Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of interprofessional case conferences on home-based end-of-life care to bridge perceptions gaps regarding ethical dilemmas among different healthcare professionals and analyze essential issues extracted the interprofessional discussions.

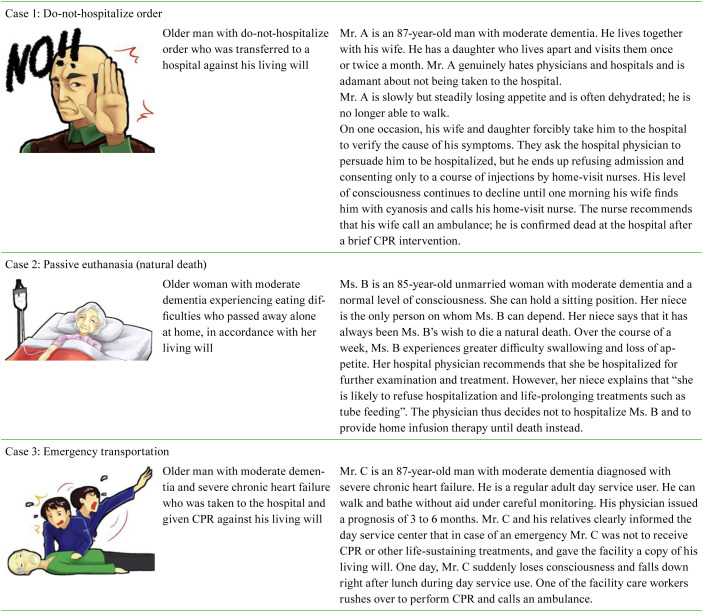

Patients and Methods: The participants could spend only a limited amount of time after their working hours. Therefore, we shortened and simplified each of three case scenarios so that the discussions do not last longer than 90 minutes. For the case conferences, we selected 3 cases, which entailed the following ethical dilemmas pertaining to home-based end-of-life care: refusal of hospital admission, passive euthanasia, and emergency transport. Participant responses were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using qualitative content analysis and Jonsen’s four topics approach.

Results: A total of 136 healthcare professionals (11 physicians, 35 nurses, and 90 care workers) participated in the case conferences. The physicians, nurses, and care workers differed in their perceptions of and attitudes toward each case, but there were no interprofessional conflicts. Despite the short duration of each case conference (90 minutes), the participants were able to discuss a wide range of medical ethical issues that were related to the provision of appropriate home-based end-of-life care to older adults. These issues included discrimination against older adults (ageism), self-determination, an unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication, insufficient end-of-life care skills and education, healthcare costs, and legal issues.

Conclusion: The physicians, nurses, and care workers differed in their perceptions of and attitudes toward each case, but there were no interprofessional conflicts.

Keywords: interprofessional education, palliative care, ageism, advance care planning

Introduction

A majority of older adults wish to spend the last days of their lives at home or in a long-term care facility rather than receive medical care in hospitals1,2,3) because they feel more comfortable staying in a familiar environment4). Multidisciplinary approaches are needed to adequately fulfill the needs of older adults who often have complex and specific biopsychosocial and functional disorders5). Thus, comprehensive interprofessional collaborative practices that involve clients, family members, neighbors, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and care workers (e.g., care managers and professional caregivers) are likely to yield better results than traditional physician-patient approaches, which generally fail to fulfill their unique needs6, 7). Accordingly, in 2012, the Japanese government established a community-based integrated care system, which aimed to offer the best possible end-of-life care to older adults in community settings8).

Within the framework of the community-based integrated care system, interprofessional education has been the focus of increasing attention9,10,11). Interprofessional discussions concerning patient care planning are commonly facilitated within the Japanese long-term care insurance system12). Interprofessional and inter-workplace case conferences, which are a central feature of interprofessional education, improve the communication skills of healthcare professionals13). Specifically, end-of-life cases that involve sensitive moral and ethical issues serve as good educational case scenarios because perceptions of ethical dilemmas vary considerably across different healthcare professionals14, 15).

However, few studies have focused on the operational process and practice of community-based interprofessional case conferences. Moreover, interprofessional differences in perceptions of ethical dilemmas among conference participants have not been adequately investigated. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of interprofessional case conferences on home-based end-of-life care to bridge perception gaps regarding ethical dilemmas among different healthcare professionals and analyze essential issues extracted the interprofessional discussions.

Methods

Conference preparation

We created a multidisciplinary working group on the case conference program at Nagoya University in April 2017. This group (N=10 professionals) consisted of 3 physicians, 1 public health nurse, 1 nurse, 1 pharmacist, and 4 care managers. The working group decided that the conference would focus on helping participants tackle the various ethical issues that are involved in the provision of home-based end-of-life care. The group also delineated the conference procedures and created model cases about ethical dilemmas. The group members chose these model cases from a list of cases, which had previously been discussed in other interprofessional end-of-life care workshops16, 17) and ethics case conferences. Because the participants could spend only a limited amount of time after their working hours, we shortened and simplified each case scenario so that the discussions do not last for more than 90 minutes (Table 1). Finally, 3 cases, which entailed the following ethical dilemmas pertaining to home-based end-of-life care, were discussed during the case conferences: refusal of hospital admission, passive euthanasia, and emergency transport (Table 2).

Table 1. Outline content.

| 0:00-0:10 | Opening | Introduction and welcome |

| 0:10-0:35 | Session one | Case 1: Refusal of hospital admission |

| 0:35-1:00 | Session two | Case 2: Passive euthanasia |

| 1:00-1:25 | Session three | Case 3: Emergency transport |

| 1:25-1:30 | Wrap-up |

Table 2. Ethical scenarios at the conferences.

Conference arrangement

We established conference coordinating offices in 5 regions in the country: Tohoku, Tokai, Kansai, Shikoku, and Kyushu. Each office was instructed to recruit a number of conference participants. Healthcare professionals who were involved in community-based integrated care were eligible for inclusion. The eligibility requirements were intentionally to be unspecific to secure participation of a variety of occupational backgrounds including physicians, nurses, and care workers. Between February 2016 and July 2017, the first author (YH) conducted and facilitated the interprofessional case conferences on home-based end-of-life care in each city. In each conference, the participants were divided into 6–8-member interprofessional and inter-workplace groups. In each session, the facilitator provided the participants with a brief description of the case scenario, following which the group members participated in the group discussions. To enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the conference, the participants were given several simple directives such as “Share your personal opinions”, “Stay on topic”, and “Speak clearly”. They were also instructed to respond with single-word utterances or short phrases one after another. The discussions continued until the participants had no new ideas to articulate. At the end of the conference, the facilitator conducted a brief wrap-up and feedback session.

Analysis

Participant responses were audio-recorded and transcribed. Next, their utterances were compiled into single-sentence labels (i.e., units of meaning). The labels were sorted out across 3 professional categories: physicians, nurses, care workers (care managers and professional caregivers). Using qualitative content analysis, the labels were categorized and structured inductively18). First, the most representative labels were selected and organized into groups by the first author and an assistant; labels belonging to the same group that shared strong qualitative similarities were integrated into a single label. Second, a key phrase, which captured the core meaning of the group labels, was coined for each group. Finally, the different groups of labels were organized using Jonsen’s four topics approach19), which is a widely used framework that has been designed to facilitate the identification and visualization of discussion points in clinical ethics case analyses. The four topics are medical indication, patient preferences, quality of life (QOL), and contextual features.

This study was approved by the Bioethics Review Committee of Nagoya University School of Medicine prior to the investigation (approval number: 2015-0444). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Results

A total of 136 healthcare professionals (11 physicians, 35 nurses, and 90 care workers) participated in the case conferences. The sample consisted of 21 males (15.4%) and 115 females (84.6%). Their mean age was 49.1 (SD=9.8, range=22–76) years, and mean years in practice was 17.5 (SD=10.1, range=1–39) years.

The themes, subthemes, and units of meaning that emerged from the data are shown in Table 3. Although the four topics approach was not explained to the participants either before or during the conference, all the issues that were subsumed under the four topics were discussed at length. Although the participants did discuss the issue of QOL during the conference, they did not discuss pertinent themes as extensively as they discussed the other topics. A summary of the key discussion points for the three cases is presented in the following sections.

Table 3. Differences in focuses of attention among physicians, nurses, and care workers.

| Case | Physician | Nurse | Care worker | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical indication | Physician-patient communication | Physician-patient communication | |

| Emergency response planning discussion/conference for specific patient | Emergency response planning discussion/conference for specific patient | |||

| Nurse’s role as mediator | No other choice | |||

| Greater hospital involvement | ||||

| Patient preferences | Unreliable informed choice | Unreliable informed choice | Unreliable informed choice | |

| Flexible advance care planning management | Clear and firm decisions on the part of patients and families | |||

| Fusion of at-home care planning and ACP | ||||

| QOL | Process rather than outcome | |||

| Contextual features | Unsuccessful inter-professional collaboration | Daughter’s support expected | Daughter’s support expected | |

| Inapplicability of compulsory hospitalization system | Bereaved family care | Bereaved family care | ||

| Inadequate support from wife | ||||

| Meddling by someone else | ||||

| Family satisfaction | ||||

| Avoidance of postmortem examination | ||||

| Taboo of talking about death | ||||

| 2 | Medical indication | Natural death | Natural death | Careful medical examination |

| Careful medical examination | Feeling of guilt toward passive euthanasia | Satisfaction with medical treatment | ||

| Patient preferences | Frequent monitoring | Frequent monitoring | Documentation | |

| Unreliable informed choice | Unreliable informed choice | Unreliable informed choice | ||

| Good death as wished | No patient involvement in decision-making | Active intervention in conflicts between patient and family | ||

| QOL | Loss of food enjoyment | Assessment of living arrangement | ||

| Contextual features | Bereaved family care | Apprehension about lengthy caregiving | Apprehension about lengthy caregiving | |

| Widespread recognition of natural death | Wish for prolonged life | No daughter to rely on | ||

| 3 | Medical indication | Emergency response planning discussion/conference for specific patient | Emergency response planning discussion/conference for specific patient | Emergency response planning discussion/conference for specific patient |

| Expected turn for the worse | Unexpected turn for the worse | |||

| Difficult judgement | ||||

| Need to remain calm | ||||

| Patient preferences | Urgent contact with family | Changeable wishes | ||

| DNACPR as a good practice | Difficult-to-understand end-of-life options | |||

| Concrete action plan | ||||

| QOL | Place of recreation and relaxation | QOL-centered plan | ||

| Contextual features | First-aid skills everyone should know | Improper place for end-of-life care | Improper place for end-of-life care | |

| Infringement of autonomy | Potential lawsuit | Potential lawsuit | ||

| Institution’s lack of readiness | Standardized emergency procedure | |||

| High medical fees | Empathy for caring staff | |||

| Legal importance of medical records | ||||

Medical indication

Successful home-based end-of-life care is contingent on the development of strong relationships between physicians, patients, and family members. Unfortunately, a home care physician was not involved in case 1. The participants inferred that the patient’s wife probably felt as though she had no other choice but to request the home-visit nurse to arrange for hospitalization; this is likely to have helped her cope with the mental conflict that she experienced when she acted contrary to her husband’s will. The participants noted that an emergency preparation simulation may have helped her be better prepared to make such decisions.

Some participants perceived case 2 positively because the dying process unfolded naturally and painlessly. However, others contended that a clinical evaluation (including a thorough review of patient history and physical examination) should have been conducted to ascertain the possibility of recovery. Even though it remains uncertain whether peripheral intravenous fluid therapy is effective at the end of life, many physicians choose to perform this procedure on a dying patient primarily for ethical reasons. Specifically, if they do not perform any medical procedure, they may end up feeling guilty. The general public perceives the overuse of tube feeding to be a serious medical ethical problem. Enteral tube feeding is commonly used with patients with advanced dementia and other life-threating diseases whose nutritional intake is poor. However, there is insufficient evidence to claim that this practice is beneficial to such patients, especially because they cause distress and pain. The participants were hopeful that such patients would eventually be able to avoid life-sustaining treatments (e.g., tube feeding) and experience a “natural death”.

Case 3 was a patient who had experienced severe heart failure, which can cause acute deterioration or cardiac arrest. Accordingly, several participants argued that the staff members of the healthcare facility should have prepared for this type of an emergency by convening an inter-workplace preparatory conference. However, some participants noted that even experienced physicians find it difficult to arrive at an accurate prognosis for heart failure. In this particular case, the physician had given him a six-month prognosis. Other participants emphasized that non-medical care workers do not possess the ability to judge whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is indicated or contraindicated.

Patient preferences

In case 1, it is very important that older people and their relatives be fully aware of the risks involved in dying at home and be prepared to handle emergencies. Advance care planning (ACP) is a process that enables individuals to convey their preferences and future healthcare and end-of-life care options to family caregivers and healthcare professionals. The participants underscored the importance of establishing realistic and flexible advanced care plans. In this particular case, they were skeptical about the accuracy and reliability of ACP for several reasons: the patient did not possess the ability to make any decisions because he had dementia, talking about death is still considered taboo in Japanese society, and the patient was most likely unable to understand his medical condition or related events. The participants believed that the patient’s wife may not have openly expressed her wishes to the physician, as is often the case with Japanese older adults. They also recommended that home-visit nurses or care workers should play a more active role in implementing ACP as a part of public long-term care plans.

With regard to case 2, the participants debated the validity of ACP and made the following observations: a) owing to cognitive impairment, the patient may have lost the ability to make sound treatment decisions; b) the patient may have been reluctant to express her wishes because she wanted to avoid bothering her niece; c) the patient’s preferences may have changed over time, but they were not revisited when her medical condition deteriorated; and d) it may have been difficult for the patient to understand the end-of-life care options that were available to her (e.g., resuscitation and mechanical ventilation). The patient’s niece and physician made treatment decisions on her behalf without considering her most recent feelings and preferences. Therefore, the participants noted that healthcare professionals should be actively involved in the ACP process (including processes such as documentation and monitoring).

When discussing case 3, some participants contended that the staff members should not have performed CPR against the patient’s wishes. Some participants underscored the importance of monitoring the preferences of older adults and their families because end-of-life preferences can change over time as one nears death. Further, it is difficult for laypersons to understand the details of their end-of-life care options.

QOL

When discussing case 1, one physician observed that successful end-of-life care is contingent on how rather than where a person dies.

Food plays a vital role in maintaining QOL and general wellbeing. Therefore, options for oral nutrition support should always be considered to meet the requirements of patients with inadequate food and fluid intake, unless they cannot eat safely because of swallowing disorders or gastrointestinal problems. Some participants believed that case 2 had not been treated properly. Indeed, the patient had not been tested or treated for appetite loss, and she received only peripheral intravenous drip. During the conference, several participants mentioned that they required more information about the patient’s daily life environment to consider her QOL.

The participants inferred that case 3 probably felt at ease in the day service center that he regularly visited and found it comforting that he could spend the very last moments of his life in a familiar environment.

Contextual features

Case 1 had made it clear that he did not want to be hospitalized. Therefore, his healthcare team was required to assist his family caregivers in providing home-based end-of-life care when he was dying. However, the decision to call an ambulance was perceived to be justifiable because it offered some relief to his anguished family caregivers. Further, when a person dies at home, the police order an autopsy of the deceased person. Therefore, the wife may have been very worried that the authorities may learn that the physicians had not been regularly visiting the patient at his home. She may have also feared that her family members would blame her for not taking appropriate actions. Because the patient’s decision to die at home was a difficult one for his wife to honor, the participants contended that her daughter and the care team should have been more actively involved in his end-of-life care. Several participants also emphasized the need for bereaved family care because, ultimately, the wife and daughter may have regretted their decision to take the patient to the hospital.

When discussing case 2, the participants observed that the patient’s niece may not have experienced as strong a sense of caregiver responsibility as a biological daughter would have. They believed that she probably felt that she had done all that she could and that she could not provide care anymore. Several participants believed that the patient’s niece may have wanted her aunt to live a little longer, and they highlighted the importance of bereaved family care. Some participants explained that many individuals perceive natural death as a positive event and that promoting greater acceptance of natural death will alleviate the mental anguish that bereaved relatives experience.

Day service centers are quite popular among older adults, even those who are relatively healthy; therefore, they are usually rather crowded. Thus, when discussing case 3, the participants speculated that it may have been difficult for the staff members to secure some space within which they could perform CPR. Moreover, the participants emphasized that emergencies are inevitable and noted that the day service center staff members would have been better prepared to handle this situation if they had been provided with a manual or appropriate CPR training. The participants underscored several important ethical and legal dilemmas surrounding the decision to call for emergency transportation, including the bereaved family members’ dissatisfaction with the decision to go against their loved one’s wishes and the high medical expenses. In addition, the need to provide psychological support to the bereaved family members and staff who were involved in these events was also discussed. Some participants recommended that informed decisions regarding resuscitation should be documented in nursing and medical records to weaken the impact of many of the ethical and legal challenges that surround such types of cases.

Differences in responses between physicians, nurses, and care workers

With regard to cases 1 and 3, medical indication was predominantly discussed by the physicians and nurses, whereas contextual features were primarily discussed by the nurses and care workers (Tables 4–6

Table 5. Quotes about case 2.

| Medical indication | ||

| Careful medical examination | “The possibility of recovery from imminent death should be carefully considered in this case.” (Physician) | |

| “Since the cause of her appetite loss is unknown, medical examination and treatment should have been performed.” (Care manager) | ||

| Natural death | “I believe that the patient passed away peacefully, avoiding painful medical examinations and treatment.” (Physician) | |

| “I believe that this case was successful because the patient wasn’t forced to receive life-sustaining treatments such as tube feeding.” (Nurse) | ||

| Feeling of guilt about passive euthanasia | “The niece probably felt sorry for not providing proper care and attention to her aunt and for letting her die naturally.” (Nurse) | |

| Satisfaction with medical treatments | “Normally, in end-of-life situations, family caregivers are likely to wish for a certain level of medical treatment.” (Care worker) | |

| Patient preferences | ||

| Good death as desired | “I believe that this patient died peacefully in accordance with her end-of-life care wishes, although these differed from her niece’s.” (Physician) | |

| Unreliable informed choice | “It is difficult for people to choose the right treatment for themselves because the life-sustaining treatment options are difficult to understand.” (Physician) | |

| “Although the patient wished to die naturally, I don’t believe that she meant to refuse all treatment.” (Nurse) | ||

| “The pros and the cons of the tube feeding option should have been fully explained to the patient.” (Care worker) | ||

| Documentation | “Had the patient’s wishes been documented, they would have served as a support for discussion between the physician and the patient’s niece, and this might have eased the niece’s burden and stress.” (Care worker) | |

| Frequent monitoring | “Because people’s end-of-life wishes often vary near death, the wishes of the patient and her family should have been monitored frequently as the patient approached death.” (Physician) | |

| “Because the patient’s wishes concerning end-of-life care nearing death could have evolved with time, her ACP should have been checked again.” (Nurse) | ||

| Active intervention in conflicts between patient and family | “The physician or nurse should encourage the patient’s autonomy of decision with respect to his living will and end-of-life wishes rather than implicate relatives in surrogate decision making.” (Care worker) | |

| No patient involvement in decision-making | “It looks like the final decision was made through physician-niece communication; I am concerned that the patient’s autonomy of decision was ignored.” (Nurse) | |

| QOL | ||

| Loss of food enjoyment | “I feel sorry that the patient could not eat her favorite food due to eating problems and was given drip infusion treatment.” (Nurse) | |

| Assessment of living arrangement | “I think that the patient’s living situation and feasibility of home end-of-life care should have been considered.” (Care manager) | |

| Contextual features | ||

| No biological daughters | “In a sense, it was good that the patient had a niece and not a daughter to look after her because a daughter might have pressured her to make choices she was not comfortable with, due to their close bond.” (Care manager) | |

| Wishes for prolonged life | “I think that the patient’s niece probably inwardly wished that her aunt would be given life-sustaining treatment and live as long as possible.” (Nurse) | |

| Apprehension about lengthy caregiving | “Because the niece is the patient’s only remaining relative, she might be worried about the excessive caregiver burden she would have to assume should her aunt live to a very old age.” (Nurse) | |

| “The niece is probably not very young, since her aunt is 85, and she may not be able to support the patient on a daily basis for a lengthy period of time.” (Care worker) | ||

| Bereaved family care | “Because the shock and grief of losing a loved one may feel overwhelming, it is vital that the patient’s niece be offered post-bereavement care.” (Physician) | |

| Widespread recognition of natural death | “People need to realize that withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining therapies is ethical and medically appropriate in some circumstances.” (Physician) | |

). There were no noteworthy differences between the different professional groups for cases 1 or 2. However, when discussing case 3, the physicians were more inclined to report that the sudden death was predictable than the nurses were. Moreover, the physicians perceived the actions of the healthcare providers to be a violation of the patient’s do-not-resuscitate order. In contrast, the nurses and care workers underscored the possibility of a lawsuit.

Table 4. Quotes about case 1.

| Medical indication | ||

| Physician-patient communication | “Lack of physician involvement made it difficult for the patient to die at home.” (Physician) | |

| Nurse’s role as mediator | “I think that contacting the home visit nurse helped the wife deal with the conflicting emotions she had in honoring her husband’s wish not to be hospitalized.” (Physician) | |

| Prior simulation | “Because no end-of-life care plan had been outlined due to the patient’s dementia, his wife probably panicked and took him to the hospital.” (Physician) | |

| “Before initiating the home-visit nursing care service, the multidisciplinary team should have had simulation training to learn how to best prepare to provide home end-of-life care until the very last moment of life.” (Nurse) | ||

| No other choice | “Since the wife lived alone with the patient and could not rely on anyone for help, she must have been upset; so I think that calling the home-visiting nurse and ambulance was the best option for her.” (Nurse) | |

| Greater hospital involvement | “Because the patient’s wife and daughter put considerable effort into convincing the patient to go to the hospital, I think that greater hospital involvement and support would have helped comfort them.” (Nurse) | |

| Patient preferences | ||

| Clear and firm decisions of patients and families | “I believe that ACP would have helped the wife keep her composure.” (Nurse) | |

| Untrustworthy informed choice | “This case teaches us the difficulty in accurately assessing the end-of-life wishes of people with dementia.” (Physician, Nurse) | |

| “Although the patient decided to spend the last days of his life at home, I am still skeptical about whether or not he understood the pros and cons of home end-of-life care versus hospitalization.” (Care worker) | ||

| Flexible advance care planning management | “A positive aspect of this case is that the patient was able to spend the last days of his life at home as he wished.” (Physician) | |

| Fusion of in-home care planning and ACP | “His care manager should have provided relevant information to discuss his medical treatment preferences as well as more specific aspects of his end-of-life wishes.” (Nurse) | |

| QOL | ||

| Process rather than outcome | “I think that successful end-of-life depends on how rather than where a person dies.” (Physician) | |

| Contextual features | ||

| Family satisfaction | “The patient’s wife and daughter were probably relieved that death occurred at the hospital because taking care of a patient with severe dementia at home is demanding and stressful for family caregivers.” (Care worker) | |

| Expected daughter’s support | “I think that the patient’s daughter was very eager to take care of her father because she visited him very frequently.” (Nurse) | |

| “Had the patient’s daughter been at his home around the time of his death, his wife would probably have been able to better handle the situation and avoid taking him to the hospital.” (Care worker) | ||

| Precarious wife’s support | Precarious wife’s support | |

| “I strongly believe that his wife was too old to safely provide long-term end-of-life care.” (Care worker) | ||

| Meddling by someone else | “When opting for home end-of-life care, relatives are likely to insist that the patient be hospitalized if an emergency occurs. Family caregivers must therefore be prepared to deal with this if they decide to provide end-of-life care at home until death.” (Care worker) | |

| Avoidance of postmortem examination | “When a person does not have a physician and dies at home, police officers are required to visit and perform a post mortem examination to determine the cause of death. So, it might be best for the bereaved family to hospitalize the patient (if the bereaved family is worried about what the neighbors will think).” (Care worker) | |

| Bereaved family care | “I am worried what the bereaved will regret transferring their loved one to the hospital against his will.” (Nurse) | |

| “The bereaved relatives may think that they should have provided care at home until the last moment.” (Care worker) | ||

| Unsuccessful inter-professional collaboration | “The problem here is that nobody knows who is coordinating this patient’s care.” (Physician) | |

| Inapplicability of compulsory hospitalization system | “Unlike admission to a psychiatric hospital which is imposed, in this case they cannot force the patient to be hospitalized.” (Physician) | |

| Taboo of talking about death | “Because talking about death is still taboo in Japan today, relatives may prefer to avoid discussing the patient’s end-of-life care wishes.” (Care worker) | |

Table 6. Quotes about case 3.

| Medical indication | ||

| Expected sudden turn for the worse | “This was to be expected because of the patient’s advanced age of 87 and chronic heart condition.” (Physician) | |

| Unexpected sudden turn for the worse | “Because the physician’s prognosis was 3 to 6 months, the patient’s sudden cardiac arrest seemed unexpected, but withholding acute resuscitation could not be avoided.” (Nurse) | |

| Prior simulation | “Since the patient and his family had a clear do-not-resuscitate order, the physician and other professionals should have worked together with the care team members to avoid an undesirable CPR intervention.” (Physician) | |

| “Even though there is no descriptions of the patient using home care services, it is possible that the patient was nevertheless being followed by a home visiting nurse. If that was the case, the nurse should have prepared the family to deal with emergencies without calling an ambulance.” (Nurse) | ||

| “The patient’s end-of-life care team should have agreed on the best way to meet every possible contingency in advance.” (Care worker) | ||

| Cool head | “In case of an emergency, the staff should try to remain calm even though, understandably, this type of situation is likely to stir emotions.” (Physician) | |

| Difficult judgment | “Handling the emergency response places a huge burden on the facility and that is why I think the ambulance or the physician should take that responsibility.” (Physician) | |

| Patient preferences | ||

| Concrete action plan | “The “no CPR” order is so vague that even health care professionals do not understand what to do in case of an emergency.” (Physician) | |

| Urgent contact to family | “They should have called his relatives and asked whether or not they should perform CPR and take him to the hospital.” (Physician) | |

| Changeable wishes | “Even if the patient and his relatives are in agreement about not resuscitating, once the patient dies, bereaved family members sometimes complain that no resuscitation attempts were made.” (Care worker) | |

| Difficult-to-understand end-of-life options | “I think that the staff might perform CPR because they are not certain the patient and his relatives can fully understand the merits and demerits of CPR.” (Care worker) | |

| Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation as a good practice | “Since calling an ambulance means requesting CPR, they should not have performed CPR against the patient’s will.” (Physician) | |

| QOL | ||

| QOL-centered plan | “His relatives might have let him go to day service because they wanted him to spend the last months of his life with dignity.” (Care worker) | |

| Place of recreation and relaxation | “There are now home visiting bathing services for severely ill patients. I hope that more and more professional caregivers will take over end-of-life care at home or home-like facilities to provide a comfortable environment to these patients.” (Nurse) | |

| Contextual features | ||

| Legal importance of medical records | “A copy of the patient’s living will should have been kept in the nursing records as well as the physician’s medical records.” (Nurse) | |

| Institution’s lack of readiness | “Facility management should take responsibility for hosting older people with a risk of sudden cardiac arrest due to severe heart failure. The staff should not be blamed for performing CPR.” (Nurse) | |

| Improper place for end-of-life care | “Day service centers are not the right place to die both from a “hard” and “soft” perspective, and the staff’s burden in providing end-of-life care for older clients to the end should be taken into account.” (Nurse) | |

| “With other day service users watching the emergency unfold, it might have been difficult for the staff to remain next to the dying patient without doing anything.” (Care worker) | ||

| Empathy for caring staff | “The care team showed empathy for the staff performing CPR who might feel ill-at-ease.” (Care worker) | |

| First-aid skills everyone should know | “Staff other than medical professionals should be able and ready to perform acute resuscitation whenever needed.” (Physician) | |

| Standardized emergency procedure | “The facility needs to have an emergency manual listing the immediate actions to be taken in case of an emergency, such as transfer to a treatment room or hospital.” (Care worker) | |

| Potential lawsuit | “The staff could not confirm whether the patient’s cardiac arrest was due to heart failure and thus felt obligated to perform acute resuscitation for fear of a possible lawsuit.” (Nurse) | |

| “I believe that the staff performed acute resuscitation to avoid losing a lawsuit.” (Care worker) | ||

| Infringement of autonomy | “The patient and relatives might have grievances about the ambulance call made against their wishes.” (Physician) | |

| High medical fees | “I don’t think it fair for the family to be charged high medical fees for a service provided against their will.” (Nurse) | |

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to examine perception gaps regarding ethical dilemmas pertaining to home-based end-of-life care among different healthcare professionals. The physicians, nurses, and care workers differed in their perceptions of and attitudes toward each case, but there were no interprofessional conflicts.

This action research study is the first to have developed a quick and efficient interprofessional ethics case conference system that pertains to home-based end-of-life care and analyzed the shared contents. The Japan Geriatric Society has identified several key ethical issues that pertain to the provision of appropriate end-of-life care to older adults: discrimination against older adults (i.e., ageism), self-determination, the unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication, insufficient end-of-life care skills and education, healthcare costs, and legal issues20). In our study, the conference participants were able to discuss a wide range of medical ethical issues pertaining to home-based end-of-life care within a limited span of 90 minutes. However, because of a lack of detailed information about each patient’s life circumstances, they were unable to discuss the issue of QOL elaborately. Although the issue of QOL did emerge during the discussions, the participants did not delve deeply into this topic. Previous literature shows that it is still difficult for many people to understand and consistently use the phrase QOL itself and categorize QOL measures21). Consequently, QOL remains largely misunderstood by healthcare professionals. In hindsight, we believe that the conference participants should have been provided with an effective structured discussion guide to which they could have referred before and during the discussions.

Ageism is defined as an act of discrimination that is based on one’s numeric age. with a stigmatizing property frequently cited as a component of poor quality care for the elderly people22). The Japan Geriatric Society has taken a clear stand against undertreatment that is motivated by ageism20). In case 2, participants underscored the importance of carefully considering the need for medical examination before deciding to allow the patient to die naturally, given that there was a risk that under-medication might be perceived as ageism.

The physicians, nurses, and care workers who participated in the conferences contributed to in-depth discussions on ACP, and they acknowledged the importance of ACP documentation. ACP is an important process that allows individuals to consider and decide how they would like to be cared for, if they were to become seriously ill4, 23). A growing number of Japanese older adults and healthcare professionals are starting to realize that it is important to talk about ACP; however, very few of them actually discuss this subject. This may be attributable to several barriers such as Japanese people’s unique beliefs about life and death, patients’ submissive attitudes toward medical professionals, a fatalistic acceptance of their life circumstances, and the taboo of talking about death4, 20, 24). Further, because of inadequate time to discuss ACP in community settings, physicians and nurses may not be able to fully understand the wishes of older adults. It is for this reason that other healthcare workers are expected to discuss ACP more actively25, 26).

Our interprofessional conferences afforded physicians the opportunity to comprehend the importance of providing care to family members, especially bereaved family members. This is an essential component of high-quality end-of-life care. However, some studies have found that empathy levels decline as students progress through medical school and are lower than the ideal level among physicians27, 28). In our study, the nurses and care workers were more likely to express empathy toward older adults and their family members than the physicians were. Past studies have found that nurses and care workers receive more training on how to skillfully interact with older adults and their families and are better equipped to demonstrate compassion and empathy toward them29, 30).

Our results, especially those that pertain to case 3, underscore the importance of enhancing readiness for the provision of end-of-life and emergency care in long-term care settings. Providing end-of-life care in long-term care facilities is extremely challenging for several reasons, some of which are as follows: the patient’s next of kin may not be familiar with death and dying outside a hospital; there may be contrasting opinions among family members or between family members, physicians, and other care workers; educational and training programs that impart the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that are essential for the provision of end-of-life care may not be provided to care workers; and facilities that lack palliative care units or guidelines for providing end-of-life and emergency care to older adults may not be prepared to provide appropriate care31,32,33,34,35). Several participants recommended that day service centers should develop an end-of-life and emergency care procedure manual.

As for the legal implications of case 3, participants pointed out the lawsuit risks regardless of action on the part of the facility. If the care providers had not performed CPR or transferred the patient to the hospital, the bereaved family members may have sued them for failing to perform CPR and eliminating the possibility of recovery. In contrast, by performing CPR and taking the patient to the hospital, they had rendered themselves vulnerable to potential litigation for going against the patient’s will or family members’ preferences or resorting to an aggressive and expensive treatment option at the cost of patient QOL.

This study has some limitations. First, because of interprofessional communication difficulties, value differences, and blurred job boundaries, differences of opinions are common among healthcare professionals36,37,38). However, we did not list the specific divergences among professional categories during the discussion. To optimize the effectiveness of the brainstorming process, we instructed the participants to adhere to a set of helpful ground rules such as “Treat everyone as your equals” and “Take turns speaking; do not engage in side conversations”. However, the traditional hierarchical relationship that exists between doctors and nurses or care workers was clearly evident39,40,41). Further, across all the case conferences, the group facilitator was a physician; this may have prevented the participants from sharing their honest thoughts and opinions. Second, since the cases that were discussed involved legal issues, lawyers were invited to participate in these discussions. However, very few of them accepted our invitation. Moreover, several allied healthcare professionals (e.g., social workers) were invited to participate in the conferences, but their intervention was extremely limited. Third, the short duration of the conference sessions may have hindered extensive brainstorming. Finally, to facilitate the brainstorming process, the participants were asked to provide descriptive responses to a single abstract open-ended question (i.e., “What are your thoughts about this case?”). Therefore, some participants may have experienced difficulties in identifying the underlying ethical issues that they were required to discuss.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of interprofessional case conferences on home-based end-of-life care to bridge perception gaps regarding ethical dilemmas among different healthcare professionals and analyze essential issues extracted the interprofessional discuss. The physicians, nurses, and care workers differed in their perceptions of and attitudes toward each case, but there were no interprofessional conflicts. This action research study was successful in developing a quick and efficient interprofessional ethics case conference system that pertains to home-based end-of-life care.

Acknowledgments

This research study was funded by the Pfizer Health Research Foundation and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17K08912). We acknowledge the valuable contributions of all the conference participants.

References

- 1.Fukui S, Yoshiuchi K. Associations with the Japanese population’s preferences for the place of end-of-life care and their need for receiving health care services. J Palliat Med 2012; 15: 1106–1112. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukui S, Yoshiuchi K, Fujita J. Japanese people’s preference for place of end-of-life care and death: a population-based nationwide survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 42: 882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishie H, Mizobuchi S, Suzuki E. Living will interest and preferred end-of-life care and death locations among Japanese adults 50 and over: a population-based survey. Acta Med Okayama 2014; 68: 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirakawa Y, Chiang C, Hilawe EH. Content of advance care planning among Japanese elderly people living at home: a qualitative study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 70: 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015; 15: 673–687. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morikawa M. Towards community-based integrated care: trends and issues in Japan’s long-term care policy. Int J Integr Care 2014; 14: e005. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsutsui T. Implementation process and challenges for the community-based integrated care system in Japan. Int J Integr Care 2014; 14: e002. doi: 10.5334/ijic.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatano Y, Matsumoto M, Okita M. The vanguard of community-based integrated care in Japan: the effect of a rural town on national policy. Int J Integr Care 2017; 17: 2. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asakawa T, Kawabata H, Kisa K. Establishing community-based integrated care for elderly patients through interprofessional teamwork: a qualitative analysis. J Multidiscip Healthc 2017; 10: 399–407. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S144526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karim R. Building interprofessional frameworks through educational reform. J Chiropr Educ 2011; 25: 38–43. doi: 10.7899/1042-5055-25.1.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levett-Jones T, Burdett T, Chow YL. Case studies of interprofessional education initiatives from five countries. J Nurs Scholarsh 2018; 50: 324–332. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakoso T. A study on team management functions in service manager meetings: leadership empowerment and teamwork expansion based on core users. Sosharu Waku Gakkaishi. 2012; 24: 29–41(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furman M, Harild L, Anderson M. The development of practice guidelines for a palliative care multidisciplinary case conference. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell G, Cherry M, Kennedy R. General practitioner, specialist providers case conferences in palliative care--lessons learned from 56 case conferences. Aust Fam Physician 2005; 34: 389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell G, Zhang J, Burridge L. Case conferences between general practitioners and specialist teams to plan end of life care of people with end stage heart failure and lung disease: an exploratory pilot study. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 24. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirakawa Y. Care manager as a medical information source for elderly people. Med Res Arch 2016; 4: 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirakawa Y, Chiang C, Haregot Hilawe E. Formative research for the nationwide promotion of a multidisciplinary community-based educational program on end-of-life care. Nagoya J Med Sci 2017; 79: 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004; 24: 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumann JH, Alfandre D. Clinical ethical decision making: the four topics approach. Semin Med Pract 2008; 11: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iijima S, Aida N, Ito H. Japanese Geriatric Society Ethics Committee.Position statement from the Japan Geriatrics Society 2012: End-of-life care for the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014; 14: 735–739. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHOQOL Group,The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998; 46: 1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Officer A, de la Fuente-Núñez V. A global campaign to combat ageism. Bull World Health Organ 2018; 96: 295–296. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.202424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 1000–1025. doi: 10.1177/0269216314526272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hattori A, Masuda Y, Fetters MD. A qualitative exploration of elderly patients’ preferences for end-of-life care. Japan Med Assoc J 2005; 48: 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandar M, Brockstein B, Zunamon A. Perspectives of health-care providers toward advance care planning in patients with advanced cancer and congestive heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017; 34: 423–429. doi: 10.1177/1049909116636614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard M, Bernard C, Tan A. Advance care planning: let’s start sooner. Can Fam Physician 2015; 61: 663–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 2014; 14: 219. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med 2011; 86: 996–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobbs D, Baker T, Carrion IV. Certified nursing assistants’ perspectives of nursing home residents’ pain experience: communication patterns, cultural context, and the role of empathy. Pain Manag Nurs 2014; 15: 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams J, Stickley T. Empathy and nurse education. Nurse Educ Today 2010; 30: 752–755. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa V, Earle CC, Esplen MJ. The determinants of home and nursing home death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0077-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirakawa Y, Kuzuya M, Uemura K. Opinion survey of nursing or caring staff at long-term care facilities about end-of-life care provision and staff education. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009; 49: 43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayser-Jones J. The experience of dying: an ethnographic nursing home study. Gerontologist 2002; 42: 11–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeda I, Miyashita M, Yamagishi A. Changes in relatives’ perspectives on quality of death, quality of care, pain relief, and caregiving burden before and after a region-based palliative care intervention. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52: 637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omar Daw Hussin E, Wong LP, Chong MC. Nurses’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators and their associations with the quality of end-of-life care. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: e688–e702. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klarare A, Hagelin CL, Fürst CJ. Team interactions in specialized palliative care teams: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 1062–1069. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YH, Ahn D, Moon J. Perception of interprofessional conflicts and interprofessional education by doctors and nurses. Korean J Med Educ 2014; 26: 257–264. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2014.26.4.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lidskog M, Löfmark A, Ahlström G. Learning about each other: students’ conceptions before and after interprofessional education on a training ward. J Interprof Care 2008; 22: 521–533. doi: 10.1080/13561820802168471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adachi M. Principles of health education and promotion by Dr. Tadao Miyasaka: a democratic approach and a change in the perspective of educational materials.

- 40.McKay KA, Narasimhan S. Bridging the gap between doctors and nurses. J Nurs Educ Pract 2012; 2: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schocken DM, Runyan A, Willieme A. Medical hierarchy and medical garb. Virtual Mentor 2013; 15: 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]