SUMMARY

CSF-1R haploinsufficiency causes adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP). Previous studies in the Csf1r+/− mouse model of ALSP hypothesized a central role of elevated cerebral Csf2 expression. Here, we show that monoallelic deletion of Csf2 rescues most behavioral deficits and histopathological changes in Csf1r+/− mice by preventing microgliosis and eliminating most microglial transcriptomic alterations, including those indicative of oxidative stress and demyelination. We also show elevation of Csf2 transcripts and of several CSF-2 downstream targets in the brains of ALSP patients, demonstrating that the mechanisms identified in the mouse model are functional in humans. Our data provide insights into the mechanisms underlying ALSP. Because increased CSF2 levels and decreased microglial Csf1r expression have also been reported in Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis, we suggest that the unbalanced CSF-1R/CSF-2 signaling we describe in the present study may contribute to the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative conditions.

In Brief

ALSP is a dementia caused by dominantly inherited inactivating mutations in the CSF1R. Chitu et al. report that CSF2 expression is increased in ALSP patients. Targeting Csf2 in ALSP mice prevents behavioral deficits and callosal atrophy and reduces demyelination by normalizing microglial function, identifying CSF-2 as a potential therapeutic target in ALSP.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) is regulated by two cognate ligands, CSF-1 and interleukin-34; is expressed on microglia; and is required for their development and maintenance (reviewed in Chitu et al., 2016). Recent studies show that microglia play important roles in the regulation of neuronal development, learning-dependent synaptic pruning, and oligodendrogenesis (Chitu et al., 2016; Hagemeyer et al., 2017). Thus, the microglial CSF-1R may non-cell-autonomously regulate neural lineage cells.

Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP), also known as hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia or pigmented orthochromatic leukodystrophy, is an autosomal-dominant, neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations of the CSF1R gene (reviewed in Konno et al., 2018). ALSP is characterized by dementia with neuropsychiatric and motor deficits and has an average disease duration of 6.8 years. The discovery of an ALSP patient with a CSF1R frameshift mutation that abolished CSF-1R protein expression proved that CSF1R haploinsufficiency is sufficient to cause ALSP (Konno et al., 2014).

Similar to ALSP patients, Csf1r+/− mice exhibit behavioral, radiological, histopathological, and ultrastructural alterations associated with microgliosis and demyelination (Chitu et al., 2015). Microgliosis occurred in the absence of a compensatory increase in the expression of CSF-1R ligands. However, in both presymptomatic and diseased mice, microgliosis was associated with an increase in expression of mRNA of the proinflammatory microglial mitogen colony-stimulating factor-2 (CSF-2), also known as granulocyte macrophage CSF (GM-CSF) (Chitu et al., 2015). In the present study, we show that CSF2 expression is also increased in the brains of ALSP patients, and we examine the effect of removal of a single Csf2 allele on development of ALSP in Csf1r+/− mice.

RESULTS

Monoallelic Targeting of Csf2 Prevents White Matter Microgliosis in Young Csf1r+/− Mice

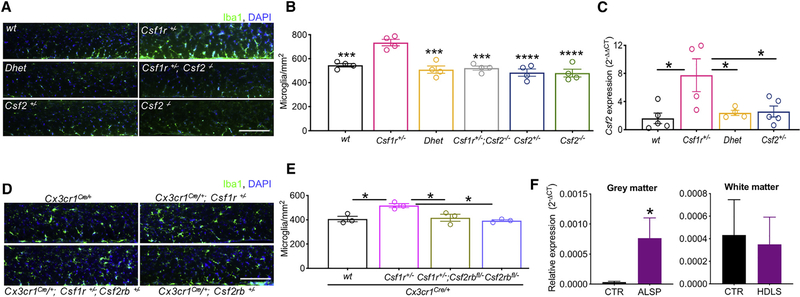

Because CSF-2 is a microglial mitogen (Lee et al., 1994), and Csf1r+/− mice exhibit early-onset microgliosis (Chitu et al., 2015), we initially examined the effect of genetic targeting of Csf2 on Iba-1+ microglia density in young Csf1r+/− mice. Mono-allelic targeting was sufficient to normalize Csf2 mRNA expression and to lower the microglial density in Csf1r+/− mice to wild-type levels (Figures 1A–1C). Csf2 homozygous deletion showed no additional effects over Csf2 heterozygosity. Consistent with the low abundance of Csf2 transcripts in wild-type brains (Figure 1C), Iba-1+ cell densities in Csf2+/− and Csf2−/− mice were not different from those of wild-type mice (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Involvement of CSF-2 in the Pathology of ALSP.

(A) Microglial densities in the corpus callosum of 4- to 5-month-old mice.

(B) Quantification of microglial densities. Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test.

(C) Restoration of normal Csf2 expression in 3- to 4-month-old Csf1r+/− mice by monallelic targeting of Csf2. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(D and E) Evidence of direct regulation of the increase of Iba1+ cell density by Csf2. Microglial densities (D) and quantification (E). Data ± SEM, 3-month-old mice, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

(F) Expression of CSF2 in the periventricular white matter and adjacent gray matter of ALSP patients and healthy controls, determined by real-time qPCR and normalized to RPL13. n = 5 control or ALSP specimens; *p < 0.05, one- tailed Student’s t test.

Scale bars, 100 μm, applies to all panels in the corresponding composite image. Data are presented as means ± SEM, and only the significantly different changes are marked by asterisks. See also Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S9.

To investigate whether CSF-2 drives microgliosis in ALSP mice directly by stimulating its receptor in microglia, we used the Cx3Cr1Cre/+ gene targeting system (Yona et al., 2013; Goldmann et al., 2013) to delete a Csf2rb allele (Croxford et al., 2015) in myeloid cells and microglia. The mice were examined at 3 months of age, when there is no evidence of demyelination or other pathological changes (Figure S1) that could confound interpretation of the results. Similar to Csf2 heterozygosity, conditional deletion of a single Csf2rb allele was sufficient to prevent white matter microgliosis in young Csf1r+/− mice without altering microglial densities in the wild-type background (Figures 1D and 1E). These data indicate that CSF-2 causes microgliosis in the ALSP model via direct stimulation of microglia.

Increased Expression of CSF2 in the Brains of ALSP Patients

To investigate whether CSF2 was elevated in the human disease, we examined the expression of CSF2 in the periventricular white matter and adjacent gray matter of 5 ALSP patients and 5 matched controls (Table S1). Consistent with the results obtained in mice, the levels of CSF2 transcripts were almost undetectable in control patients, whereas CSF2 expression was increased in the gray matter of ALSP patients (Figure 1F).

Monoallelic Csf2 Inactivation Prevents Loss of Spatial Memory in ALSP Mice

The normalization of microglial density in young mice prompted us to determine the effect of monoallelic Csf2 inactivation on the development of behavioral deficits in older Csf1r+/− mice. Regardless of genotype, the body weight of males and females increased with age without significant genotype-associated differences (Figure S2), and there were no significant differences in survival up to 18 months of age. To test the effect of Csf2 heterozygosity on short-term spatial memory, we used object recognition, object placement, and Y-maze paradigms. In the object recognition test, deficits observed in Csf1r haploinsufficient mice at 7 months of age were prevented by Csf2 heterozygosity (double heterozygous [Dhet]) (Figure 2A). In the Y-maze (Figure 2B) and object placement (Figure 2C) tests, deficits apparent at 13–15 months in Csf1r haploinsufficient mice were also prevented by Csf2 heterozygosity. Interestingly, in the latter two tests, deficits were also present in Csf2 heterozygous mice. Similar results were obtained at 16.5 months of age in a test of long-term memory (object recognition with a 24-h retention interval; Figure 2D). Again, in these older mice, a deficit became apparent in Csf2 heterozygous mice. These results demonstrate prevention of short- and long- term spatial memory deficits of Csf1r+/− ALSP mice by Csf2 heterozygosity. However, they also show that Csf2 heterozygosity on a wild-type (WT) background results in spatial memory deficits with aging.

Figure 2. Deletion of a Single Csf2 Allele Prevents the Cognitive Deficit and Depression in ALSP (Csf1r+/−) Mice.

(A–D) Cognitive assessment. The test performed, age of the mice, and retention interval (RI) are indicated in each panel. The number of mice per genotype in each experiment is shown in the bars in the left panel.

(A) Left (training): preference for the left side by Csf1r+/− mice exploring two familiar identical objects. Right (testing): Csf1r+/− mice spent less time exploring the novel object (left side).

(B) Left: similar exploration of the arms of the Y-maze in all experimental groups. Right: lower discrimination for the novel arm by Csf1r+/− mice is corrected in Csf1r+/−; Csf2+/− (Dhet) mice.

(C) Left: all experimental groups exhibited similar times of exploration of either object. Right: lower preference for the displaced object by Csf1r+/− mice is corrected in Dhet mice.

(D) Left (training): all experimental groups exhibited similar times of exploration of two familiar identical objects. Right (testing): reduced long-term memory for the novel object by Csf1r+/− mice was corrected in Dhet mice.

(E) Increased depression-like behavior in male Csf1r+/− mice is corrected in Dhet mice.

Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s (A–C); Holm-Sidak’s (D); or Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli’s (E) post hoc tests. The left panel in (B) was analyzed by one-way ANOVA (not significant). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Csf2 Heterozygosity Prevents Depression-like Behavior in Male ALSP Mice

Previous studies demonstrated male-specific, depression-like behavior in Csf1r+/− mice (Chitu et al., 2015). This phenotype was reproduced with males in the current cohort and prevented by Csf2 heterozygosity (Figure 2E).

Monoallelic Csf2 Inactivation Prevents Olfactory Dysfunction in ALSP Mice

Because Csf1r+/− mice exhibit olfactory deficits (Chitu et al., 2015), we explored the contribution of CSF-2 to this phenotype in an odor discrimination test (Figure 3A). Mice of all genotypes exhibited lower exploration of the repulsive odorant and trigeminal stimulant, lime, compared with the attractive pure odorant, vanilla. However, in response to vanilla, WT mice increased their exploration with time, whereas Csf1r+/− mice failed to do so. This phenotype of Csf1r+/− mice was corrected by Csf2 heterozygosity. To further explore the olfactory response of Csf1r+/− mice to pure odorants, we subjected the mice to an odor threshold assay (Witt et al., 2009) using 2-phenylethanol (Doty et al., 1978; Figure 3B). Although WT control mice were able to detect 2-phenylethanol at a dilution of 10−1, Csf1r+/− mice failed to detect the odorant at any concentration. Csf2 heterozygosity restored detection to Csf1r+/− mice at a threshold of 10−2. These results indicate that the response of Csf1r+/− mice to pure odorants is impaired and that monoallelic Csf2 inactivation alleviates this phenotype. Csf2 heterozygous mice were unable to detect 2-phenylethanol but responded normally to vanilla. The basis of this selective impairment is unclear.

Figure 3. Attenuation of the Olfactory and Motor Coordination Deficits of Csf1r+/− Mice by Csf2 Heterozygosity.

(A) Odor discrimination at 7 months of age. Csf1r+/− mice showed no significant increase in exploring the pure odorant vanilla.

(B) Odor threshold to the pure odorant 2-phenylethanol by 11.5-month-old mice. Absence of a significant threshold in Csf1r+/− mice is corrected in Dhet mice.

(C) Locomotor coordination in mice, assessed as number of slips in the balance beam test.

(D) Ataxia score in mice, assessed as sum of the ledge, hindlimb, and gait scores.

Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s (A) and Dunnett’s (B) post hoc tests or by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc tests (C and D). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Inactivation of a Single Csf2 Allele Partially Improves the Motor Coordination Deficits of Female Csf1r+/− Mice

Balance beam studies have shown that older Csf1r+/− mice possess motor deficits (Chitu et al., 2015). This phenotype was reproduced with female Csf1r+/− mice. In contrast, Dhet mice were indistinguishable from the WT (p = 0.99) (Figure 3C). Similar to their behavior in the balance beam test, female but not male Csf1r+/− mice had increased ataxia scores (Guyenet et al., 2010; Figure 3D) that were not attenuated by Csf2 heterozygosity. Furthermore, Csf2 heterozygosity alone produced an ataxic phenotype. Overall, these results show that Csf1r+/− mice have a female-specific motor deficit and that targeting Csf2 improves motor coordination on the balance beam but fails to improve ataxic behavior.

Csf2 Heterozygosity Prevents Cerebral but Not Cerebellar Microgliosis of Csf1r+/− Mice

Examination of the effects of inactivation of a single Csf2 allele in 18-month-old symptomatic Csf1r+/− mice revealed that Csf2 heterozygosity prevented the increase in Iba-1+ cells in all gray and white matter tracts examined, with the exception of the cerebellum (Figures 4A and 4B). A remarkable feature was the presence of periventricular patches of high microglial density in the callosal white matter (Figures S3A and S3B). Examination of multiple sagittal sections revealed that microglial patches were more frequently encountered in Csf1r+/− mice than in WT mice and that their frequency was normalized in Csf1r+/−; Csf2+/− Dhet mice (Figure S3B). Morphometric analysis showed that microglia in the white matter patches of Csf1r+/− mice had fewer ramified processes than those of WT mice (Figures 4C and 4D), suggestive of an activated state. The ramified morphology was restored in Dhet mice. In contrast, cortical microglia showed no significant difference in ramification compared with the WT (Figures 4C and 4E).

Figure 4. Csf2 Heterozygosity Prevents Cerebral Microgliosis in Aged ALSP Mice.

(A) Iba1+ cell densities (green) in different areas of brains of 18-month-old mice. Cb, cerebellum; CC, corpus callosum; Cb WM, cerebellar white matter; Cx, primary motor cortex; DCN, deep cerebellar nuclei; Hp, hippocampus; OB, olfactory bulb.

(B) Quantification of Iba1+ cell densities.

(C) Morphology of Iba1+ cells. The dotted line indicates the border between the CC and the adjacent gray matter.

(D and E) Quantification of microglia ramification in the white (D) and gray (E) matter regions shown in (C).

(F) Quantification of microglia and infiltrating leukocytes by flow cytometry. μG, microglia; AμG, activated microglia; BLΦ, B lymphocytes; G+μG, Ly6G+ P2ry12high microglia; Gr, Ly6G+P2ry12− granulocytes; MΦ/DC, Ly6C− macrophages/dendritic cells; Mo, Ly6C+ infiltrated monocytes; NK, natural killer cells; TCD4 and TCD8, CD4 and CD8+ T lymphocytes; Tγδ, γδ T cells. Data were obtained from 16-month-old WT (n = 4) and Csf1r+/− (n = 5) mice.

(G) Colocalization of P2ry12 (red) with Iba1+ cells (green).

(H) Quantification of P2ry12 expression in Iba1+ cells in WT and Csf1r+/− mice; 5 mice/genotype.

(I) Expression of Cx3Cr1 (GFP, green) and Ccr2 (RFP, red) reporters in 11-month-old Cx3Cr1GFP/+;Ccr2RFP/+;Csf1r+/+ (+/+) and Cx3Cr1GFP/+;Ccr2RFP/+;Csf1r+/− (+/−) mice.

(J) Quantification of mononuclear phagocytes in Cx3Cr1GFP/+;Ccr2RFP/+ reporter mice (5 mice/genotype). Significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA (B, F, H, and J) or one-way ANOVA (D and E), followed by Benjamini Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Scale bars, 100 μm, apply to all panels in the corresponding composite image. Minor irregularities in (A) images Csf2+/− Cx and Csf1r+/− CC, (G) images Csf1r+/− Hp and WT Cb, and (I) WT and Csf1r+/− Cb images arise from automated image stitching in Photoshop.

See also Figures S3 and S4 and Table S9.

Absence of Leukocytic Infiltration in the Brains of Csf1r+/− Mice

Overexpression of Csf2 in peripheral helper T cells has been reported to promote monocytic infiltration in the brain (Spath et al., 2017), which could contribute to expansion of Iba1+ cells (Greter et al., 2015). To address the contribution of peripheral monocytes, we performed an unbiased flow cytometry analysis of all CD45+ cells in the brains of 15-month-old mice (Figure 4F; Figure S4). This revealed that, in WT and Csf1r+/− mice, most Ly6G– CD45+ cells were CD11b+ CD45low P2ry12high, a profile that identifies brain-resident microglia (Greter et al., 2015; Butovsky et al., 2014). Consistent with this, nearly 100% of Iba1+ cells expressed P2ry12 in all brain regions tested (Figures 4G and 4H). Analysis of the leukocyte populations revealed that Csf1r+/− mice did not exhibit increased CD45high CD11b+ P2ry12− Ly6- Clow macrophages/dendritic cells or evidence of increased infiltration of P2ry12− Ly6G+ granulocytes, CD45high CD11b+ P2ry12− Ly6Chi monocytes, or various lymphocyte populations compared with WT mice (Figure 4F). The presence of an unusual population of Ly6G+ P2ry12high cells that presumably represent an activated state of microglia (G+μG; Figure 4F; Figure S4) was also detected in aged mice of both genotypes (p = 0.73 versus the WT). Furthermore, in Cx3Cr1GFP/+; Ccr2RFP/+ mononuclear phagocyte reporter mice (Mizutani et al., 2012), regardless of genotype or region, the majority of brain mononuclear phagocytes were green fluorescent protein (GFP) single-positive and identified as resident microglia (Figures 4I and 4J). The proportions of red fluorescent protein (RFP) (Ccr2) single-positive monocytes and of cells expressing both monocytic (Ccr2) and microglial (P2ry12) markers in Csf1r+/− mice were comparable with the WT (Figures 4I and 4J). These data indicate that there is no increase in leukocytic infiltration in Csf1r+/− mice. Together with the data shown in Figures 1D and 1E, these results indicate that expansion of Iba1+ cells occurs by direct stimulation of resident microglial proliferation by CSF-2.

Gene Expression Changes in Csf1r+/− Microglia Suggest a Maladaptive Phenotype

To determine how reductions in Csf1r or Csf2 expression, alone or in combination, affect microglial function in aged (21-month-old) mice, we analyzed the changes in the transcriptome of cerebral Tmem119+ microglia compared to WT controls. Csf1r heterozygosity led to differential expression of 496 genes, comprising 237 upregulated genes (URGs) and 259 downregulated genes (DRGs) (Table S2; Figure 5A). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that a significant proportion of the Csf1r+/− URGs encoded membrane (57), extracellular (39), and mitochondrial (16) proteins (Table S3). In contrast, the innate immunity cluster contained only four URGs (Tgtp1, Ly86, and the complement proteins C1qb and C1qc). Among the URGs encoding extracellular proteins were transcripts for the secreted inducer of senescence Augurin (Ecrg4) (Kujuro et al., 2010), the neuropeptide Tac2 (Andero et al., 2016), and the CSF-2-induced proinflammatory chemokine Ccl17 (Achuthan et al., 2016; Figure 5B). Other upregulated transcripts included those encoding several mitotoxic (Apoo, Mrps6, Nr2f2, and Coq7) (Turkieh et al., 2014; Sultan et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2015; Lapointe and Hekimi, 2008) and neurodegeneration-related (Syngr1, Cst7, Trem2, Spp1, and Ch25h) (Hegyi, 2017; Ma et al., 2011; Krasemann et al., 2017; Shin et al., 2011) protein products (Figures 5B, 5F, and 5H). Interestingly, Csf1r heterozygosity did not reduce the expression of known neurotrophic factors by microglia; rather, it enhanced the expression of genes encoding neurturin, neudesin, midkine, IGF2, and vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGFB) (Figure 5B; Table S4), suggesting that microglial neurotrophic functions were not impaired.

Figure 5. Csf2 Heterozygosity Restores the Csf1r+/− Microglial Transcriptomics Profile.

(A) Differences in gene expression profile in Csf1r+/−, Csf2+/−, and Dhet microglia compared with WT controls.

(B) Volcano plot highlighting DEGs of interest in Csf1r+/− microglia.

(C) Validation of changes in expression of selected upregulated (top panel) and downregulated (lower panel) genes in microglia isolated from 4 WT, 5 Csf1r+/−, 5 Dhet, and 4 Csf2+/− mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test.

(D) Expression of Cystatin F in the CC of WT, single heterozygous, and Dhet mice. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels. N = 5 mice/genotype, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; n.s., not significant (p = 0.33).

(E and F) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)-generated list of pathways (E) and biological processes (F) affected by Csf1r heterozygosity and their predicted activation status in Csf2+/− and Dhet microglia. Dots indicate no significant difference.

(G) Heatmap showing the expression of Csf1r+/− DEGs across individual samples.

(H) Illustration of the overlap of Csf1r+/− DEGs with genes differentially expressed in other mouse models of neurodegenerative disease. Note decreased Csf1r expression in a model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (APPswe/PS1dEp) and in disease-associated microglia (DAMs-AD, DAMs-ALS). The Csf1r targeting strategy (Dai et al., 2002) does not affect transcription, precluding confident detection of decreased Csf1r expression in Csf1r+/− microglia using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (log2FC = −1.15, p = 0.01, adjusted p = 0.1).

Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Analysis of the DRGs showed that approximately 50% (132 of 259) of these encode membrane proteins (Table S3), including proteins with anti-inflammatory activity, such as Thbd, Dpep2, Pirb, Cd244, Il4ra, and Il10ra (Wolter et al., 2016; Habib et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005; Georgoudaki et al., 2015; Mori et al., 2016; Lobo-Silva et al., 2016; Figures 5B and 5F). Consistent with downregulation of interleukin-10 (IL-10) receptor signaling in Csf1r+/− microglia, its downstream signaling mediator Stat3 and several IL-10 transcriptional targets (Ddit4, Nfil3, and Tsc22d3) (Ip et al., 2017; Lang et al., 2002; Berrebi et al., 2003; Hoppstädter et al., 2015) were also downregulated (Figures 5B and 5F).

Other potentially relevant downregulated genes encode transcripts associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Sorl1) (Nicolas et al., 2016), leukodystrophy (Abcd1 and its downstream mediator of pathology, Ch25h) (Gong et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2016), and the CSF-2 target gene Pkch, encoding protein kinase Cη, a regulator of lipid metabolism and suppressor of nitrous oxide (NO) production by macrophages (Torisu et al., 2016; Ozawa et al., 2016; Figure 5B).

Pathway analysis revealed that the transcriptomic changes associated with Csf1r heterozygosity are consistent with activation of the Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor (RhoGDI) signaling and liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor (LXR/RXR) pathways (Figure 5E; Table S5). The LXR/RXR pathway has been reported to increase cholesterol efflux and repress Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-induced genes (Hiebl et al., 2018) but also promote inflammasome activation in microglia (Jang et al., 2016). However, inhibition of classical pro-inflammatory pathways, such as the acute phase response and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling, as well as of TREM1 signaling, which sustains inflammation (Owens et al., 2017), was also predicted (Figure 5E; Table S5), suggesting that Csf1r+/− microglia are not pro-inflammatory. Analysis of the biological processes affected by Csf1r heterozygosity predicted active neurodegeneration, increased cellular protrusions and microtubule dynamics, as well as elevated paired-pulse facilitation of synapses (Figure 5F; Table S6).)

To further explore how these transcriptomic changes are relevant to the neuropathology, we intersected our gene list with publicly available datasets showing changes in the microglial transcriptome in other mouse models of neurodegenerative disease, including models of Alzheimer’s disease (presenilin/amyloid precursor protein [PS-APP], AD 5xFAD, APPswe/PS1dE9), tauopathy (Tau_P301S), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), rapid neurodegeneration (CK-p25), and spinocerebellar ataxia (Mfp2−/−) (Friedman et al., 2018; Keren-Shaul et al., 2017; Mathys et al., 2017; Figure 5H). A list showing genes similarly regulated and their functions is provided in Table S7. The comparison shows that 29% of the Csf1r+/− DEGs were similarly regulated in at least one other neurodegenerative disease, with the most extensive overlap occurring with the APPswe/PS1dE9 Alzheimer’s disease model, followed by changes related to early neurodegeneration (CK-p25 early cluster 7) and ALS. Consistent with this overlap, Csf1r expression was downregulated in microglia isolated from mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and ALS (Figure 5H). Changes occurring under most neurodegenerative conditions were high expression of a group of transcripts encoding the lysososmal cathepsin inhibitor Cystatin F (Cst7) (Ma et al., 2011); osteopontin (Spp1), an opsonin for cell debris (Shin et al., 2011); and cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (Ch25h), which, through its product 25-hydroxycholesterol, activates the LXR pathway and promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and inflammation (Jang et al., 2016). Underexpression of neuroprotective (Clec4a1 and Il16; Flytzani et al., 2013; Shrestha et al., 2014) and anti-inflammatory (Klf2, Gramd4, Ddit4, Pirb, and Tsc22d3; Roberts et al., 2017; Ip et al., 2017; Kimura et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2005; Berrebi et al., 2003) transcripts was observed in ALSP and at least three other conditions (Figure 5H).

Together, our data suggest that Csf1r heterozygosity does not produce a neurotrophic defect or overt inflammatory activation of microglia. Rather, the transcriptional profile predicts a maladaptive microglial phenotype (Figure 6A). A summary of the pathways that could contribute to disease pathology is presented in Figure 6B.

Figure 6. Pathways Dysregulated in Csf1r+/− Mice and ALSP Patients.

(A and B) Predicted maladaptive functions (A) and hypothetical pathways (B) dysregulated in Csf1r+/− mouse microglia.

(C) Evidence of oxidative stress: colocalization of the poly (ADP-ribose) signal with callosal microglial patches in periventricular white matter. Scale bar, 100 μm, applies to all panels.

(D) Quantification of the callosal area positive for poly (ADP-Ribose) in 2–3 sections/mouse, 5–9 mice/genotype. One-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal-Wallis test.

(E) Transcriptomics changes potentially critical for pathology also occur in the periventricular white matter of ALSP patients (n = 5); *p < 0.05, one- tailed Student’s t test.

Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Csf2 Heterozygosity Upregulates Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Signaling in Microglia

As described above, Csf2 insufficiency alone also impaired cognition (Figure 2) and partially affected olfaction and motor coordination (Figure 3). However, these phenotypes were not accompanied by microgliosis in Csf2+/− mice. Thus, we examined the effect of Csf2 heterozygosity on microglia. Compared with WT controls, Csf2 heterozygosity dysregulated the expression of 1,168 genes (372 URGs and 796 DRGs; Figure 5A; Table S1). Most of the top differentially expressed transcripts encode products still uncharacterized or pseudogene transcripts (Figure S5A). Among the top upregulated transcripts were those encoding the proinflammatory cytokine CCL3 and the matrix metalloproteinase MMP11. The myelin-degrading MMP12 (Hansmann et al., 2012) was also upregulated (Figure S5D). Like Csf1r+/− microglia, Csf2+/− microglia downregulated the expression of several anti-inflammatory genes (Figures S5A and S5D). Remarkably, Csf2+/− microglia reduced the expression of Il4ra but not of Il10ra (Figure S5D; Tables S2 and S8).

Analysis of pathways uniquely affected by Csf2 heterozygosity showed activation of the antioxidant vitamin C pathway; of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling, which regulates lipid metabolism and is anti-inflammatory (Wahli and Michalik, 2012); and of the complement system, which has a well-established role in synapse loss in neurodegenerative disease (Hajishengallis et al., 2017; Stephan et al., 2012). Among the top predictions for inhibited pathways, we found dendritic cell maturation, neuroinflammation, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) signaling (Figure S5B). Analysis of biological processes selectively affected by Csf2 heterozygosity predicted increased inflammation and encephalitis, which were paradoxically associated with decreased leukocyte infiltration as well as decreased activation of neuroglia and microglia (Figure S5C). These data suggest that the neuropathology in Csf2+/− mice is not associated with classically defined inflammatory activation (i.e., increased proinflammatory cytokine and iNOS expression). CSF-2 insufficiency increases activation of the complement system and expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), both of which could affect neuronal network structure and function. However, it also causes activation of antioxidant (vitamin C antioxidant pathway, upregulation of Prdx4) and lipid metabolic (PPAR signaling) pathways that are expected to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation.

Targeting Csf2 in ALSP Mice Attenuates Microglial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress

Investigation of the effect of reduction of CSF-2 availability revealed a large decrease in microglial transcriptomic changes of Csf1r+/−;Csf2+/− microglia (254 DEGs, 54 URGs, and 200 DRGs) compared with Csf1r+/− microglia (Figure 5A). Indeed, hierarchical clustering of samples based on DEGs grouped Csf1r+/− and Csf2+/− apart from the Dhet samples, which were more related to WT samples (Figure 5G). Consistent with this, pathway analysis predicted restoration of RhoGDI and LXR/RXR signaling and attenuation of the neurodegenerative phenotype (Figures 5E and 5F). Furthermore, 86% of the transcriptional changes common to ALSP and other neurodegenerative conditions were eliminated in Csf1r+/−;Csf2+/− microglia (Figure 5H), including the expression of gene products that suppress mitochondrial fitness and enhance oxidative stress (e.g., Ch25h, Ddit4, Il10ra, Apoo, and Coq7). Consistent with this, monoallelic inactivation of Csf2 in Csf1+/− mice reduced poly ADP-ribosylation, a marker of oxidative stress, in periventricular white matter microglial patches (Figures 6C and 6D).

The Cst7-encoded protein Cystatin F is a microglial marker of ongoing demyelination with concurrent remyelination (Ma et al., 2011). As predicted by the changes in Cst7 transcript abundance, Cystatin F protein was readily detected in the callosal microglial patches present in Csf1r+/− brains, but its staining in Dhet brains was not significantly different from WT staining (Figure 5D). Thus, targeting CSF-2 improves microglial homeostatic functions.

Increased Expression of CSF-2 Target Genes Potentially Relevant to Pathology in the White Matter of ALSP Patients

To determine whether similar gene expression changes occur in ALSP patients, we isolated RNA from the callosal white matter of ALSP patients and control (Table S1) brains and performed real-time qPCR. Several transcripts potentially relevant to neurodegeneration, demyelination, and oxidative stress were also upregulated in the white matter of ALSP patients (Figure 6E). These results identify putative common contributors to the pathology of ALSP and of other demyelinating and neurodegenerative diseases.

Monoallelic Csf2 Inactivation on the ALSP Background Improves Callosal Myelination

Reduction of expression of the demyelination marker Cystatin F by targeting Csf2 prompted us to examine the ultrastructure of the corpora callosa of all genotypes by transmission electron microscopy. Examination of cross-sections showed that Csf1r+/− fibers have higher G-ratios than WT fibers, indicative of demyelination followed by remyelination (Figures 7A–7C). Higher G-ratios were also observed in Csf2+/− samples (Figures 7A, 7B, and 7E). The G-ratios of callosal fibers in Dhet mice were not significantly different from those of WT fibers (Figures 7A, 7B, and 7D). Consistent with this, staining for myelin basic protein (MBP) was reduced in the corpus callosum of Csf1r+/− mice and the reduction was prevented by targeting Csf2 (Figure 7F). Other white matter tracts (fimbria and cerebellar white matter), although trending similarly, were not significantly affected (Figure 7F). Changes in myelination did not result from decreased availability of platelet derived growth factor receptor-α+ (PDGFRα+) early oligodendrocyte precursors or of mature CC1+ oligodendrocytes, which were paradoxically increased (Figure 7G). Examination of age-related changes in myelin compaction revealed significantly increased myelin degeneration in Csf1r+/− mice that was not rescued by Csf2 heterozygosity (Figure 7H). In terms of axonal pathology, the data reflect a lack of protective effects of Csf2 targeting on neurodegeneration (Figure 7I). Consistent with the overall lack of protection against neurodegeneration, Csf2 heterozygosity did not attenuate the loss of neuronal nuclei+ (NeuN+) mature neurons in cortical layer V (Figures 7J and 7K). Together, these data indicate that Csf2 heterozygosity rescues myelination but is not sufficient to prevent neurodegeneration and exacerbation of age-related myelin degeneration in ALSP mice.

Figure 7. Csf2 Heterozygosity in ALSP Mice Prevents Callosal Atrophy and Improves Myelination.

(A) Myelin and axonal ultrastructure in callosal cross-sections from 9- to 11-month-old mice. Arrows point to examples of changes in myelin thickness in axons of small and medium diameters.

(B–E) Changes in G-ratio in Csf1r+/− (B and C) and Csf2+/− (B and E) mice are attenuated by double heterozygosity (B and D). (B) shows average values per mouse (2–6 mice/genotype); values in the bars indicate the total numbers of fibers examined in each fiber diameter range. (C)–(E) show individual G-ratio values.

(F) Quantification of MBP staining in white matter tracts, including CC, fimbria (Fb), and Cb. n = 3–7 mice/genotype.

(G) Changes in myelination are not accompanied by a decrease in early oligodendrocyte precursors (PDGFRα+) or oligodendrocytes (CC1+).

(H) Quantification of age-induced myelin pathology in WT and mutant mice (2–7 mice/genotype, >900 neurons/genotype). The top panels show representative examples of structural abnormalities.

(I) Quantification of age-induced axonal pathology in WT and mutant mice (data from 3–6 mice/genotype, >900 neurons/genotype). The top panels show representative examples of structural abnormalities.

(J) Neuronal loss in cortical layer V at 18 months of age. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(K) Average NeuN-positive cells per layer. n = 4 mice/genotype.

(L) Csf2 heterozygosity prevents callosal atrophy in 19-month-old Csf1r+/− mice.

Significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak’s (B, F, and K) or Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli’s (H and I) post hoc tests and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (H and L). Scale bars, 1 μm (A), 50 μm (F), 100 μm (G and J), and 500 nm (H and I); apply to all images in the corresponding panels. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

See also Table S9.

Csf2 Heterozygosity Normalizes the Callosal Volume in Csf1r +/− Mice

Because Csf2 heterozygosity in the ALSP background normalized the G-ratios, we examined whether this resulted in attenuation of white matter loss using MRI. Compared with the WT, callosal volumes were lower in Csf1r+/− mice, and Csf2 heterozygosity prevented callosal atrophy (Figure 7L). In contrast, Csf2 heterozygosity did not cause a reduction in callosal volume.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study (Chitu et al., 2015), we showed that microglial densities were elevated in several brain regions of young and old Csf1r+/− ALSP mice and associated with increased expression of Csf2, encoding the microglial mitogen CSF-2. Aside from its mitogenic activity, CSF-2 primes neurotoxic (Fischer et al., 1993) and demyelinating (Smith, 1993) responses in microglia. Because CSF2 expression is also elevated in post-mortem ALSP brains (Figure 1F), we reasoned that CSF-2 plays an important role in ALSP pathogenesis. Indeed, we show that Csf2 heterozygosity rescues the olfactory, cognitive, and depression-like phenotypes of Csf1r+/− mice and ameliorates the motor coordination deficits (Figures 2 and 3). Csf2 targeting also reduces microgliosis (Figures 1A, 1B, 4A, and 4B) and a hallmark feature of ALSP, demyelination (Figures 7A–7D and 7F). Although, in the CNS, the CSF-2 receptor is expressed on neural lineage cells (Reed et al., 2005; Baldwin et al., 1993) and microglia, several lines of evidence suggest that Csf2 deletion ameliorates neuropathology by acting on microglia rather than on neural lineage cells. First, the reported neuroprotective (Schäbitz et al., 2008) and oligodendrogenic (Baldwin et al., 1993) activities of CSF-2 suggest that its targeting in ALSP should be detrimental rather than protective. However, we found that Csf2 heterozygosity did not exacerbate loss of layer V neurons, indicating that its neuroprotective actions are negligible in the context of ALSP. Furthermore, in the ALSP mouse, demyelination is paradoxically associated with an expansion of oligodendrocyte precursors and APC+ oligodendrocytes (Figure 7G). Targeting of Csf2 prevents the increase in oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursors in ALSP mice (Figure 7G), but this finding cannot explain how it attenuates the loss of myelin. One conceivable explanation is that Csf2 heterozygosity prevents microgliosis (Lee et al., 1994) and priming of demyelinating (Smith, 1993) and neurotoxic (Fischer et al., 1993) responses in microglia. A direct investigation of the contribution of CSF-2 signaling in different cell types to pathology requires conditional targeting of its receptor, Csf2ra, which is presently not possible because of the absence of a specific genetic model. An acceptable approximation is conditional targeting of Csf2rb, which encodes the common subunit of CSF-2, IL-3, and IL-5 receptors (Croxford et al., 2015), using lineage-specific Cre drivers. Using this approach, we showed that attenuation of CSF-2 signaling in CX3CR1-expressing cells (i.e., mononuclear phagocytes and microglia) was sufficient to prevent white matter microgliosis in young mice (Figures 1D and 1E). Based on this observation and on the finding that monocyte-derived cells do not significantly contribute to the widespread microgliosis in aged Csf1r+/− mice (Figures 4F–4J), we conclude that CSF-2 triggers microgliosis via direct signaling in CNS-resident microglia. Thus, although a contribution of CSF-2 signaling in other cell types cannot be formally excluded, current data suggest that the CSF-2-mediated dysregulation of microglial function plays a central role in the pathology of ALSP mice. Consistent with this, transcriptomic analysis revealed that Csf2 heterozygosity suppressed a high proportion of the transcriptomic changes occurring in Csf1r+/− microglia, including the expression markers of oxidative stress and demyelination (Figures 5 and 6 and a more detailed discussion below).

Transcriptomics analysis suggests that clearance of apoptotic cells and myelin debris triggers maladaptive responses in Csf1r+/− microglia. Relevant changes include overexpression of TREM2, an innate immune receptor expressed on microglia that promotes clearance of apoptotic neurons and myelin debris (Poliani et al., 2015). Recent work indicates that, following uptake of apoptotic neurons or neuronal debris, TREM2 increases the expression of oxidative stress markers and complement components and suppresses the homeostatic function of microglia (Linnartz-Gerlach et al., 2019; Krasemann et al., 2017). The molecular mechanism could involve suppression of mitophagy either directly (Ulland et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019) or as an indirect consequence of overloading of the degradative pathway by the ingested myelin (Safaiyan et al., 2016). Furthermore, as observed in the mouse model (Figure 5C), overexpression of TREM2 also occurs in the white matter of ALSP patients (Figure 6E), where others have documented the presence of lipid-laden macrophages (Tada et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2010). Thus, decreased autophagy may contribute to ALSP pathology, and the benefits of stimulation of autophagy should be further explored.

Dysregulation of lipid metabolism may also contribute to ALSP. One of the genes downregulated in Csf1r+/− microglia encodes the very-long-chain fatty acid transporter ABCD1. Mutations in ABCD1 cause X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, a demyelinating disease associated with microglial dysfunction mediated by overexpression of Ch25h encoding cholesterol 25 hydroxylase (Gong et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2016). The product of cholesterol 25 hydroxylase (CH25H), 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC), is an activating ligand of LXR, providing an explanation for activation of the LXR/RXR pathway in Csf1r+/− microglia (Figure 5E). In vivo, 25-HC has been reported to promote oligodendrocyte death, and in vitro, 25-HC stimulates IL-1β secretion by microglia in a mitochondrial ROS- and LXR/RXR-dependent manner (Jang et al., 2016). Expression of CH25H was also elevated in the white matter of ALSP patients (Figure 6E), suggesting that dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism in microglia may contribute to the pathology of ALSP.

Double Csf1r and Csf2 heterozygosity eliminates the changes in most canonical pathways and biological processes produced by either Csf1r or Csf2 heterozygosity alone (Figures 5E and 5F; Figures S5B and S5C), including activation of the LXR/RXR pathway (Figure 5E). In the context of ALSP, Csf2 heterozygosity virtually restores microglial function, resulting in attenuation of oxidative stress, improvement of callosal myelin thickness, and restoration of callosal volume (Figures 5, 6, and 7). Together with normalization of most behavioral phenotypes of Csf1r+/− mice by monoallelic targeting of Csf2, these studies clearly identify CSF-2 as a therapeutic target in ALSP. In addition, this work demonstrates that reduction of either CSF-1R or CSF-2 signaling impairs microglia function and homeostasis of the aging CNS and that rebalancing the signals is beneficial. Increased CSF2 levels and decreased microglial Csf1r expression have been reported in Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 5; Tarkowski et al., 2001) and multiple sclerosis (Kostic et al., 2018; Werner et al., 2002). Thus, apart from ALSP, the unbalanced CSF-1R/CSF-2 signaling described here may contribute to the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative conditions.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Dr. E. Richard Stanley (richard.stanley@einsteinmed.org). The study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

In vivo animal studies

Mouse Strains, Breeding and Maintenance

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health regulations on the care and use of experimental animals and approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The generation, maintenance and genotyping of Csf1+/− mice was described previously (Dai et al., 2002). Csf2+/− mice (Dranoff et al., 1994) were a gift from Dr. Glenn Dranoff and were genotyped using a PCR procedure developed by the Dranoff laboratory that utilizes the primers listed in the Key Resources table. Both lines were backcrossed for more than 10 generations onto the C57BL6/J background. Cohorts were developed from the progeny of matings of Csf1r+/− to Csf2+/− mice, randomized with respect to the litter of origin. At 3 months of age, they were transferred from a breeder diet (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 5058) to a lower fat maintenance diet (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 5053). This prevented the increase in body weight in Csf1r+/− mice compared with wild-type mice observed in our earlier study (Chitu et al., 2015) and was also associated with delayed onset of spatial memory deficits (from 7 to 14 months of age) and absence of motor impairment in male Csf1r+/− mice. Csf2rbfl/fl mice (Croxford et al., 2015) were provided by Dr. Burkhard Becher, via Dr. William R Drobyski, Medical College of Wisconsin, Cx3Cr1GFP/+; Ccr2RFP/+ mononuclear phagocyte reporter mice (Saederup et al., 2010) were a gift from Dr. Susanna Rosi, Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience, University of California, San Francisco and Cx3Cr1Cre/+ mice (Yona et al., 2013) were a gift from Dr. Marco Prinz, Institute of Neuropathology, Freiburg University Medical Centre, Freiburg, Germany. The age and sex of animals used in each experiment is indicated in Table S9.

Human studies

Frozen brain tissue blocks containing periventricular white matter were obtained from the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank. Consent for autopsy was obtained from the legal next-of-kin. Studies involving autopsy tissue are exempt from human subjects research (Health and Human Services Regulation 45 CFR Part 46). Information on the ALSP patients harboring CSF1R mutations and control cases included in this study is summarized in Table S1. Upon removal from the skull according to standard autopsy pathology practices, the brain was divided in the mid-sagittal plane. Half was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and half was frozen in a −80°C freezer, face down to avoid distortion. The frozen brain was shipped on dry ice to the Neuropathology Laboratory at Mayo Clinic where it was stored in −80°C freezer. Frozen tissue was partially thawed before dissection and slabbed in a coronal plane at about 1-cm thickness. Regions of interest were dissected from the frozen slabs and placed in microcentrifuge tubes before being shipped to the research laboratory on dry ice. At all steps, the fresh and frozen tissue was handled with Universal Precautions.

METHOD DETAILS

Cognitive Assessment

Behavioral studies were carried out by blinded operators. Recognition memory was assessed as time exploring a familiar and a novel object, using the novel object recognition test (Ennaceur and Delacour, 1988). The experimental groups were first tested at 7 months of age for short-term memory (1h-retention interval), then at the age of 16 months for long-term memory (24h-retention interval). Mice explored two identical objects (familiarization) for 4 min (1h-retention) or for 10 min (24h-retention) during the training stage. Mice were then exposed to one of the familiar objects and to a novel object for 3 min (1h-retention) or 5 min (24h-retention) during the testing stage. Each mouse was placed in the center of a 40 cm x 40 cm open field box and allowed to explore the objects freely during each stage. Two different pairs of non-toxic objects were used for each experiment. The novelty of the objects (i.e., novel versus familiar) was counter-balanced within each genotype and the objects were previously validated for equivalent exploratory valence.

Spatial recognition memory was measured at 13.5 months of age in the two-trial test version of the Y-maze (Biundo et al., 2016). Briefly, during the training trial, one of the arms of the maze was closed, and mice were placed into one of the two remaining arms of the maze (start arm) and allowed to explore the open two arms for 10 min. After a 1h inter-trial interval, the blocked arm was opened (novel arm), and mice were placed in the start arm and allowed to explore freely all three arms of the maze for 5 min (test trial).

Spatial recognition memory was also tested at 14.5 months of age in the object placement test (Ennaceur and Delacour, 1988). Each mouse was exposed for 7 min to two identical objects placed in a 40 cm x 40 cm open field box. Four different visual cues were hung on the walls of the box to permit each mouse to orient within the arena. During the training stage, the objects were placed at a distance of 10 cm from one another. After an interval of 25 minutes, one of the objects was displaced into a novel position (15 cm distance, 90 degree angle) and each mouse was returned to the same box to explore the objects for 5 min (testing).

Olfactory Assessment

Olfactory discrimination was tested at 8 months of age. Each mouse was exposed to two non-social odors, a pure odorant attractant (vanilla extract) and an aversive odorant (lime extract), and to water as control. Each odorant was adsorbed in a filter paper placed in a 30-mm Petri dish (5 ul of lime extract, 30 ul of vanilla extract, or 30 ul of water per filter). During the test, a single mouse was placed in the center of a 40 cm x 40 cm box in which the dishes containing odorant filters were placed in two opposite corners of the box, while two dishes containing water-adsorbed-filters were placed in the remaining opposite corners. All the dishes were covered until each mouse was placed in the box. Mice were allowed to explore for 10 minutes. Time exploring each odorant and water was recorded during two 5-minute consecutive bins.

The ability of mice to explore a pure odorant was further assessed in 10-month-old mice using the olfactory threshold test in which exploration of the pure odorant, 2-phenylethanol, or mineral oil carrier, applied to a cotton tip, is assessed (Doty et al., 1978; Witt et al., 2009). All experiments were carried in a plexiglas box placed in a odor-free ventilated hood. Before testing, each mouse was habituated to the cotton tip by being exposed five times to mineral oil. During the testing trials, the experimental groups were exposed to 5 ten-fold serial dilutions (from 10−4 to 10°) of the odorant. Between each dilution of odorant mice were exposed to mineral oil. In each condition, the cumulative time spent exploring the odorant or mineral oil over a 1 minute period was recorded.

Depression-like Behavior

Depression-like behavior was assessed as immobility, using the Porsolt Forced Swim Test (Porsolt et al., 1977a; Porsolt et al., 1977b). Briefly, each mouse was placed into a 4-l beaker filled with warm water (24°C) for 10 minutes and the duration of immobility during three, 3-minute, consecutive bins was recorded.

Motor Coordination and Ataxic Behavior

Motor coordination was assessed as the number of slips made while crossing a round, wooden balance beam (Gulinello et al., 2008). Briefly, each mouse was allowed to walk along a 1.6 cm diameter, 1 m long beam placed between two holders 1 m off the ground. Palatable food was placed at the end of the beam as an incentive to cross. The ataxia phenotype was evaluated as the sum of scores in the ledge, the hindlimb clasping and the gait tests, as previously described (Guyenet et al., 2010).

Gene Expression Studies in ALSP Patients

RNA was isolated from either the periventricular white matter or the adjacent gray matter of 5 ALSP patients and 5 control patients (see Table S1) using Trizol and cDNA was prepared using a Super Script III First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real time PCR was performed using SYBR Green in an Eppendorf Realplex II thermocycler. The primers used are listed in Table S10. Average values from two different blocks of tissue per patient, were used to construct the figures.

Analysis of Microglia and Leukocytes

Microglia and brain leukocytes were analyzed using and adaptation of the protocol described by Legroux et al. (2015). Briefly, mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS containing 10 U/ml heparin. Brains were dissected, minced and digested in 5 mL digestion buffer (2mg/ml Collagenase D, 14 μg/ml DNase I in Hanks’ Balanced Salt solution (HBSS)) for 20’at 37°C. Myelin was removed by centrifugation in 37% Percoll in HBSS for 10 minutes at 500 × g, without brakes. The cell pellet was washed twice with FACS buffer (2% FCS in PBS), and the Fc receptors were blocked by incubation in FACS buffer containing rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Fc block) for 15 minutes on ice. The cells were stained using the antibodies diluted 1:200 in FACS buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C in the dark. Cells were subsequently washed twice with FACS buffer, resuspended in 1ml FACS buffer containing 2.5 μg/ml DNase I and analyzed in a MoFlo Astrios EQ (Beckman Coulter, IN). The antibodies used for staining are listed in the Key Resources Table and the gating strategy utilized to identify each cell type is shown in Figure S3. Data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10.6.1.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Mouse BD Fc Block) | BD | Cat#533142; RRID: AB_394657 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 APC-Cy7 (clone 30-F11) | BD | Cat#557659; RRID: AB_396774 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G BV605 (clone 1A8) | BioLegend | Cat# 127639, RRID:AB_2565880 |

| Anti-mouse /human CD11b BV510 (clone M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat#101263; RRID: AB_2629529 |

| Anti-mouse P2RY12 PE (clone S16007) | BioLegend | Cat#848004, RRID:AB_2721645 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c APC (clone N418) | BioLegend | Cat# 117309, RRID:AB_313778 |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6C BV711 (clone HK1.4) | BioLegend | Cat# 128037, RRID:AB_2562630 |

| Anti-mouse CD19 Alexa 700 (clone 6D5) | BioLegend | Cat# 115527, RRID:AB_493734 |

| Anti-mouse NK-1.1 BV785 (clone PK136) | BioLegend | Cat# 108749, RRID:AB_2564304 |

| Anti-mouse CD3 PE/Cy7 (clone 17A2) | BioLegend | Cat# 100219, RRID:AB_1732068 |

| Anti-mouse TCRγδ BV421 (clone GL3) | BioLegend | Cat# 118119, RRID:AB_10896753 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 PerCP-eFluor 710 (clone GK1.5) | Invitrogen | Cat# 44-0041-82; RRID:AB_11150050 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a FITC (clone 53-6.7) | BioLegend | Cat# 100705, RRID:AB_312744 |

| Anti-Iba1, Rabbit | Wako | Cat# 019-19741, RRID:AB_839504 |

| Anti-Iba1, Goat | AbCam | Cat# ab107159, RRID:AB_10972670 |

| Anti-P2RY12, Rat | Dr. O. Butovsky | Gift |

| Anti-MBP (Smi99), Mouse | BioLegend | Cat# 808401, RRID:AB_2564741 |

| Anti-APC (CC1), Mouse | Millipore | Cat# OP80, RRID:AB_2057371 |

| Anti-PDGFRα, Goat | R and D Systems | Cat# AF1062, RRID:AB_2236897 |

| Anti-CST7, Rabbit | Bioss | Cat# bs-6039R, RRID:AB_11073757 |

| Anti-Poly ADP-ribose (Clone H10), Mouse | Millipore | Cat# MABC547, RRID:N/A |

| Anti-NeuN, Mouse | BioLegend | Cat# MAB377X, RRID:AB_2149209 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human brain tissue samples | Mayo Clinic, FL | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57/BL6 CSF-1R knockout mouse | Dai et al., 2002 | N/A |

| C57/BL6 Csf2+/− mice | Dranoff et al., 1994 | N/A |

| C57/BL6 Csf2rbfl/fl mice | Croxford et al., 2015 | N/A |

| C57/BL6 Cx3Cr1Cre/+ mice | Yona et al., 2013 | N/A |

| C57/BL6 Cx3Cr1GFP; Ccr2RFP reporter mouse | Saederup et al., 2010 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Fluoromyelin | Invitrogen | Cat# F34652 |

| DAPI | Biolegend | Cat# 422801 |

| Triton X-100 | EMS | Cat# 22140 |

| Tween 20 | Sigma | Cat# P9416 |

| Percoll | VWR | Cat# 17-0891-01 |

| Myelin Removal Beads II | Milteny Biotec | Cat# 130-096-733 |

| RNAsin | Promega | Cat# N2615 |

| DNaseI, RNase-free | Thermo Scientific | Cat#EN0525 |

| TRIzol | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 15596018 |

| FCS | Atlanta Biologicals | Cat# S12450H |

| Donkey serum | Millipore | Cat# 566-460 |

| Collagenase D | Roche Diagnostic | Cat# 11088866001 |

| DNase I | Roche Diagnostic | Cat# 11284932001 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Live/Dead Fixable Far Red Dead Cell Stain Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# L34973 |

| RNEasy Plus Micro RNA Extraction Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 74034 |

| ProLong Gold Antifade with DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat# P36935 |

| Mouse GM-CSF Quantikine ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# MGM00 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Human CSF2 PrimePCR Assay | BIO-RAD | Cat# 10025636 qHsaCED0002766 |

| Csf2+/− mice genotyping forward wt: TCGTCTCTAACGAGTTCTCCTTCA | Dranoff et al., 1994 | N/A |

| Csf2+/− mice genotyping reverse wt: TGCTCGAATATCTTCAGG | Dranoff et al., 1994 | N/A |

| Csf2+/− mice genotyping reverse Csf2 KO: GGCCACTTGTGTAGCGCCAAGT | Dranoff et al., 1994 | N/A |

| Primers for qPCR | See Table S10 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Schindelin et al., 2012 | http://fiji.sc/ |

| Microglia morphometry algorithm | Young and Morrison, 2018 | http://www.jove.com/video/57648/quantifying-microglia-morphology-from-photomicrographs |

| Other | ||

| Collection of electron micrographs illustrating the effects of aging in the brain | (Peters and Folger Sethares) | http://www.bu.edu/agingbrain |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw FACS data for Figure 4H | Mendeley Data | https://doi.org/10.17632/7m928vkpht.1 |

| RNA Seq data | GEO | Accesion number GSE143823 |

Microglia Isolation and RNA-Seq Analysis

Microglia were isolated by FACS (Bennett et al., 2016). The RNA was extracted using a QIAGEN RNeasy Plus Micro kit and stored at −80°C prior to analysis. We obtained 150 bp paired-end RNA-Seq reads from an Illumina NextSeq 500 instrument. For 3 biological replicates of wild-type, Csf1r+/−, Csf2+/−, and 2 biological replicates for Csf1r+/−;Csf2+/− samples, an average of ~46 million pairs of reads per sample was obtained. The computational pipeline for identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) has been described previously (Wang et al., 2017). Briefly, adapters and low quality bases in reads were trimmed by trim_galore: (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). The Kallisto (v0.43.1) software (Bray et al., 2016) was employed to determine the read count and transcripts per kilobase million (TPM) for each gene that was annotated in the GENCODE database (vM15) (Mudge and Harrow, 2015). Then we summed the read counts and TPM of all alternative spliced transcripts of a gene to obtain gene expression levels. To identify DEGs, 14,739 expressed genes with an average TPM > 1 were selected in any of the wild-type, Csf1r+/−, Csf2+/− and Csf1r+/−;Csf2+/− samples, using the software DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. For selected genes changes in expression were validated by qPCR, utilizing the primers listed in Table S10. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) (https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/) was used for canonical pathway analysis.

Comparison of DEGs With Other Datasets

The DEG lists from Csf1r+/− or Csf2+/− samples were compared to the DEG lists generated from other studies of microglia transcriptome changes associated with neurodegeneration (Mathys et al., 2017; Keren-Shaul et al., 2017). In Keren-Shaul et al. (2017) and Friedman et al. (2018), DEGs were defined as FDR < 0.05, as described in the original papers, while in Mathys et al. (2017) DEGs were defined by |z| > 2. The log2(fold-change) of those DEGs were used to generate heatmaps.

MRI Imaging

Mice were imaged on an Agilent Direct Drive 9.4 T MRI system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described (Chitu et al., 2015). Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in room air, and respiratory rate and oxygenation saturation were monitored and maintained within normal ranges, while body temperature was maintained at 39°C, using a warm air circulator (SA instruments, Bayshore, NY). A 1.8mm actively decoupled surface coil (Doty Scientific, Columbia, SC) was used for acquisition, and a 60 mm ID birdcage volume coil (M2M Imaging, Cleveland, OH) was used for radio frequency transmission. Callosal volumes were measured using MIPAV 7.1.1 freeware (https://mipav.cit.nih.gov/).

Ultrastructural Studies

Callosal sections were obtained as described (Chitu et al., 2015). Briefly, mice were perfused with 30 mL of cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 U heparin/ml followed by 30 mL of 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The dissected brains were cut into 2 mm thick slices and placed in cacodylate fixation buffer (2% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) for 40 min at room temperature. Corpus callosum was dissected, incubated overnight at 4°C in cacodylate fixation buffer, embedded, sectioned, stained and examined by transmission electron microscopy using a FEI Technai 20 transmission electron microscope. The ratio between the diameter of an axon and the mean diameter of the myelinated fiber (G-ratio) was determined on 200 randomly chosen fibers (3–6 animals/ genotype) using ImageJ software (imagej.net). Age-related ultrastructural changes were identified according to the description provided by Peters and Sethares (Alan Peters and Claire Folger Sethares, The fine structure of the aging brain (http://www.bu.edu/agingbrain)) and quantified in 15 different microscopic fields /mouse (3–6 animals/genotype; average neurons/genotype 1118; range 929–1498).

Immunofluorescence Staining of Brain Sections

Brain sections (30 μm thick) were obtained as described (Chitu et al., 2015) and stained using antibodies to ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) (rabbit IgG; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA or goat IgG; AbCam, Cambridge, MA), cystatin F (rabbit IgG; Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), poly(ADP-ribose) (mouse monoclonal, Millipore, Billerica, MA), myelin basic protein (mouse monoclonal, BioLegend, Dedham, MA), PDGFRa (goat polyclonal, Minneapolis, MN), CC1 (a mouse antibody to APC reacting with Quaking 7, Millipore, Danvers, MA) and NeuN (mouse monoclonal, Millipore, Danvers, MA). Rat anti-P2ry12 was a gift from Dr. Oleg Butovsky (Harvard Medical School). Secondary antibodies, conjugated to either Alexa 488, Alexa 594 or Alexa 647, were from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Images were captured using an Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope with NISElements D4.10.01 software. Quantification of cell numbers was performed manually. Quantification of fluorescent areas was performed using ImageJ. Images were cropped and adjusted for brightness, contrast and color balance using Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Microglia morphometry

Brain sections (30 μm thick) were obtained and stained with Iba1 as described in the previous section. Z series stacks were acquired using a Leica SP5 Confocal microscope at 40x magnification with a 2 μm interval between images. Morphometric analysis of microglia was carried out in FIJI on maxiumum intensity projections of tissue sections from 3 mice/genotype using the protocol described by Young and Morrison (2018).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were screened for the presence of outliers using the ROUT method, assessed for Gaussian distribution by D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test and analyzed using Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test or two-way ANOVA, as appropriate. Pairwise differences were identified using post hoc multiple comparison tests. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Data within each group are presented as averages ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Only those differences that have reached statistical significance are indicated on the figures. Sample sizes for each experiment are indicated in the figure legends and more information can be found in Table S9.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Data Availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplemental materials. The source data for Figure 4F are available in the Mendeley Database: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/7m928vkpht/draft?a=19e92205–6537-4f8b-9278-f2399d5a55ba. RNA Seq data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database: GSE143823.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

ALSP is a CSF1R-deficiency dementia associated with increased CSF2 expression

In Csf1r+/−ALSP mice, CSF-2 promotes microgliosis by direct signaling in microglia

Targeting Csf2 improves cognition and myelination and normalizes microglial function

CSF-2 is a therapeutic target in ALSP

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ian Willis of the Department of Biochemistry for critically evaluating the manuscript; Dr. Shahina B. Maqbool of the Epigenomics Shared Facility for RNA-seq; Leslie Cummins and Frank Macaluso of the Analytical Imaging Facility for preparation of transmission EM samples; Drs. Craig A. Branch and Min-Hui Cui of the Gruss Magnetic Resonance Research Center for MRI imaging; Hillary Guzik, Andrea Briceno, and Dr. Vera DesMarais of the Analytical Imaging Facility for help with imaging and histomorphometry; and Drs. Fabien Delahaye and Xusheng Zhang of the Computational Genomics Core Facility for data analysis (all at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine). This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01NS091519 to E.R.S., NS071571 to M.F.M., and U54 HD090260 [support for the Rose F. Kennedy IDDRC]), the P30CA013330 NCI Cancer Center grant, and grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_146130 and 316030_150768 to B.B. and PP00P3 144781).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPORTING CITATIONS

The following references appear in the Supplemental Information: Jiang et al. (2014); Li et al. (2010); Liu et al. (2018); Moriguchi et al. (2016); Rydbirk et al. (2016); Stock et al. (2016); Tian et al. (2017); Xiang et al. (2015); Zeisel et al. (2013).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.028.

REFERENCES

- Achuthan A, Cook AD, Lee MC, Saleh R, Khiew HW, Chang MW, Louis C, Fleetwood AJ, Lacey DC, Christensen AD, et al. (2016). Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces CCL17 production via IRF4 to mediate inflammation. J. Clin. Invest 126, 3453–3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andero R, Daniel S, Guo JD, Bruner RC, Seth S, Marvar PJ, Rainnie D, and Ressler KJ (2016). Amygdala-Dependent Molecular Mechanisms of the Tac2 Pathway in Fear Learning. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 2714–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin GC, Benveniste EN, Chung GY, Gasson JC, and Golde DW (1993). Identification and characterization of a high-affinity granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor on primary rat oligodendrocytes. Blood 82, 3279–3282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ML, Bennett FC, Liddelow SA, Ajami B, Zamanian JL, Fernhoff NB, Mulinyawe SB, Bohlen CJ, Adil A, Tucker A, et al. (2016). New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E1738–E1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi D, Bruscoli S, Cohen N, Foussat A, Migliorati G, Bouchet-Delbos L, Maillot MC, Portier A, Couderc J, Galanaud P, et al. (2003). Synthesis of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) by macrophages: an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mechanism shared by glucocorticoids and IL-10. Blood 101, 729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biundo F, Ishiwari K, Del Prete D, and D’Adamio L (2016). Deletion of the γ-secretase subunits Aph1B/C impairs memory and worsens the deficits of knock-in mice modeling the Alzheimer-like familial Danish dementia. Oncotarget 7, 11923–11944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, and Pachter L (2016). Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, Koeglsperger T, Dake B, Wu PM, Doykan CE, et al. (2014). Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci 17, 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Gokhan S, Gulinello M, Branch CA, Patil M, Basu R, Stoddart C, Mehler MF, and Stanley ER (2015). Phenotypic characterization of a Csf1r haploinsufficient mouse model of adult-onset leukodystrophy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP). Neurobiol. Dis 74, 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Gokhan Sx., Nandi S, Mehler MF, and Stanley ER (2016). Emerging Roles for CSF-1 Receptor and its Ligands in the Nervous System. Trends Neurosci. 39, 378–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford AL, Lanzinger M, Hartmann FJ, Schreiner B, Mair F, Pelczar P, Clausen BE, Jung S, Greter M, and Becher B (2015). The Cytokine GM-CSF Drives the Inflammatory Signature of CCR2+ Monocytes and Licenses Autoimmunity. Immunity 43, 502–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, Sylvestre V, and Stanley ER (2002). Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Brugger WE, Jurs PC, Orndorff MA, Snyder PJ, and Lowry LD (1978). Intranasal trigeminal stimulation from odorous volatiles: psychometric responses from anosmic and normal humans. Physiol. Behav 20, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranoff G, Crawford AD, Sadelain M, Ream B, Rashid A, Bronson RT, Dickersin GR, Bachurski CJ, Mark EL, Whitsett JA, et al. (1994). Involvement of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in pulmonary homeostasis. Science 264, 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, and Delacour J (1988). A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res 31, 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer HG, Bielinsky AK, Nitzgen B, Däubener W, and Hadding U (1993). Functional dichotomy of mouse microglia developed in vitro: differential effects of macrophage and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on cytokine secretion and antitoxoplasmic activity. J. Neuroimmunol 45, 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flytzani S, Stridh P, Guerreiro-Cacais AO, Marta M, Hedreul MT, Jagodic M, and Olsson T (2013). Anti-MOG antibodies are under polygenic regulation with the most significant control coming from the C-type lectin-like gene locus. Genes Immun. 14, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman BA, Srinivasan K, Ayalon G, Meilandt WJ, Lin H, Huntley MA, Cao Y, Lee SH, Haddick PCG, Ngu H, et al. (2018). Diverse Brain Myeloid Expression Profiles Reveal Distinct Microglial Activation States and Aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease Not Evident in Mouse Models. Cell Rep. 22, 832–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoudaki AM, Khodabandeh S, Puiac S, Persson CM, Larsson MK, Lind M, Hammarfjord O, Nabatti TH, Wallin RP, Yrlid U, et al. (2015). CD244 is expressed on dendritic cells and regulates their functions. Immunol. Cell Biol 93, 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann T, Wieghofer P, Müller PF, Wolf Y, Varol D, Yona S, Brendecke SM, Kierdorf K, Staszewski O, Datta M, et al. (2013). A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1618–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Sasidharan N, Laheji F, Frosch M, Musolino P, Tanzi R, Kim DY, Biffi A, El Khoury J, and Eichler F (2017). Microglial dysfunction as a key pathological change in adrenomyeloneuropathy. Ann. Neurol 82, 813–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greter M, Lelios I, and Croxford AL (2015). Microglia Versus Myeloid Cell Nomenclature during Brain Inflammation. Front. Immunol 6, 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulinello M, Chen F, and Dobrenis K (2008). Early deficits in motor coordination and cognitive dysfunction in a mouse model of the neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder, Sandhoff disease. Behav. Brain Res 193, 315–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet SJ, Furrer SA, Damian VM, Baughan TD, La Spada AR, and Garden GA (2010). A simple composite phenotype scoring system for evaluating mouse models of cerebellar ataxia. J. Vis. Exp (39), 1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib GM, Shi ZZ, Cuevas AA, and Lieberman MW (2003). Identification of two additional members of the membrane-bound dipeptidase family. FASEB J. 17, 1313–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemeyer N, Hanft KM, Akriditou MA, Unger N, Park ES, Stanley ER, Staszewski O, Dimou L, and Prinz M (2017). Microglia contribute to normal myelinogenesis and to oligodendrocyte progenitor maintenance during adulthood. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 441–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Reis ES, Mastellos DC, Ricklin D, and Lambris JD (2017). Novel mechanisms and functions of complement. Nat. Immunol 18, 1288–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann F, Herder V, Kalkuhl A, Haist V, Zhang N, Schaudien D, Deschl U, Baumgärtner W, and Ulrich R (2012). Matrix metalloproteinase-12 deficiency ameliorates the clinical course and demyelination in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol 124, 127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi H (2017). Connecting myelin-related and synaptic dysfunction in schizophrenia with SNP-rich gene expression hubs. Sci. Rep 7, 45494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebl V, Ladurner A, Latkolik S, and Dirsch VM (2018). Natural products as modulators of the nuclear receptors and metabolic sensors LXR, FXR and RXR. Biotechnol. Adv 36, 1657–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppstädter J, Kessler SM, Bruscoli S, Huwer H, Riccardi C, and Kiemer AK (2015). Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper: a critical factor in macrophage endotoxin tolerance. J. Immunol 194, 6057–6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip WKE, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, and Medzhitov R (2017). Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 356, 513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Park S, Jin Hur H, Cho HJ, Hwang I, Pyo Kang Y, Im I, Lee H, Lee E, Yang W, et al. (2016). 25-hydroxycholesterol contributes to cerebral inflammation of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Commun 7, 13129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Tan MS, Gu LZ, Zhang YD, and Tan L (2014). Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 knockdown exacerbates aging-related neuroinflammation and cognitive deficiency in senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1243–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, David E, Baruch K, Lara-Astaiso D, Toth B, et al. (2017). A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 169, 1276–1290.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Endo S, Inui M, Saitoh S, Miyake K, and Takai T (2015). Endoplasmic Protein Nogo-B (RTN4-B) Interacts with GRAMD4 and Regulates TLR9-Mediated Innate Immune Responses. J. Immunol 194, 5426–5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T, Tada M, Tada M, Koyama A, Nozaki H, Harigaya Y, Nishimiya J, Matsunaga A, Yoshikura N, Ishihara K, et al. (2014). Haploinsufficiency of CSF-1R and clinicopathologic characterization in patients with HDLS. Neurology 82, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T, Kasanuki K, Ikeuchi T, Dickson DW, and Wszolek ZK (2018). CSF1R-related leukoencephalopathy: A major player in primary microgliopathies. Neurology 91, 1092–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic M, Zivkovic N, Cvetanovic A, and Stojanovic I (2018). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as a mediator of autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol 323, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, Beckers L, O’Loughlin E, Xu Y, Fanek Z, et al. (2017). The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujuro Y, Suzuki N, and Kondo T (2010). Esophageal cancer-related gene 4 is a secreted inducer of cell senescence expressed by aged CNS precursor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8259–8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, and Murray PJ (2002). Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J. Immunol 169, 2253–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, and Hekimi S (2008). Early mitochondrial dysfunction in long-lived Mclk1+/− mice. J. Biol. Chem 283, 26217–26227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Liu W, Brosnan CF, and Dickson DW (1994). GM-CSF promotes proliferation of human fetal and adult microglia in primary cultures. Glia 12, 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legroux L, Pittet CL, Beauseigle D, Deblois G, Prat A, and Arbour N (2015). An optimized method to process mouse CNS to simultaneously analyze neural cells and leukocytes by flow cytometry. J. Neurosci. Methods 247, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu X, Zhang B, Qi D, Zhang L, Jin Y, and Yang H (2010). Overexpression of candidate tumor suppressor ECRG4 inhibits glioma proliferation and invasion. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res 29, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WL, Wszolek ZK, and Dickson DW (2010). Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids: ultrastructural and immunoelectron microscopic studies. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol 3, 665–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnartz-Gerlach B, Bodea LG, Klaus C, Ginolhac A, Halder R, Sinkkonen L, Walter J, Colonna M, and Neumann H (2019). TREM2 triggers microglial density and age-related neuronal loss. Glia 67, 539–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wei Z, Ma X, Yang X, Chen Y, Sun L, Ma C, Miao QR, Hajjar DP, Han J, and Duan Y (2018). 25-Hydroxycholesterol activates the expression of cholesterol 25-hydroxylase in an LXR-dependent mechanism. J. Lipid Res 59, 439–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo-Silva D, Carriche GM, Castro AG, Roque S, and Saraiva M (2016). Balancing the immune response in the brain: IL-10 and its regulation. J. Neuroinflammation 13, 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]