Abstract

Cell death plays a central role in normal physiology and in disease. Common to apoptotic and necrotic cell death is the eventual loss of plasma membrane integrity. We have produced a small organoarsenical compound, 4-(N-(S-glutathionylacetyl)amino)phenylarsonous acid, that rapidly accumulates in the cytosol of dying cells coincident with loss of plasma membrane integrity. The compound is retained in the cytosol predominantly by covalent reaction with the 90 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90), the most abundant molecular chaperone of the eukaryotic cytoplasm. The organoarsenical was tagged with either optical or radioisotope reporting groups to image cell death in cultured cells and in murine tumors ex vivo and in situ. Tumor cell death in mice was noninvasively imaged by SPECT/CT using an 111In-tagged compound. This versatile compound should enable the imaging of cell death in most experimental settings.

Cell death plays an integral role in physiology, including turnover of cells in the gastrointestinal tract,1 the menstrual cycle,2 and the immune system.3 Excessive cell death is characteristic of vascular disorders,4 neurodegenerative diseases,5 myelodysplastic syndromes,6 ischemia/reperfusion injury,7 and organ transplant rejection,8 among others. Cell death also plays a role in the treatment of disease. In cancer, for example, most chemotherapeutics, radiation treatments, and antihormonal agents act by inducing the death of cancer cells.9,10

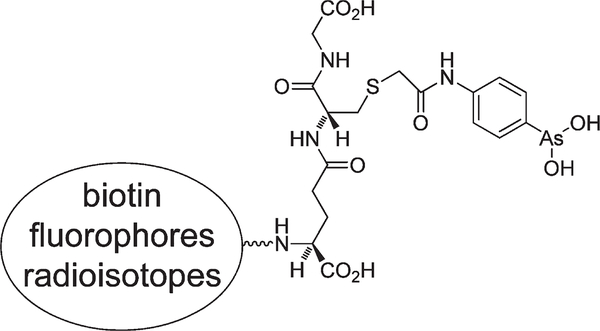

In view of the prevalence of cell death in normal physiology and disease, noninvasive imaging of this process is likely to have wide application in biological research and patient diagnosis and management. Here we describe a peptide trivalent arsenical, 4- (N-(S-glutathionylacetyl) amino)phenylarsonous acid (GSAO), that selectively labels dying and dead cells when conjugated to reporter groups through the γ-glutamyl amine (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of GSAO. The different reporter groups are linked through the amine of the γ-glutamyl residue.

Trivalent arsenicals cross-link two cysteine thiols in close proximity, forming stable cyclic dithioarsinites in which both sulfur atoms of the cysteine thiols are complexed to arsenic.11 This metalloid has very low reactivity for single protein thiols. Very few proteins react with trivalent arsenic in the extracellular milieu, as closely spaced protein cysteine thiols are usually oxidized to a cystine disulfide bond in this environment. The intracellular milieu, in contrast, contains a number of proteins that react with trivalent arsenic.12 Conjugates of GSAO with different reporter groups very selectively label dying cells.

Jurkat A3 cells13 were used to identify at what point in the death pathway cells are labeled with GSAO conjugates. GSAO linked to either Oregon Green (GSAO-OG) or Cy5.5 (GSAO-Cy5.5) was used to demonstrate the independence of the outcome on the reporting group. The control compound, 4-(N-(S-glutathionylacetyl)amino)benzoic acid (GSCA), contained an inert carboxylic acid group in place of the chemically reactive trivalent arsenic in GSAO. Three different cell-death inducers were employed to demonstrate the independence of the cell-death detection on the mechanism of cell death. A monoclonal antibody that binds the Fas/CD95 death receptor was used to trigger the extrinsic apoptotic pathway,14 while the microbial alkaloid staurosporine, a broad-spectrum protein kinase inhibitor, was used to activate the intrinsic or mitochondrialmediated pathway.15,16 The third cell-death mediator was the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin, which triggers G2/M growth arrest and apoptotic cell death and is used to treat various solid tumors, including soft-tissue sarcomas, aggressive lymphomas, and tumors of the breast, esophagus, and liver.17,18

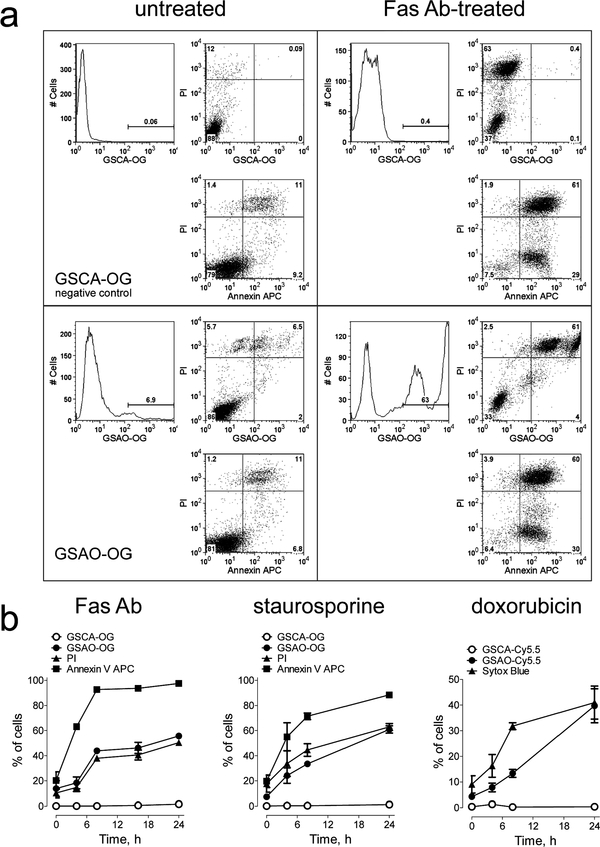

Jurkat A3 cells were treated with either Fas antibody staurosporine, or doxorubicin to induce apoptosis and then labeled with GSAO-OG or GSAO-Cy5.5; annexin V-APC, a marker of early-stage apoptosis; and propidium iodide (PI) or Sytox Blue, DNA binding agents that signal loss of plasma membrane integrity.19 Flow cytometry analysis showed that labeling with GSAO-OG or GSAO-Cy5.5 is coincident with that of PI or Sytox Blue (Figure 2a,b), indicating that the GSAO-fluorophore conjugates label cells at the point where the integrity of the plasma membrane is compromised. There was no labeling of cells with control GSCA conjugates.

Figure 2.

GSAO-fluorophore conjugates label cells during the mid-tolate stage of apoptosis, coincident with the loss of plasma membrane integrity, (a) Jurkat A3 cells were untreated or treated with Fas antibody (Ab) for 24 h to induce apoptosis, incubated with the GSCA-OG control (upper panels) or GSAO-OG (lower panels), annexin V-APC, and PI (all panels), and analyzed by flow cytometry. GSAO-OG-labeled cells (lower right panel) were also positive for annexin V-APC or PI (top right quadrant). The GSCA-OG control (upper panels) did not label any cells. The numbers on the histograms or scatter plots are the percentage of cells in the gate or quadrant, respectively, (b) Time courses of GSCA-OG and GSAO-OG labeling of Jurkat A3 cells treated with Fas antibody or staurosporine and GSCA-Cy5.5 and GSAO-Cy5.5 labeling of Jurkat A3 cells treated with doxorubicin. GSAO-OG or GSAO-Cy5.5 labeling was coincident with that of PI (Fas antibody and staurosporine) or Sytox Blue (doxorubicin), respectively, both markers of loss of plasma membrane integrity. The GSCA-OG and GSCA-Cy5.5 controls did not label any cells. Each data point and error bar represents the mean ± SD of three separate experiments.

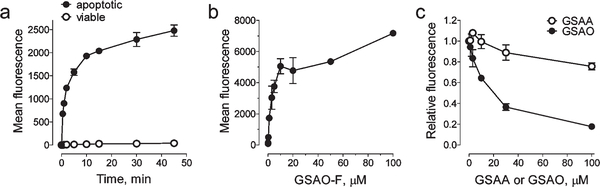

Human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells and a conjugate of GSAO with fluorescein (GSAO-F) were used to characterize the specificity and kinetic parameters of labeling. The time and concentration dependence of GSAO-F labeling of apoptotic versus viable HT1080 cells was measured. The mean fluorescence of the viable or apoptotic cell population was used to quantify the GSAO-F labeling.

The time required tor halt-maximal labeiing of annexin V-positive cells with 1 μM GSAO-F was ~1.6 min (Figure 3a), and halfmaximal labeling of GSAO-F over 15 min occurred at ~3.4μM (Figure 3b). There was ~1000-fold less labeling of viable cells (Figure 3a). Unconjugated GSAO competed for GSAO-F labeling of apoptotic cells, but the unconjugated 4-(N-(S-glutathionylacetyl) amino) phenylarsonic add (GSAA) control containing chemically unreactive As(V) in place of As(III) did not (Figure 3c). Halfmaximal inhibition of labeling of 1 μM GSAO-F over a 5 min interval occurred with ~16 μM unconjugated GSAO. GSAO labeling therefore, is rapid, saturable, and highly specific for dying cells.

Figure 3.

GSAO-fluorophore labeling of apoptotic cells is rapid and saturable, (a) Time dependence of the labeling of apoptotic vs viable HT1080 cells by 1μM GSAO-F. (b) Concentration dependence of the labeling of apoptotic HT1080 cells in a 15 min incubation, (c) Competition for GSAO-F labeling of apoptotic HT1080 cells by unconjugated GSAO and the GSAA control. Labeling is expressed as the fraction of the mean fluorescence with no unconjugated GSAO or GSAA. Each data point and error bar represents the mean and range of two separate experiments.

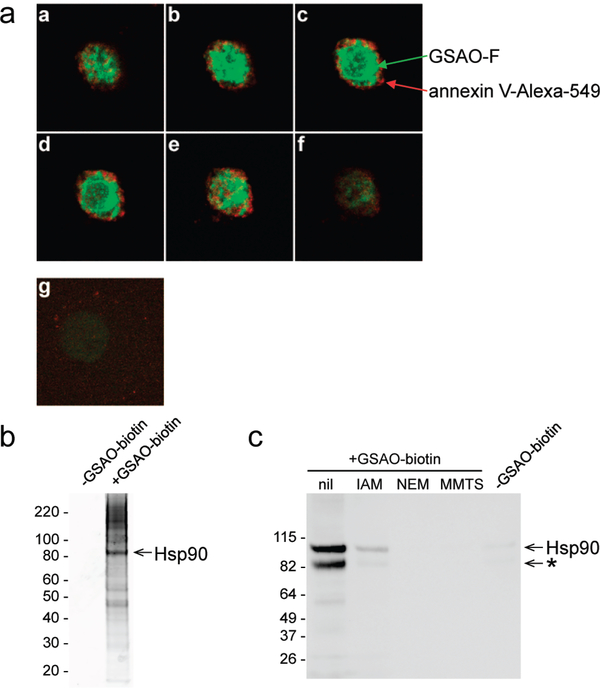

To determine the subceHular localization of GSAO-F in apoptotic cells, camptothedn-treatedHTlOSO cells were incubated with GSAO-F and annexin V-Alexa 594 and then imaged by confocal microscopy. GSAO-F was distributed in the cytoplasm of annexin V-positive cells (Figure 4a, panels a–f). There was negligible GSAO-F fluorescence in cells that did not stain with annexin V (Figure 4a, panel g).

Figure 4.

GSAO-fluorophore conjugates are retained in the cytosol predominantly by covalent reaction with Hsp90. (a) Fluorescence confocal image of a camptothecin-treated HT1080 cell incubated with GSAO-F (green) and annexin V-Alexa 594 (red). Panels a-fare serial transverse sections through a cell that labeled with annexin V. Panel g shows a cell that did not label with annexin V. (b) Staurosporine-treated Jurkat A3 cells were incubated without or with GSAO-biotin. The labeled proteins were collected on streptavidin beads, resolved on SDS-PAGE, and stained with Sypro Ruby. The major labeled band was identified as Hsp90 by mass spectrometry. The positions of Mr markers are indicated at the left, (c) GSAO-biotin reacts with cysteine thiols in Hsp90. Purified Hsp90 was incubated without or with the small thiol alkylators iodoacetamide (IAM), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and methyl methanethiolsulfonate (MMTS) and then labeled with GSAO-biotin. Complex formation was measured by blotting with streptavidinperoxidase. To control for nonspecific blotting with streptavidinperoxidase, GSAO-biotin was omitted in the experiment shown in the last lane. The positions of Mr markers are indicated at the left. * indicates an Hsp90 degradation product.

To identify the proteins that react with GSAO conjugates in the cytosol, staurosporine-treated Jurkat A3 cells were incubated without or with the biotinylated compound (GSAO-biotin), and the labeled proteins were collected on streptavidin beads, resolved on SDS-PAGE, and stained with Sypro Ruby (Figure 4b). The major labeled band had an Mr of ~90 kDa and was identified as Hsp90 by mass spectrometry. In addition, an LC-MS/MS analysis of the insolution tryptic digest of all GSAO-biotin-labeled proteins showed on the basis of mass-spectral counts20 that Hsp90 is the most abundant protein. It is roughly twice as abundant as the next most abundant proteins, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 and filamin A (110 spectral counts vs 58 and 57, respectively). The reaction of GSAO-biotin with Hsp90 was confirmed in assays using the purified protein (Figure 4c). The reaction was dependent on the presence of cysteine thiols in Hsp90, as prior alkylation of the thiols blocked the interaction with GSAO-biotin.

Hsp90 plays a central role in a number of fundamental cellular pathways by mediating the folding, stabilization, activation, and assembly of a variety of “client” proteins.21,22 Notably, tumor cell malignancy is dependent on higher than noimal activity of Hsp90, which assists the folding/stabilization of oncoproteins and other unstable mutant or overexpressed proteins.23 Hsp90 is the most abundant chaperone of the eukaryotic cytoplasm and contains a highly conserved Cys-Cys motif in the C-tenninal domain.24 This pair of cysteines (Cys719 and Cys720 in the human protein) are involved in redox reactions in the cytoplasm and are cross-linked by the trivalent arsenical arsenite.24 The effectiveness of an imaging agent is determined in part by how much of the agent accumulates in a given volume. A high concentration of imaging agent at the target results in better limits of detection and resolution. The abundance of Hsp90 in the cytosol allows for high levels of GSAO conjugates in apoptotic cells and therefore superior detection and resolution of cell death.

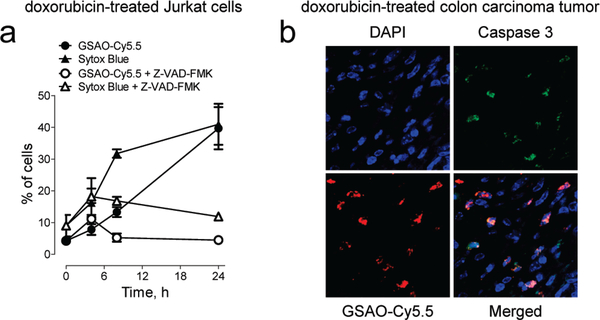

Solid tumors generally contain laige numbers of dying and dead cells. This is thought to be due to the high rate of cell death in tumors coupled with restricted rate of access of macrophages to the dying cells. GSAO was conjugated to the near-IR fluorescent dye Cy5.5 to image doxorubicin-mediated tumor cell death in murine colon tumors. GSAO-Cy5.5 detected the doxorubicin-mediated death of cultured cells (Figure 2b), which is caspase-dependent (Figure 5a). The caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK25 inhibited labeling of the cells by both GSAO-Cy5.5 and Sytox Blue (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

GSAO-fluorophore conjugate labels apoptotic tumor cells in mice, (a) Time course of GSAO-Cy5.S labeling of Jurkat A3 cells treated with doxorubicin in the absence or presence of the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Blocking doxorubicin-mediated apoptosis with the caspase inhibitor inhibited GSAO-Cy5.5 labeling. Each data point and error bar represents the mean ± SD of three separate experiments, (b) Balb/c mice bearing CT26 colorectal carcinoma tumors in the flank were treated with doxorubicin and the following day were administered 1 mg/kg GSCA-Cy5.5 or GSAO-Cy5.5. After 1 h, the tumors were excised, sectioned, stained for activated caspase 3, and counterstained with a nucleic acid stain (DAPl). Fluorescence confocal microscopy showed that cells that were positive for activated caspase 3 (green) were also positive for GSAO-Cy5.5 (red). There was no detectable GSCACyS.5 in any tumor section analyzed.

Mice bearing subcutaneous murine CT26 colorectal carcinoma tumors were treated with doxorubicin by tail-vein injection to induce tumor cell death. GSAO-Cy5.5 was injected in the tail vein the day after treatment, and the tumors were excised 1 h later. Cell death was detected by staining of tumor sections with an antibody to activated caspase 3. Cells that were positive for activated caspase 3 were also positive for GSAO-Cy5.5 (Figure 5b). GSAO-Cy5.5 did not label caspase 3-negative cells. The GSCA-Cy5.5 control was not detected in any of the tumor sections analyzed.

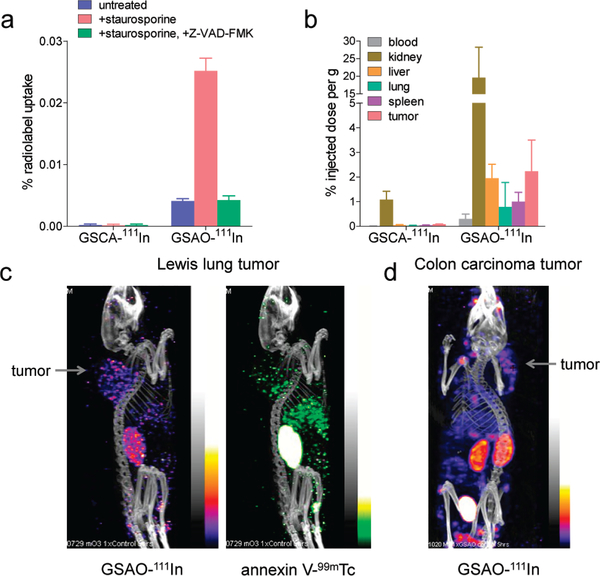

GSAO was conjugated to a DTPA-111 In chelate (DTPA = diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) for noninvasive imaging of tumor cell death in murine Lewis lung tumors. Staurosporine treated Jurkat cells were incubated with GSAO-111 In to test the labeling of apoptotic cells with this conjugate. The labeling of treated cells with the 1llIn conjugate was 6.1-fold greater than that of untreated cells, and the labeling was comparable to that of untreated cells when caspases were inhibited (Figure 6a). There was no labeling of the cells with the GSCA-111In control.

Figure 6.

Noninvasive imaging of tumor cell death in mice using a GSAO-radioisotope conjugate, (a) Jurkat A3 cells were untreated or treated with staurosporine without or with the caspase inhibitor Z-VADFMK. The GSC-111In control or GSAO-111In was incubated with the cells, and the bound radioactivity was measured. Each data point and error bar represents the mean ± SD of three separate experiments, (b) Biodistribution of the GSCA-111In control or GSAO-111 In in C57BL/ 6 mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma tumors. The results are presented as % injected dose per gram of tissue weight 5 h after injection. Data points and error bars represent means ± SD of 4 to 68 separate measurements, (c) A C57BL/6 mouse bearing a Lewis lung carcinoma tumor in the shoulder area was administered GSAO-111In and annexin V-99mTc in the tail vein, and dual SPECT/CT images were collected S h later in separate energy windows. The position of the tumor is indicated, (d) A Balb/c mouse bearing a CT26 colorectal carcinoma tumor in die shoulder area was administered GSAO-111In in die tail vein, and a SPECT/CT image was collected 5 h later. The position of die tumor is indicated.

To determine whether GSAO was suitable as a noninvasive cell-death imaging agent, we examined its labeling of organs in mice bearing solid tumors. Mice bearing subcutaneous murine Lewis lung tumors were injected with the GSCA-111In control or GSAO-l11In in the tail vein, and after 5 h the blood, kidneys, livers, lungs, spleens, and tumors were harvested to examine the biodistribution of the compounds. GSAO-111In was mostly present in die kidneys, where the compound is excreted. Fluorophore conjugates of GSAO were also observed in the urine within 30 min of intravenous or subcutaneous administration. A few percent of the compound was found in the liver, lungs, spleen, and tumor (Figure 6b; also see the Supporting Information). Very low levels of die GSCA-111In control were found in the organs. There were no signs or symptoms of toxicity of the compounds in mice.

Mice beaiing subcutaneous murine Lewis lung tumors were injected with GSAO-111In and annexin V-99mTc in the tail vein, and dual SPECT/CT images were collected 5 h later. GSAO-111In was observed in the kidneys and tumor, while annexin V-99mTc was found in the kidneys, tumor, and liver (Figure 6c). The liver localization of annexin V is in accordance with the site of metabolism of this protein.26,27 The GSAO-111In image of a subcutaneous murine CT26 colorectal carcinoma was comparable to that of the Lewis lung tumor image (Figure 6d). The GSCA11lIn control was not detectable when used in place of GSAO-111In in these tumor models.

There was a punctuate distribution ot the radiolabeled compounds in the tumor, which is consistent with labeling of patches of dying or dead cells. This pattern of tumor cell death is what is typically observed histologically.

Annexin V is the best-studied agent tor in vitro and in vivo imaging of apoptosis. It is a 35 kDa protein that detects disruption of plasma membrane asymmetry in dying cells by binding to exteriorized phosphatidylserine.28 Radiolabeled annexin V has been evaluated in a number of phase-II oncology trials, and its development is ongoing,29 Other phospholipid binding compounds have also been evaluated,30,31 but their utility may be limited by sensitivity and/or biodistribution issues. A small, synthetic caspase ligand has shown promise in animal studies,32 although it may not be specific for apoptotic cells.33,34 In addition, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes La protein in the cytosol of dying/dead cells can be used to image tumor cell death in mice when radiolabeled.35

GSAO conjugates have the advantages of chemical stability, exquisite selectivity for dying cells, and versatility with respect to the reporting group. The nature and abundance of its cytosolic target, Hsp90, also bodes well for this compound’s suitability as a cell-death imaging agent

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Mark Raftery and Gavin Mackenzie for assistance with mass spectrometry and microscopy respectively. This study was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the New South Wales Cancer Council, and a fellowship (K.C.) from the American Society of Therapeutic Radiation Oncology.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Rama chan dran A; Madesh M; Balasubramanian KA J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dahmoun M; Boman K; Cajander S; Westin P; Backstrom TJ Clin. Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84, 1737–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ju ST; Matsui K; Ozdemirli M Int Rev. Immunol. 1999, 18, 485–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Stefanec T Chest 2000, 117, 841–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mattson MP Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 1, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Parker JE j Mufti GJ Int. J. Hematol. 2001, 73, 416–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gottlieb RA; Engler RL Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 874, 412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Krams SM; Martinez OM Semin. Liver Dis. 1998,18,153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Thompson CB Science 1995, 267, 1456–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rupnow BA; Knox SJ Apoptosis 1999, 4, 115–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Adams E; Jeter D j Cordes AW; Kolis JW Inorg. Chem 1990, 29, 1500–1503. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Dilda PJ; Hogg PJ Cancer Treat. Rev. 2007, 33, 542–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Juo P; Kuo CJ; Yuan J; Blenis J Curr. Biol. 1998, 8, 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Danial NN; Korsmeyer SJ Cell 2004, 116, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Scarlett JL; Sheard PW; Hughes G; Ledgerwood EC; Ku HH ; Murphy MP FEBS Lett. 2000, 475, 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tafani M; Minchenko DA; Serroni A; Farber JL Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2459–2466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gewirtz D A Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 727–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Minotti G; Menna P; Salvatorelli E; Cairo G; Gianni L Pharmacol. Rev. 2004, 56, 185–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Darzynkiewicz Z j Juan G; Li X; Gorczyca W; Murakami T; Traganos F Cytometry 1997, 27, 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Liu H; Sadygov RG; Yates JR, III. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 4193–4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hahn JS BMB Rep. 2009, 42, 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Csermely P; Schnaider T; Soti C; Prohaszka Z; Nardai G Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 79, 129–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Pearl LH; Prodromou C; Workman P Biochem. J. 2008, 410, 439–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Nardai G; Sass B; Eber J; Orosz G; Csermely P Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 384, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhu H; Fearnhead HO; Cohen GM FEBS Lett. 1995,374, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tait JF; Smith C; Blankenberg FG J. Nucl.Med 2005,46,807–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kartachova M; Haas RL; Olmos RA; Hoebers FJ; van Zandwijk N j Verheij M Radiother. Oncol 2004, 72, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Koopman G; Reutelingsperger CP; Kuijten GA; Keehnen RM j Pals ST; van Oers MH Blood 1994,84,1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Blankenberg FG Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1525–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Thapa N; Kim S; So IS; Lee BH; Kwon IC; Choi K; Kim IS J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 1649–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Cohen A; Ziv I; Aloya T; Levin G; Kidron D; Grimberg H; Reshef A; Shirvan A Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2007, 6, 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Faust A; Wagner S; Law MP; Hermann S j Schnockel U; Keul P; Schober O; Schafers M; Levkau B; Kopka KQ, J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 51, 67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Rosado JA; Lopez JJ; Gomez-Arteta E; Redondo PC; Salido GM; Pariente JA J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 209, 142–1S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Spires-Jones TL; de Calignon A; Matsui T j Zehr C; Pitstick R; Wu HY j Osetek JD; Jones PB; Bacskai BJ; Feany MB; Carlson GA; Ashe KH; Lewis J; Hyman BT J. Neurosci 2008,28, 862–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Al-Ejeh F; Darby JM; Tsopelas C; Smyth D; Manavis J; Brown MP PLoS One 2009, 4, No. e4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.