Summary

There is ongoing debate on how B cells contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). The success of B‐cell targeting therapies in MS highlighted the role of B cells, particularly the antibody‐independent functions of these cells such as antigen presentation to T cells and modulation of the function of T cells and myeloid cells by secreting pathogenic and/or protective cytokines in the central nervous system. Here, we discuss the role of different antibody‐dependent and antibody‐independent functions of B cells in MS disease activity and progression proposing new therapeutic strategies for the optimization of B‐cell targeting treatments.

Keywords: antibodies, B cells, B‐cell‐depleting therapies, multiple sclerosis

B cells can contribute to MS pathogenesis via production of antibodies against CNS antigens. The success of B‐cell targeting therapies in MS highlighted the antibody‐independent functions of B cells in MS. B cells can contribute to MS through antigen presentation to T cells and modulation of the function of T cells and myeloid cells by secreting pathogenic and/or protective cytokines.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen‐presenting cell

- CAAR

chimeric autoantibody receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DMF

dimethyl fumarate

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GA

glatiramer acetate

- GITRL

glucocorticoid‐induced tumor necrosis factor receptor‐ligand

- GM‐CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor

- IL‐21

interleukin‐21

- LT‐α

lymphotoxin α

- MHC‐II

major histocompatibility complex II

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- OCBs

oligoclonal bands

- PMN‐MDSCs

polymorphonuclear myeloid‐derived suppressor cells

- SPAG16

sperm‐associated antigen 16

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TACI

transmembrane activator and CAML interactor

- Tfh cell

follicular helper T cell

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Th17

T helper type 17

- TNF‐α

tumor necrosis factor α

- VLA‐4

very late antigen‐4

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that causes myelin loss and axonal damage leading to severe neurological disability commonly in young adults. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The disease course is initially relapsing–remitting for most individuals with MS (about 85% of patients), which is characterized by episodes of acute neurological dysfunction followed by full or partial recovery. Most individuals with relapsing–remitting MS develop secondary progressive MS after 10–20 years of disease evolution, a progressive course that is characterized by continuous neurological deterioration. Approximately, 10% of patients exhibit a progressive disease course from clinical onset, which is called primary progressive MS. The least common form of disease (<5%) is similar to primary progressive MS but with overlapping relapses and is called progressive relapsing MS. 5 Although the precise etiology of MS is unclear, CNS antigen‐specific T cells have been believed to have the key role in MS development. It is believed that following activation of these autoreactive T cells in the periphery through some infectious agents such as Epstein–Barr virus, which are molecular mimics of CNS antigens, they can enter the CNS and drive the inflammatory response leading to destruction of myelin and axon of nerve cells and formation of demyelinating plaques. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Studies have demonstrated that T‐cell receptors from MS patients can recognize both DRB1*1501‐restricted myelin basic protein peptide and DRB5*0101‐restricted Epstein–Barr virus peptide, and CD4+ T cells isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of MS patients specific for Epstein–Barr virus peptide, can cross‐recognize an immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide highlighting the key role of T cells in MS pathogenesis. 6 Correspondingly, therapeutic approaches for decades have aimed to limit effector T‐cell responses and most approved MS therapies have focused on targeting T cells or correcting the balance between effector and regulatory T‐cell responses. 11 , 12

Despite considerable evidence, such as infiltration of B cells in brain lesions and detectable oligoclonal bands (OCBs) in the CSF of approximately 90% of MS patients, which strongly suggests an involvement of B cells in MS, their role in MS has been underestimated and incompletely understood for decades. 13 , 14 Recently, an updated insight into the role of B cells in the immunopathogenesis of MS has emerged following the success of studies testing B‐cell‐depleting therapies with anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic approach, which suppressed inflammatory disease activity and limited new MS relapses. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Interestingly, these clinical studies have revealed that while T cells decrease after treatment with anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibodies, serum and CSF antibodies and long‐lived plasma cells remain unchanged, suggesting involvement of B cells in MS pathogenesis through antibody‐independent mechanisms such as antigen presentation to T cells and/or secretion of pro‐inflammatory or anti‐inflammatory cytokines. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 These findings triggered numerous investigations and debates among scientists regarding the different roles of B cells in MS pathogenesis and progression. In the following sections, we review the antibody‐dependent and antibody‐independent roles of B cells in MS and will discuss the mechanisms by which the clinical trial findings on different B‐cell‐depleting therapies can support basic investigations to delineate a concept for the role of B cells in MS.

The role of antibodies in MS

The involvement of B cells and antibodies in the pathogenesis of MS was demonstrated first by the discovery of OCB as a result of elevated IgG and IgM production in the CSF of individuals with MS. 25 , 26 The IgG OCBs can be found in approximately 90% of MS patients but IgM OCB can be found in only 30%–40% of patients, and are commonly associated with disease activity and therapeutic responses to B‐cell‐depleting therapy. 27 , 28 Elevated numbers of clonally expanded B cells and oligoclonal immunoglobulin bands in the CSF are common diagnostic hallmarks of multiple sclerosis. 29 By comparing the immunoglobulin transcriptomes of B cells with the corresponding immunoglobulin proteomes in the CSF of MS patients, Obermeier et al. demonstrated that the source of these intrathecally produced antibodies was the clonally expanded B cells in the CSF that can also be found in other CNS subcompartments such as meninges and parenchyma in the same patient but that differ among patients. 29 Studies have reported evidence for somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation of these B cells within the CSF. 30 , 31 Moreover intrathecal somatic hypermutation studies have shown the existence of identical B‐cell clones in the CNS and the periphery, indicating bidirectional trafficking of these B‐cell clones both into and out of the CNS. 32 , 33 , 34 This trafficking is regulated by chemoattractants such as CXCL10, CXCL12 and CXCL13, which have been shown to be elevated in the CSF of MS patients. 35

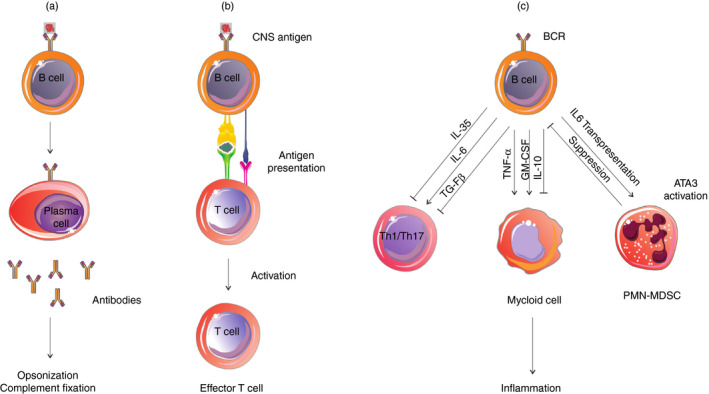

Further evidence for the involvement of antibodies in MS pathogenesis is provided by the identification of antibodies that bind to myelin fragments within phagocytes and also complement depositions in perivascular MS lesions. 36 , 37 Moreover, studies have shown that antibodies produced by clonally expanded plasma cells in the CSF of MS patients can bind to CNS tissue, causing complement‐mediated demyelination 38 , 39 (Fig. 1a). Some CNS auto‐antigens have been identified as targets for serum or CSF antibodies, including myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), myelin basic protein myelin‐derived lipids, neurofascin, contactin‐2, KIR4·1 and also some intracellular auto‐antigens such as DNA and RNA. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 Moreover, studies have identified antibodies of CSF OCBs that primarily recognize ubiquitous intracellular self‐proteins, suggesting that the generation of CSF OCBs might be as a response against dead‐cell debris. 48 , 49 Another target that has been identified for CSF autoantibodies in MS is sperm‐associated antigen 16 (SPAG16). 50 Increased plasma levels of anti‐SPAG16 antibodies with 95% specificity have been reported in 21% of MS patients and their seropositivity has been shown to be associated with an increased Expanded Disability Status Scale in MS patients and with an increased Progression Index in primary progressive MS. 51 , 52 It is believed that during CNS inflammation and astrocytic damage, the release of intracellular SPAG16 from astrocytes causes the formation of anti‐SPAG16 antibodies in the CNS, which can damage neurons through complement activation. 52 These findings confirm the role of B cells and antibody‐dependent CNS damage in MS disease severity and progression.

Figure 1.

Different roles of B cells in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. (a) B cells can differentiate into plasma cells and secrete autoantibodies that contribute to central nervous system (CNS) inflammation via opsonization of CNS antigens and complement fixation. (b) B cells can recognize and internalize the CNS antigens and act as antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) to activate CNS‐specific pathogenic T cells. (c) Different subsets of B cells in the CNS can modulate T‐cell and myeloid cell functions by secretion of pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokines. B cells also produce interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and present it in trans through their own IL‐6Rα, inducing Ly6G+ cell differentiation into polymorphonuclear myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (PMN‐MDSCs) and these MDSCs suppress B‐cell activation and cytokine production in a negative feedback loop.

However, despite remarkable investigations, the definition of different specific antigens in the CNS that can be recognized by CSF antibodies and the pathogenic roles of peripheral anti‐myelin antibodies in MS have been elusive. CNS‐specific antibodies in MS were conventionally believed to enhance demyelination in CNS tissue. 53 However, recent studies have indicated that peripheral anti‐myelin antibodies can activate peripheral myelin‐reactive T cells by opsonization of CNS antigens in deep cervical lymph nodes. 54 , 55 Overall, investigations are ongoing in this field to find the target antigens for different local and peripheral CNS‐specific antibodies to exactly describe the role of antibodies in MS.

The role of B cells as antigen‐presenting cells in MS

In addition to producing antibodies and secreting cytokines, B cells can also act as antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) (Fig. 1b). The APC capability of B cells has been demonstrated in many human diseases, such as infectious diseases and autoimmune diseases. 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 Disease‐relevant memory B cells in the spleen and lymph nodes of MS patients can act as very effective APCs by binding to specific antigens through their B‐cell receptor, internalizing and presenting them to CNS‐specific pathogenic T cells. Pathogenic T cells in MS and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) including T helper‐17 (Th17), T helper‐1 (Th1), follicular helper T (Tfh) and Tfh‐like cells are activated in the CNS‐draining lymph nodes, and B cells as APCs in cooperation with these T cells drive disease activity and progression in MS and EAE. Recently, we investigated the role of interleukin‐21 (IL‐21)‐producing T cells in MS and found that secretion of IL‐21 by Th17, Tfh and Tfh‐like cells can promote disease severity and progression, likely by helping B cells to produce antibodies and driving the inflammatory B‐cell response in the CNS, indicating the importance of T cell–B cell cooperation in MS pathogenesis. 60 , 61 The expression of co‐stimulatory CD80, CD86 and CD40 molecules by B cells can effectively induce activation, expansion and differentiation of CNS‐specific pathogenic T cells. Compared with professional APCs, B cells are more efficient at presenting protein antigens and appear to be the best APCs in low antigen concentrations as they can recognize neuroantigens by their specific receptor. 62 , 63

Compared with healthy individuals, in MS patients, most memory B cells have been demonstrated to be CNS antigen‐specific B cells, which can potently present myelin antigens, such as MOG and myelin basic protein to T cells and activate them. 64 , 65 Memory B cells have also been reported to be involved in antigen transportation to follicular dendritic cells in germinal centers. 20 In the interactions between APCs and T cells, co‐stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 play a pivotal role in T‐cell activation and proliferation. In comparison with the B cells of healthy individuals, higher expression of such co‐stimulatory molecules has been reported in B cells of MS patients, which can induce activation and proliferation of T cells in response to CNS antigens such as myelin basic protein. 66 The frequency of CD80+ B cells also has been shown to be abnormally increased in MS patients with active disease. 67 B cells in the CNS have been demonstrated to express co‐inhibitory molecules such as programmed death‐ligand 1 and glucocorticoid‐induced tumor necrosis factor receptor‐ligand (GITRL), which have a role in down‐regulation of T‐cell responses. 68 , 69 GITRL expression by B cells has been shown to induce differentiation of regulatory T cells. 69 In vivo studies in EAE mice also supported APC function of B cells. Mice with selective knockout of major histocompatibility complex II (MHC‐II) in B cells have been shown to be resistant to MOG‐induced EAE and to have diminished Th1 and Th17 responses. 58 , 70 Although B‐cell‐specific knocking out of MHC‐II causes a decrease of anti‐MOG production by EAE mice, anti‐MOG administration only partially restored EAE susceptibility, highlighting the MHC‐II‐dependent APC function of B cells in EAE. 58 Moreover, selective knockout of co‐stimulatory CD80 and CD86 genes in B cells has been shown to decrease T‐cell responses, highlighting the significant role of B‐cell–T‐cell interactions and APC functions of B cells in MS. 71 Overall, these findings confirm the concept that antigen‐specific B cells in the CNS can function as potent APCs in MS pathogenesis.

The role of cytokines secreted by B cells in MS

Numerous studies have reported the distinct cytokine profile of B cells and their abnormal pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokine balance in MS. 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 B cells of MS patients have been shown to produce abnormally high levels of IL‐6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF‐α), lymphotoxin α (LT‐α), and granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) compared with normal individuals. 72 , 75 , 77 , 78 Enhanced production of these pro‐inflammatory cytokines by B cells can activate other immune cells leading to disease progression (Fig. 1c). IL‐6 secreted by B cells can induce Th17 cell differentiation and conversely can inhibit differentiation of regulatory T cells. 79 , 80 Correspondingly, ablation of IL‐6‐producing B cells has been shown to result in reduced Th17 cell differentiation and EAE amelioration. 58 , 73 Both LT‐α and TNF‐α are pro‐inflammatory cytokines produced by B cells of MS patients in high amounts. 74 Overexpression of microRNA‐132 in B cells has been reported to play an important role in abnormally high production of LT‐α and TNF‐α by these cells in MS patients. 78 Bar‐Or et al. have shown that while B‐cell depletion using rituximab significantly diminishes pro‐inflammatory Th1 and Th17 responses, soluble products from activated B cells of untreated MS patients can reconstitute the reduced pro‐inflammatory T‐cell response, which appeared to be mainly mediated by LT‐α and TNF‐α secreted by B cells. 72

Studies also have demonstrated that B cells are capable of regulating immune responses by producing anti‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐10, IL‐35 and transforming growth factor‐β. 23 Interestingly, evidence from clinical trials has shown that B cells that reconstitute after B‐cell depletion therapy are different from the B cells of untreated patients and tend to produce high levels of anti‐inflammatory IL‐10 but low levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐6, TNF, LT and GM‐CSF and contribute to persistent tolerance. 73 , 74 , 77 Understanding how these reconstituting B cells lose their pro‐inflammatory characteristic and exert regulatory functions requires further investigation. Moreover, adoptive transfer of IL‐10‐secreting B cells has been reported to suppress EAE in an IL‐10‐dependent manner. 81 , 82 Consistently, Fillatreau et al. have shown that selective knocking out of B‐cell IL‐10 in mice increases EAE severity and prevents recovery from disease, suggesting the regulatory properties of B cells in EAE. 83

Alteration of the gut microbiome has also been reported to induce IL‐10‐producing B cells, resulting in decreased EAE severity. 84 By using IL‐10 reporter mice, Matsumoto et al. demonstrated that plasmablasts in the draining lymph nodes, but not splenic B cells, express IL‐10 and limit autoimmune inflammation, indicating the importance of plasmablasts as IL‐10‐producing regulatory B cells. 85 They also showed that interferon regulatory factor 4 could positively regulate IL‐10 production and inhibit the generation of pathogenic T cells by suppressing dendritic cell functions. Increased numbers of IL‐17‐ and interferon‐γ‐producing T cells have been found following suppression of these IL‐10‐producing regulatory B cells, demonstrating that these B cells can regulate the pathogenic T‐cell response in EAE. 83 Similar naive and memory B cells capable of secreting IL‐10 have also been described in humans. 75 , 86 , 87 IL‐10‐producing B cells generated from CD27+ memory B cells through Toll‐like receptors 4 and 9 stimulation (so called B10 cells) have been shown to inhibit production of TNF by monocytes through an IL‐10‐dependent route. 88 Human naive CD27– B cells have also been shown to produce IL‐10 following CD40 engagement. 72 , 74 , 78 , 89

B‐cell‐derived transforming growth factor‐β1 has also been shown to limit the early induction phase of EAE through inhibition of Th1/Th17 responses and dendritic cell APC activity. 90 IL‐35‐producing B cells have been reported that can suppress pro‐inflammatory immune responses in EAE, as it was observed that mice lacking IL‐35 production by only B cells was unable to recover from the T‐cell‐mediated EAE. 91 These IL‐35‐producing B cells can regulate immune responses through induction of IL‐10‐producing B cells, suggesting that IL‐35 can be used to induce regulatory B cells to treat autoimmune diseases. 92 Overall, understanding how different subsets of B cells serve a role in prevention or development of MS and how B‐cell targeting therapies affect different B‐cell functions can lead to the development of more specific therapeutics with better outcome and safety in the future.

The interactions between B cells and myeloid cells in MS

Myeloid cells, including monocytes, dendritic cells and microglia, play important roles in MS pathogenesis. Myeloid cells not only function as APCs to activate T cells, but also can produce cytokines and chemokines, which can affect other cells and inflammatory processes in the CNS. Recently several studies have demonstrated an intricate interaction between B cells and myeloid cells in MS.

Li et al. have reported increased frequencies of pro‐inflammatory GM‐CSF‐producing B cells in MS. 77 They showed that deletion of this subset of B cells resulted in a reduced pro‐inflammatory myeloid immune response in a GM‐CSF‐dependent manner, indicating that these B cells can enhance the myeloid cell inflammatory response by producing GM‐CSF implicating a pro‐inflammatory B‐cell/myeloid‐cell axis in MS. Moreover, they showed that signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) and STAT6 signaling were essential for B cells to produce GM‐CSF, and reciprocally regulate the generation of regulatory IL‐10‐secreting B cells. Conversely, Lehmann‐Horn et al. have shown that depletion of unactivated B cells causes enhanced production of pro‐inflammatory TNF by monocytes, resulting in EAE exacerbation. 93 Moreover, they showed that anti‐CD20 treatment increased the relative frequency of monocytes and production of TNF by these cells in individuals with neuroimmunological disorders, indicating that the TNF‐mediated pro‐inflammatory activity of monocytes might be controlled by a subset of B cells. These conflicting results indicate that more investigation in this field is needed to define the function of different subsets of B cells and suggest selective targeting of pathogenic B cells, which can be more safe and effective.

On the other hand, recently Knier et al. have described an interaction between a subset of IL‐6‐ and GM‐CSF‐producing B cells and polymorphonuclear myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (PMN‐MDSCs) in the CNS, which are linked in a negative feedback loop. They reported that Ly6G+ myeloid cells in the CNS of EAE mice can differentiate into PMN‐MDSCs and inhibit the recruitment, local proliferation and cytokine secretion of CD138+ pro‐inflammatory B cells, leading to recovery from EAE. They showed that Ly6G+ cells that were recruited to the CNS interacted physically with GM‐CSF‐ and IL‐6‐producing B cells and acquired the properties of PMN‐MDSCs in the CNS in a gp130‐STAT3‐dependent manner. They also reported that B cells can produce IL‐6 and present it in trans through their own IL‐6Rα, inducing Ly6G+ cell differentiation into MDSCs, which in turn would suppress B‐cell activation and cytokine production 94 (Fig. 1c). These results show that the interactions between myeloid cells, especially PMN‐MDSCs, and B cells may regulate B‐cell accumulation and cytokine production in the CNS of MS patients and therapeutic interventions targeting B‐cell/myeloid‐cell interactions might suppress CNS inflammation.

Targeting B cells in MS

B‐cell‐depleting therapies

The first B‐cell‐depleting clinical study testing rituximab, an anti‐CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody, as a therapeutic approach with the initial hypothesis of decreasing MS‐related pathogenic antibodies showed good efficacy, decreasing the CNS inflammation and limiting MS relapses. As plasma cells are CD20 negative and are not eliminated by anti‐CD20 therapy, the success of this approach updated the understanding about the role of B cells in MS and encouraged scientists to further investigate the antibody‐independent functions of B cells in MS such as antigen presentation and cytokine production. 17 After the success of a phase II trial of rituximab, scientists have focused on anti‐CD20 antibodies to optimize their efficacy and safety. In order to decrease the antibody response against anti‐CD20, a humanized anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, ocrelizumab, was developed and tested in a phase II trial with 600‐mg and 200‐mg doses, which showed 89% and 96% reduction in gadolinium‐enhancing lesions, respectively. 19 Moreover, the efficacy and safety of a fully humanized anti‐CD20 antibody, ofatumumab, has been evaluated in a phase II study, which showed suppression of new MRI lesion development while an antibody response against human anti‐CD20 antibodies was not seen in treated patients. 18

Conversely, a clinical study testing another B‐cell‐related therapy atacicept [a fusion protein of Transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI) and Fc fragment Of IgG which targets B cells and plasma cells but not memory B cells] resulted in adverse outcomes, suggesting memory B cells as a relevant disease‐promoting B‐cell subset and the existence of a functional heterogeneity among B cells and their capacity to be pathogenic or protective in MS. 95 In addition to involvement of B cells in the pathogenesis of relapsing–remitting MS, there is an ongoing debate about the involvement of these cells in primary progressive MS based on the results of a successful clinical study testing ocrelizumab in individuals with primary progressive MS (ORATORIO). 96 Studies have demonstrated the role of both systemic and compartmentalized inflammatory processes in MS pathogenesis. 2 , 97 , 98 Systemic inflammation, which mainly contributes to relapsing–remitting MS, involves activation of autoreactive T cells in the periphery and subsequent infiltration to the CNS where they can be reactivated and can damage neurons that correspond with focal inflammation, magnetic resonance imaging‐detectable lesions, and relapses while compartmentalized inflammation seems to contribute in the progressive form of MS and its exact process is not well understood. 97 , 98 , 99 Studies have shown that aggregates of B cells in the subarachnoid space play a key role in CNS‐compartmentalized inflammation. 97 , 98 , 99 As B‐cell depletion prevents the formation of the above‐mentioned focal CNS lesions, its therapeutic efficiency is assumed to be mainly based on the abrogation of the B‐cell properties in the periphery but it does not entirely stop chronic progression. 22 Nevertheless, ORATORIO findings showed that individuals with primary progressive MS experienced a modestly less severe worsening of disability compared with placebo‐treated patients, indicating the role of B cells in chronic non‐relapsing CNS‐compartmentalized inflammation that may underlie progressive tissue injury and worsening of disability in MS independent of focal inflammation. B cells may contribute to chronic progression by producing antibodies that cause complement‐mediated injury as well as through an abnormal pro‐inflammatory response mediated by cytokines produced by these cells. Moreover, B cells may contribute to chronic progressive tissue injury through secretion of products that may be directly toxic to oligodendrocytes and neurons in progressive MS. 100 , 101 Hence, these results may indicate the capability of anti‐CD20 therapy in managing progression independent of focal inflammation. Overall studies have focused on underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms by which B cells contribute to compartmentalized inflammation in the CNS and on clarifying the different pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory subsets of B cells to target them selectively to effectively treat MS.

Although the above‐mentioned different B‐cell‐depleting approaches are effective, the main trouble with these therapies is the elimination of all B cells, including pathogenic and non‐pathogenic B cells, which cause general immunosuppression and have some adverse effects. Hence, an ideal B‐cell‐directed therapy for autoimmune diseases such as MS should eliminate pathogenic autoimmune cells while sparing other B cells.

Ellebrecht et al. administered engineered human T cells expressing a chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR), which can bind to the B‐cell receptors of autoreactive B cells and eliminate them. These CAARs consist of desmoglein 3, a pemphigus vulgaris autoantigen, fused to CD137‐CD3ζ signaling domains. They showed that desmoglein 3 CAAR‐T cells were specifically cytotoxic against B cells expressing anti‐desmoglein 3 B‐cell receptors in vitro and in vivo. These findings show that CAAR‐T cells can be an effective strategy for targeting autoreactive B cells in other autoimmune diseases such as MS, which can be investigated in future studies. 102

The effects of other therapies on B cells in MS

Studies have demonstrated that other approved MS therapies that were primarily designed to suppress effector T‐cell responses can partially or indirectly affect B‐cell function (Table 1). For instance, interferon‐β, the first therapeutic that was approved for MS, has been shown to have anti‐inflammatory effects on different immune cells, such as T cells and myeloid cells, by regulating bystander responses and preventing their trafficking into the CNS. 103 , 104 Treatment with interferon‐β has been shown to reduce the percentages of C‐C chemokine receptor type 5‐positive and CD86‐positive naive B cells, resulting in reduction of co‐stimulatory signals and antigen presentation in MS patients. 105 Moreover, in MS patients treated with interferon‐β, the frequency of CD27+ memory B cells has been shown to reduce through induction of apoptosis. 106 Conversely, increased frequency of IL‐10‐producing regulatory B cells has been reported in the peripheral blood of patients treated with interferon‐β indicating a shift from pro‐inflammatory to anti‐inflammatory phenotype. 107

Table 1.

The effects of different multiple sclerosis treatments on B cells

| Drug | Effects on B cells | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anti‐CD20 |

↓ pre‐B cells, transitional B cells, naive B cells and memory B cells in blood ↓ B cells in CSF |

21, 73, 75, 77, 136 |

| Alemtuzumab (anti‐CD52) | ↓ B cells in blood | 138 |

| Daclizumab (anti‐CD25) |

↓ B cells in blood and CSF |

138, 139 |

| Natalizumab (anti‐α 4‐integrins) |

↓ B cells, plasma cells in CSF, IgM and IgG synthesis ↑ pre‐B cells, memory B cells and CXCR3+ B cells in blood |

125, 129, 140, 141 |

| Fingolimod (FTY720) |

↓ naive B cells, memory B cells, TNF, HLA‐DR and CD80 in blood ↑ transitional B cells in blood, TGF‐β, IL‐10 |

108, 109, 142, 143, 144 |

| Dimethyl fumarate |

↓ naive B cells and memory B cells in blood ↓ GM‐CSF, TNF, IL‐6 ↑ transitional B cells |

121, 122, 123, 124 |

| IFN‐β |

↓memory B cells in blood, IL‐12, CD80, CD40 ↑ transitional B cells in blood, TGF‐β, IL‐10 |

106, 145, 146, 147 |

| Teriflunomide | ↓ B cells in blood, B cell proliferation | 148, 149, 150, 151 |

| Glatiramer acetate |

↓ naive B cells, memory B cells and pre‐B cells in blood ↓LT‐α, ICAM‐1, IL‐6, immunoglobulin production ↑ IL‐10 |

119, 145, 152, 153 |

| atacicept (Anti‐BAFF/APRIL fusion protein) |

↓ transitional B cells, naive B cells, plasma cells and IgM in blood ↑ IL‐15 |

154, 155, 156, 157 |

| Mitoxantrone |

↑ B‐cell apoptosis; ↓ LT‐α; ↑ IL‐10 |

74, 158, 159, 160, 161 |

APRIL, A proliferation‐inducing ligand; BAFF, B‐cell‐activating factor; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GM‐CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; IL‐10, interleukin‐10; LT‐α, lymphotoxin‐α; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor‐β; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Treatment of MS patients with another compound, fingolimod, a modulator of sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor, has been shown to decrease total numbers of B cells in the circulation, especially memory B cells, but has little effect on CSF B cells. 108 , 109 , 110 Moreover, fingolimod markedly causes the cytokine profile to shift from a pro‐inflammatory toward an anti‐inflammatory phenotype. Fingolimod has also been reported to inhibit the formation of B‐cell aggregates in the meninges in an EAE model, but the numbers of plasma cells and infiltrating B cells was not altered in the CNS parenchyma. 111 Moreover, the migratory ability of regulatory B cells exposed to fingolimod has been demonstrated to be enhanced in vitro. 108

Glatiramer acetate (GA) is an FDA‐approved immunomodulatory drug that modulates encephalitogenic T‐cell responses by suppressing different immune cells such as pro‐inflammatory APCs, resulting in the development of Th2 cells. 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 Studies have shown that administration of GA in an EAE model increased the development of regulatory B cells. 117 , 118 Treatment of MS patients with GA causes an increase of IL‐10 and a decrease of IL‐6 and LT‐α production by B cells. 119 Moreover, GA has been shown to regulate the profile of adhesion molecules in B cells, inhibiting their migration into the CNS of individuals with relapsing–remitting MS. 120

Dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a new drug for MS treatment, is the methyl ester of fumaric acid, and its mechanisms of effect in MS are not clearly understood. Studies have shown that treatment of MS patients with DMF decreases the number of all peripheral B cells, especially memory B cells, through induction of apoptosis in these cells. 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 DMF has been shown to reduce production of IL‐6, GM‐CSF and TNF‐α by B cells and shift their cytokine profile towards a less pro‐inflammatory and more regulatory phenotype in vitro and in vivo. 121 , 123 , 124

Another efficacious therapeutic for MS, natalizumab, is a monoclonal antibody against the α 4 subunit of the integrin very late antigen‐4 (VLA‐4) that is expressed on most leukocytes, especially B and T cells. Natalizumab blocks the interaction of VLA‐4 with its ligand vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 on endothelial cells and prevents leukocyte infiltration into the CNS. Natalizumab has been shown to reduce the B‐cell frequency within the CNS tissue and CSF, and conversely increase their frequency in the peripheral blood of MS patients. 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 Intrathecal IgG production is also reduced and OCB may disappear after treatment with natalizumab. 129 , 130 The recurrence of disease activity after cessation of natalizumab treatment was attributed to memory B‐cell subsets, which are accumulated in the periphery during treatment. 126 , 127 Consistently, conditional deletion of VLA‐4 on B cells in the EAE model has been shown to prevent migration of B cells to the CNS and reduce disease severity, highlighting the role of B cells in MS pathogenesis. 131 As the migration of regulatory B cells into the CNS is also concomitantly blocked by natalizumab, 132 the exact effect of this agent on B cells and MS disease demands further investigation to clarify the role of different subsets of B cells in MS.

Alemtuzumab, is another FDA‐approved monoclonal antibody directed against CD52 for MS treatment. 133 , 134 Alemtuzumab treatment causes depletion of both T and B cells as well as some other leukocytes as CD52 is expressed at a lesser degree on monocytes and granulocytes. 135 Hyperpopulation of immature B cells in the relative absence of regulatory T cells and memory B cells has been reported following CD52 depletion, which causes secondary B‐cell autoimmunity and anti‐drug antibodies. 135 The effect of different MS therapies on B cells is described in Table 1.

Conclusion

The results of different B‐cell‐depleting therapies in MS patients demonstrated the existence of pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory subpopulations of B cells. Hence, the next strategy of B‐cell‐depleting therapy can be the application of anti‐CD20 along with an approach that can prevent the elimination of anti‐inflammatory B cells. Moreover, investigation and development of CAAR‐T cells, which can specifically target pathogenic autoreactive B cells, may provide an effective approach to avoid the adverse effects of B‐cell depletion with antibodies. Further clarifying the exact mechanisms by which different pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory subsets of B cells contribute to MS disease activity and progression, and understanding how these cells modulate T‐cell and myeloid cell functions in the CNS, and also development of biomarkers related to the function of different B‐cell subsets, will help clinicians to better optimize the different therapeutic modalities.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Dutta R, Trapp BD. Relapsing and progressive forms of multiple sclerosis – insights from pathology. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lassmann H. Multiple sclerosis pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018; 8:a028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gharibi T, Ahmadi M, Seyfizadeh N, Jadidi‐Niaragh F, Yousefi M. Immunomodulatory characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells and their role in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Cell Immunol. 2015; 293:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Afshar B, Khalifehzadeh‐Esfahani Z, Seyfizadeh N, Danbaran GR, Hemmatzadeh M, Mohammadi H. The role of immune regulatory molecules in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2019; 337:577061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klineova S, Lublin FD. Clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018; 8:a028928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen T. The role of EBV in MS pathogenesis. International MS Journal. 2006; 13:52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giovannoni G, Ebers G. Multiple sclerosis: the environment and causation. Curr Opin Neurol 2007; 20:261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005; 23:683–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gharibi T, Kazemi T, Aliparasti MR, Farhoudi M, Almasi S, Dehghanzadeh R et al Investigation of IL‐21 gene polymorphisms (rs2221903, rs2055979) in cases with multiple sclerosis of Azerbaijan, Northwest Iran. Am J Clin Exp Immunol. 2015; 4:7–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaskow BJ, Baecher‐Allan C. Effector T cells in multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018; 8:a029025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitz A, Singer E, Hafler D. Regulatory T cells: from discovery to autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018; 8:a029041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dobson R, Ramagopalan S, Davis A, Giovannoni G. Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndromes: a meta‐analysis of prevalence, prognosis and effect of latitude. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013; 84:909–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esiri MM. Multiple sclerosis: a quantitative and qualitative study of immunoglobulin‐containing cells in the central nervous system. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 1980; 6:9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bar‐Or A, Calabresi PA, Arnold D, Markowitz C, Shafer S, Kasper LH et al Rituximab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: a 72‐week, open‐label, phase I trial. Ann Neurol 2008; 63:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bar‐Or A, Grove RA, Austin DJ, Tolson JM, VanMeter SA, Lewis EW et al Subcutaneous ofatumumab in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: The MIRROR study. Neurology 2018; 90:e1805–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, Vollmer T, Antel J, Fox RJ et al B‐cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sorensen PS, Lisby S, Grove R, Derosier F, Shackelford S, Havrdova E et al Safety and efficacy of ofatumumab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2 study. Neurology 2014; 82:573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kappos L, Li D, Calabresi PA, O'Connor P, Bar‐Or A, Barkhof F et al Ocrelizumab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial. The Lancet. 2011; 378:1779–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Batista FD, Harwood NE. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cross AH, Stark JL, Lauber J, Ramsbottom MJ, Lyons J‐A. Rituximab reduces B cells and T cells in cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol 2006; 180:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. del Pilar Martin M, Cravens PD, Winger R, Kieseier BC, Cepok S, Eagar TN et al Depletion of B lymphocytes from cerebral perivascular spaces by rituximab. Arch Neurol 2009; 66:1016–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen P, Fillatreau S. Antibody‐independent functions of B cells: a focus on cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber MS, Hemmer B. Cooperation of B cells and T cells in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Mol Basis Mult Scler 2009; 51: 115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kabat EA, Freedman DA. A study of the crystalline albumin, gamma globulin and total protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of 100 cases of multiple sclerosis and in other diseases. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1950; 219:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Siritho S, Freedman MS. The prognostic significance of cerebrospinal fluid in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2009; 279:21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Villar LM, Casanova B, Ouamara N, Comabella M, Jalili F, Leppert D et al Immunoglobulin M oligoclonal bands: biomarker of targetable inflammation in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2014; 76:231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Villar LM, Sádaba MC, Roldán E, Masjuan J, González‐Porqué P, Villarrubia N et al Intrathecal synthesis of oligoclonal IgM against myelin lipids predicts an aggressive disease course in MS. J Clin Investig 2005; 115:187–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Obermeier B, Mentele R, Malotka J, Kellermann J, Kümpfel T, Wekerle H et al Matching of oligoclonal immunoglobulin transcriptomes and proteomes of cerebrospinal fluid in multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 2008; 14:688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beltran E, Obermeier B, Moser M, Coret F, Simo‐Castello M, Bosca I et al Intrathecal somatic hypermutation of IgM in multiple sclerosis and neuroinflammation. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 10):2703–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qin Y, Duquette P, Zhang Y, Talbot P, Poole R, Antel J. Clonal expansion and somatic hypermutation of VH genes of B cells from cerebrospinal fluid in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1998; 102:1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palanichamy A, Apeltsin L, Kuo TC, Sirota M, Wang S, Pitts SJ et al Immunoglobulin class‐switched B cells form an active immune axis between CNS and periphery in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:248ra106–248ra106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stern JN, Yaari G, Vander Heiden JA, Church G, Donahue WF, Hintzen RQ et al B cells populating the multiple sclerosis brain mature in the draining cervical lymph nodes. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:248ra107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. von Budingen HC, Kuo TC, Sirota M, van Belle CJ, Apeltsin L, Glanville J et al B cell exchange across the blood‐brain barrier in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2012; 122:4533–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blauth K, Owens GP, Bennett JL. The ins and outs of B cells in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 2015; 6:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Genain CP, Cannella B, Hauser SL, Raine CS. Identification of autoantibodies associated with myelin damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 1999; 5:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prineas JW, Graham JS. Multiple sclerosis: capping of surface immunoglobulin G on macrophages engaged in myelin breakdown. Ann Neurol. 1981; 10:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blauth K, Soltys J, Matschulat A, Reiter CR, Ritchie A, Baird NL et al Antibodies produced by clonally expanded plasma cells in multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid cause demyelination of spinal cord explants. Acta Neuropathol 2015; 130:765–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Elliott C, Lindner M, Arthur A, Brennan K, Jarius S, Hussey J et al Functional identification of pathogenic autoantibody responses in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain 2012; 135(Pt 6):1819–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brennan KM, Galban‐Horcajo F, Rinaldi S, O'Leary CP, Goodyear CS, Kalna G et al Lipid arrays identify myelin‐derived lipids and lipid complexes as prominent targets for oligoclonal band antibodies in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2011; 238:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Derfuss T, Parikh K, Velhin S, Braun M, Mathey E, Krumbholz M et al Contactin‐2/TAG‐1‐directed autoimmunity is identified in multiple sclerosis patients and mediates gray matter pathology in animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:8302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lalive PH, Menge T, Delarasse C, Della Gaspera B, Pham‐Dinh D, Villoslada P et al Antibodies to native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein are serologic markers of early inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:2280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lalive PH, Molnarfi N, Benkhoucha M, Weber MS, Santiago‐Raber ML. Antibody response in MOG35–55 induced EAE. J Neuroimmunol. 2011; 15:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lu F, Kalman B. Autoreactive IgG to intracellular proteins in sera of MS patients. J Neuroimmunol. 1999; 99:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mathey EK, Derfuss T, Storch MK, Williams KR, Hales K, Woolley DR et al Neurofascin as a novel target for autoantibody‐mediated axonal injury. J Exp Med 2007; 204:2363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Srivastava R, Aslam M, Kalluri SR, Schirmer L, Buck D, Tackenberg B et al Potassium channel KIR4.1 as an immune target in multiple sclerosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012; 367:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Warren KG, Catz I. Relative frequency of autoantibodies to myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1994; 121:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brandle SM, Obermeier B, Senel M, Bruder J, Mentele R, Khademi M et al Distinct oligoclonal band antibodies in multiple sclerosis recognize ubiquitous self‐proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113:7864–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Winger RC, Zamvil SS. Antibodies in multiple sclerosis oligoclonal bands target debris. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113:7696–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Somers V, Govarts C, Somers K, Hupperts R, Medaer R, Stinissen P. Autoantibody profiling in multiple sclerosis reveals novel antigenic candidates. J Immunol 2008; 180:3957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Bock L, Fraussen J, Villar LM, Álvarez‐Cermeño JC, Van Wijmeersch B, Van Pesch V et al Anti‐SPAG 16 antibodies in primary progressive multiple sclerosis are associated with an elevated progression index. Eur J Neurol 2016; 23:722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. de Bock L, Somers K, Fraussen J, Hendriks JJ, van Horssen J, Rouwette M et al Sperm‐associated antigen 16 is a novel target of the humoral autoimmune response in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2014; 193:2147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weber MS, Hemmer B, Cepok S. The role of antibodies in multiple sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Acta 2011; 1812:239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cserr HF, Knopf PM. Cervical lymphatics, the blood–brain barrier and the immunoreactivity of the brain: a new view. Immunol Today 1992; 13:507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kinzel S, Lehmann‐Horn K, Torke S, Hausler D, Winkler A, Stadelmann C et al Myelin‐reactive antibodies initiate T cell‐mediated CNS autoimmune disease by opsonization of endogenous antigen. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 132:43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li R, Rezk A, Li H, Gommerman JL, Prat A, Bar‐Or A. Antibody‐independent function of human B cells contributes to antifungal T cell responses. J Immunol 2017; 198:3245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Milich DR, Chen M, Schödel F, Peterson DL, Jones JE, Hughes JL. Role of B cells in antigen presentation of the hepatitis B core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:14648–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Molnarfi N, Schulze‐Topphoff U, Weber MS, Patarroyo JC, Prod’homme T, Varrin‐Doyer M et al MHC class II–dependent B cell APC function is required for induction of CNS autoimmunity independent of myelin‐specific antibodies. J Exp Med 2013; 210:2921–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Serreze DV, Fleming SA, Chapman HD, Richard SD, Leiter EH, Tisch RM. B lymphocytes are critical antigen‐presenting cells for the initiation of T cell‐mediated autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol 1998; 161:3912–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gharibi T, Hosseini A, Marofi F, Oraei M, Jahandideh S, Abdollahpour‐Alitappeh M et al IL‐21 and IL‐21‐producing T cells are involved in multiple sclerosis severity and progression. Immunol Lett 2019; 216:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gharibi T, Majidi J, Kazemi T, Dehghanzadeh R, Motallebnezhad M, Babaloo Z. Biological effects of IL‐21 on different immune cells and its role in autoimmune diseases. Immunobiology 2016; 221:357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pierce SK, Morris JF, Grusby MJ, Kaumaya P, Buskirk AV, Srinivasan M et al Antigen‐presenting function of B lymphocytes. Immunol Rev 1988; 106:149–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rivera A, Chen C‐C, Ron N, Dougherty JP, Ron Y. Role of B cells as antigen‐presenting cells in vivo revisited: antigen‐specific B cells are essential for T cell expansion in lymph nodes and for systemic T cell responses to low antigen concentrations. Int Immunol 2001; 13:1583–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Harp CT, Ireland S, Davis LS, Remington G, Cassidy B, Cravens PD et al Memory B cells from a subset of treatment‐naïve relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis patients elicit CD4+ T‐cell proliferation and IFN‐γ production in response to myelin basic protein and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:2942–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Harp CT, Lovett‐Racke AE, Racke MK, Frohman EM, Monson NL. Impact of myelin‐specific antigen presenting B cells on T cell activation in multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 2008; 128:382–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fraussen J, Claes N, Van Wijmeersch B, van Horssen J, Stinissen P, Hupperts R et al B cells of multiple sclerosis patients induce autoreactive proinflammatory T cell responses. Clin Immunol 2016; 173:124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Genc K, Dona DL, Reder AT. Increased CD80+ B cells in active multiple sclerosis and reversal by interferon β‐1b therapy. J Clin Investig 1997; 99:2664–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bodhankar S, Galipeau D, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. PD‐1 interaction with PD‐L1 but not PD‐L2 on B‐cells mediates protective effects of estrogen against EAE. Journal of Clinical & Cellular Immunology. 2013; 4:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ray A, Basu S, Williams CB, Salzman NH, Dittel BN. A novel IL‐10–independent regulatory role for B cells in suppressing autoimmunity by maintenance of regulatory T cells via GITR ligand. J Immunol 2012; 188:3188–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Weber MS, Prod'homme T, Patarroyo JC, Molnarfi N, Karnezis T, Lehmann‐Horn K et al B‐cell activation influences T‐cell polarization and outcome of anti‐CD20 B‐cell depletion in central nervous system autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 2010; 68:369–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. O’Neill SK, Cao Y, Hamel KM, Doodes PD, Hutas G, Finnegan A. Expression of CD80/86 on B cells is essential for autoreactive T cell activation and the development of arthritis. J Immunol 2007; 179:5109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bar‐Or A, Fawaz L, Fan B, Darlington PJ, Rieger A, Ghorayeb C et al Abnormal B‐cell cytokine responses a trigger of T‐cell–mediated disease in MS? Ann Neurol 2010; 67:452–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Barr TA, Shen P, Brown S, Lampropoulou V, Roch T, Lawrie S et al B cell depletion therapy ameliorates autoimmune disease through ablation of IL‐6–producing B cells. J Exp Med 2012; 209:1001–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Duddy M, Niino M, Adatia F, Hebert S, Freedman M, Atkins H et al Distinct effector cytokine profiles of memory and naive human B cell subsets and implication in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2007; 178:6092–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Duddy ME, Alter A, Bar‐Or A. Distinct profiles of human B cell effector cytokines: a role in immune regulation? J Immunol 2004; 172:3422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li R, Rezk A, Healy LM, Muirhead G, Prat A, Gommerman JL et al Cytokine‐defined B cell responses as therapeutic targets in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 2016; 6:626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Li R, Rezk A, Miyazaki Y, Hilgenberg E, Touil H, Shen P et al Proinflammatory GM‐CSF–producing B cells in multiple sclerosis and B cell depletion therapy. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:310ra166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miyazaki Y, Li R, Rezk A, Misirliyan H, Moore C, Farooqi N et al A novel microRNA‐132‐surtuin‐1 axis underlies aberrant B‐cell cytokine regulation in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2014; 9:e105421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M et al Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH 17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 2006; 441:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Korn T, Mitsdoerffer M, Croxford AL, Awasthi A, Dardalhon VA, Galileos G et al IL‐6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:18460–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2008; 118:3420–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yoshizaki A, Miyagaki T, DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, Kountikov EI et al Regulatory B cells control T‐cell autoimmunity through IL‐21‐dependent cognate interactions. Nature 2012; 491:264–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fillatreau S, Sweenie CH, McGeachy MJ, Gray D, Anderton SM. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL‐10. Nat Immunol. 2002; 3:944–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ochoa‐Reparaz J, Mielcarz DW, Haque‐Begum S, Kasper LH. Induction of a regulatory B cell population in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by alteration of the gut commensal microflora. Gut Microbes 2010; 1:103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Matsumoto M, Baba A, Yokota T, Nishikawa H, Ohkawa Y, Kayama H et al Interleukin‐10‐producing plasmablasts exert regulatory function in autoimmune inflammation. Immunity 2014; 41:1040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Blair PA, Norena LY, Flores‐Borja F, Rawlings DJ, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR et al CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Immunity 2010; 32:129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Rieger A, Bar‐Or A. B‐cell‐derived interleukin‐10 in autoimmune disease: regulating the regulators. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8:486–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Iwata Y, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, Dilillo DJ, Yanaba K, Venturi GM et al Characterization of a rare IL‐10‐competent B‐cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood 2011; 117:530–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Correale J, Farez M, Razzitte G. Helminth infections associated with multiple sclerosis induce regulatory B cells. Ann Neurol. 2008; 64:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Bjarnadottir K, Benkhoucha M, Merkler D, Weber MS, Payne NL, Bernard CC et al B cell‐derived transforming growth factor‐beta1 expression limits the induction phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Shen P, Roch T, Lampropoulou V, O'Connor RA, Stervbo U, Hilgenberg E et al IL‐35‐producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature 2014; 507:366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wang RX, Yu CR, Dambuza IM, Mahdi RM, Dolinska MB, Sergeev YV et al Interleukin‐35 induces regulatory B cells that suppress autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2014; 20:633–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lehmann‐Horn K, Schleich E, Hertzenberg D, Hapfelmeier A, Kümpfel T, von Bubnoff N et al Anti‐CD20 B‐cell depletion enhances monocyte reactivity in neuroimmunological disorders. J Neuroinflammation 2011; 8:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Knier B, Hiltensperger M, Sie C, Aly L, Lepennetier G, Engleitner T et al Myeloid‐derived suppressor cells control B cell accumulation in the central nervous system during autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2018; 19:1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kappos L, Hartung H‐P, Freedman MS, Boyko A, Radü EW, Mikol DD et al Atacicept in multiple sclerosis (ATAMS): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar‐Or A, Comi G et al Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:209–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, Moll NM, Roemer SF, Lassmann H et al Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:2188–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Magliozzi R, Howell OW, Reeves C, Roncaroli F, Nicholas R, Serafini B et al A gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010; 68:477–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Magliozzi R, Howell O, Vora A, Serafini B, Nicholas R, Puopolo M et al Meningeal B‐cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 2007; 130:1089–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lisak RP, Benjamins JA, Nedelkoska L, Barger JL, Ragheb S, Fan B et al Secretory products of multiple sclerosis B cells are cytotoxic to oligodendroglia in vitro . J Neuroimmunol 2012; 246:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lisak RP, Nedelkoska L, Benjamins JA, Schalk D, Bealmear B, Touil H et al B cells from patients with multiple sclerosis induce cell death via apoptosis in neurons in vitro . J Neuroimmunol 2017; 309:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ellebrecht CT, Bhoj VG, Nace A, Choi EJ, Mao X, Cho MJ et al Reengineering chimeric antigen receptor T cells for targeted therapy of autoimmune disease. Science 2016; 353:179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Galboiz Y, Shapiro S, Lahat N, Rawashdeh H, Miller A. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors as markers of disease subtype and response to interferon‐β therapy in relapsing and secondary‐progressive multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 2001; 50:443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Severa M, Rizzo F, Giacomini E, Salvetti M, Coccia EM. IFN‐β and multiple sclerosis: cross‐talking of immune cells and integration of immunoregulatory networks. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2015; 26:229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Niino M, Hirotani M, Miyazaki Y, Sasaki H. Memory and naive B‐cell subsets in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Lett 2009; 464:74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Rizzo F, Giacomini E, Mechelli R, Buscarinu MC, Salvetti M, Severa M et al Interferon‐β therapy specifically reduces pathogenic memory B cells in multiple sclerosis patients by inducing a FAS‐mediated apoptosis. Immunol Cell Biol 2016; 94:886–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Schubert RD, Hu Y, Kumar G, Szeto S, Abraham P, Winderl J et al IFN‐β treatment requires B cells for efficacy in neuroautoimmunity. J Immunol 2015; 194:2110–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Grützke B, Hucke S, Gross CC, Herold MV, Posevitz‐Fejfar A, Wildemann BT et al Fingolimod treatment promotes regulatory phenotype and function of B cells. Ann Clin Translat Neurol 2015; 2:119–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Miyazaki Y, Niino M, Fukazawa T, Takahashi E, Nonaka T, Amino I et al Suppressed pro‐inflammatory properties of circulating B cells in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod, based on altered proportions of B‐cell subpopulations. Clin Immunol 2014; 151:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kowarik M, Pellkofer H, Cepok S, Korn T, Kümpfel T, Buck D et al Differential effects of fingolimod (FTY720) on immune cells in the CSF and blood of patients with MS. Neurology 2011; 76:1214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bail K, Notz Q, Rovituso DM, Schampel A, Wunsch M, Koeniger T et al Differential effects of FTY720 on the B cell compartment in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 2017; 14:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Duda PW, Schmied MC, Cook SL, Krieger JI, Hafler DA. Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) induces degenerate, Th2‐polarized immune responses in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Investig 2000; 105:967–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Lalive PH, Neuhaus O, Benkhoucha M, Burger D, Hohlfeld R, Zamvil SS et al Glatiramer acetate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2011; 25:401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Neuhaus O, Farina C, Yassouridis A, Wiendl H, Bergh FT, Dose T et al Multiple sclerosis: comparison of copolymer‐1‐reactive T cell lines from treated and untreated subjects reveals cytokine shift from T helper 1 to T helper 2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97:7452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Vieira PL, Heystek HC, Wormmeester J, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. Glatiramer acetate (copolymer‐1, copaxone) promotes Th2 cell development and increased IL‐10 production through modulation of dendritic cells. J Immunol 2003; 170:4483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Weber MS, Starck M, Wagenpfeil S, Meinl E, Hohlfeld R, Farina C. Multiple sclerosis: glatiramer acetate inhibits monocyte reactivity in vitro and in vivo . Brain 2004; 127:1370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Begum‐Haque S, Christy M, Ochoa‐Reparaz J, Nowak EC, Mielcarz D, Haque A et al Augmentation of regulatory B cell activity in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by glatiramer acetate. J Neuroimmunol 2011; 232:136–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Begum‐Haque S, Sharma A, Christy M, Lentini T, Ochoa‐Reparaz J, Fayed IF et al Increased expression of B cell‐associated regulatory cytokines by glatiramer acetate in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 2010; 219:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Ireland Sara J, Guzman Alyssa A, O’Brien Dina E, Hughes Samuel, Greenberg Benjamin, Flores Angela et al The effect of glatiramer acetate therapy on functional properties of B cells from patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71:1421–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sellner J, Koczi W, Harrer A, Oppermann K, Obregon‐Castrillo E, Pilz G et al Glatiramer acetate attenuates the pro‐migratory profile of adhesion molecules on various immune cell subsets in multiple sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2013; 173:381–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Li R, Rezk A, Ghadiri M, Luessi F, Zipp F, Li H et al Dimethyl fumarate treatment mediates an anti‐inflammatory shift in B cell subsets of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2017; 198:691–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Longbrake EE, Cantoni C, Chahin S, Cignarella F, Cross AH, Piccio L. Dimethyl fumarate induces changes in B‐and T‐lymphocyte function independent of the effects on absolute lymphocyte count. Mult Scler J 2018; 24:728–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Lundy SK, Wu Q, Wang Q, Dowling CA, Taitano SH, Mao G et al Dimethyl fumarate treatment of relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis influences B‐cell subsets. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2016; 3:e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Smith MD, Martin KA, Calabresi PA, Bhargava P. Dimethyl fumarate alters B‐cell memory and cytokine production in MS patients. Ann Clin Translat Neurol 2017; 4:351–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Krumbholz M, Meinl I, Kümpfel T, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. Natalizumab disproportionately increases circulating pre‐B and B cells in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2008; 71:1350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Mellergård J, Edström M, Jenmalm MC, Dahle C, Vrethem M, Ernerudh J. Increased B cell and cytotoxic NK cell proportions and increased T cell responsiveness in blood of natalizumab‐treated multiple sclerosis patients. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e81685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Planas R, Jelčić I, Schippling S, Martin R, Sospedra M. Natalizumab treatment perturbs memory‐and marginal zone‐like B‐cell homing in secondary lymphoid organs in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42:790–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Stüve O, Youssef S, Weber MS, Nessler S, von Büdingen H‐C, Hemmer B et al Immunomodulatory synergy by combination of atorvastatin and glatiramer acetate in treatment of CNS autoimmunity. J Clin Investig 2006; 116:1037–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Warnke C, Stettner M, Lehmensiek V, Dehmel T, Mausberg AK, Von Geldern G et al Natalizumab exerts a suppressive effect on surrogates of B cell function in blood and CSF. Mult Scler J 2015; 21:1036–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. von Glehn F, Farias AS, de Oliveira ACP, Damasceno A, Longhini ALF, Oliveira EC et al Disappearance of cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal bands after natalizumab treatment of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler J 2012; 18:1038–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Lehmann‐Horn K, Sagan SA, Bernard CC, Sobel RA, Zamvil SS. B‐cell very late antigen‐4 deficiency reduces leukocyte recruitment and susceptibility to central nervous system autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 2015; 77:902–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Lehmann‐Horn K, Sagan SA, Winger RC, Spencer CM, Bernard CC, Sobel RA et al CNS accumulation of regulatory B cells is VLA‐4‐dependent. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2016; 3:e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL, Confavreux C, Fox EJ, Hartung H‐P et al Alemtuzumab versus interferon β1a as first‐line treatment for patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2012; 380:1819–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Coles AJ, Twyman CL, Arnold DL, Cohen JA, Confavreux C, Fox EJ et al Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease‐modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2012; 380:1829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Baker D, Herrod SS, Alvarez‐Gonzalez C, Giovannoni G, Schmierer K. Interpreting lymphocyte reconstitution data from the pivotal phase 3 trials of alemtuzumab. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74:961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Studer V, Rossi S, Motta C, Buttari F, Centonze D. Peripheral B cell depletion and central proinflammatory cytokine reduction following repeated intrathecal administration of rituximab in progressive Multiple Sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2014; 276:229–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Thomas K, Eisele J, Rodriguez‐Leal FA, Hainke U, Ziemssen T. Acute effects of alemtuzumab infusion in patients with active relapsing–remitting MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2016; 3:e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Lin YC, Winokur P, Blake A, Wu T, Romm E, Bielekova B. Daclizumab reverses intrathecal immune cell abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Translat Neurol 2015; 2:445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Wynn D, Kaufman M, Montalban X, Vollmer T, Simon J, Elkins J et al Daclizumab in active relapsing multiple sclerosis (CHOICE study): a phase 2, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, add‐on trial with interferon beta. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9:381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Saraste M, Penttilä T‐L, Airas L. Natalizumab treatment leads to an increase in circulating CXCR3‐expressing B cells. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2016; 3:e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Putzki N, Baranwal MK, Tettenborn B, Limmroth V, Kreuzfelder E. Effects of natalizumab on circulating B cells, T regulatory cells and natural killer cells. Eur Neurol 2010; 63:311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Nakamura M, Matsuoka T, Chihara N, Miyake S, Sato W, Araki M et al Differential effects of fingolimod on B‐cell populations in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 2014; 20:1371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Blumenfeld S, Staun‐Ram E, Miller A. Fingolimod therapy modulates circulating B cell composition, increases B regulatory subsets and production of IL‐10 and TGFβ in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Autoimmun 2016; 70:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Miyazaki Y, Niino M, Takahashi E, Suzuki M, Mizuno M, Hisahara S et al Fingolimod induces BAFF and expands circulating transitional B cells without activating memory B cells and plasma cells in multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 2018; 187:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Hussien Y, Sanna A, Söderström M, Link H, Huang Y‐M. Multiple sclerosis: expression of C D1a and production of IL‐12 p70 and IFN‐γ by blood mononuclear cells in patients on combination therapy with IFN‐β and glatiramer acetate compared to monotherapy with IFN‐β . Mult Scler J 2004; 10:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Rep MH, Schrijver HM, van Lopik T, Hintzen RQ, Roos MT, Adèr HJ et al Interferon (IFN)‐β treatment enhances CD95 and interleukin 10 expression but reduces interferon‐γ producing T cells in MS patients. J Neuroimmunol 1999; 96:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Rudick RA, Cookfair DL, Simonian NA, Ransohoff RM, Richert JR, Jacobs LD et al Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in a phase III trial of Avonex®(IFNβ‐1a) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 1999; 93:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Bar‐Or A, Freedman MS, Kremenchutzky M, Menguy‐Vacheron F, Bauer D, Jodl S et al Teriflunomide effect on immune response to influenza vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2013; 81:552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Bar‐Or A, Pachner A, Menguy‐Vacheron F, Kaplan J, Wiendl H. Teriflunomide and its mechanism of action in multiple sclerosis. Drugs 2014; 74:659–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Bar‐Or A, Wiendl H, Miller B, Benamor M, Truffinet P, Church M et al Randomized study of teriflunomide effects on immune responses to neoantigen and recall antigens. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2015; 2:e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Gandoglia I, Ivaldi F, Laroni A, Benvenuto F, Solaro C, Mancardi G et al Teriflunomide treatment reduces B cells in patients with MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammat 2017; 4:e403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Salama HH, Hong J, Zang YC, El‐Mongui A, Zhang J. Blocking effects of serum reactive antibodies induced by glatiramer acetate treatment in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2003; 126:2638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Blanco Y, Moral E, Costa M, Gómez‐Choco M, Torres‐Peraza J, Alonso‐Magdalena L et al Effect of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) on the immunophenotypic and cytokine profile and BDNF production in multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal study. Neurosci Lett 2006; 406:270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Dall'Era M, Chakravarty E, Wallace D, Genovese M, Weisman M, Kavanaugh A et al Reduced B lymphocyte and immunoglobulin levels after atacicept treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicenter, phase Ib, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalating trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:4142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Ma N, Xing C, Xiao H, He Y, Han G, Chen G et al BAFF suppresses IL‐15 expression in B cells. J Immunol 2014; 192:4192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Munafo A, Priestley A, Nestorov I, Visich J, Rogge M. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atacicept in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Van Vollenhoven R, Kinnman N, Vincent E, Wax S, Bathon J. Atacicept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase II, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:1782–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Chan A, Weilbach F, Toyka K, Gold R. Mitoxantrone induces cell death in peripheral blood leucocytes of multiple sclerosis patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2005; 139:152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Fox EJ. Mechanism of action of mitoxantrone. Neurology 2004; 63(suppl 6):S15–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Vogelgesang A, Rosenberg S, Skrzipek S, Bröker B, Dressel A. Mitoxantrone treatment in multiple sclerosis induces TH2‐type cytokines. Acta Neurol Scand 2010; 122:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Watson CM, Davison AN, Baker D, O'Neill JK, Turk JL. Suppression of demyelination by mitoxantrone. Int J Immunopharmacol 1991; 13:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]