Abstract

Ultrasound (US) is an attractive diagnostic approach to identify both common and uncommon nipple pathologies, such as duct ectasia, nipple abscess, nipple leiomyoma, nipple adenoma, fibroepithelial polyp, ductal carcinoma in situ (restricted to nipple), invasive carcinoma, and Paget's disease. US is the reliable first-line imaging technique to assess nipple pathologies. It is useful to identify and characterize nipple lesions. Additionally, we have presented the mammography and MRI outcomes correlated with histopathologic features for the relevant cases.

Keywords: Nipple, Ultrasound, Nipple leiomyoma, Nipple adenoma, Nipple ductal carcinoma in situ, DCIS, Paget's disease

INTRODUCTION

The nipple is an intricate anatomic structure with unique characteristics when compared to other parts of the breast. It is comprised of lactiferous ducts lined by stratified squamous epithelium and dense fibrous stroma with smooth muscle tissue and sebaceous glands (1,2). Pathological processes can arise from any of these structures.

Clinical Examination

Most patients with nipple pathologies typically present with the associated symptoms upon clinical examination (3). The magnifying lamp is a useful tool to inspect nipple discharge and changes in nipple skin, shape, volume, and symmetry. Characteristically, a bilateral or long-standing nipple retraction is benign, while the presence of an acquired unilateral nipple inversion implies an underlying malignancy and should be evaluated with various imaging techniques. Furthermore, a benign process is indicated by a central, slit-like nipple retraction, while malignancy typically produces whole nipple inversion associated with areola distortion (2). Skin changes include erythema, ulceration, edema or satellite skin nodules. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish malignant from benign inflammatory skin changes through a visual inspection (4). Skin changes in breast cancer patients are of prognostic importance, as they function as indicators of upstage to locally advanced cancer (stage T4b) (5).

Imaging assessment of the nipple entails various imaging techniques, such as mammography, ultrasound (US), and MRI. Although a routine mammography has a limited role in evaluating the nipple, it cannot be replaced due to its necessity in identifying calcifications in the breast. Currently, US and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are applied to ensure a higher diagnostic accuracy (6,7,8,9). US is a necessary technique to assess nipple pathology since it can be used to identify and characterize nipple lesions, distinguish benign and malignant lesions, and guide the management of nipple pathology by facilitating US-guided percutaneous biopsy or planning the surgical excision of the lesion(s). US examinations often involve the use of a linear, high frequency transducer (17–5-MHz) that provides excellent superficial soft tissue resolution (10).

The nipple is always assessed bilaterally, using a generous amount of jelly, and visualizing the tissues in the transverse and longitudinal scan planes. If an intraductal lesion is suspected, a radial scan should be performed to apply different angles of the transducer, until the probe is placed parallel to the long axis of the intraductal lesion. Successive compression on the distal and proximal ends of the transducer flattens the nipple to display the extent of the involved duct and its connection to the nipple (11,12).

Doppler mode, strain, and shear-wave elastography increase the specificity of conventional B-mode US and improve its diagnostic performance with regard to both benign and malignant breast lesions (10,13,14). The role of elastography for nipple evaluation is limited due to its superficial location. To the best of our knowledge, there are no currently available recommendations with regard to elastography acquisition for nipple evaluation. Here, we illustrate the importance of US in identifying the normal, benign, and malignant changes in the nipple that typically present as diagnostic difficulties for radiologists.

Normal Findings and Benign Pathology

Normal Nipple

Appearance of a normal nipple on US varies among individuals. Nipples frequently demonstrate a homogeneous echo-structure with milk that appear as linear hypo/isoechoic structures radiating from the nipple towards the breast. Occasionally, the nipple may display scattered hyperechoic foci because the walls of the terminal ducts are typically too small to be observed as tubular fluid-filled structures. The latter finding produces a “dots appearance” of the nipple. The variations in the nipple echo-structures can be attributed to differences in the wall thickness of the ducts and differences in the distribution of muscle fibers and connective tissues (Fig. 1). A nipple can be either hypovascular or hypervascular on color Doppler US. Vascular symmetricity a key feature to distinguish normal and pathological nipples. Furthermore, there may be nipple variations including the congenital nipple retraction or accessory nipple (polythelia). During pregnancy and lactation, the areolae and nipples appear darker and larger, due to the underlying benign changes such as nipple crack and erosions (15) (Fig. 2).

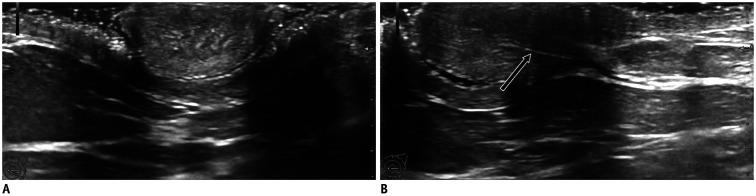

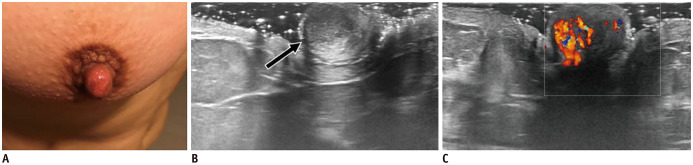

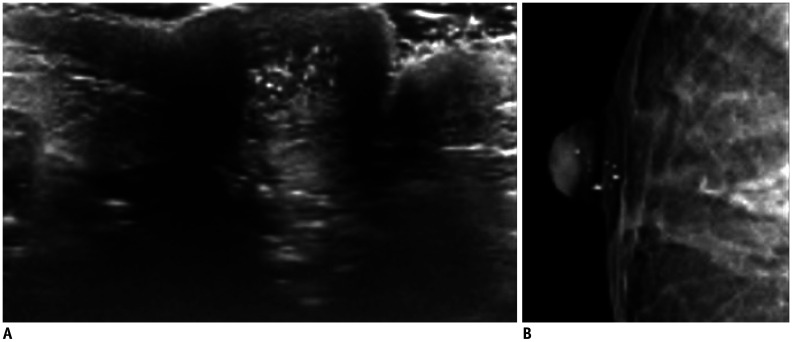

Fig. 1. Normal nipple US findings.

Nipple with homogeneous structure on axial (A) and longitudinal (B) planes, with visible longitudinal milk duct (B, arrow). US = ultrasound

Fig. 2. Polythelia and lactating nipple.

A. There is supernumerary nipple (arrow), located near right axilla, along embryonic milk lines, in consistence with polythelia. B. Darker areola and nipple with prominent Montgomery glands due to lactation.

Duct Ectasia

Although it is understood that the prevalence of duct ectasia in nonlactating women rises to 3% and is responsible for 41% of the nipple discharge symptoms in women (16), its associated etiology requires further elucidation. Duct ectasia is a nonspecific dilatation (> 2 mm diameter) of one or more ducts and is typically observed in combination with inflammation (galactophoritis), obstruction, or stasis. Duct excision can be considered in patients with persistent nipple discharge.

US reveals duct changes represented by dilated ducts with anechoic content, corresponding to a high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 3). Hypoechoic intraductal content is occasionally observed due to viscous secretions or underlying infections. Galactophoritis should be suspected in the presence of inflammatory symptoms (redness, tenderness, pain), and antibiotics should be promptly administered (Fig. 4).

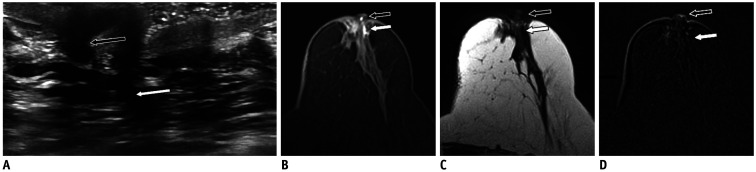

Fig. 3. Duct ectasia.

70-year-old woman presented with bloody nipple discharge.

A. US shows dilated ducts within left nipple (black arrow) and retroareolar space (white arrow). Dilated ducts have intermediate T2-weighted signal (C, arrows) and hyperintense signal on T1-weighted fat-saturation non-enhanced image (B, arrows) consistent of blood products. D. No intraductal mass was noted on subtracted enhanced T1-weighted sequence (arrows). Patient refused duct excision and opted for short-term follow-up.

Fig. 4. Galactophoritis.

51-year-old woman presented with serous nipple discharge and nipple pain. US shows dilated duct within left nipple, with hypoechoic content and absent vascularity (arrow). Patient underwent antibiotics therapy with complete resolution of symptoms after 7 days.

The hypoechoic intraductal content may mimic an intraductal mass (15). In such cases, it is useful to apply repetitive pushing maneuvers on the duct, forcing the viscous secretions to move back and forth within the duct lumen. Color Doppler US is used to distinguish between secretions and intraductal neoplasms. Although secretions do not show internal vascularity, an intraductal neoplasm has internal vascular flow and does not move when subjected to the pushing maneuvers. Scanning duct ectasia is usually accompanied by finding an intraductal neoplasm (Fig. 5). Histological confirmation is imperative when an intraductal neoplasm is suspected, regardless of its location.

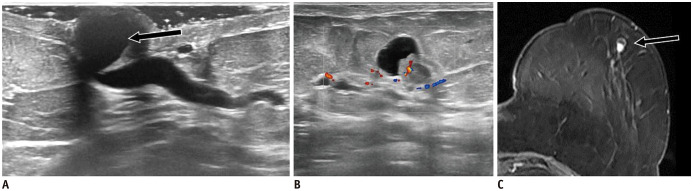

Fig. 5. Nipple ectasia combining intraductal neoplasm.

62-year-old woman presented with bloody nipple discharge.

A. US shows dilated duct within nipple (arrow), which extends into retroareolar area. B. Following duct ectasia, complex cystic-solid mass with internal vascularity is found in left-outer quadrant of breast. C. Lesion was confirmed on T1-weighted fat-saturation contrast-enhanced MRI sequence (arrow). Histology revealed intracystic papilloma (not shown).

Infection and Abscess

Lactating women are more susceptible to breast infections (mastitis), with the prevalence ranging from 1% to 10%, than non-lactating women (17). Breast abscesses, which develop as a complication of mastitis, are classified as lactation and non-lactation abscesses. A non-lactation abscess is observed in approximately 90% of the cases in the sub-areolar area and the nipple (17). An abscess is an accumulation of pus that arises due to an obstructed Montgomery gland. US imaging outcomes present abscesses as a round, iso-/hypoechoic, mass with circumscribed or indistinct margins. The mass is devoid of an internal flow, but demonstrates an intense vascular rim. MRI examinations reveal a T2 hyperintense cystic lesion exhibiting rim-enhancement on post-contrast sequences (Fig. 6). Due to superficial location of the nipple, the diffusion-weighted imaging/apparent diffusion coefficient features are not always reliable.

Fig. 6. Nipple abscess.

38-year-old woman presented with right milky nipple discharge.

A. US shows round, isoechoic and circumscribed mass within right nipple with vessels in rim (arrow). On MRI, mass is hyperintense on T2-weighted image (B, arrow), with complete rim enhancement on MIP image (C, arrow). D. Patient received antibiotics therapy and complete lesion's resolution was noted after 10 days. MIP = maximum intensity projection

Women with painful nipples may present with pseudo-solid looking masses with a vascular rim, which may have occurred due to inflammatory cysts, intra-nipple periductitis, or abscesses. It is not always possible to differentiate these three entities accurately; however, since the management modalities for all three are identical, their differentiation is not particularly important. The lesions respond to anti-inflammatory or antibiotic therapy and rarely require fine needle aspiration cytology.

Epidermal Inclusion Cyst

Epidermal inclusion cysts are the most common keratinous cysts of the skin (18), which arise from the sequestration of epidermal cells into the dermis through the continuous accumulation of keratin. US shows a round, hypoechoic mass with circumscribed margins and the absence of a vascular flow. Excision or percutaneous biopsy is occasionally necessary to differentiate epidermal inclusion cysts and tumors (Fig. 7).

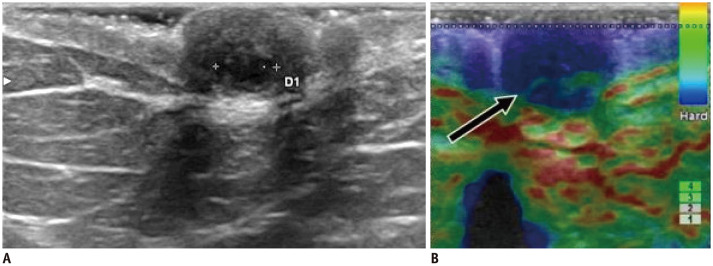

Fig. 7. Epidermal inclusion cyst of nipple.

43-year-old women presented with left painful nipple.

A. US reveals round, hypoechoic, circumscribed mass with acoustic enhancement located within nipple. B. Mass is more clearly delineated on elastography (arrow), latter with limited value due to lesion's superficial location.

Eczema

The prevalence of nipple and areola eczema is currently unknown. Because it typically affects both nipples, unilateral involvement of the same is rarely reported. Eczema has two forms: acute–a “wet” erythematous eruption with vesicles and sub-acute or chronic–a dry, erythematous, and lichenified dermatitis (19).

Eczema may appear as a minor manifestation of atopic dermatitis (AD). However, there are no reported differences regarding its degree of severity, inflammation pattern or immunohistochemical findings between patients with or without AD (20). US reveals skin changes, such as skin thickening and increased vascularity on color Doppler US, in the areolar region. The findings might be responsive to topical application of steroids (Fig. 8). Unilateral eczema may clinically resemble Paget's disease, but it initially involves only the areola and later progresses to the nipple. Contrarily, Paget's disease spreads outwards from the nipple. If the symptoms and US findings do not improve after steroidal administration, a biopsy to exclude Paget's disease is warranted (2,21).

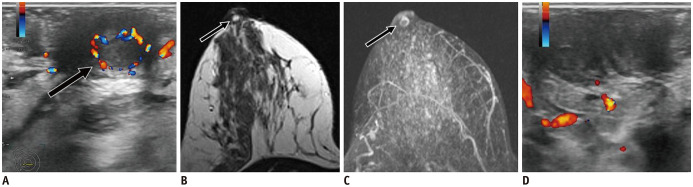

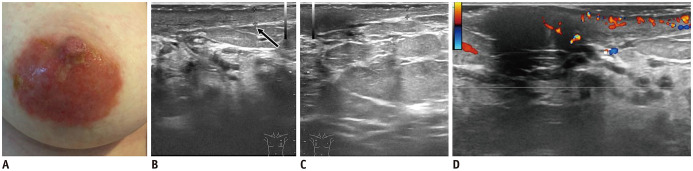

Fig. 8. Acute eczema of nipple.

A. 46-year-old woman presented with redness, small vesicles, and pain in left nipple-areola complex. US shows skin thickening on left side (B) compared with right side (C, arrow), along with increased vascularity in nipple and areola region (D). Patient's symptoms improved after 3 weeks of topical application of steroid cream.

Other nipple pathologies may present with eczematous features, such as psoriasis, allergic contact dermatitis, and infections (Fig. 9).

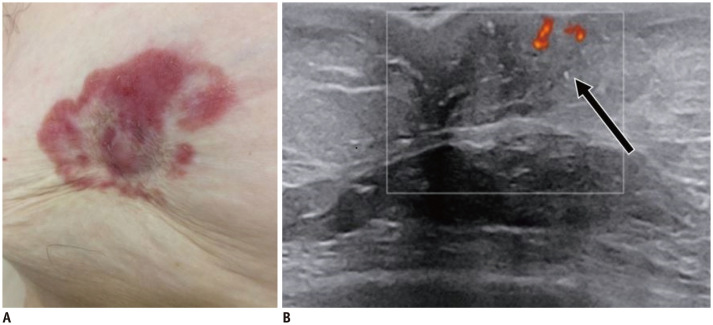

Fig. 9. Chronic eczema of nipple.

A. 66-year-old woman known with psoriasis, presented with red excoriations involving right nipple-areolar complex for 10 years. Patient has positive history of right breast surgery with benign histology. B. US shows nipple retraction and subtle skin thickening, with internal vascularity (arrow).

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas of the nipple-areola complex are the least common subtype of genital-leiomyomas, with only 50 previously described cases (22). It is a slow growing benign tumor of smooth muscles and it affects one or both nipples and represents a potential cause of inflammation and chronic nipple pain (23). US shows an oval, circumscribed hypoechoic mass with internal vascularity, whereas an MRI scan reveals an intense, homogeneous enhancement in the mass (Fig. 10). Excisional biopsy is generally performed for histological confirmation.

Fig. 10. Nipple leiomyoma.

48-year-old woman presented with nipple tenderness.

A. US reveals oval, hypoechoic, circumscribed mass located within nipple, with acoustic enhancement and internal vascularity. B. T1-weighted subtraction image reveals focal enhancement of nipple corresponding to US mass (arrow). Patient underwent surgery with histology result of leiomyoma.

Fibroepithelial Polyp

Fibroepithelial polyp is an extremely rare benign tumor that typically occurs in the skin, oral cavity, and genitourinary tract. Previously, there have been a few cases on nipple fibroepithelial polyps (24,25). Histologically, polyps are superficial lesions covered by squamous epithelium, with spindle, stellate and stromal giant cells. It is difficult to distinguish them from metaplastic-spindle cell carcinoma based on biopsy samples alone. An MRI scan may be used to assess the polyp's extension and to plan the excisional biopsy (Fig. 11).

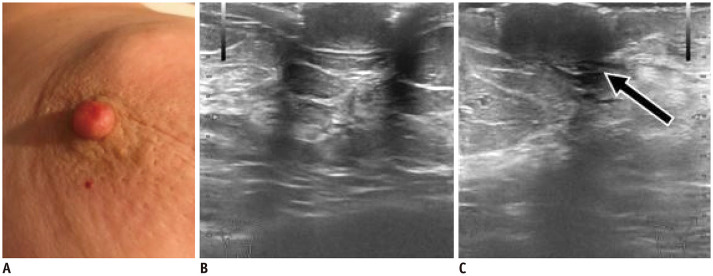

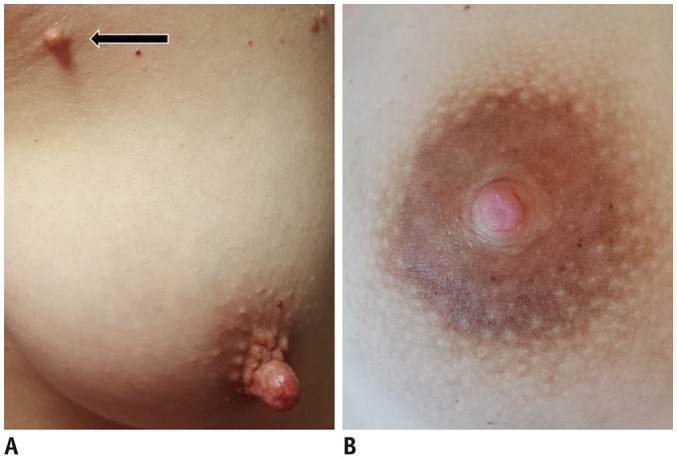

Fig. 11. Fibroepithelial polyp.

A. 25-year-old patient presented with polypoid lesion involving left nipple. B. US shows irregular, iso-/hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins and with vascular pedicle. C. On MRI, MIP images reveal mass with intense enhancement located in nipple (arrow). Consequently, surgical excision of polyp and nipple was performed.

Adenoma

Nipple adenoma is an uncommon benign tumor with unknown prevalence. Histologically, an epithelial proliferation with a retained myoepithelial cell layer occupies the surrounding stroma of lactiferous ducts (3). Clinically, it manifests as a palpable nipple nodule or simulates Paget disease and it is rarely associated with bloody nipple discharge. It is visualized as a round, homogeneous, hypoechoic mass with circumscribed margins and intense vascularity on US (26) (Fig. 12). Nipple skin punch biopsy confirmation and subsequent surgical excision remain the gold standard to diagnose and treat adenoma, similar to all benign nipple tumors (26).

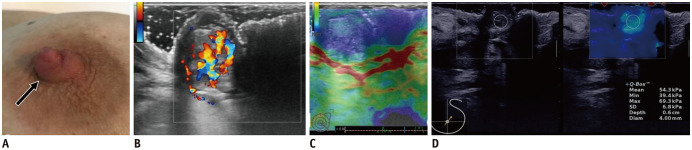

Fig. 12. Nipple adenoma.

A. 40-year-old woman presented with nipple erythema for 6 months. US shows round, isoechoic and circumscribed nipple mass (B, arrow), with internal vascularity (C). Patient underwent surgery with histology result of adenoma.

Central Papilloma

Intraductal papillary lesions (papilloma) are breast tumors that are observed in 2–3% of women between ages of 30 to 77 years (27). These are classified into central and peripheral types. Central papillomas arise in the subareolar space and are usually solitary, whereas the latter tend to occur in clusters. Approximately 57% of the patients with breast papilloma present with spontaneous, unilateral, bloody nipple discharge, with a higher incidence of central papillomas. Apart from the fact that a central papilloma arises within major ducts and peripheral papilloma occupy the terminal ductules, both types demonstrate identical histological characteristics, which include an intraductal proliferation of epithelial and myoepithelial cells overlying a fibro-vascular stalk (28). Unlike adenoma secretions, which are discharged into a confined space outside the ducts, the papilloma mucus-secretions are inside the ducts (12,21). The epithelial component may harbor a wide spectrum of morphologic changes ranging from hyperplasia to metaplasia, atypical intraductal hyperplasia, and in situ carcinoma (28). Compared to peripheral papilloma, a central papilloma is less associated with a coexisting malignancy (27).

Benign and malignant papillomas have similar US findings and may present as either a mass, a complex cystic-solid mass or duct changes only; all presentations show internal vascularity. MRI examinations reveal the presence or absence of a mass or non-mass enhancement (NME, focus type) depending on their size, and are rarely MRI occults (up to 2%) (29). A mass exceeding 10 mm, a mixed mass-NME lesion, and the segmental/regional distribution of the NME lesions are findings more commonly observed in high-risk papilloma or malignant lesions than in benign papilloma (29) (Figs. 13, 14, 15). Since imaging criteria alone are not sufficient to exclude the possibility of a malignant tumor, a percutaneous needle biopsy followed by surgical excision, is usually recommended for cases diagnosed with papilloma.

Fig. 13. Papilloma—mass.

A. 37-year-old patient presented with left palpable nipple nodule (arrow). B. US shows oval, isoechoic and circumscribed mass with internal vascularity. While strain elastography has limited value (C), shear-wave elastography reveals mass's stiffness (max stiffness = 69.3 kPa) (D). Patient underwent surgery with histology result of benign papilloma.

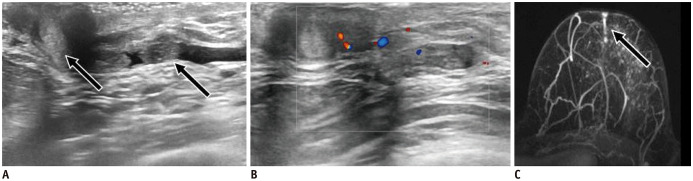

Fig. 14. Papilloma—complex cystic-solid mass.

55-year-old patient presented with bloody nipple discharge. US shows complex cystic and solid mass inside nipple and discrete retroareolar duct ectasia with hypoechoic content and internal vascularity (arrow). Patient underwent surgery, which proved that complex cystic mass and duct content were small papillomas.

Fig. 15. Papilloma—intraductal mass.

46-year-old patient presented with bloody nipple discharge.

US shows nipple dilated duct with hypoechoic content, which extends into retroareolar area (A, arrows) and has intraductal vascularity (B). C. MIP image (arrow) displays linear, non-mass enhancement corresponding to duct content. Patient underwent surgical excision of duct with histology result of papillomas.

Malignant Pathology

Primary Invasive Carcinomas of Nipple

Approximately 8% of breast cancers develop within the central part of the breast (2). Two cancer types involve the nipple: primary (developing within the nipple) and secondary carcinomas (breast tumors that spread towards nipple). The amount of published information on nipple primary carcinomas is considerably lacking apart from that on Paget's disease. Nipple cancers are difficult to detect, as they are usually confused with normal nipple structures (15). A recent paper reported that 50% of the primary nipple carcinomas are ductal, 21% of them are lobular, and 29% of cancers have mixed ductal and lobular features (30).

US findings of primary ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the nipple overlap with that of benign nipple tumor masses (Figs. 16, 17).

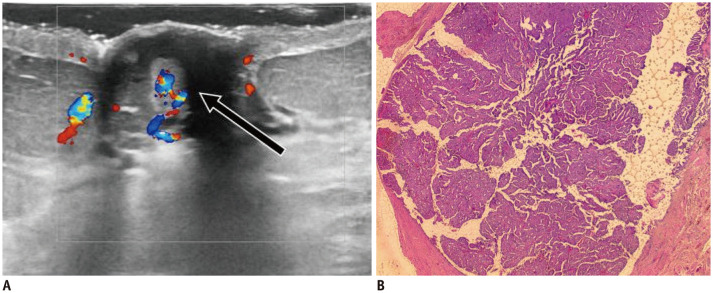

Fig. 16. DCIS—mass.

75-year-old patient presented with bloody nipple discharge.

A. US shows irregular, hypoechoic nipple mass with indistinct margins and internal vascularity (arrow). B. After surgery, histology (hematoxylin and eosin stain × 2.5) reveals papillary lesion inside dilated duct, with areas of malignant transformation-DCIS with nuclear grade 2 foci. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ

Fig. 17. DCIS—microcalcifications.

Images of asymptomatic patient.

US shows scattered echogenic foci (A) confirmed by mammography (B) as microcalcifications. After positive MRI (not shown), patient underwent surgery with pathology result of DCIS.

US features of primary invasive carcinoma of the nipple are as follows: 1) swollen nipple, usually homogeneously hypoechoic with intense vascularity compared to a contralateral; 2) irregular mass with iso-/ hypoechoic echo-pattern, indistinct or spiculated margins, shadowing, and internal vascularity; 3) complex cystic-solid mass; 4) duct changes, with duct ectasia and intraductal microcalcifications/hypoechoic content with internal vascularity; and 5) microcalcifications (Figs. 18, 19).

Fig. 18. IDC—swollen nipple.

A. 68-year-old patient presented with erosion on left swollen nipple. US reveals larger, homogeneous and hypoechoic left nipple (C, arrow) compared to right one (B). Additional suspicious mass was seen in left outer quadrant of left breast (not shown). Patient underwent surgery with pathology result of IDC no special type nuclear grade 3, estrogen receptor = 70%, progesterone receptor = 30%, Ki-67 = 35%, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 = +3, involving nipple. IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma

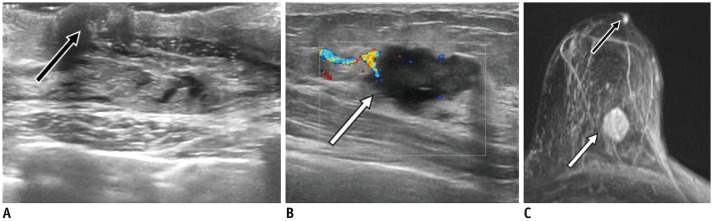

Fig. 19. IDC—ductal changes.

60-year-old patient presented with bloody nipple discharge.

A. US shows dilated ducts involving nipple and retroareolar region (black arrow) with hypoechoic content. Mammography (not shown) excluded presence of microcalcifications. B. Additional irregular, hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins and internal vascularity is detected in left outer quadrant of same breast (white arrow). C. MRI (arrows) identifies two US findings; small focus-type nipple lesion and the second, larger mass in outer quadrant. Histology highlighted IDC for both lesions.

Paget's Disease

Paget's disease accounts for less than 3% of all breast carcinoma, and is characterized by the presence of malignant cells within the squamous epithelium of the nipple (19). It may consist of a single self-standing nipple malignancy, or it may be associated with DCIS and invasive carcinoma (invasive ductal carcinoma [IDC] in more than 80% of cases), both in proximity of or distant from the nipple (31).

The differential diagnoses should include other pathologies including eczema, Bowen's disease, melanoma, or breast carcinoma involving the nipple by contiguity or invasion (31).

Clinical examination may reveal subtle skin changes (erythema or ulceration) as the only sign of Paget's disease. US should be included in the initial diagnostic evaluation, especially upon a negative mammography outcome. US findings include nipple asymmetry, nipple flattening, or skin thickening, the presence of a mass, microcalcifications, or duct changes within the nipple (32). MRI is recommended in patients with Paget's disease. In addition to skin thickening and/or asymmetrical nipple enhancement, presence of underlying parenchymal DCIS or IDC should be evaluated with MRI (Fig. 20). Paget's disease is usually diagnosed on nipple punch biopsies. Surgical planning regarding the feasibility of conservative surgery is decided based on presence and extent of parenchymal DCIS or IDC on MRI.

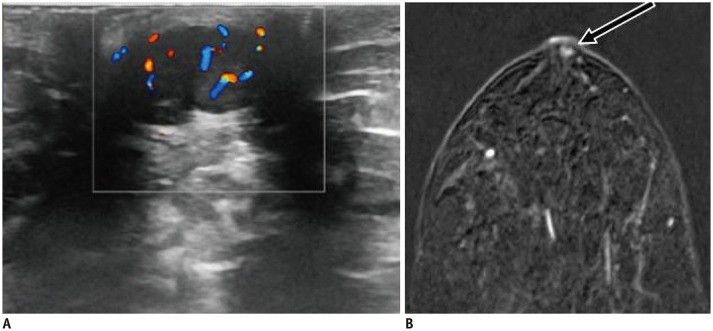

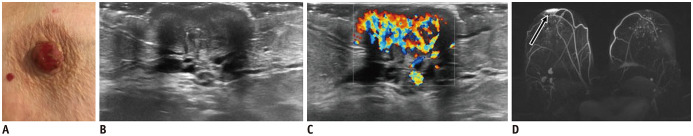

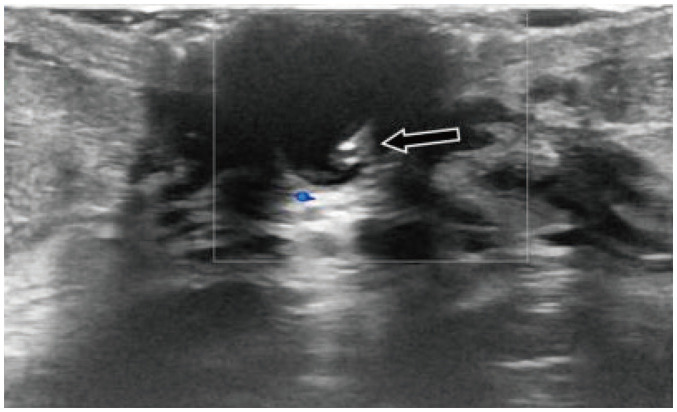

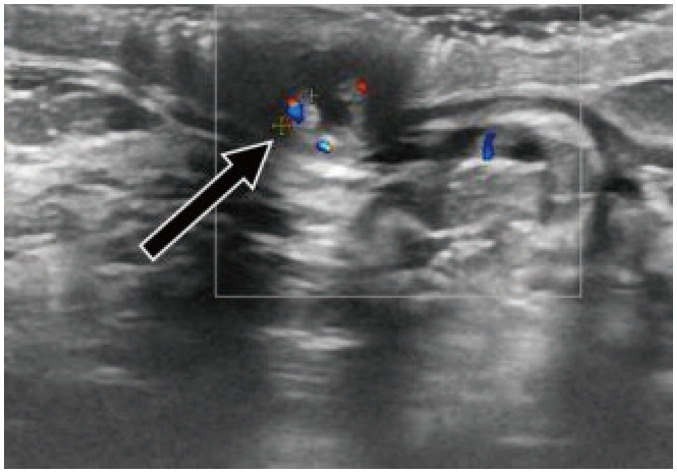

Fig. 20. Paget's disease.

A. 84-years-old patient presented with erosions and swollen right nipple. US reveals globally enlarged nipple (B) with internal vascularity (C). D. MIP image highlights asymmetrical enhancement of right nipple (arrow). Punch biopsy confirmed Paget's disease of nipple.

The main imaging differences between inflammatory nipple lesion, benign tumor, and nipple malignancy are presented in Table 1. The histology and US findings of all aforementioned nipple pathologies are listed in Table 2.

Table 1. US Findings of Inflammatory Lesions, Benign Tumors, and Invasive Cancer of Nipple.

| Us Findings | Inflammatory Nipple Lesion | Benign Tumor | Invasive Malignancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masses | |||

| Shape | Round/oval | Round/oval | Irregular |

| Echo-pattern | Hypo-/isoechoic | Hypo-/isoechoic | Hypoechoic |

| Margins | Circumscribed/indistinct | Circumscribed | Indistinct/spiculated |

| Posterior features | - | - (enhancement) | - (shadowing) |

| Vascularity | + (rim vessels) | + | + |

| Ductal changes | |||

| Dilated duct | + | + | + |

| Content | +/- hypoechoic | + hypoechoic | +/- hypoechoic +/- calcifications |

| Vascularity | + (periductal) | + (intraductal) | + (intraductal) |

| US short-term follow-up | Completely absent/small size | No change/same size | No change/increasing size |

US = ultrasound, + = present, − = absent

Table 2. Benign and Malignant Nipple Pathologies.

| Pathologies | Histologic Features | Imaging Features | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-Mode | Color Doppler Mode (Vascularity) | |||

| Duct ectasia | Nonspecific duct dilatation (> 2 mm) | Duct changes | - | Antibiotics, duct excision |

| Abscess | Localized collection of pus | Circumscribed/non-circumscribed mass | + (vessels in rim) | Antibiotics |

| Epidermal inclusion cyst | Keratin containing cyst | Circumscribed mass + enhancement | - | Surgery |

| Eczema | Skin edema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration | Thickening of skin > 2 mm | + | Topical steroids |

| Leiomyoma | Smooth muscle cell benign tumor | Circumscribed mass + enhancement | + | Surgery |

| Fibroepithelial polyp | Superficial polyp | Mass on skin | + (vascular pedicle) | Surgery |

| Adenoma | Benign epithelial proliferation located outside ducts | Circumscribed/non-circumscribed mass + enhancement | + | Surgery |

| Papilloma | Benign intraductal epithelial proliferation | • Circumscribed mass | + | Surgery |

| • Complex cystic-solid mass | + | |||

| • Duct changes | + | |||

| Invasive primary carcinomas | In situ/invasive carcinomas | • Swollen nipple* | + | Surgery +/- |

| - malignant cells originating in ducts (50%), lobules (21%) or both (29%) | • Non-circumscribed mass +/- shadowing | + | Chemo-/Radiotherapy | |

| • Complex cystic-solid mass | + | |||

| • Duct changes | + | |||

| • Microcalcifications | - | |||

| Paget's disease | Malignant cells within squamous epithelium of nipple | • Nipple asymmetry +/- nipple flattening +/- skin thickening | +* | Surgery +/- |

| • Non-circumscribed mass | + | Radiotherapy | ||

| • Duct changes | + | |||

| • Microcalcifications | - | |||

*Findings compared to contralateral nipple. + = internal vascularity present, − = internal vascularity absent

CONCLUSION

Summarily, nipples may be affected by various benign and malignant pathologies, several of which have similar clinical and imaging presentations. US is the first-line imaging examination to characterize and identify nipple lesions with a non-invasive and practical approach. Appropriate US technique to evaluate nipple pathology is crucial. Inflammatory lesions often display a peripheral vascularity (periductal), while tumor masses show internal vascularity. An irregular, hypoechoic mass with spiculated margins and shadowing in nipple suggests the possibility of invasive carcinoma of the nipple. DCIS and benign tumors (papilloma, adenoma) have overlapping US findings.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Pandya S, Moore RG. Breast development and anatomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:91–95. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318207ffe9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson BT, Harvey JA, Cohen MA. Nipple-areolar complex: normal anatomy and benign and malignant processes. Radiographics. 2009;29:509–523. doi: 10.1148/rg.292085128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel BK, Falcon S, Drukteinis J. Management of nipple discharge and the associated imaging findings. Am J Med. 2015;128:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldman RA, Finch J, Grant-Kels JM, Stevenson C, Whitaker-Worth D. Skin diseases of the breast and nipple: benign and malignant tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1467–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson FM, Bondy M, Yang W, Yamauchi H, Wiggins S, Kamrudin S, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: the disease, the biology, the treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:351–375. doi: 10.3322/caac.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahl M, Gadd MA, Lehman CD. Journal Club: diagnostic utility of MRI after negative or inconclusive mammography for the evaluation of pathologic nipple discharge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:1404–1410. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yılmaz R, Bender Ö, Çelik Yabul F, Dursun M, Tunacı M, Acunas G. Diagnosis of nipple discharge: value of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography in comparison with ductoscopy. Balkan Med J. 2017;34:119–126. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.2016.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahl M, Baker JA, Greenup RA, Ghate SV. Diagnostic value of ultrasound in female patients with nipple discharge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:203–208. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubina N, Schedelbeck U, Roth A, Weng AM, Geissinger E, Hönig A, et al. 3.0 tesla breast magnetic resonance imaging in patients with nipple discharge when mammography and ultrasound fail. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:1285–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooley RJ, Scoutt LM, Philpotts LE. Breast ultrasonography: state of the art. Radiology. 2013;268:642–659. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavros AT. Breast anatomy: the basis for understanding sonography. In: Stavros AT, editor. Breast ultrasound. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 56–108. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon JH, Yoon H, Kim EK, Moon HJ, Park YV, Kim MJ. Ultrasonographic evaluation of women with pathologic nipple discharge. Ultrasonography. 2017;36:310–320. doi: 10.14366/usg.17013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SH, Chang JM, Cho N, Koo HR, Yi A, Kim SJ, et al. Practice guideline for the performance of breast ultrasound elastography. Ultrasonography. 2014;33:3–10. doi: 10.14366/usg.13012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Chang JM, Kim WH, Bae MS, Seo M, Koo HR, et al. Added value of shear-wave elastography for evaluation of breast masses detected with screening US imaging. Radiology. 2014;273:61–69. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu JH, Kim MJ, Cho H, Liu HJ, Han SJ, Ahn TG. Breast diseases during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:143–159. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiu CM, Chiou SY, Chou YH, Lai CH, Chiou HJ, Chiang HR, et al. Clinical significance of ductal dilatation on breast ultrasonogram. J Med Ultrasound. 2005;13:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon JM. Breast infection. BMJ. 2013;347:f3291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dilek N, Dilek AR, Saral Y, Şehitoğlu I. Epidermoid cyst on the nipple: a rare location. Breast J. 2014;20:203–204. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geffroy D, Doutriaux-Dumoulins I. Clinical abnormalities of the nipple-areola complex: the role of imaging. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song HS, Jung SE, Kim YC, Lee ES. Nipple eczema, an indicative manifestation of atopic dermatitis? A clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:284–288. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Costa D, Taddese A, Cure ML, Gerson D, Poppiti R, Jr, Esserman LE. Common and unusual diseases of the nipple-areolar complex. Radiographics. 2007;27 Suppl 1:S65–S77. doi: 10.1148/rg.27si075512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gokdemir G, Sakiz D, Koslu A. Multiple cutaneous leiomyomas of the nipple. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:468–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura S, Hashimoto Y, Takeda K, Nishi K, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Mizumoto T, et al. Two cases of male nipple leiomyoma: idiopathic leiomyoma and gynecomastia-associated leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:287–291. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31822a3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaaban AM, Turton EP, Merchant W. An unusual case of a large fibroepithelial stromal polyp presenting as a nipple mass. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:345. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belli AK, Somuncu E, Aydogan T, Bakkaloglu D, Ilvan S, Aydogan F. Fibroepithelial polyp of the nipple in a woman. Breast J. 2013;19:111–112. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spohn GP, Trotter SC, Tozbikian G, Povoski SP. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4. doi: 10.1186/s12895-016-0041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganesan S, Karthik G, Joshi M, Damodaran V. Ultrasound spectrum in intraductal papillary neoplasms of breast. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:843–849. doi: 10.1259/bjr/69395941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oyama T, Koerner FC. Noninvasive papillary proliferations. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2004;21:32–41. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang LJ, Wu P, Li XX, Luo R, Wang DB, Guan WB. Magnetic resonance imaging features for differentiating breast papilloma with high-risk or malignant lesions from benign papilloma: a retrospective study on 158 patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:234. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1537-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders MA, Brock JE, Harrison BT, Wieczorek TJ, Hong X, Guidi AJ, et al. Nipple-invasive primary carcinomas: clinical, imaging, and pathologic features of breast carcinomas originating in the nipple. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:598–605. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0226-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geffroy D, Doutriaux-Dumoulins I, Labbe-Devilliers C, Meingan P, Houdebine S, Sagan C, et al. [Paget’s disease of the nipple and differential diagnosis.] J Radiol. 2011;92:889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jradio.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim HS, Jeong SJ, Lee JS, Park MH, Kim JW, Shin SS, et al. Paget disease of the breast: mammographic, US, and MR imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2011;31:1973–1987. doi: 10.1148/rg.317115070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]