Abstract

Treatment Escalation Plans (TEPs) are paper and electronic components of patients' clinical record that are intended to encourage patients and caregivers to contribute in advance to decisions about treatment escalation and de-escalation at times of loss of capacity. There is now a voluminous literature on patient decision-making, but in this qualitative study of British clinicians preparing to implement a new TEP, we focus on the ways that they understood it as much more than a device to promote patient awareness of the potential for pathophysiological deterioration and to elicit their preferences about care. Working through the lens of Callon's notion of agencements, and elements of May and Finch's Normalisation Process Theory, we show how clinicians saw the TEP as an organising device that enabled translation work to elicit individual preferences and so mitigate risks associated with decision-making under stress; and transportation work to make possible procedures that would transport agreed patterns of collective action around organisations and across their boundaries and to mitigate risks that resulted from relational and informational fragmentation. The TEP promoted these shifts by making possible the restructuring of negotiated obligations between patients, caregivers, and professionals, and by restructuring practice governance through promoting rules and resources that would form expectations of professional behaviour and organisational activity.

Keywords: UK, Awareness contexts, Goals of care, Performativity, Shared-decision-making, Status passage

Highlights

-

•

EoLC decision-making tools frame interaction processes in relational space.

-

•

Decision-making tools transport patient preferences across organisational space.

-

•

Agencement theory and Normalisation Process Theory work well together.

1. Introduction

An important problem for contemporary healthcare services concerns the ways in which patients and caregivers can be involved in decisions about their care. Ideas about patient-centredness in healthcare delivery have long relied on the notion that patients ought not to be passive recipients of care, but should have opportunities to participate in important decisions about their treatment (Nolte, 2017). For healthcare providers the problems that stem from this are fourfold. It calls for the development of techniques through which to elicit patient and caregiver preferences; the development of interactional strategies for shared decision-making; procedures for enacting those decisions and embedding them into everyday practice; and ways of communicating both decisions and practices across complex organisations. Much of current research around shared decision-making explores the ways that patient preferences about the practices and goals of care are elicited. We explore the role of Treatment Escalation Plans (TEPs). TEPs are paper and electronic components of the patient's clinical record that are intended to encourage patients to make decisions in advance about specific treatments, and record their preferences around treatment escalation and de-escalation at times of loss of capacity. They have a wider set of organisational purposes and effects. In particular, we explore ways that medical, nursing and other healthcare professionals in three British hospitals and primary and community healthcare providers of TEPs made sense of the value and purpose of a specific TEP, the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (Fritz et al., 2017), in its development phase. Our focus is therefore on the work that follows a decision, and how TEPs might take the form of devices that structure patient preferences, translate them into co-ordinated organisational practices, and transport them between different healthcare settings.

1.1. The role of treatment escalation plans

Ever since the germinal work of Glaser, Strauss and colleagues in the 1960s (Glaser and Strauss, 1965; Quint, 1967; Strauss, 1968), it has been clear that dying within the frame of Western medicine involves the interweaving of complex sets of processes. Importantly, dying has become a managed process formed around institutionally sanctioned and organisationally structured sets of communicative and relational practices (Field, 1989) and health professionals have found that the psychosocial as well as biological processes of dying have become the focus of different kinds of work organised around the individualisation of patient care (May, 1992). At the same time, recognition of the limits of medicine has meant that clinicians have acknowledged the futility and distressing consequences of some medical interventions at the end of life (Timmermans, 1999). Patients and caregivers have increasingly sought—and contested—some control over these processes through the promotion of advance care directives and clinical protocols that set out a person's general instructions for care (Sabatino, 2010). While patients may have mobilised advance care plans to shape decisions about dying according to their general preferences, their capacity to communicate their wishes about whether or not to continue with life sustaining treatments may be threatened by the physiological and cognitive consequences of pathophysiological deterioration.

Against the background of these complex social shifts and clinical problems, TEPs have been developed as one element of a constellation of tools that are used in different ways to ‘manage’ the processes of pathophysiological deterioration. Like Advance Care Directives and Plans, Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) orders, have come to be seen as important ways of avoiding sometimes futile clinical interventions in extremis (National Confidential Inquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2012). The aim of their developers has been to facilitate decision-making by patients, families and clinicians through providing clear guidance on handling complex and often distressing clinical decisions and processes of care. Much of the debate about TEPs has touched on their perceived usefulness in decision-making at end of life, but they do much more than this. They signify an important transition in the status of the patient. They make clear that acute pathophysiological deterioration that will affect decision-making capacity is a reasonable prospect.

The use of TEPs acknowledges that rescue and recovery are possible, but that these may be unlikely outcomes of treatment. They therefore provide opportunities for patients and families to share their preferences about the kinds of treatment they would like, if such circumstances arise, and are an important part of everyone's care. In the UK, early decisions about DNACPR status and advance planning about limits of care now form part of national recommendations by the UK Resuscitation Council and have informed the national dissemination of the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (Fritz et al., 2017). National Health Service (NHS) providers are now expected to implement procedures that enable people with life limiting conditions or illnesses that predispose to sudden deterioration or cardiorespiratory arrest to think ahead, consider, discuss and record patient-centred recommendations, not only about CPR but also other elements of emergency care and treatment (Pitcher et al., 2017). This reflects an international impulse to integrate patient preferences about treatment escalation and de-escalation into clinical practice. It draws on a wider body of initiatives that include Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (Fromme et al., 2012) in the USA; in Canada, the Medical Orders for Scope of Treatments (Rasooly et al., 1994), and in the UK, the Universal Form of Treatment Options (Fritz et al., 2013).

1.2. Theorising treatment escalation plans as work

This paper is drawn from a study of the development and implementation of a TEP in a British NHS Region. We wanted to understand the ways in which participants in this process made sense of the value and purpose of the TEP in advance of its implementation; the ways that participants in the study built ‘implicit models’ for the use of TEPs; and the ways that they anticipated the effects of enacting TEPs in practice. The analysis presented here is therefore focused on the ways that participants conceptualised TEPs as interventions in their pre-implementation phase. Our research was abductive in approach (Clarke, 2016; Tavory and Timmermans, 2014), and drew on insights from three theories. First, we drew on Normalisation Process Theory (May and Finch, 2009), which identifies, characterises and explains core mechanisms that motivate and shape work, through ‘organised and organising agency in the production and reproduction of the implementation, embedding (or not), and continuing integration of material practices’. (May and Finch, 2009: 449). It thus provided a way of understanding the work of implementing and using the TEP as distributed collective action and collaborative work. Second, we drew on Performativity Theory (Callon, 2008; D'Adderio, 2008). This provided a way of conceptualising what the work was about, and it framed TEPs as agencements, goal-directed ensembles of human and non-human actors characterised by distributed and ‘proactive responsibilities’ and governance (Callon, 2008: 41). Finally, we drew on awareness context theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1965), as a way of understanding the changing micro-level dynamics of interactions between professionals, patients and caregivers, as patients moved through status passages marked by changes in their capacity to participate in decisions about their care (Glaser and Strauss, 1971). This was configured alongside a wider programme of work. We undertook systematic reviews of studies of the implementation of advance care plans (Lund et al., 2015) and treatment escalation plans (Cummings et al., 2017). We also undertook a retrospective analysis of hospital records (patients' notes) to explore clinical decision-making and negotiations with patients and caregivers in the period leading up to death (Campling et al., 2018).

2. Study design and methods of Investigation

2.1. Study group and methods

The research was undertaken in (a) three British Hospital settings (NHS Foundation Trusts), and (b) geographically coterminous primary and community healthcare providers in an NHS Region. Between January 2017 and July 2018, key informants were recruited into the study according to a purposive sampling procedure. They were participants in the development phase of a locally co-designed TEP, or in the pre-implementation phase of a nationally sponsored TEP. Key informants were experienced health professionals with knowledge of the conditions in which TEPs would be employed and who would likely be involved in developing and implementing them. Interviews were conducted with key informants (n = 36). They are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key informants.

| Key Informants | NHS Trust A | NHS Trust B | NHS Trust C | Primary care & hospice | Ambulance Trust | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Consultants | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Junior Doctors | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Senior Nurses | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9 | |||

| General Practitioners | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Paramedics | 2 | 2 | |||||

| NHS England | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ReSPECT National Working Group | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Total | 36 |

Interview schedules were informed by Normalisation Process Theory (May and Finch, 2009). Interviews were between 25 and 60 minutes duration and were conducted by MM, SL and NC. They were audio-recorded and transcripts of these recordings comprised the formal data for analysis. In addition, SB, MM, SL, SD, CM and AR undertook participant and non-participant observation in workshops and meetings (n = 46) that explored the desirable content of a TEP and its potential implementation. All authors reviewed various documentary materials related to pre-implementation decision-making and processes in participating organisations.

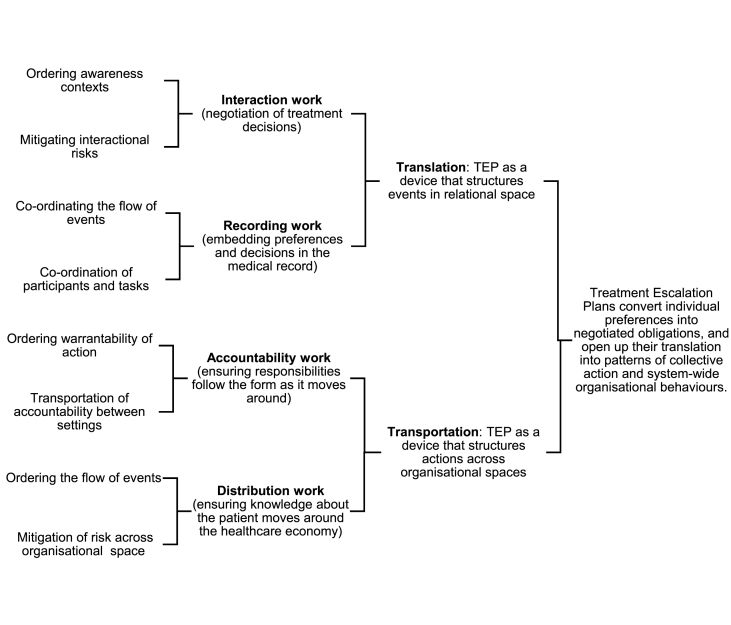

2.2. Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis focused on identifying, characterising and explaining participants' underlying implicit models of the work of treatment escalation planning and its effects. Informed by attribution theory (Fosterling, 2001; Martinko et al., 1996), this investigative approach involved structured analyses that sought to make robust inferences about sense-making (Weick et al., 2005) and anticipation (Tavory and Eliasoph, 2013). It was undertaken in three phases. First, interview transcripts were searched for attributions about the work of operationalising TEPs and attributions about the effects of TEPs on the organisation of care. Three kinds of attributions were identified, and these focused on: the strategic intentions underpinning the TEP (their purposes); the performative actions that stemmed from those intentions (the work associated with operationalising the TEP); and, the expected effects of those actions (the anticipated value of the TEP in practice). These formed a taxonomy of attributions. Second, components of the taxonomy were arranged in a model that mapped relations between elements of the data. Because this research was undertaken in the pre-implementation phase, this model characterises inferred components of an implicit ‘theory of use’ that characterised the purposes, value and effects of an anticipated TEP, and because the analysis was informed by Normalisation Process Theory, the question of purpose and value was linked to the kinds of work that stemmed from these. The model is shown in Fig. 1. Finally, the implicit theory of use generated by modelling components of participants' accounts were linked to relevant concepts of awareness context theory, status passage theory, and Normalisation Process Theory. This study was approved by the University of Southampton Research Ethics Committee (reference number 24886).

Fig. 1.

TEPs: purposes, practices, and effects.

3. From individual preferences to organisational processes

Although the purpose of a TEP is to help initiate a conversation between patients, carers and clinicians about how pathophysiological deterioration might be managed if their cognitive capacity is lost, and although our key informants greatly valued opportunities to have that conversation, their accounts emphasised the organisational implications of the TEP. They characterised this in two ways. The TEP mitigated the negative effects of fragmentation within the healthcare system by translating preferences into a plan for action; and it coordinated future action. In this context it seemed to solve structural, as well as individual problems. It is on this that our analysis of qualitative data focuses.

3.1. Mitigating the effects of systemic fragmentation

TEPs were framed as a means of shared decision-making with patients in anticipation of acute deterioration, but they have other effects too. They were seen to respond to an environment characterised by different operational pressures and systemic sources of fragmentation. TEPs are important because they frame work that responds to the structural demands of complex health services. This includes the co-ordination and legitimation of specific clinical decisions across organisational space, through institutionally sanctioned and formally defined ensembles of beliefs, behaviours and practices. Here, interactional practices are translated into the organisational routines of the hospital. These organisational routines are necessary to mitigate the systemic risks that arise out of the constant compression of time. These risks pressed hard on the work of junior doctors, as this one suggests.

L14 … I think it, you know, from the context of somebody who makes a reasonable number of these kind of decisions fairly acutely. It's quite nice to have a way of recording that fairly succinctly in a way that somebody else can then come along and say: oh, this has been discussed and these are the upshot of the discussions. I think it doesn't take very long to complete which is quite important (laughing) speaking from a point of view of somebody who never has time to complete all the forms and I think it's reasonably straight forward. And I think it will be perceived by people who are already making these decisions as a useful use of five minutes of their time to make sure it's recorded and it will then be passed on.

Attempts to speed up patient throughput and improve clinical workflow are associated with a policy push to minimise in-patient admissions and to reduce the length of hospital stays. For patients, caregivers, and health professionals this can lead to temporal fragmentation of care. Patients can experience multiple, relatively short, encounters with hospital services. Temporal fragmentation has its corollary in spatial fragmentation of care. If admitted, patients are often moved from location to location within and between wards and between and within hospital departments, and in and out of hospital. They may go home, back to a nursing home, or to some other destination depending on the nature and severity of their symptoms. Beyond the hospital they will be held in a network of care that includes family doctors, community nursing services, nursing home staff, and paramedics. For them, fragmentation was experienced as informational fragmentation. The TEP here was characterised as a device that could link domains of practice that were powerfully bounded off from each other. For this paramedic, like many other community health professionals, this was a major problem that could be solved by the introduction of a TEP.

L29 … there is a need for them [TEPs]. It would assist in the appropriate placement of patients. It would help with the speed with which decisions can be made, and that decisions are made in an informed way based on the completion of the document. So it assists with the flow. It assists with understanding.

Temporal and spatial fragmentation are compounded by relational fragmentation. Even within the hospital, complex technical divisions of labour amongst healthcare professionals, and the use of dynamic rostering to solve uneven allocation and availability of staff, mean that interactions between patients, caregivers and health professionals may be brief and superficial encounters in which they may not even learn the other's name. Even if they do, it is possible that they will never meet again. The effect of these fragmenting processes has been that knowledge about the patient has itself often become superficial, fragmented, and easily lost. In this context, as this consultant physician remarks, the TEP enables professionals and families to combine knowledge and timeliness.

P01 ... a patient's wishes about what they want to do and to happen, those are written very much from a hospital viewpoint or a primary care viewpoint (…) so when we read it in an emergency when we're stood at the foot of the bed of the patient, it's a case of ‘what were they meaning then’? And here I am at 43 the High Street on a cold and wet Thursday morning, how am I gonna do that? How do I make that happen when the G[eneral] P[ractitioner]'s aren't open? Why can't I access this acute ward without going through ED?

Health care services have responded to fragmentation in the organisation of hospital care by attempting to normalize into practice activities intended to manage and distribute knowledge about the patient, and to coordinate patient focused work. For this senior nurse, this was about ordering the spatial flow of events and responsibilities.

C82 … my patient work is out in the community and it was having patients that were being either brought into hospital or having things happen that they didn't want to happen because it wasn't clear at home—even if they had gone home for end of life [care], had a DNACPR [order] at home, they were still only going—being brought into ED because it wasn't clear to either out of hours GPs or paramedics, or ambulance staff, as to what the plan was for them. You know, if it wasn't clearly stated then they were left not quite knowing and particularly if you had families that were very anxious or (pause) weren't quite on board with ( …) what the patient wanted and the patient wasn't able to say.

These interventions focus on making and disseminating generalised information about the patient as a proxy for detailed relational knowledge of the person. This is true for most patients. Many will have previously experienced complex trajectories that have involved multiple encounters with hospital services, with frequent admissions to and through the emergency department. This is especially true of people with long-term conditions, often multi-morbid, who experience complex pathways through care characterised by episodes of potentially lethal symptom exacerbations.

3.2. Coordinating future action

Participants' accounts of TEPs revolved around their character as objects of practice, their perceived value, and their interactional workability. How, and how much, TEPs would be incorporated into routine practice, respondents said, would be determined by these factors. Here, the strategic intention of the TEP—as this was characterised by its developers—was to offer a mechanism for making and recording a point of decision at which pathophysiological deterioration was understood to be potentially irreversible, and then eliciting patients’ preferences about the course of future treatment if cognitive capacity to participate in those decisions was lost. It thus gives order to the patient and family awareness contexts, as this consultant physician suggests.

L29 … we'd always try and talk through generally if it's appropriate, talk through [the] kind of patient's wishes and so we would generate an urgent care plan (…) It's really useful to have that conversation with patients and families.

Patients and caregivers views were construed only as preferences. Neither patient nor family could demand that doctors and nurses took a particular course of action, and professionals were clear that they would always act in what they thought to be the patient's ‘best interests’. At the same time, participants in this study were deeply aware that the point of decision was cognitively and emotionally complex and that preferences, once elicited, were not fixed forever. It was possible that these could be treated as dynamic, and so the form could be revisited. While patient and family preferences could be regarded as dynamic, they were patients and their trajectories were complex. A junior doctor discussed the ways that the promise of co-ordinated action played a role in mitigating the interactional risk that followed from anxiety about the course of events to come.

K32 … the family are aware. They feel informed. They have time to ask questions. Has the value in releasing anxiety for the patients. The patient is aware and informed. And, again, so that it releases anxiety that if they were ill and came into hospital, perhaps out of hours, there would be a way of communicating with teams the pathways that are open for the patient.

It is important to note that these difficult conversations aimed at eliciting preferences focused on concrete possibilities. Again, co-ordination is central to this, but so too are the agreements that order the flow of events. A consultant physician told us that,

G01. I think [it's] going into the specifics about what could be or may or may not be appropriate, like you know ‘is referral to critical care appropriate’? I think that's actually quite useful because ‘do not resuscitate’ often gets misunderstood as ‘do not treat’ by some people (…) you know, may not be for resuscitation, but these are the things that are appropriate like antibiotics or non-invasive ventilation. But other things may not be, so this does allow a degree of tailoring for them patient.

At the centre of participants' accounts of their engagement with TEPs was its contribution to a complex interaction chain in which possible courses of action about future treatment were negotiated and recorded. This involves a network of actors in sets of decisions that are distributed across organisational time and space through interpersonal connections and relationships amongst participants in a decision (Rapley, 2008), and translated into emergent trajectories of care (Allen, 2018). The preference elicitation work of TEPs is thus oriented around a specific set of tasks. The first of these involves giving order to the process through which what Glaser and Strauss (1965) have called ‘awareness contexts’ are formed. These are the pattern of interactions and relationships that surround a patient who understands the implications of their illness and its likely outcomes—and their clinical trajectory. A specialist junior doctor told us that,

J19 ... [With] most of the patients we meet, we at least try to have the discussion about resuscitation, unless they had a particularly adverse reaction documented by someone else or it doesn't seem appropriate because they've come in for something completely irrelevant like, I don't know, a broken wrist or something so that they could go home again. Often if they are unwell we are trying to document how far we want to go with them. So, me and my team try to make sure it's at least documented so if someone else came, and we've already had those discussions, they can find it. I would say it's—it helps because it's summarised on a form which would mean you don't have to necessarily go through all the notes to find that specific discussion. [Part omitted] I suppose it covers a few bits that I don't necessarily talk about like dialysis and critical care because often I will have already said whether they're appropriate for everything or not. And if I've normally said that's ward based and just fluids and antibiotics, and not critical care or higher, that would cover our dialysis part as well in this hospital.

Ordering was conditional: it depended on the patient having capacity and being prepared to enter into the conversation with the doctor. But when the patient was willing and able to enter into the conversation, then this put in train two important things. It enabled the affective consequences of the patient's awareness context to be managed over time, and it suggested that a degree of control was possible over professional responses to pathophysiological processes. These are contexts where ‘acute decisions sometimes need to be made in a hurry [U04]’. Against this background an important purpose of the TEP was that it facilitated work to mitigate interactional risks that stem from uncertainty and anxiety about the patient's trajectory and its practical and affective consequences. In our earlier systematic reviews of implementation studies around advance care and treatment escalation plans (Cummings et al., 2017; Lund et al., 2015), we observed that clinicians' confidence in enacting them was diminished by the interactional risks derived from not honouring patients' wishes about care and this was present in participants' accounts in this study, too. This interactional risk resided in the ways in which structural forces at work in the healthcare system led back into the different kinds of fragmentation of care that we have discussed above, and that knowledge about the patient-as-person might itself be fragmented, incomplete, and poorly recorded. For this junior doctor, working the night shift, ‘the promise not honoured’ brought with it important relational risks, too.

L13 ... I think when you're deciding what to do at 3am it's useful to have it in black and white. Whereas I think when you leave it up to free text, you know, you're left interpreting what that free text means at 3am. And often, that will mean going back to the patient, or if the patient doesn't have capacity going back to the people who are mentioned on this form who are probably asleep at 3am (…) the response of people to being woke up at 3am to be asked the same set of questions that they have been asked before and to give the same set of responses will be quite frustrating, I imagine. And it may give the impression that they weren't listened to the first time or that we're just incompetent and haven't recorded it accurately. (…) Are we going to give antibiotics at all? Are we going to give IV hydration? Because they're often the difficult things to think about and if it's clearly documented (…) then that's really helpful.

Proponents of TEPs have emphasised the value of eliciting patient and family preferences about treatment and agreeing shared goals of care. These activities are important, but the work of identifying these preferences and translating them into a treatment plan also reflects the ways that knowledge and practice around the patient are structured in practice. In this context, patients and their families were constructed in these accounts as the beneficiaries of shared knowledge about preferences about treatment. The burden of decision-making in rapidly developing and stressful situations was lifted from family members too. This consultant physician understood the need to record them in a way that was easily accessible, and thus communicable, within and between clinical settings and the people who work in them, but which also reflected back in some way on what is known about the patient, and on what the patient knows.

L29 … It assists with the knowledge that the patients have had time and have been involved in those decisions. That, actually, somebody that knows the patient and the patient's illness have had time to speak to them and provide them with the options and the potential outcomes. It really assists with the nursing staff on the wards so that they know what is expected or what they can anticipate, and therefore how they can support the patient and the family. So that we're not ending up with people saying different things to the patient, so that's really, really, helpful.

The act of summarising the discussion—and the preferences, decisions and other elements that it encompasses—seems to effect the separation of preferences and decisions from those who made them, and constitute them as an organisational resource that demonstrates collective competence and institutional control over the situation. As it does so, it lays out the legitimacy of that process. It thus makes a set of anticipated actions both morally warrantable and interactionally workable, and this in turn seems to give the clinician confidence. It is assumed that the summary record reflects the patient's interactions with someone who knows them, and has had time to have a conversation with them. These are scarce interactional resources in the hospital, and the summary discussion stores them up so they can be found and used by others. The chain of interactions through which decisions are made, recorded and enacted become linked demonstrations of coordination and competence that mitigate relational risks. As it does this, it has further effects which are to order the flow of action over time and to ensure that action is itself timely. These mitigate interactional and relational risks at the point at which clinical decision-makers are confronted with an acute decision.

4. Discussion

A TEP crystallises the patient's preferences and offers them up as a guide to future action. In the accounts of our key informants, it opened up an organisational process. In Fig. 1, we have been able to account for the anticipated purpose, value and effects of the TEP through two forms of work:

-

a.

Translation work: the TEP could be used to elicit individual preferences and so mitigate risks associated with the negotiation and recording of treatment decisions when participants in the delivery of care are interacting with patients and families in conditions characterised by acute and stressful urgency. It offered a means by which those preferences could be translated into distributed accountabilities for collective action.

-

b.

Transportation work: the TEP could be used to mitigate risks associated with professional accountability and the distribution of knowledge and practice around the patient as they moved through the healthcare system. It could make possible procedures that would transport agreed patterns of collective action around organisations and across their boundaries.

These forms of work meant that the routine incorporation of the TEP into patient care was likely to reframe individual status passages within a shared set of assumptions about their management, and within common organisational processes. The volatile and unstable workflow in the hospital means that instabilities are continuously propagated. It comes as no surprise, then, to see that participants' accounts of translational and transportation work promoted a view of TEPs that emphasised their stabilising effects: using a TEP provides at least an opportunity to construct an orderly negotiation of awareness contexts, flow of events, and warrantable actions. These work together to secure the mitigation of very real relational and organisational risks. Here, the TEP is at the centre of an ensemble of beliefs, behaviours and practices that make possible the translation and transportation of preferences through different networks of actors. In relation to this, Callon (2008) has noted that, ‘any action is distributed’ and, whether the TEP is a paper form incorporated in a set of paper case notes, or a set of screens in an electronic health record, participants in this study anticipated that it would make possible complex and dynamic distributed sets of actions. It does this because it is what Callon has called an agencement, a goal-directed network of material artefacts and social practices that are mobilised by ‘proactive and responsible’ actors (Callon, 2008: 41), working together through collaborative projects. Indeed, the TEP—like many other kinds of procedural device employed by organisations—creates a project founded around different kinds of normative and relational expectations (Jensen, 2012). These include institutional, organisational, and personal accountabilities that are often poorly defined but have very real consequences. As Berkhout (2006) has argued, expectations are intrinsic to future action.

Translation and transportation were seen to dispose clinicians to different kinds of practical work. Interactional work was organised around focused discussions—structured by the form—with patients and families. But as we have noted above interactional work was only a small part of what followed from the anticipated purposes of the TEP. It was paralleled by recording work, in which preferences about treatment escalation and de-escalation were embedded in the patient record; by accountability work through which responsibilities were made manifest and followed the patient through their trajectories of care; and by distribution work in which information about preferences and the negotiations that led to them could be circulated amongst diverse participants in a complex patient career.

These forms of work meant that the routine incorporation of the TEP into patient care was likely to reframe individual status passages within a shared set of assumptions about their management, and within common organisational processes. Participants' implicit theories or mental models of the future TEP did not stop at translational and transportational patterns of work. They were also articulated to the ways that the TEP promoted a set of accountabilities for individuals and collectives. In this context, Normalisation Process Theory (May and Finch, 2009), points to the important role of work that builds the coherence of ensembles of behaviours and material practices as they are understood in the pre-implementation and implementation phases of the adoption and mobilisation of innovations in everyday work. Like Callon's (2008) notion of agencements, these ensembles require participants to do work that negotiates action and shapes wider patterns of restructuring that will shape the everyday capabilities of practitioners (May et al., 2016). Here, TEPs embodied a procedural response to a specific kind of ethical-clinical problem and converted it into a structured interaction and an organisational process. We can describe this, thus:

-

1)The Treatment Escalation Plan was defined in terms of its interactional workability. Here, ensembles of social practices were formed around material objects and their associated purposes. These were:

-

a)Relational Restructuring around a set of purposive interactions. These called for negotiated obligations between patients, caregivers, and professionals. Participants were defined in terms of their capabilities, and these were assumed to be relatively flexible;

-

b)Normative Restructuring around patterns of practice governance. These called for rules and resources that would form expectations of professional behaviour and organisational activity. Participants were defined in terms of their assumed accountabilities, and these were assumed to be relatively inflexible;

-

a)

-

2)

Individualising effects of TEP implementation were themselves anticipated as being translatable into collective action and organisational behaviour through the production of organising logics. These would be founded on agreements about the legitimacy of processes that would lead to shared decisions and open awareness contexts. These processes were formed around professionals' cognitive authority and the moral meanings that they assigned to their work.

Health professionals’ accounts of the anticipated utility of the TEP emphasised its capacity to support different kinds of work. We can interpret these forms of work as relational responses to the different kinds of fragmentation—temporal, spatial, relational and informational—that are experienced by patients, family members and clinicians as the patient moves through different pathophysiological states, individual status passages, and complex and dynamic organisational settings. Healthcare providers have limited capacity to solve these problems by relational means alone (Bridges et al., 2017), and in this context the TEP seems to form a means of overcoming the organisational impulses that lead to fragmentation.

Against the background of systemic fragmentation, the TEP forms both a structural and a cognitive resource that participants valued because of its anticipated moderating effects. Its’ use would give order to awareness contexts, the flow of events, and to patterns of professional and organisational accountability. As it does so, it would form a means of coordination, organising the possible flow of events, the participants and tasks that are associated with these events, and transports accountabilities between settings. Ordering and coordination would act together to mitigate risks—in interactions with the patient, family and other clinicians, and systemic risks within and between healthcare provider organisations. Here, the TEP could promote relational and normative restructuring within complex (and constantly changing) networks of actors, and relate this to an organising logic of care. Within this logic of care, the TEP was seen to create and mobilise a set of possible institutional obligations and to impose them on a whole system, rather than mere individuals.

5. Conclusion

An important purpose of the TEP is to facilitate a conversation about goals of care, and to form the basis for a shared decision between patients, families, and healthcare professionals. Such decisions are often emotionally charged and clinically complex. Importantly, they are often based on guesswork, for no-one can predict, precisely, the course of events that they represent. In this context, the interactional workability of the TEP as a preference elicitation tool is not its only important feature. The TEP offered other possibilities too. Clinicians’ characterised these through accounts of work that aimed to elicit patient and caregiver preference, and that has consequences that radiate outwards amongst individuals who must develop interactional strategies for shared decision-making and who must then enact those decisions. Their accounts radiate outwards, too, through procedures for embedding those decisions into everyday practice; and through ways of communicating both decisions and practices across complex organisations. Here, the TEP was constructed as a technical solution to a much bigger problem, the ways that dynamic complexity of activity within a hospital leads to multiple forms of fragmentation. As the effects of this complexity propagate through a healthcare service they multiply the interactional and systemic risks. The role of the TEP, therefore, is to act as a kind of organisational time-machine. It carries preferences forward into a coordinated future; and reflects those future actions into a past where they are explained and made warrantable. Thus, the anticipated purposes and value of the TEP are centrally important to the negotiation of a set of restructuring processes, in which the negotiated positions of patients, families and clinicians are identified, made workable, and integrated in an emergent trajectory for the patient as they travel through a pathophysiological process in a dynamic and emergent setting.

Funding

CRM, SB, NC, AC, SL, MM and AR were supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Wessex (NIHR CLAHRC Wessex) programme. SD was an independent patient representative in this study.

Funder's disclaimer

This paper presents independent work supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Credit Author Statement

Carl May: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - original draft; Visualisation; Supervision; Funding acquisition. Michelle Myall: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing; Supervision; Project administration. Susi Lund: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Natasha Campling: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Sarah Bogle Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Sally Dace: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - review & editing. Alison Richardson: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - original draft; Visualisation; Supervision; Funding acquisition

Acknowledgements

We thank the many health professionals who participated in this study, who must of necessity remain anonymous. We benefitted greatly from an enthusiastic and helpful PPI group. We also gratefully acknowledge the support and advice of the late Jim Watt and Mark Stafford-Watson, patient advisors to NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Wessex.

Earlier versions of this paper have been given at seminars of the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, October 2018); Green Templeton College (University of Oxford, January 2019); the Faculty of Medicine, University of Basel (April 2019), along with a plenary address at the Annual Conference of the Norwegian Health Services Research Association (Trondheim, March 2019). In addition, we greatly appreciated very helpful comments on the manuscript from Fiona Stevenson and Christine May.

Contributor Information

Carl May, Email: Carl.May@lshtm.ac.uk.

Michelle Myall, Email: m.myall@soton.ac.uk.

Susi Lund, Email: s.lund@soton.ac.uk.

Natasha Campling, Email: n.c.campling@soton.ac.uk.

Sarah Bogle, Email: s.j.bogle@soton.ac.uk.

Sally Dace, Email: s.dace@soton.ac.uk.

Alison Richardson, Email: alison.richardson@soton.ac.uk.

References

- Allen D. Analysing healthcare coordination using translational mobilization. J. Health Organisat. Manag. 2018;32(3):358–373. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-05-2017-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout F. Normative expectations in systems innovation. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2006;18(3-4):299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., May C., Fuller A., Griffiths P., Wigley W., Gould L., Libberton P. Optimising impact and sustainability: a qualitative process evaluation of a complex intervention targeted at compassionate care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017;26(12):970–977. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callon M. Economic markets and the rise of interactive agencements: from prosthetic agencies to habilitated agencies. pp29-56. In: Pinch T., Swedberg R., editors. Living in a Material World: Economic Sociology Meets Science and Technology Studies. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Campling N., Cummings A., Myall M., Lund S., May C.R., Pearce N.W., Richardson A. Escalation-related decision making in acute deterioration: a retrospective case note review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A.E. Anticipation work: abduction, simplification, hope, pp85-120. In: Bowker G.C., Timmermans S., Clarke A.E., Balka E., editors. Boundary Objects and beyond: Working with Leigh Star. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings A., Lund S., Campling N., May C.R., Richardson A., Myall M. Implementing communication and decision-making interventions directed at goals of care: a theory-led scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Adderio L. The performativity of routines: theorising the influence of artefacts and distributed agencies on routines dynamics. Res. Pol. 2008;37(5):769–789. [Google Scholar]

- Field D. Tavistock; London: 1989. Nursing the Dying. [Google Scholar]

- Fosterling F. Psychology Press; London: 2001. Attribution. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz Z., Malyon A., Frankau J.M., Parker R.A., Cohn S., Laroche C.M., Palmer C.R., Fuld J.P. The Universal Form of Treatment Options (UFTO) as an alternative to Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) orders: a mixed methods evaluation of the effects on clinical practice and patient care. PloS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz Z., Pitcher D., Regnard C., Spiller J., Wang M. ReSPECT is a personal emergency care plan summary. BMJ. 2017;357:j2213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2213. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme E.K., Zive D., Schmidt T.A., Olszewski E., Tolle S.W.J.J. POLST Registry do-not-resuscitate orders and other patient treatment preferences. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012;307(1):34–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1956. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A. Aldine; Chicago: 1965. Awareness of Dying. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd; London: 1971. Status Passage. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A. Arhus University Press; Aarhus: 2012. The Project Society (S. Moslund, Trans.) [Google Scholar]

- Lund S., Richardson A., May C. Barriers to advance care planning at end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PloS One. 2015;10(2):e0116629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinko M.J., Henry J.W., Zmud R.W. An attributional explanation of individual resistance to the introduction of information technologies in the workplace. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1996;15(5):313–330. [Google Scholar]

- May C. Individual care? Power and subjectivity in therapeutic relationships. Sociology. 1992;26(4):589–602. [Google Scholar]

- May C., Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–554. [Google Scholar]

- May C.R., Johnson M., Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement. Sci. 2016;11(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Confidential Inquiry into Patient Outcome and Death . Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; London: 2012. Time to Intervene? A Review of Patients Who Underwent Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation as a Result of An-Hospital Cardiorespiratory Arrest. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte E. Implementing person centred approaches. BMJ. 2017;358:j4126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher D., Fritz Z., Wang M., Spiller J.A.J.B. Emergency care and resuscitation plans. BMJ. 2017;356:j876. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint J. MacMillan; New York: 1967. The Nurse and the Dying Patient. [Google Scholar]

- Rapley T. Distributed decision making: the anatomy of decisions-in-action. Sociol. Health Illness. 2008;30(3):429–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasooly I., Lavery J.V., Urowitz S., Choudhry S., Seeman N., Meslin E.M., Lowy F.H., Singer P.A. Hospital policies on life-sustaining treatments and advance directives in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1994;150(8):1265–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino C.P. The evolution of health care advance planning law and policy. Milbank Q. 2010;88(2):211–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. The Sociology Press; San Fransisco: 1968. Anguish: the Case History of a Dying Trajectory. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory I., Eliasoph N. Coordinating futures: toward a theory of anticipation. Am. J. Sociol. 2013;118(4):908–942. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory I., Timmermans S. University of Chicago Press; Ill: 2014. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans S. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1999. Sudden Death and the Myth of CPR. [Google Scholar]

- Weick K.E., Sutcliffe K.M., Obstfeld D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ. Stud. 2005;16(4):409–421. [Google Scholar]