Abstract

Background

Sexual and gender minority individuals may have different lifetime risk of skin cancer and ultraviolet radiation exposure than heterosexual persons.

Objective

To systematically review the prevalence of skin cancer and behaviors that increase risk of skin cancer among sexual and gender minority populations.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature review in PubMed/Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and World of Science searching for articles through October 18, 2019 that investigated risk of skin cancer and behaviors among sexual and gender minority populations.

Results

SMM have a higher lifetime risk of any skin cancer (OR range: 1.3–2.1) and indoor tanning bed use (OR range: 2.8–5.9) when compared to heterosexual men, while SMW may use indoor tanning beds less frequently than heterosexual women and do not have an elevated risk of lifetime history of skin cancer. Gender-nonconforming individuals have higher lifetime prevalence of any skin cancer compared to cisgender men.

Limitations

Most variables rely on self-reporting in their original studies.

Conclusions

SMM disproportionately engage in use of indoor tanning beds which may result in increased lifetime risk of skin cancer. Recognition of this risk is important for providing appropriate screening for patients in this population.

Capsule Summary

● Recent evidence shows that sexual minority populations may disproportionately engage in skin cancer risk behaviors.

● Sexual minority men have a higher prevalence of both skin cancer and indoor tanning bed use compared to heterosexual men, which likely reflects unique community pressures and appearance ideals in this community.

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, with roughly 4.9 million people treated annually.1 Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is one of the environmental risk factors; most strongly associated with development of both melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas, with both outdoor sun exposure2–4 and indoor tanning bed use5,6 conferring substantial risk.

There is increasing national focus on health disparities facing sexual and gender minority populations, with a recent call for further research into specific cancer risks and risk factors.7 Sexual minorities include, but are not limited to, those who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, while gender minority is an umbrella term that includes transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender persons have a gender identity that is distinct from their sex assigned at birth, while gender-nonconforming individuals identify as neither male nor female or as having features of both sexes.

Sexual minority men (SMM) may be at increased risk of indoor tanning, as negative body image is linked to indoor tanning bed use and sexual minority men report lower body satisfaction than heterosexual men.9 Though there is increasing national attention on cancer risks among gender minority individuals,7 not much is known about skin cancer risk behaviors in this population.

In this study, we aimed to review the data on the prevalence of skin cancer and skin cancer risk behaviors among sexual and gender minority populations.

Methods

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.10

Eligibility Criteria

We included all studies whose primary focus was to assess the risk of either skin cancer or skin cancer risk behavior among sexual and gender minority communities. Case reports, letters to the editor, opinion pieces, and abstracts were excluded from our analysis, as were studies that focused on skin cancer risk among HIV-positive patients without specific consideration of sexual minority status. There were no language, date, or country restrictions for included studies.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases through October 18, 2019 for all research articles. Search terms included both terms used to describe the LGBT community and terms related to skin cancer and skin cancer risk behaviors. A full list of search terms can be found in the Supplement. Our study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (#CRD42019116879).

Study Selection

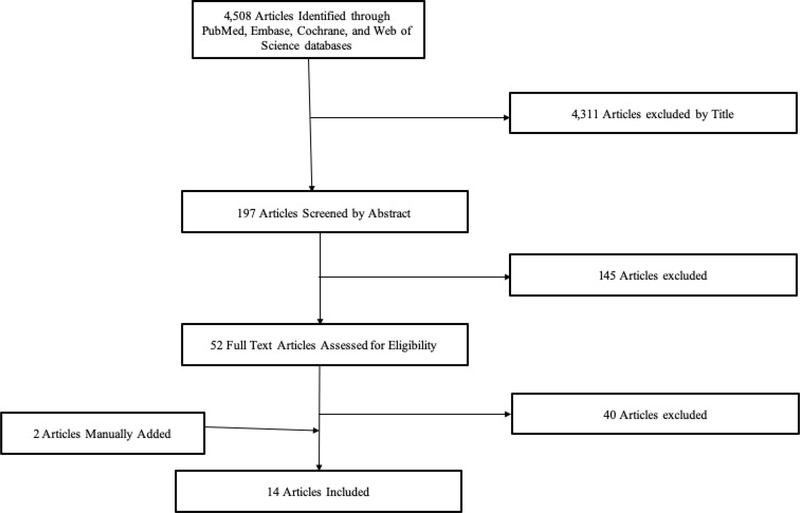

Two reviewers (S.S. and E.T.) independently screened all titles and abstracts. For articles that met inclusion criteria after abstract review, full text review was also performed. Two studies were manually added as they were published shortly after our initial search was performed. A third reviewer (A.M.) mediated disagreement between reviewers and approved the final list of included studies. Study quality was assessed using a quality assessment checklist for studies assessing prevalence.11

Results

Selection of Studies

Our initial search identified 4,508 articles. Of those, 4,311 were excluded based on title and an additional 145 were excluded after review of title and abstract. 52 full text articles were ultimately reviewed for inclusion, with 12 meeting inclusion criteria for our study. Two additional studies written by our research group that are currently in-press were added, resulting in 14 total articles being included in our study sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search and Selection Strategy of Relevant Articles.

Of the studies included, 2 included results from population-based prospective cohort studies, 7 from population-based cross-sectional studies, 4 from regional survey studies, and 1 from a focus group study (Table 1). Though we did not restrict our search to domestic studies, all studies identified were from the United States. The studies varied in age group, as 9 included exclusively adults and 5 included only adolescents and young adults.

Table 1:

Study Characteristics and Outcomes

| Source | Age Limitation | Study Design | Population-Based Sample (yes/no) | Study Population | Groups | Outcome(s) | Major Finding(s) | Assessment of Risk of Bias** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admassu et al, 2019 | ≥18 | Qualitative: Focus Groups | No | SMM in San Francisco, CA who had used indoor tanning at least once | 38 gay men; 7 bisexual men; 3 other sexual orientation | • Reasons for starting and stopping indoor tanning | Aesthetic concerns and community pressures were the primary motivations for indoor tanning, while skin ageing and skin cancer risk were among the top motivations for stopping. | Moderate Risk |

| Blashill et al., 2014 | 16–29 | Prospective cohort study | Yes | Male respondents of National Longitudinal Adolescent Health Study | 78 MM; 1689 heterosexual men | • History of indoor tanning ever • Sunbathing history • Sunscreen use |

SMM have higher rates of indoor tanning at age 16 (OR = 3.9) | Moderate Risk |

| Blashill et al., 2017 | 9th to 12th graders. In high school* | Cross-sectional study | Yes | 9th to 12th grade respondents of 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 354 SMMs; 5,013 heterosexual males; 886 SMWs; 4,391 heterosexual females | • Indoor tanning bed use (by race) | Both sexual minority status and male sex independently increase odds of indoor tanning | Low Risk |

| Blashill et. al, 2018 | 15–35 | Survey study | No | Online survey of SMM in San Diego, California | 231 SMM (84% gay, 11.3% bisexual, 0.4% asexual, 0.4% heterosexual, 3.8% “Other”) | • Reasons/motivations for indoor tanning • Future intention to indoor tan • Perceived skin cancer risk |

Higher perceived skin cancer risk associated with decreased intent to indoor tan. Social pressures and association of tanning with affect regulation increased likelihood of future tanning. | Low Risk |

| Gao et al., 2018 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | Male respondents of 2015 National Health Interview Survey | 370 SMM; 13,328 heterosexual men | • Indoor tanning bed use • Sunburns • Sunscreen use |

SMM use indoor tan and use sunless tanning more frequently than heterosexual men | Low Risk |

| Klimek et al., 2018 | 16–35 | Survey study | No | SMM in San Diego, California | 198 gay men, 25 bisexual men, 1 heterosexual man, 7 other sexual orientation | • Current and ideal skin tones • T anning behavior |

Darker ideal skin tone correlated with use of indoor tanning and intent to indoor tan among SMM | Moderate Risk |

| Mansh et al., 2015 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | 2001–2005 and 2009 California Health Interview Survey and 2013 National Health Interview Survey Respondents | 3,083 SMM; 78,487 heterosexual men; 3,029 SMW; 107,976 heterosexual women | • Indoor tanning bed use in past 12 months • History of physician- diagnosed skin cancer |

SMM have increased odds of history of skin cancer and indoor tanning bed use when compared to heterosexual men. SMW have lower odds of indoor tanning than heterosexual women. | Low Risk |

| Morrison et al., 2019 | ≥18 | Survey study | No | Venue- and time-based sample of respondents to 2017 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Survey | 495 MSM in San Francisco, San Mateo, and Marin counties of California | • Indoor tanning bed use in past 12 months | 7.5% prevalence of indoor tanning bed use among MSM. Binge drinking in past 30 days higher among indoor tanners. Reasons for tanning included improved attractiveness, mood elevation, and stress relief. | Moderate Risk |

| Nogg et al., 2019 | 15–35 | Survey study | No | SMM in San Diego, California | 290 SMM in San Diego, CA | • Indoor tanning dependence • Past indoor tanning behaviors • Intent to indoor tan • Sunscreen use |

Tanning dependence in SMM is associated with greater future intent to indoor tan | Moderate Risk |

| Rosario et al., 2016 | 9–25 | Prospective cohort study | Yes | Growing Up Today Study (1999–2010) respondents | 101 gay men; 24 bisexual men; 245 mostly heterosexual men; 3,427 heterosexual men; 80 lesbian women; 136 bisexual women; 961 mostly heterosexual women; 4,984 heterosexual women | • Indoor tanning booth use • Sunburn • Infrequent sunscreen use |

Gay men were more likely to frequently indoor tan than heterosexual men. Lesbian women used indoor tanning booths less frequently than heterosexual women. | Low Risk |

| Singer et al, 2020 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | 2014–2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Respondents | 7,516 gay men, 5,088 bisexual men, 351,468 heterosexual men; 5,392 lesbian or gay women, 9,445 bisexual women, 466,355 heterosexual women | • Lifetime skin cancer diagnosis | Both gay and bisexual men carry an increased lifetime prevalence of skin cancer compared to heterosexual men. Bisexual women have lower lifetime prevalence of skin cancer compared to heterosexual women. | Low Risk |

| Singer et al, 2020 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | 2014–2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Respondents | 1,214 transgender men, 1,675 transgender women, 766 Gender nonconforming individuals, 368,197 cisgender men, 492,345 cisgender women | • Lifetime skin cancer diagnosis | Gender-nonconforming individuals carry increased lifetime prevalence of skin cancer diagnosis compared to cisgender men. | Low Risk |

| Yeung et al., 2016 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | 2013 National Health Interview Survey Respondents | 320 gay men; 78 bisexual men; 14,495 heterosexual men; 251 lesbian women; 155 bisexual women; 18,051 heterosexual women | • Indoor tanning bed use | Gay and bisexual men were more likely to have ever indoor tanned or to frequently indoor tan | Low Risk |

| Yeung et al., 2019 | ≥18 | Cross-sectional study | Yes | Female respondents of 2015 National Health Interview Survey | 464 SMW; 17,340 heterosexual women | • Indoor tanning device use in past 12 months • ≥ 1 Sunburns in past 12 months • Skin cancer screening exam in past 12 months • Frequent sun- protective behaviors |

No difference between SMW and heterosexual women with regard to sunburn, indoor tanning device use, skin cancer screening, and sun protective behaviors. | Low Risk |

Abbreviations: SMM = sexual minority men; SMW = sexual minority women; MSM = men who have sex with men

No specific ages given, but all participants were enrolled in high school at time of data collection

Assessment performed using quality assessment checklist for studies assessing prevalence11

Skin Cancer Development among Sexual Minority Populations

A cross-sectional study using two separate national samples to compare the risk of skin cancer development in sexual minority populations relative to their heterosexual peers.12 Using data from the 2001–2005 California Health Interview Surveys, SMM were shown to have a significantly increased odds of lifetime history of any skin cancer (aOR: 1.6 [1.2–2.1]), melanoma (aOR: 1.7 [1.1 −2.7]), and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) (aOR: 1.4 [1.0–2.1]). Using the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, Mansh et al found that SMM had significantly higher odds of lifetime history of any skin cancer (aOR: 2.1 [1.1 −4.0]), though they were unable to assess specific subtypes of skin cancer in this sample. This study also found lower odds of NMSC in SMW compared to heterosexual women (aOR: 0.6 [0.4–0.9]), but no significant difference in lifetime history of any skin cancer or melanoma based on sexual orientation among women in either sample.

Another cross-sectional study using data from the 2014 to 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys examining lifetime skin cancer prevalence among sexual minority populations. In this study, the authors found that gay (aOR: 1.3 [1.1–1.5]) and bisexual (aOR: 1.5 [1.0–2.2]) men had increased lifetime prevalence of skin cancer compared to heterosexual men, and bisexual women (aOR: 0.8 [0.6–1.0]) had decreased lifetime prevalence of skin cancer compared to heterosexual women. There was no difference between heterosexual and gay or lesbian women with regard to lifetime skin cancer prevalence.

Skin Cancer Development among Gender Minority Populations

A cross-sectional study using data from the 2014 to 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys examining lifetime skin cancer prevalence among gender minority populations.14 The results showed that gender nonconforming individuals (aOR: 2.1 [1.0–4.4]) had significantly higher odds of lifetime skin cancer diagnosis compared to cisgender men, but no difference was found when comparing transgender men (aOR: 1.1 [0.7–1.9]) or transgender women (aOR: 1.2 [0.7–1.9]) with cisgender men.

History of Indoor Tanning Bed Use

Three cross-sectional studies of adults evaluated prevalence of indoor tanning bed use for SMM versus heterosexual men and identified a prevalence of 5.0–27.0% in SMM versus 1.6–9.1% in heterosexual men (OR range: 2.8–5.9, Table 2).12,15–17 The only study to sub-stratify gay men and bisexual men and found both groups were more likely to report ever having used an indoor tanning bed when compared to heterosexual men (Table 2).7

Table 2:

Prevalence and Odds Ratios of Skin Cancer Risk Behaviors by Sexual Orientation and Sex

| Lifetime Development of Any Skin Cancer | ||||||||||

| Male Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | Female Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| Article | Data Source | Variable | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual |

| Mansh et al, 2015 | 2009 California Health Interview Survey (n = 36,814) | Lifetime diagnosis of any skin cancer | - | - | 4.3% (1.6 [1.2–2.1]) | 2.7% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 2.3% (0.8 [0.6–1.2]) | 2.6% (10 [ref]) |

| 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 13,698) | Lifetime diagnosis of any skin cancer | - | - | 6.7% (2.1 [1.1–4.0]) | 3.2% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 1.6% (0.5 [0.1–2.0]) | 3.1% (10 [ref]) | |

| Singer et al, 2020 | 2014–2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey (n = 845,264) | Lifetime diagnosis of any skin cancer | 8.1% (1.3 [1.1–1.5]) | 8.4% (1.5 [1.0–2.2]) | - | 6.7% (10 [ref]) | 5.9% (1.0 [0.7–13]) | 4.7% (0.8 [0.6–1.0]) | - | 6.6% (10 [ref]) |

| Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use* | ||||||||||

| Male Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | Female Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| Article | Data Source | Variable | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual |

| Blashill, et al, 2014 | National Longitudinal Adolescent Health study, age 16 (n = 1,767) | Any indoor tanning bed use (ever)a | - | - | 27.0% (3.9 [1.6–9.8]) | 8.6% (1.0 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Gao et al., 2018 | 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 13,698) | Any indoor tanning bed use (ever)b | - | - | 22.1% (3.1 [2.1–4.6]) | 9.1% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Gao et al., 2018 | 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 13,698) | Any indoor tanning bed use (last 12 months)b | - | - | 6.6% (5.9 [3.5–9.8]) | 1.5% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Mansh et al., 2015 | 2009 California Health Interview Survey (n = 36,814) | Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 monthsc | - | - | 7.4% (5.8 [2.9–11.6] | 1.5% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 2.6% (0.4 [0.2–0.9]) | 5% (10 [ref]) |

| Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 months; Ages 18–34c | - | - | 11.1% (5.9 [2.1–17.0]) | 2.3% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 4.8% (0.5 [0.2–1.4]) | 7.5% (10 [ref]) | ||

| 2013 National Health Interview Survey (n = 33,350) | Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 monthsd | - | - | 5.1% (3.2 [1.8–5.6]) | 1.6% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 4.2% (0.5 [0.3–0.8)]) | 6.5% (10 [ref]) | |

| Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 months; Ages 18–34d | - | - | 10.6% (3.6 [1.5–8.4]) | 2.6% (10 [ref]) | - | - | 7.6% (0.4 [0.2–0.7]) | 12.2% (10 [ref]) | ||

| Yeung et al., 2016 | 2013 National Health Interview Survey (n = 34,557) | Any Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 monthse | 5.0% (2.8 [1.4–5.6]) | 7.1% (4.6 [1.6–13.2]) | - | 1.7% (10 [ref]) | 4.1% (0.5 [0.3–12]) | 6.1% (0.6 [0.3–1.3]) | - | 6.6% (10 [ref]) |

| Yeung et al., 2019 | 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 18,601) | Any Indoor Tanning Device Use in past 12 monthsf | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.6% (0.9 [0.5–1.5]) | 5.2% (10 [ref]) |

| Frequent Indoor Tanning Bed Use (10 or more uses in 12 months) | ||||||||||

| Male Sex Prevalence* (OR/aOR* [95% CI]) | Female Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| Article | Data Source | Variable | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexua |

| Rosario et al., 2016 | Growing Up Today Study (1999–2010) (n = 8,752) | Frequent Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 months (10 or more uses)g | 24% (4.7 [3.0–7.4]) | 8.3% (1.3 [0.4–4.9]) | - | 7.2% (10 [ref]) | 22.5% (0.4 [0.3–0.7]) | 21.3% (0.4 [0.3–0.6]) | - | 41.6% (10 [ref]) |

| Yeung et al., 2016 | 2013 National Health Interview Survey (n = 34,557) | Frequent Indoor Tanning Bed Use in Past 12 months (10 or more uses)e | 3.4% (4.7 [2.0–112]) | 4.5% (7.4 [2.1–26.4]) | - | 0.7% (10 [ref]) | 2.1% (0.5 [0.2–14]) | 4.5% (0.8 [0.3–2.0]) | - | 3.7% (10 [ref]) |

| Outdoor Sun Exposure | ||||||||||

| Male Sex Prevalence* (OR/aOR* [95% CI]) | Female Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| Article | Data Source | Variable | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexua |

| Blashill, et al., 2014 | National Longitudinal Adolescent Health study, age 16 (n = 1,767) | Frequent or occasional sunbathing to get a tan, age 16a | - | - | 22.3% (1.7 [0.7–4.3]) | 14.5% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Gao et al., 2018 | 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 13,698) | Sunburn in last 12 months (at least 1)b | - | - | 36.1% (1.0 [0.7–1.3]) | 35.1% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Rosario et al, 2016 | Growing Up Today Study (1999–2010) (n = 8,752) | Sun exposed sometimes, frequently, or always last summerg | 90.9% (0.9 [0.7–1.3]) | 91.3% (1.0 [0.5–2.0]) | - | 87.4% (10 [ref]) | 85.7% (1.0 [0.7–14]) | 76.5% (0.8 [0.6–1.0]) | - | 83.7% (10 [ref]) |

| Frequent Sunburns (5 or more times last summer)g | 17.8% (0.8 [0.5–1.3]) | 16.7% (0.6 [0.2–1.4]) | - | 22.1% (10 [ref]) | 25.0% (1.1 [0.7–19]) | 23.5% (1.1 [0.7–17]) | - | 25.3% (10 [ref]) | ||

| Yeung et al., 2019 | 2015 National Health Interview Survey (n = 18,601) | Sunburn (1 or more) in past 12 months | - | - | - | - | - | - | 43.3% (1.08 [0.8–1.5]) | 33.2% (10 [ref]) |

| Infrequent Sunscreen Use | ||||||||||

| Male Sex Prevalence* (OR/aOR* [95% CI]) | Female Sex Prevalence (OR/aOR [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| Article | Data Source | Variable | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual | Gay | Bisexual | Sexual Minority | Heterosexual |

| Blashill, et al., 2014 | National Longitudinal Adolescent Health study, age 16 (n = 1,767) | Unlikely to wear sunblock when outside for >1 hour, age 16a | - | - | 70.5% (0.9 [0.4–2.0]) | 73.5% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - |

| Unlikely to wear sunblock when outside for >1 hour, age 29a | - | - | 75.9% (1.0 [0.4–3.0]) | 75.2% (10 [ref]) | - | - | - | - | ||

| Rosario et al., 2016 | Growing Up Today Study (1999–2010) (n = 8,752) | Infrequent or seldom use of sunscreeng | 20.8% (1.3 [0.9–17]) | 8.3% (1.0 [0.8–1.3]) | - | 17.6% (10 [ref]) | 15.0% (1.1 [0.8–15]) | 9.6% (1.2 [0.6–2.3]) | - | 7.4% (10 [ref]) |

Prevalence and odds ratios are unadjusted

Age-adjusted prevalence rates standardized against the age distribution of adult men in the general population; odds ratios adjusted for age, race, region, educational level, body mass index, sun sensitivity, personal history of skin cancer, and family history of skin cancer

Age-adjusted prevalence rates standardized against the age distribution of adult men in the general population; odds ratios adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index, annual household income, health care use, smoking history, and current alcohol consumption

Age-adjusted prevalence rates standardized against the age distribution of adult men in the general population; odds ratios adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, region, body mass index, annual household income, health care use, smoking history, current alcohol consumption, and immunosuppression

Unadjusted prevalence rate; odds ratio adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, educational level, income level, health insurance status, geogprahic region, and personal history of any skin cancer

Unadjusted prevalence rate; odds ratio adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, income level, 116 smoking status, heavy alcohol use, and body mass index.

Unadjusted prevalence rate; odds ratio adjusted for age and race/ethnicity

Note: Blashill et al. (2017) reported on skin cancer risk among sexual minorities, however they only provided results stratified by race so the data could not be incorporated into this table.

A study examining indoor tanning bed use among SMM and heterosexual adolescents and found a significantly increased prevalence of tanning bed use among SMM (27.0%) compared to heterosexual adolescents (8.6%) (OR: 3.9).

Three studies have evaluated the prevalence of indoor tanning bed use among women by sexual minority status. One found a decreased likelihood of ever having indoor tanned among SMW compared to their heterosexual peers (OR: 0.4–0.6) (Table 2).12 The other two studies showed no difference between SMW and heterosexual women with regards to indoor tanning bed use.16,19

One study assessed indoor tanning risk among high school-aged participants by using the 2015 Youth Behavior Risk Survey in the only study able to stratify their sample by race in addition to sex and sexual orientation. In this study, among black participants, both sexual minority status (OR: 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5–8.0) and male sex (OR: 2.6 [1.0–6.6]) independently conferred increased risk of indoor tanning bed use, while in Hispanic participants sexual minority status conferred increased risk of tanning bed use for both men and women (OR: 3.9 [1.8–8.6]. Among white participants, sexual minority status was a risk factor for indoor tanning bed use among males (OR: 3.2; 95% CI, 1.3–7.7), but it decreased risk among females (OR: 0.4; 0.2–0.7).20

Frequent Indoor Tanning Bed Use

Two studies assessed frequent indoor tanning bed use (defined as 10 or more uses in the past 12 months) by sexual orientation among men and found a prevalence of 3.4–24% among gay men, 4.5–8.3% among bisexual men, and 0.7%−7.2% among heterosexual men.15,16 One study found significantly increased odds of frequent indoor tanning among gay men (aOR: 4.7 [2.0–11.2]) and bisexual men (aOR: 7.4 [2.1–26.4]) when compared to heterosexual men, but the other only found increased odds among gay men (aOR: 4.7 [3.0–7.4]).

Of two studies that assessed frequent use of indoor tanning beds among SMW, one found no statistically significant difference between gay (aOR: 0.5 [0.2–1.4]) or bisexual women (aOR: 0.8 [0.3–2.0]) compared to heterosexual women,16 while the other found significantly decreased odds of frequent indoor tanning among both gay (aOR: 0.4 [0.3–0.7]) and bisexual women (aOR: 0.4 [0.3–0.6]) compared to their heterosexual peers.15

Outdoor Sun Exposure and Infrequent Sunscreen Use

Four cross-sectional studies of adults examined outdoor UV exposure among sexual minorities compared to their heterosexual peers.15,17,19 While each of the three studies examined different variables related to sun exposure (frequent or occasional sunbathing to get a tan,20 1 or more sunburn in last 12 months,17,19 sun exposed sometimes, frequently, or always last summer, and >5 sunburns last summer15), none found an increased prevalence of high risk outdoor UV exposure among sexual minority men or women compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Table 2).

Both studies examining sunscreen use among sexual minority populations, found that prevalence of infrequent sunscreen use (self-reported history of “infrequent or seldom use of sunscreen” or being “unlikely to wear sunblock when outside for >1 hour”) was similar between sexual minority and heterosexual populations (Table 2).15,17

Motivations for Indoor Tanning among SMM

Four studies assessed motivations for indoor tanning among SMM. A Northern California survey of 495 SMM found that 37 (7.5%) reported current indoor tanning bed use. The majority of SMM surveyed understood that indoor tanning bed use increases risk of skin cancer, as only 10.8% disagreed that indoor tanning bed use increased skin cancer risk.21 Among indoor tanners, most common motivations included increased attractiveness (56.8%), mood elevation (32.4%), and stress relief (27.0%). Interestingly, 21 (56.8%) indoor tanners felt indoor tanning bed use prior to a sunny vacation would protect the skin.

A focus group study revealed that sexual minority men identified both aesthetic concerns and community pressures as reasons for wanting to initiate indoor tanning.22 SMM reported that tanned skin appeared healthier and more toned, which was appealing for the participants in this group. This study also found that fears of more rapid skin aging and increased risk of skin cancer were among the primary motivators for stopping indoor tanning among SMM.

Another survey study that showed that SMM who reported darker ideal skin tones were more likely to engage in both indoor and outdoor tanning, particularly among those were had a fairer skin type.23 A study examining biopsychosocial correlates of indoor tanning among SMM and found that perceived susceptibility to skin cancer was associated with decreased intent to indoor tan, while increased sociocultural pressures to tan were linked to higher intent to indoor tan.24 Finally, another study showed that SMM with higher levels of tanning dependence were more likely to engage in skin cancer risk behaviors, including indoor tanning, outdoor tanning, and less sunscreen use.23

Discussion

The results of this systematic review show that there are differences in prevalence of skin cancer and behaviors that increase risk of skin cancer among sexual and gender minorities, particularly with regard to ‘SMM. SMM have increased risk of skin cancer prevalence and disproportionately engage in use of indoor tanning beds. The single study that provided data on photoprotective behaviors of women suggests that while SMW may have a slightly increased risk of sunburns, SMW use tanning beds less frequently than heterosexual women and do not have an elevated risk of lifetime history of skin cancer.

Increased odds of skin cancer development among SMM likely reflects increased indoor UV exposure in this population. In our review, we found that SMM had between 3.0 and 6.0-fold increased odds of reporting a history of ever using an indoor tanning bed, and SMM also reported a higher prevalence of frequent indoor tanning bed use (>10 uses in past 12 months). Indoor UV exposure is strongly linked to both melanoma and keratinocyte carcinoma development,5,6,25 so this behavior is a possible explanation for the increased lifetime prevalence of skin cancer that has been shown in SMM. It is important to acknowledge that SMW utilize healthcare less than their heterosexual peers, which could result in fewer skin cancer diagnoses.26

Prior studies have shown that individuals who use indoor tanning beds are more likely to participate in outdoor tanning behaviors,24 but we found that there were no significant differences in history of sunbathing, sunburns, or infrequent sunscreen use by sexual orientation among men or women. This indicates that differences in sun-protective behavior are likely not a contributing factor in the increased prevalence of skin cancer among SMM, though further studies are required to determine if prevalence of intentional outdoor tanning is influenced by sexual minority status.

Smoking increases the risk of NMSC30 and tobacco use is more prevalent among sexual minorities,31,32 but the models of skin cancer risk included in our study found an increased risk of skin cancer among SMM even when controlling for smoking status. Immunosuppression and HIV infection also increase the risk of both melanoma and NMSC,33,34, and sexual minority men in the United States are disproportionately affected by HIV.35 One study found increased risk of skin cancer among SMM controlling for immunosuppression, while two studies have shown that skin cancer risk is higher among HIV-positive sexual minority men when compared to other HIV-positive individuals.34,36

Motivations for indoor tanning in the general population include relaxation, increased attractiveness, mood regulation, and peer influence,37,38 and our study shows that the motivations among SMM appear to be similar. The increased risk of tanning bed use in this population may indicate differential perceptions regarding ideal skin tone between sexual minority and heterosexual men, which is also evidenced by increased use of self-applied sunless tanning products or spray tans among SMM.17

Our review has important implications for future work to reduce disparities in skin cancer development and indoor tanning bed use for sexual minorities. First, providers and the larger medical community should be aware of the increased utilization of indoor tanning beds among SMM. Providers should also consider engaging in conversations around healthier alternatives to indoor UV exposure for achieving a tan, such as sunless tanning, as this has proven effective in decreasing indoor tanning bed use among women.39 Community outreach regarding the potential health risks of indoor tanning could provide beneficial, particularly if they focused on areas noted by SMM to be motivators to stop indoor tanning, such as skin cancer risk and accelerated skin ageing. Finally, only one included study examined lifetime skin cancer prevalence among transgender and gender-nonconforming populations, and no studies have yet examined skin cancer risk behaviors in this population. Further research is necessary to ultimately characterizing risk patterns affecting this population.

This systematic review must be considered in the context its limitations. First, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis because many of the included studies reported odds ratios that were adjusted using different covariates. All the included data is from cross-sectional studies, and therefore definitive conclusions regarding temporality cannot be established. Additionally, the studies included relied on self-reported history of skin cancer, indoor tanning bed use, and outdoor sun exposure that was not validated. Reliability and validity of self-reported diagnoses is controversial, with some studies showing self-reported skin cancer rates are lower than actual prevalence.40,41 Additionally, only one study accounted for HIV/immunosuppression status, so the link between immunosuppression status and skin cancer development in sexual minority populations is unclear. Finally, the studies in our review that assessed motivations for indoor tanning among SMM were all qualitative, so future quantitative studies are needed to validate these results in a generalizable manner.

Conclusion

Sexual minority men have a higher prevalence of both skin cancer and indoor tanning bed use compared to heterosexual men, which is likely due to unique community pressures and appearance ideals that face this community. A combination of outreach, education, and public health initiatives targeted at reducing indoor tanning bed use among SMM may reduce the elevated risk of skin cancer currently seen in this population.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and Costs of Skin Cancer Treatment in the US, 2002– 2006 and 2007– 2011. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;48(2):183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: I. Basal cell carcinoma. Archives of dermatology.1995; 131 (2): 157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentation factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: II. Squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of dermatology. 1995;131(2): 164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. European journal of cancer. 2005;41(1):45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren M-M, Han J, Qureshi AA, Linos E. Indoor tanning and nonmelanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2012;345:e5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colantonio S, Bracken MB, Beecker J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American academy of dermatology. 2014;70(5):847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhalter JE, Margolies L, Sigurdsson HO, et al. The national LGBT cancer action plan: a white paper of the 2014 National Summit on Cancer in the LGBT Communities. LGBT health. 2016;3(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behavioral Medicine. 2012;38(3):74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison MA, Morrison TG, Sager C-L. Does body satisfaction differ between gay men and lesbian women and heterosexual men and women?: A meta-analytic review. Body image. 2004;1(2):127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151 (4): 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2012;65(9):934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, Chren M-M, Arron S. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA dermatology. 2015;151(12):1308–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer S, Tkachenko E, Hartman R, Mostaghimi A. Association Between Sexual Orientation and Lifetime Prevalence of Skin Cancer in the United States. JAMA dermatology. February 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer S, Tkachenko E, Hartman R, Mostaghimi A. Gender Identity and Lifetime Prevalence of Skin Cancer in the United States JAMA dermatology. February 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosario M, Li F, Wypij D, et al. Disparities by sexual orientation in frequent engagement in cancer-related risk behaviors: a 12-year follow-up. American journal of public health. 2016;106(4):698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung H, Chen SC. Sexual orientation and indoor tanning device use: a population-based study. JAMA dermatology. 2016;152(1):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Y, Arron ST, Linos E, Polcari I, Mansh MD. Indoor Tanning, Sunless Tanning, and Sun-Protection Behaviors Among Sexual Minority Men. JAMA dermatology. 2018;154(4):477–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blashill AJ, Safren SA. Skin cancer risk behaviors among US men: the role of sexual orientation. American journal of public health. 2014;104(9):1640–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeung H, Baranowski ML, Chen SC. Skin cancer risk factors and screening among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blashill AJ. Indoor tanning and skin cancer risk among diverse US youth: Results from a national sample. JAMA dermatology. 2017;153(3):344–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison L, Raymond HF, Katz KA, et al. Knowledge, Motivations, and Practices Regarding Indoor Tanning Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in the San Francisco Bay Area. JAMA dermatology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Admassu N, Pimentel M, Halley M, et al. Motivations Among Sexual □ Minority Men for Starting and Stopping Indoor Tanning. British Journal of Dermatology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klimek P, Lamb KM, Nogg KA, Rooney BM, Blashill AJ. Current and ideal skin tone: Associations with tanning behavior among sexual minority men. Body image. 2018;25:31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blashill AJ, Rooney BM, Wells KJ. An integrated model of skin cancer risk in sexual minority males. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2018;41(1):99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, Gandini S. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2012;345:e4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blosnich JR, Farmer GW, Lee JG, Silenzio VM, Bowen DJ. Health inequalities among sexual minority adults: evidence from ten US states, 2010. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;46(4):337–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lostritto K, Ferrucci LM, Cartmel B, et al. Lifetime history of indoor tanning in young people: a retrospective assessment of initiation, persistence, and correlates. BMC public health. 2012;12(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckman CJ, Coups EJ, Manne SL. Prevalence and correlates of indoor tanning among US adults. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;58(5):769–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer AH, Wang TS, Yenokyan G, Kang S, Chien AL. Association of indoor tanning frequency with risky sun protection practices and skin cancer screening. JAMA dermatology. 2017;153(2):168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardi-Bee J, Ellison T, Bath-Hextall F. Smoking and the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of dermatology. 2012;148(8):939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe SE, Matthews AK, Lee JG, Veliz P, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ. Tobacco use and sexual orientation in a national cross-sectional study: age, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity–attraction differences. American journal of preventive medicine. 2018;54(6):736–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Haardorfer R, Vu M, Windle M, Berg CJ. Sex and sexual orientation in relation to tobacco use among young adult college students in the US: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2018;18(1):1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen CM, Knight LL, Green AC. Risk of melanoma in people with HIV/AIDS in the pre- and post-HAART eras: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, Quesenberry CP Jr, Engels EA, Asgari MM. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(5):350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Jama. 2008;300(5):520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanoy E, Dores GM, Madeleine MM, Toro JR, Fraumeni JF, Engels EA. Epidemiology of non-keratinocytic skin cancers among persons with AIDS in the United States. Infectious agents and cancer. 2009;4(S2):O10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider S, Diehl K, Bock C, et al. Sunbed use, user characteristics, and motivations for tanning: results from the German population-based SUN-Study 2012. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(1):43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gambla WC, Fernandez AM, Gassman NR, Tan MC, Daniel CL. College tanning behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and intentions: A systematic review of the literature. Preventive medicine. 2017;105:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski J, Bodenlos JS, Ma Y. The sunless study: a beach randomized trial of a skin cancer prevention intervention promoting sunless tanning. Archives of dermatology. 2010;146(9):979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desai MM, Bruce ML, Desai RA, Druss BG. Validity of self-reported cancer history: a comparison of health interview data and cancer registry records. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001; 153(3):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ming ME, Levy RM, Hoffstad OJ, Filip J, Gimotty PA, Margolis DJ. Validity of patient self-reported history of skin cancer. Archives of dermatology. 2004;140(6):730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]