Summary

Plant biodiversity is a source of potential natural products for the treatment of many diseases. One of the ways of discovering new drugs is through the cytotoxic screening of extract libraries. The present study evaluated 196 extracts prepared by maceration of Brazilian Atlantic Forest trees with organic solvents and distilled water for cytotoxic and antimetastatic activity. The MTT assay was used to screen the extract activity in MCF‐7, HepG2 and B16F10 cancer cells. The highest cytotoxic extract had antimetastatic activity, as determined in in vitro assays and melanoma murine model. The organic extract of the leaves of Athenaea velutina (EAv) significantly inhibited migration, adhesion, invasion and cell colony formation in B16F10 cells. The phenolic compounds and flavonoids in EAv were identified for the first time, using flow injection with electrospray negative ionization‐ion trap tandem mass spectrometry analysis (FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MSn). EAv markedly suppressed the development of pulmonary melanomas following the intravenous injection of melanoma cells to C57BL/6 mice. Stereological analysis of the spleen cross‐sections showed enlargement of the red pulp area after EAv treatment, which indicated the activation of the haematopoietic system. The treatment of melanoma‐bearing mice with EAv did not result in liver damage. In conclusion, these findings suggest that A velutina is a source of natural products with potent antimetastatic activity.

Keywords: antimetastatic potential, Athenaea velutina, Brazilian Atlantic Forest, cytotoxic activity, phenolic compounds, plant extract screening

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, biodiversity and its chemical constituents have played crucial roles in new drug discoveries. 1 Indeed, there is a growing interest in investigating natural products as sources of new drugs. 2 Despite the fact that pharmaceutical companies mainly focus on libraries of synthetic substances, nonetheless natural products can have more drug‐like chemical space than synthetic compounds this may allow better interaction with macromolecules involved in the genesis of different forms of pathologies. 3

The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to scientists who discovered the natural products, ivermectin and artemisinin. In both cases the strategy adopted included a massive screening of extract libraries, consisting of partially purified fractions and pure compounds isolated from microorganisms and plants. 4 The US National Institute of Cancer (NCI‐Frederick) maintains the largest and most diverse library of extracts in the world. 5 The screening of natural product libraries led to the development of important anticancer drugs initially isolated from Taxus brevifolia bark, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel taxanes. 6 , 7 The screening methodology, standardized by NCI, is a model used by other research groups worldwide. 8 , 9

Developing countries need to ensure sustainable exploitation of their natural resources to generate wealth through commercial products such as food, medicines and cosmetics. 10 The Brazilian Atlantic Forest is well known for its wide biological diversity and important ecosystem services. It is also a threatened area owing to the high levels of deforestation and fragmentation. 11 Nevertheless, this forest is still part of the Brazilian biome, and has great potential for bioprospecting; this hotspot houses approximately 20 000 plant species with a high percentage of endemism. 12 Although this tropical forest mass originally covered 17% of the Brazilian territory, it is now reduced to a small fragment, with an irreplaceable loss of species. 13

The future of bioprospecting for natural products relies on the preservation of biodiversity, maintenance of a legal guarantee of access to genetic heritage, and accuracy of scientific data on the taxonomic information and localization of organism sources using a Global Positioning System (GPS). 14 , 15 , 16 In addition, the introduction of policies that stimulate the development of new phytomedicines is essential. In Brazil, a few compounds isolated from natural sources have resulted in the generation of patents or encouraged the formulation of new drug leads. 17 , 18

Given this background, this study aimed to screen plant extracts and identify potential new sources of anticancer natural products from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Our preliminary results reported the cytotoxicity of the organic extract from leaves of Athenaea velutina (EAv). Therefore, further experiments were designed to evaluate the potential antimetastatic activity of EAv in melanoma B16F10 cells to determine its toxicological effects and to perform the first phytochemical investigation of A. velutina.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant materials and preparation of extracts

Access to the plant material was authorized by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/number 010134/2014‐0) and was performed using a random strategy in semi‐deciduous forest that had a high proportion of endemic species. 19 Forty‐nine tree species were taxonomically identified from vegetative and reproductive organs, and their voucher specimens were deposited in the VIC Herbarium of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Identification was performed with the aid of specialized bibliography, consultation with specialists, and comparison with herborized material from the VIC Herbarium by specialists. The species names and botanical families were checked against the database of the list of species from Brazilian Flora 2020 Project. 20 The trees were georeferenced by GPS and identified by labelling plates in accordance with the taxonomic family, genus and species. Extracts were obtained by the maceration method using the methodology proposed by McCloud, 5 with some modifications. Plant samples (eg leaves and stems) were cut into small pieces and dried in a plant dehydrator (40°C) for various times duration, depending on the nature of the plant part. The dried material was then ground using a hammer mill. The powdered plant material was sequentially extracted with an organic solvent mixture (dichloromethane/methanol, 1:1) and distilled water. The extraction time for each step was 15 hours. The organic solvent was completely removed at 40°C under reduced pressure, and the aqueous extract was concentrated by freeze‐drying. All extracts were stored at low temperature (−20°C) in glass bottles prior to screening.

2.2. Ethical approval

All procedures performed with the animals were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles in animal research approved by the Ethics Committee of Animal Use of UFV (protocol number: 515/2016).

2.3. FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MSn analysis

Flow injection analysis (FIA) was performed using an ion trap (IT) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific LTQ XL) equipped with the XCalibur software. For the analysis, 10 mg EAv was suspended in 1.0 mL methanol/water (85:15) using an ultrasound bath. After dilution, a 10 ppm solution was prepared and subjected to a clean‐up step by using SPE C‐18 cartridges previously conditioned with 1.5 mL methanol and 1.5 mL methanol/water (85:15). The cartridge was loaded with 1.5 mL of the sample extract, which was first washed with methanol/water (85:15), and then eluted with 1.5 mL of methanol. The sample was redissolved in methanol to a concentration of 10 ppm and was analysed in the negative mode of electrospray ionization (ESI). We used a fused‐silica capillary tube at 280°C, spray voltage of 5.00 kV, capillary voltage of −35 V, and tube lens of −100 V and a 10.0 µL/min flow. Full‐scan analysis was recorded in m/z range from 150 to 2000. Multiple‐stage fragmentations (ESI‐MSn) were performed using the collision‐induced dissociation (CID) method against helium for ion activation. The total ion current (TIC) profile was generated by monitoring the intensity of all the ions produced. The MSn experiments were performed at collision energy of 30% and an activation time of 30 ms through the acquisition of MS/MS spectra. The product ions were submitted to further fragmentation in the same conditions, until no more fragments were observed. Identification was achieved through comparison with the molecular mass and fragmentation with reference data from literature.

2.4. Cell culture

The cell lines used were human breast carcinoma (MCF‐7), murine metastatic melanoma (B16F10), human hepatocarcinoma HepG2, African green monkey kidney (Vero) and embryonic mouse fibroblast (NIH3T3). The cells, kindly provided by Anésia Aparecida Santos (Departamento de Biologia Geral, UFV), were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with foetal bovine serum (FBS; 10% v/v; LGC Biotechnology), penicillin (100 U/mL; Sigma‐Aldrich), streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Sigma‐Aldrich) and 2 µM L‐glutamine (Sigma‐Aldrich). These cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. For the assays, the cells were detached from culture flask using trypsin (0.25%).

2.5. In vitro cytotoxic screen

The cells were seeded onto 96‐well plates with cell densities appropriate for each cell line: MCF‐7 (105 cell/well), B16F10 (104 cells/well), HepG2 (5 × 104 cells/well), Vero (5 × 104 cells/well) and NIH3T3 (104 cells/well). After 24 hours, the concentrated extracts were diluted in RPMI medium and evaluated at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL. The cell viability was quantified after incubation for 48 h with 5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma‐Aldrich); the resulting formazan crystals were solubilized in DMSO (Synth), and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. 21 Cell growth inhibition (GI%) was calculated in accordance with the formula GI% = [100–(T/C) × 100%], where T was the absorbance in the presence of extract and C was the absorbance of the negative control (0.25% v/v DMSO). All extracts that reduced the growth of three cancer cell lines by 60% or more were tested again at eight serial dilution concentrations, in the range from 1.562‐200 μg/mL, to determine the GI50 (the concentration of the extract that inhibits 50% of cell growth).

2.6. Wound healing mobility assay

To investigate the ability of EAv to inhibit cellular motility, a wound healing assay was performed. Initially, B16F10 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on to 6‐well plates and allowed to grow at 37°C and 5% CO2 until a confluence of approximately 80% was reached. The cell monolayer was then scratched with a sterile 200 µL pipette tip. Subsequently, the cellular debris were washed away and replaced with 3 mL of serum‐reduced medium (2% v/v) with different concentrations of EAv (1.562‐12.5 μg/mL) for 24 hours. The images were captured by using an inverted microscope (Evos FL, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 0, 6, 12 and 24 hours after EAv addition. The distances from the wound edges were measured using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), and the percentages of cell migration were calculated relative to the control. 22

2.7. Cell adhesion assay

After treatment with different concentrations of EAv (1.562‐12.5 μg/mL) for 1 hours, cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 96‐well Matrigel‐coated plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. 23 Non‐adherent cells were removed by gentle washing with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The adherent cells on the plate were measured by MTT assay, with 0.25% (v/v) DMSO‐vehicle treatment used as the control.

2.8. Cell invasion assay

Transwell chambers (8 µm pore size; Merck) were coated with Matrigel (60 μg/well) to evaluate the invasion of B16F10. 24 The cells (2 × 105 cells/well in serum‐free medium) were seeded in the upper chamber with or without EAv (1.562‐12.5 μg/mL). In the lower chamber, culture medium containing FBS (10% v/v) was added to attract the cells. After 24 hours, the cells that invaded the lower chamber were fixed and stained with methanol (20% v/v) and toluidine blue (0.5% v/v), respectively. The number of cells in each chamber was determined as average of cells counted in 10 randomly selected fields under the optical microscope (200 × magnification) and quantified using the ImageJ software, with 0.25% (v/v) DMSO‐vehicle treatment used as the control.

2.9. Colony formation assay

This assay evaluated the survival and ability of EAv‐treated cells to form colonies. 25 Briefly, B16F10 cells (1 × 103 cells/well) were plated in 6‐well plates containing RPMI with FBS (2% v/v). After 24 hours, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing EAv (1.562‐12.5 μg/mL) for 24 hours; DMSO‐vehicle treatment (0.25% v/v) was used as the control. The cells were then grown for 14 days without EAv, replacing culture medium every 3 days. At the end of the experiment, the colonies were fixed and stained with methanol (20% v/v) solution and toluidine blue (0.5% v/v), respectively. The total number of colonies was counted using the ImageJ software and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control cultures.

2.10. Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (6‐7 weeks old; body weight [bw] 16‐18 g) were provided by the Central Animal Facility of the Center of the Biological and Health Sciences of UFV. The animals were housed in polypropylene cages (n = 5) and exposed to a controlled photoperiod (12:12 hours light/dark) and temperature (21°C). Water and rodent feed were provided ad libitum.

2.11. In vivo lung colony assay

B16F10 melanoma cells (1 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 0.2 mL of culture medium, and then injected through the lateral tail vein of each C57BL/6 mice. The tumour cell‐bearing mice were weighed and divided equally into two groups (n = 5 each). EAv was solubilized in 200 μL PBS with DMSO (1% v/v) and administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 100 mg/kg bw. In the control group, the animals were administered 200 μL PBS plus DMSO (1% v/v), which simulated treatment stress and minimized the possible influence of the ingested liquid. Daily treatment with EAv started 24 h after tumour induction and was continued for 21 days. The bw of each mouse was recorded every 5 days to determine whether treatment with EAv influenced animal health. On the 22nd day, all animals were weighed, anesthetized (ketamine, 150 mg/kg [Dopalen] and xylazine, 10 mg/kg [Anasedan]) and euthanized. The liver, spleen and lungs were dissected out, weighed and fixed in paraformaldehyde (4% v/v, Synth) for further histopathological analysis. In particular, the lungs were excised in four lobes, and the black nodules were counted by two independent observers under a dissecting microscope. The relative weight of the organs was calculated according to the following formula: organ somatic index weight = organ weight (g)/body weight (g) × 100.

2.12. Histological processing and morphometry

For histological analysis, fragments of lung, spleen and liver were dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series and embedded in 2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate (Historesin; Leica Microsystems). 26 Histological sections with a thickness of 3 μm were obtained using a rotary microtome (RM 2255; Leica Biosystems) and stained with haematoxylin/eosin (H&E). Finally, the slices were qualitatively analysed using a light microscope (Olympus CX40). Digital images of melanoma and spleen were captured at 10 × magnification by a light microscope (Olympus BX‐53) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus DP73) and analysed with the ImageJ software. The percentage of the internal melanoma area relative to the total area of lung sections, as well as the relationship between the percentage areas of white and red pulp in the spleen, was analysed in 50 histological fields per group. 27 Total areas of 2.85 × 106 and 1.15 × 107 µm2 were analysed for lung and spleen, respectively.

2.13. Biochemical analysis

Blood was collected from heart puncture of melanoma B16F10‐bearing mice. The serum was separated by centrifugation at 500 g for 20 min. Biochemical parameters of liver functions (alanine amino transferase [ALT, KO49‐6] and aspartate amino transferase [AST, K048‐6]), kidney functions (creatinine [CRE, K067‐1] and urea [URE, K056‐1]) were analysed using kits donated by BioClin® in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol using the automatic analyser BS‐200 (Mindray) that was previously calibrated with standards from different quantified biochemical parameters.

2.14. Haemolysis assay

Blood from healthy C57BL/6 mice was collected by the retro‐orbital route and stored in vials with anticoagulant (acid citrate dextrose). A 450 μL sample of blood was incubated with 50 μL of EAv at concentrations ranging from 1.562 to 12.5 μg/mL for 3 hours. Thereafter, plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation (500 g for 10 min). A 50 μL sample of plasma was mixed with 450 μL Na2CO3 solution (0.01%). In 96‐well plates, 200 μL aliquots were dispensed and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Saline (0.1% NaCl) was used as a negative control, and Triton (1%) was used as a positive control (considered to represent 100% of the amount of haemoglobin released). 28 The degree of haemolysis in each sample treated with EAv was calculated as a percentage using the following formula: Haemolysis (%) = absorbance sample treated with EAv/absorbance of control × 100%.

2.15. Statistical analysis

Non‐linear regression analysis was performed to calculate the GI50 of cytotoxic activity. The statistical differences between groups were determined by a two‐tailed Student's t test or one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. All statistical tests were computed using the GraphPad Prism 6.0 statistical software (GraphPad software Inc). The results were considered significant at P < .05. All in vitro assays were performed in triplicate as three independent experiments, and the results were normalized to the control samples.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cytotoxic activity of the library of extracts in cancer cell lines

In total, 196 plant extracts were screened for their cytotoxic activity at a concentration of 100 µg/mL in three cancer cell lines using the MTT assay. These extracts were produced from the leaves and stems from the plants of 49 species in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest using solvents with different polarities. All plants were traceable by GPS and were labelled with identification plates in nature to allow other re‐extractions. Plant extracts were selected based on their ability to cause more than 60% cell growth inhibition (GI60) in B16F10, HepG2 and MCF‐7 cancer cell lines (Table 1). Therefore, organic extracts from the leaves of Casearia sylvestris Sw. (Salicaceae), Acnistus arborescens (L.) Schltdl. (Solanaceae) and Athenaea velutina (Sendtn.) D’Arcy (Solanaceae), in the concentration range from 1.562 to 200 µg/mL, were evaluated by the dose response assay. These extracts exhibited GI50 values below 10 μg/mL in minimum one tumour line (Table 2). In addition, C. sylvestris and A. velutina extracts exhibited a high selectivity index (SI) for Vero cells. The cytotoxic activity of these extracts was classified as moderate (M) in accordance with the criteria adopted by NCI. 29 Consequently, as the cytotoxic activity achieved by organic extract from leaves of A velutina (EAv) was associated with unpublished data, further assays were performed to obtain structural elucidation of the metabolites present in EAv and to investigate its antimetastatic potential in melanoma B16F10 cells.

Table 1.

Cell Growth Inhibition (GI%) of the plant extracts against cancer cells

| Family | Plant species | Voucher | Parts | GI (%) a ; Extracts b [100 µg/mL] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16F10 | HepG2 | MCF‐7 | |||||||

| OE | AE | OE | AE | OE | AE | ||||

| Anacardiaceae | Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi | VIC40.349 | Leaves | 24% | NI | NI | 15% | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Annonaceae | Annona sylvatica A.St.‐Hil. | VIC40.574 | Leaves | 69% | 55% | 27% | 23% | 35% | 37% |

| Stems | 17% | 24% | 22% | NI | 43% | NI | |||

| Annonaceae | Guatteria australis A.St.‐Hil. | VIC40.511 | Leaves | 50% | 49% | 23% | 19% | 23% | 18% |

| Stems | 72% | NI | 11% | 21% | 18% | 35% | |||

| Annonaceae | Xilopia sericea A.St.‐Hil. | VIC40.432 | Leaves | 62% | 29% | NI | NI | 15% | NI |

| Stems | 17% | NI | NI | NI | 18% | 11% | |||

| Apocynaceae | Tabernaemontana hystrix Steud. | VIC40.521 | Leaves | 56% | 45% | NI | NI | 17% | 38% |

| Stems | 92% | 27% | 75% | NI | 49% | 42% | |||

| Asteraceae | Vernonanthura discolor (Spreng.) H.Rob. | VIC40.381 | Leaves | NI | NI | 22% | 20% | 44% | 28% |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | 57% | 42% | |||

| Asteraceae | Vernonanthura polyanthes (Sprengel) Vega & Dematteis | VIC40.383 | Leaves | 77% | NI | 75% | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Bignoniaceae | Cybistax antisyphilitica (Mart.) Mart. | VIC40.528 | Leaves | NI | NI | 13% | 16% | NI | 24% |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | 32% | 29% | |||

| Cannabaceae | Trema micrantha (L.) Blume | VIC40.364 | Leaves | 33% | NI | 20% | 21% | 14% | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | 19% | 19% | NI | NI | |||

| Celastraceae | Monteverdia aquifolia (Mart.) Biral | VIC40.427 | Leaves | 31% | 30% | NI | 26% | 27% | 13% |

| Stems | 48% | 18% | 24% | 27% | 13% | 16% | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Alchornea glandulosa Poepp. & Endl. | VIC40.484 | Leaves | 32% | 15% | NI | NI | 15% | 31% |

| Stems | NI | 13% | NI | 22% | 34% | 40% | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Aparisthmium cordatum (A.Juss.) Baill. | VIC40.483 | Leaves | NI | NI | 30% | NI | NI | 72% |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | 30% | 57% | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton celtidifolius Baill. | VIC40.568 | Leaves | 37% | NI | NI | 21% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 75% | 12% | 25% | 20% | 17% | NI | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Joannesia princeps Vell. | VIC40.481 | Leaves | 35% | NI | NI | NI | 33% | NI |

| Stems | NI | 14% | 23% | NI | NI | 24% | |||

| Erythroxylaceae | Erythroxylum citrifolium A.St.‐Hil. | VIC40.612 | Leaves | 58% | 19% | 22% | 24% | 32% | 28% |

| Stems | 53% | 28% | 18% | NI | NI | 24% | |||

| Fabaceae | Anadenanthera peregrina (L.) Speg. | VIC40.206 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | NI | 13% | NI |

| Stems | 10% | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Fabaceae | Bauhinia fortificata Link | VIC40.549 | Leaves | 26% | NI | 23% | 20% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 34% | NI | 25% | 29% | NI | 34% | |||

| Fabaceae | Dalbergia nigra (Vell.) Allemão ex Benth. | VIC40.498 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | 52% | NI | NI | NI | 20% | 30% | |||

| Fabaceae | Inga cylindrica(Vell.) Mart. | VIC40.209 | Leaves | 62% | 43% | 11% | NI | 13% | 23% |

| Stems | 61% | 37% | 17% | NI | 16% | NI | |||

| Fabaceae | Piptadenia gonoacantha (Mart.) JFMacbr. | VIC40.225 | Leaves | NI | 52% | NI | NI | NI | 24% |

| Stems | 47% | 15% | NI | 12% | NI | NI | |||

| Fabaceae | Senna macranthera (DC. ex Collad.) HSIrwin & Barneby | VIC40.533 | Leaves | NI | NI | 21% | 19% | 34% | 20% |

| Stems | 28% | NI | NI | NI | 40% | 30% | |||

| Lamiaceae | Aegiphilla integrifolia (Jacq.) Moldenke | VIC40.539 | Leaves | NI | 11% | 25% | 25% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 52% | 11% | 24% | 27% | 11% | 20% | |||

| Lauraceae | Endlicheria paniculata (Spreng.) JFMacbr. | VIC40.253 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | 25% | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | 13% | NI | NI | 41% | 12% | |||

| Lauraceae | Nectandra oppositifolia Nees | VIC40.227 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Malvaceae | Ceiba speciose (A.St.‐Hil.) Ravenna | VIC40.342 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | 16% | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | 21% | 23% | NI | 22% | |||

| Malvaceae | Luehea grandiflora Mart. & Zucc. | VIC40.338 | Leaves | 59% | 24% | 20% | 24% | NI | 16% |

| Stems | 58% | NI | 26% | 24% | NI | 35% | |||

| Melastomatacea | Miconia latecrenata (DC.) Naudin | VIC40.396 | Leaves | 23% | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Melastomatacea | Miconia petropolitana Cogn. | VIC40.397 | Leaves | 54% | NI | NI | NI | 30% | NI |

| Stems | 27% | 57% | 22% | 25% | 38% | 41% | |||

| Meliaceae | Trichilia pallida Sw.. | VIC40.286 | Leaves | NI | NI | 25% | 21% | 12% | 15% |

| Stems | NI | NI | 42% | 22% | 19% | 7% | |||

| Moraceae | Clarisia ilicifolia (Spreng.) Lanj. & Rossberg | VIC40.265 | Leaves | 36% | 46% | NI | 11% | 31% | NI |

| Stems | 43% | 18% | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Moraceae | Ficus eximia Schott | VIC40.263 | Leaves | NI | NI | 21% | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Moraceae | Maclura tinctoria (L.) D.Don ex Steud. | VIC40.267 | Leaves | 82% | NI | 44% | NI | 42% | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia florida DC. | VIC40.304 | Leaves | NI | NI | 18% | 19% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 66 | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Myrtaceae | Marlierea teuscheriana (O.Berg) D.Legrand | VIC40.300 | Leaves | 40% | 54% | 40% | 35% | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | 13% | 26% | 19% | NI | NI | |||

| Myrtaceae | Myrciaria glazioviana (Kiaersk.) GMBarroso ex Sobral | VIC40.310 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | 62% | 52% | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium jambos (L.) Alston | VIC40.312 | Leaves | 58% | 75% | NI | 11% | 14% | NI |

| Stems | 63% | 17% | NI | NI | 13% | 32% | |||

| Nyctaginaceae | Guapira opposita (Vell.) Reitz | VIC40.277 | Leaves | 26% | 23% | 25% | 23% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 54% | 20% | NI | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Phytolaccacea | Seguieria langsdorffii Moq. | VIC40.410 | Leaves | NI | NI | 24% | 33% | 33% | 21% |

| Stems | 34% | 34% | 18% | 17% | 11% | 13% | |||

| Primulaceae | Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R.Br ex Roem. & Schult. | VIC40.421 | Leaves | NI | NI | 26% | 27% | NI | NI |

| Stems | 37% | NI | 21% | 18% | NI | 38% | |||

| Rubiaceae | Bathysa nicholsonii K.Schum. | VIC40.638 | Leaves | NI | NI | 28% | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | 20% | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Rubiaceae | Psychotria vellosiana Benth. | VIC40.282 | Leaves | 23% | 32% | 21% | NI | 43% | 38% |

| Stems | 20% | NI | NI | NI | 39% | 46% | |||

| Salicaceae | Casearia decandra Jacq. | VIC40.392 | Leaves | NI | 37% | 19% | NI | 18% | 39% |

| Stems | NI | NI | 22% | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Salicaceae | Casearia sylvestris Sw. | VIC40.390 | Leaves | 85% | 81% | 85% | 80% | 62% | 54% |

| Stems | 34% | NI | 30% | NI | NI | NI | |||

| Sapindaceae | Allophylus racemosus Sw. | VIC40.331 | Leaves | NI | NI | 21% | NI | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | 12% | NI | 24% | 36% | 17% | |||

| Siparunaceae | Siparuna guianensis Aubl. | VIC40.408 | Leaves | NI | NI | NI | 15% | NI | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | 39% | 17% | NI | NI | |||

| Solanaceae | Acnistus arborescens (L.) Schltdl. | VIC40.327 | Leaves | 91% | 35% | 76% | 18% | 75% | 34% |

| Stems | 26% | 20% | 18% | 20% | NI | NI | |||

| Solanaceae | Athenaea velutina (Sendtn.) D’Arcy | VIC40.313 | Leaves | 84% | 44% | 75% | 25% | 68% | 27% |

| Stems | 77% | 22% | 75% | 21% | 48% | NI | |||

| Solanaceae | Solanum cernuum Vell. | VIC40.323 | Leaves | 30% | 30% | NI | NI | 31% | 38% |

| Stems | 38% | 26% | NI | 12% | 30% | 28% | |||

| Verbenaceae | Aloysia virgata (Ruiz & Pav.) Juss. | VIC40.582 | Leaves | NI | NI | 17% | NI | 40% | NI |

| Stems | NI | NI | NI | NI | 33% | NI | |||

Cell growth inhibition (GI%) was obtained from the formula GI% = [100‐(T/C) × 100%], where T was the absorbance in the presence of the extract and C was the absorbance of the control (0.25% DMSO). NI = no inhibition. B16F10 (murine melanoma), HepG2 (human hepatocarcinoma) and MCF‐7 (human breast carcinoma).

OE: organic extracts; AE: aqueous extracts. Plant materials were processed and extracted as described in the materials and methods section.

Bold values represent cell growth inhibition more than 60% (GI60).

Table 2.

In vitro cytotoxic activity and selectivity index of plant extracts selected by prescreening

| Plant extracts a | Cell lines (GI50 µg/mL) b | SI c | Mean log GI50 d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16F10 | HepG2 | MCF‐7 | Vero | |||

| Casearia sylvestris | 3.81 ± 0.97 | 12.60 ± 6.03 | 26.34 ± 3.56 | 48.51 ± 2.10 | 12 | 1.03 M |

| Acnistus arborescens | 13.34 ± 7.69 | 5.01 ± 0.73 | 18.75 ± 3.34 | 45.35 ± 5.97 | 3 | 1.03 M |

| Athenaea velutina | 6.22 ± 2.92 | 17.34 ± 4.47 | 18.45 ± 6.07 | 75.20 ± 18.24 | 12 | 1.09 M |

Organic extract (1:1 mixture of dichloromethane and methanol) from leaves.

Cytotoxic activity expressed as GI50 values determined by the MTT assay. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Cell lines: B16F10 (murine melanoma), HepG2 (human hepatocarcinoma), MCF‐7 (human breast carcinoma) and Vero (African green monkey kidney).

Selectivity index (SI) = GI50 (Vero)/GI50 (B16F10).

Extracts were classified on basis of the NCI criteria 30 for the mean of log GI50 as I (inactive, mean > 1.5), W (weak activity, mean between 1.1 and 1.5), M (moderate activity, mean between 0 and 1.1) and P (potent activity, mean < 0).

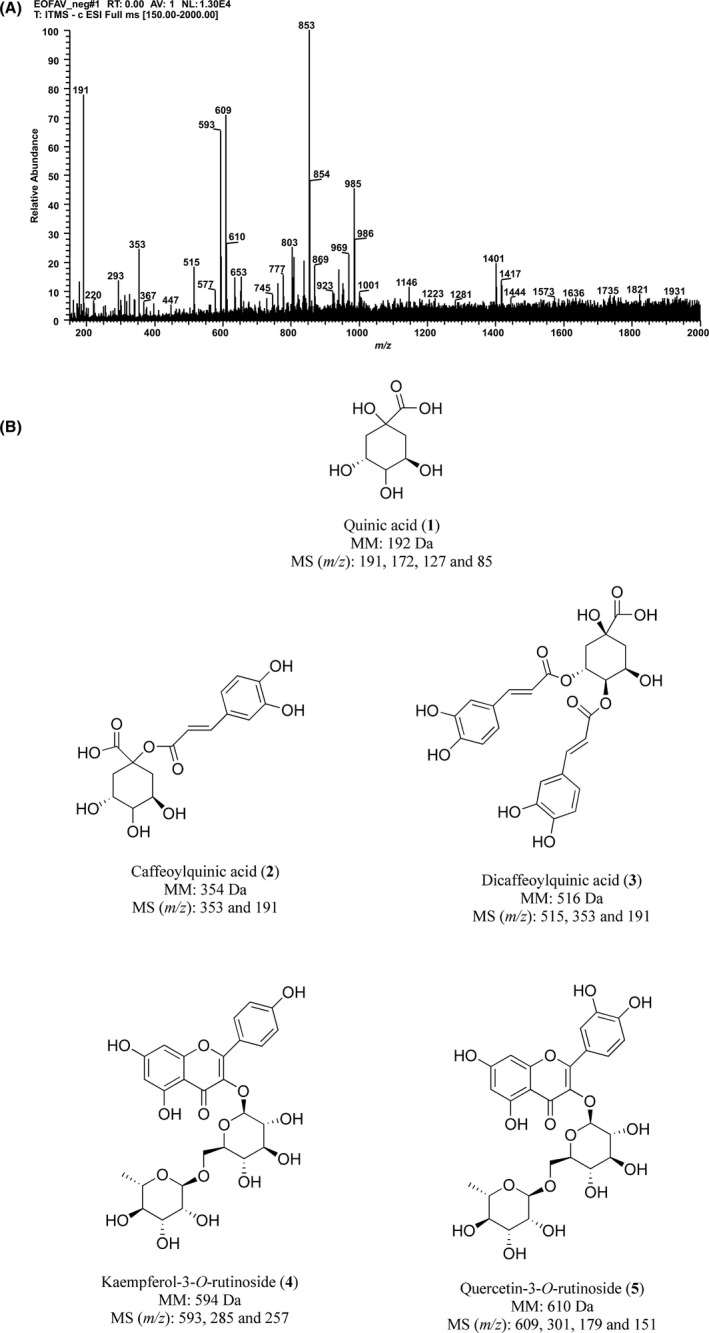

3.2. FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MSn analysis of the EAv

The information obtained from the negative mode analysis of molecular ions, and their fragmentation, when compared with data of the literature for these compounds, showed that EAv consisted predominantly of a mixture of phenolic compounds (Figure 1). Five phenolic acid compounds were identified: three simple phenolics, quinic acid (1), and its caffeic acid derivatives—caffeoylquinic acid (2) and dicaffeoylquinic acid (3); and two flavonoids, kaempferol‐3‐O‐rutinoside (4) and quercetin‐3‐O‐rutinoside (5).

Figure 1.

Phytochemical profile of A. velutinaleaves extract. (A) FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MS Spectrum obtained from the negative mode analysis. (B) Chemical structures of the proposed phenolic compounds 1‐5. MM: molecular mass. MS (m/z): precursor ion plus fragment ions identified

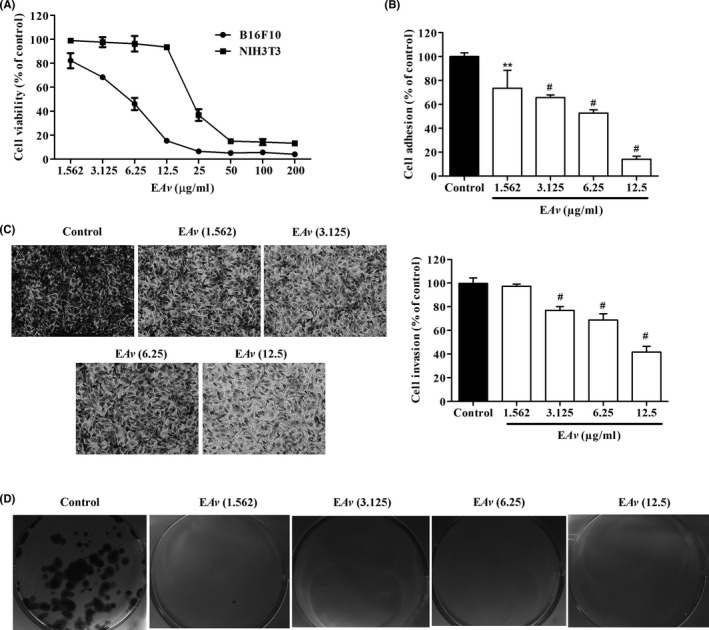

3.3. EAv inhibits adhesion, invasion and clonogenic potential of B16F10 cells

To determine the concentrations to be used for the in vitro antimetastatic assays, the cytotoxicity of EAv was evaluated in embryonic mouse fibroblasts (NIH3T3 cells). EAv did not affect the viability of NIH3T3 cells at concentrations below 12.5 µg/mL (Figure 2A). For this reason, the concentrations of 1.562, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 μg/mL were chosen for the evaluation of the antimetastatic potential of EAv in melanoma B16F10 cells. EAv significantly (P < .01) inhibited cell adhesion to Matrigel in a concentration‐dependent manner, as shown in Figure 2B. As the percentage of inhibition was expressed in comparison with untreated cells at 100%, the reduction of cell attachment after the application of 1.562, 3.125, 6.25 and 12.5 µg/mL of EAv was approximately 27%, 35%, 47% and 89%, respectively. In the invasion assay, although untreated B16F10 cells migrated freely through Matrigel induced by serum, there was a significant inhibition of migratory capability (P < .001) after treatment with EAv concentration of 3.125 μg/mL or more (Figure 2C). At 12.5 μg/mL, EAv reduced serum‐induced invasion to the lower surface of the Transwell chamber by 58.3%. In addition, EAv induced a cytostatic effect on long‐term colony formation assay in B16F10 cells. Approximately, 120 colonies were counted per well in the control cells, whereas only one colony was observed in the wells treated with EAv at 1.562 μg/mL (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Effect of EAv on cell viability, adhesion, invasion and colony formation. (A) B16F10 and NIH3T3 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of EAv for 48 hours. The cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. (B) Spectrophotometric quantification of the percentage of adhesion of B16F10 cells to Matrigel. (C) B16F10 cells treated with EAv were incubated in transwell chambers for 24 hours. Representative images (200 × magnification) of cells that invaded chamber lower surface stained with toluidine blue. (D) Representative images of the colony formation assay in which the cells were stained with toluidine blue. In the adhesion, invasion and colony formation assays, EAv was evaluated at non‐cytotoxic concentrations for NIH3T3. The results (mean ± SD) were expressed as a percentage of the negative control. Statistical differences in relation to control untreated cells were obtained by one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test (**P < .01; #P < .001)

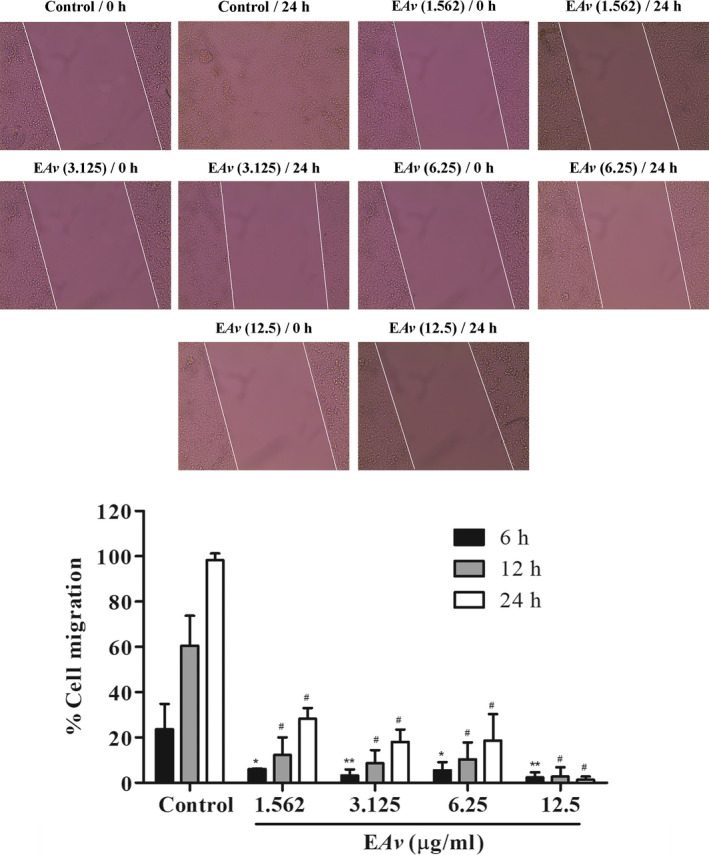

3.4. EAv suppresses in vitro migration in time‐ and dose‐dependent manners

The wound healing assay was used to determine the antimigratory potential of EAv at non‐cytotoxic concentrations. Hence, cell migration was effectively (P < .05) inhibited after treatment with EAv in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner compared with the control cells (Figure 3). B16F10 cells, treated with the vehicle DMSO (0.25% v/v), migrated along the edges of the wound and repaired the wound quickly, resulting in 60% healing after incubation with EAv for 12 hours. After incubation for 24 hours, the presence of the slit was not observed, and complete cell confluency was attained. Meanwhile, at the end of the experiment, EAv significantly inhibited the percentage of B16F10 cell migration at 71.8% and 82% at the non‐cytotoxic concentrations of 1.562 and 3.125 μg/mL, respectively, compared to that observed following control treatment.

Figure 3.

EAv suppresses migration of B16F10 cells in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner. Melanoma B16F10 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of EAv at non‐cytotoxic concentrations. The wound width was measured, and the percentage of cell migration was expressed as the mean ± SD from the difference in width of the analysed times in relation to 0 hours. Representative images were taken after incubation (magnification of 100×). One‐way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test (*P < .05; **P < .01; #P < .001)

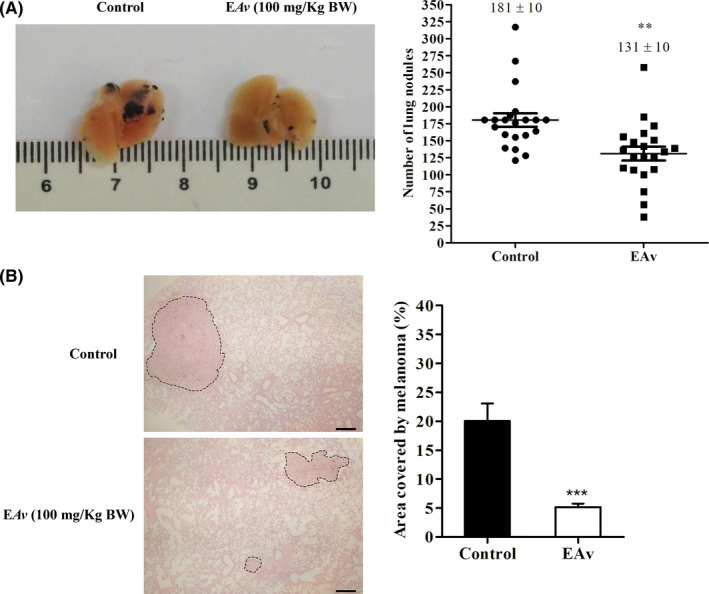

3.5. EAv inhibits melanoma development in C57BL/6 mice

The ability of EAv to suppress the spread of melanoma in vivo was tested in a lung colonization assay after the injection of melanoma B16F10 cells in C57BL/6 mice via the tail vein. Treatment with EAv (100 mg/kg bw) was performed each day for 21 days after tumour cell inoculation. The number of surface black nodules was significantly lower (P < .01) in the lungs of EAv‐treated animals (131 ± 10) than in untreated animals (181 ± 10), as shown in Figure 4A. After the morphometric analysis of lung tissue, the potential antimetastatic activity of leaves extract from A. velutina was confirmed. The area occupied by internal melanoma was fourfold lower after EAv treatment (Figure 4B). In the lung parenchyma of control mice, the internal melanocytic area was 20%, whereas this value markedly decreased to 5.1% in EAv‐treated animals (P < .001). Overall, EAv treatment significantly decreased the number of surface nodules and reduced the percentage of internal melanocytic area in the lungs of mice inoculated with B16F10 cells.

Figure 4.

EAv reduces superficial and internal lung tumour of melanoma B16F10‐bearing C57BL/6 mice. Female C57BL/6 mice were intravenous inoculated with B16F10 cells and subsequently treated with EAv(100 mg/kg bw) for 21 days. (A) Images of the pathological anatomy of the lungs of representative animals treated with EAv or with 1% DMSO (control). The lungs were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde, and the number of black nodules was counted using a dissecting microscope. (B) Images of the histological sections of internal melanoma (dashed lines) in the lung tissues of representative animals treated with EAv or DMSO (1% v/v). The lungs were embedded in resin and stained with H&E (100 × magnification, n = 5, bar scale = 40 μm). The percentage of the melanocytic area was quantified using ImageJ software. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM. The groups were compared using Student's t test (**P < .01; ***P < .001)

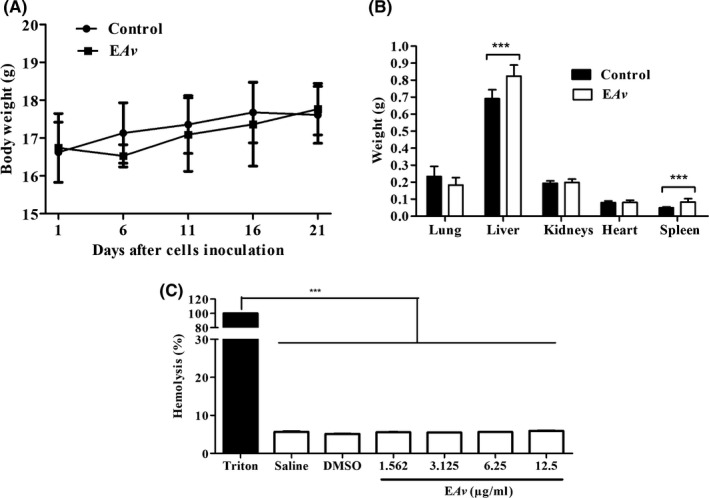

3.6. Toxicological parameters evaluated after EAv treatment

Our results showed no alteration in the body weight of animals in control and EAv‐treated mice (P > .05; Figure 5A). While the kidney, heart and lung did not show difference in their weight between groups, the weights of liver and spleen were higher in animals from EAv group than their controls (P < .001; Figure 5B). Moreover, spleen somatic index was higher in EAv‐treated animals (6.10 ± 0.23) than in control animals (3.15 ± 0.31; P < .01). Similarly, the liver somatic index was significantly higher (P < .05) in EAv‐treated animals (5.23 ± 0.10) when compared to control mice (4.37 ± 0.13; P < .05).

Figure 5.

Toxicological parameters assessed after treatment with EAv. The effect of treatment with EAv on the (A) body weight and (B) organ's weight from C57BL/6 mice‐bearing melanoma B16F10 cells. The means were compared using Student's t test (***p < 0.05). (C) For the haemolysis assay, blood sample was collected from healthy C57BL/6J mice and red blood cells were incubated at different concentrations of EAv. The saline solution was used as negative control and triton (1% v/v) as the positive control. Haemoglobin release was determined by photometric analysis at 540 nm. The data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. ***P < .001 one‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test

For serum biochemical markers, the concentration of AST was lower in EAv‐treated animals (268.30 ± 39.94 U/L) than in control animals (431.40 ± 25.86 U/L; P < .05). Additionally, EAv treatment resulted in decrease in serum urea levels to a value considered normal for healthy animals (Supporting Information S1). In the haemolysis assay, the haemoglobin release rate after the addition of 1.562‐12.5 μg/mL EAv was less than 6%, which was significantly lower (P < .001) than the percentage of erythrocyte lysis in the positive control, Triton (Figure 5C).

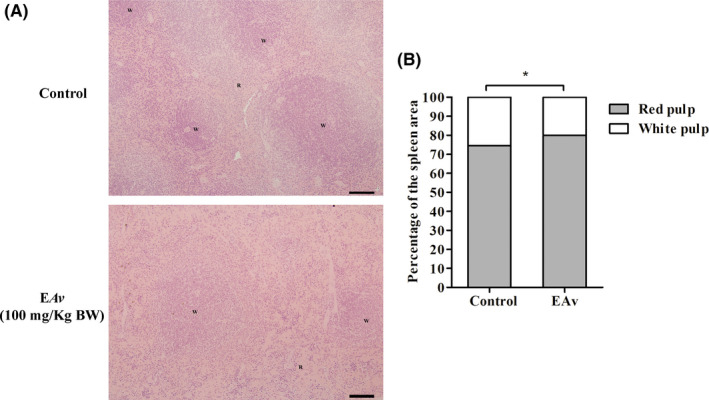

Considering the increase in the liver and spleen weights, fragments of these organs were analysed in order to verify the toxic effects of EAv. Overall, no histological alterations were observed in the spleen tissue of EAv‐treated animals when compared to control animals. In addition, morphometric analysis of the spleen revealed remodelling an enlargement of the red pulp area that implied reduction in the number and size of the white pulp follicles in the spleen of EAv‐treated mice when compared with control animals (Figure 6A; P < .05). In contrast, the percentage of red pulp area was 74.5% in the control group and 79.9% in the EAv‐treated group (Figure 6B; P < .05). Finally, liver histology was normal in both control and EAv‐treated mice.

Figure 6.

Treatment of melanoma B16F10‐bearing C57BL/6 mice with EAv increased the red pulp area in spleen. (A) Histological sections of the spleen from C57BL/6 mice‐bearing melanoma B16F10 cells treated with EAv or DMSO (1% v/v). R = red pulp, W = white pulp. The spleen was embedded in resin, 3 μm thickness, H&E staining. Scale bar = 100 μm, (B) Volumetric proportion of red and white pulp area analysed by ImageJ software. Results are expressed as the mean (n = 5). Statistical differences between groups were determined using Student's t test (*P < .05)

4. DISCUSSION

It has been reported that only 11.7% of the original forest area is remaining in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. 13 The severe decline in the forest cover is a threat to biodiversity, owing to the extinction of rare species and the subsequent loss of traditional knowledge associated with the use of medicinal plants. 30 In bioprospecting, the scientific method is reproducible when there is accurate taxonomic information and precise location of the source organism. 16 The great feature of our library of extracts is the traceability of the trees in the forest by GPS, which allows the supply of more plant material when needed, as the collected samples are always leaves and stems, but never the whole plant. In addition, the standardization of the extraction method, as proposed by McCloud 5 and also adopted by us, ensures the preservation of the physicochemical properties of the extract sources of natural products. The species of C. sylvestris 31 and A. arborescens 32 are already known for their anticancer activities. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that reports the cytotoxic and antimetastatic effects of A. velutina, a plant species typical of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. 33 In this study, a hit rate of 6.1% was obtained based on the number of plant species with moderate cytotoxic activity amongst the 49 investigated species. These data displayed the importance of the bioprospection of the Brazilian biodiversity, which has contributed to the discovery of potential agents against many diseases over several years. 34

Natural products can affect cancer cell behaviour, thereby leading to inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. 35 The phytochemical profile of EAv, obtained by FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MSn analysis, revealed the presence of phenolic compounds. The diagnostics of the mass fragments obtained in negative mode at m/z 191, 353 and 515 were characterized as quinic acid (1) and their caffeic acid derivatives caffeoylquinic acid (2) and dicaffeoylquinic acid (3), respectively. The precursor ion at m/z 191 [M‐H]‐ with fragment ions at m/z 172, m/z 127 and m/z 85 was consistent with the presence of quinic acid (1). 36 The deprotonated molecule at m/z 353 was assigned to caffeoylquinic acid (2), for which the fragmentation led to the base peak at m/z 191 ([M‐162‐H]‐) that represented the elimination of the caffeoyl moiety. 37 The product ion spectrum of the deprotonated molecule at m/z 515 showed the main MS2 product ion at m/z 353 indicating the loss of caffeoyl moiety (162 Da), while the MS3 spectrum showed main fragment at m/z 191 (loss of other caffeoyl moiety at −162 Da), indicating that the compound was dicaffeoylquinic acid (3). The precursor ion [M‐H]‐ at m/z 593 showed fragment ions at m/z 285 that resulted from the loss of the rutinose (−308 Da) and m/z 257, corresponding to kaempferol aglycone, which revealed the compound to be kaempferol‐3‐O‐rutinoside (4). 38 The other precursor ion [M‐H]‐ at m/z 609 was identified as quercetin‐3‐O‐rutinoside (5), with fragmentation of this ion yielding a base ion at m/z 301 and secondary ions at m/z 179 and 151, which was compatible with quercetin aglycone after rutinoside loss (−308 Da). Although this is the first report of these compounds in A velutina, quinic acid (1), 39 caffeoylquinic acid (2), 40 dicaffeoylquinic acid (3) 41 and quercetin‐3‐O‐rutinoside (5) 42 were identified in other plant species with antiproliferative properties. Athenaea and Aureliana were initially described in Martius's Flora Brasiliensis (Sendtner, 1846). 43 In the year of 2019, as a result of major systematic revision of the whole group, Aureliana was circumscribed within Athenaea, 44 leading the validation of Athenaea velutina proposed by D’Arcy. 45 Studies on species of the genus Aureliana and Athenaea are still limited, despite the confirmation of the presence of phenolic acids and withanolides. 46 , 47

Melanoma originates from melanocytes and is a common type of skin cancer associated with a high mortality rate owing its invasive behaviour. 22 , 48 The drugs used for the treatment of advanced stage melanoma have been shown to be inefficient as the survival rate still remains low in patients after 5 years of the onset of disease. 49 This led to the search for new anticancer drugs with antimetastatic properties. 50 EAv markedly inhibited the adhesion, migration, invasion and clonogenic potential of melanoma B16F10 cells. It is likely that the antimetastatic activity of EAv did not result from its cytotoxic effects, because this extract inhibited the proliferation of the B16F10 cells at concentrations lower than the GI50 value. 51 , 52 Melanoma B16F10 cells have high potential to colonize the lung and lead to the formation of nodules in mice when inoculated intravenously. 53 This pathological model is used widely in scientific research to investigate the effect of new antimetastatic drugs in mice. 54 , 55 EAv treatment effectively reduced the surface and internal lung black nodules in melanoma B16F10‐bearing mice by 27.6% and 74.5%, respectively. This effect appeared to result from the inhibition of cell adhesion, mobility and invasion, as observed in the in vitro assays. 56

The development of new drugs needs to be supported with toxicological safety. 57 In this study, EAv was cytotoxic to normal cells (ie Vero and NIH3T3) only at high concentrations and did not cause haemolysis, which confirmed the low toxicity to red blood cells. 28 , 58 The body weights of untreated and EAv‐treated mice were similar, suggesting that there were no relevant side effects. Typically, the occurrence of injury in liver and kidney tissues can be confirmed by the increased concentration of ALT/AST enzymes and urea/creatinine in blood plasma, respectively. 59 Based on the results obtained for the main biochemical markers related to liver and kidney functions, it was concluded that EAv did not cause any damage to these organs. In the case of liver, it was confirmed by the normal organization of hepatic tissue. 60 , 61 Moreover, our findings related to serum creatinine and urea levels indicated that EAv was not toxic to the kidney functions. 62 Finally, the increase in the relative weight of the spleen of EAv‐treated mice resulted from an increase in the area of red pulp by 5.4%, which might be related to the possible stimulation of the haematopoietic system. 63 , 64

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that EAv exhibited potentially antimetastatic activity in in vitro assays and inhibited melanoma development in C57BL/6 mice. The activities of EAv may be due to the presence of quinic acid derivatives and glycoside flavonoids. Overall, no apparent toxic effect was observed in mice after treatment. This research reinforced the importance of the investigation of plant biodiversity found in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, in which many plant species are still rarely studied for their biological activity.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AAA, GDAL, MVRCS, MM‐N, GCB, and JPVL are inventors of the pending patent BR 10 2018 005 682 4 filled in the Instituto Nacional de Propriedade Industrial—INPI/Brazil.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Tatiana Prata for the corrections in the photomicrographs and Izabella Rodrigues for the support with botanical investigations.

Almeida AA, Lima GDA, Simão MVRC, et al. Screening of plants from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest led to the identification of Athenaea velutina (Solanaceae) as a novel source of antimetastatic agents. Int J Exp Path. 2020;101:106–121. 10.1111/iep.12351

All listed authors meet ICMJE authorship criteria and that nobody who qualifies for authorship has been excluded.

Funding information

This work was supported by the FAPEMIG—Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (Grant No.: CDS—APQ‐02540‐15). Alisson A. Almeida thanks CNPq—Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico for PhD research fellowship provided (Grant No.: GD 142313/2015‐7).

REFERENCES

- 1. Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural Products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:629‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy‐Wenzig E‐V et al Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant‐derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1582‐1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harvey AL, Edrada‐Ebel R, Quinn RJ. The re‐emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:111‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen B. A new golden age of natural products drug discovery. Cell. 2015;163:1297‐1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCloud TG. High throughput extraction of plant, marine and fungal specimens for preservation of biologically active molecules. Molecules. 2010;5:4526‐4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME et al Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and the structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia . J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2325‐2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Plants as a source of anti‐cancer agents. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:72‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mans DRA, Da Rocha AB, Schwartsmann G. Anti‐cancer drug discovery and development in Brazil: targeted plant collection as a rational strategy to acquire candidate anti‐cancer compounds. Oncologist. 2000;5:185‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eisenberg DM, Harris ES, Littefield BA et al Developing a library of authenticated Traditional Chinese Medicinal (TCM) plants for systematic biological evaluation rationale, methods and preliminary results from a Sino‐American collaboration. Fitoterapia. 2011;82:17‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yadav SK, Mishra GC. Biodiversity management open avenues for bioprospecting. Int J Agric Food Sci Technol. 2013;4(6):635‐642. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joly CA, Metzger JP, Tabarelli M. Experiences from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest: ecological findings and conservation initiatives. New Phytol. 2014;204:459‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG et al Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853‐858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ribeiro MC, Metzger JP, Martensen AC et al The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: How much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biol Conserv. 2009;142:1141‐1153. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramesha BT, Gertsch J, Ravikanth G et al Biodiversity and chemodiversity: future perspectives in bioprospecting. Curr Drug Target. 2011;12(11):1515‐1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. David B, Wolfender J‐L, Dias DA. The pharmaceutical industry and natural products: historical status and new trends. Phytochem Rev. 2015;14:299‐315. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leal MC, Hilário A, Munro MHG et al Natural products discovery needs improved taxonomic and geographic information. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:747‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bolzani VS, Valli M, Pivatto M, Viegas C Jr. Natural products from Brazilian biodiversity as a source of new models for medicinal chemistry. Pure Appl Chem. 2012;84:1837‐1846. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dutra RC, Campos MM, Santos ARS, Calixto JB. Medicinal plants in Brazil: pharmacological studies, drug discovery, challenges and perspectives. Pharmacol Res. 2016;112:4‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simão MVRC, Fonseca RS, Almeida AA et al Árvores da Mata Atlântica: Livro Ilustrado Para Identificação de Espécies Típicas de Floresta Estacional Semidecidual, 2017. Manaus, Brazil, pp.234.

- 20. LEFB . Flora do Brasil 2020 em construção. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro; 2018. http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/. Accessed on: 06 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Meth. 1983;16:693‐697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui S, Wang J, Wu Q et al Genistein inhibits the growth and regulates the migration and invasion abilities of melanoma cells via the FAK/paxillin and MAPK pathways. Oncotarget. 2017;8:21674‐21691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Humphries MJ. Cell‐substrate adhesion assays. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 1998;9.1.1‐9.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Albini A, Benelli R. The chemoinvasion assay: a method to assess tumor and endothelial cell invasion and its modulation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:504‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Franken NAP, Rodermond HM, Stap J et al Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro . Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2315‐2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Souza ACF, Marchesi SC, Lima GDA, Neves MM. Effects of arsenic compounds on microminerals content and antioxidant enzyme activities in rat liver. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;183(2):305‐313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabilova TO, Sen'kova AV, Nikolin VP et al Antitumor and antimetastatic effect of small immunostimulatory RNA against B16 melanoma in mice. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cao J, Zhang Y, Yanke S et al A pH‐dependent antibacterial peptide release nano‐system blocks tumor growth in vivo without toxicity. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Motta LB, Furlan CM, Santos DYAC et al Antiproliferative activity and constituents of leaf extracts of Croton sphaerogynus Baill. (Euphorbiaceae). Indus Crop Prod. 2013;50:661‐665. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buenz EJ, Verpoorte R, Bauer BA. The ethnopharmacologic contribution to bioprospecting natural products. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;58:19.1‐19.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oberlies NH, Burgess JP, Navarro HA et al Novel bioactive clerodane diterpenoids from leaves and twigs of Casearia sylvestris . J Nat Prod. 2002;65:95‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Veras ML, Bezerra MZB, Lemos TLG et al Cytotoxic withaphysalins from leaves of Acnistus arborescens . J Nat Prod. 2004;67:710‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de Carvalho LÁF, Costa LHP, Duarte AC. Diversidade taxonômica e distribuição geográfica das solanáceas que ocorrem no Sudeste Brasileiro (Acnistus, Athenaea, Aureliana, Brunfelsia e Cyphomandra). Rodriguesia. 2001;52:31‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newman DJ. The influence of Brazilian biodiversity on searching for human use pharmaceuticals. J Braz Chem Soc. 2016;28:402‐414. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen H, Liu RH. Potential mechanisms of action of dietary phytochemicals for cancer prevention by targeting cellular signaling transduction pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(13):3260‐3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saldanha LL, Vilegas W, Dokkedal AL. Characterization of flavonoids and phenolic acids in Myrcia bella Cambess. using FIA‐ESI‐IT‐MSn and HPLC‐PAD‐ESI‐IT‐MS combined with NMR. Molecules. 2013;18:8402‐8416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Catarino MD, Silva AMS, Saraiva SC et al Characterization of phenolic constituents and evaluation of antioxidant properties of leaves and stems of Eriocephalus africanus . Arab J Chem. 2018;11:62‐69. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gontijo DC, Leite JPV, Nascimento MFA et al Bioprospection for antiplasmodial activity, and identification of bioactive metabolites of native plants species from the Mata Atlântica biome. Brazil. Nat Prod Res. 2019. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1633645. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gundala SR, Yang C, Lakshminarayana N et al Polar biophenolics in sweet potato greens extract synergize to inhibit prostate cancer cell proliferation and in vivo tumor growth. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2039‐2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun Y, Li H, Hu J et al Qualitative and quantitative analysis of phenolics in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum and their antioxidant and antiproliferative activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:10507‐10515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Filip R, Ferraro G, Manuele MG, Anesini C Ilex brasiliensis: phytochemical composition and mechanism of action against the proliferation of a lymphoma cell line. J Food Biochem. 2008;32:752‐765. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ding Y, Ren K, Dong H et al Flavonoids from persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) leaves inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in PC‐3 cells by activation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial apoptosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;275:210‐217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sendtner O. Solanaceae et Cestrinneae In: Von Martius CFP. ed. Flora Brasiliensis. 1846;10:1‐338. Monachii, Germany:Lipsiae, Frid. Fleischer. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rodrigues IMC, Knapp S, Stehmann JR. The nomenclatural re‐establishment of Athenaea Sendtn. (Solanaceae) with a nomenclatural synopsis of the genus. Taxon. 2019;68(4):839‐846. 10.1002/tax.12089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. D’Arcy WG. Taxonomy and biogeography In: D’Arcy WG. ed. Solanaceae Biology and Systematics. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1986:1‒4. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Almeida‐Lafetá RC, Ferreira MJP, Emerenciano VP, Kaplan MAC. Withanolides from Aureliana fasciculate var. fasciculata . Helv Chim Acta. 2010;93:2478‐2487. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Silva EL, Almeida‐Lafetá RC, Borges RM, Staerk D. Athenolide A, a new steroidal lactone from the leaves of Athenaea martiana (Solanaceae) determined by means of HPLC‐HR‐MS‐SPENMR analysis. Chem Biodivers. 2018;15(1):e1700455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kumar S, Weaver VM. Mechanics, malignancy and metastasis: the force journey of a tumor cell. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:113‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maio M, Grob J‐J, Aamdal S et al Five‐Year survival rates for treatment‐naive patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1191‐1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim A, Im M, Yim N‐H, Ma JY. Reduction of metastatic and angiogenic potency of malignant cancer by Eupatorium fortunei via suppression of MMP‐9 activity and VEGF production. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marvibalgi M, Amini N, Supriyanto E et al Antioxidant activity and ROS‐dependent apoptotic effect of Scurrula ferruginea (Jack) Danser methanol extract in human breast cancer cell MDA‐MB‐231. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lu C‐T, Leong P‐Y, Hou T‐Y et al Ganoderma immunomodulatory protein and chidamide down‐regulate integrin‐related signaling pathway result in migration inhibition and apoptosis induction. Phytomedicine. 2018;51:39‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. George KG, Kuttan G. Inhibition of pulmonar metastasis by Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC: An in vivo experimental study. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:123‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Danciu C, Oprean C, Coricovac DE et al Behaviour of four different B16 murine melanoma cell sublines: C57BL/6J skin. Int J Exp Path. 2015;96:73‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Im M, Kim A, Ma JY. Ethanol extract of baked Gardeniae Fructus exhibits in vitro and in vivo anti‐metastatic and anti‐angiogenic activities in malignant cancer cells: role of suppression of the NF‐κB and HIF‐1ɑ pathways. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:2377‐2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang H‐C, Wu D‐H, Chang Y‐C et al Solanum nigrum Linn. Water extract inhibits metastasis in mouse melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo . J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:11913‐11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Al‐Qubaisi M, Rozita R, Yeap S‐K et al Selective cytotoxicity of goniothalamin against hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells. Molecules. 2011;16:2944‐2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Casagrande JC, Macorini LFB, Antunes KA et al Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of hydroethanolic extract from Jacaranda decurrens leaves. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Qi Z‐L, Wang Z, Li W et al Nephroprotective effects of anthocyanin from the fruits of Panax ginseng (GFA) on cisplatin‐induced acute kidney injury in mice. Phytother Res. 2017;31:1400‐1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gonçalves RV, Novaes RD, Leite JPV et al Hepatoprotective effect of Bathysa cuspidate in a murine model of severe toxic liver injury. Int J Exp Path. 2012;93:370‐376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Freitas RB, Novaes RD, Gonçalves RV et al Euterpe edulis extract but not oil enhances antioxidant defenses and protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high‐fat diet in rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:8173876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fernández I, Peña A, Teso ND et al Clinical biochemistry parameters in C57BL/6J mice after blood collection from the submandibular vein and retroorbital plexus. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2010;49:202‐206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Elmore SA. Enhanced histopathology of the spleen. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:648‐655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kirstein JM, Hague MN, McGowan PM. Primary melanoma tumor inhibits metastasis through alterations in systemic hemostasis. J Mol Med. 2016;94:899‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information