Summary

pH and Ca2+ play important roles in regulating lysosomal activity and lysosome-mediated physiological and pathological processes. However, effective methods for simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+ is the bottleneck. Herein, a single DNA-based FLIM reporter was developed for real-time imaging and simultaneous quantification of pH and Ca2+ in lysosomes with high affinity, in which a specific probe for recognition of Ca2+ was assembled onto a DNA nanostructure together with pH-responsive and lysosome-targeted molecules. The developed DNA reporter showed excellent biocompatibility and long-term stability up to ∼56 h in lysosomes. Using this powerful tool, it was discovered that pH was closely related to Ca2+ concentration in lysosome, whereas autophagy can be regulated by lysosomal pH and Ca2+. Furthermore, Aβ-induced neuronal death resulted from autophagy abnormal through lysosomal pH and Ca2+ changes. In addition, lysosomal pH and Ca2+ were found to regulate the transformation of NSCs, resulting in Rapamycin-induced antiaging.

Subject Areas: Optical Imaging, Cellular Neuroscience, Technical Aspects of Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

A DNA-based FLIM reporter was developed for tracking lysosomal pH and Ca2+

-

•

It was found that autophagy could be induced by lysosomal pH and Ca2+

-

•

Aβ-induced neuronal death was due to pHly- and [Ca2+]ly-mediated autophagy abnormal

-

•

Antiaging-related transformation of qNSCs can be regulated by pHly and [Ca2+]ly

Optical Imaging; Cellular Neuroscience; Technical Aspects of Cell Biology

Introduction

Lysosomes are mainly acidic organelles that regulate cellular processes including catabolism by digestion and transmission of proteins, autophagy by the fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes as well as apoptosis by releasing cathepsin (Settembre et al., 2013; Luzio et al., 2007). Lysosomal dysfunction is of vital importance for the pathology of common neurodegenerative diseases and aging (Li et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017). The changes of pH and Ca2+ in lysosomes play important roles in lysosome-mediated physiological and pathological processes (Bagh et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2012). Under physiological conditions, pH value in lysosome is around 4.5 (Pan et al., 2016). This acidic environment of lysosome not only is crucial to maintain the proton gradient, which affects the permeability of lysosomal membranes toward different ions, like Ca2+, but also regulates the activity of lysosomes, which influences the formation of autolysosomes (Wan et al., 2014; Chung et al., 2019). Moreover, lysosome as significant “calcium pool” in live cells takes momentous roles in maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis as well as signal transduction (Zhu et al., 2016). For example, excessive reduction of Ca2+ concentration in lysosome leads to lysosomal dysfunction, resulting in malfunction of cellular uptake and excretion, and further causes autophagy dysfunction and aging. Therefore, it is very important to monitor the changes of pH and Ca2+ in the lysosome.

Over the past decades, several elegant methods have been developed for the detection of either pH or Ca2+ in lysosome (Pan et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2009; Egawa et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2016; Minamiki et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015). Previous work has also reported a pH-corrected measurement of Ca2+ concentrations in lysosomes, which was realized by calculation (Christensen et al., 2002; Narayanaswamy et al., 2019). Our group has been committed to develop analytical methods for determination of metal ions and oxidative stress-related biological species in live cells and brain (Zhu et al., 2012; Kong et al., 2011, 2012; Liu et al., 2017, 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b; Li et al., 2017a; Wang et al., 2019a). Recently, we have developed a ratiometric nanosensor to detect pH value and Ca2+ concentration in mitochondria (Liu et al., 2018a, 2018b). However, it is still hard to simultaneously perform imaging and biosensing of pH value and concentration of Ca2+ in lysosome because simultaneous detection of multiple substances may be affected by the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) or cross talk (Shcherbakova et al., 2018). Meanwhile, multiple substances detection requires the same localization, same fluorophore concentration ratios, which are hard to realize. In addition, imaging and biosensing of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ require high spatial and temporal resolution since lysosomes are only ∼0.5 μm, much smaller than other organelles (Omen et al., 2019). Stability is also a difficulty to be considered because of the strong digestion ability of lysosomes. Therefore, it is a challenging work to realize simultaneous quantification of multiple substances using a single probe in lysosomes.

To break through the above difficulties, a single FLIM-based DNA reporter was created for simultaneous imaging and real-time quantification of pH and Ca2+ in lysosome with high spatial and temporal resolutions (Figure 1A). Taking advantage of DNA nanostructure, including controllable size and shape as well as excellent biocompatibility (Song et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017a, 2017b; Zhang et al., 2001), the designed highly specific Ca2+ probe, pH-responsive probe, and lysosome-targeted molecules were co-assembled onto the vertexes of bipyramid-DNA (bDNA) to form a single nanoprobe with high stability and selectivity. On the other hand, fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) provides a powerful methodology for accurate biosensing and bioimaging with high spatial resolution at single cell level, which is usually independent of fluorophore concentrations, light sources, environmental changes, and spectral overlap between different fluorophores (Fan et al., 2018; Kawai et al., 2004). Therefore, the developed FLIM-based DNA reporter with long-term stability and good biocompatibility was successfully applied for simultaneous imaging and biosensing of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in single neural cell. Using the developed DNA reported, we found that th epH value increased with decreasing concentration of Ca2+ in lysosome, and vice versa. More importantly, it was discovered that autophagy can be regulated by lysosomal pH and Ca2+. Furthermore, Aβ-induced neuronal death was found to be ascribed to abnormal autophagy, which was regulated by lysosomal pH and Ca2+. Moreover, the relationship between aging and lysosomal pH and Ca2+ was further explored; it was found that aging-related qNSCs activation can also be controlled by improving lysosomal pH and reducing the concentration of Ca2+ in lysosomes.

Figure 1.

Synthesis and Characterization of DNA Reporter

(A) Schematic illustration for the working principle of the developed DNA reporter for simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+ in lysosome.

(B) TEM image of gCDs. Insets depict high-resolution TEM image and diameter distribution of gCDs.

(C) FTIR spectra of gCDs, CaL, and gCD@CaL.

(D) UV-vis absorption spectra and fluorescence emission spectra of gCDs and gCD@CaL under 405 nm excitation.

(E) Agarose electrophoresis analysis of DNA reporter. From left to right: DNA ladder (50–1,000 bp), DNA reporter, the mixture of gCD@CaL and bDNA-MP + RhB, bDNA-MP + RhB, gCD@CaL, DNA-CHO (aldehyde group), DNA-RhB, and DNA-MP, respectively.

(F) The threshold for fluorescent channels of RhB and gCD@CaL at excitation wavelength of 405 nm.

(G) Fluorescent lifetime decays of pH probe (RhB) and Ca2+ probe (gCD@CaL) collected from different channels.

Results

Assembly and Characterization of DNA Reporter

The lysosome-targeted DNA reporter for simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+ was designed as four parts: a specific element for recognition of Ca2+–fluorescent carbon dots conjugated with calcium ligand (gCD@CaL), pH-responsive Rhodamine B (RhB), lysosome-targeted 2-(4-morpholinyl) ethyl isothiocyanate (MP), and a bipyramidal DNA (bDNA) nanostructure with principal axis length of ∼14 nm. The recognition elements for Ca2+ and pH together with MP were assembled and conjugated onto the bDNA through chemical bonds, as shown in Figure 1A. As a starting point of this work, gCDs were prepared from m-phenylenediamine by hydrothermal synthesis according to the previous report (Jiang et al., 2015). From transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image shown in Figure 1B, the diameter of gCDs was estimated to 3.00 ± 0.25 nm (n = 100). The high-resolution TEM image demonstrated the typical lattice spacing of gCDs was 0.21 nm, consistent with the in-plane lattice spacing of graphene (100) (Jiang et al., 2015). Meanwhile, atomic force microscope (AFM) image proved that gCDs were monodispersed with average height of 1.25 ± 0.06 nm (n = 100, Figure S1A). On the other hand, the ligand for specific recognition of Ca2+, CaL, was designed and synthesized (Scheme S1; Data S1). The dissociation constant (Kd) of CaL for Ca2+ was calculated to be 346 ± 17 μM (n = 5), indicating CaL has a strong coordination effect on Ca2+. Then, CaL was conjugated onto the surface of gCDs to form gCD@CaL through Schiff base reaction between -NH2 group of gCDs (1,048 cm−1) and -CHO group of CaL (∼1,725 cm−1 and ∼3,039 cm−1). As shown in Figure 1C, after gCD@CaL was formed, a new peak located at ∼1,640 cm−1 was observed, which belongs to the stretching vibration of C=N. It should be pointed out that, after gCD@CaL was incubated with buffer solutions of different pH (pH = 3.00, 4.01, 5.00) for 56 h, negligible changes (<1.0%) at ∼1,640 cm−1 (υC=N) were observed for gCD@CaL (Figure S1B). These results prove that CaL was successfully conjugated onto gCDs with high stability. Moreover, UV-vis absorption spectrum of gCDs shows well-defined absorption peaks at 214, 296, and 356 nm, which were attributed to π-π∗ and n-π∗ transition, respectively. After CaL was conjugated onto gCDs, the absorption bands of gCDs@CaL red-shifted, from 214 to 254 nm, 295 to 313 nm, and 351to 364 nm (Figure 1D). Meanwhile, the fluorescent intensity of gCDs was decreased and the fluorescent lifetime was shortened (Figures 1D and S2G), clearly demonstrating that the electrons of gCDs transferred to CaL ligands after the successful production of gCD@CaL probe.

Then, a bDNA nanostructure was designed and prepared with different functional groups (-NH2 or -CHO) for further assembling gCD@CaL, RhB, and MP (Erben et al., 2007). From bio-fast AFM images (Figure S1D), a uniform distribution of bDNA with a typical bipyramidal morphology can be observed. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) results also suggest the high generation yield of bDNA. Meanwhile, RhB or MP-labeled DNA strands (DNA-RhB, DNA1-MP, DNA2-MP and DNA3-MP) were synthesized (Figures S1C, S1E, and S1F) to produce bDNA-MP + RhB probe. Finally, gCD@CaL, MP, and RhB were successfully assembled onto bipyramidal DNA nanostructure to generate DNA reporter, bDNA-MP + RhB + gCD@CaL, for simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+, which was confirmed by agarose electrophoresis as shown in Figure 1E. In addition, dynamic light scattering (DLS) results show that the average diameter of individual gCD@CaL and bDNA-MP + RhB probes were 17.82 ± 5.00 and 63.64 ± 6.02 nm (n = 5), respectively. After gCD@CaL was assembled onto bDNA-MP + RhB, the average diameter of the produced bDNA-MP + RhB + gCD@CaL probe was increased to 79.22 ± 7.04 nm (n = 5, Figure S1G). Furthermore, in order to confirm the conjugated number of gCD@CaL on each bipyramidal DNA unit, TEM was used to characterize the assembled DNA reporter. The assembly of gCD@CaL with bDNA-MP + RhB produced monodispersed and disordered gCD@CaL (Figure S1H), but it is difficult to observe the conjugated number of gCD@CaL on each bipyramidal DNA unit. Subsequently, a new bDNA-1 with two bare -CHO groups on vertices was prepared and further used to assemble with gCD@CaL. As shown in Figure S1I, two gCD@CaL particles were assembled onto bDNA-1. The distance between these two gCD@CaL particles was estimated about 14 nm from TEM image, which was consistent with the distance of the vertex of bDNA-1. All these results proved the successful assembly of bDNA-MP + RhB + gCD@CaL probe.

Simultaneous Determination of pH and Ca2+ Using the Developed DNA-Based FLIM Reporter

The analytical performance of the DNA reporter for simultaneous sensing of pH and Ca2+ was evaluated. As shown in Figure 1F, gCD@CaL and RhB assembled onto DNA nanostructure showed emission peaks located at 514 and 583 nm under excitation of 405 nm, respectively. Meanwhile, the average fluorescence lifetimes of gCD@CaL and RhB were estimated to be 0.96 ns (1.86 ns, 41%; 0.33 ns, 59%) and 2.85 ns (3.44 ns, 78.5%; 0.70 ns, 21.5%), as demonstrated in Figure 1G, from Equations (1) and (2) when the signals were collected from 450–550 and 610–700 nm, respectively. Thus, the average lifetime of RhB and gCD@CaL in the DNA reporter can be distinguished clearly.

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

where is the lifetime, is the fractional amplitude with , is the fractional intensity of each decay time to the steady-state intensity, and is the average fluorescence lifetime of the probe.

With increasing concentration of Ca2+, the fluorescence lifetime of gCD@CaL channel (450–550 nm) was prolonged from 2.92 to 7.83 ns as demonstrated in Figure 2A, accompanied with fluorescent enhancement (Figures S2A and S2B). As summarized in Figure 2B, the average fluorescence lifetime of gCD@CaL channel displayed a good linearity with Ca2+ concentration in the range of 10–600 μM. The detection limit was calculated to be 2.53 ± 0.04 μM (S/N = 3, n = 5). This Ca2+-induced fluorescence enhancement and lifetime prolongation of gCD@CaL can be attributed to the inhibition of electron transfer process between CaL and gCDs. In the absence of Ca2+, gCD@CaL showed clear absorption peaks at 254, 288, 313, and 364 nm. The absorption bands of gCD@CaL had red-shifts compared with those of gCDs, which were attributed to the electrons of gCDs transferred to CaL ligands. However, with the increasing concentrations of Ca2+, the absorption peak at 364 nm of gCD@CaL was decreased, whereas the absorption peak at 288 nm blue-shifted to 282 nm (Figures S2E and S2F), together with the fluorescence recovery of gCD@CaL. (Figure 2A). These results demonstrated that, after gCD@CaL was conjugated with Ca2+, the electron transfer from gCDs to CaL was inhibited. Moreover, the electron transfer between gCDs and CaL was proved by transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS) (Sakamoto et al., 2005; Tachikawa et al., 2007). As for gCDs, a negative absorption band with peak at 500 nm and a broad positive absorption band with peak at 640 nm were observed, which were attributed to stimulated emission (SE) and excited state absorption (ESA), respectively (Figure S2H). However, after gCDs were conjugated with CaL to form gCD@CaL, the peak at 500 nm had an apparent decrease, indicating that electrons of gCDs were transferred to CaL, resulting in the decrease of stimulated emission (Figure S2I). More interestingly, with the addition of Ca2+, the peak at 500 nm was correspondingly recovered, which should be contributed to the inhibition of electrons transformation from gCDs to CaL (Figure S2J). Furthermore, the TA (transient absorption) kinetic traces were recorded at 640 nm. As shown in Figure S2K, two distinct signals for the lifetimes of gCDs were 3.31 and 36.82 ps, indicating two excitation pathways were observed for fluorescence emissions of gCDs. Meanwhile, the lifetime of gCDs@CaL became 7.18 and 185.36 ps after CaL was conjugated onto gCDs, indicating that conjugation of CaL onto gCDs caused a new decay pathway in the excited-state relaxation. This new decay pathway resulted from the electron transfer between CaL and gCDs. However, with the addition of 100 μM Ca2+, the lifetimes of gCDs@CaL signals changed back, implying electron transfer-related new decay pathway in the excited-state relaxation was inhibited.

Figure 2.

Analytical Performance of the DNA Reporter for Simultaneous Determination of Ca2+ and pH

(A) Fluorescence lifetime decay curves of gCD@CaL in the presence of various concentrations of Ca2+ (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700 μM).

(B) Calibration curve between average fluorescence lifetime of gCD@CaL and various concentrations of Ca2+ in (A).

(C) Fluorescence lifetime decay curves of RhB in the presence of different pH values (1.95, 2.09, 3.29, 4.10, 5.02, 6.09, 6.58, 7.00, 7.50).

(D) Calibration curve between average fluorescence lifetime of RhB and different pH in (C).

(E) Fluorescence reversibility responses of RhB between pH 2.80 and 7.00.

(F) Average fluorescence lifetime of the reporter obtained at excitation wavelength of 405 nm at different pH values (1.95, 2.09, 3.29, 4.10, 5.02, 6.09, 6.58, 7.00, 7.50) in the presence of different concentrations of Ca2+ (0, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700 μM).

(G) Calibration curve between average fluorescence lifetime of gCD@CaL and RhB at different pH values in the presence of different concentrations of Ca2+ in (F).

(H) 3D surface plot of gCD@CaL channel lifetime response as a function of Ca2+ concentration and pH.

(I) 3D surface plot of RhB channel lifetime as a function of Ca2+ concentration and pH. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group.

Similarly, the average fluorescence lifetime of RhB channel (610–700 nm) was prolonged from 0.92 ns to 1.33 ns with decreasing pH from 7.50 to 1.95 (Figure 2C). The increase in the fluorescence intensity of RhB was also observed (Figures S2C and S2D). The average fluorescence lifetime of RhB showed a good linear relationship with pH value from 2.24 to 6.58, and pKa was calculated to be 3.58 ± 0.82 (n = 5, Figure 2D), which is very beneficial for pH sensing in lysosome. It is mentioned that RhB molecule shows an emission peak around 515 nm, which is attributed to the emission of xanthine part of RhB. Under alkaline conditions, the molecule maintains a spiral loop state condition. However, the delocalization of electrons in xanthene was enhanced after addition of H+, and the structure of RhB changed from spirocyclic (non-fluorescent) to ring-open (fluorescent) forms (Shen et al., 2015). In addition, RhB shows a good reversibility when pH changed between 7.00 and 2.80 (Figure 2E).

More importantly, the DNA reporter was used for simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+. The average fluorescence lifetime of the developed DNA reporter gradually prolonged with increasing concentration of Ca2+ from 0.2 to 700 μM as well as decreasing pH value from 7.50 to 1.95. Because the fluorescence emission spectra for gCD@CaL and RhB channels were well separated (Figure 1F), the lifetimes with the fluorescent spectra of gCDs@CaL and RhB channels were collected from 450 to 550 nm and 610 to 700 nm. The average fluorescence lifetime of gCD@CaL channel displayed a good linearity with Ca2+ concentration in the range of 10–650 μM as demonstrated in Figure 2G, and the detection limit was estimated to be 2.36 ± 0.07 μM (S/N = 3, n = 5), as summarized in Equation (3):

| (Equation 3) |

Similarly, the average fluorescence lifetime of RhB channel displayed a good linearity with pH from 2.25 to 6.70 (Figure 2G), and pKa was calculated to be 3.37 ± 0.62 (n = 5), as summarized in Equation (4):

| (Equation 4) |

Moreover, this nanoprobe also showed rapid response dynamics toward pH and Ca2+. The response times for 1.0 pH and 200 μM Ca2+ were estimated to be 2 and 4 s, respectively (Figure S2L). Furthermore, there are no cross talk or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between RhB and gCD@CaL assembled onto DNA nanostructure (Figures 2H and 2I).

Since the environment in live cells is complicated, the selectivity of the developed DNA reporter was also tested against potential biological species including metal ions, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and amino acids. No obvious responses (<2.9%) were observed on the channels of RhB and gCD@CaL (Figures S3A–S3F) for metal ions such as K+ (50 mM), Na+ (100 mM), Mg2+ (300 μM), Al3+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Fe3+, and Cu2+ (10 μM); amino acids; and ROS including H2O2, O2⋅-, 1O2, and ⋅OH. Moreover, in the competition tests, negligible effects of other metal ions, amino acids, and ROS were obtained for the responses of RhB and gCD@CaL channels (<3.2%) in the developed probe. All these results demonstrated that the developed FLIM reporter showed high selectivity and accuracy, as well as quick response, which was very powerful for real-time sensing and simultaneous quantifying of pH and Ca2+ in live cells.

The Stability, Biocompatibility, and Accuracy of the Developed DNA Reporter

For further application, the stability of the developed DNA reporter was also estimated. Lysosomes as acid organelles, which contain many hydrolytic enzymes, can easily degrade substances and probes (Wang et al., 2019b). The stability of the DNA reporter in lysosome was also estimated, and the ability of the developed nanoprobe for targeting lysosome was first investigated. Co-localization imaging results showed that the fluorescence of developed nanoprobe merged well with that of commercialized lysosomal dye (LysoTracker green) both in neurons and stem cells. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated as 0.92 and 0.94 in neurons and stem cells, respectively (Figure 3A), suggesting that the present probe was mainly located in lysosome. In addition, no obvious change (<2.0%) was obtained for the fluorescent intensity of gCD@CaL even after the DNA reporter entered into lysosomes for 56 h (Figures S3M and S3N). Moreover, the fluorescence lifetime signals of the developed nanoprobe remained stable (<8.5%) in lysosomes and the DNA reporter showed high structural stability even after the nanoprobe was incubated with cells for 56 h, which fulfills the requirement for cell experiments. However, the overall signals of the developed nanoprobe in lysosomes decreased to 54%, and the pH channel and gCD@CaL channel signals decreased to 52% and 58%, respectively, after they were incubated with cells for 72 h (Figures 3B and 3C). Meanwhile, the DNA structure was observed to keep stable within 56 h (94%) and then gradually degraded for about 48% at 72 h (Figure 3D). Furthermore, after the assembled DNA reporter was exposed to a Xe lamp (90 W) for 2.5 h, no obvious photobleaching was observed from both signals of gCD@CaL and RhB channels (<3.8%), which fulfills the requirement for cell experiments (Figure 3E). All these results demonstrated that the assembled DNA reporter showed high structural stability and long-term photostability.

Figure 3.

Intracellular Stability of the Developed Nanoprobe

(A) Confocal fluorescence images of neurons and stem cells treated with the developed nanoprobe and LysoTracker Green. Scale bar: 15 μm.

(B) Confocal fluorescence images of neurons treated with the present nanoprobe and LysoTracker Green for different times (5, 24, 48, 56, 64, 72 h). Scale bar: 10 μm.

(C) The colocation correlation of neurons treated with the present nanoprobe and LysoTracker Green.

(D) Agarose electrophoresis (2%) analysis of DNA reporter incubated with neurons for different times (5, 24, 48, 56, 64, 72 h).

(E) Normalized fluorescence intensity of RhB and gCD@CaL obtained from DNA Reporter upon exposure to Xe lamp (90 W). Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group.

Before imaging and biosensing of lysosomal pH and Ca2+, the cytotoxicity and biocompatibility of the developed DNA reporter were first evaluated. MTT results showed that the cell viability was higher than 92% even after the nanoprobe (25 μM) was incubated with cells for 48 h; this concentration of nanoprobe was higher than that used in live cells (Figures S3G and S3H). In addition, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) results confirmed that no obvious differences were observed for live cells, viable apoptotic cells, late apoptotic cells, and non-viable cells after the cells were incubated with different concentrations of the developed nanoprobe (Figures S3I and S3J), proving good biocompatibility of the developed fluorescent probe. The low cytotoxicity and good biocompatibility of this nanoprobe was attributed to the presence of non-toxicity DNA framework and biocompatible gCDs.

Meanwhile, the commercial lysosomal pH probe (DND-189) was employed to calibrate the accuracy of our developed method. As shown in Figures S3K and S3L, the fluorescence intensity of DNA-189 displayed a good linearity with pH from 2.93 to 6.09, and pKa was calculated to about 5.2, as summarized in Equation (5):

| (Equation 5) |

In addition, the average fluorescence lifetime of RhB also showed a good linearity with pH from 2.24 to 6.58, which obeys Equation (4).

Then, T test method was used to compare the determined results from the commercial probe and those from our developed nanoprobe. As summarized in Table S2, no significant difference was obtained between two probes. These results proved that the developed nanoprobe showed the same accuracy with the commercial probe.

Real-Time Tracking and Simultaneous Quantification of Lysosomal pH and Ca2+ Regulating the Level of Autophagy in Single Neuron

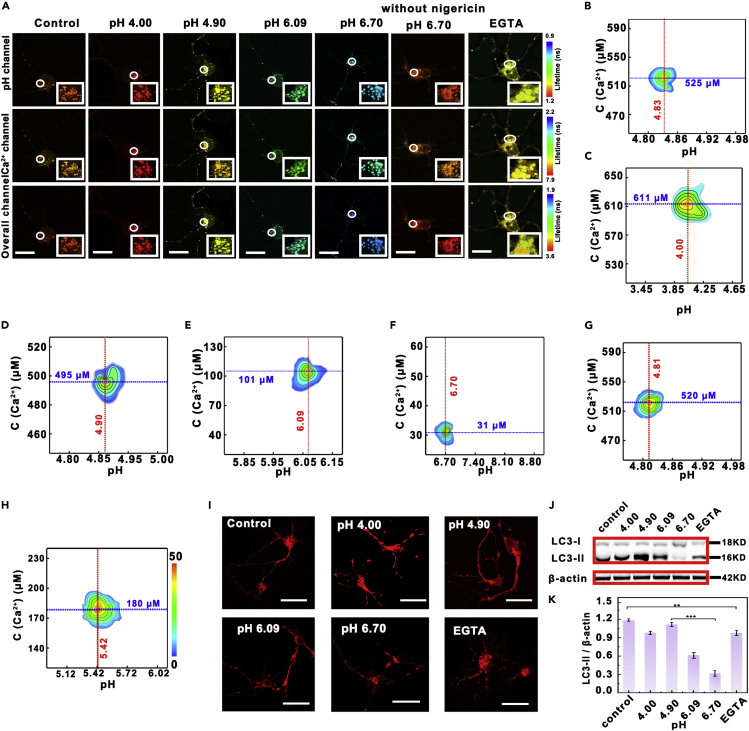

Taking the advantages of the developed nanoprobe, including high selectivity and accuracy, as well as long-term stability, the developed FLIM nanoprobe was applied for monitoring the levels of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ (pHly and [Ca2+]ly) in neurons. As shown in Figure 4A, under physiological conditions, lysosomal pH value and Ca2+ concentration were estimated to be 4.83 ± 0.03 and 525 ± 17 μM (n = 100), respectively. With increasing extracellular pH value from 4.00 to 6.70, the fluorescence lifetime of overall channel was shortened. The lysosomal pH was increased from 4.00 ± 0.24 to 6.70 ± 0.13 (n = 100). Interestingly, the concentration of lysosomal Ca2+ was also decreased from 611 ± 18 to 31 ± 2 μM (n = 100) (Figures 4B–4G). It should be pointed out that no obvious change was observed for pHly or [Ca2+]ly at pH 6.70 in the absence of nigericin. These results proved that the increase of pHly caused the decrease of [Ca2+]ly concentration. On the other hand, after neurons were treated with EGTA, a chelator for Ca2+, the concentration of lysosomal Ca2+ was, as expected, decreased to 180 ± 11 μM (n = 100). However, lysosomal pH was found to be increased to 5.42 ± 0.27 (n = 100) (Figure 4H). These results demonstrated that lysosomal pH was closely related to the concentration of Ca2+, that is, the concentration of lysosomal Ca2+ was decreased with increasing lysosomal pH. The lysosomal pH also correspondingly went up when the concentration of Ca2+ in lysosomes was decreased.

Figure 4.

Co-localization Imaging and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in Neurons

(A) Confocal fluorescence lifetime images of neurons collected from pH channel, Ca2+ channel, and overall channel treated with the present nanoprobe at different pH values (4.00, 4.90, 6.09 6.70, 6.70 without nigericin) and in the presence of EGTA, respectively. Scale bar: 15 μm.

(B–H) Lysosomal density scatter profiles of neurons at (B) control, (C) pH 4.00, (D) pH 4.90, (E) pH 6.09, (F) pH 6.70, (G) 6.70 without nigericin, and (H) in the presence of EGTA. The density plot was pseudo color, where red and blue correspond to populations with higher and lower frequencies of occurrence. The data were obtained from 100 lysosomes in ten cells.

(I) Fluorescence images of neurons incubated with MDC after lysosomal pH changed from 4.00 to 6.70 in neurons. Scale bar: 30 μm.

(J) Immunoblotting analysis of relative levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in lysate purified from the neurons with different lysosomal pH values.

(K) The quantification of LC3-II/β-actin expression from western blot results. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group. Assume that the significance level of the statistical test is 0.01 (∗∗), and 0.001 (∗∗∗) (n = 20; ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001).

Next, the developed probe was employed to investigate the effects of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ on autophagy and further to understand the molecular pathway of autophagy, because autophagy plays important roles in living body. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) was selected as the fluorescent probe for tracking autophagy level, which can selectively accumulate in autophagic vesicles during autophagy (Biederbick et al., 1995). As shown in Figure 4I, the fluorescence of neurons incubated with MDC gradually increased from pH 4.00 to 4.90 and then decreased from 4.90 to 6.70, indicating that the level of autophagy is closely related to lysosomal pH. The optimized pH value for autophagy was found to be 4.90, which agrees well with that of normal pH in lysosome. Overly acidic (lower than normal pH in lysosome) and basic (higher than normal pH) are all negative to the level of autophagy. More interestingly, the event of autophagy was also weakened when the neurons treated with 10 μM EGTA, a chelator for Ca2+, until [Ca2+]ly decreased from 525 ± 35 to 180 ± 11 μM, suggesting that the level of autophagy was correspondingly decreased with decreasing concentration of Ca2+. Meanwhile, autophagy level was confirmed by the amount of light chain 3 (LC3), a membrane microtubule-associated protein 1. LC3 is the credible biomarker of autophagy, which can lose peptide fragments to produce LC3-I, and the produced LC3-I can bind with phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) to form LC3-II during autophagy (Cui et al., 2018; Laraia et al., 2019; Li et al., 2018). As shown in Figures 4J and 4K, the level of LC3-II/β-actin gradually went up from 0.92 ± 0.05 to 1.17 ± 0.06 according to the quantification of western blot as lysosomal pH increased from 4.00 to 4.90. However, the level of LC3-II/β-actin began to decrease and down to 0.32 ± 0.01, after lysosomal pH was continuously increased to 6.70.

On the other hand, after adding chelator for Ca2+ (EGTA), the fluorescence of neurons incubated with MDC was decreased compared with those under physiological condition. Meanwhile, the intensity ratio of LC3-II to β-actin was 0.97 ± 0.07 (Figures 4J and 4K), indicating the level of autophagy decreased with decreasing concentration of lysosomal Ca2+. Taken together, these results demonstrated that lysosomal pH and Ca2+ greatly contributed to the level of autophagy.

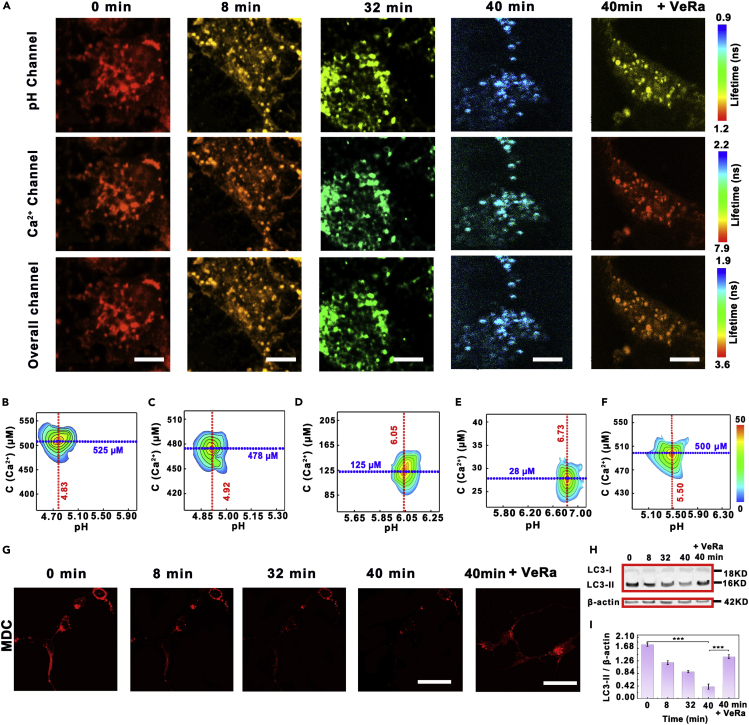

Moreover, it has been reported that bafilomycin A1 can inhibit the lysosomal proton pump and elevate pH in lysosome, which in turn leads to the decrease of Ca2+ concentration in lysosome (Chung et al., 2019). Therefore, the effect of bafilomycin A1 on lysosomal pH and Ca2+ as well as autophagy was further investigated in detail by our accurate probe. It was found that, after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min (Figures 5A and S4A), lysosomal pH increased from 4.83 ± 0.05 to 6.73 ± 0.16, whereas lysosomal Ca2+ decreased by from 525 ± 35 to 28 ± 3 μM. Meanwhile, the detailed kinetics during the process was also observed. As shown in Figure S4B, lysosomal pH started to increase from 4.83 ± 0.05 after the cells were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 1 min and then quickly increased to 5.37 ± 0.12 in the following 15 min. However, lysosomal Ca2+ concentration started to decrease from 525 ± 13 μM after the cells were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 3 min, then decreased to 225 ± 8 μM. In addition, after removing the stimulation of bafilomycin A1 at 16 min, seldom increasing of lysosomal pH was observed in the following 9 min. It should be pointed out that the lysosomal Ca2+ slowly decreased before it tended to stabilize at 218 ± 11 μM in the absence of bafilomycin A1 stimulation. On the other hand, when the cell culture solution was changed to neurobasal medium and Britton-Robinson (BR) buffer (40 mM) containing 120 mM KCl, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, and 5 mM glucose at pH 4.8, lysosomal pH immediately decreased from 5.37 ± 0.19 to 4.85 ± 0.08 within 10 min. Interestingly, the lysosomal Ca2+ did not start to change until the pH of the lysosome decreased to 5.25 ± 0.11. All these results proved that the changes of lysosomal Ca2+ was induced by pH changing in lysosome. More interestingly, addition of Ca2+ channel inhibitor verapamil (VeRa), which can target the subunit of L-type voltage-gated calcium channel, further inhibits the channel activation and blocks the influx of Ca2+ by depolarizing the cell membrane and increasing the threshold potential of calcium channels (Kwon and Triggle, 1991; Rampe and Triggle, 1990; Green et al., 2007), significantly weakening the changes of lysosomal pH and Ca2+. pHly only increases by 0.67 ± 0.07, whereas [Ca2+]ly only decreased by 25 ± 5 μM after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min in the presence of VeRa (Figures 5B–5F).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging and Quantification of Lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in Response to Bafilomycin A1 in Neurons

(A) Enlarged confocal fluorescence lifetime images of neurons collected from pH channel, Ca2+ channel, and overall channel after the neurons were stimulated by 10 μM bafilomycin A1 for different times (0, 8, 32, 40 min), respectively. For comparison, the image of neurons stimulated by bafilomycin for 60 min in the presence of verapamil was also obtained. Scale bar: 8 μm.

(B–F) Lysosomal density scatter profiles after neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for (B) 0, (C) 8, (D) 32, (E) 40, and (F) 40 min in the presence of VeRa. The density plot was pseudo color, here red and blue correspond to populations with higher and lower frequencies of occurrence. The data were obtained from 100 lysosomes in 10 cells.

(G) Fluorescence images of neurons incubated with MDC after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for different times. Scale bar: 25 μm.

(H) Immunoblotting analysis of relative levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in lysate purified from the neurons that were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for different times.

(I) The quantification of LC3-II/β-actin expression from western blot results. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group. Assume that the significance level of the statistical test is 0.001 (∗∗∗) (n = 20; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001).

Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 5G, with the extension of stimulation time by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min, the fluorescence of neurons incubated with MDC, a tracking marker for autophagy, gradually decreased. More interestingly, in the presence of VeRa, no obvious change was observed after the neurons incubated with MDC. These results demonstrated that, with the extension of the stimulation time of bafilomycin A1, the level of autophagy was correspondingly decreased. Furthermore, these results were verified using the western blot. As shown in Figure 4H, with the stimulation of bafilomycin A1, the level of LC3-II was decreased obviously. The intensity ratio of LC3-II to β-actin decreased from 1.71 ± 0.06 to 0.52 ± 0.05 after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min, confirming that the level of autophagy was decreased after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min. Notably, little decrease (0.04 ± 0.01) of LC3-II was observed after the neurons were stimulated by bafilomycin A1 for 40 min in the presence of VeRa, demonstrating that VaRa can prevent bafilomycin A1-induced decreasing of autophagy (Figures 4H and 4I). These results proved that our developed DNA reporter can be used for sensing and quantifying of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in live cells, further indicating that lysosomal pH and Ca2+ showed close relationship with the level of autophagy.

Aβ Regulated Autophagy Level by Changing Lysosomal pH and Ca2+

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a typical neurodegenerative disease, which can be characterized by losing of hippocampal neurons and accumulation of amyloid (Aβ) in the brain. It has been reported that Aβ aggregates disturb lysosomal function and further result in abnormal autophagy (Tian et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017; Komatsu et al., 2006; Khurana et al., 2010). Thus, we first investigated the neurotoxicity of aggregated Aβ1-42, the main component of Aβ plaque. The cell viabilities decreased with the extension of stimulation time as well as the increase of aggregated Aβ1-42 concentration (Figure S4C). The cell viability was found to be decreased to 42 ± 7% after the neurons were stimulated by 60 μM aggregated Aβ1-42 for 48 h. When the concentration of aggregated Aβ1-42 was increased to 100 μM, the cell viability was decreased down to 21 ± 4% after the neurons were stimulated for 48 h. This result indicated that the aggregated Aβ1-42 had close relationship with the neuronal death. Autophagy has been considered to contribute to cell death (Yang et al., 2017; Kroemer and Jäättelä, 2005; Yang and Klionsky, 2010); therefore, the level of autophagy after the neurons were stimulated by aggregated Aβ1-42 was also investigated. As shown in Figure 6A, the fluorescence of the neurons incubated with MDC gradually decreased after the neurons were stimulated by 60 μM aggregated Aβ1-42 from 0 to 48 h. Meanwhile, the amount of LC3-II gradually decreased after the neurons were stimulated by Aβ1-42 from 0 to 48 h (Figure 6B). The intensity ratio of LC3-II to β-actin changed from 1.10 ± 0.08 to 0.74 ± 0.05 after the neurons were stimulated by Aβ1-42 for 48 h, indicating the level of autophagy was gradually decreased after the neurons were stimulated by 60 μM aggregated Aβ1-42 from 0 to 48 h. Notably, seldom decrease (0.03 ± 0.01) of LC3-II was observed after neurons were stimulated by Aβ1-42 for 48 h in the presence of VeRa, demonstrating that VaRa can prevent Aβ-induced decreasing of autophagy (Figure 6C). Previous studies have reported that autolysosomes were produced by fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes, which contributed to autophagy level. For understanding the molecular mechanism of Aβ1-42-induced autophagy, we explored the changes of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in neurons during Aβ1-42 stimulation. With the extension of stimulation time from 0 to 48 h during 60 μM Aβ1-42 stimulation, pHly was continuously increased from 4.83 ± 0.05 to 6.90 ± 0.30, whereas [Ca2+]ly was decreased from 525 ± 20 to 15 ± 1 μM. More importantly, addition of Vera can apparently inhibit the increase in pHly (5.43 ± 0.27) and the decrease in [Ca2+]ly (447 ± 23 μM) (Figures 6D–6J and S4D). Since normal pH value and Ca2+ concentration are essential for lysosomal functions, these significant changes in lysosomal pH and Ca2+ concentration would lead to lysosomal dysfunction, further reduce autophagy level by inhibiting the fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes. Consequently, Aβ-induced neuronal death was attributed to Aβ-caused lysosomal dysfunction by greatly improving lysosomal pH and significantly reducing lysosomal Ca2+ concentration, which give rise to the autophagy abnormal, thus resulting in neuronal death (Figure 6K).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging and Quantification of Lysosomal Ca2+ and pH in Neurons under Stimulation of Aggregated Aβ1−42

(A) Fluorescence images of neurons incubated with MDC after the neurons were stimulated by aggregated Aβ1−42 for different times (0, 6, 12, 24, 48 h and 48 h in the presence of VeRa). Scale bar: 25 μm.

(B) Immunoblotting analysis of relative levels of LC3-I and LC3-II in lysate purified from the neurons that were incubated with 60 μM Aβ for different times (0, 6,12, 24, and 48 h) and 60 μM Aβ for 48 h in the presence of VeRa.

(C) The quantification of LC3-II/β-actin expression from western blot results. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group. Assume that the significance level of the statistical test is 0.001 (∗∗∗) (n = 20; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001).

(D) Enlarged confocal fluorescence lifetime images of neurons collected from pH channel, Ca2+ channel, and overall channels after neurons were stimulated with 60 μM aggregated Aβ1−42 for different times (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h) and 60 μM aggregated Aβ1−42 for 48 h in the presence of VeRa. Scale bar: 8 μm.

(E–J) Lysosomal density scatter profiles of neurons after incubation with Aβ for (E) 0, (F) 6, (G) 12, (H) 24, (I) 48 hr and (J) 48 hr in the presence of VeRa. The density plot was pseudo color, red and blue correspond to populations with higher and lower frequencies of occurrence. The data were obtained from 100 lysosomes in 10 cells.

(K) Schematic of lysosomal pH and Ca2+-mediated regulation of autophagy.

Activation of Quiescent Neural Stem Cell for Antiaging by Regulating Autophagy

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are a typical type of cells in the nervous system, which can produce newborn neurons during the process of neurogenesis. Generally, NSCs can be divided into quiescent NSCs (qNSCs) and active NSCs (aNSCs) (Figures S5A–S5F). More interestingly, qNSCs can be activated and transformed into aNSCs, and this process was regulated by lysosomal activity and the level of autophagy (Leeman et al., 2018). Meanwhile, we have found that lysosomal activity and autophagy levels can be regulated by lysosome pH and Ca2+ concentration. Thus, in order to understand the molecular mechanism regulating the activation ability of qNSCs, pH value and Ca2+ concentration of qNSCs and aNSCs in lysosomes and the degree of autophagy were first measured. As shown in Figures 7A and 7B, lysosomal pH in qNSCs was estimated to 4.98 ± 0.16, slightly higher than that in aNSCs (4.70 ± 0.12). However, lysosomal Ca2+ concentration in qNSCs (465 ± 25 μM) was obviously lower than that in aNSCs (575 ± 20 μM). At the same time, we observed that LC3-II/β-actin was about 0.47 ± 0.07 in qNSCs by western blot and the degree of autophagy was lower than that of aNSCs (LC3-II/β-actin = 1.10 ± 0.04) (Figures 7J and 7K). Therefore, the level of autophagy in aNSCs is higher than that in qNSCs. Since qNSCs can be activated and transformed into aNSCs under simultaneous stimulation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), the changes in the levels of autophagy as well as in lysosomal pH value and Ca2+ concentration in qNSCs under the stimulation of EGF and bFGF were further investigated. As shown in Figures 7C and 7D, lysosomal pH value and Ca2+ concentration in qNSCs were estimated to be 4.98 ± 0.16 and 465 ± 25 μM, respectively. However, after qNSCs were stimulated by EGF and bFGF for 2 days, lysosomal pH value and Ca2+ concentration in qNCSs changed to 4.86 ± 0.38 and 523 ± 47 μM, which were similar to those obtained in aNSCs. Furthermore, from the western bolt results, we found that the level of autophagy (LC3-II/β-actin = 1.03 ± 0.02) in qNCSs rose and approached the level of autophagy in aNSCs (LC3-II/β-actin = 1.18 ± 0.05) upon stimulation, indicating the level of autophagy was also increased. In addition, FACS results implied that 46.8 ± 2.5% of qNSCs were transformed into aNSCs after qNSCs were stimulated by EGF and bFGF for 2 days (n = 5) (Figures 7E and 7F). More interestingly, after qNCSs were stimulated by EGF and bFGF in the presence of VeRa for 2 days, seldom change was observed for lysosomal pH (4.92 ± 0.18) and Ca2+ concentration (480 ± 32 μM) in qNCSs, which were similar to those obtained in qNSCs (Figures S5G and S5H). Moreover, no obvious change was obtained in autophagy levels (LC3-II/β-actin = 0.54), indicating that the prevention of changes in [Ca2+]ly can inhibit the change of autophagy level. Furthermore, FACS results implied that 23.2 ± 2.9% of qNSCs were transformed into aNSCs after stimulation by EGF and bFGF in the presence of VeRa for 2 days (n = 5) (Figure S5I). These results demonstrated that [Ca2+]ly changes had an obvious effect on lysosomal pH and the level of autophagy and further influences the activation of qNCSs.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging and Quantification of Lysosomal Ca2+ and pH in qNSCs and aNSCs

(A) Confocal fluorescence lifetime images of qNSCs and aNSCs collected from pH channel, Ca2+ channel, and overall channel. Scale bar: 10 μm.

(B) Lysosomal density scatter profiles of neural stem cells. The density plot was pseudo color, red and blue correspond to populations with higher and lower frequencies of occurrence. The data were obtained from 100 lysosomes in 10 cells.

(C) Confocal fluorescence lifetime images of qNSCs stimulated with EGF and bFGF. For comparison, the image of qNCSs stimulated by EGF and bFGF in the presence of bafilomycin A1 (Baf A), rapamycin (Rapa), and Rapa and VeRa was also obtained. Scale bar: 10 μm.

(D) Lysosomal density scatter profiles of qNSCs stimulated by bafilomycin A1, rapamycin, and rapamycin and VeRa. The density plot was pseudo color, here red and blue correspond to populations with higher and lower frequencies of occurrence. The data were obtained from 100 lysosomes in 10 cells.

(E–I) FACS sorting scheme used to isolate qNSCs and aNSCs. (E) qNCSs, (F) qNSCs and aNSCs after qNSCs were stimulated with EGF and bFGF, (G) EGF and bFGF in the presence of bafilomycin A1, (H) EGF and bFGF in the presence of rapamycin, (I) EGF and bFGF in the presence of rapamycin and VeRa.

(J) Immunoblotting analysis of relative levels of LC3-I, LC3-II in lysate purified from (i) qNSCs, (ii) aNSCs, (iii) qNSCs stimulated by Rapa, and (iv) qNSCs stimulated by Rapa in the presence of VeRa.

(K) The quantification of LC3-II/β-actin expression on western blot. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of five samples in each experimental group. Assume that the significance level of the statistical test is 0.001 (∗∗∗) (n = 20; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001).

(L) Schematic of rapamycin as an anti-aging agent.

On the other hand, we observed the activation ability of qNSCs by changing lysosomal pH. We found that, after the pH value of qNSCs was adjusted to 4.00, 35.8 ± 2.7% qNSCs (n = 5) were transformed into aNSCs. When lysosomal pH was increased to 4.45, the transformation ability of qNSCs into aNSCs showed the highest value of 50.1 ± 2.4%. More interestingly, after the lysosomal pH gradually increased from 4.45 to 6.00, the transformation ratio was decreased instead. When pH value was controlled to 6.00, the ability of qNSCs transferred into aNSCs was decreased down to 8.7 ± 0.5% (Figures S6A–S6I). Therefore, the activation ability of qNSCs transferred into aNSCs demonstrated the highest value at the optimized lysosomal pH of 4.45. Moreover, it was found that the degree of autophagy was also the highest (LC3-II/β-actin = 1.87 ± 0.06) at this pH value. When lysosome pH changed from 4.45 to 4.00 or 4.45 to 6.00, the autophagic level was significantly decreased (Figures S6J and S6K). These results demonstrated that lysosomal pH was significantly important to regulate the level of autophagy and then to affect the activation ability of qNSCs. Then, the results were further confirmed by addition of bafilomycin A1, which significantly prevented the decrease of pHly and increase of [Ca2+]ly in qNSCs. In addition, the level of autophagy in qNSCs was remarkably reduced (LC3-II/β-actin = 0.4). Only 14.7 ± 2.8% qNSCs were transformed into aNSCs (n = 5) (Figures 7E and 7G). These results strongly suggested that the regulation of lysosomal pH (0.5 pH) and Ca2+ concentration (580 ± 27 μM) is possibly to promote lysosomal activity, increase autophagy, and further regulate lysosomal-mediated qNSCs activation capacity.

It has been reported that aging has a close relationship with lysosomal activity, the ability of qNSCs activation, and the number of aNSCs. More importantly, although previous study has proved rapamycin (Rapa), an antiaging drug, has the ability of antiaging, the actual molecular mechanism of rapamycin-induced antiaging is still unclear (Laraia et al., 2019; Leeman et al., 2018; Rubinsztein et al., 2011). For this purpose, we next investigated the function of lysosome during rapamycin-induced antiaging. As shown in Figures 7C and 7H, after qNSCs were stimulated by EGF and bFGF in the presence of 10 nM Rapa for 2 days, 65.3 ± 6.0% qNSCs were transformed into aNSCs. At the same time, lysosomal pH was decreased to 4.62 ± 0.20, whereas lysosomal Ca2+ concentration was increased to 570 ± 28 μM (Figure 7D). Moreover, it was found that autophagy was enhanced by stimulation of qNSCs with EGF and bFGF in the presence of 10 nM Rapa (LC3-II/β-actin = 1.10 ± 0.04), proving Rapa contributed to the activity of lysosomes and the level of autophagy. To our surprise, after addition of VeRa, seldom decrease in pHly (4.80 ± 0.15) and no apparent increase in [Ca2+]ly (508 ± 23 μM) were observed. The results suggested that the level of autophagy was decreased after the addition of Vera (LC3-II/β-actin = 0.82 ± 0.01) and the ability of qNSCs transferred to aNSCs was also decreased to 51.9 ± 3.5% (n = 5) (Figures 7D and 7I), further indicating that inhibiting the change of the concentration of lysosomal Ca2+ can reduce the effect of Rapa. The data implied that rapamycin-induced antiaging can be regulated through promoting lysosomal activity. Since lysosomal activity is closely related to autophagy, we can conclude that the antiaging ability of rapamycin was realized by increasing autophagy level through regulating lysosomal pH and Ca2+ concentration (Figure 6L).

Meanwhile, the mathematical model for correlation among the concentration of Ca2+, pH value, and bioprocesses (aging and ant-aging) was also constructed. In this work, the transformation rate of qNSCs to aNCSs (denoted as α) over 45% was defined as “antiaging,” whereas α ≤ 45% was defined as “aging.” As shown in Figure S6L, when α changed from 45.0% to 50.1%, the lysosomal pH increased from 4.45 to 4.75, whereas the concentration of Ca2+ decreased from 580 to 480 μM. Thus, the composed area was defined as antiaging, recorded as “Zone 1.” On the other hand, when α decreased from 45.0% to 19.7%, the lysosomal pH varied in the range of 4.50–5.50, whereas the concentration of Ca2+ changed from 400 to 600 μM. The composed area (except for “Zone 1”) is defined as “aging,” and it is recorded as “Zone 0.” When the lysosomal pH was higher than 5.50 or lower than 4.45, as well as Ca2+ concentration was higher than 600 μM or lower than 400 μM, the cell was in an abnormal state. These findings provide new insights into the regulation of aging caused by decreased activation of neural stem cells.

Discussion

A single DNA-based FLIM reporter was developed for exploring the roles of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ in regulating autophagy, in which a new FLIM Ca2+ probe was designed and assembled onto a DNA nanostructure together with pH-responsive and lysosome-targeted molecules. The DNA nanostructure with precisely controllable size and shape enabled simultaneous determination of pH and Ca2+ at the same localization without FRET or cross talk. In addition, taking the advantages of FLIM, the developed nanoprobe showed high accuracy with high spatial resolution. More importantly, the assembled DNA reporter showed long-term structural stability, which was very beneficial for real-time imaging and biosensing of pH and Ca2+ in lysosomes.

Using this useful and powerful tool, it was found that lysosomal pH increased with decreasing concentration of Ca2+, whereas the concentration of Ca2+ went down with rising pH value. Both pH value and concentration of Ca2+ in lysosomes was discovered to regulate the autophagy. Furthermore, the experimental results suggested that Aβ-induced neuronal death resulted from autophagy abnormal, which was regulated by improving lysosomal pH and reducing Ca2+ concentration. Moreover, it was found that the transformation of qNSCs to aNSCs was regulated by autophagy and Rapa-induced antiaging was realized by improving the level autophagy through regulating lysosomal pH and Ca2+ concentration.

This work has systematically studied the roles of lysosomal pH and Ca2+ to regulate the autophagy, which gives a new insight into understanding autophagy-related processes such as neurodegenerative diseases and aging. More importantly, this study has provided a new methodology for real-time tracking and simultaneous determination of multiple substances in cells, even in organelles, based on stable DNA nanostructures with different shapes such as octahedron and cylindrical.

Limitations of the Study

The signal collection time of FLIM imaging method is longer than that of the fluorescence intensity-based imaging method. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an ultrafast imaging method in the future studies.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Yang Tian (ytian@chem.ecnu.edu.cn)

Materials Availability

All the materials necessary to reproduce this study are included in the manuscript and Supplemental Information.

Data and Code Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgment

The authors greatly appreciate the financial support from NSFC (21635003 and 21811540027). This work also was supported by Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (201701070005E00020) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019TQ0095).

Author Contributions

Y.T. designed the experiments, wrote the manuscript, and was responsible for the work. Z.L. and Z.Z. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 24, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101344.

Contributor Information

Zhichao Liu, Email: zcliu@chem.ecnu.edu.cn.

Yang Tian, Email: ytian@chem.ecnu.edu.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bagh M.B., Peng S., Chandra G., Zhang Z., Singh S.P., Pattabiraman N., Liu A., Mukherjee A.B. Misrouting of v-ATPase subunit V0a1 dysregulates lysosomal acidification in a neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disease model. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederbick A., Kern H.F., Elsässer H.P. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) is a specific in vivo marker for autophagic vacuoles. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1995;66:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K.A., Myers J.T., Swanson J.A. pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macropHages. J. Cell. Sci. 2002;115:599–607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.Y.-S., Shin H.R., Berdan C.A., Ford B., Ward C.C., Olzmann J.A., Zoncu R., Nomura D.K. Covalent targeting of the vacuolar H+-ATPase activates autophagy via mTORC1 inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:776–785. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z., Zhang Y., Xia K., Yan Q., Kong H., Zhang J., Zuo X., Shi J., Wang L., Zhu Y. Nanodiamond autophagy inhibitor allosterically improves the arsenical-based therapy of solid tumors. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4347. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06749-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B., Song X., Wang C., Kong X., Tang Y., Lin W. Dual site-controlled and lysosome-targeted intramolecular charge transfer-photoinduced electron transfer-fluorescence resonance energy transfer fluorescent probe for monitoring pH changes in living cells. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:4085–4091. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T., Hanaoka K., Koide Y., Ujita S., Takahashi N., Ikegaya Y., Matsuki N., Terai T., Ueno T., Komatsu T. Development of a far-red to near-infrared fluorescence probe for calcium ion and its application to multicolor neuronal imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:14157–14159. doi: 10.1021/ja205809h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erben C.M., Goodman R.P., Turberfield A.J. A self-assembled DNA bipyramid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6992–6993. doi: 10.1021/ja071493b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Wang P., Lu Y., Wang R., Zhou L., Zheng X., Li X., Piper J.A., Zhang F. Lifetime-engineered NIR-II nanoparticles unlock multiplexed in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotech. 2018;13:941–946. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E.M., Barrett C.F., Bultynck G., Shamah S.M., Dolmetsch R.E. The tumor suppressor eIF3e mediates calcium-dependent internalization of the L-type calcium channel CaV1.2. Neuron. 2007;55:615–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Sun S., Zhang L., Lu Y., Wu A., Cai C., Lin H. Red, green, and blue luminescence by carbon dots: full-color emission tuning and multicolor cellular imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:5360–5363. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K., Osakada Y., Takada T., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Lifetime regulation of the charge-separated state in DNA by modulating the oxidation potential of guanine in DNA through hydrogen bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12843–12846. doi: 10.1021/ja0475813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana V., Elson-Schwab I., Fulga T.A., Sharp K.A., Loewen C.A., Mulkearns E., Tyynelä J., Scherzer C.R., Feany M.B. Lysosomal dysfunction promotes cleavage and neurotoxicity of Tau in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M., Waguri S., Chiba T., Murata S., Iwata J.-I., Tanida I., Ueno T., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong B., Zhu A., Luo Y., Tian Y., Yu Y., Shi G. Sensitive and selective colorimetric visualization of cerebral dopamine based on double molecular recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1837–1840. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong B., Zhu A., Ding C., Zhao X., Li B., Tian Y. Carbon dot-based inorganic-organic nanosystem for two-photon imaging and biosensing of pH variation in living cells and tissues. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:5844–5848. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Jäättelä M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:886–897. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y.-H., Triggle D.J. Chiral aspects of drug action at ion channels: a commentary on the stereoselectivity of drug actions at voltage-gated ion channels with particular reference to verapamil actions at the Ca2+ channel. Ehirality. 1991;3:393–404. doi: 10.1002/chir.530030504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia L., Friese A., Corkery D.P., Konstantinidis G., Erwin N., Hofer W., Karatas H., Klewer L., Brockmeyer A., Metz M. The cholesterol transfer protein GRAMD1A regulates autophagosome biogenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:710–720. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman D.S., Hebestreit K., Ruetz T., Webb A.E., McKay A., Pollina E.A., Dulken B.W., Zhao X., Yeo R.W., Ho T.T. Lysosome activation clears aggregates and enhances quiescent neural stem cell activation during aging. Science. 2018;359:1277–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.aag3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang Y., Yang S., Zhao Y., Yuan L., Zheng J., Yang R. Hemicyanine-based high resolution ratiometric near-infrared fluorescent probe for monitoring pH changes in vivo. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:2495–2503. doi: 10.1021/ac5045498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Fang B., Jin M., Tian Y. Two-photon ratiometric fluorescence probe with enhanced absorption cross section for imaging and biosensing of zinc ions in hippocampal tissue and zebrafish. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:2553–2560. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Green A.A., Yan H., Fan C. Engineering nucleic acid structures for programmable molecular circuitry and intracellular biocomputation. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:1056–1067. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhu R., Chen K., Zheng H., Zhao H., Yuan C., Zhang H., Wang C., Zhang M. Potent and specific Atg8-targeting autophagy inhibitory peptides from giant ankyrins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:778–787. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Song P., Zhou G., Zuo X., Aldalbahi A., Lou X., Shi J., Fan C. Electrochemical detection of nucleic acids, proteins, small molecules and cells using a DNA-nanostructure-based universal biosensing platform. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1244–1263. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Dong H., Zhang L., Tian Y. Development of an efficient biosensor for the in vivo monitoring of Cu+ and pH in the brain: rational design and synthesis of recognition molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:16328–16332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Pei H., Zhang L., Tian Y. Mitochondria-targeted DNA nanoprobe for real-time imaging and simultaneous quantification of Ca2+ and pH in neurons. ACS Nano. 2018;12:12357–12368. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wang S., Li W., Tian Y. Bioimaging and biosensing of Ferrous ion in neurons and HepG2 cells upon oxidative stress. Anal. Chem. 2018;90:2816–2825. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Jing X., Zhang S., Tian Y. A copper nanocluster-based fluorescent probe for real-time imaging and ratiometric biosensing of calcium ions in neurons. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:2488–2497. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wu P., Yin Y., Tian Y. A ratiometric fluorescent DNA nanoprobe for cerebral adenosine triphosphate assay. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2019;55:9955–9958. doi: 10.1039/c9cc05046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio J.P., Pryor P.R., Bright N.A. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamiki T., Sekine T., Aiko M., Su S., Minami T. An organic FET with an aluminum oxide extended gate for pH sensing. Sens. Mater. 2019;31:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanaswamy N., Chakraborty K., Saminathan A., Zeichner E., Leung K., Krishnan Y. A pH-correctable, DNA-based fluorescent reporter for organellar calcium. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:95–102. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omen P., Aref M.A., Kaya I., Phan N.T.N., Ewing A.G. Chemical analysis of single cells. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:588–621. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W., Wang H., Yang L., Yu Z., Li N., Tang B. Ratiometric Fluorescence nanoprobes for subcellular pH imaging with a single-wavelength excitation in living cells. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:6743–6748. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampe D., Triggle D.J. New ligands for L-type Ca2+ channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:112–115. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90196-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D.C., Mariño G., Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M., Cai X., Hara M., Tojo S., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Anomalous fluorescence from the azaxanthone ketyl radical in the excited state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3702–3703. doi: 10.1021/ja043212v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C., Fraldi A., Medina D.L., Ballabio A. Signals from the lysosome: a control center for cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;14:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakova D.M., Cammer N.C., Huisman T.M., Verkhusha V.V., Hodgson L. Direct multiplex imaging and optogenetics of Rho GTPases enabled by near-infrared FRET. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:591–600. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D., Wang X., Li X., Zhang X., Yao Z., Dibble S., Dong X., Yu T., Lieberman A.P., Showalter H.D., Xu H. Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:731. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S.-L., Chen X.-P., Zhang X.-F., Miao J.-Y., Zhao B.-X. A rhodamine B-based lysosomal pH probe. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:919–925. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01763c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Qin Y., He Y., Huang Q., Fan C., Chen H.-Y. Functional nanoprobes for ultrasensitive detection of biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:4234–4243. doi: 10.1039/c000682n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa T., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Mechanistic insight into the TiO2 photocatalytic reactions: design of new photocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:5259–5275. [Google Scholar]

- Tang B., Yu F., Li P., Tong L., Duan X., Xie T., Wang X. A near-infrared neutral pH fluorescent probe for monitoring minor pH changes: imaging in living HepG2 and HL-7702 cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3016–3023. doi: 10.1021/ja809149g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Sun Y., Wu H., Pei J., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Wang L., Li B., Wang L., Shi J. Acupuncture promotes mTOR-independent autophagic clearance of aggregation-prone proteins in mouse brain. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19714. doi: 10.1038/srep19714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q., Chen S., Shi W., Li L., Ma H. Lysosomal pH rise during heat shock monitored by a lysosome-targeting near-infrared ratiometric fluorescent probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:10916–10920. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhao F., Li M., Zhang C., Shao Y., Tian Y. A SERS optophysiological probe for the real-time mapping and simultaneous determination of the carbonate concentration and pH value in a live mouse brain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:5256–5260. doi: 10.1002/anie.201814286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yao H., Li C., Shi H., Lan J., Li Z., Zhang Y., Liang L., Fang J.-Y., Xu J. HIP1R targets PD-L1 to lysosomal degradation to alter T cell–mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:42–50. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Klionsky D.J. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010;12:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Chen Y., Yu Z., Pan W., Wang H., Li N., Tang B. Dual-ratiometric fluorescent nanoprobe for visualizing the dynamic process of pH and superoxide anion changes in autophagy and apoptosis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface. 2017;9:27512–27521. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b08223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Beck T., Tan W. Design of a molecular beacon DNA probe with two fluorophores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:402–405. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010119)40:2<402::AID-ANIE402>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A., Qu Q., Shao X., Kong B., Tian Y. Carbon-dot-based dual-emission nanohybrid produces a ratiometric fluorescent sensor for in vivo imaging of cellular copper ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7185–7189. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.X., Tuo B., Yang J.J. The hills and valleys of calcium signaling. Sci. China. Life Sci. 2016;59:743–748. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-5098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.