Abstract

Purpose

Inflammation is important in stroke. Anti-inflammatory therapy reduces vascular events in coronary patients. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) identifies plaque inflammation-related metabolism. However, long-term prospective cohort studies investigating the association between carotid plaque inflammation, identified on 18F-FDG PET and the risk of recurrent vascular events, have not yet been undertaken in patients with stroke.

Participants

The Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid disease (BIOVASC) study and Dublin Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (DUCASS) are two prospective multicentred observational cohort studies, employing near-identical methodologies, which recruited 285 patients between 2008 and 2016 with non-severe stroke/transient ischaemic attack and ipsilateral carotid stenosis (50%–99%). Patients underwent coregistered carotid 18F-FDG PET/CT angiography and phlebotomy for measurement of inflammatory cytokines. Plaque 18F-FDG-uptake is expressed as maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) and tissue-to-background ratio. The BIOVASC-Late study is a follow-up study (median 7 years) of patients recruited to the DUCASS/BIOVASC cohorts.

Findings to date

We have reported that 18F-FDG-uptake in atherosclerotic plaques of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis predicts early recurrent stroke, independent of luminal narrowing. The incorporation of 18F-FDG plaque uptake into a clinical prediction model also improves discrimination of early recurrent stroke, when compared with risk stratification by luminal stenosis alone. However, the relationship between 18F-FDG-uptake and late vascular events has not been investigated to date.

Future plans

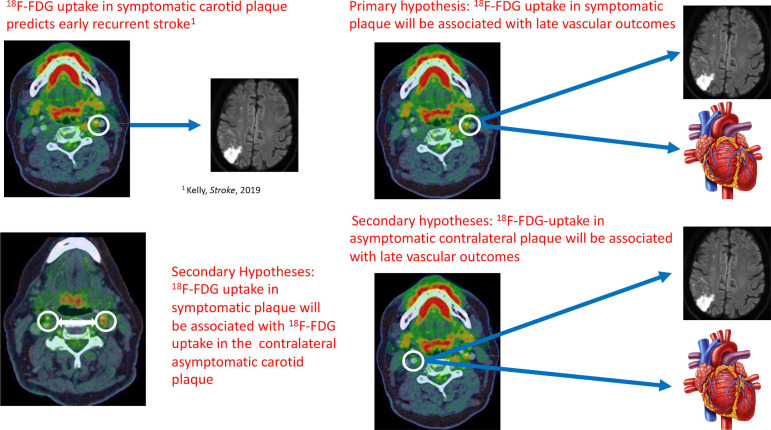

The primary aim of BIOVASC-Late is to investigate the association between SUVmax in symptomatic ‘culprit’ carotid plaque (as a marker of systemic inflammatory atherosclerosis) and the composite outcome of any late major vascular event (recurrent ischaemic stroke, coronary event or vascular death). Secondary aims are to investigate associations between: (1) SUVmax in symptomatic plaque, and individual vascular endpoints (2) SUVmax in asymptomatic contralateral carotid plaque and SUVmax in ipsilateral symptomatic plaque (3) SUVmax in asymptomatic carotid plaque and major vascular events (4) inflammatory cytokines and vascular events.

Keywords: stroke, cardiovascular imaging, preventive medicine, adult neurology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid-Late (BIOVASC-Late) is the first study to investigate the prognostic utility of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT angiography (CTA) for late outcome vascular events in patients with stroke.

Long-term data on the prognostic role of imaging/blood biomarkers of inflammation will help inform the need for future randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory therapies for secondary prevention in patients with stroke.

The study has a fixed sample size, which means that the analyses for some secondary outcomes may be underpowered.

PET-CTA has certain limitations as a plaque-imaging modality, primarily its limited spatial resolution, high monetary costs, radiation exposure and inability to identify potentially relevant plaque features (eg, intraplaque haemorrhage or surface ulceration), which have been associated with stroke recurrence.

The majority of patients enrolled in this study are older males. This may limit the generalisability of its findings.

Introduction

Stroke remains a leading cause of death, disability and dementia worldwide.1 Despite modern secondary prevention therapy, the risk of recurrent major vascular events after ischaemic stroke is in the region of 25%–30% over 5 years.2 There is an urgent and growing need for new therapeutic targets for secondary prevention.

Clinicopathological studies implicate inflammation in plaque destabilisation and stroke pathogenesis.3–5 Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with coronary disease have recently been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent vascular events,6–8 but not all studies have replicated these findings.9 The Low-Dose Colchicine (LoDoCO) and Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT) trials have both shown that colchicine reduces the risk of major vascular events in patients with coronary disease.6 7 The Canakinumab. Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS) trial also showed that interleukin-1β (IL-1β) inhibition with canakinumab reduced the risk of vascular events in patients with stable coronary disease.8 The Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT) trial compared low-dose methotrexate to placebo in patients with stable coronary disease but no benefit was shown.9 COlchicine for preventioN of Vascular Inflammation in Non-Cardioembolic stroke trial (CONVINCE) is the first prevention trial to investigate whether anti-inflammatory therapy might reduce the risk of vascular events in stroke patients and recruitment is currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02898610).

However, the prognostic role of inflammatory biomarkers in stroke patients is uncertain. Better data are needed to strengthen the rationale for future prevention trials of anti-inflammatory therapy in stroke survivors. Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid (BIOVASC and Dublin Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (DUCASS) are two prospective multicentred cohort studies of patients with symptomatic carotid disease, which employed near-identical methodologies, and examined the relationship between blood and imaging biomarkers of inflammation and the risk of early recurrent stroke. The BIOVASC-Late study is a late follow-up study (range 3–12 years, median 7 years) of patients recruited to the DUCASS/BIOVASC cohorts.

Prognostic role of imaging biomarkers of vascular inflammation

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) is a validated technique for non-invasive imaging of inflammation-related plaque metabolism and is associated with histological evidence of inflammation in resected human carotid plaque specimens.10 11 18F-FDG uptake in one artery is strongly associated with 18F-FDG uptake in neighbouring arteries, suggesting that plaque inflammation measured by PET might be a surrogate marker of a systemic inflammatory atherosclerotic plaque burden.12 Several large studies have shown that 18F-FDG arterial uptake in patients without a history of vascular disease is associated with future cardiovascular events independent of other vascular risk factors.13 14 However, the association between atherosclerotic plaque inflammation measured by 18F-FDG-PET, in recently symptomatic patients with stroke, and the risk of late major vascular events has heretofore not been studied.

Prognostic role of circulating blood biomarkers of inflammation

Circulating blood biomarkers of inflammation, such as C reactive Protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) are associated with first stroke in patients without a history of vascular disease.15–17 However, studies investigating the prognostic role of inflammatory cytokines in stroke survivors have shown conflicting results and require further investigation.18–23 Furthermore, few data exist on the cross-sectional association between circulating inflammatory cytokines and carotid plaque inflammation-related hypermetabolism (measured by 18F-FDG PET) in recently symptomatic patients with stroke.

Aims

The primary aim of BIOVASC-Late is to investigate the association between 18F-FDG uptake in carotid plaques of recently symptomatic ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA) patients and the risk of any late major cardiovascular event defined as a composite of non-fatal ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina requiring hospitalisation, non-fatal cardiac arrest or vascular death (seefigure 1), occurring 30 days after the index event.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the study hypotheses.

Our secondary aims are:

To investigate the association between 18F-FDG uptake in ipsilateral (‘culprit’) plaque in ischaemic stroke/TIA patients and the risk of the individual components of the primary endpoint.

To investigate the cross-sectional association between 18F-FDG uptake in the ipsilateral (‘culprit’) carotid artery of ischaemic stroke/TIA patients and 18F-FDG uptake in the contralateral asymptomatic (‘non-culprit’) carotid artery.

To investigate the association between 18F-FDG uptake in the asymptomatic contralateral (‘non-culprit’) carotid artery and the risk of the composite vascular outcome.

To investigate the association between inflammatory cytokines measured acutely, at the time of the index event, and the risk of late vascular events.

Exploratory aims will include:

To investigate the associations between:

Inflammatory cytokines, measured acutely, and 18F-FDG uptake in ipsilateral symptomatic and contralateral asymptomatic carotid artery.

Inflammatory cytokines, measured acutely, with levels of inflammatory cytokines measured at late follow-up.

18F-FDG uptake in symptomatic ‘culprit’ carotid plaque in ischaemic stroke/TIA patients and outcome events due peripheral arterial disease.

18F-FDG uptake in symptomatic ‘culprit’ carotid plaque and late-outcome ipsilateral ischaemic stroke.

Cohort description

DUCASS: eligibility

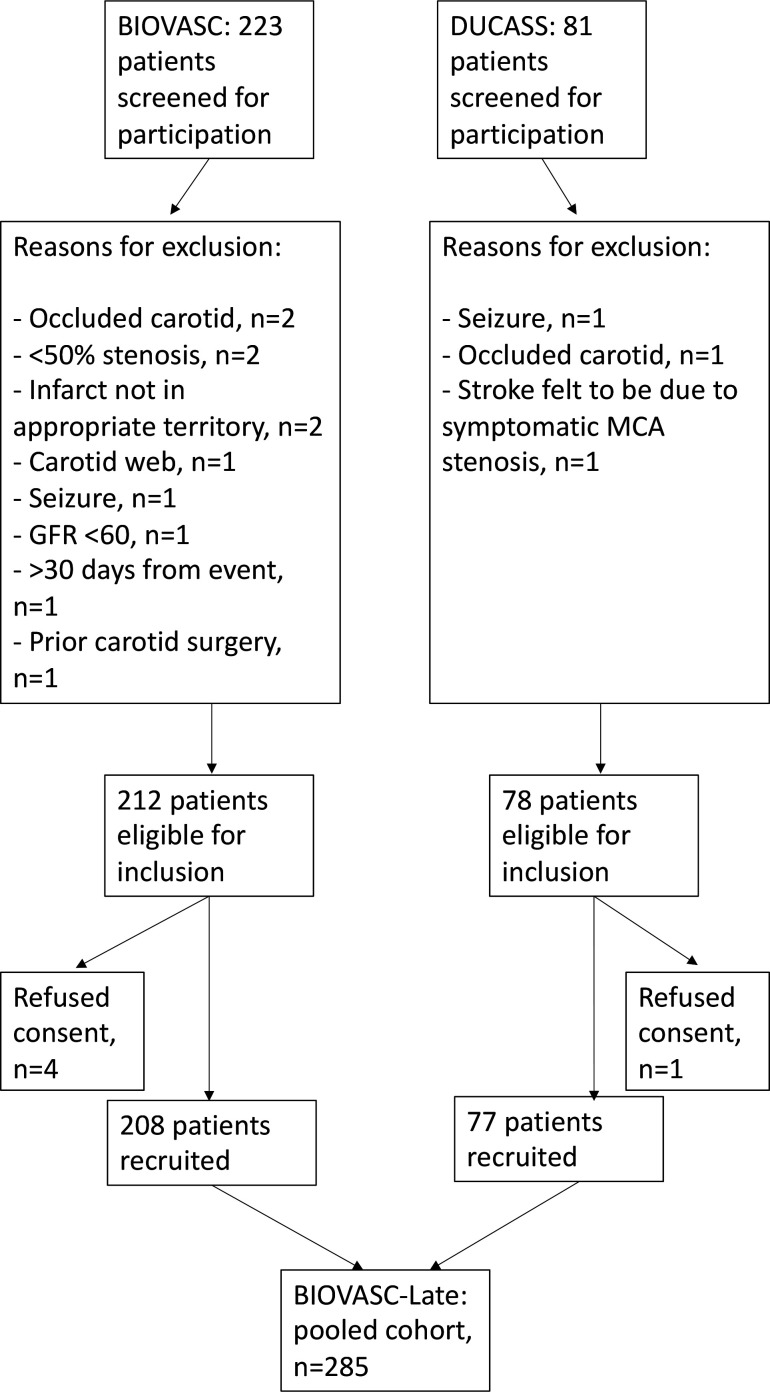

DUCASS is a multicentred prospective observational cohort study, which recruited 77 patients from 2008 to 2012 from four centres in Ireland. Inclusion criteria were: recent (≤14 days) TIA, non-severe stroke (modified Rankin Scale (mRS) ≤3) or retinal artery embolism; ipsilateral non-occlusive internal carotid stenosis (≥50% luminal narrowing) identified by duplex ultrasound (confirmed by CT angiography (CTA) and/or MR angiography). Exclusion criteria were: pregnancy; age <50 years; active malignancy; prior neck irradiation; prior ipsilateral carotid endarterectomy/stenting; ipsilateral carotid occlusion; dementia haemodynamic stroke/TIA due to carotid near-occlusion, and significant renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min) or other contraindication to contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. Patients were followed up at at 7, 30, 90 days, 1 and 2 years, either by telephone contact or by in-person assessment.

BIOVASC: eligibility

BIOVASC is a multicentre prospective cohort study conducted in 10 centres in Ireland (six sites), Barcelona, Paris, Calgary, and Singapore (one site each), which recruited 208 patients from 2012 to 2016. Eligibility criteria were identical to DUCASS, apart from an extension of the time-window from presenting event to enrolment to 30 days. Patients were initially followed up at 7, 30, 90 days and 1 year, either by telephone contact or by in-person assessment. A flow diagram illustrating the screening and recruitment process for both studies are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram illustrating study screening, eligibility and enrolment. BIOVASC, Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid; DUCASS, Dublin Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. MCA, middle cerebral artery; GFR, glomelular filtration rate.

Baseline study procedures: covariates

The following information was recorded at recruitment: patient demographics, qualifying event, National Institute for Health Stroke Scale score, mRS, ABCD2 score, medications at time of index event and recruitment, history of smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease and prior stroke or TIA. Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus were each defined according to self-reported history, medical record documentation, new diagnosis at recruitment or if the patient was taking anti-hypertensives, lipid-lowering or glucose-lowering medications. Atrial fibrillation was defined according to self-reported history, medical record documentation or if newly diagnosed during hospital admission for the index event. Peripheral arterial disease was defined as medical record or self-reported history of intermittent claudication, abdominal artery aneurysm, or prior peripheral/extracranial revascularisation procedure. Coronary heart disease was defined as medical record or self-reported history of MI, angina or coronary revascularisation.

Baseline study procedures: phlebotomy

In both studies, patients underwent phlebotomy within 72 hours of enrolment. Serum and plasma samples were transferred to a central laboratory and centrifuged at 1600 revolutions per minute for 20 min as soon as possible (target <2 hours) and stored at −80°C.

Baseline study procedures: PET-CT

Standardisation and quality assurance of PET-CT imaging were achieved by three methods: internal PET scanner quality assurance checks using standard phantoms24 25; adherence to a prespecified standardised protocol and sensitivity analyses to verify the consistency of results across participating centres. 18F-FDG PET-CTA was performed within 7 days (<14 days in DUCASS) of study entry, after a minimum 6 hour fast. PET scans were not performed if pre-PET blood glucose exceeded 10 mmol/L. We administered 320 MBq of 18F-FDG 2 hours before image acquisition to allow sufficient image quality and adequate time for arterial FDG-uptake. This approach is in line with recommendations by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM).26 The uptake phase was standardised with the patient resting. PET images were acquired in a three-dimensional mode in two-bed positions for 10 min each. After PET, a low-dose CT for attenuation correction was performed using the same scanner followed by the aortic arch to skull-base carotid CTA using contrast-bolus tracking. The PET-CT image acquisition parameters were near-identical in the BIOVASC and DUCASS studies.

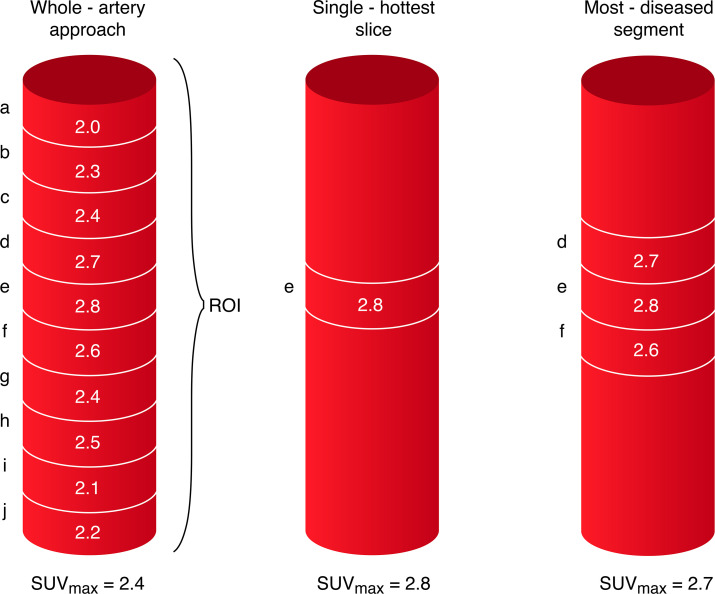

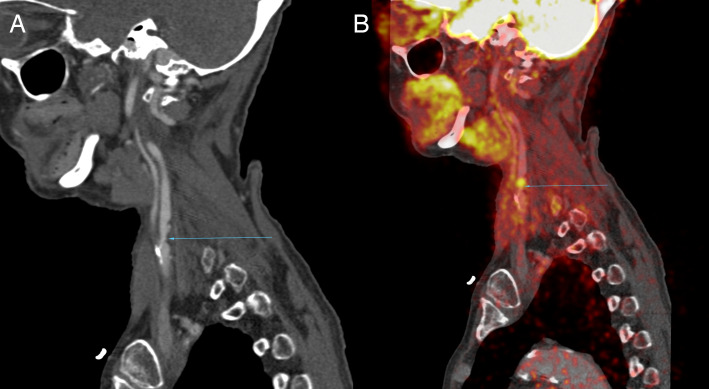

Before commencing the analysis, semiautomated coregistration of PET and CT images are performed, the details of which have been described elsewhere.25 For symptomatic carotid arteries 18F-FDG activity in 10 regions of interest are defined relative to the slice of maximal stenosis. In the asymptomatic contralateral carotid artery, 30 regions of interest are identified extending superiorly from the carotid bifurcation. 18F-FDG activity is quantified using standardised uptake values (SUV (g/mL)=measured uptake (MBq/mL)/injected dose (MBq) per patient weight [g]). We define the single ‘hottest slice’ (SHS) as the axial slice with maximal SUV (SUVmax) and the most diseased segment (MDS) as the SHS plus the adjacent proximal and distal axial slices, corresponding to vessel area 3 mm in length (see figures 3, 4A, B).27 All images are centrally analysed by a single trained reader. Intrarater reliability assessment showed excellent agreement (intraclass correlation α=0.814, p<0.001).25 For all analyses relating to plaque inflammation-related metabolism, SUVmax will be considered as the primary exposure variable of interest. As part of a sensitivity analysis, a whole-artery approach to calculating SUVmax will be used to assess the relationship between target vessel inflammation in asymptomatic carotid arteries and risk of the composite outcome. Furthermore, the analyses will be repeated using tissue-to-background-ratio (TBR) as an alternative metric of 18F-FDG uptake. The TBRmax is calculated as the ratio of SUVmax and venous blood pool mean SUVmean to correct for blood-pool uptake. These additional analyses will be performed in keeping with EANM guidelines.26

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of 18-F-FDG PET-CTA image acquisition. Ten regions of interest (ROI) are defined as 1 mm thick slices above and below the area of maximal luminal narrowing in the symptomatic carotid artery. Thirty ROI are defined superior to the carotid bifurcation in the contralateral asymptomatic carotid artery (not shown). 18-F-FDG uptake in the vessel wall is quantified using (SUV (g/mL)) with the highest uptake in each slice defined as the SUVmax. The whole-artery approach to measuring vessel inflammation calculates the average of the SUVmax across the ROI(a+b+c+d+e+f+g+h+i+j/10). The SHS is defined as the axial slice with highest SUVmax(slice ‘e’). 18F-FDG-uptake in the most-diseased-segment is taken as the average of the SUVmax across three slices defined relative to the SHS (d+e+ f/3). 18F-FDG PET, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; CTA, CT angiography; SUVmax, maximum standardised uptake value.

Figure 4.

(A) CTA shows a moderate (~50%) stenosis of the left proximal internal carotid artery (blue arrow) in a recently symptomatic stroke patient presenting with right sided weakness and dysphasia. (B) Co-registered 18F-FDG PET-CTA of same patient shows increased focal FDG-uptake in the region of the carotid plaque. 18F-FDG PET, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; CTA, CT angiography.

Our rationale for using SUVmax in the SHS and MDS as the primary exposure of interest is to ensure that focal areas of vessel wall inflammation are identified and not ‘averaged-out’ by a whole-artery approach. The recent guidelines have outlined the strengths and limitations of both approaches. SUVmax measurements in plaques reflect the part of the lesion with the highest FDG uptake. However, the level of noise in the image and the adjacent blood signal (spill-in of adjacent activity related to partial volume effects) can influence measurements of SUVmax. The use of TBR over SUV has been favoured by some due to its reliability across imaging acquisition times and tracer circulation times, while other studies have shown no additional benefit with blood background correction.26 28 Given the uncertainty we have chosen to evaluate both methods to ensure consistency of our findings.

BIOVASC-Late: study design and procedures

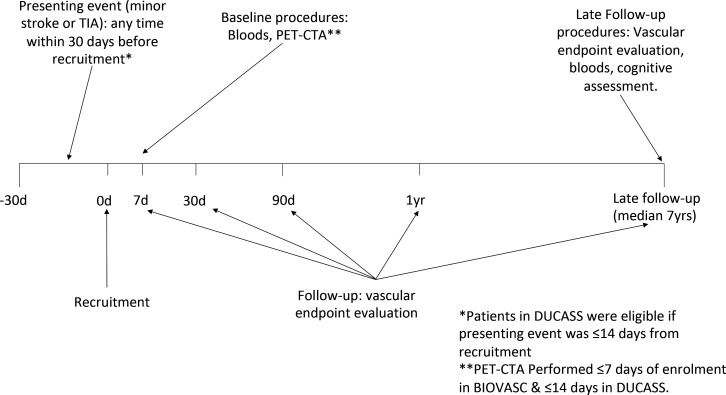

The BIOVASC-Late study is an extended follow-up study of patients recruited to the DUCASS and BIOVASC cohorts. Participating centres will be limited to the Irish study sites. Patients recruited to the original studies will be invited to participate in a single in-person follow-up assessment (see figure 5). Consenting patients and/or their caregivers will undergo a standardised interview for any symptoms suspicious for recurrent stroke/TIA, unstable angina, MI, non-fatal cardiac arrest or peripheral arterial disease. Functional outcome will be assessed using the Barthel index and the mRS (using a validated standardised algorithm).29 30 Patients who have died since last follow-up will have outcome events recorded by multiple-overlapping methods including contact with the participant’s general practitioner, review of hospital records and death certification. Surviving patients will also undergo a comprehensive cognitive evaluation as part of a cognitive substudy, the protocol of which will be described separately.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of timeline of BIOVASC-Late study. BIOVASC, Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid; CTA, CT angiography; DUCASS, Dublin Carotid Atherosclerosis Study; PET, positron emission tomography; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Patients will also undergo late phlebotomy, which will be processed in an identical manner to baseline samples taken at recruitment. Patients will be carefully screened for active infection, inflammatory conditions, active malignancy, recent trauma or surgical procedures (<1 month), and in suspected cases phlebotomy will be deferred, where possible, until such time as the condition has resolved. Baseline and late serum samples will be analysed by a trained laboratory scientist, blinded to baseline clinical data, for circulating blood biomarkers of inflammation. CRP will be analysed in serum by immunoturbidimetric detection using the high-sensitive MULTIGENT CRP Vario assay (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA). IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL10, IL-12p70, interferon-γ, tumour necrosis factor-α, will be assessed by electro-chemi-luminescent detection, using a commercially available 96 well-plate Human Pro-Inflammatory multi-Plex Ultra Sensitive Kit (Merck Sharp & Dohme, Maryland, USA). MCP-1 will be analysed using an ELISA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA).

Outcome definitions

Suspected outcome events will be confirmed by in-person evaluation by a study investigator and by medical record review. Any suspected stroke or cardiovascular outcome event will then be independently adjudicated by the principal investigator (PK), blinded to baseline data.

Recurrent stroke will be defined as a sudden-onset worsened neurological deficit lasting greater than 24 hours occurring after 18F-FDG PET-CTA. Gradual progression of an existing neurological deficit, sub-clinical detection of new infarction on neuroimaging, or deterioration due to cerebral oedema, large haemorrhagic transformation, seizure, metabolic disturbance or other illness will be excluded. Only recurrent strokes unrelated to a revascularisation procedure (defined as before or later than 24 hours of carotid revascularisation) will be defined as outcomes. MI will be defined according to the third universal definition.31 Unstable angina requiring hospitalisation will be defined according to consensus criteria outlined by the Standardised Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative and the US Food and Drug Administration.32 Non-fatal cardiac arrest will be defined as recovery from sudden collapse, with ECG rhythm-strip verified cardiac asystole, ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Vascular death will be defined as sudden cardiac death, fatal MI, fatal ischaemic stroke, or death due to mesenteric ischaemia or peripheral arterial disease. Peripheral arterial endpoints will include acute limb ischaemia, peripheral arterial revascularisation, mesenteric ischaemia or peripheral amputation for vascular causes. Acute limb ischaemia will refer to hospitalisation for a rapid or sudden decrease in limb perfusion and either: (1) a new pulse deficit, rest pain, pallor, paraesthesia or paralysis; or (2) confirmation of arterial obstruction by limb haemodynamics (ankle or toe pressure), imaging, intraoperative findings or pathological evaluation. Peripheral revascularisation will be defined as any peripheral procedure performed to treat limb ischaemia or prevent major limb ischaemic events and will include endovascular or surgical revascularisation as well as amputation, but will not include carotid artery revascularisation. Mesenteric ischaemia will be defined as imaging or autopsy evidence of small or large bowel ischaemic infarction.

Baseline clinical characteristics of study participants

The baseline clinical characteristics of DUCASS and BIOVASC, as well as the pooled dataset of BIOVASC-Late, are outlined in table 1. Baseline characteristics of both cohorts were similar, apart from a higher rate of atrial fibrillation and a slightly greater degree of stroke-severity in DUCASS. A greater proportion of patients in BIOVASC were taking antiplatelet medications and a lower proportion taking anti-coagulants at the time of recruitment, compared with patients in DUCASS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of BIOVASC and DUCASS study cohorts

| BIOVASC-Late pooled data (n=285) | DUCASS (n=77) | BIOVASC (n=208) | P value | |

| Demographics (n=285) | ||||

| Age | 69.8 (9.8) | 70.6 (10.3) | 69.5 (9.6) | 0.4 |

| Sex, male | 68.4 (195) | 68.8% (53) | 68.3 (142) | 0.93 |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 100 (285) | 100 (77) | 100 (208) | 1 |

| Index event (n=285) | ||||

| TIA | 39.6 (113) | 40.3 (31) | 39.4 (82) | 0.83 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 43.9 (125) | 45.4 (35) | 43.3 (90) | |

| Retinal embolism | 16.5 (47) | 14.3 (11) | 17.3 (36) | |

| Smoking status (n=284) | ||||

| Current | 40.8 (116) | 39 (30) | 41.6 (86) | 0.88 |

| Previous | 40.5 (115) | 42.9 (33) | 39.6 (82) | |

| Never | 18.7 (53) | 18.2 (14) | 18.8 (39) | |

| Other risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension (n=284) | 88 (250) | 90.9 (70) | 87 (180) | 0.36 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n=284) | 16.9 (48) | 19.5 (15) | 15.9 (33) | 0.48 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (n=285) | 78.6 (224) | 77.9 (60) | 78.8 (164) | 0.87 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n=284) | 14.4 (41) | 23.4 (18) | 11.1 (23) | 0.01 |

| Coronary heart disease (n=284) | 32 (91) | 35.1 (27) | 30.9 (64) | 0.51 |

| Peripheral arterial disease (n=284) | 9.5 (27) | 13 (10) | 8.2 (17) | 0.22 |

| Medications and therapeutic interventions | ||||

| Statin at index event (n=284) | 50 (142) | 45.5 (35) | 51.7 (107) | 0.35 |

| Statin at recruitment (n=284) | 92.6 (263) | 94.8 (73) | 91.8 (190) | 0.39 |

| High-intensity statin at recruitment (n=279) | 63.8 (178) | 63.9 (46) | 63.8 (132) | 0.99 |

| Antiplatelet at index event (n=284) | 46.8 (133) | 50.6 (39) | 45.4 (94) | 0.43 |

| Anti-platelet at recruitment (n=283) | 92.6 (262) | 85.5 (65) | 95.2 (197) | 0.01 |

| Anticoagulant at index event (n=284) | 5.6 (16) | 6.5 (5) | 5.3 (11) | 0.7 |

| Oral anticoagulant at recruitment (n=284) | 8.8 (25) | 16.9 (13) | 5.8 (12) | 0.003 |

| IV tpa (n=284) | 6.7 (19) | 3.9 (3) | 7.7 (16) | 0.25 |

| EVT (n=284) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Carotid endarterectomy (n=284) | 64.1 (182) | 53.3 (41) | 68.1 (141) | 0.02 |

| Carotid stenting (n=284) | 2.5 (7) | 1.3 (1) | 2.9 (6) | 0.44 |

| Stroke severity, median (IQR) | ||||

| NIHSS (n=281) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| Modified Rankin Scale (n=282) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0.002 |

| Stenosis severity (n=285) | ||||

| Moderate | 46.7 (133) | 61 (47) | 41.4 (86) | 0.8* |

| Severe | 43.5 (124) | 28.6 (22) | 49 (102) | |

| Near-occlusion | 9.8 (28) | 10.4 (8) | 9.6 (20) | |

Categorical data expressed as % (number). Continuous data expressed as mean (SD) unless otherwise stated. χ2 test is used for comparing differences in proportions. Two sample t-test is used or the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous data as appropriate. The X2 statistical test for trend was used for comparing proportions in ordered categorical data (>2 groups).

*P value for X2 statistical test for trend.

BIOVASC, Biomarkers Imaging Vulnerable Atherosclerosis in Symptomatic Carotid; DUCASS, Dublin Carotid Atherosclerosis Study; EVT, endovascular therapy; IV tpa, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator; NIHSS, National Institute for Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design of either study. However, since the study was initiated the Stroke Clinical Trials Network Ireland has developed a formal strategy for patient-public involvement and has formally recruited designated patient ambassadors, who will be consulted prior to dissemination of the study’s results to participating patients.

Statistical analysis plan

Clinical characteristics will be compared using t-tests, Mann-Whitney or χ2 tests. Non-parametric tests will be used where data is not normally distributed. The plaque SUVmax will be the exposure variable for hypothesis testing. Bivariate and multivariable Cox regression will be performed to determine factors associated with dichotomous outcomes, associated with 1 g/mL increase in SUVmax in culprit/non-culprit plaque, with censoring at the time of a recurrent vascular event, last follow-up visit or death. Cox proportional hazard regression will be used to estimate the unadjusted HR for SUVmax with time-to-event as the dependent variable. The proportional hazard assumption will be tested by visual examination of survival curves and by the Schoenfeld test. Forward stepwise multivariable Cox regression will be used to estimate the adjusted HR for the biomarker level after adjusting for potential confounding variables. Independent variables will be included in the model based on a p≤0.05 on bivariate analysis or a known clinical rationale for association with stroke recurrence (eg, age, hypertension, statin use, smoking) regardless of its association on bivariate analysis. The rationale for this approach is to fully adjust for any potential confounders. Associations between continuous variables will be analysed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient for biomarkers with a normal distribution and Spearman’s correlation test for biomarkers with a non-normal distribution. Simple linear regression analysis will be used to explore the associations between SUVmax (outcome variable) and inflammatory cytokines (explanatory variables). All significance testing will be two sided, with a p<0.05 considered significant. All analyses will be performed using Stata V.15.0.

As this is a follow-up study the sample size for the primary hypothesis is fixed. Assuming a 10% lost to follow-up and a rate of recurrent vascular events in the region of 6% per year,2 the study will have 83% power to detect a HR of 2, per unit rise in SUVmax, for the composite primary outcome of any major vascular event. This calculation is based on the observed baseline SD of SUVmax in the sample.

Findings to date

Patients recruited to BIOVASC and DUCASS underwent carotid 18F-FDG PET-CTA shortly after enrolment. Both studies showed that increased plaque 18F-FDG uptake was independently associated with early recurrent stroke at 90 days.33 34 The incorporation of 18F-FDG plaque uptake into a clinical prediction model also improves discrimination of early recurrent stroke, when compared with risk stratification by luminal stenosis alone.35 Improved methods to identify patients at the highest risk of stroke may refine selection for carotid revascularisation, allowing surgery to be targeted towards patients most likely to benefit. These findings show that plaque inflammation is a clinically important and independent predictor of early stroke recurrence in symptomatic carotid disease.

Strengths and limitations

An increasing body of evidence supports the hypothesis that inflammation plays an important role in stroke.36 However, prospectively designed multicentred studies relating blood and imaging biomarkers of inflammation to late outcome vascular events in stroke patients are lacking. While results from RCTs of anti-inflammatory agents in coronary patients have shown recent promise, better data is needed to inform the need for future trials of anti-inflammatory agents in a stroke population.

To our knowledge, BIOVASC-Late is the first multicentred observational study to investigate the prognostic utility of 18F-FDG PET-CTA for late outcome vascular events in stroke patients. It will also contribute important observations regarding the cross-sectional relationship between plaque FDG-uptake and (1) circulating inflammatory cytokines measured shortly after an acute stroke/TIA and (2) FDG-uptake in the contralateral asymptomatic carotid artery. Other strengths of the study include an in-person evaluation of suspected outcome events, blinded outcome assessments, rigorous quality assurance protocols to ensure standardisation of image acquisition, and a centralised/blinded image analysis. Finally, the anticipated median duration of follow-up in BIOVASC-Late will be 7 years, which surpasses most contemporary observational studies of stroke patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, as this is a late follow-up study, the sample size is fixed, which means that the analyses for some secondary outcomes may be underpowered. Second, there are limitations to PET-CTA as a plaque-imaging modality, including its limited spatial resolution and inability to identify potentially relevant plaque features (eg, intraplaque haemorrhage or surface ulceration), which have been associated with stroke recurrence. Furthermore, 18F-FDG PET use in clinical practice is limited by its availability in many centres, radiation exposure and high costs associated with its use. Nevertheless, it remains a valuable research tool for measuring FDG-uptake as a surrogate for vascular inflammation, which will help inform future clinical trials. While its routine use in clinical practice cannot yet be recommended, the added prognostic value over traditional risk factors may guide therapy for clinicians and reduce vascular risk in patients. This may ultimately reduce or nullify the overall costs of its use in the clinical setting. Third, as some patients will have died since recruitment, in-person evaluation will not be possible in these patients and adjudication of events will be limited to source documentation. This may lead to an underdetection or misclassification of outcomes. However, we expect that the utilisation of multiple overlapping sources to identify late outcomes will minimise the risk of this happening. Finally, age-specific and sex-specific variations in FDG-uptake, atherosclerotic plaque development and clinical endpoints are increasingly recognised.37 The majority of the patients in this study are older men (mean age 69.8 years, 68.4% male) and therefore this may limit the generalisability of our findings. However, any association between FDG-uptake and outcome will adjust for age and gender to mitigate against potential confounding.

While these limitations need to be borne in mind, BIOVASC-Late will help answer important questions regarding the long-term association between vascular inflammation (measured using 18F-FDG PET and circulating inflammatory cytokines) and recurrent major vascular events in stroke patients.

Collaboration

Access to the primary data will be made available on request to the corresponding author after final publication of the study findings. We also encourage collaboration with other investigators and will consider any reasonable request for data sharing initiatives to improve research in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All Stroke Clinical Trials Network Ireland (SCTNI) collaborators.

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it is published. The affiliation for David Williams has been updated.

Collaborators: The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of all investigators involved in the Stroke Clinical Trials Network Ireland (SCTNI) for their participation in patient recruitment and study oversight.

Contributors: JJM contributed to study design, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. NG contributed to the study design, data acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation. JM planned the study design, contributed to the acquisition of data, led the imaging data analysis and contributed to data management and manuscript preparation. SM contributed to study design, data acquisition, study conduct and manuscript preparation. MB contributed to the study design, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. TC contributed to the study design, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. SiC contributed to the study design, study conduct, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. ED contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. SF planned the study design, cion of data, contributed to imaging data analysis and manuscript

preparation. JH contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. SaC contributed to the study design, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. SeC contributed to data acquisition and manuscript preparation. GH contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, data acquisition, data management, outcome assessment and manuscript preparation. EK contributed to the study design, data acquisition and manuscript preparation. CM contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, data acquisition, and manuscript preparation. DW contributed to the study design, conduct of the study, data acquisition, and manuscript preparation. MO contributed to the study design, oversight of study PET procedures, data acquisition, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. MM planned the study design and contributed to data acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation. PK is the principal investigator of the BIOVASC and DUCASS Studies, planned the study design and contributed to data acquisition, data analysis, outcome adjudication and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by a Clinician Scientist Award grant received from the Health Research Board Ireland. The funding body did not contribute to the design of the study, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of this manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the Stroke Clinical Trials Network Ireland (SCTNI) for their participation in patient recruitment and study oversight.

PK receives funding from Health Research Board Ireland Clinician Scientist and Clinical Trials Network Awards, and the Irish Heart Foundation. DW receives funding from the Health Research Board of Ireland.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study has received ethical approval by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating hospital sites. Recruited patients provided written informed consent at enrolment. We plan to publish the findings of BIOVASC-Late in peer-reviewed journals and at international conferences appropriate to the field of research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Access to the primary data will be made available on request to the corresponding author after final publication of the study findings. We also encourage collaboration with other investigators and will consider any reasonable request for data sharing initiatives to improve research in the field.

References

- 1.Collaborators GBDS Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulanger M, Béjot Y, Rothwell PM, et al. . Long-Term risk of myocardial infarction compared to recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:JAHA.117.007267. 10.1161/JAHA.117.007267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marnane M, Prendeville S, McDonnell C, et al. . Plaque inflammation and unstable morphology are associated with early stroke recurrence in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke 2014;45:801–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redgrave JNE, Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, et al. . Histological assessment of 526 symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to the nature and timing of ischemic symptoms: the Oxford plaque study. Circulation 2006;113:2320–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.589044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002;420:868–74. 10.1038/nature01323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. . Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2497–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1912388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, et al. . Low-Dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:404–10. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. . Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Pradhan A, et al. . Low-Dose methotrexate for the prevention of atherosclerotic events. N Engl J Med 2019;380:752–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1809798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocker MS, Spence JD, Hammond R, et al. . [18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT imaging as a marker of carotid plaque inflammation: Comparison to immunohistology and relationship to acuity of events. Int J Cardiol 2018;271:378–86. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.05.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudd JHF, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, et al. . Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation 2002;105:2708–11. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000020548.60110.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudd JHF, Myers KS, Bansilal S, et al. . Relationships among regional arterial inflammation, calcification, risk factors, and biomarkers: a prospective fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography imaging study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:107–15. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.811752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figueroa AL, Abdelbaky A, Truong QA, et al. . Measurement of arterial activity on routine FDG PET/CT images improves prediction of risk of future cv events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:1250–9. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon SH, Cho YS, Noh TS, et al. . Carotid FDG uptake improves prediction of future cardiovascular events in asymptomatic individuals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:949–56. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. . C-Reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:132–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration, Danesh J, Lewington S, et al. . Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA 2005;294:1799–809. 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgakis MK, Malik R, Björkbacka H, et al. . Circulating Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 and Risk of Stroke: Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies Involving 17 180 Individuals. Circ Res 2019;125:773–82. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkind MSV, Luna JM, McClure LA, et al. . C-Reactive protein as a prognostic marker after lacunar stroke: levels of inflammatory markers in the treatment of stroke study. Stroke 2014;45:707–16. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Zhao X, Meng X, et al. . High-Sensitive C-reactive protein predicts recurrent stroke and poor functional outcome: subanalysis of the clopidogrel in high-risk patients with acute Nondisabling cerebrovascular events trial. Stroke 2016;47:2025–30. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.012901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Power DA, et al. . Fibrinogen concentration and risk of ischemic stroke and acute coronary events in 5113 patients with transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004;35:2300–5. 10.1161/01.STR.0000141701.36371.d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castillo J, Alvarez-Sabín J, Martínez-Vila E, et al. . Inflammation markers and prediction of post-stroke vascular disease recurrence: the MITICO study. J Neurol 2009;256:217–24. 10.1007/s00415-009-0058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehme AK, McClure LA, Zhang Y, et al. . Inflammatory markers and outcomes after lacunar stroke: levels of inflammatory markers in treatment of stroke study. Stroke 2016;47:659–67. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsh P, Lowe GDO, Chalmers J, et al. . Associations of proinflammatory cytokines with the risk of recurrent stroke. Stroke 2008;39:2226–30. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boellaard R, O'Doherty MJ, Weber WA, et al. . Fdg PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010;37:181–200. 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannotti N, O'Connell MJ, Foley SJ, et al. . Carotid atherosclerotic plaques standardised uptake values: software challenges and reproducibility. EJNMMI Res 2017;7:39. 10.1186/s13550-017-0285-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucerius J, Hyafil F, Verberne HJ, et al. . Position paper of the cardiovascular Committee of the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM) on PET imaging of atherosclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016;43:780–92. 10.1007/s00259-015-3259-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tawakol A, Fayad ZA, Mogg R, et al. . Intensification of statin therapy results in a rapid reduction in atherosclerotic inflammation: results of a multicenter fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography feasibility study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:909–17. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnsrud K, Skagen K, Seierstad T, et al. . 18F-FDG PET/CT for the quantification of inflammation in large carotid artery plaques. J Nucl Cardiol 2019;26:883–93. 10.1007/s12350-017-1121-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruno A, Shah N, Lin C, et al. . Improving modified Rankin scale assessment with a simplified questionnaire. Stroke 2010;41:1048–50. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, et al. . The Barthel ADL index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:61–3. 10.3109/09638288809164103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012;126:2020–35. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks KA, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, et al. . 2017 cardiovascular and stroke endpoint definitions for clinical trials. Circulation 2018;137:961–72. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marnane M, Merwick A, Sheehan OC, et al. . Carotid plaque inflammation on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts early stroke recurrence. Ann Neurol 2012;71:709–18. 10.1002/ana.23553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly PJ, Camps-Renom P, Giannotti N, et al. . Carotid Plaque Inflammation Imaged by 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography and Risk of Early Recurrent Stroke. Stroke 2019;50:1766–73. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly PJ, Camps-Renom P, Giannotti N, et al. . A risk score including carotid plaque inflammation and stenosis severity improves identification of recurrent stroke. Stroke 2020;51:838–45. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly PJ, Murphy S, Coveney S, et al. . Anti-Inflammatory approaches to ischaemic stroke prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018;89:211–8. 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Man JJ, Beckman JA, Jaffe IZ. Sex as a biological variable in atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2020;126:1297–319. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.