Abstract

Background: There are no clearly defined guidelines from hand surgical societies regarding preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis. Many hand surgeons continue to routinely use preoperative prophylaxis with limited supporting evidence. This study aimed to determine for which scenarios surgeons give antibiotics, the reasons for administration, and whether these decisions are evidence-based. Methods: An anonymous 25-question survey was e-mailed to the 921-member American Society for Surgery of the Hand listserv. We collected demographic information; participants were asked whether they would administer antibiotics in a number of surgical scenarios and for what reasons. Respondents were broken into 3 groups based on when they said they would administer antibiotics: Group 1 (40 respondents) would give antibiotics in the case of short cases, healthy patients, without hardware; group 2 (9 respondents) would not give antibiotics in any scenario; and group 3 (129 respondents) would give antibiotics situationally. The Fisher exact test compared demographic variables, frequency of use, and indications of antibiotic prophylaxis. Results: Of the 921 recipients, 178 (19%) responded. Demographic variables did not correlate with the antibiotic use group. Operative case time >60 minutes, medical comorbidity, and pinning each increased antibiotic use. Group 1 respondents were more likely to admit that their practice was not evidence-based (74.4%) and that they gave antibiotics for medical-legal concern (75%). Twenty-two percent of respondents reported seeing a complication from routine prophylaxis, including Clostridium difficile infection. Conclusions: Antibiotics are still given unnecessarily before hand surgery, most often for medical-legal concern. Clear guidelines for preoperative antibiotic use may help reduce excessive and potentially inappropriate treatment and provide medical-legal support.

Keywords: antibiotic prophylaxis, decision making, evidence-based practice, perioperative antibiotics, hand surgery

Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis regimens have been well described in hip,1-3 knee,4,5 and shoulder arthroplasty,6,7 as well as in orthopedic trauma.8,9 There are no specific guidelines from hand surgical societies regarding preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis.9,10 This may be, in part, due to the low rate of surgical site infection (SSI), which is generally reported as less than 1%.11-17 Even considering this overall low incidence, studies have shown no difference in rates of infection after hand surgery between antibiotic prophylaxis and no prophylaxis.10,18-21 Unnecessary routine antibiotic use may be detrimental to both the patient and the society as this practice may induce Clostridium difficile infection, allergic reaction, and antibiotic resistance.22,23

There is no evidence to strongly support using prophylaxis in hand surgery cases for repair of lacerations,24-26 clean hand injuries,19,21 small joint replacements,17,27 and complex hand trauma28-30; for patients with associated medical comorbidities17,27,31,32; or for cases that last less than 2 hours.19,21 Even pinning of fractures may not require antibiotic prophylaxis.33

Furthermore, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has recommended against using antimicrobial prophylaxis for clean hand procedures without implantation of foreign materials (strength of evidence against prophylaxis: C).34 Despite the evidence against routine antibiotic prophylaxis in hand surgery, antibiotics are given preoperatively in 10% to 30% of clean, elective hand procedures.10,35,36 The factors associated with unnecessary antibiotic treatment in hand surgery are not known. The primary aims of this study are to determine for which scenarios surgeons give antibiotics, the reasons for administration, and whether these decisions are evidence-based.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, a 25-question survey was sent via e-mail to the 921-member American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) listserv. The listserv is an ASSH member and candidate member e-mail chain used to interact, discuss challenging cases, and share clinical and surgical tips. The ASSH listserv membership includes attending surgeons, fellows, and residents. We created our survey with SurveyMonkey and posted it to the listserv twice over the course of 6 weeks. A link was provided in the e-mail that redirected the anonymous participant to the survey. To encourage participation, we announced that a US $500 prize would be awarded to a randomly chosen participant. No participant from our home institution was eligible to win the prize. Surgeons were only allowed to answer the survey once.

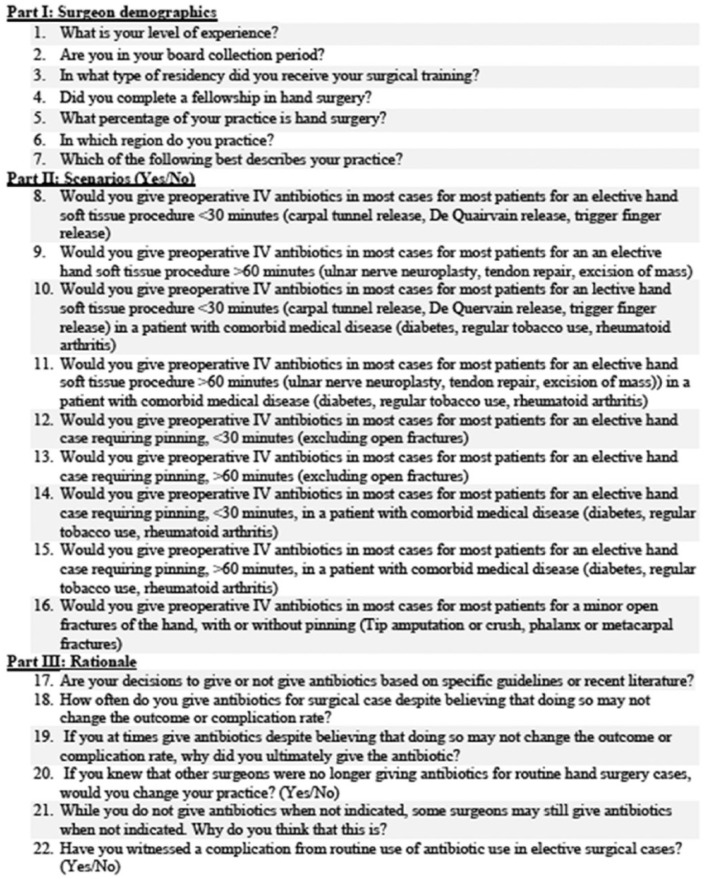

The survey questions were developed by the primary and senior author and are provided in Figure 1. The survey questions sought to determine whether any demographic factors correlated with scenario response. The scenarios were modeled after the stratification of prior prospective studies18 and retrospective reviews.10,11 We also asked whether the participant had already taken the survey, whether there was additional information they wanted to share, and for a contact address if they wanted to participate in the random drawing for the prize. Based on the survey responses, participants were divided into 3 groups. Group 1 chose to give antibiotics for question 8 scenario (in cases <30 minutes, a healthy patient, without pinning). Group 2 chose not to give antibiotics in any scenario. Group 3 chose to give antibiotics in some, but not all, scenarios.

Figure 1.

Participant survey.

Note. IV = intravenous.

Demographic variables, frequency of use by group, and indications of antibiotic prophylaxis were tabulated and compared using the Fisher exact test (Tables 1 and 2). For group 3, the varied use group, we reported percentages of antibiotic use for each scenario (Table 3). To determine which factors caused surgeons in group 3 to give antibiotics, we performed analysis using the McNemar test for comparison of marginal proportions of paired observations (Table 4).

Table 1.

Demographic Variables.

| Variable | Total | Group 1 (n = 40) | Group 2 (n = 9) | Group 3 (n = 129) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of experience (n = 178) | .40 | ||||

| Resident or fellow | 6 (3.4) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.9) | |

| In practice <5 years | 38 (21.3) | 8 (20) | 0 (0) | 30 (23.3) | |

| In practice 5-20 years | 60 (33.7) | 15 (37.5) | 2 (22.2) | 43 (33.3) | |

| In practice >20 years/retired | 74 (41.6) | 16 (40) | 7 (77.8) | 51 (39.5) | |

| Completed fellowship (n = 172) | .82 | ||||

| No | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Yes | 171 (99.4) | 39 (100) | 9 (100) | 123 (99.2) | |

| In board collection period (n = 172) | .48 | ||||

| No | 163 (94.8) | 36 (92.3) | 8 (88.9) | 119 (96) | |

| Yes | 9 (5.2) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (4) | |

| Type of residency (n =178) | .37 | ||||

| General surgery | 6 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (3.9) | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 153 (86) | 36 (90) | 8 (88.9) | 109 (84.5) | |

| Plastic surgery | 19 (10.7) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 15 (11.6) | |

| Percentage of hand surgery (n = 178) | .68 | ||||

| <50% | 5 (2.8) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.1) | |

| 50%-80% | 35 (19.7) | 7 (17.5) | 1 (11.1) | 27 (20.9) | |

| 80%-90% | 29 (16.3) | 10 (25) | 1 (11.1) | 18 (14) | |

| >90% | 109 (61.2) | 22 (55) | 7 (77.8) | 80 (62) | |

| Type of practice (n =178) | .25 | ||||

| Academic | 17 (9.6) | 7 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (7.8) | |

| Employed/limited academic | 20 (11.2) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (11.1) | 18 (14) | |

| Military | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.1) | |

| Private | 130 (73) | 31 (77.5) | 8 (88.9) | 91 (70.5) | |

| Training (resident/fellow) | 7 (3.9) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Region (n = 177) | .82 | ||||

| Atlantic (NY, NJ, PA, MD, DE, DC, WV) | 32 (18.1) | 6 (15) | 1 (11.1) | 25 (19.5) | |

| Great Lakes (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI, MN) | 31 (17.5) | 5 (12.5) | 1 (11.1) | 25 (19.5) | |

| New England (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT) | 10 (5.6) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (6.2) | |

| Pacific (AK, CA, HI, OR, WA) | 28 (15.8) | 9 (22.5) | 1 (11.1) | 18 (14.1) | |

| South (FL, GA, NC, SC, VA, AR, LA) Al, KY MS, TN) | 45 (25.4) | 11 (27.5) | 3 (33.3) | 31 (24.2) | |

| Southwest (TX, OK, NM, NV, UT, CO, AZ) | 21 (11.9) | 4 (10) | 1 (11.1) | 16 (12.5) | |

| West (IA, KS, MO, ND, NE, SD, ID, MT, WY) | 10 (5.6) | 4 (10) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (3.9) |

Note. The numbers in parentheses are the percentage distribution for each subgroup.

Table 2.

Surgeons in the Sometime User Group (Group 3, Total n = 129) Who Chose to Use Antibiotics in Each Case Scenario.

| Question (case factor) | No. from group 3 (%) |

|---|---|

| Question 8 (<30 min) | 0 (0.0) |

| Question 9 (>60 min) | 64 (50) |

| Question 10 (<30 min + comorbidity) | 57 (44) |

| Question 11 (>60 min + comorbidity) | 101 (78) |

| Question 12 (<30 min + pinning) | 102 (79) |

| Question 13 (>60 min + pinning) | 116 (90) |

| Question 14 (<30 min + pinning + comorbidity) | 111 (86) |

| Question 15 (>60 min + pinning + comorbidity) | 121 (94) |

| Question 16 (minor open fracture with or without pinning) | 116 (90) |

Table 3.

Comparative Analysis of Sometime Users (Group 3; n = 129): Percentage of Surgeons Who Chose to Use Antibiotics by Each Pertinent Case Variable.

| Adding an additional factor | % change | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 min | > 60 min | |||

| Comorbidity + nonpinning | 57 (44%) | 101 (78%) | 34 | <.001 |

| Comorbidity + pinning | 111 (86%) | 121 (94%) | 8 | .004 |

| Noncomorbidity + pinning | 102 (79%) | 116 (90%) | 11 | <.001 |

| Average | 18 | |||

| Noncomorbidity | Comorbidity | |||

| >60 min + pinning | 116 (90%) | 121 (94%) | 4 | .07 |

| >60 min + nonpinning | 64 (50%) | 101 (78%) | 29 | <.001 |

| <30 min + pinning | 102 (79%) | 111 (86%) | 7 | .01 |

| Average | 13 | |||

| Nonpinning | Pinning | |||

| <30 min + comorbidity | 57 (44%) | 111 (86%) | 42 | <.001 |

| >60 min + comorbidity | 101 (78%) | 121 (94%) | 16 | <.001 |

| >60 minutes + noncomorbidity | 64 (50%) | 116 (90%) | 40 | <.001 |

| Average | 33 | |||

Note. For any given 2 questions with 2 factors in common, this table compares proportions of subjects who said yes to antibiotic use in a scenario between 2 levels of the third factor. The McNemar test for comparison of marginal proportions of paired observations was utilized.

Bolded items represent significant findings with P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Additional Questions on Frequency, Evidence, Indications, and Complications From Antibiotic Prophylaxis.

| Question | Total responses (% of all responders) | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is your decision on antibiotic prophylaxis based on scientific evidence? | ||||

| Yes | 89 (50) | 10 (26) | 6 (67) | 72 (56) |

| No | 88 (50) | 29 (74) | 3 (33) | 57 (44) |

| How often do you give antibiotics despite thinking that it will not affect outcomes? | ||||

| Often (once per day) | 17 (45) | 2 (22) | 19 (15) | |

| Sometimes (once per week) | 13 (34) | 0 | 44 (34) | |

| Rarely (once per month) | 5 (13) | 4 (44) | 51 (40) | |

| Never | 3 (8) | 3 (33) | 15 (12) | |

| Why did you ultimately give the antibiotic unnecessarily? | ||||

| Antibiotic given without my consent | 41 (27) | 5 (14) | 1 (17) | 35 (31) |

| Belief that current evidence is insufficient | 40 (26) | 14 (39) | 0 (0) | 26 (23) |

| Concern about board collection period | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Hospital policy | 42 (27) | 16 (44) | 2 (33) | 24 (21) |

| Medical-legal concern | 91 (59) | 27 (75) | 2 (33) | 62 (54) |

| Other surgeons practice in this manner | 26 (17) | 7 (19) | 1 (17) | 18 (16) |

| Unaware of recommended indications | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.6) |

| Other | 24 (16) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | 20 (18) |

| Unsure | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) |

| Witnessed a complication from antibiotic | 39 (23) | 7 (19) | 2 (22) | 30 (24) |

Results

Of the 921 ASSH listserv recipients, 178 (19%) participated and were subsequently divided into 3 groups. The groups included group 1 (40 respondents) who gave antibiotics in the case of short cases, healthy patients, without hardware; group 2 (9 respondents) who never gave antibiotics; and group 3 (129 respondents) who sometimes gave antibiotics. Level of experience, fellowship training, type of residency training, volume of hand surgery within one’s practice, type of practice, and geographic region did not correlate with a particular group of antibiotic use (Table 1).

Among surgeons in group 3, antibiotic use for the different scenarios ranged from never (cases <30 min, without comorbidity or pinning) to 94% (cases >60 minutes, with comorbidity and pinning) (Table 2). The impact of each factor (length of case, medical comorbidity, and pinning) was reviewed from all scenarios and compared for influence on frequency of antibiotic use. Although each of the 3 factors affected the likelihood of antibiotic use in group 3, pinning was the single most impactful factor. Every factor significantly increased antibiotic use in every scenario (P < .05) except for the addition of a medical comorbidity to a case greater than 60 minutes in which pins were used (94% vs 90%; P = .07) (Table 3).

Although 50% of all participants reported their decision on prophylaxis as evidence-based, the majority of group 1 respondents (74%) admitted that their practice was not evidence-based (P = .002). The most frequently reported reason for unnecessary prophylaxis was medical-legal concern (59%), which was most notable in group 1 (75%) (P = .03). Other common reasons for unnecessary prophylaxis included antibiotics given without surgeon’s consent (27%), hospital policy (27%), belief that the current evidence to not give antibiotics is insufficient (26%), and that other surgeons practice in this manner (17%). Other factors for use included a patient’s prior history of infection, belief that benefits outweigh the risks, patients with implants like a total joint arthroplasty, and patient request (Table 4).

Nearly one-quarter (23%) of responding surgeons have witnessed a complication that they attributed to antibiotic use in hand surgery (Table 2). These included Clostridium difficile infection (16 cases, 9%), diarrhea (9 cases, 5%), rash (8 cases, 4%), anaphylaxis (5 cases), “Redman” Syndrome (3 cases), superimposed infection (2 cases), and death (1 case).

Discussion

This survey study assessing the frequency and indications of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis by hand surgeons has 3 key findings. First, 23% of respondents chose to give antibiotics in clean hand surgery cases of less than 30 minutes, healthy patients, that did not involve hardware (group 1). This group was significantly more likely to admit their practice as not evidence-based (74%) and to have their prophylaxis decisions precipitated by medical-legal concern (75%). Second, the majority of respondents (73%) chose to give antibiotics only during some of the scenarios, and the frequency of prophylaxis in this cohort (group 3) was increased by longer operative time, medical comorbidity, and pinning. Third, 23% of respondents reported witnessing a complication from antibiotic prophylaxis, including 9% who had patients develop a Clostridium difficile infection.

Of the 23% of hand surgeons who reported they would administer preoperative antibiotics in short, clean cases—healthy patients—without hardware, 79% reported doing so at least once per week. This rate is comparable to the 31% of patients who received unnecessary prophylaxis in a retrospective review from a large academic hand center.10 In that review of SSI following clean elective hand cases, administering antibiotics did not change the rate of SSI, even in the presence of medical comorbidity and longer operative time. Furthermore, in a prospective trial including 1340 patients undergoing a variety of hand surgery procedures (clean and dirty, elective and emergent, with and without hardware), patients were randomized either to preoperative intravenous cephalosporin or placebo.18 No difference was found in the infection rate between preoperative antibiotic use and placebo in any scenario. The authors concluded that their findings do not support prophylaxis except in particular conditions under which a specific patient may have a high baseline infection risk. A well-conducted meta-analysis11 and a large database review from an American insurance repository36 concluded that preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis does not lower the risk of SSI while controlling for patient and surgical risk factors. Despite these findings, one recent review found an increase in antibiotic use in hand surgery by 73% between 2009 and 2015.35

Our survey suggests that medical-legal concerns are driving preoperative antibiotic decisions for those hand surgeons who are not following the current best evidence available. Pressure from medical litigation has changed the way hand surgeons practice,37,38 and considering that SSI is a common cause of litigation,39 medical-legal concern may be seen as a reasonable cause for surgeons to give antibiotics. Although it is understandable for surgeons to tailor their practice in an attempt to reduce the likelihood of litigation, it is relieving to note that claims against hand surgeons in general are rare and most often unsuccessful. In a review of 23 legal cases relating to hand trauma from a single institution in New York City over an 8-year period, the authors found that only 1 patient won a settlement.40 Specific guidelines from professional societies on the standard of care for antibiotic use in hand surgery may help clarify the current evidence against routine prophylaxis and lessen medical-legal concerns among surgeons.

Not all participants in this survey gave antibiotics readily, as most respondents (72%) gave antibiotics only during some of the 9 scenarios. Gaps in the evidence may precipitate a wide spectrum of practice regarding antibiotic prophylaxis in hand surgery. In the previously detailed prospective randomized controlled trial by Aydin et al,18 patients with comorbid medical conditions were excluded and it is unclear whether the study was powered appropriately to ascertain small differences in infection rates in the hardware group. In addition, the retrospective review of antibiotic use by Bykowski and colleagues excluded all procedures with hardware.10 These notable omissions limit our ability to delineate appropriate comprehensive evidence-based guidelines.

Hand surgeons are correct to scrutinize their practice of antibiotic use because routine prophylaxis involves a certain degree of risk. Twenty-three percent of the respondents in our study have witnessed a complication that they attributed to antibiotic use. In one retrospective analysis of general, cardiac, and vascular surgery in Quebec, the incidence of Clostridium difficile infection was 1.5% following perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis.22 For this reason, the authors recommended against prophylaxis in cases where infection is infrequent and benign. Recent prospective randomized controlled trials have also suggested that routine prophylaxis is not necessary in certain abdominal41 and urological cases.42 Reducing unnecessary prophylaxis in hand surgery would serve to reduce the development of complications, as well as subsequent superinfection and antibiotic resistance.

Our study has limitations. The methods of the survey collection are imperfect. The ASSH listserv represents less than a third of the members of the ASSH. There is a barrier to entry onto the listserv, as to receive the e-mails one must sign up on the ASSH website and be approved. Thus, it is possible that the listserv members are not representative of all ASSH members or of all surgeons who perform hand surgery. In addition, the survey response rate was low (19%), which further potentiates the sampling bias. It is possible that the most conscientious of hand surgeons subscribe to the listserv and the most dedicated of these will view and ultimately respond to the survey requests. Although our response rate is low compared with traditional methods,43 it is comparable to other studies with similar methods. Even after sending up to 6 e-mails, the online response rate in other studies with analogous methods has ranged from 11% to 26%.44-46 We chose the online survey for its ease of use, low cost, and efficiency, which may have limited our findings and the transferability of our results. Furthermore, the surgeon responses are subject to the Hawthorne effect and may not reflect actual choices made in patient care.47 This is the effect of feeling pressured to choose the “correct” answer instead of choosing what one may actually do when presented with the same scenario in actual practice. For this reason, it is possible that antibiotic use was underestimated in the present survey. In addition, all respondents are subject to recall bias with regard to complications following prophylaxis.

Despite these limitations, the present analysis provides a snapshot of current antibiotic prophylaxis in hand surgery. Nearly a quarter of surgeons give prophylaxis when it is likely not indicated. The majority (74%) are aware of the lack of evidence to support this practice but make these choices based on medical-legal concern (75%). In addition, many report antibiotics being given without their consent (27%), state that their hospital policy dictates use (27%), believe that the current evidence is insufficient (26%), or simply do so because they believe other surgeons also use unnecessary prophylaxis (17%). To limit inappropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, the hand surgery community must widen the inclusion criteria on studies of antibiotic prophylaxis, improve the education of practicing surgeons and trainees regarding antibiotic prophylaxis, and look to develop clear and specific evidence-based guidelines that could be easily and universally adopted.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army, Department of Defense, or US Government.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: Not applicable to this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Raymond M. Curtis Research Foundation, (grant number JCD-2017), MedStar IRB 2017-241, The Curtis National Hand Center, Baltimore, Maryland.

ORCID iDs: Kenneth R. Means Jr  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9040-357X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9040-357X

Aviram M. Giladi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7688-957X

References

- 1. AlBuhairan B, Hind D, Hutchinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis for wound infections in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:915-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ericson C, Lidgren L, Lindberg L. Cloxacillin in the prophylaxis of postoperative infections of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:808-813,843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hill C, Flamant R, Mazas F, et al. Prophylactic cefazolin versus placebo in total hip replacement. Report of a multicentre double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1981;1:795-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of 56,216 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:775-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu CT, Chen IL, Wang JW, et al. Surgical site infection after total knee arthroplasty: risk factors in patients with timely administration of systemic prophylactic antibiotics. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1568-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu JE, Bumgarner RE, Matsen FA., III Propionibacterium in shoulder arthroplasty: what we think we know today. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:597-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saltzman MD, Marecek GS, Edwards SL, et al. Infection after shoulder surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:208-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyd RJ, Burke JF, Colton T. A double-blind clinical trial of prophylactic antibiotics in hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1251-1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burnett JW, Gustilo RB, Williams DN, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics in hip fractures. A double-blind, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:457-462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bykowski MR, Sivak WN, Cray J, et al. Assessing the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis in outpatient elective hand surgery: a single-center, retrospective review of 8,850 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1741-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ariyan S, Martin J, Lal A, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing surgical-site infection in plastic surgery: an evidence-based consensus conference statement from the American Association of Plastic Surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:1723-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanssen AD, Amadio PC, DeSilva SP, et al. Deep postoperative wound infection after carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:869-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleinert JM, Hoffmann J, Miller CG, et al. Postoperative infection in a double-occupancy operating room. a prospective study of two thousand four hundred and fifty-eight procedures on the extremities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:503-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lipira AB, Sood RF, Tatman PD, et al. Complications within 30 days of hand surgery: an analysis of 10,646 patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:1852-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schneider LH, Hunter JM, Norris TR, et al. Delayed flexor tendon repair in no man’s land. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2:452-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stepan JG, Boddapati V, Sacks HA, et al. Insulin dependence is associated with increased risk of complications after upper extremity surgery in diabetic patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:745-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swanson AB. Flexible implant arthroplasty for arthritic finger joints: rationale, technique, and results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:435-455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aydin N, Uraloglu M, Yilmaz Burhanoglu AD, et al. A prospective trial on the use of antibiotics in hand surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1617-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henley MB, Jones RE, Wyatt RW, et al. Prophylaxis with cefamandole nafate in elective orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;209:249-254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Platt AJ, Page RE. Post-operative infection following hand surgery: guidelines for antibiotic use. J Hand Surg Br. 1995;20:685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Whittaker JP, Nancarrow JD, Sterne GD. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis in clean incised hand injuries: a prospective randomized placebo controlled double blind trial. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carignan A, Allard C, Pepin J, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile infection after perioperative antibacterial prophylaxis before and during an outbreak of infection due to a hypervirulent strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1838-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shapiro S, Siskind V, Slone D, et al. Drug rash with ampicillin and other penicillins. Lancet. 1969;2:969-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grossman JA, Adams JP, Kunec J. Prophylactic antibiotics in simple hand lacerations. JAMA. 1981;245:1055-1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haughey RE, Lammers RL, Wagner DK. Use of antibiotics in the initial management of soft tissue hand wounds. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberts AH, Teddy PJ. A prospective trial of prophylactic antibiotics in hand lacerations. Br J Surg. 1977;64:394-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blair WF, Shurr DG, Buckwalter JA. Metacarpophalangeal joint implant arthroplasty with a Silastic spacer. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:365-370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fitzgerald RH, Jr, Cooney WP, III, Washington JA, et al. Bacterial colonization of mutilating hand injuries and its treatment. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2:85-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peacock KC, Hanna DP, Kirkpatrick K, et al. Efficacy of perioperative cefamandole with postoperative cephalexin in the primary outpatient treatment of open wounds of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:960-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Suprock MD, Hood JM, Lubahn JD. Role of antibiotics in open fractures of the finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15:761-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Culver DH, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, et al. Surgical wound infection rates by wound class, operative procedure, and patient risk index. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Am J Med. 1991;91:152-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lidgren L. Postoperative orthopaedic infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. Acta Orthop Scand. 1973;44:149-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Botte MJ, Davis JL, Rose BA, et al. Complications of smooth pin fixation of fractures and dislocations in the hand and wrist. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;276:194-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:195-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson SP, Zhong L, Chung KC, et al. Perioperative antibiotics for clean hand surgery: a national study. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:407-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li K, Sambare TD, Jiang SY, et al. Effectiveness of preoperative antibiotics in preventing surgical site infection after common soft tissue procedures of the hand. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:664-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Couldwell WT, Gottfried ON, Weiss MH, et al. Too many? too few. Amer Assoc Neurol Surg Bulletin. 2003;12:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kessler FB. Hand surgery and the medical liability issue. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18:557-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mouton J, Gauthe R, Ould-Slimane M, et al. Litigation in orthopedic surgery: what can we do to prevent it? systematic analysis of 126 legal actions involving four university hospitals in France. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104:5-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bastidas N, Cassidy L, Hoffman L, et al. A single-institution experience of hand surgery litigation in a major replantation center. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:284-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruangsin S, Laohawiriyakamol S, Sunpaweravong S, et al. The efficacy of cefazolin in reducing surgical site infection in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:874-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harmanli O, Boyer RL, Metz S, et al. Double-blinded randomized trial of preoperative antibiotics in midurethral sling procedures and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1249-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drolet BC, Marwaha JS, Hyatt B, et al. Electronic communication of protected health information: privacy, security, and HIPAA compliance. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42:411-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reinisch JF, Yu DC, Li WY. Getting a valid survey response from 662 plastic surgeons in the 21st century. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:3-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30:303-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mangione-Smith R, Elliott MN, McDonald L, et al. An observational study of antibiotic prescribing behavior and the Hawthorne effect. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1603-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]