Abstract

Objective:

To improve surgical pain control through cryoablation of intercostal nerves and reduce narcotic usage in patients undergoing open thoracic or thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAA or TAAA) repair.

Methods:

From 2012-2018, 117 patients underwent open repair of TAA or TAAA. Of those patients, 25(21%) received cryoablation (2016-2018) of their intercostal nerves and 92(79%) did not (2012-2018). The primary outcome was pain scores and narcotic usage from extubation day 1 to 10 or the day of discharge.

Results:

The median age (57 years), demographics, and preoperative comorbidities were not significantly different between the two groups. The cryoablation group had significantly more incidences of thoracoabdominal incisions (52% vs. 28%), urgent operations (32 % vs. 11%), and longer duration of chest tubes compared to the non-cryoablation group (all p<0.05). T9-T12 intercostal arteries were selectively reimplanted. Left intercostal nerves were cryoablated from T3-T9 if two thoracotomies were used; or two intercostal spaces above and below the thoracotomy if one thoracotomy was used. There were no significant differences between the non-cryoablation and cryoablation groups in postoperative stroke, paraplegia (5%), pneumonia, and in-hospital mortality (0.9%). However, the average usage of narcotics was significantly reduced in the cryoablation group by 28 MME(equal to four 5 mg Oxycodone)/patient/day in ten days after extubation, p=0.005.

Conclusion:

With cryoablation of intercostal nerves, the postoperative surgical pain was well controlled and narcotic usage was significantly decreased after TAA or TAAA repair. Cryoablation of intercostal nerves was a safe and effective measure for postoperative pain control in TAA or TAAA repair.

Keywords: Postoperative Pain Management, Postoperative Narcotic Usage, Intercostal Nerve Cryoablation, TAA, TAAA

INTRODUCTION

Thoracotomy incisions are painful incisions, which can lead to postoperative complications as a result of inadequate pain control. Postoperative respiratory function optimization is very important but can be limited in patients with poor pain control, resulting in respiratory failure and pneumonia.1 Multiple different analgesic methods have been tried for post-thoracotomy pain relief, each with their own benefits and side effects.2 Common analgesic methods have included narcotic pain medications, epidural analgesia, intercostal nerve block, local anesthetic infusion, and cryoablation of intercostal nerves.2

Extensive thoracotomy or thoracoabdominal incisions have been used for open thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) or thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair. Postoperative pain control has always been an important issue that can hurdle the recovery of the patients and prolong their hospital stay. Studies have demonstrated the benefit of cryoanalgeisa for postoperative pain relief in thoracotomies for general thoracic procedures without serious adverse events.3–6 Others have demonstrated no significant difference or worse pain relief and increased postoperative neuralgia when comparing cryoablation to other methods.6, 7 Cryoablation has not been reported to be used in TAA or TAAA repair for postoperative pain control. The big fear of using cryoablation of intercostal nerves is the uncertainty of direct thermal injury to the spinal cord by cryoablation and subsequent paraplegia.

In this study, we examined the postoperative outcomes, pain scores, and narcotic usage 10 days after extubation or to discharge date between patients who did or did not undergo cryoablation for thoracotomy or thoracoabdominal incision in the setting of TAA or TAAA repair. We hypothesize that the cryoablation group will have better pain control and lower narcotic usage postoperatively compared to the non-cryoablation group.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00140040; March 9, 2018) and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Patient Selection

From the years 2012-2018, 117 patients underwent open surgical repair of TAA or TAAA. Of these 117 patients, 25 (21%) received cryoablation of their intercostal nerves and 92 (79%) did not based on surgeons’ practice. Cryoablation of intercostal nerves was performed from February 2016 - June 2018, and the operations without cryoablation were performed from January 2012 - May 2018. During the cryoablation period, 24 patients in the non-cryoablation group were not treated with cryoablation, while 25 were treated with cryoablation in the cryoablation group. The postoperative pain was managed with narcotics and non-narcotic medication (Toradol) by the ICU intensivists. This management of postoperative pain after TAA or TAAA repair was not changed throughout the study period and was the same between the cryoablation and non-cryoablation groups. Our nursing staff recorded pain scores as standard protocol for all patients undergoing cardiac surgery. There was no epidural analgesia, intercostal nerve block or other pain management used during the study period.

Data Collection

Investigators retrospectively obtained data elements from the Society of Thoracic Surgery from Michigan Medicine’s Cardiac Surgery Data Warehouse to determine pre-, intra-, and postoperative characteristics. Data collection was supplemented through a review of medical records and operative reports. Primary outcomes were defined as pain scores and narcotic usage from extubation to post-extubation day ten or day of discharge. Patient pain score data were obtained through medical record review and based on a 0-10 scale, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the highest level of pain. The pain score was the overall pain of the thoracic or thoracoabdominal incision. Non-numerical pain data was not included. Pain data was reported as the average pain score per day for each patient. The patient’s postoperative narcotic use was obtained through medical record review and calculated as total measured morphine equivalents (MME)8 per day. The patient’s postoperative Toradol use was obtained through medical record review as well. Survival data were obtained through the National Death Index database through December 31st, 2018 9 and supplemented with medical record review.

Operative Technique

TAA or TAAA was performed through one skin incision as a left posterior lateral incision for TAA repair and with extension to the abdomen as a paramedian incision for TAAA repair. Right thoracotomy was used for the right side descending thoracic aortic aneurysm. For most TAAs, we used one skin incision with two separate thoracotomies in the 4th and 7th or 8th intercostal spaces to replace the distal arch and the whole descending thoracic aorta. For TAAAs, we used one skin incision and either a thoracotomy in the 5th intercostal space with a division of the costal margin or two thoracotomies in the 4th and 8th intercostal spaces with an extension of 8th thoracotomy across the costal margin to the abdominal incision. Every patient had a lumbar drain placed before incision. Distal perfusion was achieved through the left femoral artery, iliac artery, or distal non-aneurysmal aorta when the proximal aorta was clamped for anastomosis. Depending on where the aneurysm was, the proximal anastomosis was completed with clamping between the left common carotid artery and left subclavian artery or distal to the left subclavian artery. If the aortic arch was aneurysmal, or patients’ TAA or TAAA was due to chronic dissection, hypothermic circulatory arrest was used for open proximal aortic anastomosis with a bladder temperature of 18 °C. T9-12 intercostal arteries were reimplanted routinely if they were patent as patches or with an 8 or 10 mm side branch Dacron graft. The TAAA was replaced with a multi-branch TAAA Dacron graft (hemashield, Maquet; Gelweave, Terumo). The celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and left and right renal arteries were reimplanted/replaced with a side branch graft individually. Distal aortic anastomosis was at the non-aneurysmal aorta. If the whole aorta and common iliac arteries are involved, then we replaced the whole aorta and iliac arteries.

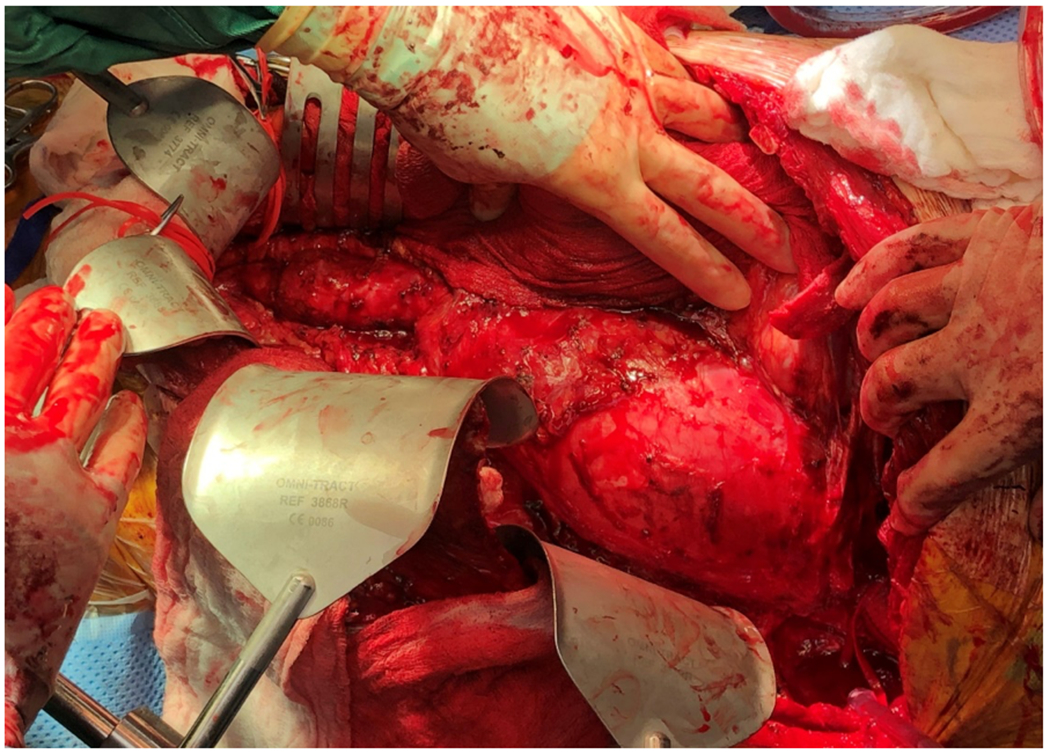

Cryoablation of intercostal nerves was performed after the repair (Figure 1, Video), during rewarming. The cryoablation probe was used off-label as it was not used for atrial fibrillation. There was not any conflict of interest. We ablated 3rd to 9th intercostal nerves if two thoracotomies in the 4th and 7th/8th intercostal spaces were used. We ablated two intercostal nerves above and below if one thoracotomy was used, for example, 3rd to 7th intercostal nerves if only one thoracotomy in the 5th intercostal space was used, and 5th or 6th to 9th intercostal nerves if only one thoracotomy in the 7th or 8th intercostal space was used. We did not ablate the T10 intercostal nerve for any patients to avoid loss of sensation of a large area of the abdominal wall. We placed the cryoICE cryoablation probe (AtriCure, Mason, OH) directly to the intact pleura 5 cm lateral to the costovertebral joint and below the lower edge of the upper rib with a temperature of −60 °C for 2 minutes for each intercostal nerve. Ablation was performed here because it was easy to see and perform, and it was far enough from the spinal cord not to cause direct thermal injury to the spinal cord. If a rib was shingled, the nerve-vascular bundle was ligated and divided, and we would not apply the cryoablation for that intercostal nerve.

Figure 1:

A sample patient with chronic type B aortic dissection and a large thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) underwent open repair and intercostal nerve cryoablation. The patient was extubated within 12 hours after surgery, complained of NO incisional pain at all, and was out of bed and walking on postoperative day 1. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6 without any prescription for narcotics and felt numbness of his left chest wall and abdominal wall along the incision. A: Intraoperative photo of the TAAA, B: Replacement of TAAA with 28 mm Dacron graft and reimplantation of the left renal artery, celiac artery, and T10 intercostal artery. C: An example of cryoablation of T9 intercostal nerves in a different patient with open TAAA repair.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as median (interquartile range, 25%, 75%) for continuous data, and n (%) for categorical data. Univariate comparisons between cryoablation and non-cryoablation groups were performed using chi-square tests for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous data. Kolmogorov-Smirnov D test and Cramer-von Mises tests were used to test the normality of the data, which revealed the non-normal distribution of the data. Therefore, we used conservative non-parametric tests for group comparisons for continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival curves with the log-rank test for all patients. A mixed model analysis was used to analyze the longitudinal relationship between pain score or narcotic usage and covariates (cryoablation vs. non-cryoablation, days post-extubation, age, gender, TAA vs. TAAA, one thoracotomy vs. two thoracotomies) in both groups as fixed effects. Patients were modelled as the random intercept and autoregression were used as the covariance matrix to take the correlation over time within patients into account. Time and treatment interaction was taken into account in these models and were insignificant.

RESULTS

Demographic and Preoperative Data

The patients in both groups had similar median age and no significant difference in gender. All pre-existing comorbidities were similar, including coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes, dialysis, hypertension, cerebral vascular accident (CVA), congestive heart failure (CHF), arrhythmia, liver disease, Marfan syndrome, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) function class. There were also no significant differences in bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), aortic insufficiency, or aortic stenosis. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre-operative & Demographic Data

| Variable | Total (n=117) | Non-Cryoablation (n=92) | Cryoablation (n=25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 57 (50, 64) | 57 (50, 63) | 60 (51, 67) | 0.2 |

| Sex (Female) | 31 (26) | 28 (30) | 3 (12) | 0.06 |

| Pre-existing Comorbidities | ||||

| CAD | 11 (9.4) | 8 (8.7) | 3 (12) | 0.62 |

| Diabetes | 11 (9.4) | 9 (9.8) | 2 (8) | 0.79 |

| Dialysis | 3 (2.6) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (4) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension | 106 (91) | 83 (90) | 23 (92) | 1.0 |

| CVA | 13 (11) | 12 (13) | 1 (4) | 0.29 |

| CHF | 20 (17) | 14 (15) | 6 (24) | 0.37 |

| Arrhythmia | 17 (15) | 14 (15) | 3 (12) | 1.0 |

| Liver Disease | 5 (4.3) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (8) | 0.29 |

| MFS | 12 (10) | 11 (12) | 1 (4) | 0.46 |

| Aortic Insufficiency | 0.79 | |||

| None | 49 (42) | 38 (41) | 11 (44) | |

| Trivial/Trace/Minimal | 32 (27) | 24 (26) | 8 (32) | |

| Mild | 31 (26) | 25 (27) | 6 (24) | |

| Moderate | 5 (4.3) | 5 (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Aortic Stenosis | 6 (5.1) | 6 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| BAV | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0.21 |

| Lung Disease | 0.13 | |||

| None | 86 (74) | 67 (73) | 19 (76) | 0.75 |

| Mild | 16 (14) | 14 (15) | 2 (8) | 0.35 |

| Moderate | 12 (10) | 8 (8.7) | 4 (16) | 0.29 |

| Severe | 3 (2.6) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Tobacco Use | 0.23 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 38 (32) | 31 (34) | 7 (28) | 0.60 |

| Former Smoker | 58 (50) | 43 (47) | 15 (60) | 0.24 |

| Current Smoker | 21 (18) | 18 (20) | 3 (12) | 0.38 |

| Alcohol | 0.36 | |||

| None | 73 (62) | 55 (60) | 18 (72) | 0.26 |

| <1 drink/week | 24 (21) | 22 (24) | 2 (8) | 0.08 |

| 2-7 drinks/week | 12 (10) | 9 (10) | 3 (12) | 0.75 |

| >8 drinks/week | 8 (6.8) | 6 (6) | 2 (8) | 0.79 |

| Previous Cardiac Surgery | ||||

| CABG | 10 (8.5) | 8 (8.7) | 2 (0) | 1.0 |

| Valve Surgery on Any Valve | 44 (38) | 35 (38) | 9 (36) | 0.85 |

| Aortic Root Replacement/Repair | 14 (12) | 9 (9.8) | 5 (20) | 0.17 |

| Ascending Aorta Replacement/Repair | 34 (29) | 26 (28) | 8 (32) | 0.72 |

| Aortic Arch Replacement/ Repair | 31 (26) | 24 (26) | 7 (28) | 0.85 |

| Descending Aorta Replacement/Repair | 16 (14) | 12 (13) | 4 (16) | 0.74 |

Data presented as median (25 %, 75 %) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MFS, Marfan syndrome; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Intra-Operative Data

The cryoablation group had significantly more urgent statuses, aortic arch aneurysms and aortic arch replacement, type I thoracoabdominal aneurysms, and extensive incision (thoracoabdominal incisions: 52% vs. 28%). The utilization of thoracotomies (one vs. two thoracotomies) and hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA), HCA and cardiopulmonary bypass time, and intraoperative packed red blood cells transfusion were similar between the two groups. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intra-Operative Data

| Variable | Total (n=117) | Non-Cryoablation (n=92) | Cryoablation (n=25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 0.83 | |||

| First Cardiovascular Surgery | 30 (26) | 25 (27) | 5 (20) | 0.47 |

| First Re-op Cardiovascular Surgery | 53 (45) | 39 (42) | 14 (56) | 0.22 |

| Second Re-op Cardiovascular Surgery | 27 (23) | 22 (24) | 5 (20) | 0.68 |

| Third or More Re-op Cardiovascular Surgery | 7 (6) | 6 (6.5) | 1(4) | 1.0 |

| Status | 0.03 | |||

| Elective | 98 (84) | 81 (88) | 17 (68) | 0.02 |

| Urgent | 18 (15) | 10 (11) | 8 (32) | 0.01 |

| Emergent | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Indications for operation | ||||

| Acute Aortic Dissection | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Aortic Rupture | 3 (2.6) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm | 57 (49) | 46 (50) | 11 (44) | 0.59 |

| Thoracoabdominal Aneurysm | 56 (48) | 43 (47) | 13 (52) | 0.64 |

| I | 6 (5.1) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (16) | 0.02 |

| II | 24 (21) | 18 (20) | 6 (24) | 0.63 |

| III | 5 (4.2) | 5 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 0.06 |

| IV | 6 (5.1) | 6 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 0.34 |

| V | 7 (6) | 5 (5.4) | 2 (8) | 0.64 |

| Unknown | 8 (6.8) | 7 (7.6) | 1 (4.0) | 0.53 |

| Thoracotomy Incision Type | 0.006 | |||

| Left | 75 (64) | 65 (71) | 10 (40) | 0.005 |

| Right | 3 (2.6) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (8) | 0.11 |

| Thoracoabdominal | 39 (33) | 26 (28) | 13 (52) | 0.03 |

| One Thoracotomy | 35 (30) | 27 (29) | 8 (32) | 0.80 |

| Two Thoracotomies | 82 (70) | 65 (71) | 17 (68) | 0.80 |

| HCA (%) | 63 (54) | 49 (53) | 14 (56) | 0.81 |

| Circulatory Arrest Time (minutes) | 31 (24, 39) | 33 (26, 39) | 25 (19, 31) | 0.05 |

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass Time (minutes) | 228 (188, 263) | 229 (189, 262) | 221 (178, 302) | 0.75 |

| Red Blood Cell (units) | 2 (0, 4) | 1.5 (0, 4) | 3 (0, 3) | 0.85 |

Data presented as median (25 %, 75 %) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

The aortic ruptures were complications of one acute aortic dissection, one thoracic aortic aneurysm, and one thoracoabdominal aneurysm of unknown extent.

Perioperative Outcomes

The perioperative outcomes were very similar between cryoablation and non-cryoablation groups, including hours of intubation, hours in the intensive care unit (ICU), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, pneumonia, sepsis, permanent paralysis (4% vs. 5.4%), new-onset renal failure, intra-operative mortality (0% vs. 0%), in-hospital mortality (0% vs. 1%), and 30-day mortality (4% vs. 1.2%). The cryoablation group had a significantly longer chest tube duration (9.6 vs. 6.6 days) and length of stay (15 vs. 11 days) compared to the non-cryoablation group. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative Outcomes

| Variable | Total (n=117) | Non-Cryoablation (n=92) | Cryoablation (n=25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours Intubated | 19 (11,38) | 18 (11, 37) | 28 (12, 55) | 0.32 |

| Prolonged Ventilation | 41 (35) | 29 (31.5) | 12 (48) | 0.13 |

| ICU Stay (Hours) | 122 (95,190) | 119 (95, 188) | 141 (95, 234) | 0.37 |

| ICU Readmission | 5 (4.2) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (4) | 0.94 |

| Length of Stay (days) | 13 (9,18) | 11 (8,17) | 15 (10,19) | 0.03 |

| Reoperation for Bleeding/Tamponade | 5 (4.2) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (4) | 1.0 |

| Pneumonia | 13 (11) | 9 (9.8) | 4 (16) | 0.47 |

| Chest Tube Removal (Days) | 7.5 (5.4,9.6) | 6.6 (4.7,8.8) | 9.6 (7.4,15) | 0.0003 |

| Sepsis | 5 (4.2) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (8) | 0.29 |

| MI | 3 (2.6) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Stroke | 3 (2.6) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (4) | 0.52 |

| TIA | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0.04 |

| Permanent Paralysis | 6 (5.1) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (4) | 0.77 |

| Transient Paralysis | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| New Onset Renal Failure | 8 (6.8) | 7 (7.6) | 1 (4) | 1.0 |

| Permanent Pacemaker/ICD | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 23 (20) | 18 (20) | 5 (20) | 1.0 |

| Intra-operative Mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| In Hospital Mortality | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| 30 Day Mortality | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (4) | 0.38 |

Data presented as median (25 %, 75 %) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MI, myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

The cryoablation group, on average, reported 0.5 points less pain score each day than the non-cryoablation group, over 10 days post-extubation or to discharge, when adjusted for covariates (p=0.16). (Figure 2A, Table 4, Supplemental Table 1). The cryoablation group consumed on average 28 MME (equal to four 5mg Oxycodone) per patient per day fewer narcotics than the non-cryoablation group, over time, when adjusted for covariates (p=0.005). (Figure 2B, Table 4, Supplemental Table 2). The total narcotic usage per day per patient in the cryoablation group was 60% of that in the non-cryoablation group on post-extubation day 1 and decreased to 20% on post-extubation day 10. (Figure 2B, Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 2:

Longitudinal analysis of pain score and narcotic consumption over time in cryoablation vs. non-cryoablation groups. A: Average pain score per patient for each day from post-extubation day 1 to day 10 or discharge for the cryoablation group and non-cryoablation group. Pain scores were measured on a 0-10 scale, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain. The cryoablation group had, on average, over time, 0.5 points less pain score (p=0.16) than the non-cryoablation group when adjusting for age, gender, one vs. two thoracotomies, and thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) vs. thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA). B: Average total narcotic usage per patient each day from post-extubation day 1 to day 10 or discharge for the cryoablation group and non-cryoablation group. Since multiple narcotics were used, measured morphine equivalents (MME) were used to measure total narcotic usage each day. The cryoablation group used on average, over time, 28 MME (equal to four 5 mg Oxycodone) per day per patient less narcotics (p=0.005) than the non-cryoablation group when adjusting for age, gender, one vs. two thoracotomies, and thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) vs. thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA).

Table 4:

The risk factors for pain score and narcotic usage by Mixed Model Analysis.

| Variable | Pain Score Difference | P-Value | Narcotic Usage Difference (MME) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryoablation vs. non-cryoablation | −0.5 (0.4) | 0.16 | −28 (9.6) | 0.005 |

| Days post-extubation | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.30 | 1.2 (0.8) | 0.12 |

| Age (per year) | −0.06 (0.01) | <.0001 | −0.84 (0.3) | 0.01 |

| Male vs. Female | 0.16 (0.3) | 0.63 | −0.17 (9) | 0.99 |

| One vs. two Thoracotomies | 0.29 (0.3) | 0.34 | 9.6 (9) | 0.29 |

| TAA vs. TAAA | 0.01 (0.3) | 0.97 | −11 (8) | 0.19 |

Mixed model analysis was used given the unbalanced data structure. This mixed model modeled the repeated measurements of pain score as the outcome with cryoablation vs. non-cryoablation, days post-extubation, time, age, gender, one thoracotomy vs. two thoracotomies, and thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) vs. thoracoabdominal aneurysm (TAAA). Data were presented as mean (standard error). Briefly, for pain scale over time, the cryoablation group had, on average, 0.5 (p=0.16) points less on pain scale than the non-cryoablation group. There was no significant interaction between the groups and time (p=0.30). The same method was used for narcotic usage. Over time, the cryoablation group had an average of 28 measured morphine equivalents (MME) (equal to four 5 mg Oxycodone) per day per patient less narcotic usage than the non-cryoablation group. There was no significant interaction between the groups and time (p=0.12).

Mid-term outcome

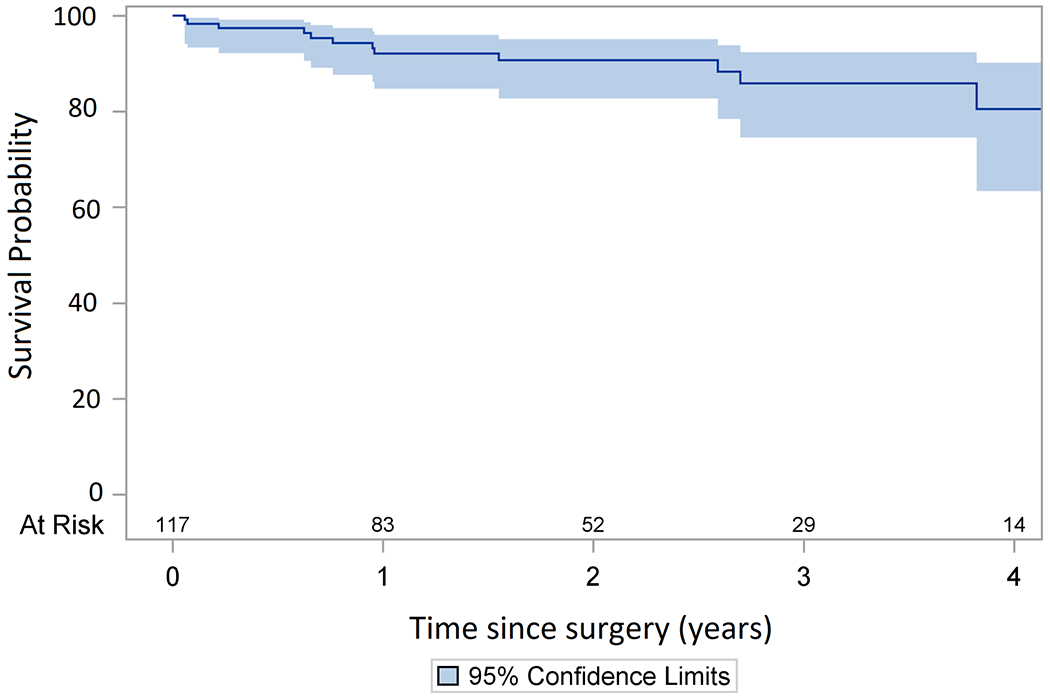

The follow-up time was 3.6 ± 1.9 years with 90% follow-up completeness. Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored to the date of the last known status. There was no significant difference in mid-term survival between the cryoablation and non-cryoablation groups. The 4-year survival of the whole cohort was 84% (95% CI: 74-90%). (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Kaplan Meier analysis of the mid-term survival of the whole cohort. The four-year survival was 84% (95% CI: 74-90%).

DISCUSSION

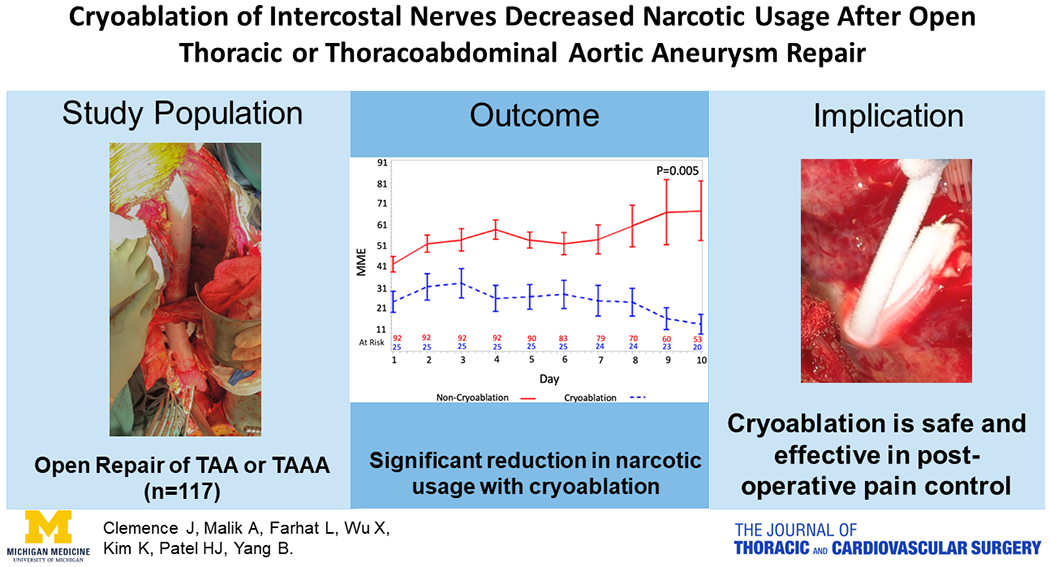

In this study, we found that after open TAA or TAAA repair, patients with cryoablation had significantly decreased average narcotic usage by 28 MME (equal to four 5 mg Oxycodone) each day per patient post-extubation compared to patients without cryoablation with standard pain management (narcotic and non-narcotic medication). The perioperative outcomes were very similar between the two groups, including paralysis, stroke and in-hospital mortality. The key findings and implications of this study were summarized in the graphical abstract. (Figure 4)

Figure 4:

Summary of the study, including study population of open repair of TAA (thoracic aortic aneurysm) or TAAA (thoracoabdominal aneurysm), narcotic usage in patients with or without cryoablation of intercostal nerves, and implication of the outcomes.

Patients who undergo TAA or TAAA repair through thoracotomy or thoracoabdominal incision suffer tremendous incisional pain postoperatively, which compromises patients’ respiratory capacity, mobility, and recovery. Narcotics have been used for pain control; however, they cause gastrointestinal complications, neurological complications and potential risk of dependence, and their effectiveness of pain control is not optimal. Intercostal nerve block with local anesthetics can achieve great pain control, however it only lasts 24-48 hours.10 Epidural injection of analgesia has good results, but it can decrease vascular tone and cause hypotension which is very dangerous in patients after TAA or TAAA repair since hypotension can result in stroke and paraplegia.10 There is also a risk of infection when an epidural catheter is left in patients for days. Because of the limitations of current pain management for patients after TAA or TAAA repair, we explored the cryoablation of intercostal nerves for postoperative pain control.

The method of cryoanalgesia for pain relief was first described in 1976.11 Originally, this technique involved freezing intercostal nerves to −60 °C for 30-45 seconds, causing local damage to the myelin sheath while the neuron axon remains unharmed. This leads to interruption of nerve conduction and pain relief, with the possibility of nerve regeneration in 1-3 months and return of full nerve function once the myelin sheath is regenerated.5, 10, 11 Since first use of cryoablation for pain management was in 1976, there continues to be variability in practice and outcomes demonstrated in the review by Khanbhai et al.6 From our experience, patients with cryoablation behaved very obviously different postoperatively. They had much less pain and consumed much less narcotics. (Figure 2A, 2B) Our study was comparable to other studies that have demonstrated pain reduction with cryoablation. 3 The average pain score for postoperative day 1 for the cryoablation group was 2.3, which was very close to those reported in other studies (pain score around 2.8).3 The pain score went down as time went on despite significantly more thoracoabdominal incisions for TAAA repair (Table 2), longer duration of chest tubes (Table 3) and less consumption of narcotics (Figure 2B) in the cryoablation group. The time for cryoablation in our study was 2 minutes, which was much longer than previous studies (30-40 seconds).5, 10, 11 This might be one of the reasons that our approach worked so well for postoperative pain control. The other reason could be we also cryoablated the intercostal nerves from 3rd to 9th intercostal space if two thoracotomies were used, or two intercostal nerves above and below the thoracotomy if one thoracotomy was used. Our extensive cryoablation of intercostal nerves allowed us to cover a large area of the thoracotomy instead of just one intercostal space above and below the thoracotomy.10 Most of the patients in the cryoablation group reported no pain or minimal pain after extubation. (Figure 1)

Other factors that could contribute to the post-operative pain included age, one vs. two thoracotomies, TAA vs. the TAAA repair, duration of chest tubes, and non-narcotic pain medications (Toradol). Not surprising, older patients complained of less pain and used less narcotics (Table 4). Patients with TAA repair consumed 11 MME fewer narcotics than patients with TAAA repair, and patients with one thoracotomy consumed 9.5 MME more narcotics than two thoracotomies (Table 4), although the differences were not significant, which was most likely due to sample size. In our practice, two thoracotomies were frequently used for TAA repair, and one thoracotomy has been more frequently used for TAAA. This could be the reason for more narcotic usage in patients with one thoracotomy compared to patients with two thoracotomies. Compared to the non-cryoablation group, despite having significantly more thoracoabdominal incisions for TAAA repair and longer duration of chest tubes but similar amount of one vs. two thoracotomies with similar median age, the cryoablation group had a large and significant reduction of average narcotic usage of 28 MME (four 5 mg Oxycodone) per patient per day (Figure 2B, Table 4, Supplemental Table 2). There was one additional dose of Toradol (15 mg) used in the cryoablation group compared to multiple doses of Toradol and in many patients in the non-cryoablation group (Supplemental Table 3). All of these findings indicate the effectiveness of cryoablation of intercostal nerves in treating post-operative pain in open TAA or TAAA repair.

The overall outcomes are very similar between the two groups, including paraplegia. (Table 3). None of the patients developed a unilateral neurological deficit of the lower extremity, indicating the cryoablation had a very low risk of thermal injury to the spinal cord. Only one patient developed permanent paralysis of their lower extremities in the cryoablation group, and it was in the setting of a cardiac arrest. The length of stay was significantly longer in the cryoablation group (15 vs. 11 days) (Table 3), which was likely due to significantly more TAAA repair in the cryoablation group (52% vs. 28%, p=0.03). (Table 2). Nevertheless, cryoablation did not increase other postoperative complications significantly.

Because it was a one-time treatment, there was no risk of infection from any catheter as we see in epidural analgesia or risk of hypotension since cryoablation does not block the sympathetic nervous system as epidural analgesia does. The numbness of the incision lasts about 3 months and gradually recovers. Some patients may continue to have numbness for additional months. Because of the excellent pain control and less usage of narcotics, all of our patients preferred cryoablation, despite the numbness of the incision, when we discussed post-operative pain control with them in the clinic and consented them for the cryoablation. Also, all the aortic surgeons at the University of Michigan have adopted this approach for pain control because of its effectiveness and safeness (no increase of paraplegia). Given the current opioid epidemic in the United States, a lower narcotic need in the cryoablation group was a valuable finding. As physicians, it is our responsibility to meet the pain needs of our patients while decreasing opioid prescribing and the potential for dependence.

One potential side effect, which has been noted in the literature, is the development of neuralgia following cryoablation. The Muller group reported 20% of patients in their cryoablation group developing neuralgia six weeks postoperatively, which gradually disappeared.7 We have not seen patients with postoperative new-onset neuralgia. Most patients felt the skin along the incision was numb and they had no pain during their 3 month visits and annual visits afterward. Our sample size was small in this study. We are using this approach for all of our patients who undergo TAA and TAAA. Hopefully, in the near future, we will have long-term follow up in a large sample size of patients treated with cryoablation. We had only one patient complain of back pain around the incision, close to the spine, 3 months after surgery, which could be attributed to the retraction of thoracotomy. This area was not covered by the cryoablation.

Does the addition of cryoablation increase the overall cost of the treatment? The current cost of the cryoICE probe is approximately $1,700. However, if cryoablation can achieve superior pain control while significantly reducing the usage of narcotics postoperatively, then we think it is worthwhile. Better pain control also could decrease postoperative complications, and length of stay, which could potentially decrease the overall cost of treatment. It could also decrease the cost of medicine itself since less narcotic and non-narcotic medicine (Toradol) were used post-operatively. (Figure 2B, Supplemental Table 3). However, those potential benefits will need further studies with larger sample sizes to prove.

Our study was limited by a single-center and retrospective experience, which was not randomized and has all the limitations of a retrospective study. Our sample size for the cryoablation group was small. However, because of the effectiveness of this approach, we have already seen a significant difference in the consumption of narcotics between the cryoablation and non-cryoablation groups. Because of the small sample size, we did not see a significant difference in pain score and other postoperative complications related to pain control, such as pneumonia and length of ICU stay. The selection of cryoablation was based on individual surgeons’ preference. Although different surgeons performed the procedures, the incisions for the operations were very similar. The operations for TAA or TAAA with cryoablation of intercostal nerves were performed from 2016-2018, and the operations without cryoablation were performed from 2012-2018. However, the surgical strategy to treat TAA or TAAA, and management of postoperative pain were not changed except some patients had cryoablation and some did not. Postoperative pain was predominantly managed by our intensivists, who all use the same protocol (narcotics or non-narcotic medication; no epidural analgesia or intercostal nerve block), and not by surgeons. Because of this, there was minimal bias of different dates of procedures and surgeon bias. This study was also limited by lack of time to ambulation or time to standing alone.

CONCLUSION

With cryoablation of intercostal nerves, postoperative surgical pain was well controlled, and narcotic usage was significantly decreased with no increase of paraplegia or other complications in patients undergoing TAA or TAAA repair. Cryoablation of intercostal nerves is a simple, safe and effective measure for postoperative pain control in TAA or TAAA repair. However, larger prospective investigations and long-term follow-up are needed before definitive recommendations of this technique.

Supplementary Material

Video Legend: Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair with cryoablation of intercostal nerves.

CENTRAL MESSAGE.

Cryoablation of intercostal nerves is effective and safe for postoperative pain control in patients of TAA or TAAA repair.

PERSPECTIVE STATEMENT.

Extensive cryoablation (from 3rd to 9th intercostal nerves) is safe, effective, and simple to apply for postoperative pain control in patients after open TAA or TAAA repair with minimal side effects and significantly decreases the usage of narcotics. Prospective investigations and long-term follow-up are needed to make definitive recommendations of this technique.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Dr. Yang is supported by the NHLBI of NIH K08HL 130614 and R01HL141891, Phil Jenkins and Darlene & Stephen J. Szatmari Funds.

GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS

- BAV

bicuspid aortic valve

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CVA

cerebral vascular accident

- HCA

hypothermic circulatory arrest

- ICU

intensive care unit

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MME

measured morphine equivalents

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- SMA

superior mesenteric artery

- TAA

thoracic aortic aneurysm

- TAAA

thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None related to this study

REFERENCES

- 1.Warner DO. Preventing Postoperative Pulmonary Complications. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottschalk A, Cohen S P, Yang S, Ochroch A. Preventing and Treating Pain after Thoracic Surgery. Anestesiology.2006;104:594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz J, Nelson W, Forest R, Bruce D. Cryoanalgesia For Post-Thoracotomy Pain. The Lancet. 1980;315:512–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynn CJ, Lloyd JW, Barnard JD. Cryoanalgesia in the management of pain after thoracotomy. Thorax. 1980;35: 325–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maiwand O, Makey AR. Cryoanalgesia for relief of pain after thoracotomy. British Medical Journal. 1981;282:1749–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanbhai M, Yap KH, Mohamed S, Dunning J. Is cryoanalgesia effective for post-thoracotomy pain? Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2013;18:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller L, Salzer G, Ransmayr G, Neiss A Intraoperative cryoanalgesia for postthoracotomy pain relief. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery.1989;48:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating Total Daily Dose of Opioids for Safer Dosage. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. April 07, 2019.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. National death index. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm. October 1, 2019.

- 10.Detterbeck FC. Efficacy of Methods of Intercostal Nerve Blockade for Pain Relief After Thoracotomy. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2005;80:1550–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd JW, Barnard JD, Glynn CJ. Cryoanalgesia. A New approach to pain relief. The Lancet. 1976;2:932–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video Legend: Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair with cryoablation of intercostal nerves.