Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) disease (COVID-19) is characterized by severe pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome in about 20% of infected patients. Computed tomography (CT) is the routine imaging technique for diagnosis and monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia. Chest CT has high sensitivity for diagnosis of COVID-19, but is not universally available, requires an infected or unstable patient to be moved to the radiology unit with potential exposure of several people, necessitates proper sanification of the CT room after use and is underutilized in children and pregnant women because of concerns over radiation exposure. The increasing frequency of confirmed COVID-19 cases is striking, and new sensitive diagnostic tools are needed to guide clinical practice. Lung ultrasound (LUS) is an emerging non-invasive bedside technique that is used to diagnose interstitial lung syndrome through evaluation and quantitation of the number of B-lines, pleural irregularities and nodules or consolidations. In patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, LUS reveals a typical pattern of diffuse interstitial lung syndrome, characterized by multiple or confluent bilateral B-lines with spared areas, thickening of the pleural line with pleural line irregularity and peripheral consolidations. LUS has been found to be a promising tool for the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia, and LUS findings correlate fairly with those of chest CT scan. Compared with CT, LUS has several other advantages, such as lack of exposure to radiation, bedside repeatability during follow-up, low cost and easier application in low-resource settings. Consequently, LUS may decrease utilization of conventional diagnostic imaging resources (CT scan and chest X-ray). LUS may help in early diagnosis, therapeutic decisions and follow-up monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia, particularly in the critical care setting and in pregnant women, children and patients in areas with high rates of community transmission.

Key Words: Lung ultrasound, COVID-19, Pneumonia, Interstitial syndrome, B-Lines, Acute respiratory disease syndrome

Introduction

The novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) hit the central regions of China in late December 2019 and subsequently spread rapidly to multiple countries worldwide. A pandemic outbreak of this virus with rapid human-to-human transmission constituted a dire public health emergency.

SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) is characterized by severe pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in about 20% of infected patients (Chen et al. 2020a; Huang et al. 2020a), with high morbidity and mortality. Herein, we provide an overview of the role of lung ultrasound (LUS) in the early diagnosis, therapeutic decision-making process and follow-up monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia, representing a reliable alternative to computed tomography (CT) in this setting. Cited retrospective and prospective human studies had institutional review board (IRB) approval. Publications without IRB approval are in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Role of CT in COVID-19 pneumonia

Chest CT is considered the routine imaging technique for diagnosis and monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia have characteristic CT features: ground-glass or fine reticular opacities, reticulation, subpleural consolidations, vascular thickening and/or traction bronchiectasis, with peripheral distribution, bilateral involvement, lower lung predominance and multifocal distribution (Bai et al. 2020; Chung et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2020).

Chest CT has high specificity (Bai et al. 2020) and high sensitivity in the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia, being helpful in early screening of both symptomatic and asymptomatic highly suspected cases (Chen et al. 2020a; Shi et al. 2020) and in patients before negative-to-positive conversion of the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Ai et al. 2020; Xie et al. 2020). However, in different studies, 20 of 36 (56%) positive adult patients in the first 2 d after clinical onset (Bernheim et al. 2020), 8 of 99 (8%) symptomatic adult patients with history of exposure to confirmed cases (Zhao et al. 2020) and 12 of 24 (50%) asymptomatic positive carriers (Hu et al. 2020) had no abnormal CT findings.

Moreover, CT scan is not universally available in emergency departments and is a suboptimal option in the pediatric setting because of the exposure to high-dose radiation and the frequent need for sedation (Miglioretti et al. 2013). Furthermore, in a recent systematic review including 4612 children with COVID-19, 85.7% underwent chest CT scan, and 36% of them had no pathologic CT findings (Liguoro et al. 2020).

The increasing frequency of confirmed COVID-19 cases is striking, and new highly sensitive diagnostic tools are needed in clinical practice. This is particularly true considering that most of the affected/contagious patients are asymptomatic or experience mild symptoms (Li et al. 2020), RT-PCR has a sensitivity of only 71% for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fang et al. 2020) and a considerable proportion of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have normal chest radiographs at onset (Ng et al. 2020; Yoon et al. 2020).

LUS: Basics, scoring systems and technical aspects

Several data have indicated that LUS is an emerging non-invasive bedside technique in the diagnosis of interstitial lung syndrome because it is used to evaluate and quantify the number of B-lines, pleural irregularities and nodules or consolidations (Volpicelli et al. 2012; Soldati and Demi 2017; Demi et al. 2020a). LUS reveals numerous artifacts that physicians recognize and evaluate as part of their diagnosis (Demi et al. 2020b):

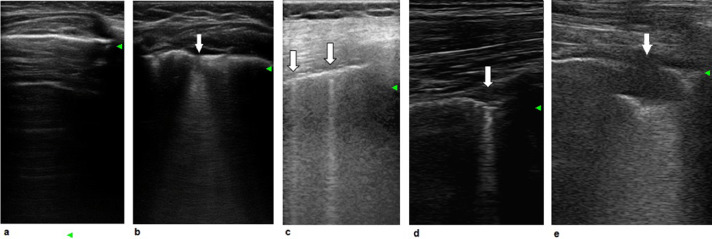

A-Lines are motionless and regularly spaced lines horizontal to the pleura (Fig. 1 a), and correspond to normal reverberation artifacts of the pleural line.

Fig. 1.

(a) A-Lines: Lines horizontal to the pleura. (b–e). B-Lines: Linear vertical artifacts that arise from pleural lines (a) with different B-line shapes, for example, a single cone-shaped line (b), a single thin line (c), a single thick line (d) and a subpleural consolidation without air bronchogram (e).

B-Lines are vertical linear artifacts that arise from pleural lines (Fig. 1 a), likely representing ultrasound reverberations generated by the thickened interlobular septa and other subpleural structures (Volpicelli et al. 2012). There are several different B-line shapes, for example, the single cone-shaped line (Fig. 1b), single thin line (Fig. 1c) and single thick line (Fig. 1d).

Multiple B-lines are considered the sonographic sign of lung interstitial syndrome, and their number increases along with decreasing air content and increasing lung density. An inhomogeneous bilateral pattern of multiple coalescent B-lines and white lung, sometimes with scattered spared areas, characterizes ARDS (Soldati and Demi 2017).

Lung peripheral consolidations are subpleural echo-poor regions or regions with tissue-like echotexture (Fig. 1e), with different features: with or without air or fluid bronchogram, vertical artifacts at the far-field margin or hepatization (Volpicelli et al. 2012). Consolidations associated with B-lines are characteristic ultrasound patterns observed in patients with ARDS.

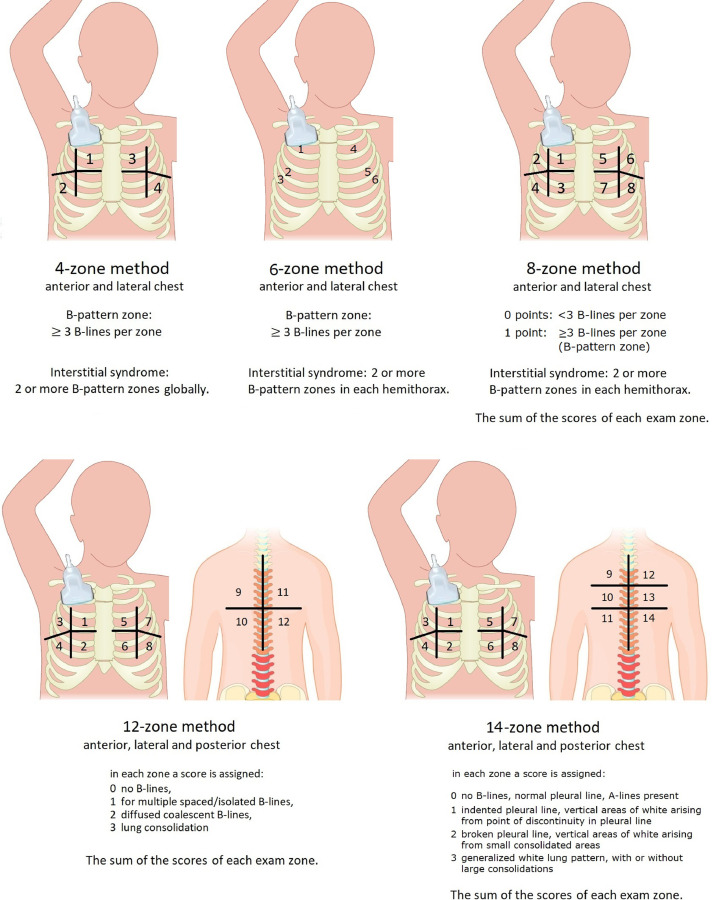

In clinical practice, especially in the critical care setting, several scoring systems have been proposed to quantify the extent of lung involvement, based on the number of chest wall zones used in each system: the 4-zone, 6-zone, 8-zone, 12-zone and 14-zone methods (Fig. 2 ) are adopted mainly in critical care settings. With the 4-, 6- or 8-zone scoring system (Platz et al. 2019), B-lines are counted in multiple intercostal spaces across the thorax, and the presence of three or more B-lines in a single intercostal space is defined as the “B-pattern.” Differently, with the 12-zone scoring system, in each zone a score of 0 is assigned for no B-lines and a score of 1 is assigned for multiple spaced/isolated B-lines, a score of 2 is assigned for diffused coalescent B-lines or “light beam” and a score of 3 is assigned for lung consolidation (Volpicelli et al. 2020). Finally, in the 14-zone scoring system, in each zone a score of 0 is assigned for regular pleural line and A-lines, a score of 1 is assigned for an indented pleural line with vertical areas of white below each indent, a score of 2 is assigned for a broken pleural line with vertical areas of white below each small-to-large consolidated area and a score of 3 is assigned for dense and largely extended white lung with or without larger consolidations (Soldati et al. 2020b).

Fig. 2.

Different scoring systems used to quantify the extent and characterize the different patterns of lung involvement.

Recently, an Italian consensus proposed a standardization for the international use of LUS in the management of patients with COVID-19 to use a well-validated terminology related to image artifacts and adopt objective clinical standards for interpretation of imaging features (Soldati et al. 2020b).

LUS scanning frequencies, technical adjustments, acquisition protocols, choice of different probes and mechanical indexes have strong effects on the visualization and counting of lung B-lines (Soldati et al. 2020b). Consequently, to avoid misdiagnosis, LUS should be used only by appropriately trained users.

Role of LUS in diagnosis of pneumonia

LUS has been reported to be a promising tool for the diagnosis and follow-up of pneumonia in adults as well as in children (Reissig and Copetti 2014; Pereda et al. 2015). In a meta-analysis, LUS exhibited high accuracy in diagnosing pneumonia compared with chest CT scan (Long et al. 2017). Moreover, in diagnostic performance in interstitial lung syndrome (interstitial pneumonia, interstitial diseases and ARDS), LUS is now considered to be similar to CT scan (Asano et al. 2018; Patel et al. 2018; Man et al. 2019; Mayo et al. 2019), which is the gold standard method for diagnosis. In particular, a comparative study by Lichtenstein et al. (2004) indicated that the accuracy of LUS in patients with ARDS was 93% for pleural effusion, 97% for consolidation and 95% for alveolar interstitial syndrome.

The specificity of B-line evaluation at LUS is, however, low because B-lines can be visualized in any disease process causing interstitial lung disease (e.g., mild to moderate lung congestion, pulmonary edema, pneumonitis, viral pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis, ARDS) (Dietrich et al. 2016; Soldati et al. 2019; Demi et al. 2020a). Similarly, subpleural consolidations and pleural effusion, which represent anatomic alterations and not artifacts, have low specificity for COVID-19 as they appear in many different conditions. Although the most frequent cause of interstitial pneumonia in areas with high COVID-19 prevalence is SARS‐CoV‐2, other causes remain possible (atypical bacteria, flu viruses, etc.).

Role of LUS in diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia

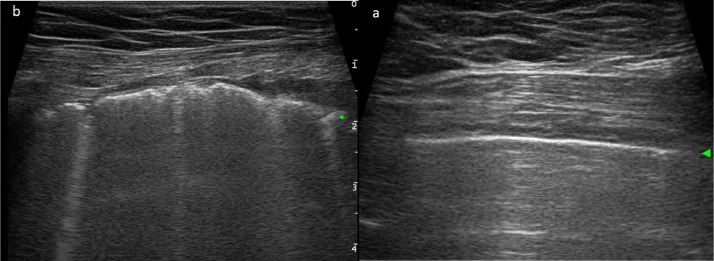

In patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, LUS reveals the typical bilateral pattern of diffuse interstitial lung syndrome, characterized by multiple or confluent B-lines with spared areas, thickening of the pleural line with pleural line irregularity (Fig. 3 ) and, less frequently, subpleural consolidations and pleural effusion (Buonsenso et al. 2020b; Huang et al. 2020b; Lomoro et al. 2020; Nouvenne et al. 2020; Poggiali et al. 2020a; Peng et al. 2020; Soldati et al. 2020a; Volpicelli and Gargani 2020; Volpicelli et al. 2020; Xing et al. 2020; Yasukawa and Minami 2020).

Fig. 3.

Ultrasonographic features of normal lung and COVID-19 pneumonia. (a) Normal sonographic lung appearance. Pleural line (hyper-echoic horizontal line, green arrowhead) and multiple horizontal reverberations of the pleural line (A-lines). (b) Severe interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome sonographic appearance. Green arrowhead indicates irregular pleural line; vertical lines indicate multiple blurred B-lines.

This pattern was previously described for interstitial pneumonia caused by different etiologies, such as Chlamydia (Perrone and Quaglia 2017), Pneumocystis (Limonta et al. 2019), measles (Volpicelli and Frascisco 2009), influenza virus A H7N9 (Zhang et al. 2015) and influenza virus H1N1 (Testa et al. 2012; Tsung et al. 2012), supporting the role of LUS in the diagnosis of COVID-19. In COVID-19 pneumonia, different degrees of interstitial syndrome and alveolar consolidation detected by LUS are directly correlated with the severity of the lung injury (Peng et al. 2020; Xing et al. 2020).

There are currently no known findings pathognomonic of COVID-19 on LUS, although Volpicelli et al. recently reported the “light beam,” a broad, lucent, band-shaped, vertical artifact that moves rapidly with sliding, corresponding to the early appearance of “ground glass” (Volpicelli and Gargani 2020; Volpicelli et al. 2020).

LUS can detect the pulmonary dynamic changes associated with COVID-19 pneumonia (Soldati et al. 2020a). In the early stages, the main ultrasound finding is focal B-lines, while, as the disease progresses, B-lines become multifocal and confluent (interstitial lung syndrome), with further development of clear consolidations (Fiala 2020; Soldati et al. 2020b). During convalescence, B-lines and consolidations gradually disappear and are replaced by A-lines (Denina et al. 2020; Peng et al. 2020; Xing et al. 2020).

In this setting, the findings on LUS appear to correlate well with the findings on chest CT scan in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (Huang et al. 2020b; Lu et al. 2020a; Peng et al. 2020; Poggiali et al. 2020a; Yang et al. 2020b) and can be expected to develop over a similar timeline (Fiala 2020).

The sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of LUS have been reported to increase with the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia compared with chest CT scan (Lu et al. 2020).

LUS allows for the evaluation of pleural and peripheral pulmonary lesions, while cannot detect lesions that are deep within the lung, as aerated lung blocks the transmission of ultrasound. However, studies on chest CT in patients with COVID-19 have revealed that most of the consolidations are generally localized in the peripheral lung (Liu et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020a, 2020b), which facilitates detection by LUS.

Of note, in a comparative study with chest CT scan, LUS had lower specificity in differentiating patients with COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pneumonia (Chen et al. 2020b), considering that different pathogens can share similar LUS patterns. However, through rational integration of LUS with the clinical data, good specificity can be achieved in cases of LUS findings suggestive of COVID-19, in relatively young patients or in those without a history of lung disease, in the not‐very‐early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia (Soldati et al. 2020c).

Compared with CT, LUS has several advantages: It enables bedside assessment, reduces the length of patient stay in the emergency room (reducing health care workers’ exposure to infected patients), prevents exposure to radiation (especially for children and pregnant women), can be repeated during follow-up at low cost and is easily applied in low-resource settings (Volpicelli et al. 2012; Soldati and Demi 2017; Buonsenso et al. 2020a; Denina et al. 2020; Moro et al. 2020). Moreover, CT scan requires transport of the patient, potentially infected and unstable, to the radiology unit with potential exposure of several people, and necessitates proper sanification of the CT room after use.

LUS can guide therapeutic decisions and procedures in different settings

The use of bedside LUS allows integration of the information on the state of the lung (sonographic patterns) with all the information from medical history, risk of exposure, clinical examination and blood exams, giving the physician a better characterization of the disease and helping in the decision-making process (Volpicelli et al. 2020). This multiparametric approach may increase the diagnostic accuracy of LUS for COVID-19 pneumonia, especially in mild to moderate disease or in differential diagnoses with non-COVID-19 pneumonia, for which LUS seems to have lower specificity compared with CT scan (Chen et al. 2020b; Lu et al. 2020a).

Although conclusive data on COVID-19 patients are still lacking, data from studies in different settings of interstitial pneumonia and ARDS may support the role of LUS, especially in areas with high rates of community transmission, guiding therapeutic decisions and procedures in patients with COVID-19 in many critical settings (Soldati et al. 2020b): general practitioners’ offices, nursing homes, emergency departments, general internal medicine wards, pulmonology wards, hemodialysis units, obstetrics and paediatrics.

Those general practitioners who are confident using LUS may represent a first important step for patients clinically suspected of having COVID-19 infection, reducing unnecessary emergency department visits. LUS might provide an additional datapoint to the full clinical picture, especially if compared with the limited traditional chest auscultation (Copetti 2016), and allow advanced triage for COVID-19 directly at home (Shokoohi et al. 2020; Soldati et al. 2020c). The probe can be used as a stethoscope to scan any portion of the lung, providing increased diagnostic accuracy.

Nursing homes are on the front lines of this pandemic, and their residents have been decimated in several countries worldwide. LUS, with a portable ultrasound device, has proven to be an excellent tool for identifying COVID-19 in nursing home residents (Nouvenne et al. 2020), suggesting a potential role for screening patients at high risk in a setting characterized by scarce diagnostic resources.

In emergency departments or in COVID-restricted triage areas for patients clinically suspected of having COVID-19 infection, use of LUS as a primary survey tool in acutely dyspneic or hypoxemic patients provides an immediate evaluation of the lung (Zanobetti et al. 2017; Volpicelli et al. 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, LUS, as part of a structured triage system in an emergency department, can help to detect pulmonary and pleural findings early, even in patients without respiratory symptoms and/or fever, especially if pulse oxygen levels are lower than normal values (Poggiali et al. 2020b). For a patient with respiratory failure, a normal LUS could rule out COVID-19 pneumonia and orient the examiner toward different diagnosis (Volpicelli et al. 2020). Conversely, we suggest that patients with LUS findings suggestive of COVID-19 but negative RT-PCR results should be isolated, and RT-PCR should be repeated to avoid misdiagnosis (Soldati et al. 2020c).

In general internal medicine wards and pulmonology wards, LUS might be useful for monitoring the effect of therapeutic drugs (immunosuppressive strategies, antiviral drugs or others) as a bedside and real-time technique, and may decrease utilization of conventional diagnostic imaging resources, reducing exposure of health care workers to SARS-CoV-2 (Yasukawa and Minami 2020).

Patients on hemodialysis are at increased risk of contagion and serious complications during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alberici et al. 2020), because of frequent contact with health care facilities and a high comorbidity burden. Although patients on dialysis have multiple potential etiologies for dyspnea and multiple B-lines at LUS (such as heart failure and fluid overload) and for fever (such as vascular access infection), different LUS patterns detected in COVID-19 patients may help in differential diagnosis in this setting (Reisinger and Koratala 2020; Vieira et al. 2020).

In pregnant woman, LUS may represent a valuable alternative to CT scan during the COVID-19 pandemic (Buonsenso et al. 2020a; Moro et al. 2020; Youssef et al. 2020), particularly because it is mandatory to avoid exposure to radiation in this specific setting, and obstetricians and gynecologists are usually familiar with the use of ultrasound.

In the pediatric setting, where LUS is considered as an imaging alternative to CT scan for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia (Pereda et al. 2015), LUS could play a central role in the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, LUS has been reported to be able to detect lung pathology in children (Denina et al. 2020; Musolino et al. 2020) and neonates (Feng et al. 2020) with confirmed COVID-19, even when asymptomatic, with the same LUS patterns described in adults. Moreover, LUS was found to decrease utilization of conventional diagnostic imaging resources in children with suspected COVID-19 (De Rose et al. 2020). The large number of asymptomatic and mild cases of COVID-19 in children (Lu et al. 2020b; Parri et al. 2020) confirms that chest CT scan and X-ray should not be routinely used. However, further studies in children are needed because LUS reveals conflicting results in early stages and mild forms of COVID-19 pneumonia (Musolino et al. 2020; Scheier et al. 2020).

Although the sensitivity and specificity of LUS in diagnosing COVID-19 pneumonia remain to be determined in larger studies, LUS represents a reliable alternative to CT scan and chest X-ray in all these settings.

Efficient triage of patients with suspected COVID-19 at all health facility levels can help the national response planning and case management system cope with patient influx.

LUS may guide therapeutic decisions and procedures in intensive care units

In hemodynamically or respiratory unstable patients in intensive care, LUS may have major utility in bedside management of COVID-19, to track the evolution of interstitial pneumonia and ARDS, to monitor lung recruitment maneuvers and response to therapies, to identify early possible complications (pneumothorax, over-infections), to guide several invasive procedures and to make decisions on weaning patients from ventilator support (Mojoli et al. 2020; Peng et al. 2020).

Although data on intensive care unit patients with COVID-19 are scarce, a practical approach based on LUS can be proposed to guide therapeutic decisions in ARDS patients (Bouhemad et al. 2015), and different LUS scoring systems may be used to estimate the extent of lung involvement (Volpicelli et al. 2020). In fact, a significant reduction in or absence of lung sliding and the evolution to consolidations indicate severe pneumonia or ARDS, suggesting that the patient may require invasive ventilatory support (Copetti et al. 2008; Reissig and Copetti 2014). Moreover, LUS score, as an estimate of lung aeration, can be regularly monitored at the beginning and at any time point after therapy for COVID-19 is started (i.e., positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] trial or prone position) (Conway et al. 2020). An increase in score and/or the presence of posterolateral/inferior consolidations indicate a decrease in aeration, suggesting the need for additional PEEP and recruitment maneuvers, while a decrease in score indicates re-aeration, suggesting the success of interventions and, eventually, weaning from respiratory support (Conway et al. 2020). To confirm this, although data on COVID-19 patients are still lacking, PEEP-induced lung recruitment (Lichtenstein et al. 2004; Bouhemad et al. 2011) and the response to prone positioning (Prat et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016) can be adequately estimated with bedside LUS in patients with ARDS.

LUS can be useful in confirming endotracheal tube placement (Das et al. 2015; Karacabey et al. 2016), which is particularly tricky in the COVID-19 area setting and when an end-tidal CO2 device is not available, and in detecting pneumothorax (Alrajab et al. 2013), which is frequently identified by an anterior extension in the critically ill patient in a recumbent or semirecumbent position.

Even if pleural effusions are not frequent in COVID-19 patients, bedside thoracentesis can be tolerably performed with an echo-guided technique, to promote lung recruitment and ameliorate oxygenation and to reduce the incidence of peri-procedural complications (Mercaldi et al. 2013; Rodriguez-Lima et al. 2020).

LUS seems to be a more tolerable and more convenient alternative to CT scans in a transportation-limited setting such as mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In an urgent situation, such as a patient's sudden deterioration, a quick imaging tool is greatly needed.

In this setting, systematic application of LUS has been reported to decrease utilization of conventional diagnostic imaging resources (Pontet et al. 2019; Mojoli et al. 2020; Mongodi et al. 2020; Vetrugno et al. 2020).

Recommendations for LUS to prevent SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission

Personal protective equipment should be worn when scanning a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. To minimize the risk of potential SARS-CoV-2 transmission, sonographers (i) should assume that every patient has COVID-19 infection; (ii) should wear personal protective equipment, such as face masks (N95/FFP2 or FFP3), waterproof protective gear or goggles, a disposable gown and one or two pairs of disposable gloves (World Health Organization [WHO] 2020); (iii) should drape the ultrasound machine with a plastic disposable wrap, covering probes, cables, couch and keyboard with disposable covers; and (iv) should clean and disinfect the equipment and room with alcohol-based disinfectant cleaner at the end of every exam.

Compared with a portable X-ray or CT machine, ultrasound machines are faster to decontaminate because of their small size. Some physicians have reduced the risk of COVID-19 transmission and minimized decontamination time by using portable, hand-held wireless ultrasound probes attached to sheathed tablet devices, placed in two separate single-use plastic covers (Buonsenso et al. 2020b). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, portable ultrasound is valuable because it can be transported to remote areas and can be easily sterilized.

LUS should, however, be used only by appropriately trained users, to avoid misdiagnosis and prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission resulting from non-adherence to appropriate cleaning and disinfection principles.

Conclusions

LUS may be a first-line diagnostic imaging alternative to chest CT scan and chest X-ray during every step of COVID-19 disease, even before clinical manifestations, particularly in children, pregnant women, critically ill patients that cannot be moved and patients in areas with high rates of community transmission. The combination of sonographic patterns at LUS with clinical and laboratory findings, followed by chest CT for confirmation in selected cases, may help in early diagnosis, therapeutic decisions and follow-up monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia in both children and adults.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Luigi Rolli for his help and support.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest disclosure

Dr. Allinovi, Dr. Parise, Dr. Giacalone, Prof. Amerio, Dr. Delsante, Prof. Odone, Dr. Gigliotti, Dr. Franci, Dr. Amadasi, Prof. Delmonte, Dr. Parri, and Dr. Mangia report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., Zhan C., Chen C., Lv W., Tao Q., Sun Z., Xia L. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020;26 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberici F., Delbarba E., Manenti C., Econimo L., Valerio F., Pola A., Maffei C., Possenti S., Piva S., Latronico N., Focà E., Castelli F., Gaggia P., Movilli E., Bove S., Malberti F., Farina M., Bracchi M., Costantino E.M., Bossini N., Gaggiotti M., Scolari F., Brescia Renal COVID Task Force Management of patients on dialysis and with kidney transplant during SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in Brescia, Italy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:580–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alrajab S., Youssef A.M., Akkus N.I., Caldito G. Pleural ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax: Review of the literature and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R208. doi: 10.1186/cc13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M., Watanabe H., Sato K., Okuda Y., Sakamoto S., Hasegawa Y., Sudo K., Takeda M., Sano M., Kibira S., Ito H. Validity of ultrasound lung comets for assessment of the severity of interstitial pneumonia. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:1523–1531. doi: 10.1002/jum.14497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H.X., Hsieh B., Xiong Z., Halsey K., Choi J.W., Tran T.M.L., Pan I., Shi L.B., Wang D.C., Mei J., Jiang X.L., Zeng Q.H., Egglin T.K., Hu P.F., Agarwal S., Xie F., Li S., Healey T., Atalay M.K., Liao W.H. Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT. Radiology. 2020;10 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim A., Mei X., Huang M., Yang Y., Fayad Z.A., Zhang N., Diao K., Lin B., Zhu X., Li K., Li S., Shan H., Jacobi A., Chung M. Chest CT findings in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19): Relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;20 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhemad B., Brisson H., Le-Guen M., Arbelot C., Lu Q., Rouby J.J. Bedside ultrasound assessment of positive end-expiratory pressure-induced lung recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:341–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0369OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhemad B., Mongodi S., Via G., Rouquette I. Ultrasound for “lung monitoring” of ventilated patients. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:437–447. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonsenso D., Raffaelli F., Tamburrini E., Biasucci D.G., Salvi S., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Scambia G., Lanzone A., Testa A.C., Moro F. Clinical role of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis and monitoring of COVID-19 pneumonia in pregnant women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:106–109. doi: 10.1002/uog.22055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonsenso D., Pata D., Chiaretti A. COVID-19 outbreak: Less stethoscope, more ultrasound. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30120-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Tang Y., Mo Y., Li S., Lin D., Yang Z., Yang Z., Sun H., Qiu J., Liao Y., Xiao J., Chen X., Wu X., Wu R., Dai Z. A diagnostic model for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based on radiological semantic and clinical features: A multi-center study. Eur Radiol. 2020;16:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X., Cui J., Xu W., Yang Y., Fayad Z.A., Jacobi A., Li K., Li S., Shan H. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;4 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway H., Lau G., Zochios V. Personalizing invasive mechanical ventilation strategies in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated lung injury: The utility of lung ultrasound. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copetti R. Is lung ultrasound the stethoscope of the new millennium? Definitely yes! Acta Med Acad. 2016;45:80–81. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copetti R., Soldati G., Copetti P. Chest sonography: A useful tool to differentiate acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema from acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.K., Choupoo N.S., Haldar R., Lahkar A. Transtracheal ultrasound for verification of endotracheal tube placement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0301-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rose C., Inchingolo R., Smargiassi A., Zampino G., Valentini P., Buonsenso D. How to perform pediatric lung ultrasound examinations in the time of COVID-19. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jum.15306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demi L., Egan T., Muller M. Lung ultrasound imaging, a technical review. Appl Sci. 2020;10:462. [Google Scholar]

- Demi M., Prediletto R., Soldati G., Demi L. Physical mechanisms providing clinical information from ultrasound lung images: Hypotheses and early confirmations. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2020;67:612–623. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2019.2949597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denina M., Scolfaro C., Silvestro E., Pruccoli G., Mignone F., Zoppo M., Ramenghi U., Garazzino S. Lung ultrasound in children with COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich C.F., Mathis G., Blaivas M., Volpicelli G., Seibel A., Wastl D., Atkinson N.S., Cui X.W., Fan M., Yi D. Lung B-line artefacts and their use. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1356–1365. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.04.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Zhang H., Xie J., Lin M., Ying L., Pang P., Ji W. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: Comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020;19 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.Y., Tao X.W., Zeng L.K., Wang W.Q., Li G. Application of pulmonary ultrasound in the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia in neonates. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:347–350. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20200228-00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala M.J. Ultrasound in COVID-19: A timeline of ultrasound findings in relation to CT. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Song C., Xu C., Jin G., Chen Y., Xu X., Ma H., Chen W., Lin Y., Zheng Y., Wang J., Hu Z., Yi Y., Shen H. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:706–711. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wang S., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Zheng C., Zheng Y., Zhang C., Min W., Zhou H., Yu M., Hu M.A preliminary study on the ultrasonic manifestations of peripulmonary lesions of non-critical novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). 2020b. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3544750. Accessed 28 Feb 2020. [DOI]

- Karacabey S., Sanrı E., Gencer E.G., Guneysel O. Tracheal ultrasonography and ultrasonographic lung sliding for confirming endotracheal tube placement: Speed and reliability. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:953–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein D., Goldstein I., Mourgeon E., Cluzel P., Grenier P., Rouby J.J. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonography in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:9–15. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguoro I., Pilotto C., Bonanni M., Ferrari M.E., Pusiol A., Nocerino A., Vidal E., Cogo P. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and newborns: A systematic review. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:1029–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limonta S., Monge E., Montuori M., Morosi M., Galli M., Franzetti F. Lung ultrasound in the management of pneumocystis pneumonia: A case series. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30:188–193. doi: 10.1177/0956462418797872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Liu F., Li J., Zhang T., Wang D., Lan W. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: Focus on pregnant women and children. J Infect. 2020;80:e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomoro P., Verde F., Zerboni F., Simonetti I., Borghi C., Fachinetti C., Natalizi A., Martegani A. COVID-19 pneumonia manifestations at the admission on chest ultrasound, radiographs, and CT: Single-center study and comprehensive radiologic literature review. Eur J Radiol Open. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2020.100231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L., Zhao H.T., Zhang Z.Y., Wang G.Y., Zhao H.L. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(3):e5713. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Zhang S., Chen B., Chen J., Xian J., Lin Y., Shan H., Zhen Su Z. A clinical study of noninvasive assessment of lung lesions in patients with Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) by bedside ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2020;41:300–307. doi: 10.1055/a-1154-8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Zhang L., Du H. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man M.A., Dantes E., Domokos Hancu B., Bondor C.I., Ruscovan A., Parau A., Motoc N.S., Marc M. Correlation between transthoracic lung ultrasound score and HRCT features in patients with interstitial lung diseases. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1199. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo P.H., Copetti R., Feller-Kopman D., Mathis G., Maury E., Mongodi S., Mojoli F., Volpicelli G., Zanobetti M. Thoracic ultrasonography: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1200–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercaldi C.J., Lanes S.F. Ultrasound guidance decreases complications and improves the cost of care among patients undergoing thoracentesis and paracentesis. Chest. 2013;143:532–538. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglioretti D.L., Johnson E., Williams A., Greenlee R.T., Weinmann S., Solberg L.I., Feigelson H.S., Roblin D., Flynn M.J., Vanneman N., Smith-Bindman R. The use of computed tomography pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongodi S., Orlando A., Arisi E., Tavazzi G., Santangelo E., Caneva L., Pozzi M., Pariani E., Bettini G., Maggio G., Perlini S., Preda L., Iotti G.A., Mojoli F. Lung ultrasound in patients with acute respiratory failure reduces conventional imaging and health care provider exposure to COVID-19. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46:2090–2093. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojoli F., Mongodi S., Orlando A., Arisi E., Pozzi M., Civardi L., Tavazzi G., Baldanti F., Bruno R., Iotti G.A., COVID-19 Pavia Crisis Unit Our recommendations for acute management of COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:207. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02930-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro F., Buonsenso D., Moruzzi M.C., Inchingolo R., Smargiassi A., Demi L., Larici A.R., Scambia G., Lanzone A., Testa A.C. How to perform lung ultrasound in pregnant women with suspected COVID‐19 infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55:593–598. doi: 10.1002/uog.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musolino A.M., Supino M.C., Buonsenso D., Ferro V., Valentini P., Magistrelli A., Lombardi M.H., Romani L., D'Argenio P., Campana A., Roman Lung Ultrasound Study Team for Pediatric COVID-19 (ROMULUS COVID Team) Lung ultrasound in children with COVID-19: Preliminary findings. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46:2094–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M.Y., Lee E.Y.P., Yang J., Yang F., Li X., Wang H., Lui M., Shing-Yen Lo C., Leung B., Khong P.L., Kim-Ming Hui C., Yuen K., Kuo M.D. Imaging profile of the COVID-19 infection: Radiologic findings and literature review. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020;2:e20003. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvenne A., Ticinesi A., Parise A., Prati B., Esposito M., Cocchi V., Crisafulli E., Volpi A., Rossi S., Bignami E.G., Baciarello M., Brianti E., Fabi M., Meschi T. Point-of-care chest ultrasonography as a diagnostic resource for COVID-19 outbreak in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:919–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C.J., Bhatt H.B., Parikh S.N., Jhaveri B.N., Puranik J.H. Bedside lung ultrasound in emergency protocol as a diagnostic tool in patients of acute respiratory distress presenting to emergency department. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2018;11:125–129. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_21_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri N., Lenge M., Buonsenso D., Coronavirus Infection in Pediatric Emergency Departments (CONFIDENCE) Research Group Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:187–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q., Wang X., Zhang L. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:849–850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda M.A., Chavez M.A., Hooper-Miele C.C., Gilman R.H., Steinhoff M.C., Ellington L.E., Gross M., Price C., Tielsch J.M., Checkley W. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:714–722. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone T., Quaglia F. Lung US features of severe interstitial pneumonia: Case report and review of the literature. J Ultrasound. 2017;11:247–249. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0241-x. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz E., Jhund P.S., Girerd N., Pivetta E., McMurray J.J.V., Peacock W.F., Masip J., Martin-Sanchez F.J., Ò M.i.r.ó., Price S., Cullen L., Maisel A.S., Vrints C., Cowie M.R., DiSomma S., Bueno H., Mebazaa A., Gualandro D.M., Tavares M., Metra M., Coats A.J.S., Ruschitzka F., Seferovic P.M., Mueller C., Study Group on Acute Heart Failure of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Expert consensus document: Reporting checklist for quantification of pulmonary congestion by lung ultrasound in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:844–851. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggiali E., Dacrema A., Bastoni D., Tinelli V., Demichele E., Mateo Ramos P., Marcianò T., Silva M., Vercelli A., Magnacavallo A. Can lung US help critical care clinicians in the early diagnosis of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia? Radiology. 2020;13 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggiali E., Vercelli A., Cillis M.G., Ioannilli E., Iannicelli T., Magnacavallo A. Triage decision-making at the time of COVID-19 infection: The Piacenza strategy. Intern Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02350-y. Accessed 9 May 2020. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontet J., Yic C., Díaz-Gómez J.L., Rodriguez P., Sviridenko I., Méndez D., Noveri S., Soca A., Cancela M. Impact of an ultrasound-driven diagnostic protocol at early intensive-care stay: A randomized-controlled trial. Ultrasound J. 2019;11:24. doi: 10.1186/s13089-019-0139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat G., Guinard S., Bizien N., Nowak E., Tonnelier J.M., Alavi Z., Renault A., Boles J.M., L'Her E. Can lung ultrasonography predict prone positioning response in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients? J Crit Care. 2016;32:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger N., Koratala A. Lung ultrasound: A valuable tool for the assessment of dialysis patients with COVID-19. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10157-020-01903-x. Accessed 19 May 2020. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig A., Copetti R. Lung ultrasound in community-acquired pneumonia and in interstitial lung diseases. Respiration. 2014;87:179–189. doi: 10.1159/000357449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Lima D.R., Yepes A.F., Birchenall Jimenez C.I., Mercado Diaz M.A., Pinilla Rojas D.I. Real-time ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in the intensive care unit: Prevalence of mechanical complications. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:25. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier E., Guri A., Balla U. Lung ultrasound cannot be used to screen for Covid-19 in children. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:4623–4624. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202005_21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., Cao Y., Alwalid O., Gu J., Fan Y., Zheng C. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokoohi H., Duggan N.M., García-de-Casasola Sánchez G., Torres-Arrese M., Tung-Chen Y. Lung ultrasound monitoring in patients with COVID-19 on home isolation. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.079. Accessed 28 May 2020. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati G., Demi M. The use of lung ultrasound images for the differential diagnosis of pulmonary and cardiac interstitial pathology. J Ultrasound. 2017;7(20):91–96. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0244-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati G., Demi M., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Demi L. The role of ultrasound lung artefacts in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13:163–172. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1565997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati G., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Buonsenso D., Perrone T., Briganti D.F., Perlini S., Torri E., Mariani A., Mossolani E.E., Tursi F., Mento F., Demi L. Is there a role for lung ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:1459–1462. doi: 10.1002/jum.15284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati G., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Buonsenso D., Perrone T., Briganti D.F., Perlini S., Torri E., Mariani A., Mossolani E.E., Tursi F., Mento F., Demi L. Proposal for international standardization of the use of lung ultrasound for patients with COVID-19: A simple, quantitative, reproducible method. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:1413–1419. doi: 10.1002/jum.15285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati G., Smargiassi A., Inchingolo R., Buonsenso D., Perrone T., Briganti D.F., Perlini S., Torri E., Mariani A., Mossolani E.E., Tursi F., Mento F., Demi L. On lung ultrasound patterns specificity in the management of COVID-19 patients. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jum.15326. Accessed 8 May 2020. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa A., Soldati G., Copetti R., Giannuzzi R., Portale G., Gentiloni-Silveri N. Early recognition of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia by chest ultrasound. Crit Care. 2012;16:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc11201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsung J.W., Kessler D.O., Shah V.P. Prospective application of clinician performed lung ultrasonography during the 2009 H1N1 influenza A pandemic: Distinguishing viral from bacterial pneumonia. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4:16. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrugno L., Bove T., Orso D., Barbariol F., Bassi F., Boero E., Ferrari G., Kong R. Our Italian experience using lung ultrasound for identification, grading and serial follow-up of severity of lung involvement for management of patients with COVID-19. Echocardiography. 2020;37:625–627. doi: 10.1111/echo.14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira A.L.S., Pazeli Júnior J.M., Bastos M.G. Role of point-of-care ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic: Our recommendations in the management of dialytic patients. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:30. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli G., Frascisco M. Sonographic detection of radio-occult interstitial lung involvement in measles pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.052. 128.e1–128.e3 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli G., Gargani L. Sonographic signs and patterns of COVID-19 pneumonia. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:22. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00171-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli G., Elbarbary M., Blavais M., Lichtenstein D.A., Mathis G., Kirkpatrick A.W., Melniker L., Gargani L., Noble V.E., Via G., Dean A., Tsung J.W., Soldati G., Copetti R., Bouhemad B., Reissig A., Agricola E., Rouby J.J., Arbelot C., Liteplo A., Sargsyan A., Silva F., Hoppmann R., Breitkreutz R., Seibel A., Neri L., Storti E., Petrovic T., International Liaison Committee on Lung Ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for International Consensus Conference on Lung Ultrasound (ICC-LUS) International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–591. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli G., Lamorte A., Villén T. What's new in lung ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1445–1448. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06048-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.T., Ding X., Zhang H.M., et al. Lung ultrasound can be used to predict the potential of prone positioning and assess prognosis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2016;20:385. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease and considerations during severe shortages. 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf. Accessed 27 February 2020.

- Xie X., Zhong Z., Zhao W., Zheng C., Wang F., Liu J. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: Relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 2020;12 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing C., Li Q., Du H., Kang W., Lian J., Yuan L. Lung ultrasound findings in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit Care. 2020;24:174. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02876-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Cao Q., Qin L., et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020;80:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Huang Y., Gao F., Yuan L., Wang Z. Lung ultrasonography versus chest CT in COVID-19 pneumonia: a two-centered retrospective comparison study from China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06096-1. Accessed 26 February 2020. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa K., Minami T. Point-of-care lung ultrasound findings in patients with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:1198–1202. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.H., Lee K.H., Kim J.Y., Lee Y.K., Ko H., Kim K.H., Park C.M., Kim Y.H. Chest radiographic and CT findings of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Analysis of nine patients treated in Korea. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:494–500. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef A., Serra C., Pilu G. Lung ultrasound in the COVID-19 pandemic: A practical guide for obstetricians and gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti M., Scorpiniti M., Gigli C., Nazerian P., Vanni S., Innocenti F., Stefanone V.T., Savinelli C., Coppa A., Bigiarini S., Caldi F., Tassinari I., Conti A., Grifoni S., Pini R. Point-of-care ultrasonography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED. Chest. 2017;151:1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.K., Li J., Yang J.P., Zhan Y., Chen J. Lung ultrasonography for the diagnosis of 11 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome due to bird flu H7 N9 infection. Virol J. 2015;26(12):176. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Zhong Z., Xie X., Yu Q., Liu J. Relation between chest CT Findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: A multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1072–1077. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]