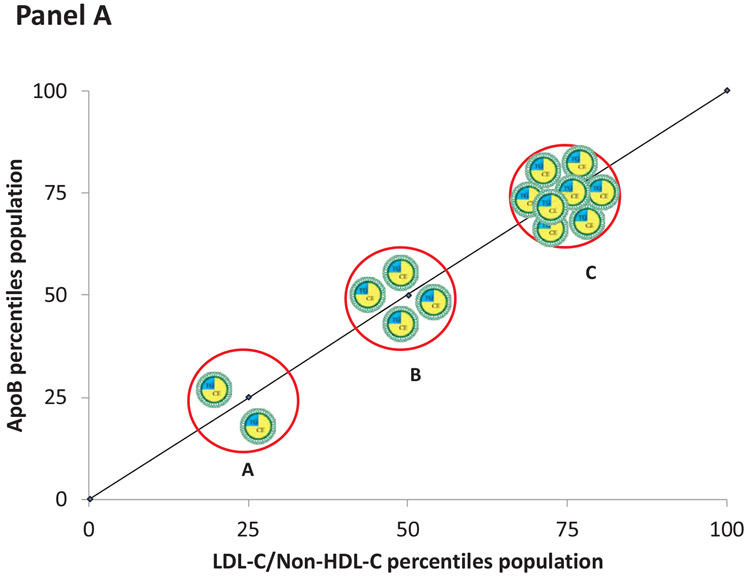

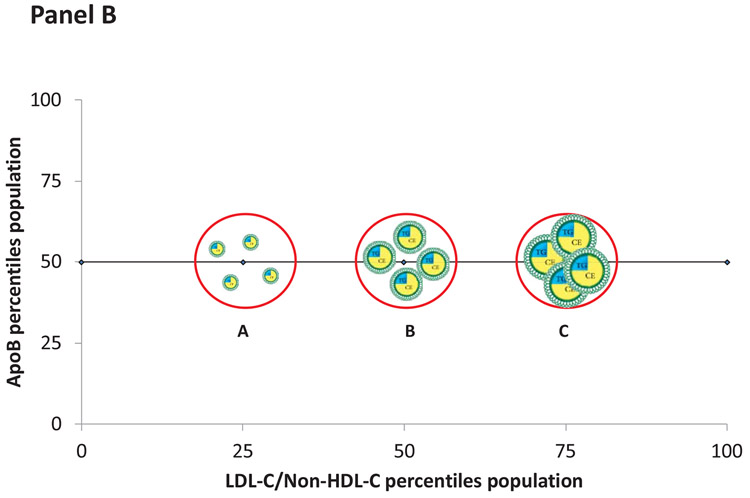

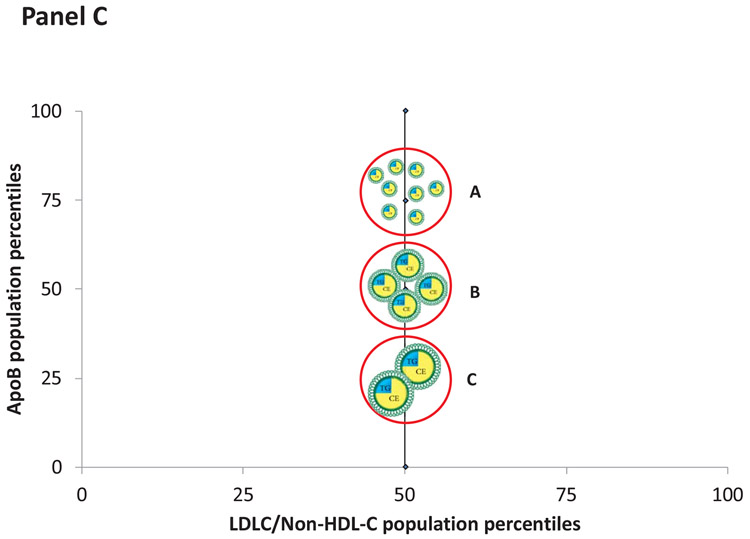

However, correlation at a population level does not establish clinical equivalence at an individual level. Figure 4, Panel A illustrates that as the number of apoB particles containing an average mass of cholesterol increases, the concentration of LDL-C/non-HDL-C and the concentration of apoB increase proportionately. The changes in LDL-C/non-HDL-C and apoB, in this instance, are concordant. However, panel B illustrates that for a given value of apoB (the 50th percentile), the levels of LDL-C/non-HDL-C may range from the 25th the 75th percentile. In these examples, the values of LDL-C/non-HDL-C and apoB are discordant and will predict risk differently. Panel C illustrates discordance when LDL-C/non-HDL-C are fixed but apoB varies. The accuracies of these differences in predictions can be tested in epidemiological studies.

Figure 4.

Panel A illustrates discordance in LDL-C and apoB when the apoB particles contain an average mass of cholesterol. Panel B illustrates discordance when apoB particles are cholesterol-enriched whereas Panel C illustrates discordance when apoB particles are cholesterol-depleted.

Discordance analysis is constructed so that the markers, which are being compared, make diametrically different predictions: in the discordant groups with high LDL-Cor high non-HDL-C but low apoB, cholesterol predicts high risk, apoB low risk whereas in the groups with low-LDL-C or non-HDL-C but high apoB, the reverse is the case. 28 One marker will be right, the other wrong. Multiple discordance analyses of major prospective observational studies have been published with either apoB or LDL, particle number compared to LDL-C and/or non-HDL-C 16,18-20,29-33.

Multiple methods have been used to create the discordant groups, ranging from division at the median of the markers to separation based on residuals. These different definitions have resulted in discordant groups that range from about 20% to about 60% of the total population. In all instances, the markers of particle number, apoB or LDL particle number- were stronger predictors of cardiovascular risk than LDL-C. In five major studies 16,18-20,32 apoB was shown to be a more accurate marker of risk than non-HDL-C. In the Women’s Health Study and the UK Biobank study, a conventional analysis did not demonstrate that apoB was a more accurate marker of cardiovascular risk than non-HDL-C 31,32 whereas this was demonstrated by discordance analysis.20,32 Moreover, a discordance analysis based on Mendelian randomization, which compared the benefit of lowering LDL-C versus the benefit of lowering apoB, confirmed these findings.33 The results of discordance analysis are clear and consistent: apoB is a more accurate marker of cardiovascular risk attributable to the apoB lipoprotein particles than LDL-C and non-HDL-C and the size of the discordant groups is sufficiently large to make the phenomenon clinically relevant.

Evidence from Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) and Mendelian Randomization

RCTs have demonstrated that statins, statins plus ezetimibe, and statins plus PCSK9 inhibitors significantly lower cardiovascular risk.34 All increase LDL receptor activity at the surface of hepatocytes, thereby increasing the rate at which apoB particles, primarily LDL apoB particles, are removed from plasma. Statins do so by reducing hepatic and intestinal cholesterol synthesis, ezetimibe by reducing cholesterol absorption and delivery to the liver, and PCSK9 inhibitors by reducing the degradation of LDL receptors within the hepatocyte. 34 All lower LDL-C and non-HDL-C because all lower apoB particle number in plasma.

Statins lower LDL-C more than non-HDL-C more than apoB 35 because larger cholesterol-rich LDL apoB particles interact more avidly with the LDL receptor than smaller cholesterol-depleted ones. 36 Therefore, their concentration will decrease more than the concentration of smaller cholesterol-depleted apoB particles. Conventional epidemiological analyses have yielded mixed results as to whether LDL-C, non-HDL-C or apoB is the best marker of the effectiveness of therapy. A participant level meta-analysis of 8 major statin trials demonstrated that non-HDL-C was a marginally more accurate marker of residual risk than apoB or LDL-C. 37 A Bayesian analysis of clinical trials using multiple therapeutic agents did not demonstrate apoB to be a superior marker of benefit. 38 By contrast, a meta-analysis of 7 major statin trials, using both frequentist and Bayesian approaches, demonstrated that benefit was more closely related to the decrease in apoB than to the decreases in LDL-C and non-HDL-C. 39

Mendelian randomization has added to the evidence that the number of apoB particles within the arterial lumen is the most direct measure of the atherogenic injury that the apoB particles will inflict over time on the arterial wall. CETP inhibitors (CETPI) were developed to test the hypothesis that raising HDL-C would reduce cardiovascular events. However, trials of statin-CETP inhibitor combination therapy, which demonstrated large decreases in LDL-C, did not produce significant clinical benefit, 40 a result, which is inconsistent with a causal role for LDL-C in ASCVD.34,38

To resolve the dilemma, Ference et al 33 combined variants in the CETP and HMGCR genes to create genetic scores that mimic the effects of CETP inhibitors and statins. A CETP score at or above the median was associated with higher levels of HDL-C, lower levels of LDL-C and apoB, and lower levels of cardiovascular risk. An HMGCR score at or above the median was not associated with significant changes in HDL-C but was associated with lower levels of LDL-C, apoB and cardiovascular risk. For participants with both scores above the median, which is analogous to combination therapy with a CETP inhibitor and a statin, the reduction in LDL-C was additive, but the reduction in apoB was attenuated. The attenuated reduction in apoB was associated with a non-significant decrease in cardiovascular risk, thus explaining the otherwise paradoxical finding of a significant decrease in LDL-C with combination statin-CETP inhibitor therapy without clinical benefit. Only in the REVEAL trial was the decrease in apoB large enough to produce significant clinical benefit. 41 Thus, Mendelian randomization indicates that the primary mechanism of benefit from lowering LDL-C relates to the lowering of the number of LDL particles- that is, to the lowering of apoB. It follows that apoB is a more accurate index of the adequacy of LDL lowering therapy than LDL-C. Indeed, Martin et al demonstrated that in approximately one third of patients who achieved a level of LDL C <70mg/dl, apoB was substantially higher, pointing to the potential for further benefit from LDL lowering therapy. 42

Ference and his colleagues subsequently applied Mendelian randomization to examine whether lowering TG reduces cardiovascular risk. 6 Just as LDL-C has been accepted as the measure of LDL, so TG has been accepted as the measure of VLDL. Accordingly, Ference et al created a genetic score equivalent to a drug that would lower TG via increased LPL activity as well as the genetic score equivalent to a drug that would lower LDL-C via increased LDL receptor (LDLR) activity. 6 The LPL genetic score was associated with a large decrease in TG but a very small, non-significant, increase in LDL-C whereas the LDLR score was associated with a large decrease in LDL-C with only a very small decrease in TG. However, when these decreases in LDL-C and TG were normalized for the same decrease in apoB, the reduction in risk associated with the LPL genetic score and the reduction in risk associated with the LDLR score were very similar.

Taken together, these findings suggest that, except for the small minority too large to enter the arterial wall, the great majority of VLDL particles are as atherogenic as LDL particles. Since each VLDL and LDL particle has one molecule of apoB, plasma apoB represents the sum of the atherogenic risk attributable to VLDL plus LDL particles. Of interest, these findings are consistent with previous observational studies, which demonstrated the risk in patients with hypertriglyceridemia was determined by plasma apoB, not by plasma TG. 43-48 They also explain why fibrates, which produce moderate to marked reductions in plasma TG and VLDL apoB, failed to consistently produce clinical benefit. Fibrates failed because although, they produce large decreases in VLDL apoB, they produce only small decreases in LDL apoB, which make up most of the apoB particles in plasma. Consequently, in general, they produced only modest changes in total apoB. 2 However, in those hypertriglyceridemic patients in whom VLDL apoB rises to 25 to 30% of total apoB, the reduction in total apoB could reach clinical significance. This may explain the positive subgroup findings of benefit of fibrates in hyperTG patients with low HDL-C. 49 The inconsistent effects of fibrates on clinical benefit are, therefore, consistent with the model that benefit depends on reduction in apoB.

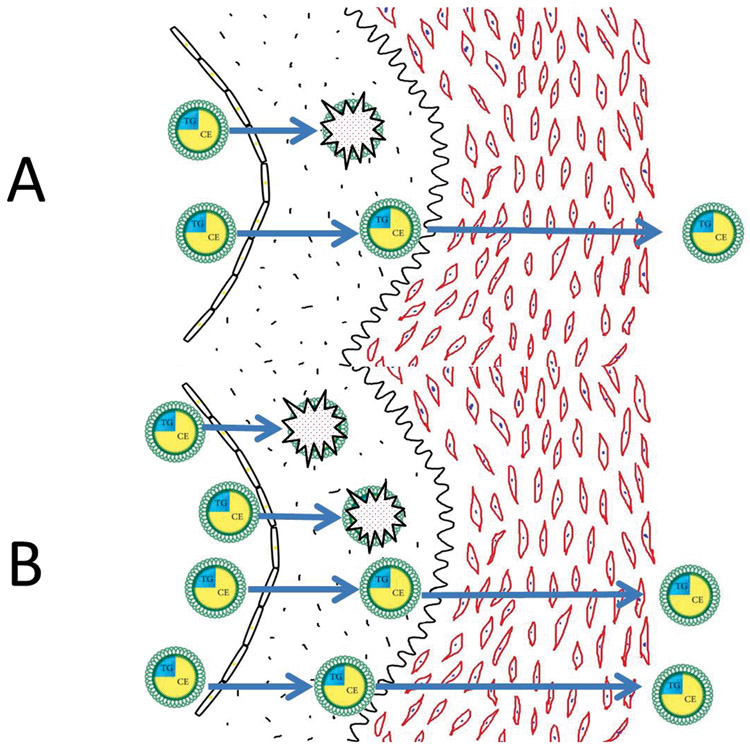

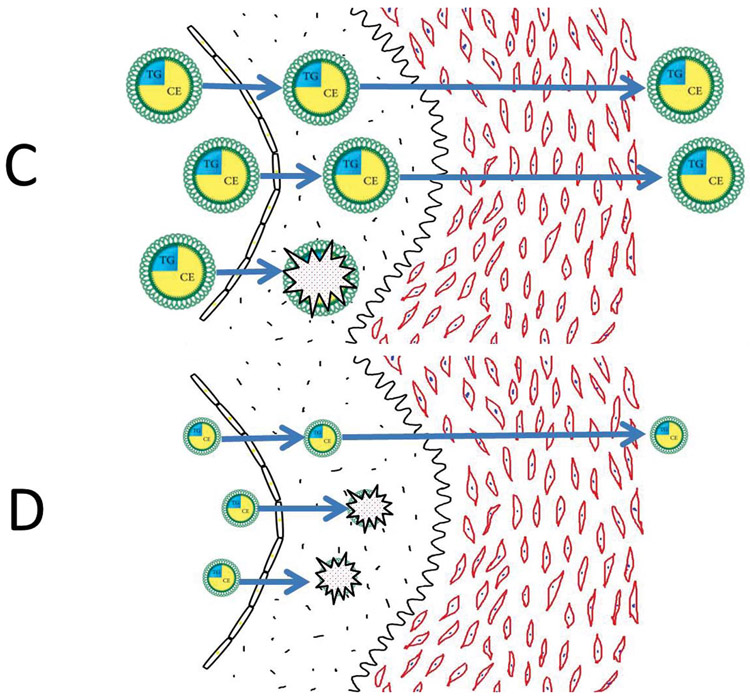

The apoB particle model of atherosclerosis

We now propose a model to explain why the atherogenic risk associated with the apoB lipoproteins relates more directly to their number than to the mass of cholesterol within them. Figure 5 demonstrates that the number of apoB particles in the lumen of an artery is the primary determinant of the rate at which apoB particles enter the arterial wall and are trapped within the subintimal space of the arterial wall. The more apoB particles within the lumen of the artery, the more that will enter the arterial wall, and, all things being equal, the more apoB particles that will be trapped within the arterial wall. However, all things are not always equal: as illustrated in Figure 5, smaller apoB particles containing less cholesterol enter the arterial wall more easily 50 and bind more avidly to the glycosaminoglycans within the arterial wall than larger apoB particles containing more cholesterol. 51,52 Thus, more, smaller, cholesterol-depleted particles will be trapped than will a similar number of larger, cholesterol-enriched particles that have entered an arterial wall. On the other hand, the more cholesterol within an apoB particle that has been trapped within the arterial wall, the more cholesterol that will be released at that site to injure the wall. There is, therefore, an equivalence between greater injury per particle from trapping of cholesterol-richer particles, but greater injury from trapping of more cholesterol-depleted particles. The net result is that all LDL particles pose, more or less, equal risk.

Figure 5.

Panel A illustrates the number of apoB particles within the lumen of an artery is the prime determinant of the number of apoB particles trapped within the arterial wall. ApoB particles trapped within the arterial wall initiate and sustain the inflammatory, destructive processes that ultimately produce advanced atherosclerosis within that segment of the arterial wall.

But the unification and, therefore, the simplification offered by apoB have gone further: Ference et al have shown that VLDL particles pose equal atherogenic risk to LDL particles. 6 Since the number of LDL particles is always many multiples of the number of VLDL particles, 2 the total risk from LDL particles is almost always much greater than the risk from VLDL particles, accounting for why cholesterol is much more closely linked to cardiovascular risk triglycerides to cardiovascular risk, notwithstanding that hypertriglyceridemia is more common in patients with cardiovascular disease than hypercholesterolemia. 53,54

There are two exceptions to the rule that all apoB particles are equally atherogenic. The first is type III hyperlipoproteinemia, which is characterized by markedly increased numbers of abnormally cholesterol-enriched apoB48 and apoB100 remnant particles.55,56The cholesterol content of these particle is so great as to make the damage per particle much greater than otherwise and these abnormal particles are present in 20 to 40-fold excess of concentrations of remnants in normals and hypertriglyceridemic patients, who do not have type III. 2 Type III cannot be diagnosed from the conventional lipid panel, which is a significant limitation of current practice, but can be accurately identified based on TC, TG and apoB.57

The second is Lp(a), given the strong evidence that elevated levels of Lp(a) independently add significantly to cardiovascular risk and are critically related to the pathophysiology of aortic stenosis.58,59 A large meta-analysis demonstrated that Lp(a) appears to confer increased risk for cardiovascular risk despite statin therapy 60 and subanalyses from PCSK9 inhibitor trials have demonstrated that even among individuals with near-optimal LDL-C levels, Lp(a) remains a source of residual risk.61Conversely, in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia, characterized by a high burden of apoB particles, the presence of high Lp(a) further increases risk. 62,63

In addition, variations in glycosaminoglycan structure and perhaps other elements of the arterial wall might influence the avidity of binding of apoB and therefore increase fractional trapping of apoB particles. 64 Thus, the hypothesis that glycation of apoB particles promotes binding of apoB particles deserves further attention. 65 Finally, there is likely significant interindividual variation in the intensity of the innate and acquired immune responses, ie B and T cell responses, to apoB particles trapped within the arterial wall and therefore significant variation in in the inflammatory-mediated destruction of the arterial wall. 68

Accordingly, variance in the sequence of events after an apoB particle enters the arterial wall will account for much of the individual variance of risk at the same apoB. Nevertheless, everything first depends on the entry of an apoB particle into the arterial wall, and this depends, most of all, on the concentration of apoB particles in the arterial lumen.

Summary

An apoB particle is the basic unit of injury to the arterial wall. The more apoB particles within the lumen of the artery, the greater the trapping of apoB particles within the arterial wall, the greater the injury to the arterial wall. The more apoB particles are reduced by therapy, the less the injury to the arterial wall, the greater the opportunity for healing. Moreover, nowadays apoB can be measured accurately and inexpensively.67-69 Thus, apoB integrates the information from the conventional lipid panel and, therefore, unifies, amplifies and simplifies our understanding of the role of the apoB lipoprotein particles in atherogenesis.

Acknowledgment

Role of Funder/Sponsor Statement

This research was supported by the Doggone Foundation, which played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures/Funding Support:

Dr. Sniderman has no conflict of interest.

Dr. Thanassoulis has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, Sanofi-Regeneron and Ionis and in speaker bureaus for Amgen and Sanofi; has received grant funding from Ionis and Servier, not related to this work.

Dr. Glavinovic has no conflict of interest.

Dr. Navar reported receiving grants and personal fees from Amarin, Amgen, Regeneron, and Sanofi; personal fees from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk; grants from Janssen; and salary support through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K01HL133416).

Dr. Pencina reports funding from Doggone Foundation/McGill University Health Centre related to this work and past funding from grants from Sanofi/Regeneron and Amgen, personal fees from Merck and Boehringer Ingelheim, not related to this work.

Dr. Catapano reported receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Aegerion, Genzyme, Sanofi, Merck & Co, Menarini, Kowa, and Pfizer and grants from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, Mediolanum, Sanofi, Merck & Co, Pfizer, Regeneron, Rottapharm, Recordati, and Sigma tau.

Dr. Ference reported receiving personal fees from Merck & Co, Amgen, Esperion Therapeutics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Pfizer, dalCOR, The Medicines Company, CiVi BioPharma, KrKA Pharmaceuticals, American College of Cardiology, European Society of Cardiology, and the European Atherosclerosis Society and grants from Merck & Co, Amgen, Novartis, and Esperion Therapeutics. Dr Ference is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre at the Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Tweet: #apoB clarifies and unifies -and therefore simplifies- the role of the atherogenic lipoproteins in causing CV disease.

Originality of Content

All the material including the Figures is original and has not been published elsewhere.

References:

- 1.Borén J, Williams KJ. The central role of arterial retention of cholesterol-rich apolipoprotein-B-containing lipoproteins in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a triumph of simplicity. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27(5):473–483. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sniderman AD, Couture P, Martin SS, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular risk: a cautionary note about metabolic confounding. J Lipid Res. 2018;59(7):1266–1275. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R082271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Que X, Hung M-Y, Yeang C, et al. Oxidized phospholipids are proinflammatory and proatherogenic in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Nature. 2018;558(7709):301–306. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0198-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ketelhuth DFJ, Rios FJO, Wang Y, et al. Identification of a danger-associated peptide from apolipoprotein B100 (ApoBDS-1) that triggers innate proatherogenic responses. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2433–43–1–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avraham-Davidi I, Ely Y, Pham VN, et al. ApoB-containing lipoproteins regulate angiogenesis by modulating expression of VEGF receptor 1. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):967–973. doi: 10.1038/nm.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ference BA, Kastelein JJP, Ray KK, et al. Association of Triglyceride-Lowering LPL Variants and LDL-C-Lowering LDLR Variants With Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 2019;321(4):364–373. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Graaf J, Couture P, Sniderman A. ApoB in Clinical Care. Houten: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elovson J, Chatterton JE, Bell GT, et al. Plasma very low density lipoproteins contain a single molecule of apolipoprotein B. The Journal of Lipid Research. 1988;29(11): 1461–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bemeis KK, Krauss RM. Metabolic origins and clinical significance of LDL heterogeneity. The Journal of Lipid Research. 2002;43(9): 1363–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman MJ, Laplaud PM, Luc G, et al. Further resolution of the low density lipoprotein spectrum in normal human plasma: physicochemical characteristics of discrete subspecies separated by density gradient ultracentrifugation. The Journal of Lipid Research. 1988;29(4):442–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng B, Thompson GR, Sniderman AD, Forte TM, Krauss RM, Kwiterovich PO. Composition and distribution of low density lipoprotein fractions in hyperapobetalipoproteinemia, normolipidemia, and familial hypercholesterolemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80(21):6662–6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adiels M, Packard C, Caslake MJ, et al. A new combined multicompartmental model for apolipoprotein B-100 and triglyceride metabolism in VLDL subfractions. The Journal of Lipid Research. 2005;46(l):58–67. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400108-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pattnaik NM, Montes A, Hughes LB, Zilversmit DB. Cholesteryl ester exchange protein in human plasma isolation and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;530(3):428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin BA, Caslake MJ, Yip B, Tait GW, Packard CJ, Shepherd J. Rapid isolation of low density lipoprotein (LDL) subfractions from plasma by density gradient ultracentrifugation. ATH. 1990;83(1):59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toth PP. Insulin resistance, small LDL particles, and risk for atherosclerotic disease. Curr Vase Pharmacol. 2014;12(4):653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sniderman AD, Islam S, Yusuf S, McQueen MJ. Discordance analysis of apolipoprotein B and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol as markers of cardiovascular risk in the INTERHEART study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225(2):444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mora S, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Discordance of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol with alternative LDL-related measures and future coronary events. Circulation. 2014; 129(5):553–561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Zdrojewski T, et al. Apolipoprotein B improves risk assessment of future coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study beyond LDL-C and non-HDL-C. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(10):2047487315569411–1327. doi: 10.1177/2047487315569411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkins JT, Li RC, Sniderman A, Chan C, Lloyd-Jones DM. Discordance Between Apolipoprotein B and LDL-Cholesterol in Young Adults Predicts Coronary Artery Calcification: The CARDIA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(2): 193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawler PR, Akinkuolie AO, Ridker PM, et al. Discordance between Circulating Atherogenic Cholesterol Mass and Lipoprotein Particle Concentration in Relation to Future Coronary Events in Women. Clin Chem. 2017;63(4):870–879. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.264515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avogaro P, Bon GB, Cazzolato G, Quinci GB. Are apolipoproteins better discriminators than lipids for atherosclerosis? The Lancet. 1979;1(8122):901–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sniderman A, Shapiro S, Marpole D, Skinner B, Teng B, Kwiterovich PO. Association of coronary atherosclerosis with hyperapobetalipoproteinemia [increased protein but normal cholesterol levels in human plasma low density (beta) lipoproteins]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(1):604–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sniderman AD, Robinson JG. ApoB in clinical care: Pro and Con. Atherosclerosis. 2019;282:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benn M, Nordestgaard BG, Jensen GB, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Improving prediction of ischemic cardiovascular disease in the general population using apolipoprotein B: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(3):661–670. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000255580.73689.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pencina MJ, Navar AM, Wojdyla D, et al. Quantifying Importance of Major Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation. 2019;139(13): 1603–1611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sniderman AD, St-Pierre AC, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Després J-P, Lamarche B. Concordance/discordance between plasma apolipoprotein B levels and the cholesterol indexes of atherosclerotic risk. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(10):1173–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cromwell WC, Otvos JD, Keyes MJ, et al. LDL Particle Number and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease in the Framingham Offspring Study - Implications for LDL Management. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2007;1(6):583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otvos JD, Mora S, Shalaurova I, Greenland P, Mackey RH, Goff DC. Clinical implications of discordance between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and particle number. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2011;5(2): 105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora S, Otvos JD, Rifai N, Rosenson RS, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein particle profiles by nuclear magnetic resonance compared with standard lipids and apolipoproteins in predicting incident cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation. 2009;119(7):931–939. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welsh C, Celis-Morales CA, Brown R, et al. Comparison of Conventional Lipoprotein Tests and Apolipoproteins in the Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease: Data from UK Biobank. Circulation. 2019;8:197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ference BA, Kastelein JJP, Ginsberg HN, et al. Association of Genetic Variants Related to CETP Inhibitors and Statins With Lipoprotein Levels and Cardiovascular Risk. JAMA. 2017;318(10):947–956. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(32):2459–2472. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sniderman AD. Differential response of cholesterol and particle measures of atherogenic lipoproteins to LDL-lowering therapy: implications for clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2008;2(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund-Katz S, Laplaud PM, Phillips MC, Chapman MJ. Apolipoprotein B-100 conformation and particle surface charge in human LDL subspecies: implication for LDL receptor interaction. Biochemistry. 1998;37(37):12867–12874. doi: 10.1021/bi980828m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, et al. Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307(12): 1302–1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson JG, Wang S, Jacobson TA. Meta-analysis of comparison of effectiveness of lowering apolipoprotein B versus low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and nonhigh-density lipoprotein cholesterol for cardiovascular risk reduction in randomized trials. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 110(10): 1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thanassoulis G, Williams K, Ye K, et al. Relations of change in plasma levels of LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apoB with risk reduction from statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000759–e000759. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, et al. Evacetrapib and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Vascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20): 1933–1942. doi : 10.1056/NEJMoa1609581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HPS3/TIMI55-REVEAL Collaborative Group, Bowman L, Hopewell JC, et al. Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients with Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13): 1217–1227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathiyakumar V, Park J, Quispe R, et al. Impact of Novel LDL-C Assessment on the Utility of Secondary Non-HDL-C and ApoB Targets in Selected Worldwide Dyslipidemia Guidelines. Circulation. March 2018:CIRCULATIONAHA. 117.032463. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sniderman AD, Wolfson C, Teng B, Franklin FA, Bachorik PS, Kwiterovich PO. Association of hyperapobetalipoproteinemia with endogenous hypertriglyceridemia and atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97(6):833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunzell JD, Schrott HG, Motulsky AG, Bierman EL. Myocardial infarction in the familial forms of hypertriglyceridemia. Metab Clin Exp. 1976;25(3):313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durrington PN, Hunt L, Ishola M, Kane J, Stephens WP. Serum apolipoproteins AI and B and lipoproteins in middle aged men with and without previous myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1986;56(3):206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kukita H, Hamada M, Hiwada K, Kokubu T. Clinical significance of measurements of serum apolipoprotein A-I, A-II and B in hypertriglyceridemic male patients with and without coronary artery disease. ATH. 1985;55(2):143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbir M, Wile D, Trayner I, Aber VR, Thompson GR. High prevalence of hypertriglyceridaemia and apolipoprotein abnormalities in coronary artery disease. Br Heart J. 1988;60(5):397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamarche B, Despres JP, Moorjani S, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Lupien PJ. Prevalence of dyslipidemic phenotypes in ischemic heart disease (prospective results from the Québec Cardiovascular Study). Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(17): 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ginsberg HN. The ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) Lipid trial: what we learn from subgroup analyses. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 Suppl 2(Supplement_2):S107–S108. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nordestgaard BG, Zilversmit DB. Comparison of arterial intimal clearances of LDL from diabetic and nondiabetic cholesterol-fed rabbits. Differences in intimal clearance explained by size differences. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9(2):176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Björnheden T, Babyi A, Bondjers G, Wiklund O. Accumulation of lipoprotein fractions and subfractions in the arterial wall, determined in an in vitro perfusion system. ATH. 1996;123(1-2):43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G, Rosengren B, Lopez F, Wiklund O, Bondjers G. Differential uptake of proteoglycan-selected subfractions of low density lipoprotein by human macrophages. The Journal of Lipid Research. 1990;31(8):1387–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gotto AM, Gorry GA, Thompson JR, et al. Relationship between plasma lipid concentrations and coronary artery disease in 496 patients. Circulation. 1977;56(5):875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al. Distribution of lipids in 8,500 men with coronary artery disease. Department of Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(17):1196–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hopkins PN, Brinton EA, Nanjee MN. Hyperlipoproteinemia type 3: the forgotten phenotype. Cvrr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16(9):440–19. doi: 10.1007/s11883-014-0440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marais D Dysbetalipoproteinemia: an extreme disorder of remnant metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015;26(4):292–297. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sniderman AD, De Graaf J, Thanassoulis G, Tremblay AJ, Martin SS, Couture P. The spectrum of type III hyperlipoproteinemia. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2018; 12(6): 1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsimikas S A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(6):692–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, et al. Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):503–512. doi : 10.1056/NEJMoa1109034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willeit P, Ridker PM, Nestel PJ, et al. Baseline and on-statin treatment lipoprotein(a) levels for prediction of cardiovascular events: individual patient-data meta-analysis of statin outcome trials. Lancet. 2018;392( 10155):1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Donoghue ML, Fazio S, Giugliano RP, et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 Inhibition, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2019;139(12): 1483–1492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langsted A, Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. High lipoprotein(a) as a possible cause of clinical familial hypercholesterolaemia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(7):577–587. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paquette M, Bernard S, Thanassoulis G, Baass A. LPA genotype is associated with premature cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. April 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G. ApoB-100 Lipoprotein Complex Formation with Intima Proteoglycans as a Cause of Atherosclerosis and Its Possible Ex Vivo Evaluation as a Disease Biomarker. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2018. July 1 ;5(3). pii: E36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Younis N, Sharma R, Soran H, Chariton-Menys V, Elseweidy M, Durrington PN. Glycation as an atherogenic modification of LDL. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(4):378–384. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328306a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ketelhuth DFJ, Hansson GK. Adaptive Response of T and B Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118(4):668–678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MSSS. Repértoire Québécois Et Systéme De Mesure Des Procédures De Biologie Médicale — Édition 2019–2020 La Direction des communications du ministére de la Santé et des Services sociaux. 2019. msss.gouv.qc.ca section, Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 68.AACC Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices, Cole TG, Contois JH, et al. Association of apolipoprotein B and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy-derived LDL particle number with outcomes in 25 clinical studies: assessment by the AACC Lipoprotein and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices. Clin Chem. 2013;59(5):752–770. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.196733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Langlois MR, Chapman MJ, Cobbaert C, et al. Quantifying Atherogenic Lipoproteins: Current and Future Challenges in the Era of Personalized Medicine and Very Low Concentrations of LDL Cholesterol. A Consensus Statement from EAS and EFLM. Clin Chem. 2018;64(7): 1006–1033. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.287037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]