Abstract

Introduction: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)–associated lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a concern in immunocompromised patients. Aerosolized ribavirin (RBV AER) is used for treatment of RSV LRTI; however, adverse events and rising drug costs remain a challenge for patient management. The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the efficacy and adverse event profile of RBV AER for the treatment of hospitalized RSV LRTI in immunocompromised adult patients. Methods: A Medline/PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, Clinicaltrials.gov, and Cochrane Library database search was conducted from 1966 to January 2019 for the use of RBV AER. Search strategy: [(ribavirin OR ICN1229) AND (“administration, oral” OR “oral” OR “administration, inhalation” OR “inhalation)] AND (“respiratory tract infection” OR “pneumonia”). Studies were reviewed if adult patients were hospitalized, immunocompromised, had RSV LRTI, received RBV AER, and included the outcome of mortality and/or adverse reactions. Methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration GRADE approach. Results: A total of 1787 records were identified and 15 articles met inclusion criteria: hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)/bone marrow transplant (n = 8), other malignancy/neutropenic (n = 2), solid organ transplant (n = 5). All of the trials are observational with a low quality rating; therefore, a meta-analysis was not performed. The 30-day mortality in studies that contain >10 patients with HSCT, malignancy, and transplant range from 0 to 15.4%, 6.3%, and 0 to 27%, respectively. Improved mortality was cited in 4 studies when RBV AER started before mechanical ventilation or within 2 weeks of symptom onset. Only 3 studies had comparative mortality data with RBV AER and RBV PO. Adverse reactions were reported in 5 studies and included psychiatric manifestations (anxiety, depression, feeling of isolation; n = 14), wheezing/bronchospasm (n = 6), snowflakes/hail blowing in face (n = 6), and precipitation in ventilator tubing (n = 5). Conclusion: There is a lack of high quality, comparative trials on the use of RBV AER for the treatment of RSV LRTI in adult hospitalized immunocompromised patients. There may be a mortality benefit when RBV AER is initiated early after diagnosis or prior to mechanical ventilation, but requires further study. Patient isolation and psychological effects must be weighed against the benefit of therapy.

Keywords: ribavirin, respiratory syncytial virus, lower respiratory tract infection, immunocompromised, systematic review

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and results in approximately 55 adult hospitalizations per 100 000 person years.1 In healthy adults, RSV typically manifests as an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) with patients experiencing rhinorrhea, pharyngitis, sinusitis, and cough. Treatment consists of supportive care, typically in the outpatient setting. In contrast, elderly and immunocompromised patients may progress from an URTI to a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) with symptoms ranging from dyspnea and/or chest tightness, to acute respiratory distress syndrome and respiratory failure. The availability of rapid diagnostic tests, including the multiplex polymerase chain reaction test, has increased the identification of RSV as a source of pulmonary infections.2

Treatment of RSV may be necessary in patients with impaired cellular immunity, as the ability to contain and eradicate RSV is reduced. Severely immunocompromised populations such as bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients, neutropenic patients, solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, and patients with HIV have a risk of mortality from RSV as high as 80%.3 In addition, RSV infections in lung transplant recipients may increase the risk of chronic rejection.4 Despite the high mortality and morbidity associated with RSV infections in immunocompromised patients, there remains a lack of prospective, randomized trials to help guide clinicians on appropriate management of LRTI in hospitalized adults.

Current treatment options for RSV LRTI include aerosolized or oral ribavirin (RBV) in combination with palivizumab (PZB), corticosteroids, and/or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Aerosolized ribavirin (RBV AER) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1985 for the treatment of RSV in hospitalized pediatric patients.5,6 Therapy may only be administered via the small particle aerosol generator, which produces particles in the range of 1.0 to 1.3 µm to ensure adequate concentrations in the lower respiratory tract.7 Safety concerns of RBV AER include bronchospasm and dyspnea; furthermore, health care workers and visitors must be aware of potential teratogenic effects. In addition, cost of RBV AER has risen dramatically since FDA approval, with most recent estimates of an average wholesale price (AWP) of nearly US $120 000 for four 6 g vials and US $10 000 less for the generic.8

Drug administration barriers, including high acquisition cost, and lack of controlled trials have made use of RBV AER for treatment of RSV LRTI in hospitalized adults with immunocompromising conditions challenging.9 The decision to initiate therapy is even more difficult when immunocompromised patients present with RSV LRTI to a nontransplant community hospital, which might not have established protocols like transplant or oncology centers. The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the efficacy and adverse drug event (ADE) profile of RBV AER for the treatment of RSV LRTI in adult immunocompromised patients.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This systematic review was designed to examine the outcomes reported in comparative clinical trials and cohorts for the use of RBV AER in the treatment of LRTI caused by RSV in hospitalized immunocompromised adults. A systematic search of the literature was conducted in the following databases: Medline via PubMed (1966-May 2016) date of last search January 8, 2019; Embase (<1966-May 2016); Clinicaltrials.gov; The Cochrane Library (no date limit); and Google Scholar (no date limit) Search terms included “ribavirin,” “ICN 1229,” “administration, inhaled” or “inhalation,” “administration, oral” or “oral,” “respiratory syncytial virus,” “drug therapy,” “pneumonia,” “respiratory tract infection,” “respiratory syncytial virus infections/drug therapy.” Example search strategy for Pubmed: Search strategy: [(ribavirin OR ICN 1229) AND (“administration, oral” OR “oral” OR “administration, inhalation” OR “inhalation”)] AND (“respiratory tract infection” OR “pneumonia”). Additional references were identified from records in the original search, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines, and the FDA database Drugs@FDA.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were based upon the PICOS method, and records meeting all of the following criteria were included in the qualitative analysis.10 Patient population was defined as immunocompromised hospitalized adults ≥18 years old with HSCT or BMT, other malignancy, neutropenia, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≤500 neutrophils/mL, SOT, HIV, chronic corticosteroid use defined as greater than 10 mg of prednisone or equivalent per day,11 or receipt of maintenance immunosuppressant(s). Patients must also have a documented RSV infection of the lower respiratory tract or RSV pneumonia. Intervention criteria included treatment with RBV AER alone or in combination with other therapies. Studies were included whether or not comparison with oral or intravenous RBV or other drug therapies occurred. To meet inclusion criteria, studies must have reported at least one of the following outcome measures: in-hospital mortality, 30-day all-cause mortality, or RSV mortality defined by autopsy, or change in pulmonary function as defined in the article. If specific mortality was not stated, it was assumed to be in-hospital mortality. Post hoc, the decision was made to include the occurrence of obstructive bronchiolitis (OB) or bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) as an outcome in lung transplant recipients. All observational studies and controlled trials, retrospective or prospective, meeting all or any of the above criteria were included. Reviews and foreign language publications were excluded. When outcomes were inseparable for mixed populations, the study was excluded. For example, studies reporting adult and pediatric population outcomes were excluded if the adult outcomes were not reported separately. Other examples of mixed populations are mixed community-acquired respiratory viruses (ie, parainfluenza virus), mixed upper and LRTI, and mixed RBV methods of administration.

Study Selection and Quality Assessment

Search results were divided and reviewed independently by L.A. or C.H. and all records were reviewed by K.M.W. The authors first reviewed titles and abstracts. Records not immediately rejected were obtained in full text and reviewed for inclusion criteria by L.A. or C.H. A second determination of inclusion versus exclusion was performed by K.M.W. Adjudication was performed by the third author when necessary. The only exception to this process was the handling of the Google Scholar search results. Due to the high volume of citations returned, K.M.W. performed the initial determination independently and then L.A. or C.H. performed the second determination. Selected studies were reviewed for quality based upon the GRADE approach.12 Randomized clinical trials may begin with a high quality rating and observational studies begin with a low quality rating. Quality levels are upgraded or downgraded based upon several factors such as, but not limited to, design, precision, or bias. Some trials may be down or upgraded for multiple factors.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction was performed independently by C.H. (HSCT) and L.A. (all other populations) and verified by K.M.W. All relevant PICOS data, sample size, study time period, limitations, RBV dose and frequency, duration of therapy, monotherapy versus combination therapy, timing of treatment (early vs late), and mechanical ventilation (MV) were collected. Discrepancies or disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors.

Search Results

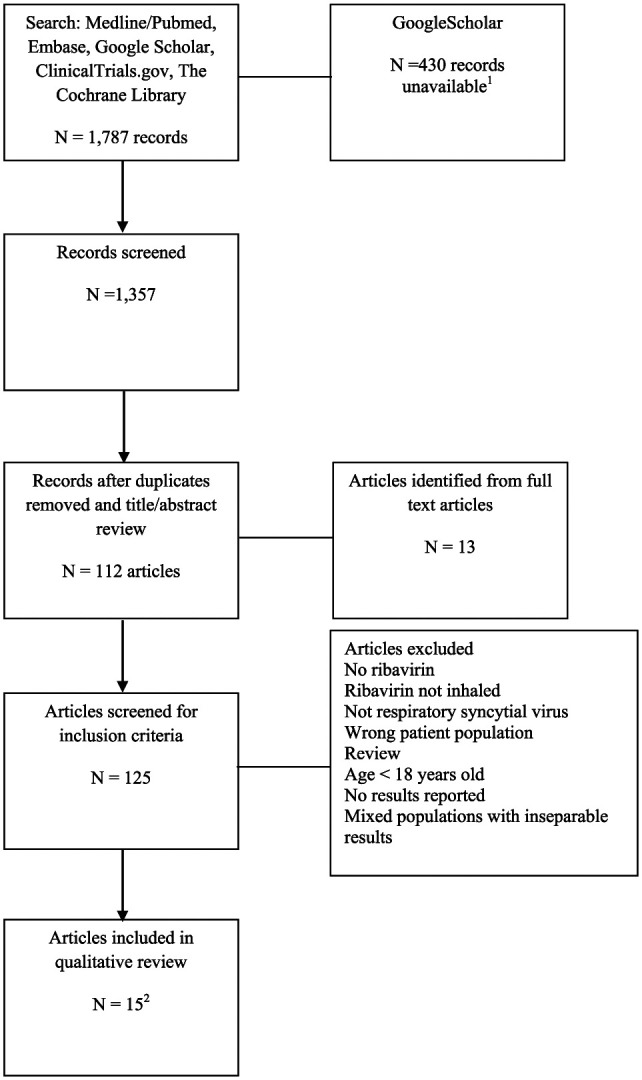

A total of 1787 records were identified. The Google Scholar search comprised 75% of the records (1350). The PRISMA flow diagram is located in Figure 1.10 This qualitative review includes 15 publications meeting inclusion criteria; 13 identified in the original systematic search and 2 identified via the updated PubMed search.13-27 All of the trials are observational and begin with a low quality rating. No trials meet criteria for upgrading to moderate or high quality, including the 3 prospective trials.14,22,25 No articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria for patients with HIV, receiving chronic corticosteroids, or maintenance immunosuppressant therapies. Based on the lack of randomized trials, lack of comparative groups, and heterogeneity of the study population, a narrative review was prepared.

Figure 1.

Selection of records for systematic review.

1The Google Scholar search returned 1350 records. Multiple attempts to advance beyond the 920th record failed with the response “Server Error.”

2There were 13 trials meeting inclusion criteria in the primary search. The Pubmed search was repeated on January 8, 2019, and 2 additional trials met inclusion criteria.

Oncology HSCT/BMT Patients

A total of 163 cases of RSV LRTI were reported in 8 articles (Table 1),13-20 published from 1995-2018, on the use of RBV AER in oncology patients focusing on BMT/HSCT recipients. All articles were classified as low or very low quality data. Numbers of patients who underwent allogeneic and autologous BMT or HSCT are listed when available. Of the 163 cases, 125 received RBV AER, 3 received IVIG monotherapy, and 32 received RBV PO. The most common reported dosage regimen included 2 g inhaled over 2 to 3 hours every 8 hours (n = 58), or 6 g inhaled over 18 hours every 24 hours (n = 23). Duration of RBV AER therapy ranged from 1 to 30 days. A total of 85 patients received RBV AER in combination with adjunctive therapy such as IVIG, IVIG (RSV-neutralizing antibodies), and /or PZB.13-19 Early versus late treatment outcomes with MV was reported in 2 trials.13,14 Only one study had comparative mortality data with RBV PO.20

Table 1.

RBV AER in Hospitalized Adult Oncology Patients (Focus on HSCT/BMT Recipients With RSV LRTI).

| References | Type of study year | No. of patients with LRTI | Agent(s) Duration of therapy |

Time from diagnosis to start of RBV | Outcome(s) | ADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghosh et al13 | Retrospective cohort 1992-2000 |

6 breast cancer patients PBSC = 2 BMT = 4 |

RBV AER 6 g over 18 h every 24 h + IVIG 500 mg/kg every 48 h (n = 5) RBV AER 6 g over 18 h every 24 h + IVIG (RSV-neutralizing antibodies) 500 mg/kg every 48 h (n = 1) Duration of therapy: mean: 12 d (7-17 d) |

Early treatment: initiated <24 h before MV Late treatment: initiated ≥24 h after MV |

■ In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 33% (2/6) ■ 30-d mortality RBV AER: 17% (1/6) ■ Early vs late treatment outcomes ◦ Mortality in patients receiving early treatment: 20% (1/5) ◦ Mortality in patients receiving late treatment: 100% (1/1) ■ Outcome based on days after BMT: ◦ Pre-engraftment: 40% (2/5) ◦ Post-engraftment: 0% (0/1) |

NR |

| Whimbey et al14 | Prospective surveillance study (cohort) January 8 to March 3, 1993 |

19 BMT | RBV AER 6 g over 18 h every 24 h + IVIG (RSV-neutralizing antibodies) 500 mg/kg every 48 h (n = 16) Duration of therapy: mean: 11 d (3-22 d) |

Early treatment: initiated >1 d before intubation Late treatment: initiated within 1 d of intubation |

■ In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 56% (9/16) ■ Early vs late treatment outcomes ◦ Mortality in patients receiving early treatment: 22% (2/9) ◦ Mortality in patients receiving late treatment: 100% (7/7) ◦ Early initiation was associated with survival (P < .05) |

Anxiety, depression, isolation, and/or loneliness (n = 12) Psychiatric consultation (n = 3) Noncompliance (n = 3) Snowflakes and hail blowing in the face (n = 4) Psychiatric consultation (n = 3) Crystallization in ventilation tubing but no airway obstruction (n = NR) |

| McCoy et al15 | Retrospective cohort 2006-2008 |

13 HSCT/lymphoma/leukemia | RBV AER 6 g over 12 h every 24 h × 3 d + PZB 15 mg/kg IV over 1 h × 1 (n = 13) Duration of therapy: mean number of RBV AER doses: 5 ± 2.1 |

Given as soon as possible | ■ 30-d mortality RBV AER: 0% (0/13) | NR |

| Bourgouin et al16 | Retrospective cohort 2000-2012 |

16 allo | RBV AER 2 g every 8 h × 15 doses + IVIG 500 mg/kg/d × 4 d (n = 16) Duration of therapy: 5 d |

NR | ■ In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 6.3% (1/16) | NR |

| Mihelic et al17 | Retrospective cohort 2007-2013 |

31 BMT/leukemia | RBV AER (unknown dose) plus PZB (unknown dose) (n = 31) | NR | ■ RSV mortality RBV AER: 6.5% (2/31) | NR |

| McCarthy et al18 | Retrospective cohort 1993-1998 |

4 allo BMT | RBV AER 6 g over 18 h every 24 h + RBV IV 15 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses + IVIG (n = 1) IVIG 0.2-0.4 g/kg/d 2 or 3 times weekly (n = 3) Duration of therapy: median 17 d (8-30 d) |

Within 24 h (0-16 d) |

■ In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 0% (0/1) ■ In-hospital mortality IVIG: 100% (3/3) |

NR |

| Peck et al19 | Retrospective cohort 1987-2000 |

2 allo | RBV AER 2 g over 2 h every 8 h + IVIG (n = 1, survivor) RBV AER 2 g daily × 4 d then 2 g over 2 h every 8 h; received IVIG throughout RBV AER therapy (n = 1, nonsurvivor) Duration: unknown |

NR | ■ In-hospital/30-d mortality RBV AER: 50% (1/2) ■ Both cases infected during conditioning period |

NR |

| Foolad et al20 | Retrospective cohort 2014-2017 |

72 BMT | RBV AER 2 g over 3 h every 8 h (n = 40) RBV PO 600 mg every 8 h or 10 mg/kg followed by 20 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses (n = 32) Duration of therapy: NR |

NR | ■ 30-d mortality RBV AER: 15.4% (6/39) ■ 30-d mortality RBV PO: 13.8% (4/29) P = 1.0 ■ 90-d mortality RBV AER: 30.8% (12/39) ■ 90-d mortality RBV PO: 17.2% (5/29) P = 0.263 |

NR for LRTI population |

Note. RBV = ribavirin; AER = aerosolized; HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplant; BMT = bone marrow transplant; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; LRTI = lower respiratory tract infection; ADE = adverse drug event; PBSC = peripheral blood stem cell; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin; MV = mechanical ventilation; NR = not reported; PZB = palivizumab; IV = intravenous; allo = allogeneic; auto = autologous.

Ghosh et al13 studied cases of RSV infections in autologous BMT/peripheral blood stem cell breast cancer patients over an 8-year period from 1992 to 2000. Of a population of 249 patients, only 6 developed RSV LRTI. Disease onset occurred less than 30 days from transplant in 5 patients and between 30 and 100 days in one patient. A total of 5 of the 6 patients were in the pre-engraftment period with all 6 patients having lymphocyte counts of ≤200 cells/mL. Engraftment was defined as the absence of neutropenia for 3 days after conditioning therapy and transplantation. Patients were treated with a combination of RBV AER and IVIG or RSV-IVIG for a mean of 12 days. Length of therapy was based on the patients’ immunologic status, response, and duration of viral shedding. In-hospital mortality was 33% (2/6), with both patients who expired being in the pre-engraftment period. Initiation of combination therapy occurred during the upper respiratory stage for one patient who progressed to pneumonia and survived. The remaining 5 patients had therapy initiated at the pneumonia stage with 2 deaths. Mortality in patients receiving RBV AER within 24 hours of MV was 25% (1/4) compared with 100% (1/1) who received therapy post MV.

Whimbey et al14 prospectively reviewed adult BMT patients hospitalized with RSV pneumonia or tracheobronchitis over a 9-week period. Pneumonia was diagnosed in 16 patients, with 4 patients progressing to pneumonia from tracheobronchitis. Of the 16 patients, 6 patients were in the pre-engraftment period and 4 were neutropenic. A total of 16 patients received combination therapy with RBV AER and IVIG with RSV-neutralizing antibodies. Duration of therapy was determined by severity of illness, clinical response, and engraftment status. Overall in-hospital mortality was 50% (8/16). Early treatment, defined as RBV AER given greater than 1 day before MV, resulted in a mortality of 33% (4/12) compared with 100% (4/4) who received treatment within 1 day of intubation. All 4 patients who did not receive RBV AER expired. When stratified by type of transplant (autologous vs allogeneic), neutropenia (<1000 neutrophils/mL), and engraftment status (resolution of neutropenia after transplant), the author stated that mortality was not significantly influenced by these risk factors, although the number of patients in this study is small.

McCoy et al15 retrospectively reviewed adult patients with hematologic malignancies or HSCT who were diagnosed with RSV infections and received RBV AER with or without PZB treatment from 2006 to 2008. A guideline developed by their interdisciplinary antibiotic stewardship team recommended RSV LRTI patients receive RBV AER for 3 days and one dose of PZB as soon as possible from diagnosis, then reassess for continued RBV AER every 3 days. Of the 26 patients with RSV infection, 13 were diagnosed with LRTI. Severe immunodeficiency was present in 7 of the 13 patients with LRTI. This was defined as HSCT ≤6 months from RSV diagnosis, leukopenia (white blood count ≤2 cells × 103/mm3), or lymphopenia (lymphocytes ≤0.1 cells × 103/mm3). The 30-day mortality was 0% (0/13) in this population.

Bourgouin et al16 retrospectively studied allogeneic transplant patients diagnosed with RSV from January 2000 to June 2012. Patients with neutropenia, pneumonia, or active graft versus host disease received treatment with a standardized protocol of RBV AER for 5 days and IVIG for 4 days. The authors presented the results of the first 32 patients in abstract form. Donor characteristics included 15 matched sibling, 13 matched unrelated, and 4 mismatched donors. The median (interquartile range) day from transplant to RSV infection was 382 (241-1049). Only 1 death occurred in 16 patients diagnosed with a LRTI, with a reported case fatality rate of 6.3% (95% confidence interval = 0.2%-30.2%).

Mihelic et al17 performed a retrospective cohort study of BMT and leukemic patients from 2007 to 2013 infected with RSV who presented to a hospital with either an URTI or a LRTI.17 A total of 60 patients were hospitalized and 31 diagnosed with LRTI. The median (range) of ANC and acute lymphocyte count for all infected patients was 1.6 (0-11) cells/mm3 and 0.8 (0-7.3) cells/mL, respectively. Patients treated with RBV AER and PZB had a 60-day mortality of 12.9% (4/31) and a RSV mortality rate of 6.5%. The authors mentioned that therapy was started early, but there was no details provided in the abstract.

McCarthy et al18 retrospectively reviewed all patients with an allogenic BMT and RSV disease over a 5-year period from 1993 to 1998. Patients were identified for review by virology reports, search of the BMT database, and anecdotal reports. Of the 26 patients identified, only 4 were adult patients with LRTI. A LRTI infection in this study was defined as positive chest signs and/or significant hypoxemia with oxygenation saturation of less than 90% on room air. Only 1 of the 4 patients had a positive infiltrate on chest radiograph. Of the 4 patients, 1 patient received RBV AER in combination with RBV IV and IVIG and survived. The remaining 3 patients received IVIG monotherapy with 100% mortality, although none reported as RSV related.

Peck et al19 performed an observational study that included all HSCT candidates who had positive RSV surveillance testing prior to BMT. There were 37 pediatric and adult patients who were diagnosed with RSV URTI prior to transplant. Of these patients, 3 adults were diagnosed after the start of cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation conditioning regimen and were transplanted. Respiratory syncytial virus progressed to LRTI in 2 patients and both received RBV AER combination therapy. One patient died of RSV pneumonia and the other survived the RSV infection, but died on day 90.

Foolad et al20 performed a retrospective cohort study on all HSCT patients with either an URTI or a LRTI who received greater than 48 hours of RBV AER or RBV PO from September 2014 to April 2017. Of 124 patients identified, 72 patients received RBV at the LRTI stage. A total of 40 received RBV AER and 32 received RBV PO. Demographic data were not stratified by patients with LRTIs. The dosing regimen of RBV AER was 2 g over 3 hours every 8 hours or RBV PO dosed at 600 mg every 8 hours or 10 mg/kg followed by 20 mg/kg/d divided into 3 doses. There were no criteria reported for determination of RBV duration of therapy. The duration of therapy for URTI and LRTI combined is a median (interquartile range) of 5 (4-5) and 5 (5-8) for RBV AER and RBV PO, respectively; separate data were not reported. In addition, patients did not receive concomitant immunoglobulin therapy. There was no difference in 30-day mortality in patients treated with RBV PO and RBV AER—4/29 (13.8%) and 6/39 (15.4%), respectively, P = 1.0. The authors did not comment on the 4 patients who were not included in the mortality analysis. Length of stay, transfer to the intensive care unit, and MV was reported for both URTI and LRTI population, but was not stratified to the LRTI population.

Other Malignancy or Neutropenic Patients (ANC ≤ 500 neutrophils/mL)

A total 33 cases of RSV LRTI occurring in oncology/neutropenic patients who received RBV AER were reported in 2 articles (Table 2) published in 1995 and 2014.21,22 The articles were classified as low or very low quality. All participants had a diagnosis of leukemia and did not undergo a BMT/HSCT. Of the 33 cases, 22 received RBV AER and 11 were not treated. Aerosolized ribavirin dosing regimens varied from 2 g over 2 to 3 hours every 8 hours to 6 g aerosolized over 18 hours daily. Duration of RBV AER therapy ranged from 2 to 36 days. Combination therapy with IVIG was documented in 6 patients, and 16 patients received either monotherapy or combination therapy with IVIG or PZB. One article addressed early versus late treatment outcomes in MV patients.22

Table 2.

RBV AER in Hospitalized Adult Other Malignancy or Neutropenic Patients (ANC ≤500 neutrophils/mL) With RSV LRTI.

| References | Type of study | Number of participants with LRTI | Agent(s) Duration of therapy |

Time from diagnosis to start of RBV | Outcome(s) | ADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres et al21 | Retrospective cohort 2000-2005 |

27 AML/ALL ANC <500 neutrophil/mL Lymphopenia <1000 lymphocytes/mL |

RBV AER 6 g (20 mg/mL) for 18 h every 24 h or 2 g (60 mg/L) over 2 to 3 h every 8 h ± IVIG 500 mg/kg q48h for duration of RBV therapy ± PZB 15 mg/kg × 1 (n = 16) Median duration: 7 d (2-14 d) No treatment (n = 11) |

Median = 1 d (1-12 d) | • 30-d mortality RBV AER: 6.3% (1/16) • 30-d mortality no treatment: 36% (4/11) • P = .1 |

NR |

| Whimbey et al22 | Prospective cohort 1993-1994 |

6 AML, ALL, CML ANC <500 neutrophils/mL Lymphopenia <200 lymphocytes/mL |

RBV AER 20 mg/mL 18 h by face mask or endotracheal tube + IVIG 500 mg/kg q48h for duration of RBV AER treatment (mean = 19 d, range = 9-36 d) LOT individualized based on severity, clinical response, and time to recovery from neutropenia |

NR Late therapy: within 24 h of MV |

• In-hospital mortality RBV AER combination therapy: 83% (5/6) • RSV mortality RBV AER: 67% (2/3) • MV mortality RBV AER late therapy: 100% (4/4) • 1 patient who died was noncompliant with treatment 50% of the time • 1 survivor had low oxygen requirement when treatment was started, FIO2 = 35% |

Precipitation of RBV therapy in respiratory tubing (n = 4) Nonintubated patients complaining of snowflakes and hail blowing in face (n = 2) Anxiety (NR) Loneliness due to confinement from treatment (NR) Psychologically unable to tolerate (n = 1) Wheezing (n = 4) Responded to bronchodilators and patients also had wheezing before therapy |

Note. RBV = ribavirin; AER = aerosolized; ANC = absolute neutrophil count; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; LRTI = lower respiratory tract infection; ADE = adverse drug event; AML = acute myeloid leukemia; ALL = acute lymphoblastic leukemia; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin; q48h = once every 48 hours; PZB = palivizumab; NR = not reported; CML = chronic myelogenous leukemia; LOT = length of therapy; MV = mechanical ventilation; FIO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen.

Torres et al21 performed a retrospective cohort study of leukemic patients with evidence of RSV identified by the microbiology laboratory. Of 52 patients identified, 45 were admitted to the hospital and 27 patients were diagnosed with a LRTI. Of those with a LRTI, 26% were admitted to the ICU, the median Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score was 16 (9-23), and the median length of hospital stay was 12 days. A total of 16 patients received RBV AER either as monotherapy or in combination with IVIG or PZB. Aerosolized ribavirin was initiated a median of 1 day (1-12) from RSV diagnosis. The 30-day mortality rate was 6.3% (1/16) compared with 36% (4/11) in the no treatment group (P = .1).

Whimbey et al22 performed a prospective cohort study to determine outcomes of all adult leukemia patients who were hospitalized with an acute respiratory illness and RSV was identified by culture. A total of 6 patients presented with LRTI, neutropenia, and lymphopenia and received treatment with RBV AER in combination with IVIG. The duration of therapy was individualized at the discretion of the prescriber, based on illness severity, clinical response, and time to recovery from neutropenia. In-hospital mortality was 83% (5/6). All 4 patients who were initiated on RBV AER within 24 hours of MV died. The sole survivor received early treatment when the FIO2 was 35% with a low supplemental oxygen requirement.

SOT Recipients

A total 65 cases of RSV LRTI were reported in 4 articles (Table 3),23-26 published from 1998-2012 in adult SOT patients. One study included 36 immunocompromised patients with approximately 50% lung transplant patients.27 All studies were classified as low or very low quality. The work by Zamora et al25 was designed with case match comparators that may increase its quality rating, but as it was published only as an abstract, a full quality analysis could not be completed. The majority of patients were lung or heart-lung recipients. Of the 101 cases, 76 were initiated on RBV AER and 23 on RBV PO. A single patient received RBV AER with transition to RBV PO and 2 were not treated. Aerosolized ribavirin dosing regimens varied from 2 g every 8 hours to 6 g over 12 or 18 hours daily. Duration of RBV AER therapy ranged from 3 to 30 days. Early versus late treatment outcome was addressed in one study,25 and 2 studies reported outcomes with MV.23,24 BOS/OB was addressed in 3 studies.24-26

Table 3.

RBV AER in Hospitalized Adult Solid Organ Transplant Recipients With RSV LRTI.

| References | Type of study | Number of participants with LRTI | Agent(s) Duration of therapy |

Time from diagnosis to start of RBV | Outcome(s) | ADEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ariza-Heredia et al23 | Retrospective cohort 2007-2009 |

8 Lung: 2 Kidney: 2 Kidney/pancreas: 1 Liver: 3 |

RBV AER 6 g over 18 h × 30 d (n = 1) RBV AER 6 g over 18 h × 10 d, PZB (n = 2) RBV AER 6 g over 18 h + PZB, IVIG × unknown duration (n = 1) RBV AER 6 g over 18 h × 7 d, RBV 400 mg PO every 8 h × 4 d (n = 1) RBV PO × 5 d (n = 1) RBV PO, PZB, IVIG × 5 d (n = 1) (RBV PO dose ranged from 300 mg every 12 h to 600 mg every 8 h) No therapy (n = 1) |

4.1 d (range = 2-5 d) | • In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 0% (0/5) • In-hospital mortality RBV PO: 50% (1/2) • In-hospital mortality no treatment: 0% (0/1) • In-hospital mortality RBV AER combination therapy: 0% (0/4) • In-hospital mortality RBV AER monotherapy: 0% (0/1) • MV mortality RBV PO: 50% (1/2) • MV mortality no treatment: 0% (0/1) Outcome based on days after transplant: • ≤365 d: mortality: 1/5 • 365 d: mortality: 0/3 Organ rejection: 0% (0/8) Length of stay RBV AER: 11 to 30 d |

AER: no adverse events encountered PO: hemolytic anemia (n = 1) (occurred in patient who initially received RBV AER) required transfusion |

| Palmer et al24 | Retrospective cohort 1992-1997 |

5 Single lung: 4 Bilateral lung transplant: 1 |

RBV AER (n = 4) No treatment (n = 1) |

NR | • In-hospital mortality RBV AER: 25% (1/4) • MV mortality RBV AER:50% (1/2) Outcome based on days post-transplant: • ≤365 d RBV AER: mortality: 50% (1/2) • 365 d: RBV AER mortality: (0/2) OB–RBV AER: 50% (2/4) mean follow-up 758 d |

NR |

| Zamora et al25 | Prospective case control 2004 |

44 Lung transplant |

Group A RBV AER 2 g TID × 5 d + MP 10 mg/kg/d × 3 d, + RSV IVIG 500 mg/kg × 1 dose OR PZB 15 mg/kg × 1 dose + IVIG 500 mg/kg × 1 dose (n = 33) Group B RBV AER 2 g TID × 5 d + MP 10 mg/kg/d × 3 d or group A therapy started > 2 wk after symptom onset (n = 11) Group C Controls (not infected with RSV) (case matched for indication for lung transplant and time from lung transplant) (n = 33) |

NR | Group A • 30-d mortality: 0% (0/33) • BOS: 21% (7/33) onset: 11.1 ± 8 mo Group B • 30-d mortality: 27% (3/11) • BOS: 100% (8/8), P < .05, onset: 6.8 ± 4 mo Group C • 30-d mortality: 0% (0/33) • BOS: 15% (5/33), onset: 14.1 ± 6 mo |

NR |

| Li et al26 | Retrospective cohort 2006-2010 |

8 Lung or heart/lung transplant |

RBV AER 6 g over 12 h × 3-5 d ± IVIG, MP (10-15 mg/kg/d) (n = 8) RBV 400 mg PO TID × 5-10 d ± IVIG, MP (10-15 mg/kg/d) (n = 4) |

NR | • In-hospital/30-d mortality RBV AER: 0% (0/8) • In-hospital/30-d mortality RBV PO: 0% (0/4) • Length of stay (included URTI and ambulatory patients) ■ RBV AER: 5 ± 1.5 d ■ RBV PO: 11 ± 15.1 d • BOS (included URTI and ambulatory patients) ■ RBV AER: 3 patients baseline BOS 1 or greater at time of infection, 2 patients had new onset or progression of BOS at 6 mo ■ RBV PO: no BOS reported |

AER: no adverse events encountered PO: anemia within 2 wk (1) |

| Trang et al27 | Retrospective cohort 2013-2016 |

19 Lung transplant 50% of population of RBV AER 17 Lung transplant 45% of population of RBV PO |

RBV AER 6 g over 6 h qd RBV PO 800 mg PO BID if weight ≥75 kg or 600 mg PO BID if weight <75 kg Hematologic malignancy and HSCT patients IVIG 500 mg/kg IV 3 times weekly × 2 wk was given at the discretion of treating physician |

NR | • 30-d mortality RBV AER: 5.3% (1/19) • 30-d mortality RBV PO: 17.6% (3/17) • No patients required MV |

Nausea (n = 6) (not reported if RBV PO or RBV AER) Bronchospasm (n = 2) (RBV AER) Thrombocytopenia/ decrease absolute lymphocyte count (n = 1) RBV PO |

Note. RBV = ribavirin; AER = aerosolized; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus; LRTI = lower respiratory tract infection; ADE = adverse drug event; PO = oral; PZB = palivizumab; IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin; MV = mechanical ventilation; NR = not reported; OB = obstructive bronchiolitis; TID = 3 times a day; BOS = bronchial obliterans syndrome; MP = methylprednisolone; URTI = upper respiratory tract infection; qd = every day; BID = twice a day; HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplant; RSV IVIG = IVIG with RSV-neutralizing antibodies.

Ariza et al23 performed a retrospective cohort study of adult and pediatric SOT patients hospitalized with RSV during 2007 to 2009. Of 263 cases, only 8 adult patients with RSV LRTI were identified. Transplants included lung (n = 2), kidney (n = 2), kidney/pancreas (n = 1), and liver (n = 3). Lymphocyte counts were ≤500 cells/mm3 in 6 of the 8 patients. The time from RSV diagnosis to the initiation of either RBV AER or RBV PO was 4.1 (range = 2-5) days. In-hospital mortality occurred in 0 of 5 and 1 of 2 patients treated with RBV AER and RBV PO, respectively. One death occurred in a patient infected with RSV 21 days post lung transplant and was on MV for 212 days. The hospital length of stay ranged from 11 to 30 days and 22 to 212 days in patients who received RBV AER and RBV PO. The author also reported that RBV AER started after 4.5 days compared with 2.5 days from diagnosis resulted in a trend of increased hospital length of stay and prolonged viral shedding.

Palmer et al24 retrospectively evaluated lung transplant patients with community-acquired viral infections including adenovirus, RSV, influenza, or parainfluenza viruses from 1992 to 1997 and compared outcomes to patients without viral infections. Of 10 patients with viral infections, 5 patients were infected with RSV. All patients were within 24 months post-transplant. Of the 5 patients, 4 patients received RBV AER with 1 death reported during hospitalization. Mechanical ventilation was required in 2 patients with 1 of the 2 patients surviving. There were no data on the timing of RBV AER in respect to MV. In addition, 2 of the 4 surviving patients developed OB. The diagnosis of OB was made pathologically or clinically if there was a decline in spirometry >15% of baseline without evidence of acute rejection or infection.

Zamora et al25 in a prospective case control study evaluated 30-day mortality and incidence of BOS in 44 lung transplant patients receiving RBV AER monotherapy or combination with PZB, RSV IVIG, or IVIG. This study found a statistically significant lower 30-day mortality (0% vs 27%) and incidence of BOS (21% vs 100%) in the early treatment group, defined as less than 2 weeks post symptom onset. This was in abstract form, and the patients treated more than 2 weeks post symptom onset were not clearly delineated.

Li et al26 performed a retrospective cohort of adult lung or heart/lung transplant patients from 2006 to 2010 with the primary outcome to compare the use of RBV AER and RBV PO on the incidence of BOS progression in RSV-infected patients. Included patients had to be at least 30 days from transplant and were excluded if survival was less than 6 months. Treatment was determined by prescriber preference. A total of 19 patients were included in the analysis; 12 patients with LRTI were treated with RBV AER (4 patients) or RBV PO (8 patients). Only 4 of the 8 patients treated with RBV PO were hospitalized. Severe disease, defined as the need for MV, was present in 1 and 2 patients in the RBV AER and RBV PO groups, respectively. Hospital and 30-day mortality was 0% (0/8). Hospital length of stay (including URTI) with RBV AER and RBV PO was 11 ± 15.1 and 5 ± 1.5 days, respectively (P = .37). The primary outcome of BOS included both patients with URTI and LRTI. Infection severity was defined by oxygen requirement and was similar in both groups. A total of 3 of the 15 patients who received RBV AER at baseline had BOS 1 or greater at the time of infection and 2 patients progressed or developed new-onset BOS at 6 months follow-up. There were no cases of BOS in the 6 patients who received RBV PO.

Trang et al27 performed a retrospective cohort study from 2013 to 2016 on adult patients who received either RBV AER or RBV PO for the treatment of RSV infections in the outpatient or inpatient setting. Of 240 patients with RSV disease, only 36 patients had LRTI and were hospitalized. This cohort consisted of patients with HCT, hematologic malignancy (nontransplant), lung/liver transplant, and structural lung disease. A total of 19 and 17 patients were treated with RBV AER and RBV PO, respectively. There were no criteria for the duration of therapy. The median RBV duration for all patients (URTI and LRTI) was 9 days in the RBV AER group and 10 days in the RBV PO group. Patients in the HCT group may have also received concomitant treatment with IVIG. All-cause 30-day mortality in the LRTI cohort was 1 (5.3%) of 19 and 3 (17.6%) of 17 in the RSV AER and RSV PO group, respectively. There were 5 and 2 patients in the RBV AER group and RBV PO group, respectively, who required an increase in supplemental oxygen. None of the patients in either group required MV.

Adverse Drug Events

Documentation of ADEs was available in 5 of the 15 studies reviewed.14,22,23,26,27 ADEs related to RBV AER included psychiatric manifestations (anxiety, depression, feeling of isolation; n = 14), wheezing (n = 4), bronchospasm (n = 2), snowflakes/hail blowing in face (n = 6), and precipitation in ventilator tubing (n = 5). There were 2 patients who developed anemia after receiving RBV PO, one requiring a blood transfusion. One patient on RBV PO developed thrombocytopenia and a decrease in absolute lymphocyte count. Nausea was reported in 6 patients, but did not state whether the patients were on RBV AER or RBV PO.

Discussion

This systematic review was designed to review the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and ADEs to help practitioners decide whether to initiate RBV AER for treatment of RSV LRTI in hospitalized adult immunocompromised patients. An extensive literature search revealed an absence of randomized clinical trials to provide quality evidence. The reviewed trials span from 1987 to 2017 and use different dosing regimens, durations, timing from diagnosis, and diagnostic methods to detect RSV disease. It was also difficult to discern population data on patients with LRTI, as a majority of studies included data on both URTI and LRTI. In this systematic review, 4 trials present mortality as a function of timing of RBV AER therapy and the authors report a mortality benefit.13,14,22,25 The efficacy of this treatment modality appears to be decreased if the therapy is initiated after the start of MV. This may be related to problems with administration of RBV AER in patients on MV or severity of illness. Patient isolation and the resulting psychological effects must be weighed against the benefit of therapy.

Currently, there are no published systematic reviews that evaluate the use of RBV AER for LRTI in the adult immunocompromised population. A recent 2-year observational study reported a 30-day mortality rate in HSCT/SOT, immunocompromised nontransplant patients, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients of 5.8%, 4.2%, and 10.3%, respectively.28 This study did not differentiate between URTI, LRTI, and RBV route of administration. Shah and Chemaly29 published a review in HSCT patients with LRTI and reported a RSV mortality of 24% in patients receiving RBV AER combination therapy. The definition of RSV mortality was not based on autopsy results. It is difficult to compare mortality among the studies reviewed as most studies contained less than 10 patients with LRTI treated with RBV AER. The 30-day mortality in studies that contain more than 10 patients with HSCT, malignancy, and transplant range from 0% to 15.4%, 6.3%, and 0% to 27%, respectively.15-17,20,21,25,27

The paucity of comparative data was evident in this review. Of the observational studies reviewed, only 3 studies compared RBV AER with RBV PO in the immunocompromised population.20,23,27 The ease of use and decreased cost of RBV PO make it an attractive therapeutic option, although there is very limited data to show improved efficacy over RBV AER. A systematic review of RBV PO in noninfluenza respiratory viral infections reported a mortality ranging from 0 to 31 and 10% to 20% in both the HSCT and the lung transplant population.30 A direct comparison cannot be made with RBV AER, as the population studied included both URTI and LRTI and the severity of illness varied among populations.

The time from diagnosis to the initiation of RBV AER varied widely. In the trials that presented mortality data based on late initiation in relationship to diagnosis or MV, the mortality rates were 27% (3/11) and 100% (9/9), respectively.13,14 Based on these results, prompt diagnosis of RSV LRTI and initiation of RBV AER may improve outcomes. Nevertheless, there may be a time point when the use of RBV AER may not be effective, including patients who develop respiratory failure and are intubated. Some authors hypothesize that this may be due to a decrease in the amount of RBV able to penetrate the lower lung during ventilation or possibly from the amount of RBV that coats the ventilator circuit tubing.6

Only 5 studies commented on the occurrence of ADEs in patients receiving RBV AER.14,22,23,26,27 In studies that reported ADE, the majority were psychiatric in nature. Drug administration via use of a face mask inside a double-tent scavenger system for up to 18 hours per day causes the patient to experience prolonged isolation. Clinicians must consider the psychological effects of therapy including loneliness, anxiety, and depression. Wheezing and bronchospasm were documented in 6 patients, although it is difficult to determine whether the wheezing was a result of RSV LRTI or RBV AER effect on airway resistance. Health care workers and patients should be educated on the potential teratogenic risks, as well as nasal, pharyngeal, bronchial, and/or eye irritation during RBV AER exposure.31 Finally, RBV AER led to precipitation in the ventilator circuit in 5 events. It is important that respiratory policy and procedures are in place before RBV AER therapy is administered. Respiratory therapists must be trained on the appropriate administration technique, as it may vary with specific ventilator types.

Guidance for the treatment of RSV LRTI in adults is available from national and international stakeholders including the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), whom do not recommend antiviral therapy due to the lack of proven value.32 In 2013, the Fourth European Conference on Infections in Leukemia guidelines were published and recommend treating RSV LRTI with RBV AER (2 g over 2 hours every 8 hours or 6 g over 18 hours per day for 7 to 10 days [BII recommendation]) plus IVIG given previous studies suggesting improved outcomes. Oral RBV and intravenous RBV have weaker quality of evidence and strengths of recommendation (BIII and CIII, respectively).33 The 2018 NCCN Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections guidelines (version 1.2019) recommend considering RBV 600 to 800 mg PO twice daily or RBV AER 6 g over 12 to 18 hours daily or 2 g over 2 hours 3 times daily for the treatment of RSV LRTI due to increased risk of mortality in the stem cell transplant or leukemia patient population.34 Due to NCCN panel disagreement, this recommendation carries a category 3 level of evidence. It instructs the decision to use oral versus RBV AER should be individualized by institution.

This systematic review identifies the low quality of evidence that is available to guide therapeutic decisions for treatment of RSV LRTI in hospitalized immunocompromised adults. Identified trends suggest patients receiving more rapid treatment have improved outcomes. If patients and prescribers are willing to accept the psychiatric and respiratory ADEs identified in this review, the last barrier is the rising acquisition cost. Aerosolized RBV has been available since 1985 at an original cost of US $229 per day (6 g vial).35 In 1994, the cost increased to over US $1000 AWP per day of therapy and is currently nearing US $30 000 AWP daily.8,36 The introduction of the generic product and hospital purchasing contracts may result in lower drug acquisition cost. These figures simply represent drug costs and do not include the indirect costs related to the isolation room, drug administration, and nursing and respiratory therapist support. There are new antiviral agents being studied for RSV infection including fusion inhibitors, nucleoside analogs, and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors, but none are currently FDA approved.37,38

Limitations

The limitations of this study are a result of the many limitations present in the included studies, including small sample size, minimal patient demographics, limited information on duration of administered RBV AER, and administration of additional therapies that overall confounds the results. Although not calculated due to the lack of studies with comparator groups, it is evident that there is heterogeneity among the different trials and patient populations. It is also difficult to ascertain the cause of mortality in this high risk population when there are other potential causes for mortality including concomitant bacterial pathogens and underlying comorbidities. Some studies included in this systematic review were performed in the 1980s and the diagnosis of RSV was confirmed by viral culture, since then there have been significant advances with rapid diagnostic testing for RSV disease that should improve time to diagnosis and treatment. In addition, there was some variability in the definition of LRTI and pneumonia in the studies.

Conclusion

There is a lack of comparative trials on the use of RBV AER for the treatment of RSV LRTI in adult hospitalized immunocompromised patients. This systematic review only identified studies in the HSCT/BMT, leukemic, and transplant population. Dosing regimens ranged from 2 g over 2 to 3 hours every 8 hours to 6 g over 12 to 18 hours daily with no standardized durations. No conclusions can be made on the mortality benefit with combination therapy (IVIG and or PZB). There may be a mortality benefit when RBV AER is initiated early after the diagnosis or prior to MV, although this warrants further study. Patient isolation and the resulting psychological effects must be weighed against the benefit of therapy.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lisa Avery  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6304-0593

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6304-0593

References

- 1. Zhou H, Thompson WW, Viboud CG, et al. Hospitalizations associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States, 1993-2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(10):1427-1436. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chartrand C, Tremblay N, Renaud C, Papenburg J. Diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen detection tests for respiratory syncytial virus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(12):3738-3749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01816-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(3):371-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kotloff RM, Ahya VN, Crawford SW. Pulmonary complications of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(1):22-48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1322SO [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. Date unknown. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- 6. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC. Virazole® (Ribavirin) Package Insert. Bridgewater NJ; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neemann K, Freifeld A. Respiratory syncytial virus in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and solid-organ transplantation. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17(7):490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ribavirin oral inhalation. In: UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc; Lexicomp, Inc Topic 105699, Version 44.0. http://www.uptodate.com. Accessed January 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simoes EAF, DeVincenzo JP, Boeckh M, et al. Challenges and opportunities in developing respiratory syncytial virus therapies. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(suppl 1):S1-S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(6): 954-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; www.handbook.cochrane.org. Published March, 2011. Accessed September 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghosh S, Champlin RE, Ueno NT, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in autologous blood and marrow transplant recipients with breast cancer: combination therapy with aerosolized ribavirin and parenteral immunoglobulins. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28(3):271-275. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whimbey E, Champlin RE, Englund JA, et al. Combination therapy with aerosolized ribavirin and intravenous immunoglobulin for respiratory syncytial virus disease in adult bone marrow transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16(3):393-399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCoy D, Wong E, Kuyumjian AG, Wynd MA, Sebti R, Munk GB. Treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in adult patients with hematologic malignancies based on an institution-specific guideline. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13(2):117-121. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bourgouin P, Krakow EF, Roy J, et al. Prompt treatment of respiratory syncytial virus with inhaled ribavirin and IVIG in high risk allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients significantly diminishes mortality. Abstract #293 presented at BMT Tandem Meetings Salt Lake City, UT; February 13-17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mihelic R, Morris L, Holland HK, Bashey A, et al. Early use of inhaled ribavirin can improve outcomes in high risk hematopoietic stem cell transplant and leukemia patients with RSV infection. Abstract #296 Presented at: BMT Tandem Meetings Grapevine, TX; February 24-March 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCarthy AJ, Kingman HM, Kelly C, et al. The outcome of 26 patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24(12):1315-1322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peck AJ, Corey L, Boeckh M. Pretransplantation respiratory syncytial virus infection: impact of a strategy to delay transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(5):673-680. doi: 10.1086/422994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foolad F, Aitken SL, Shigle TL, et al. Oral versus aerosolized ribavirin for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients [published online ahead of print September 8, 2018]. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torres HA, Aguilera EA, Mattiuzzi GN, et al. Characteristics and outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92(9):1216-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whimbey E, Couch RB, Englund JA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia in hospitalized adult patients with leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(2):376-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ariza-Heredia EJ, Fishman JE, Cleary T, Smith L, Razonable RR, Abbo L. Clinical and radiological features of respiratory syncytial virus in solid organ transplant recipients: a single-center experience. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14(1):64-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer SM, Jr, Henshaw NG, Howell DN, Miller SE, Davis RD, Tapson VF. Community respiratory viral infection in adult lung transplant recipients. Chest. 1998;113(4):944-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zamora MR, Hodges T, Nicolls MR, Astor TL, Marquesen J, Weill D. Impact of respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia following lung transplantation: a case-controlled study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(2 suppl):S43-S44. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li L, Avery R, Budev M, Mossad S, Danziger-Isakov L. Oral versus inhaled ribavirin therapy for respiratory syncytial virus infection after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(8):839-844. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trang TP, Whalen M, Hilts-Horeczko A, Doernberg SB, Liu C. Comparative effectiveness of aerosolized versus oral ribavirin for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infections: a single-center retrospective cohort study and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20(2):e12844. doi: 10.1111/tid.12844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anderson NW, Binnicker MJ, Harris DM, et al. Morbidity and mortality among patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection: a 2-year retrospective review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85(3):367-371. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shah JN, Chemaly RF. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(10):2755-2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-263400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gross AE, Bryson ML. Oral ribavirin for the treatment of noninfluenza respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(10):1125-1135. doi: 10.1177/1060028015597449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liss HP, Bernstein J. Ribavirin aerosol in the elderly. Chest. 1988;93(6):1239-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Disease Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S27-S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hirsch HH, Martino R, Ward KN, Boeckh M, Einsele H, Ljungman P. Fourth European conference on infections in leukemia (ECIL-4): guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and coronavirus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(2):258-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections (Version 1.2019). Date unknown. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- 35. Anon. Ribavirin (Virazole). Med Lett. 1986;28(712):46-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chemaly RF, Aitken SL, Wolfe CR, Jain R, Boeckh MJ. Aerosolized ribavirin: the most expensive drug for pneumonia. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18(4):634-636. doi: 10.1111/tid.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mejias A, Ramilo O. New options in the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Infect. 2015;71(suppl 1):S80-S17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pareek R, Murphy R, Harrison L, et al. In vitro superiority of RSV fusion inhibitor MDT-637 vs ribavirin predicts improved clinical benefit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):954. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000440192.15654.2d23385106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]