Dear Editor,

The benefit of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is debated [1–3]. Recent guidelines suggest use for most hypoxemic ARDS patients but no more than 48 h [3]. COVID-19 ARDS appears different from classical ARDS [4], and we aimed to describe the use of NMBA and analyze their association with day 28 outcome, in a multicentric observational prospective study (21 ICUs from Belgium and France).

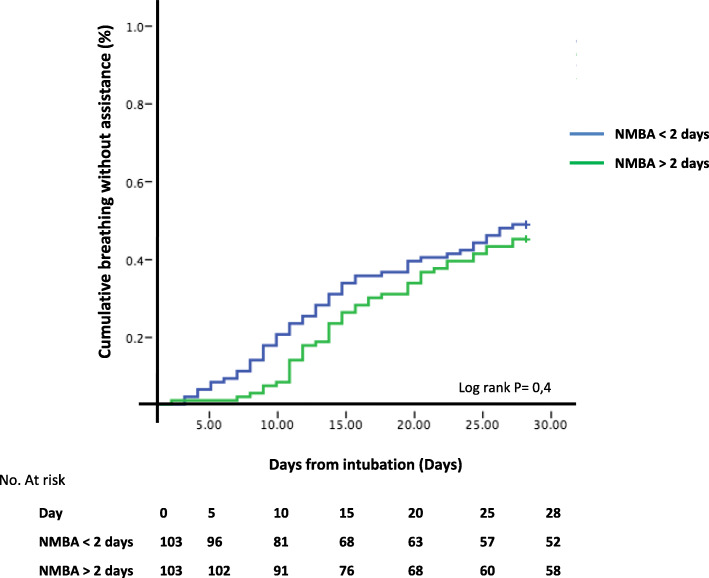

We enrolled consecutive patients with COVID-19 moderate to severe ARDS (Berlin definition) between 10 March and 15 April. The use of NMBA was defined as administration within 24 h after intubation and its duration as the length of continuous paralysis until 24 h of infusion cessation. Further administrations were not considered. Main indications for paralysis were prone positioning and hypoxemia (P/F < 150 mmHg). We dichotomized a priori the NMBA duration in less and more than 2 days. Patients without NMBA were considered to have 0 day of treatment. The primary endpoint was breathing without assistance at day 28. To account for difference between groups, we match the patients with short or long course of NMBA using a propensity score with 0.01 margin. We compared the time to extubation using the Kaplan-Meier curve and log rank test.

Four hundred seven patients with day 28 follow-up were included (Table 1). Among 342 patients (84%) who received NMBA (median duration 5 [IQR 2–10] days), 241 received it for more than 2 days. These latter had higher plateau pressure and rate of prone position and were more frequently in French ICUs. After propensity score matching of 206 patients, the rate and time to breathing without assistance at day 28 did not significantly differ between groups (Table 1 and Fig. 1). This was also the case in the subgroup of more hypoxemic (P/F < 120 mmHg) patients (n = 76) and in those with the lowest compliance (< 37 mL/cmH2O). Mechanical ventilation tended to be longer in survivors with long NMBA administration.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and outcome of the study cohort and after propensity score matching

| Study cohort | Propensity score matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 2d N = 166 | > 2d N = 241 | P* value | ≤ 2d N = 103 | > 2d N = 103 | P* value | |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 63 (56–71) | 65 (55–72) | 0.6 | 62 (56–70) | 63 (55–72) | 0.31 |

| Gender, male,n(%) | 123 (74) | 191 (79) | 0.23 | 71 (68) | 82 (79) | 0.11 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 29 (26–32) | 29 (26–33) | 0.16 | 29 (27–33) | 29 (26–32) | 0.24 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease,n(%) | 25 (15) | 33 (13) | 0.77 | 14 (0.13) | 11 (0.10) | 0.67 |

| Charlson score,n(%) | ||||||

| 0 | 72 (43) | 98 (41) | 0.97 | 43 (41) | 43 (41) | 0.93 |

| 1 | 37 (22) | 66 (27) | 28 (27) | 27 (26) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 57 (34) | 77 (32) | 32 (31) | 33 (32) | ||

| Country (France),n(%) | 81 (48) | 207 (85) | < 0.001 | 68 (66) | 85 (82) | 0.49 |

| Duration of symptoms, days median (IQR) | 7 (3–9) | 7 (4–9) | 0.35 | 7 (5–9) | 8 (5–10) | 0.70 |

| Respiratory values at baseline | ||||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, median (IQR) | 126 (88–162) | 120 (87–157) | 0.15 | 124 (87–154) | 120 (81–154) | 0.47 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 120 mmHg,n(%) | 55 (33) | 78 (32) | 0.87 | 37 (35) | 39 (37) | 0.77 |

| Plateau pressure (cmH20), median (IQR) | 23 (20–26) | 24 (21–26) | 0.07 | 23 (21–25) | 24 (21–26) | 0.9 |

| Peep (cmH20), median (IQR) | 12 (10–14) | 11 (10–13) | 0.38 | 12 (10–14) | 12 (10–13) | 0.32 |

| Tidal volume, (mL/kg of IBW), median (IQR) | 6.1 (5.8–6.8) | 6.1 (5.8–6.6) | 0.30 | 6.2 (5.8–6.8) | 6.1 (5.8–6.7) | 0.26 |

| Driving pressure (cmH20), median (IQR) | 11 (9–13) | 12 (10–14) | 0.07 | 11 (9–13) | 11 (9–14) | 0.91 |

| Compliance of respiratory system (mL/cmH2O) median IQR | 36.7 (30.7–44.4) | 34.6 (27.7–45) | 0.14 | 36.7 (30.2–40.3) | 36.8 (28.4–46.7) | 0.92 |

| Prone position,n(%) | 108 (65) | 217 (90) | < 0.001 | 80 (78) | 82 (80) | 0.86 |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Breathing without assistance at day 28, n (%) | 81 (49) | 93 (38) | 0.04 | 49 (47) | 45 (43) | 0.67 |

| d14 ventilatory mode | ||||||

| Death | 41 (25) | 94 (39) | 0.001 | 26 (25) | 35 (34) | 0.36 |

| Controlled mode—ECMO | 32 (19) | 55 (23) | 24 (23) | 22 (21) | ||

| Pressure support | 50 (30) | 41 (17) | 30 (29) | 21 (20) | ||

| Extubated | 42 (25) | 51 (21) | 23 (22) | 25 (24) | ||

| Needs for ECMO,n(%) | 14 (8) | 31 (13) | 0.2 | 11 (11) | 16 (15) | 0.4 |

| d28 VFDs, median (IQR) | 0 (0–16) | 0 (0–10) | 0.005 | 0 (0–15.5) | 0 (0–12.5) | 0.25 |

| ICU mortality | 62 (38) | 98 (41) | 0.54 | 39 (38) | 41 (42) | 0.67 |

| Length of MV in ICU survivors, median (IQR) | 15 (9–26) | 20 (13–32) | 0.003 | 15 (9–27) | 20 (13–31) | 0.09 |

| Hospital LOS** in ICU survivors, median (IQR) | 30 (20–50) | 36 (24–56) | 0.07 | 31 (20–50) | 38 (27–52) | 0.13 |

IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation, VFD ventilatory-free days

*P values were obtained from the Fisher test, t test, or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate

**Censured at day 90

Fig. 1.

Cumulative proportion of patients breathing without assistance in the two neuromuscular blocker agents (NMBA) groups using Kaplan-Meir curves. Comparison with log rank test

No other secondary outcomes appeared significantly different in this analysis.

In this multicentric study, NMBA were largely used for a longer duration than recommended. In a monocentric study, 60% of 267 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients received paralysis [5], whereas in the LUNGSAFE study [6], only 26% of ARDS patients receive NMBA. The massive use of NMBA in the context of shortage during COVID-19 crisis may be questionable. After adjustment for confounders, we did not observe a difference in the proportion of extubation rate according to NMBA length.

The high compliance of COVID-19 ARDS should protect them from barotrauma [4], one of the protective effects of NMBA [2]. However, respiratory drive appears high in these patients and patient self-induced lung injury (P-SILI) may occur, which may explain why investigators administered NMBA. We observed a low plateau pressure in our study but have no data about potential P-SILI.

One can be surprised to observe that matched on severity, time to extubation at day 28 was similar between patients with short or long course of NMBA. Our results indicate an equipoise regarding the duration of NMBA, which should be tested in proper trials.

Our study has limitations. Confounding and indication biases may exist despite adjustment, which decreased the study power. We did not collect the reason for NMBA continuing; they may have been prolonged in patients with the worst evolution. Finally, we did not gather the use of light sedation [1] and the occurrence of ICU-acquired weakness and diaphragm paresis, suggested by the trend to higher length of ventilation in the survivors.

In conclusion, we observed a large and prolonged use of NMBA in COVID-19 ARDS.

After adjustment, a prolonged course of NMBA was not associated with a lower rate of extubation at day 28.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank JB Mesland for the language revision of the manuscript.

We would like to thank all the participants of the COVADIS study for their efforts in collecting the information used in this study:

Dr. Nadia Aissaoui, Medecine Intensive Reanimation, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris France.

Dr. Giuseppe Carbutti, Unité de soins intensifs, CHR Mons-Hainaut, Mons, Belgium.

Dr. Alain D’hondt, Unité de soins intensifs, CHU Ambroise Paré, Mons, Belgium.

Dr. Julien Higny Unité de soins intensifs, CHU Dinant Godinne, site Dinant, Belgium.

Dr. Geoffrey Horlait Unité de soins intensifs, CHU Dinant Godinne, site Godinne, Belgium.

Dr. Sami Hraiech Médecine Intensive Réanimation, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Marseille, Hôpital Nord, Marseille, France.

Dr. Laurent Lefebvre Réanimation polyvalente Centre Hospitalier du pays d’Aix, Aix en Provence, France.

Dr. Francois Lejeune Unité de soins intensifs, Clinique Notre Dame de Grâce, Gosselies, Belgium.

Dr. Andre Ly Service d’anesthésie-réanimation chirurgicale Unité de réanimation chirurgicale polyvalente Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor, Créteil, France.

Dr. Michael Piagnerelli Intensive Care. CHU-Charleroi, Marie Curie. Charleroi, Belgium.

Dr. Bertrand Sauneuf Réanimation - Médecine Intensive, Centre Hospitalier Public du Cotentin, Cherbourg-en-Cotentin, France.

Dr. Thibaud SoumagneMédecine Intensive Réanimation, CHU Besançon, France.

Dr. Piotr Szychowiak Médecine Intensive Réanimation, CHRU Tours, France.

Dr. Julien Textoris Service de réanimation, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France.

Dr. Benoit Vandenbunder Groupe des anesthésistes réanimateurs, Hôpital Privé d’Antony, France.

Dr. Christophe Vinsonneau Service de Médecine Intensive Réanimation Centre Hospitalier de BETHUNE, Beuvry, France.

Authors’ contributions

Responsible for the study concept and design: Grimaldi D. and Lascarroou JB.; analysis and interpretation of the data: Grimaldi D., Lascarrou JB., and Courcelle R.; drafting of the manuscript: Grimaldi D., Courcelle R., and Serck N.; interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Grimaldi D., Courcelle R., Serck N. Gaudry S., and Lascarrou JB.; acquisition of the data: Grimaldi D., Blonz G., Courcelle R., Gaudry S., Serck N., and Lascarrou JB. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Availability of data and materials

D. Grimaldi and JB. Lascarrou had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The database will be public within 3 months after publication at https://icucovadis.com

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by appropriate regulatory committee in France (CNIL 2217488) and in Belgium (EC n°P2020/253) in accordance with the national regulation. Each patient was informed about the study. In case of incompetency, the next of kin were informed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David Grimaldi, Email: david.grimaldi@erasme.ulb.ac.be.

on behalf the COVADIS study group, Email: icucovadis@gmail.com.

on behalf the COVADIS study group:

Nadia Aissaoui, Giuseppe Carbutti, Alain D’hondt, Julien Higny, Geoffrey Horlait, Sami Hraiech, Laurent Lefebvre, Francois Lejeune, Andre Ly, Michael Piagnerelli, Bertrand Sauneuf, Thibaud Soumagne, Piotr Szychowiak, Julien Textoris, Benoit Vandenbunder, and Christophe Vinsonneau

References

- 1.National Heart L, Blood Institute PCTN. Moss M, Huang DT, Brower RG, Ferguson ND, et al. Early neuromuscular blockade in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):1997–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, et al. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papazian L, Aubron C, Brochard L, et al. Formal guidelines: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensive Care. 2019;9:69. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0540-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care. 2020;24:154. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edward J, Schenck KH, Goyal P, et al. Respiratory mechanics and gas exchange in COVID-19 associated respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-427RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.LUNG SAFE investigators Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

D. Grimaldi and JB. Lascarrou had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The database will be public within 3 months after publication at https://icucovadis.com