Introduction

Solid persistent facial edema is a rare and poorly understood condition that is difficult to treat and can lead to significant cosmetic disfigurement, adversely affecting a patient's self-esteem and mental health.1 It can be a serious complication of acne vulgaris and rosacea, but also may be associated with other congenital, infectious, malignant, and inflammatory processes.2 It has also been referred to as Morbihan's disease (referring to the French district where it was first described in 1957) and rosaceous lymphedema.3, 4, 5

The pathogenesis of solid persistent facial edema and definitive treatment remain unclear. Theories have suggested that Morbihan's disease is an end-stage complication of rosacea and acne.4 The recurrent occurrences of vascular dilation and inflammation may lead to chronic inflammatory changes, including damage and remodeling of the vascular and lymphatic vessels.4 Persistent edema results from impaired lymphatic drainage. However, Morbihan's disease has occurred in patients without rosacea, or as a first symptom of rosacea.4 Therefore, it is possible that solid persistent facial edema may represent a separate disease entity. Herein, we describe a patient who presented with solid persistent facial edema and responded well to isotretinoin and compression therapy.

Case report

A 24-year-old white man with no history of significant acne vulgaris, rosacea, or visual complaints presented with an 8-month history of persistent left periorbital swelling. He had previously been evaluated by multiple physicians, including an allergist and ophthalmologist, without a definitive diagnosis or response to treatment with corticosteroid ophthalmic solutions or oral antihistamines.

Physical examination revealed non-erythematous, non-pitting edema of the left periorbital aspect of the face, with no conjunctival inflammation (Fig 1). He received a diagnosis of “persistent localized edema,” and was treated with a combination of loratadine, cetirizine, and doxepin. Subsequent evaluation included paranasal radiography and maxillofacial computed tomography scan, revealing only periorbital soft tissue swelling, negative result for North American Standard Series patch testing, a negative tuberculin skin test result, and histology showing numerous dermal ectatic blood vessels and lymphatics and a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Solid persistent facial edema before treatment with isotretinoin.

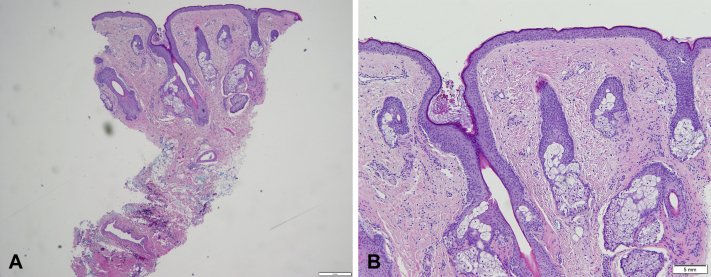

Fig 2.

A and B, Solid persistent facial edema histology showing numerous dermal ectatic blood vessels and lymphatics and a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes.

A diagnosis of solid persistent facial edema was made, and after a 2-month course of doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) and antihistamine therapy did not result in improvement, these medications were discontinued, with the addition of isotretinoin 40 mg/day because of patient frustration and desire for alternate therapy. After 3 months of therapy with isotretinoin, there was mild clinical improvement, and night compression therapy was initiated, consisting of a full facial plastic mask with elastic compression straps produced by a physical therapy clinic. Within 2 months, there was significant clinical improvement, and the isotretinoin dose was decreased to 40 mg every other day. Sustained clinical improvement was achieved during the subsequent 15 months (Fig 3), at which time isotretinoin was discontinued, and clinical improvement has been maintained with continued night compression therapy alone.

Fig 3.

Solid persistent facial edema 5 months after initiation of isotretinoin and 2 months after initiation of compression therapy.

Discussion

Patients with solid persistent facial edema often have a history of acne or another skin condition that was present 2 to 5 years before the development of facial edema.6 Clinically, there is characteristic firm, non-pitting edema and erythema of the centrofacial and periorbital area, including the forehead, glabella, eyelids, nose, and cheeks.4,5 Initially, the edema may be pitting, but subsequently may become firm, non-pitting edema as a result of chronic inflammation and fibrosis.4

It is thought that chronic inflammation may lead to lymphatic stasis, as well as an imbalance between the production and drainage of lymphatic fluid.1,5, 6, 7 Mast cells within the inflammatory infiltrate may contribute to fibrosis.1,6 Histopathologic findings of patients with solid persistent facial edema have included dermal edema, dilated lymphatic and blood vessels, lymphohistiocytic perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate, and several mast cells within the thickened and fibrotic dermis.1,3,4,6, 7, 8 The differential diagnoses of solid persistent facial edema include Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, as well as lupus erythematosus, contact dermatitis, chronic actinic dermatitis, sarcoidosis, dermatomyositis, erysipelas, mycobacterium infections, thyroid disease, and lymphoma.5,6,9

Complications of solid persistent facial edema include deformity that may lead to visual obstruction, constant tearing from the affected eye, functional problems, and diminished self-esteem as a result of cosmetic disfigurement.3,4 Patients often have no other symptoms other than deformity.

Solid persistent facial edema represents a treatment challenge. Treatments used for this condition have included isotretinoin, antihistamines, corticosteroids, antibiotics, interferon gamma, thalidomide, lymphatic massage, compression garments, radiation, and surgical management (including blepharoplasties, lymphatic drainage surgeries, carbon dioxide lasers, and local steroid injections), with varying degrees of response.3, 4, 5 However, treatment options, including surgical intervention, often provide only partial or temporary treatment response.4 Boparai et al4 found that longer periods of antibiotic management correlated with response to treatment and stated that patents may benefit from a 4- to 6-month duration of tetracycline-based antibiotics. However, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, and combinations of therapies did not correspond to treatment response.

Other studies suggest that isotretinoin is the most effective treatment option when it is used as a sole agent or in combination with others.2,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Welsch and Schaller7 found a significant reduction in erythema and edema in 4 patients managed with ultralow-dose isotretinoin and antihistamines with a mean duration of 14 months. Olvera-Cortés and Pulido-Díaz9 described 3 patients successfully treated with high-dose, long-term isotretinoin. Smith and Cohen5 described 5 patients with Morbihan's disease who experienced substantial clinical improvement, although this was not noted until after 6 months of treatment. There may be specific subtypes of solid persistent facial edema that are more responsive to isotretinoin than antibiotics, which may account for discrepancies in the literature regarding the treatment response of isotretinoin for patients with Morbihan's disease.4

Isotretinoin seems to improve solid persistent facial edema through its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.1,2,5,7,9 It also plays a role in the repair of structural tissue damage, as well as inhibitory effects on fibroblast proliferation.5,9 Both isotretinoin and clofazimine stimulate macrophage function and phagocytosis.10

Medical management has been more effective when used early in the course of the disease, before the development of fibrosis and permanent edema.1 The use of isotretinoin to decrease the acne initially, followed by lymph massage to decrease the remaining edema, has led to clinical improvement.10

The etiology of solid persistent facial edema is poorly understood. Although its presence in this patient may precede the development of an associated condition, the lack of history of significant acne vulgaris, young age, and lack of associated symptoms are unique and give credence to the possibility it is a separate disease entity apart from inflammatory skin conditions in some patients.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Kilinc I., Gencoglan G., Inanir I., Dereli T. Solid facial edema of acne: failure of treatment with isotretinoin. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(5):503–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman S.J., Fox B.J., Albert H.L. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris: treatment with isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(2):286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechara F.G., Jansen T., Losch R., Altmeyer P., Hoffmann K. Morbihan's disease: treatment with CO2 laser blepharoplasty. J Dermatol. 2004;31(2):113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boparai R.S., Levin A.M., Lelli G.J., Jr. Morbihan disease treatment: two case reports and a systematic literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(2):126–132. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith L.A., Cohen D.E. Successful long-term use of oral isotretinoin for the management of Morbihan disease: a case series report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(12):1395–1398. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jungfer B., Jansen T., Przybilla B., Plewig G. Solid persistent facial edema of acne: successful treatment with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Dermatology. 1993;187(1):34–37. doi: 10.1159/000247194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welsch K., Schaller M. Combination of ultra-low-dose isotretinoin and antihistamines in treating Morbihan disease - a new long-term approach with excellent results and a minimum of side effects. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1721417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzatenta C., Giorgino G., Rubegni P., Aloe G.D., Fimiani M. Solid persistent facial oedema (Morbihan's disease) following rosacea, successfully treated with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):1020–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olvera-Cortés V., Pulido-Díaz N. Effective treatment of Morbihan's disease with long-term isotretinoin: a report of three cases. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):32–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helander I., Aho H.J. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris: treatment with isotretinoin and clofazimine. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67(6):535–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]