Abstract

Practice guidelines on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV serodiscordant couples recommend PrEP when the viral load of the partner living with HIV is either detectable or unknown. However, adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy is inconsistent, and research has found that individuals vulnerable to HIV place value on additional protective barriers. We conducted a prospective cohort study to assess the feasibility, perceptions, and adherence associated with periconceptional PrEP use among females without HIV and their male partners living with HIV across four academic medical centers in the United States. We performed descriptive statistics, McNemar's test of marginal homogeneity to assess discordance in female/male survey responses, and Spearman's correlation to determine associations between dried blood spot levels and female self-reported adherence to PrEP. We enrolled 25 women without HIV and 24 men living with HIV (one male partner did not consent to the study). Women took PrEP for a median of 10.9 months (interquartile range 3.8–12.0) and were generally adherent. In total, 87% of women (20/23) had a dried blood spot with >700 fmol/punch or ≥4 doses/week, 4% (1/23) at 350–699 fmol/punch or 2–3 doses/week, and 9% (2/23) at <350 fmol/punch or <2 doses/week (correlation between drug levels and adherence is based on prior data). Dried blood spot levels closely aligned with self-reported adherence (Spearman's rho = 0.64, p = 0.001). There were 10 pregnancies among 8 participants, 4 of which resulted in spontaneous abortions. There was one preterm delivery (36 5/7 weeks), no congenital abnormalities, and no HIV transmissions. Ten couples (40%) were either lost to follow-up or ended the study early. Overall, women attempting conception with male partners living with HIV in the United States are interested and able to adhere to PrEP as an additional tool for safer conception.

Keywords: PrEP, conception, HIV, serodiscordant, serodifferent

Introduction

In 2017, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated their clinical practice guidelines for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in the United States.1,2 The updated guidelines reflect the strong evidence base for combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and viral suppression for partners living with HIV (treatment as prevention) as an important HIV prevention tool for partners without HIV seeking to conceive with their partners living with HIV (otherwise known as “serodiscordant” couples).1,3,4 Recognizing the effectiveness of treatment as prevention,3,5–8 the revised guidelines recommend PrEP as an additional prevention tool when the viral load of the partner living with HIV is either detectable or unknown.1,9

Given that less than half of people living with HIV have consistently undetectable viral load counts, with a high proportion cycling in and out of HIV care, couples might choose other methods to reduce risk of HIV transmission.10,11 Further, it is not always feasible to ensure that partners are “undetectable” throughout the period of risk.12 In situations where the partner with HIV is either inconsistently on cART or the plasma viral load status is unknown, PrEP and other risk-reduction options can add meaningful value.1,12,13 PrEP is especially beneficial for partners where safer conception strategies have historically been limited. While other conception options for couples in this context include assisted reproduction with special sperm washing procedures to reduce HIV risk,14,15 these methods are expensive, not typically covered by insurance, and are often geographically limited.16,17

In addition, recent studies suggest that when compared with treatment as prevention, serodiscordant couples on average prefer methods with additional protective barriers.13,18,19 Individuals vulnerable to HIV place value on the “reassurance” of additional protective barriers, even when the partner with HIV is consistently on cART. With the forthcoming generic version of PrEP,20 offering women PrEP provides an effective and accessible option for safer conception. The medication's effectiveness, however, hinges on adherence, and previous studies on PrEP adherence among women in general are mixed.21–25 Our objective was to examine the acceptance, feasibility, and adherence to periconceptional PrEP among women without HIV with male partners living with HIV. We also sought to measure pregnancy outcomes associated with periconceptional PrEP use.

Methods

Between July 2014 and May 2016, we enrolled 25 women without HIV and 24 men living with HIV desiring conception from four urban academic medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts, Baltimore, Maryland, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Chicago, Illinois. Two sites were located within infectious disease (ID) clinics (Boston and Philadelphia), and two within colocated obstetrics and gynecology and ID clinics (Baltimore and Chicago). Female participants without HIV were in a relationship with a male partner living with HIV and had chosen PrEP for safer conception. Partners living with HIV were clinically engaged in HIV care with HIV-1 RNA loads <100 copies/mL over the study period. All participants were of age ≥18 years. Clinicians conducted safer conception counseling before couples' enrollment in the study, which included education on ovulation prediction and timing of condomless intercourse, risks of seroconversion and perinatal transmission, and the spectrum of safer conception options. Once couples decided on PrEP, investigators consented and enrolled participants into the study and employed the CDC protocol to monitor participants' preconception course on PrEP.1,26–28

Since semen abnormalities are more common among men with HIV than those without HIV, DHHS and CDC recommend considering semen analysis for male partners with HIV before conception is attempted.1,26–28 While we did not offer semen analysis as part of the protocol, we encouraged study participants to seek evaluation separately. Providers initiated PrEP ≥30 days before timed condomless intercourse during peak fertility and recommended patients continue PrEP for a minimum of 28 days after the last sexual exposure.1,26–28 Participants underwent baseline screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including syphilis, hepatitis B and C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia (semiannual visits for selected STIs). We also tested female participants for trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis at baseline. We tested women for HIV at baseline, every 3 months over the study period, and 6 and 16 weeks after last unprotected sexual exposure.1,26 We conducted medical record chart review for male participants' CD4 count/μL and HIV-1 RNA copies/mL at baseline and every 3 months over the study period. Providers considered the continuation of PrEP during pregnancy on an individual basis.

We tracked female participants' monthly PrEP adherence and side effects. The study team collected dried blood spots to assess intracellular tenofovir-diphosphate in red blood cells 1 month after treatment and after a positive pregnancy test. Tenofovir-diphosphate (TFV-DP) values obtained before steady state (before week 8) were adjusted to estimate steady state dosing based on a 17-day half-life (tenofovir-diphosphate measured/1 − e−0.04 × day of therapy).29 Our interpretations of tenofovir-diphosphate in red blood cells measured with dried blood spots were as follows: <350 fmol/punch, <2 doses/week; 350–699 fmol/punch, 2–3 doses/week; and >700 fmol/punch or ≥4 doses/week, on average (correlation between drug levels and adherence is based on prior data).24,30,31

We followed female participants up to 12 months on tenofovir/emtricitabine or until completion of a pregnancy. We administered modified baseline knowledge and attitude surveys from the Partner's PrEP study to each participant.32 We performed descriptive statistics to summarize study outcomes on participant demographics, preconception attitudes and practices, and pregnancy. We performed McNemar's test of marginal homogeneity to assess discordance between couples' relationship dynamics and fears of HIV transmission, and Spearman's correlation test to determine linear associations between our study outcome on dried blood spot concentrations and female self-reported adherence to PrEP at month 1 of follow-up. Site Institutional Review Boards approved study activities before study initiation, and we registered the study at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02233192).

Results

Over the course of the study, 25 women without HIV and 24 men living with HIV enrolled (24 HIV serodiscordant pairs, 1 male partner did not consent to the study). Characteristics of study participants are depicted in Table 1. Ten couples (40%) were either lost to follow-up (six did not come back for clinical care/clinical staff could not reach them as part of standard clinical protocols) or ended the study early (four ended the study early due to: no longer wanting to conceive, medical issue, change of insurance, and seeking assisted reproduction). Participants lost to follow-up were less likely to be married compared with those who stayed in the study (p = 0.049); however, there were no other demographic differences between the two groups. Couples in our cohort were older [female interquartile range (IQR): 32–38; male IQR: 36–48] and predominantly non-Hispanic black (>60%, see Table 1). The majority of both men and women enrolled were employed, with a higher proportion of female partners attending at least some college, college, or graduate school compared with their male partners (p = 0.03). The median relationship duration was 4 years. Most participants were married, and a sizable minority had children already. Two female participants had a confirmed reactive hepatitis C result (referred to specialists for treatment), and one had a confirmed positive trichomoniasis result (treated). These participants were part of the cohort who were either lost to follow-up or ended the study early.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants at Four US Sites: Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia

| Females |

Males |

|

|---|---|---|

| N = 25 | N = 24 | |

| Study participation characteristics | ||

| Site of recruitment | ||

| Boston | 6 (24) | 6 (25) |

| Philadelphia | 10 (40) | 9 (37) |

| Baltimore | 4 (16) | 4 (17) |

| Chicago | 5 (20) | 5 (21) |

| Lost to follow-up/ended study early | 10 (40) | 10 (42) |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age at enrollment (median/IQR) (years) | 35 (32–38) | 41.5 (36–48) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 16 (64) | 15 (62) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 4 (16) | 5 (21) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 3 (12) | 3 (12) |

| Asian | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

| Education and employment | ||

| Some high school | 2 (8) | 5 (21) |

| High school | 5 (20) | 9 (37) |

| Some college | 4 (16) | 2 (8) |

| College | 8 (32) | 5 (21) |

| Graduate school | 6 (24) | 3 (12) |

| Currently employeda | 21 (84) | 18 (75) |

| Relationship information | ||

| Time in relationship (median/IQR) (months) | 48 (12–102) | |

| Married | 14 (56) | 14 (54) |

| Has children | 8 (33) | 10 (42) |

| Number of children (median/IQR) | 1.5 (1–2) | 3 (2–4) |

| Has children with current partner | 2 (25) | 2 (10) |

| Clinical characteristics at enrollment | ||

| Illicit drug use in the past year | 5 (20) | 5 (23) |

| CD4 count (/μL) (median/IQR) (n = 23) | — | 569 (485.5–734.5) |

| Viral load (copies/mL) (range) (n = 22) | — | <20–70 |

| Participants with <100 copies/mL (HIV RNA level) (n = 22) | — | 22 (100) |

| Sperm motility percentage (median/IQR) (n = 6)b | — | 66 (41.25–80.5) |

Data presented as median (IQR) or n (%).

Full-time and part-time employment.

Two additional participants reported normal results from semen analysis, but we were not able to validate with medical records.

IQR, interquartile range.

Male participants were consistently on cART with a median baseline CD4 count of 569/μL (IQR: 485.5–734.5) over the study period, and 92% (22/24) maintained a confirmatory HIV-1 RNA load <100 copies/mL. Six (25%) men completed a semen analysis with a median motility of 66% (IQR: 41–81), indicative of normal levels of sperm motility. The majority of men were unable to complete a semen analysis due to out-of-pocket costs and logistic challenges in obtaining the test since patients were not enrolled in formal fertility programs.

Of the 25 women without HIV enrolled in the study, 8 women had 10 pregnancies, with a median time to pregnancy of 11 months, 4 of which resulted in spontaneous abortions during the first trimester. There were six live births (median birthweight 7.99 pounds, IQR: 6.81–8.60), one preterm delivery (36 5/7 weeks), no congenital abnormalities, and no HIV transmissions. The median age of women who became pregnant was 33.5 (IQR: 30.0–34.8) (five of which were nulliparous); male partners' median age was 35.5 (IQR: 32.5–39.8). For couples who did not become pregnant, the median age of women was 37.0 years (IQR: 21.0–42.5) (four of which were nulliparous); male partners' median age was 46 (IQR: 40–48). In addition, one couple was not able to attempt to conceive for 6 months due to travel; this female participant was 43 and her partner was 53.

Characteristics of pregnancy attempts and PrEP beliefs are shown in Table 2. Nineteen women (76%) were attempting conception for the first time with their partners. Before enrolling in our study, few women (36%) had previously employed HIV risk reduction methods. Reasons for choosing PrEP for conception included safety (42%) and affordability (21%). If cost were not a concern, participants were evenly divided on choosing PrEP versus other risk-reduction methods. Twenty-four percent of women had “no concerns” about PrEP for conception; about one-third expressed their concerns about HIV transmission (36%) and side effects (32%). 56% (14/25) of participants reported experiencing side effects; headaches and gas were the most commonly reported (Table 3).

Table 2.

Preconception Attitudes and Practices Reported by Female Participants

| Female participants |

|

|---|---|

| (N = 25) (%) | |

| Attempted conception with partner before study | |

| Yes | 6 (24) |

| No | 19 (76) |

| Risk-reduction methods in the past (not necessarily with current partner) | |

| Partner on cART to reduce VL | 5 (20) |

| Sperm wash + IUI | 3 (12) |

| Condom use | 1 (4) |

| None | 16 (64) |

| Referred to a fertility clinic before study | 5 (20) |

| Reasons for using PrEP for conception (n = 24) | |

| Safe | 10 (42) |

| Affordable | 5 (21) |

| Good data/effective prevention strategy | 3 (12) |

| Othera | 6 (25) |

| If both sperm wash and PrEP were available through insurance method, which would be chosen (n = 23) | |

| PrEP | 9 (39) |

| SW/IUI | 7 (30) |

| No preference | 7 (30) |

| Fear or concerns about using PrEPb | |

| HIV transmission | 9 (36) |

| Side effects | 8 (32) |

| Difficulty taking tablet daily | 4 (16) |

| Other | 9 (36) |

| None | 6 (24) |

Other reasons included were as follows: wanting to seek natural conception method, have not yet decided, clinic or doctor recommended, or stated “other” only.

Participants could select more than one choice.

cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; IUI, intrauterine insemination; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SW, sperm wash; VL, viral load.

Table 3.

Duration, Adherence, and Side Effects of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

| Female participants |

|

|---|---|

| (N = 25) (%) | |

| Months on PrEP before conceptiona (median/IQR) | 10.9 (3.8–12.0) |

| DBS, 1-month follow-up (n = 23) | |

| >700 fmol/punch | 20 (87) |

| 350–699 fmol/punch | 1 (4) |

| <350 fmol/punch | 2 (9) |

| DBS at pregnancy (n = 8 pregnancies) | |

| >700 fmol/punch | 7 (88) |

| 350–699 fmol/punch | 1 (13) |

| <350 fmol/punch | 0 (0) |

| Experienced a medication side effect at the 1-month follow-up visitb | 14 (56) |

| PrEP use during pregnancy and postpartum (n = 8) | |

| Remained on PrEP throughout pregnancy | 2 (25) |

| Remained on PrEP postpartum | 2 (25) |

We followed participants until they achieved pregnancy or up to 12 months per study protocol. Due to an adverse reaction to FTC (emtricitabine), one woman was on tenofovir 300 mg only. This value includes seven women who stopped PrEP and reinitiated (median monthly cycle on PrEP for this group was 12; IQR: 11.16–12.5). This value also includes five lost-to-follow-up participants whose stop dates were estimated based on prescription refills.

Side effects included were as follows: headaches (79%), gas (64%), weight gain (21%), and weight loss (14%). Patients could choose more than one symptom, and thus column percentages sum to >100.

DBS, dried blood spot; IQR, interquartile range; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

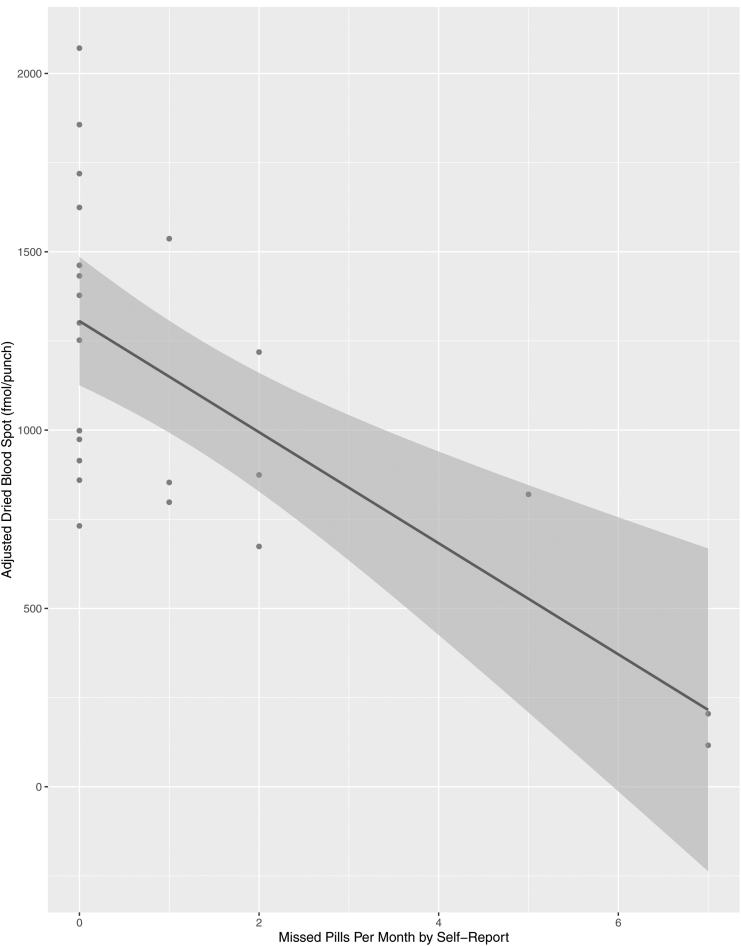

Female participants took PrEP for a median of 10.9 months (IQR 3.8–12.0) and were generally adherent. Once we adjusted for steady state, 87% of women (20/23) had a dried blood spot with >700 fmol/punch or ≥4 doses/week, 4% (1/23) at 350–699 fmol/punch or 2–3 doses/week, and 9% (2/23) at <350 fmol/punch or <2 doses/week on average. Median self-reported missed dose of PrEP at month 1 was 0 (IQR: 0–1.5); 61% (14/23) reported <1 missed dose at the first month of follow-up. Month-one median adjusted dried blood spot drug level was 998 (IQR: 837–1447) (Table 3). Dried blood spot levels closely aligned with self-reported adherence, with a moderate-to-strong correlation between dried blood spot levels and self-report (r = 0.64, p = 0.001) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dried blood spot level versus self-reported pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence (N = 23). This figure represents the correlation between self-reported adherence and adjusted dried blood spot adherence levels.

After a positive pregnancy test, we collected nine dried blood spot samples for eight women. One woman chose to discontinue PrEP on the day of pregnancy detection, and her dried blood spot was completed over 30 days postdiscontinuation. We therefore reported on eight dried blood spot pregnancy samples among seven women with a median of 8.5 days between pregnancy detection and dried blood spot draw dates (Table 3). Of these pregnancies, 88% of women (7/8) had a dried blood spot with >700 fmol/punch or ≥4 doses/week and 13% (1/8) at 350–699 fmol/punch or 2–3 doses/week. Of the eight women who became pregnant in our cohort, two chose to remain on PrEP throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

When we asked participants about their current relationship dynamics at study enrollment (Table 4), a high proportion of women and men reported that having a child with their partner was important to their relationship; however, 92% of women (22/24) and 100% of men (24/24) did not feel that having a child was a prerequisite to stay together. While couples were more evenly divided on whether they would willingly engage in unprotected intercourse before PrEP availability, there were significant differences among women and men in regard to HIV transmission concerns. For instance, while women expressed concern in contracting HIV from their partners, men expressed even greater concern in transmitting the virus (p = 0.01) and were more inclined to think about transmission when engaging in intercourse compared with women (p = 0.03).

Table 4.

Couples' Relationship Dynamics

| Females |

Males |

p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 25 (%) | N = 24 (%) | ||

| I want to have a child with my partner | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 25 (100) | 24 (100) | — |

| I believe that having a child with my partner is important to our relationship | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 17 (68) | 16 (67) | 0.6547 |

| If I do not have a child with my partner, I worry that we will not stay together | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 2 (8) (missing = 1) | 0 (0) | — |

| Before PrEP, I would be willing to have vaginal sex without a condom with my partner | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 13 (52) | 11 (46) | 0.4142 |

| Getting/giving HIV from/to my partner worries/scares me | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 16 (67) (missing = 1) | 22 (92) | 0.0143 |

| Every time I have intercourse with my partner, I think about getting infected/infecting my partner with HIV | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 10 (40) | 15 (63) | 0.0339 |

| Sometimes I avoid intercourse with my partner because I am afraid I could get infected/infect my partner with HIV | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 7 (28) | 10 (42) | 0.1025 |

| I am afraid I could be infected/infect my partner with HIV by undergoing this method | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 10 (40) | 9 (38) | 1.0000 |

| I worry that my partner/I will not be here in the future to take part in raising a child | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 11 (44) | 7 (30.43) (missing = 1) | 0.3657 |

McNemar's test to compare male and female participants. Male sample = 24 since one female's partner did not participate.

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Discussion

Our results suggest that women seeking conception with partners with HIV desired and adhered to PrEP amid their partners' steady use of cART. Objective levels of PrEP adherence closely aligned with self-reported adherence, with a moderate-to-strong correlation between dried blood spot levels and self-report. Couples choosing PrEP for conception from four urban academic medical centers were typically older and non-Hispanic black.

While previous studies on PrEP adherence among women in general are mixed,21,23–25,33,34 we observed high adherence among our cohort of women seeking conception. These findings align with other studies that have assessed adherence among women seeking conception in African settings.35–37 Our study is the first to our knowledge to prospectively assess PrEP for safer conception as part of a study protocol in the United States, building on previous studies that characterize this patient population across other settings.36–41

Couples enrolled in our study may have had diminished fertility associated with age, which is an important characteristic given potential increased exposure to achieve a pregnancy. The higher than expected rates of spontaneous abortion (SAB) could be attributed to both maternal and paternal age,42 and less likely linked to PrEP use.43 Previous studies have reported racial/ethnic disparities in the use of PrEP, which limits the medication's full benefits.2,44 Since black/African American women are disproportionately affected by HIV, strategies to improve uptake and adherence to PrEP among racial/ethnic minorities should be prioritized.2 Before enrolling in our study, few couples had previously employed HIV risk-reduction methods. This finding may reveal important gaps in health care delivery. Other studies have explored possible underlying reasons for prior risk-taking behaviors.18,45 Public health campaigns and implementation strategies to improve knowledge and access to PrEP and other risk-reduction methods for HIV serodiscordant couples are critical to ensure those vulnerable to HIV receive appropriate preventive care.46–49

Based on previous studies, the potential value of PrEP and the reassurance associated with it extend beyond that of a partner's undetectable viral load.13,18,19 Despite the strong evidence behind treatment as prevention, women might not be in a position to regularly monitor their partner's behavior nor consistently do so over time.5,10 Future research is needed to disentangle why serodiscordant couples seeking conception might prefer additional modes of protection on top of their partner taking cARTs (i.e., Is it because of concerns regarding the fetus or fear of horizontal transmission?). Considering patient preferences and ensuring a more uniform decision-making experience with a range of safer conception options could ultimately improve HIV and pregnancy outcomes for women and their children.

Our study uniquely characterizes PrEP use for safer conception among HIV serodiscordant couples in the United States. The excellent adherence to PrEP among women throughout preconception points to the need for future implementation research to optimize HIV providers' awareness of their patients' preferences for safer conception as well as linkage to preconception care for serodiscordant couples.

This study is not without limitations. Our sample of 25 women without HIV and 24 men living with HIV desiring conception was small, which limited our generalizability and ability to test further assumptions. The small sample size may also point to the lack of public awareness about safer conception modalities and the role of preconception consultation. Participant lost to follow-up further limited our sample size to be able to assess trends over time. We did not provide incentives to keep patients enrolled, and no additional attempt was made to contact them outside of standard clinical protocols. The enrolled couples could be a product of selection bias, as the male partners living with HIV, in particular, represent a subgroup of men with HIV-1 RNA loads <100 copies/mL over the study period. “Protocol-driven” biases could have influenced motivational and adherence factors among participants. Moreover, while couples tracked ovulation through urine ovulation predictor kits and mobile apps, we did not reliably measure this outcome. Further, dried blood spot adherence categorizations for efficacy are based on studies of men who have sex with men, and future studies are needed to determine the clinical relevance of these adherence categories in women.24,30,31

Notwithstanding these limitations, women without HIV desiring conception with male partners living with HIV in the United States are interested and able to adhere to PrEP as an additional tool for safer conception. This study informs clinical counseling and future research needs regarding PrEP for conception in serodiscordant couples in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We thank our study participants for their willingness to participate in open and honest communication about their experiences.

Disclaimer

The funder did not influence the study design, data collection, or interpretation of the data in this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.S. led an investigator-initiated grant sponsored by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (IN-US-276-1262). The funder did not influence the study design, data collection, or interpretation of data. P.L.A. has received personal fees and research grants from Gilead Sciences.

Funding Information

This study was an investigator-initiative grant sponsored by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (IN-US-276-1262). Dr. J.C. was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) R01AI110371.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2017 Update: A Clinical Practice Guideline. 2017. Available at: https://cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf (Last accessed September16, 2018).

- 2. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection. JAMA 2019;321:2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of hiv transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2016;316:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med 2016;375:830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leech AA, Burgess JF, Sullivan M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention for conception in the United States. AIDS 2018;32: 2787–2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodger A, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in MSM couples with suppressive ART: The PARTNER2 study extended results in gay men. Lancet 2019;393:2428–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The Lancet HIV. U = U taking off in 2017. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCray E. Dear Colleague: September 27, 2017. | What's New | About the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention (DHAP) | HIV/AIDS | CDC. 2017. Available at: https://cdc.gov/hiv/library/dcl/dcl/092717.html (Last accessed November18, 2018)

- 9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Adherence Limitations to Treatment Safety and Efficacy Adult and Adolescent ARV. AIDSinfo. 2018. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv/30/adherence (Last accessed November18, 2018).

- 10. Yehia BR, Stephens-Shields AJ, Fleishman JA, et al. The HIV care continuum: Changes over time in retention in care and viral suppression. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matthews LT, Beyeza-Kashesya J, Cooke I, et al. Consensus statement: Supporting safer conception and pregnancy for men and women living with and affected by HIV. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1713–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What's love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;59:463–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loutfy M, Kennedy VL, Sanandaji M, et al. Pregnancy planning preferences among people and couples affected by human immunodeficiency virus: Piloting a discrete choice experiment. Int J STD AIDS 2018;29:382–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zafer M, Horvath H, Mmeje O, et al. Effectiveness of semen washing to prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission and assist pregnancy in HIV-discordant couples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2016;105:645–655.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu M-Y, Ho H-N. Cost and safety of assisted reproductive technologies for human immunodeficiency virus-1 discordant couples. World J Virol 2015;4:142–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Disparities in access to effective treatment for infertility in the United States: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2015;104:1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leech AA, Bortoletto P, Christiansen C, et al. Assessing access to assisted reproductive services for serodiscordant couples with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Fertil Steril 2018;109:473–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bazzi AR, Drainoni M-L, Sullivan M, Leech AA, Biancarelli DL. Experiences using pre-exposure prophylaxis for safer conception among HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:348–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quaife M, Eakle R, Cabrera Escobar MA, et al. Divergent preferences for HIV prevention: A discrete choice experiment for multipurpose HIV prevention products in South Africa. Med Decis Making 2018;38:120–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. FDA Approves First Generic Truvada in US. Medscape. 2017. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/881368 (Last accessed September16, 2018)

- 21. Pyra M, Brown ER, Haberer JE, et al. Patterns of oral PrEP adherence and HIV risk among Eastern African women in HIV serodiscordant partnerships. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3718–3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, et al. FEM-PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:324–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts ST, Haberer J, Celum C, et al. Intimate partner violence and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in African Women in HIV serodiscordant relationships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;73:313–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:820–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: A substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States–2017 Update: Clinical Providers Supplement. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2017.pdf (Last accessed September16, 2018).

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States: 2014. Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014. Available at: http://cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf (Last accessed August25, 2015)

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States: 2014. Clinical Providers Supplement. 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2017.pdf (Last accessed August25, 2015)

- 29. Anderson PL, Liu AY, Castillo-Mancilla JR, et al. Intracellular tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate in dried blood spots following directly observed therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62:pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, et al. An HIV preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:21–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, et al. FEM-PrEP: Adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:324–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matthews LT, Heffron R, Mugo NR, et al. High medication adherence during periconception periods among HIV-1-uninfected women participating in a clinical trial of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67:91–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mugo NR, Hong T, Celum C, et al. Pregnancy incidence and outcomes among women receiving preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:362–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heffron R, Thomson K, Celum C, et al. Fertility intentions, pregnancy, and use of PrEP and ART for safer conception among East African HIV serodiscordant couples. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1758–1765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heffron R, Pintye J, Matthews LT, Weber S, Mugo N. PrEP as peri-conception HIV prevention for women and men. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13:131–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vernazza PL, Graf I, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Geit M, Meurer A. Preexposure prophylaxis and timed intercourse for HIV-discordant couples willing to conceive a child. AIDS 2011;25:2005–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Del Romero J, Baza MB, Río I, et al. Natural conception in HIV-serodiscordant couples with the infected partner in suppressive antiretroviral therapy: A prospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seidman DL, Weber S, Timoney MT, et al. Use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis during the preconception, antepartum and postpartum periods at two United States medical centers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:632..e1–e632.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de La Rochebrochard E, Thonneau P. Paternal age and maternal age are risk factors for miscarriage; results of a multicentre European study. Hum Reprod 2002;17:1649–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heffron R, Mugo N, Hong T, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and infant growth among babies with in-utero exposure to tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. AIDS 2018;32:1707–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings KM, Hawkins T, McCallister S, Mera Giler R.. ASM/ICAAC: Racial Characteristics of FTC/TDF for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users in the US. Available at: http://natap.org/2016/HIV/062216_02.htm (Last accessed June28, 2019)

- 45. Drainoni M-L, Biancarelli DL, Leech AA, Sullivan M, Bazzi AR. Implementing a pre-exposure prophylaxis intervention for safer conception among HIV serodiscordant couples: Recommendations for health care providers. J Health Dispar Res Pract 2018;11:19–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laurence J. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:487–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koren DE, Nichols JS, Simoncini GM. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and women: Survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in an urban obstetrics/gynecology clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khosropour CM, Backus KV, Means AR, et al. A pharmacist-led, same-day, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis initiation program to increase PrEP uptake and decrease time to PrEP initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020;34:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: Implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019;33:507–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]