Abstract

Introduction

Vasa previa is a condition where fetal blood vessels run unprotected in the membranes, outside the umbilical cord, and cross the internal opening of the cervix. During rupture of membranes, these vessels can rupture and put the baby at serious risk of severe blood loss and death. Numerous studies are being conducted to improve diagnostic modalities and establish clear management plans to improve pregnancy outcomes. However, the lack of a standardised set of outcomes for studies on vasa previa makes it difficult to compare study findings and draw meaningful conclusions. Through this project, we will be developing a core outcome set for studies on pregnant women with vasa previa (COVasP).

Methods and analysis

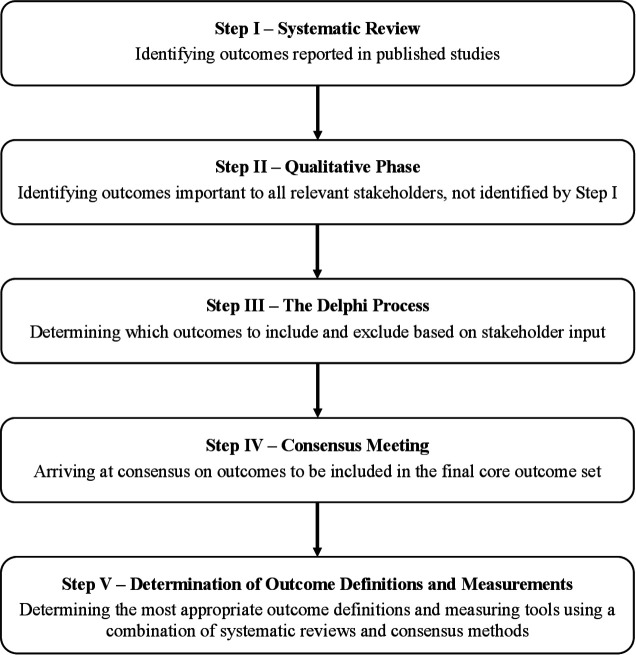

The development of COVasP will involve five steps. The first will be a systematic review, in which we will generate a long list of outcomes based on published studies in pregnancies complicated with vasa previa. The second will involve in-depth interviews with current and former patients, their family members and healthcare providers who care for these patients. This will be followed by a two-round Delphi survey, which will aim to narrow down the long list of outcomes into those considered important by four groups of ‘stakeholders’: (1) patients, family members and patient advocates/representatives, (2) healthcare providers, (3) researchers, epidemiologists and methodologists and (4) other stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in the management of these pregnancies such as administrators, guideline developers and policymakers. The fourth step will involve a face-to-face consensus meeting using a nominal group approach to establish a finalised core outcome set. The final step will involve measuring and defining the identified outcomes using a combination of systematic reviews and Delphi surveys.

Ethics and dissemination

This study as well as consent forms for stakeholder participation have received approval from the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB number 18-0173-E) on 05 September 2018 and the Human Research Ethics Committee at The University of Technology Sydney, Australia on 30 July 2019 (UTS HREC reference number ETH19-3718). All progress will be documented on the international prospective register of systematic reviews and Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials databases.

Registration details

Keywords: vasa previa, core outcome set, velamentous cord insertion, stakeholder and patient-reported outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This core outcome set, which is being developed by a multinational group of investigators that comprise the Outcome Reporting in Obstetric Studies project (https://www.obgyn.utoronto.ca/oros-project), is supported by the International Vasa Previa Foundation and will draw input from numerous international organisations to ensure global representation of all stakeholders.

Core outcome set for studies on pregnant women with vasa previa will draw from outcomes reported in all published studies and trial registrations and will not exclude outcomes from studies that are at increased risk-of-bias, in order to obtain the most comprehensive initial list of outcomes.

Increased emphasis is being placed on the qualitative steps of core outcome set development, in order to ensure that patient-reported outcomes and outcomes related to quality of life, resource use and functioning are considered alongside routinely reported clinical outcomes.

Introduction

In approximately 7% of all singleton pregnancies, the umbilical cord inserts close to the edge of the placenta (marginal insertion), and in 1% of cases, a more extreme variation is encountered, wherein the umbilical cord inserts at the apex of the membranous sac (velamentous cord insertion).1 In both these instances, fetal blood vessels could run unprotected outside the umbilical cord, in the membranes surrounding the baby; and when these membranous vessels cross the internal opening of the cervix, preceding the presenting fetal part, the condition is referred to as vasa previa.1 2 Spontaneous or artificial rupture of the membranes around the time of childbirth could result in a rupture of these vessels, putting the baby at risk of severe blood loss, hypotension, anaemia and death by exsanguination. Vasa previa is believed to affect one in 1667–2174 pregnancies (0.46–0.60 per 1000 pregnancies).3 4 If vasa previa is not diagnosed antenatally, and prior to the onset of labour and vaginal delivery, approximately 40%–60% of newborns do not survive.5 6 Early diagnosis and the introduction of clear management plans are imperative for improving outcomes. However, there is no consensus on the optimal approach to antenatal diagnosis as well as various aspects of antenatal and peripartum management.7 As a result, women who have been diagnosed with vasa previa have described feeling ‘like a ticking time bomb’ and expressed the reality of ‘coping with inconsistent information’.8 Preferences of pregnant women with the condition and outcomes that they consider important have not yet been elucidated. Finally, the cost implications to healthcare systems from inpatient versus outpatient management and the use of various diagnostic modalities and management protocols have not been determined.

While these issues can be adequately addressed through well-conducted prospective studies, there is uncertainty with regards to the outcomes that should be measured in these studies and are considered important by pregnant women and other stakeholder groups including healthcare providers, researchers and policymakers. Determining this core set of outcomes that should comprise the bare minimum for inclusion in all further studies is therefore vital. A core outcome set is a set of outcomes that are considered important by those suffering from the condition, their family members and those involved in their care.9

The goal of this study is to gather patients’ and other stakeholders’ input regarding the outcomes important to them, and use this to create a core outcome set for studies on vasa previa which provide researchers with a list of outcomes that must be reported in all future studies, in order to improve its translational value and clinical relevance. This project will reduce bias in outcome reporting, enable meta-analysis of published data to inform decision-making and provide an empiric basis for inclusion of stated outcomes based on input from relevant stakeholders.

Methods and analysis

The protocol for this core outcome set for studies on vasa previa (COVasP) is registered on the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) website. It is guided by the COMET handbook9 and complies with the Core Outcome Set—Standardized Protocol Items statement.10 As with other core outcome sets being developed as part of the University of Toronto’s Outcome Reporting in Obstetric Studies (OROS) project (https://www.obgyn.utoronto.ca/oros-project), COVasP will be developed in five distinct steps, involving qualitative and quantitative research methods, as outlined in figure 1.11 12

Figure 1.

Steps in the development of a core outcome set for studies on vasa previa.

Step 1: Systematic review

A systematic literature review will be undertaken to explore all reported outcomes in published studies involving pregnant women with vasa previa and will generate a preliminary list of outcomes that are deemed important and hence reported by researchers. The protocol for this systematic review, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, is available on the international prospective register of systematic reviews—PROSPERO (CRD42018087837).

Study selection

Five bibliographic databases—Medline, Embase, Cochrane, PubMed (non-Medline and in-process) and Clinicaltrials.gov will be searched from the inception. All interventions and exposures will be included. Randomised or non-randomised studies, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, case series, case reports, qualitative research as well as economic evaluation studies and decision analyses will be included in the search. We will exclude letters to the editor, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts that do not describe clinical outcomes and reviews that do not report on outcomes or contain original research.

Data extraction

Extracted information will include details on study characteristics such as publication year, number of participants, study type, number of included pregnancies, as well as individual and composite outcomes and their definitions, components and measurement instruments when available.

Quality assessment

As the purpose of this review is to identify reported outcomes and not to determine the effectiveness of management strategies, no assessment of the study’s methodological quality will be performed. Similarly, as the aim of this systematic review is to identify all reported outcomes in order to generate a long list of outcomes to inform the development of the core outcome set, and there is no validated tool to assess the quality of outcome reporting, it was decided a priori that the quality of outcome reporting of included studies would not be assessed.

Analysis and presentation of results

The proportion of studies reporting each outcome and the components will be documented. No subgroup or sensitivity analysis is proposed.

Step 2: Stakeholder consultation

In addition to identifying outcomes reported by researchers, we aim to understand what maternal and perinatal outcomes are considered important by women with a diagnosis of vasa previa, their family members, healthcare providers and researchers. Qualitative methodology provides a scope for all relevant stakeholders to discuss their views on important outcomes and contributes to the robustness of core outcome set development by identifying the new outcomes that were not reported in the literature, exploring why the outcomes are considered important and understanding the scope and priority of the outcomes.13 Our systematic literature review found only three qualitative studies on vasa previa; that were conducted with the women,8 midwives14 15 and obstetricians.7 However, these studies were focused on eliciting experiences of patients and midwives, identifying barriers and challenges to care and determining variations in opinions and clinical practice. None specifically focused on identifying the outcomes that could inform the development of COVasP. Hence, we will conduct a descriptive–interpretive qualitative research study16 with the relevant stakeholders in high-income countries.

Inclusion criteria

We will include women who have had a diagnosis of vasa previa (current or previous) and their partners, healthcare providers who have cared for women with a diagnosis of vasa previa and healthcare professionals who have been involved in conducting research or development of a policy/guideline in relation to vasa previa that are above the age of 18 and able to give informed consent and participate in an interview in English language. Women and their partners will be excluded if they (or their partners) had been diagnosed with vasa previa that was not confirmed at a later stage during pregnancy or birth.

Sampling

Women and their partners will be recruited through an established partnership with the International Vasa Previa Foundation (IVPF) (http://vasaprevia.com). The IVPF is an all-volunteer charity created to promote awareness and provide support and advocacy to the general public and professionals regarding vasa previa. In 2018, the IVPF sent out an ‘Expression of Interest’ email to their members which was also shared on social media in relevant peer-support groups as a means of recruitment. To ensure that the views of women with different experiences and backgrounds are represented, specific criteria (age, type of conception, time of diagnosis and country where care was received) will be selected to provide maximum variation sampling as outlined in table 1.13 In addition to the categories outlined in the table, it is hoped that recruiting patients through the IVPF, known contacts and other channels will enable us to access representatives of the following groups (a) those currently pregnancy with a confirmed diagnosis of vasa previa, (b) those who have had pregnancies that resulted in live births and those who resulted in fetal or neonatal death, (c) pregnancies with a complicated and relatively uncomplicated antenatal course, (d) those whose babies suffered serious consequences of prematurity and (e) those who required unplanned/emergency caesarean deliveries versus those whose caesarean deliveries occurred as scheduled. Healthcare providers and researchers will be recruited through email using a study flyer, via contact lists assembled by the study investigators. As is the norm with qualitative research, the exact sample size will be determined once data collection and analysis are commenced.17 Based on the interviews, we have conducted with patients and healthcare professionals in this area, wherein data saturation was attained after the conduct of 14–20 interviews, we anticipate that we will conduct approximately 20 patient interviews and 10–12 interviews with clinicians/researchers until data saturation is reached and no new outcomes are identified in two successive interviews.

Table 1.

Sampling matrix for purposive sampling of women with a history of vasa previa

| Criteria | Target number of participants |

| Method of conception | |

| In vitro fertilisation | 3–5 |

| Spontaneous conception | 10–12 |

| Pregnancy affected by vasa previa | |

| <5 years ago | 6–8 |

| >5 years ago | 6–8 |

| Time of diagnosis of vasa previa | |

| During pregnancy | 10–12 |

| During labour and childbirth | 3–5 |

| Continent | |

| North America | 6–8 |

| Europe | 6–8 |

| Australasia | 6–8 |

| Africa | 1–3 |

| South and Central America | 2–3 |

| Target total | 20 |

Consent

Information regarding the aims of the study and the process of interview will be provided to interested individuals in writing by means of a participant information sheet, highlighting that participation is voluntary. Individuals will be given an opportunity to contact the researchers to receive more information before they make an informed consent to participate in an interview. Only individuals who provide written and/or verbal consent will be interviewed.

Data collection

All interviews will be conducted online or over the phone. On commencement of the interview, the interviewer will confirm that the participant has read the participant information sheet and consent form and obtain verbal consent. The interviewer will then request certain demographic details, which the participants may or may not choose to answer. Demographic details will vary slightly depending on stakeholder group but include: age, occupation, education, ethnicity and descriptions of their experiences with vasa previa or number of years working with this population, as appropriate. After a brief introduction, and providing a description of the project and explanation of what constitutes health outcomes, the interview will commence. The interviews are designed to be semi structured and conversational using a topic guide (Online supplementary file 1). The goal is to ensure that the participant feels comfortable sharing their views and experience while ultimately eliciting health outcomes important to the participants who can then further inform our core outcome set development. During the reflective and iterative process of data collection and analysis, the topic guide may be refined and/or expanded to include the issues raised by earlier participants. One experienced qualitative researcher will conduct all the interviews by telephone or online. The interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

bmjopen-2019-034018supp001.pdf (73.1KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Thematic data analysis18 taking a descriptive interpretive approach19 will start after the first interview. The data will be imported into NVivo V.12 software, which will assist with data management and analysis. Transcripts will be read and coded by a qualitative researcher (NJ) who conducted the interviews. The codes, emerging categories and the related quotes will be discussed with the research team, that includes at least one physician that cares for pregnant women with vasa previa, to reach agreement. Information and outcomes obtained through this qualitative data analysis will be used to develop a list of outcomes deemed important by the participants, which will inform the subsequent Delphi study.

Step 3: Delphi methodology

Steps 1 and 2 generate a long list of outcomes considered important by researchers, women and other stakeholders involved in their care. The Delphi process that follows, is designed to achieve convergence of opinion on these outcomes, in an iterative and sequential manner.20 For this step, we will identify four groups of participants: (1) women, family members and patient advocates or representatives, (2) healthcare providers, (3) researchers, epidemiologists/methodologists and core outcome set developers and (4) other stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in the care of pregnant women such as administrators, guideline developers and policymakers. These groups represent all stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in the care of pregnancies affected by vasa previa. The Delphi survey will be developed by grouping the long list of outcomes (obtained through steps 1 and 2) into five core outcome areas—mortality, morbidity (clinical/physiological), life-impact (functioning), resource-use and adverse events—based on a published taxonomy.21 Lay-language summaries will appear alongside complex medical outcomes. The survey will be piloted with at least 10 people including one person from each stakeholder group. Since we will be using a familiar software, retaining all outcomes obtained through steps 1 and 2, and using prepiloted lay-language summaries for common obstetric and neonatal outcomes developed by the OROS project,11 12 22 the only purpose of piloting the survey is to ensure that representatives of all stakeholder groups have an opportunity to comment on content unique to COVasP. We believe that a sample of 10 people to be sufficient for this step. After piloting, the survey will be made available online (through links on social media) and widely distributed through identified listservers of relevant organisations, including but not restricted to the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (30 members), the Global Obstetric Network (237 members), Core Outcomes in Women’s and Newborn Health (CrOWN) initiative (77 members), corresponding authors of publications on vasa previa included in a recent systematic review,23 IVPF, United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System (https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/ukoss), UK Vasa Praevia Raising Awareness Trust (http://vasapraevia.co.uk), Australasian Maternity Outcomes Surveillance System (https://www.amoss.com.au), Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (https://www.psanz.com.au) and Vasa Praevia Support and Awareness Ireland (https://www.facebook.com/vasapraeviasupportandawarenessIreland). We will aim to recruit at least 25 individuals from each stakeholder group to ensure an appropriate degree of representation. An online approach using DelphiManager software will be employed, to ensure privacy, feasibility, cost effectiveness and reliability, while facilitating global representation.9 On signing an online consent form and completing a brief demographic questionnaire, participants will be required to score each outcome on a 9-point Likert scale based on its perceived degree of importance. Scores of 1–3 will be considered as ‘not essential’; 4–6, ‘important but not critical’ and 7–9, ‘critically important for inclusion’.9 Participants will also be presented with a text box for them to enter any outcomes they deem important, which might not have been included in the list provided.

Analysis

For each outcome, scores will be plotted as histograms, stratified by the each participant’s self-reported group, as follows: (a) patients and patient advocates, (b) clinicians and (c) researchers. All new outcomes emerging from round 1, if deemed by COVasP investigators as distinct from those presented, will be included into the second round. On completion of first-round analysis, an invitation will be sent out to all members requesting participation in the second round. Each member scoring outcomes in the second round will have access to the histograms presenting first-round scores stratified by the participant group, to enable participants to decide on whether they would like to retain their original score, or modify it. Email reminders will be sent out to ensure that at least 85% of respondents complete both surveys, to prevent attrition bias. Each participant will be asked whether they would like to and be able to attend a face-to-face consensus meeting, details of which will be determined, by this juncture.

Missing data and attrition

Participants will be given clear outlined expectations of timelines and a 6-week window to complete each round of the survey. Should the response rate not achieve 80%, a level deemed acceptable by published recommendations,9 additional interventions will be implemented, guided by measures adopted by other core outcome set developers. Telephone calls, emails, personal reminders and extension of the survey deadlines may be used to improve the response rate. Any feedback after the first round regarding obstacles when completing the survey in its entirety will be noted and addressed before the second round.

Step 4: Consensus meeting

All outcomes that are deemed ‘critically important for inclusion’ (scores 7–9 on the second round of the Delphi survey) by 70% of all stakeholders will be included in the final core outcome set. This includes intermediary and surrogate outcomes. In addition, in order to ensure that the patient perspective is reflected, we will also retain and include in the final core outcome set, outcomes that are scored 7–9 by 70% of patients alone. Outcomes assigned scores 1–3 by >70% of all participants will be discarded. Outcomes assigned scores of 4–6 (important but not critical) by >70% of stakeholders will be further discussed at a face-to-face consensus meeting, which will use a structured variation of a small-group discussion called the nominal group technique.24 At the consensus meeting, participants will be first asked to independently decide whether each of these outcomes in question should be included in the core outcome set or not. This will be followed by small-group discussions, wherein members express their understanding of the logic and the relative importance of each of these ‘important but not critical’ outcomes and debate whether they should be included in the final core outcome set or not. The final list of outcomes deemed as critical to include in the final core outcome set, presented by each small group, will be reflective of the group’s overall preferences, and through mutual consensus will constitute the final core outcome set. The advantages of using nominal group technique is that the process prevents the domination of the discussion by a single person, encourages all group members to participate and results in a set of recommendations that represent the group’s preferences.

This consensus meeting will occur over a half day and will be conducted in keeping with the specifications laid out by the Evaluation Research Team at the Centre for Disease Control,24 and the entire process will be audio-recorded. Groups developing core outcome sets of obstetric conditions have included between 14 and 29 participants in this step. Without prespecifying a number, we will aim to ensure equal representation of each stakeholder group and schedule this face-to-face meeting to coincide with an international obstetrics conference, in order to ensure global participation of representatives of various stakeholder groups. However, we acknowledge that this might be difficult to organise, and therefore, in the interest of feasibility, might have to settle for organising this at the time of a local meeting, with most stakeholder representatives from within Canada. Since international representation will already have been sought through the Delphi survey, and on account of the cautious approach to eliminating outcomes described above, we do not believe this will compromise study integrity.

The OROS project, under whose initiative, COVasP is being developed, endeavours to achieve a balance between standardisation and comprehensiveness of outcome reporting. While the development of a core outcome set will address the former, the latter is important to ensure inclusion of maternal and fetal outcomes representing all core outcome areas,21 which include mortality/survival, clinical/physiological, life-impact/functioning, resource use and adverse events. There will, therefore, be no limit on the final number of outcomes constituting COVasP. As described in protocols for other core outcome sets being developed by the OROS group, all outcomes identified through the above process, will be presented in tabular form, separating maternal from fetal/neonatal outcomes, each stratified by the five main core outcome areas, and an online supplementary table highlighting all outcomes, their Delphi scores and the stages at which they were excluded will also be presented, for greater transparency.12

Step 5: Mmeasuring/defining core outcomes

On selection of a final list of core outcomes, we will employ the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments to assess measurement tools/definitions for included outcomes based on four criteria: validity, responsiveness, reliability and interpretability.25 We will begin the process by listing measurement instruments and/or definitions for outcomes where universal agreement exists. For outcomes where there is a lack of agreement on measurement instruments or definitions, we will conduct systematic reviews to determine all currently used instruments and definitions. This will be followed by Delphi surveys involving relevant stakeholder groups as required, to determine the most appropriate definition or measurement instrument for each identified core outcome where systematic reviews are inconclusive.26 Details of this process will depend on the final list of outcomes and are beyond the scope of this protocol.

Patient and public involvement

Although the steps of developing a core outcome set are standardised, we will involve patients and other stakeholders to participate in steps 2–4, through interviews, the Delphi survey and a consensus meeting. The purpose of their involvement is to determine what outcomes related to vasa previa are most important to them. The design of the study encourages stakeholders to consider outcomes related to domains such as functioning, resource use, satisfaction, compliance, healthcare delivery and mental health concerns in addition to the clinical and physiological outcomes most commonly reported in research studies. We have taken steps to ensure that these outcomes considered important by patients are represented in the final core outcome set. We aim to involve patients in ensuring that COVasP is disseminated widely through the IVPF webpage and also through social media, in addition to ensuring knowledge translation to clinicians and researchers. The findings of each step of COVasP development will be published on the OROS website (https://www.obgyn.utoronto.ca/oros-project), enabling ongoing feedback from patients and the public.

Discussion

COVasP aims to provide researchers and clinicians with a systematically derived list of outcomes, incorporating preferences of patients and other relevant stakeholders, which will form the minimum standard required to be collected, measured and recorded as a baseline in all clinical studies on vasa previa. Input from various stakeholder groups will enhance the quality and relevance of future studies on vasa previa and go a long way in improving outcomes that are considered most important by those that are affected by this rare but serious obstetric condition.

Ethics and dissemination

This study as well as consent forms for stakeholder participation have received approval from the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board (REB number 18-0173-E) on 05 September 2018 and the Human Research Ethics Committee at The University of Technology Sydney, Australia on 30 July 2019 (UTS HREC reference number ETH19-3718). The findings of the systematic review, patient interviews and final COS will be published in open-access journals and presented at national and international obstetrics and maternal–fetal medicine conferences. All progress will be documented on the PROSPERO, COMET and CROWN databases and made freely available through the IVPF webpage. Corresponding authors of studies included in the systematic review and participants in the qualitative interviews, Delphi surveys and consensus group meetings will be provided with a copy of all publications related to COVasP, to encourage its dissemination and use in future studies on the topic.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @singingOB

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. The affiliations for author Nasrin Javid have been updated.

Contributors: RD conceived the idea, has experience with mixed-methods study design and development of core outcome sets and is the principal investigator and the founder of the Outcome Reporting in Obstetric Studies project. NJ designed the qualitative research components of the study. LV, CH and MS helped with drafting various aspects of the manuscript. JK is a maternal–fetal medicine physician with clinical expertise in the management of vasa previa. MK, ND and NJ represent the International Vasa Previa Foundation. NJ, RD, JK, MK and ND secured funding for the study. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: This study is funded by the David Henderson-Smart 2019 Scholarship awarded to Nasrin Javid by the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the International Vasa Previa Foundation (IVPF).

Competing interests: MK and ND are directors and NJ is a member of the International Vasa Previa Foundation that has provided part funding for this project. RD has received speaking honoraria from Ferring, Canada for presentations unrelated to this project.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Baergen R. Manual of pathology of the human placenta. Second ed Boston, MA: Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benirschke K, Burton G, Baergen R. Pathology of the human placenta. Sixth ed Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavalagantharajah S, Villani LA, D’Souza R. Vasa previa and associated risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020:100117 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiter L, Kok N, Limpens J, et al. . Incidence of and risk indicators for vasa praevia: a systematic review. BJOG 2016;123:1278–87. 10.1111/1471-0528.13829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan EA, Javid N, Duncombe G, et al. . Vasa previa diagnosis, clinical practice, and outcomes in Australia. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:591–8. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyelese Y, Catanzarite V, Prefumo F, et al. . Vasa previa: the impact of prenatal diagnosis on outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:937–42. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000123245.48645.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javid N, Hyett JA, Walker SP, et al. . A survey of opinion and practice regarding prenatal diagnosis of vasa previa among obstetricians from Australia and New Zealand. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;144:252–9. 10.1002/ijgo.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javid N, Sullivan EA, Halliday LE, et al. . "Wrapping myself in cotton wool": Australian women's experience of being diagnosed with vasa praevia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:318. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. . The comet Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017;18:280. 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. . Core outcome Set-STAndardised protocol items: the COS-STAP statement. Trials 2019;20:116. 10.1186/s13063-019-3230-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dadouch R, Faheim M, Juando-Prats C, et al. . Development of a core outcome set for studies on obesity in pregnant patients (COSSOPP): a study protocol. Trials 2018;19:655. 10.1186/s13063-018-3029-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Souza R, Hall C, Sermer M, et al. . Development of a core outcome set for studies on cardiac disease in pregnancy (COSCarP): a study protocol. Trials 2020;21:300. 10.1186/s13063-020-04233-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, et al. . The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials 2016;17:230. 10.1186/s13063-016-1356-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Javid N, Hyett JA, Homer CS. Providing quality care for women with vasa praevia: challenges and barriers faced by Australian midwives. Midwifery 2019;68:91–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javid N, Hyett JA, Homer CSE. The experience of vasa praevia for Australian midwives: a qualitative study. Women Birth 2019;32:185–92. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott R, Timulak L. Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research : Miles J, Paul G, A Handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. Oxford University Press, 2005: 147–59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health 1997;20:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000393. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, et al. . A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;96:84–92. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King A, D’Souza R, Teshler L NS, et al. . The development of a core outcome set for studies on pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism (COSPVenTE): a study protocol. BMJ Open 2020. [This paper has been accepted by BMJ Open. Please add appropriate reference details]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villani LA, Pavalagantharajah S, D’Souza R. Variations in reported outcomes in studies on vasa previa: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020:100116 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC Gaining consensus among stakeholders through the nominal group technique. evaluation Briefs (7): United States department of health and human services. centers for disease control and prevention, 2018. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief7.pdf

- 25.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. . The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010;19:539–49. 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prinsen CAC, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. . How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a "Core Outcome Set" - a practical guideline. Trials 2016;17:449. 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034018supp001.pdf (73.1KB, pdf)