Abstract

Background: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASP) have been widely implemented in hospitals to improve antimicrobial use and prevent resistance. However, the role of ASP in the emergency department (ED) setting is not well defined. Objective: The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of an ASP pharmacist culture review service in an ED. Methods: This was a retrospective, quasi-experimental study of all patients discharged from the ED with a positive culture. Patients discharged from the ED from February 1, 2015 to October 31, 2015 were managed by ED providers (pre-ASP), and those discharged from February 1, 2016 to October 31, 2016 were managed by a pharmacist-driven ASP (post-ASP implementation). The primary outcome was median time to change of antibiotic(s) in patients with inadequate antimicrobial therapy based on culture results. Secondary outcomes included time to culture evaluation, appropriateness of antimicrobials, and 30-day readmissions. Results: A total of 790 patients were included in the analysis (398 in pre-ASP group vs 392 in post-ASP implementation group). Median time to modification of inadequate antibiotic therapy decreased from 6.79 days in the pre-ASP group to 1.99 days in the post-ASP implementation group (P < .0001). Median time to culture review decreased in the post-ASP implementation group from 9.83 to 0.32 days (P < .0001). Appropriateness of culture-guided therapy increased in the post-ASP implementation group from 85.7 to 91.8% (P = .047). The rate of combined ED revisits and hospital readmissions was similar between groups (P = .367). Conclusion: ASP pharmacist evaluation of positive cultures in the ED was associated with a significant decrease in the time to appropriate therapy in patients discharged with inadequate therapy and higher rates of appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Keywords: anti-infectives, clinical services, infectious diseases, physician prescribing

Introduction

Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASP) have been implemented in a variety of patient care settings as a result of regulations published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Joint Commission.1-3 These programs have traditionally been hospital-based and enhance patient safety, reduce inappropriate antimicrobial use, and prevent antimicrobial resistance.4,5 In contrast to the 33 million annual hospital admissions in community hospitals, there were over 135 million emergency department (ED) visits in community hospitals in 2014.6 Antimicrobials are prescribed by ED practitioners at 11.4% of all ED visits, with respiratory tract, skin and soft tissue, and urinary tract infections being the most common infections encountered.7

ED practitioners are faced with many obstacles such as high patient volume, limited patient history, diagnostic uncertainty, varying levels of acuity, and the need for quick decision-making.8 This may lead to the overprescribing of antimicrobials, inadequate antimicrobial selection and dosing, adverse drug events, and drug interactions.9,10 Studies have found that antimicrobials account for roughly 19.3% of drug-related adverse events, which increase morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.11 Additionally, when finalized microbial culture results are reported after the patient has been discharged, there is potential for a lapse in continuity of care. Last, even with guideline-concordant prescribing patterns, there will be culture results that require modification due to resistance to empiric therapy. Each of these factors highlights the importance of antimicrobial stewardship activities in the ED.12-14

To date, the available data on culture review services in the ED are generally limited to institutions with dedicated ED clinical pharmacists.15-23 Although some programs have reported reduced hospital admissions and ED revisits with pharmacist involvement in antibiotic selection, they have not routinely seen improvement in empiric therapy selection.15-17 Furthermore, all of these studies were performed in large academic or tertiary medical centers. Thus, the design and outcomes of these studies may not be feasible in hospitals with limited pharmacy resources.

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of an ASP pharmacist culture review service in an ED in a small community hospital and evaluate the time to positive culture review and time to appropriate antimicrobials before and after a pharmacist-led ASP intervention. We hypothesized that clinically meaningful ASP efforts can be carried out in EDs without dedicated ASP pharmacists.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Patient Population

This was a retrospective, quasi-experimental study conducted at a 231-bed community hospital with an average of 26,000 ED visits each year. All patients who were discharged from the ED with a positive culture from any source were considered in the analysis. Patients were identified by querying an infection prevention database (Sentri7; Bellevue, Washington, USA) for positive cultures collected in the ED, followed by a manual review of electronic medical records. Patients were included if they were between 18 and 89 years of age and discharged from the ED to the outpatient setting (ie, home, assisted living, skilled or long-term care nursing facility). Patients were excluded if they were prisoners or wards of the state, pregnant, transferred from the ED to inpatient status, or discharged to another acute care facility. This study was approved by the university and hospital institutional review boards.

Follow-up of positive cultures for patients evaluated in the ED between February 1, 2015 and October 31, 2015 were managed by ED practitioners and nursing staff (pre-ASP). During this time period, there was no defined system for how positive cultures were communicated, evaluated, or documented. The laboratory department notified an ED nurse of cultures considered “critical results,” including multidrug resistant bacteria or blood cultures with microbiological growth. ED practitioners continued or modified antimicrobial regimens at their discretion. If therapy was modified, the ED practitioner would choose an alternative agent and a nurse would communicate with the patient and add an addendum to the patient’s electronic medical record.

Patients who were seen between February 1, 2016 and October 31, 2016 with positive cultures were evaluated by an ASP pharmacist (post-ASP implementation). Positive cultures were evaluated on a daily basis approximately 98% of the time during the study period. Each of the 3 pharmacists involved in making recommendations had completed an antimicrobial stewardship certification program and at least 1 year of residency training. Pharmacists were not scheduled to perform any clinical duties in the ED beyond positive culture reviews due to limited resource allocation. ASP pharmacists evaluated ED cultures during their daily antimicrobial stewardship activities as part of the hospital-wide ASP. This program included daily evaluation of positive cultures and broad-spectrum antibiotics, pharmacokinetic consults, renal dose adjustment, and intravenous to oral conversion of antimicrobials. The prescribed regimen was evaluated for adequacy based on discordance with culture susceptibility, current Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, relevant primary literature, and patient characteristics. Recommendations were also provided to avoid further therapy in situations where antimicrobials were unnecessary (eg, asymptomatic bacteriuria). If a prescribed regimen was found to be inadequate or the patient left the ED without an antimicrobial despite an indication for treatment, the pharmacist provided a recommendation that included a brief clinical description and 1 to 2 options for antimicrobial therapy. The pharmacists placed the formal recommendations in the electronic medical record and provided a hard copy of the recommendation with the culture and susceptibility report to the assistant ED director. The assistant ED director communicated the recommendations to the covering ED physician or mid-level provider. If therapeutic changes were made by the provider, the assistant ED director contacted the patient, called in a new prescription, if necessary, and created an addendum in the electronic medical record. In addition to the patient-specific recommendations provided by the ASP pharmacists, an informational poster was placed above the ED provider workstation highlighting guideline-based therapies for common infections.

The primary outcome was the median time to antimicrobial therapy modification in patients who were discharged with culture results and antimicrobial therapy that were inadequate. Time to therapy modification was defined as the time from finalization of culture results to the creation of an addendum in the medical record by the ED staff identifying the new antimicrobial regimen selected. Secondary outcomes were the median time from culture finalization to review; the number of appropriate empiric antimicrobial selections, antimicrobial duration, dose, and frequency per current IDSA guideline recommendations; the number of appropriate empiric antimicrobial dosing based on renal function; and 30-day ED return visit or hospital admission rates after index visit. ED provider action on inadequate prescriptions based on positive culture results was evaluated for therapeutic modification and external provider notification in pre-ASP and post-ASP implementation groups. If no action was taken by the ED provider, the chart addendum was reviewed to determine whether there was documentation that the ASP recommendation was forwarded to the patient’s primary care provider or relevant specialist. The appropriateness of final, culture-guided antimicrobial regimens was evaluated in both groups for patients where final therapy was known. Patients who had culture results or recommendations sent to an external provider were excluded in the evaluation of this endpoint.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were evaluated using χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests (age and creatinine clearance). For the primary and secondary endpoints, categorical variables were evaluated using the χ2 test and continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data. Continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs). A 2-sided P value less than .05 was used to define statistical significance.

Results

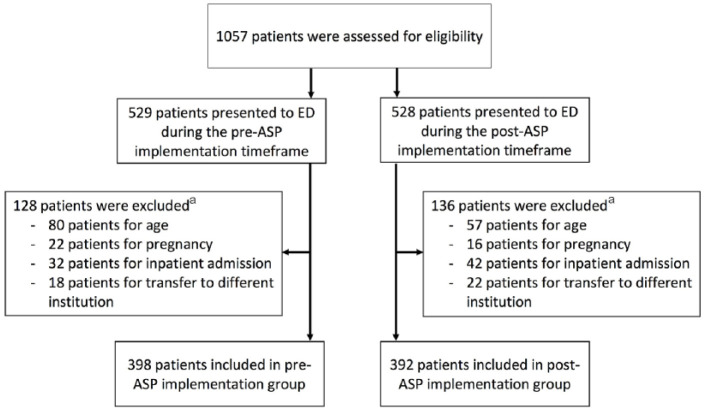

A total of 1,057 patients presented to the ED and had subsequent positive microbial cultures during the 2 study periods. In the pre-ASP group, 529 patients were managed by ED providers and 398 met the inclusion criteria. In the post-ASP implementation group, 528 patients were evaluated by the ASP pharmacists and 392 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study profile.

Note. ED = emergency department; ASP = antimicrobial stewardship program.

aPatients may have met more than 1 exclusion criteria.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups (Table 1). The majority of patients were female with a median age of 46 years without significant renal impairment. The most common positive microbial cultures were urine, followed by wound and blood. The pre-ASP group had a statistically significant higher number of positive blood cultures, and the post-ASP implementation group had a statistically higher number of wound cultures. Approximately 27% of patients with microbial culture results had inadequate empiric antibiotic therapy in both groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Pre-ASP implementation group n = 398 |

Post-ASP implementation group n = 392 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 49 (26-68) | 43 (26-68) | .435 |

| Female gender, no. (%) | 297 (74.6) | 289 (73.7) | .773 |

| Race, no. (%) | .847 | ||

| White | 302 (75.9) | 302 (77.0) | |

| Hispanic | 54 (13.6) | 46 (11.7) | |

| Black | 22 (5.53) | 25 (6.38) | |

| Other | 20 (5.03) | 19 (4.85) | |

| Known antibiotic allergy, no. (%) | 123 (30.9) | 109 (27.8) | .339 |

| Weight, median (IQR), kg | 81 (61-93) | 81 (64-91) | .757 |

| Creatinine clearance per Cockcroft-Gault, median (IQR), mL/min | 77 (49-106)a | 75 (46-102)a | .222 |

| Renal replacement therapy, no. (%) | 2 (0.50) | 2 (0.51) | .988 |

| Positive culture type | |||

| Urine, no. (%) | 287 (72.1) | 263 (67.3) | .145 |

| Wound, no. (%) | 75 (18.8) | 112 (28.3) | .002 |

| Blood, no. (%) | 26 (6.53) | 9 (2.30) | .004 |

| Miscellaneous, no. (%)b | 10 (2.51) | 8 (2.04) | .657 |

| Inadequate culture result and antimicrobial therapy, no. (%) | 113 (28.4) | 103 (26.3) | .524 |

| ED provider responded to inadequate antimicrobial therapy, no. (%) | 25 (22.1) | 86 (83.5) | <.001 |

Note. ASP = antimicrobial stewardship program; IQR = interquartile range.

For the pre-ASP implementation group, serum creatinine values only available in 213 (53.5%) patients. For the post-ASP implementation group, serum creatinine values only available in 136 (34.7%) patients.

Miscellaneous culture results included sputum, genital, stool, eye, and Clostridium difficile polymerase chain reaction results.

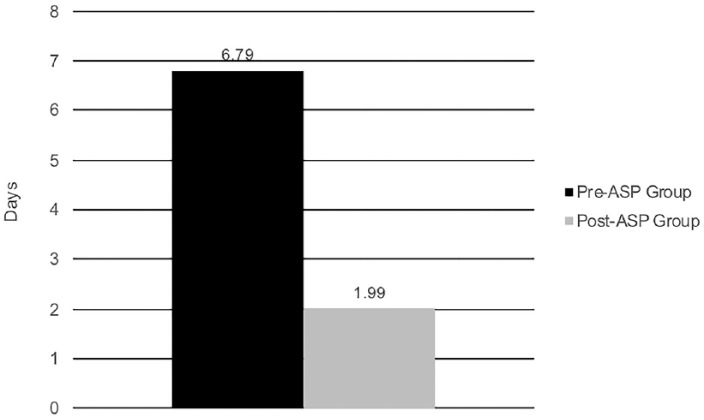

The primary endpoint of median time to modification of antibiotic therapy in patients discharged with inadequate therapy was shortened by 4.8 days in the post-ASP implementation group (P < .001, Figure 2). Median time from culture finalization to review was also significantly decreased (9.83 days [IQR 2.34-13.21] vs 0.32 days [IQR 0.076-1.12], P < .001) after implementation of the ASP-managed process.

Figure 2.

Median time from culture finalization to antibiotic therapy modification.

Note. Pre-ASP implementation (IQR 1.09-9.38 days) vs post-ASP implementation (IQR 0.34-3.41 days), P < .001. ASP = antimicrobial stewardship program; IQR = interquartile range.

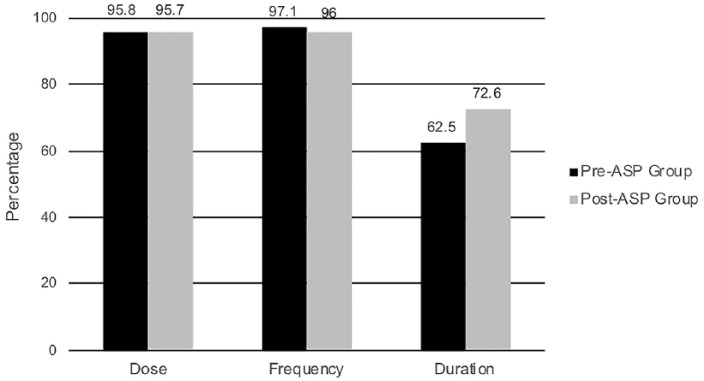

Empiric antibiotic selection adhered to IDSA guidelines in 88.9% in the pre-ASP group compared to 97.3% in the post-ASP implementation group (P < .001). The appropriateness of the empiric duration, dose, and frequency was evaluated (Figure 3). Of the patients discharged on empiric antibiotics, the post-ASP implementation patients were more likely to have a treatment duration concordant with IDSA guidelines when compared to the pre-ASP group (P = .005). The adherence of the dose and frequency to guideline recommendations was not significantly different between the 2 groups. In patients with evaluable renal function, no significant difference in appropriate antimicrobial dosing for renal function was identified between the 2 groups (P = .994). There was also no difference detected in 30-day ED return visit or hospital admission rates after index visit (36 vs 43 patients, P = .367).

Figure 3.

Empiric antibiotic adherence rates to Infectious Diseases Society of America recommended dose, frequency and duration.

Note. Results for groups represent patients who were discharged with an antibiotic. Patients who were discharged without an antibiotic and had a positive culture were excluded from this analysis. Pre-ASP implementation group (n = 312) vs post-ASP implementation group (n = 351) comparison of dose, P = .952; frequency, P = .310; and duration, P = .005. ASP = antimicrobial stewardship program.

In the post-ASP implementation period, ED providers were more likely to modify antimicrobial therapy (48.5% vs 22.1%, P <.0001) and forward results and recommendations to primary care providers (25.2% vs 8.85%, P < .0009). After excluding patients with cultures who were forwarded to external providers, the appropriateness of final, culture-guided antimicrobial agent selection improved in the post-ASP implementation period (92.6% vs 79.9%, P < .0001).

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of ED culture follow-up directed by an ASP in a facility without decentralized pharmacists in the ED. We found that ASP pharmacist involvement in the follow-up of ED cultures was associated with a decreased time to ED provider action on inadequate empiric therapy and improved overall appropriateness of final, culture-guided therapy. Additionally, ED provider adherence to guideline-recommended empiric antimicrobial selection and duration of therapy improved after the implementation of the culture follow-up program. Institutions that do not have dedicated clinical pharmacy services in the ED may be able to positively impact patient outcomes through this alternative approach to ED antimicrobial stewardship.

Facilities need effective culture follow-up programs to provide optimal and efficient care to patients discharged from the ED. Prior studies evaluating culture follow-up programs report the incidence of inadequate antimicrobial therapy to range from 10% to 50%.15,19,23 In our institution, empiric therapy was deemed adherent to guidelines in approximately 93% of patients, but 27% of patients received therapies that were inappropriate after culture sensitivity and susceptibility report finalization. Similarly, Baker and colleagues15 found that empiric agent selection was appropriate in 88% of their cohorts, but approximately 40% of cultures required further follow-up with primary care providers or patients. Even in the presence of near-optimal prescribing practices in the ED, inappropriate antimicrobial therapy still occurs, and these findings highlight the need for an effective and efficient process to manage the care of those discharged from the ED.

In addition, facilities that have culture follow-up programs managed by ED providers or nursing staff may see improvements in efficiency and accuracy if these tasks are handled by an ASP or dedicated pharmacist position in the ED. In our study, we found that involvement of an ASP pharmacist in the culture review process decreased the time to provider action on inadequate therapy and ED providers began to select more appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapies. The latter likely occurred because ASP feedback to ED providers highlighted recurring practices that were associated with inadequate antimicrobial therapy. While a standardized process of culture evaluation could improve follow-up time, the incorporation of ASP pharmacists appears to have provided additional improvement in prescribing patterns. Baker and colleagues also noted that time to follow-up and action were more rapid (2 vs 3 days, P = .0001) when conducted by a dedicated ED pharmacist.15 Similarly, Santiago and colleagues20 identified that a pharmacist-driven culture review process missed fewer patients who needed follow-up as compared to a nurse-driven process (4% vs 47%, P = .0004). While our study was not powered to detect a change in ED return visits or hospital admissions after discharge from the ED, others have seen reductions in these outcomes. Randolph and colleagues16 found a significant reduction in patient readmissions when ED pharmacists participated in the culture follow-up process (7% vs 19%, P < .001). Furthermore, Dumkow and colleagues17 found a non-significant decrease in ED revisit and hospital admission within 72 hours (16.9% vs 10.2%, P = .079); however, this was significant in a subgroup of uninsured patients (15.3% vs 2.4%, P = .044).

We acknowledge that there were a number of limitations associated with this study including the retrospective cohort study design and single center model. Due to the staffing schedule of the ASP pharmacists and the assistant ED director, culture follow-up was primarily performed during the weekdays. Although the time to ED provider action was certainly shorter in the post-ASP implementation group, further improvement may have been observed if weekend coverage was available. There was also additional time that lapsed between ASP-pharmacist review, communication with ED providers, and ultimate decision-making that prolonged time to appropriate therapy. To avoid this delay, some centers have utilized a collaborative practice agreement with ED physicians that allows ED-based pharmacists to evaluate and modify therapy as needed. In some instances, patients included in both the pre-ASP and post-ASP implementation groups had results and recommendations forwarded to primary care providers and determination of final therapy selections was unobtainable. Serum creatinine data were not available for a significant number of our patients in both groups making this secondary outcome difficult to evaluate. Last, the informational poster placed in the ED department may have also helped improve empiric prescribing patterns, although there was no significant change in the rate of inadequate therapies requiring modification after culture results were finalized.

Conclusions

This study found that incorporation of an ASP pharmacist in the ED culture review process is associated with a decreased time to ED provider action on inadequate antimicrobial therapy and improved final, culture-guided therapy. In addition, routine communication between the ASP pharmacist and the ED provider appears to improve the selection of guideline-concordant, empiric antimicrobial selection, and duration of therapy. Additional research should determine if such an intervention may reduce ED revisits or hospitalization. This model for patient care may be of interest to centers lacking an effective culture follow-up program.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Anne Dominy, RN, BSN, for her assistance with coordinating with ED providers and patients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation. Joint Commission joins White House effort to reduce antibiotic overuse. Jt Comm Perspect. 2015;35:4, 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Reform of Requirements for Long-Term Care Facilities. 42 CFR §483.80. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/04/2016-23503/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-reform-of-requirements-for-long-term-care-facilities. Updated October 24, 2016. Accessed January 24 2017.

- 3. Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation. Official publication of Joint Commission requirements: new antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jt Comm Perspect. 2016;36:1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e51-e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF, Jr, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and Infectious Diseases Society of America Joint Committee on the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals: guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:584-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Hospital Association. Trendwatch Chartbook 2016: trends affecting hospitals and health systems. http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/chartbook/2016/2016chartbook.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 27, 2017.

- 7. Rui P, Kang K, Albert M. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2013 emergency department summary tables. Date unknown. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2017

- 8. Idrees U, Clements E. The state of U.S. emergency care: a call to action for hospital pharmacists. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:2251-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roberts RR, Hota B, Ahmad I, et al. Hospital and societal costs of antimicrobial-resistant infections in a Chicago teaching hospital: implications for antibiotic stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1175-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spellberg B, Powers JH, Brass EP, Miller LG, Edwards JE., Jr. Trends in antimicrobial drug development: implications for the future. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1279-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bishop BM. Antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action for pharmacists. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29:556-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. May L, Cosgrove S, L’Archeveque M, Talan DA, Payne P, Jordan J, Rothman RE. A call to action for antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department: approaches and strategies. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:69-77.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trinh TD, Klinker KP. Antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(suppl 1):S39-S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, Fairbanks RJ, Beamish SE, Haas CE. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25:190-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, Zeina R. Effect of a pharmacist-managed culture review process in an emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:916-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dumkow LE, Kenney RM, MacDonald NC, Carreno JJ, Malhotra MK, Davis SL. Impact of a multidisciplinary culture follow-up program of antimicrobial therapy in the emergency department. Infect Dis Ther. 2014;3:45-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller K, McGraw MA, Tomsey A, Hegde GG, Shang J, O’Neill JM, Venkat A. Pharmacist addition to the post-ED visit review of discharge antimicrobial regimens. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1270-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davis LC, Covey RB, Weston JS, Hu BB, Laine GA. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5 suppl 1):S49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santiago RD, Bazan JA, Brown NV, Adkins EJ, Shirk MB. Evaluation of pharmacist impact on culture review process for patients discharged from the emergency department. Hosp Pharm. 2016;51:738-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. VanEnk J, Townsend H, Thompson J. Pharmacist-managed culture review service for patients discharged from the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:1391-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. VanDevender EA. Optimizing antimicrobial therapy through a pharmacist-managed culture review process in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1138-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ryan KO, Hughes FL. Development of a culture review follow-up program in the emergency department. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:1299. [Google Scholar]