Abstract

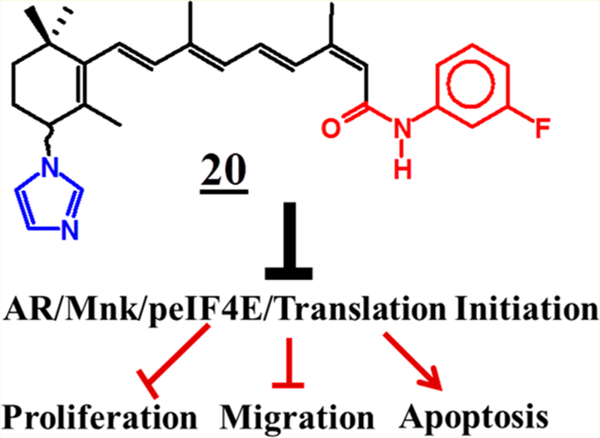

The synthesis and in vitro and in vivo antibreast and antiprostate cancers activities of novel C-4 heteroaryl 13-cis-retinamides that modulate Mnk-eIF4E and AR signaling are discussed. Modifications of the C-4 heteroaryl substituents reveal that the 1H-imidazole is essential for high anticancer activity. The most potent compounds against a variety of human breast and prostate cancer (BC/PC) cell lines were compounds 16 (VNHM-1–66), 20 (VNHM-1–81), and 22 (VNHM-1–73). In these cell lines, the compounds induce Mnk1/2 degradation to substantially suppress eIF4E phosphorylation. In PC cells, the compounds induce degradation of both full-length androgen receptor (fAR) and splice variant AR (AR-V7) to inhibit AR transcriptional activity. More importantly, VNHM-1–81 has strong in vivo antibreast and antiprostate cancer activities, while VNHM-1–73 exhibited strong in vivo antibreast cancer activity, with no apparent host toxicity. Clearly, these lead compounds are strong candidates for development for the treatments of human breast and prostate cancers.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Disruption and/or perturbation of cap-dependent translation is essential for the development of cancers and many fibrotic diseases, the most notable being Alzheimer’s disease.1 Hyper-activation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), the mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein of cap-dependent translation, promotes exquisite transcript-specific translation of key mRNAs that are indispensable in cancer initiation, progression, and metastases.2 The oncogenic potential of eIF4E is dependent on serine 209 phosphorylation by MAPK-interacting kinases 1 and 2 (Mnk1/2). Currently, there are several strategies, directed at disruption of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex to inhibit hyperactivity of oncogenic protein translation as a means to effectively treat a variety of cancers.3

When targeting a critical process such as translation, a major critical question is whether the drug will have significant effects on normal cellular processes, leading to limiting toxicities and too narrow a therapeutic window. This question has been addressed by several experimental and a few clinical studies. Recently, Graff and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that down-regulation of eIF4E by antisense oligonucleotide therapy caused reduction of in vivo tumor growth in MDA-MB-231 breast and PC-3 prostate cancer models without toxicity despite an ∼80% eIF4E knockdown in essential organs.4 These data provided in vivo evidence that cancers may be more susceptible to eIF4E inhibition than normal tissue and provided the basis for advancement of eIF4E-specific antisense molecule LY2275796 into phase 1 clinical studies.5 In other more recent studies, cercosporamide, a potent Mnk1/2 kinase inhibitor, was reported to exhibit antitumor efficacies against HCT116 colon carcinoma xenograft tumors6 and MV4–11 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) tumors in animal models,7 without any toxicity.

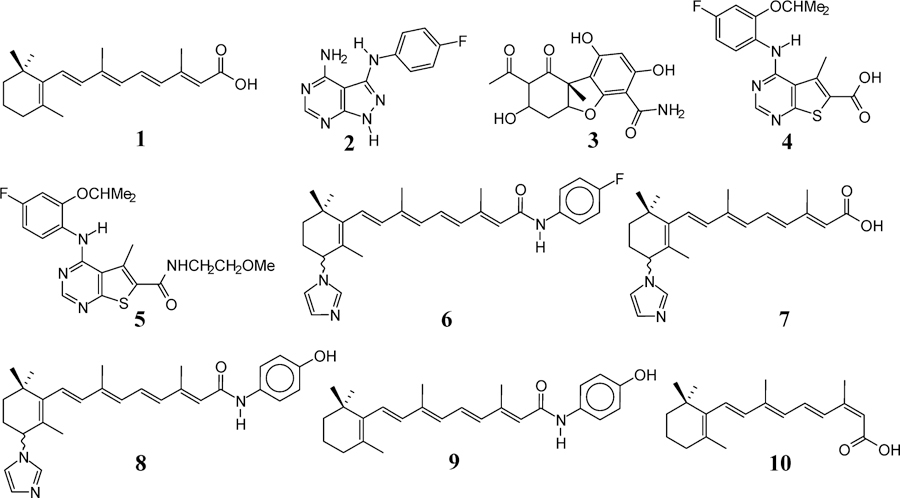

We previously reported that our proprietary novel C-4 azolyl retinamides (NRs) based on all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) (1) (Figure 1) scaffold induced apoptosis, potently inhibited the growth, migration, and invasion of a variety of human breast and prostate cancer cell lines.8 With respect to the breast cancer cell lines, we demonstrated that the antibreast cancer activity of our NRs was due mainly to degradation of Mnk1/2 with subsequent suppression of phosphorylated eIF4E (peIF4E).8a However, in the prostate cancer (PC) cell lines, we demonstrated that the antitumor activity of the NRs was due to simultaneous inhibition of the Mnk/eIF4E and androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathways.8b It is important to state here that unlike other reported small molecules that inhibit Mnk1/2 kinase activities,3e,6,9 our NRs induced Mnk1/2 degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway with resultant depletion of peIF4E.8 The structures of promising Mnk1 and/or Mnk2 kinase inhibitors, including CGP57380 (2),10 cercosporamide (3),6 MNKI-19 (4),11 and MNKI85 (5),11 are presented in Figure 1. In addition, the structures of our lead Mnk degrading agent (MNKDA), VNLG-152 (6)8a and related compounds,12 VN/14–1 (7), VN/66–1 (8), and N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (4-HPR or fenretinide) (9) are also depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–10.

In the present study, we have synthesized novel compounds based on 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-CRA) (10) (Figure 1) scaffold, and their anticancer activities were evaluated in both in vitro and in vivo models of human breast and prostate cancers. These novel compounds target Mnk1/2 degradation in both breast cancer and PC cells and also induce AR degradation in PC cells, which in turn led to induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, inhibition of cell growth, colonization, migration, and invasion. Importantly, compounds 20 and 22 significantly inhibited tumor growth of aggressive MDA-MB-213 breast cancer xenografts, while 20 was shown to substantially suppress castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) CWR22Rv1 xenografts in vivo.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design Strategy.

Rationale structural modifications of small molecules allow for their interactions with molecular target(s) in ways that could lead to improved druglike compounds and possibly enhanced in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles.13 Because of our desire to discover more efficacious anticancer agents, we were eager to exploit compound 10’s scaffold as a strategy to novel potent/efficacious MNKDAs with improved druglike properties. The rationale of using this scaffold is based on experimental and clinical reports that, unlike ATRA (1), 13-CRA (10) has long elimination half-life in humans14 and most animal species.15 In addition, we also explored rational modification of the terminal amide moiety, C-4 heterocycles, and the cyclohexene ring (Figure 2). It is relevant to state here that our previous studies with the ATRA scaffold MNKDAs identified the C-4 azolyl retinamides to be superior to the corresponding carboxylic acid and esters.8

Figure 2.

Overall design strategy for novel C-4 heteroaryl 13-cis-retinamides.

C-4 Azoyl/Terminal Amide Modifications.

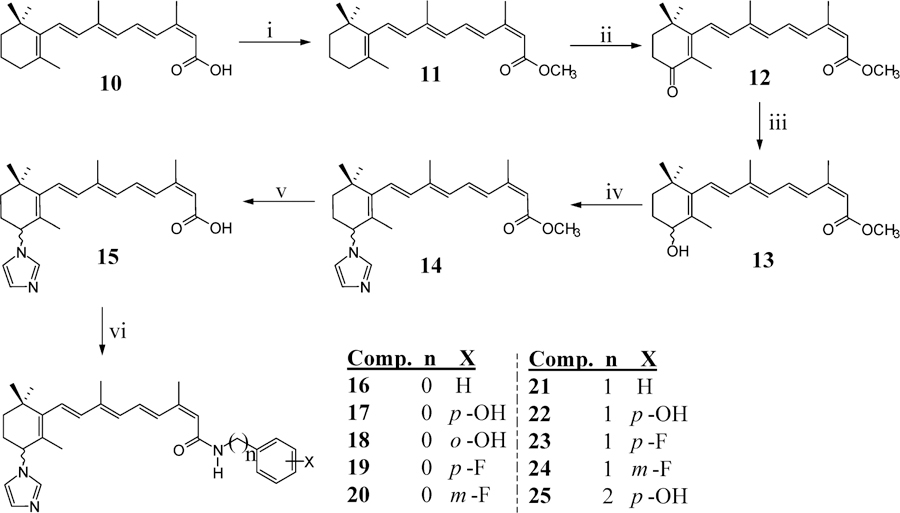

On the basis of the continued successes of the C-imidazole retinamides with the ATRA scaffolds as promising anticancer agents,8 we designed and synthesized compounds 16–25 as outlined in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of C-4 Azoyl/Terminal Amide Compounds 17–22a

aReagents and conditions: (i) (CH3)3SiCHN2, MeOH/benzene; (ii) MnO2, CH2Cl2; (iii) NaBH4, MeOH; (iv) CDI, CH3CN; (v) 2 M KOH, MeOH, reflux; (vi) EDC, HOBT, DIEA, appropriate anilines, DMF.

Cyclohexene Rigidification/C-4 Aryl and Heteroaryl Modifications.

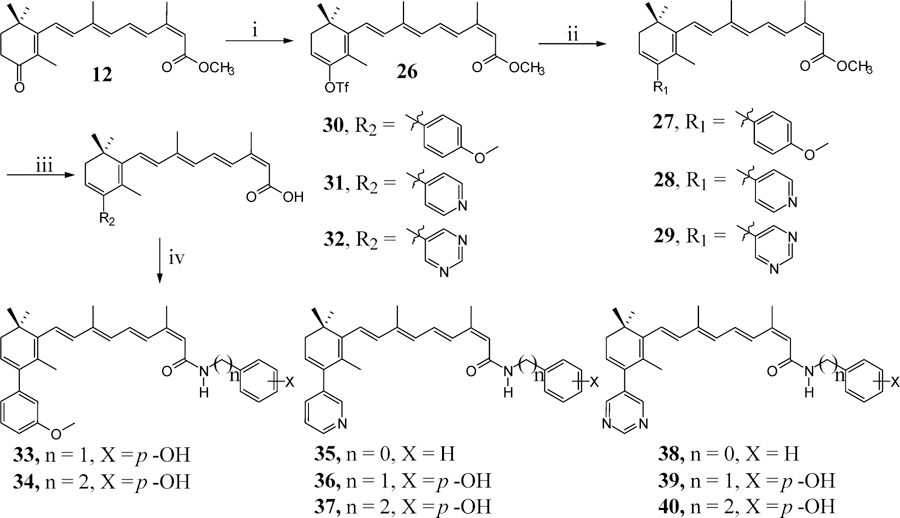

On the basis of previous studies that showed that structural rigidification that introduces conformational constraints around rotatable bonds contributed to higher specificity and potency, greater metabolic stability, and improved bioavailability,16 we designed and synthesized several cyclohexadiene C-4 aryl substituted retinamides, compounds 33–40 (Scheme 2). A potential advantage of this strategy is that the achiral nature of these compounds would not require the tedious characterization of the racemates and pure enantiomers as would be required in advanced preclinical development for the chiral compounds of Scheme 1.17

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Cyclohexen Rigidification/C-4 Aryl and Heteroaryl Retinamidesa

aReagents and conditions: (i) 5-chloro-2-pyridyltriflimide, NaN(SiMe3)2, THF; (ii) 3-methoxybenzylboronic acid, Pd(PPh3)4, CeCO3, dioxane, reflux; (iii) 2 M KOH, MeOH, reflux; (iv) EDC, HOBT, DIEA, appropriate benzylamine, DMF.

Chemistry.

Herein, we report, for the first time, the synthesis of 18 novel compounds based on the structural scaffold of 13-CRA (10), as outlined in Schemes 1 and 2.

The synthesis of (2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoic acid (15) was carried out in five steps from the commercially available 13-CRA (10), and the procedure was adopted from our reported procedures of ATRA based retinamides.12b Protection of the carboxylic acid as the methyl ester (11) was done using trimethylsilyldiazomethane in Reduction of 12 using NaBH4 gave the (±)-4-hydroxymethyltetraenoate (13) which was further treated with carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) at ambient temperature to yield (±)-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)methyltetraenoate (14). Alkaline hydrolysis of 14 in refluxing methanol gave the desired free acid 15 in 63% yield. Coupling of the respective amines with 15 was successfully achieved using ethyl(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) to give compounds 16–25 (Scheme 1), respectively, in average yields of ∼50%.

The synthesis of achiral C-4 aryl retinamides 33–40 (Scheme 2) commenced from the 4-oxo intermediate (12). Generation of enolate using sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide in THF solution and trapping of the enolate with N-(5-chloro-2-pyridyl)bistrifluoromethanesulfonimide furnished the vinyl triflate 26 in 75% yield according to the reported procedure.18 However, it should be noted that this reaction was carried out at −78 °C throughout the reaction time because at higher temperatures, decomposition occurred and ≤20% of the products were obtained. Regiospecific palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction with boronic acids19 provided compounds 27–29 in 88%, 69%, and 60% yields, respectively. Ester hydrolysis using 2 M KOH gave the corresponding free acids 30–32 in 62%, 48%, and 70% yields, respectively. Coupling of these respective acids with appropriate amines was successfully achieved using EDC, HOBt, and DIEA to give compounds 33–40, respectively, in average yields of ∼50% (Scheme 2).

Biological Studies.

Effects of 13-cis-Retinamides on the Growth of Breast and Prostate Cancers Cells in Vitro.

We determined the effects of the 13-cis-NRs on human cancer cell proliferation using a variety of breast and prostate cancer cells lines using our previously described MTT assay procedures.8,12b,20 The results (GI50 values) are summarized in Table 1. Growth inhibitory concentrations (GI50 values) are the concentrations of compounds that cause 50% growth inhibition obtained from dose–response curves. The clinically relevant retinoids ATRA and 4-HPR and the Mnk inhibitor cercosporamide were used as comparators in the assays.

Table 1.

Inhibitory Concentrations (GI50, μM) of NRs and Reference Compounds on the Growth of Human Breast Cancer Cells in Vitro

| compd | GI50 (μM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | MDA-MB-468 | SKBR-3 | |

| 16 | 1.90 ± 0.00 | 1.74 ± 0.22 | 2.54 ± 0.12 | 1.73 ± 0.09 |

| 17 | 1.99 ± 0.26 | 13.05 ± 1.06 | 6.83 ± 0.33 | 3.89 ± 0.12 |

| 18 | 1.09 ± 0.00 | 4.67 ± 0.14 | 3.03 ± 0,39 | 3.89 ± 0.06 |

| 19 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 4.95 ± 0.24 | 4.57 ± 0.00 | 25.11 ± 1.03 |

| 20 | 5.49 ± 0.11 | 8.51 ± 0.16 | 6.76 ± 0.23 | 16.98 ± 0.79 |

| 21 | 9.77 ± 0.64 | 5.88 ± 0.27 | 7.24 ± 0.14 | 10.71 ± 0.98 |

| 22 | 0.16 ± 0.00 | 2.23 ± 0.07 | 2.70 ± 0.35 | 2.45 ± 0.09 |

| 23 | 1.93 ± 0.16 | 1.41 ± 0.06 | 2.45 ± 0.06 | 5.50 ± 0.00 |

| 24 | 1.81 ± 0.15 | 1.65 ± 0.04 | 3.09 ± 0.18 | 4.24 ± 0.21 |

| 25 | 1.90 ± 0.08 | 2.88 ± 0.08 | 13.48 ± 0.97 | 1.41 ± 0.03 |

| 33 | c | c | c | c |

| 34 | c | c | c | c |

| 35 | 8.32 ± 1.75 | 25.11 ± 0.76 | 39.81 ± 1.33 | 47.40 ± 3.85 |

| 36 | c | c | c | c |

| 37 | 8.75 ± 1.14 | 26.91 ± 0.98 | 50.11 ± 2.40 | 42.24 ± 3.44 |

| 38 | 7.01 ± 0.57 | 26.91 ± 1.23 | 22.90 ± 1.03 | 30.98 ± 3.02 |

| 39 | 4.96 ± 0.24 | 11.48 ± 1.07 | 19.05 ± 1.22 | 11.48 ± 0.00 |

| 40 | 2.96 ± 0.29 | 14.45 ± 0.92 | 23.44 ± 0.96 | 23.99 ± 0.00 |

| ATRAb | ndd | 14.12 ± 0.86 | 14.12 ± 0.55 | 22.90 ± 0.15 |

| 4-HPR | 4.65 | 11.05 ± 1.12 | 6.02 ± 0.17 | 3.98 ± 0.16 |

| cercosporamideb | nd | 43.65 ± 0.17 | 47.86 ± 0.23 | 26.02 ± 0.87 |

The GI50 values were determined from dose–response curves (by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism) compiled from at least three independent experiments using indicated breast cancer cells, SEM < 10%, and represent the compound concentration required to inhibit cell growth by 50%.

Previously reported in S. Ramalingam et al.8a

≥40% inhibition of breast cancer cell growth at 10 μM.

nd = not determined.

Antiproliferative Activities in Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

As stated earlier, the structural modification focused on modifications of the terminal amide, cyclohexe ring, and C-4 substituents. As presented in Table 1, several important generalizations emerge from the antiproliferative data. First, most of our compounds, including compounds 16–25, possess higher antiproliferative activities toward all four breast cancer cell lines than the positive controls, ATRA, 4-HPR, and the Mnk inhibitors, as evidenced by the lower GI50 values (Table 1). Second, for each compound, the antiproliferative activities toward the breast cancer cell lines varied significantly. In general, the MCF-7 cell line was the most sensitive, while the SKBR-3 was the least sensitive to these compounds. Third, for a given breast cancer cell line, the antiproliferative activity depends largely on the structure of the NR, which in turn depends largely on the nature of the C-4 heterocycle and cyclohexene/cyclohexadiene ring. [1] Compounds with the imidazole tethered to C-4 of the cyclohexene ring (16–25) exhibit more potent antiproliferative activities than compounds with phenyl (33 and 34), pyridine (35–37), or pyrimidine (38–40) tethered to C-4 of the cyclohexadiene ring. [2] Compared to compound 16, which possesses an unsubstituted amide phenyl ring, compounds with substituted hydroxyl (17 and 18) or fluoro (19 and 20) groups displayed mixed antiproliferative activities but in general were either equipotent or less active than compound 16. The only exception was p-fluoro compound (19) with GI50 = 0.4 μM against MCF-7 cells and was ∼4.8-fold more potent than 16 (GI50 = 1.90 μM). [3] Insertion of a methylene moiety between the amide and phenyl group clearly led to decreased antiproliferative activities (compare GI50 values of 16 (1.74–2.54 μM) to GI50 values of 21 (5.88–10.71 μM)). [4] However, ortho/para hydroxyl or fluoro substitutions to benzyl group of 21 to give compounds 22–24 led to enhanced antiproliferative activities across the four breast cancer cell lines. Among these three compounds, 22 was the most potent with GI50 values of 0.16, 2.23, 2.70, and 2.45 μM versus MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and SKBR-3 cell lines, respectively. Related compound 25 with an ethylene moiety between the amide and p-hydroxyl group led to varied antiproliferative activities. It is notable that 25 among these compounds exhibited the best activity (GI50 = 1.41 μM) against the SKBR-3 cell line.

Antiproliferative Activities in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines.

The GI50 values of compounds 16–22 against three human prostate cancer cell lines, including, LNCaP, CWR22Rv1, and PC-3, were determined and compared to the GI50 values of clinically relevant drugs, ATRA, 4-HPR, casodex, and MDV3100 (enzalutamide) (Table 2). In general, the compounds were more potent than ATRA but were equipotent to 4-HPR, casodex, and MDV3100. The PC-3 cell line was the least sensitive to all the compounds tested. Compounds 20 and 22 exhibited the most potent antiproliferative activities across the three cell lines.

Table 2.

Inhibitory Concentrations (GI50, μM) of NRs and Reference Compounds on the Growth of Human Prostate Cancer Cells in Vitro

| compd | GI50 (μM)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| LNCaP | CWR22Rv1 | PC-3 | |

| 16 | 2.69 ± 0.09 | 1.28 ± 0.03 | 8.91 ± 0.51 |

| 17 | 3.54 ± 0.18 | 3.89 ± 0.08 | 11.74 ± 0.76 |

| 18 | 3.23 ± 0.19 | 2.23 ± 0.11 | 15.48 ± 0.87 |

| 19 | 3.89 ± 0.23 | 8.12 ± 0.52 | 30.19 ± 0.94 |

| 20 | 2.69 ± 0.14 | 2.04 ± 0.01 | 5.62 ± 0.03 |

| 21 | c | c | c |

| 22 | 1.69 ± 0.07 | 1.86 ± 0.06 | 3.54 ± 0.02 |

| ATRAb | 47.86 ± 0.21 | 25.11 ± 0.16 | 36.3 ± 0.27 |

| 4-HPRb | 2.69 ± 0.14 | 3.23 ± 0.08 | 3.54 ± 0.09 |

| Casodexb | 2.61 ± 0.09 | 3.81 ± 0.18 | 9.15 ± 0.14 |

| MDV3100b | 2.88 ± 0.13 | 3.34 ± 0.25 | 9.15 ± 0.26 |

The GI50 values were determined from dose–response curves (by nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism) compiled from at least three independent experiments using LNCaP cells, SEM < 10%, and represent the compound concentration required to inhibit cell growth by 50%.

Previously reported by V. Ramamurthy et al.8b

Requires >100 μM to induce 50% inhibition of cell growth in PC cells.

In Vitro Characterization of Compounds 16, 20, and 22 in Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

We previously reported that the antiproliferative effects of the first generation MNKDAs in breast cancer cells was due to degradation of Mnk1/2 with subsequent depletion of peIF4E and induction of apoptosis.8a To determine if these compounds modulate Mnk1/2 and related oncogenic proteins, we performed Western blot of lysates from MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cells treated with compounds 16, 20, and 22 or with vehicle (DMSO, negative control) or compound 6 (positive control). Figure 3 shows that the three compounds significantly and dose-dependently reduced the expressions of Mnk1, Mnk2, and peIF4E, with no noticeable effects on the expression of total eIF4E. The compounds also caused dose-dependent formation of c-PARP which indicates induction of cell death (apoptosis).

Figure 3.

Effect of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on Mnk1, Mnk2, peIF4E, eIF4E, and cPARP proteins in MCF-7 cells. Equal protein concentrations from MCF-7 (A), MDA-MB-231 (B), and MDA-MB-468 (C) cells treated for 24 h with 16, 20, and 22 at the various concentrations as indicated and 6 (20 μmol/L) were separated by SDS–PAGE and Western blots probed with antibodies to Mnk1, Mnk2, peIF4E, eIF4E, and cPARP. Vehicle treated cells were included as control, and all blots were reprobed for GAPDH for loading control.

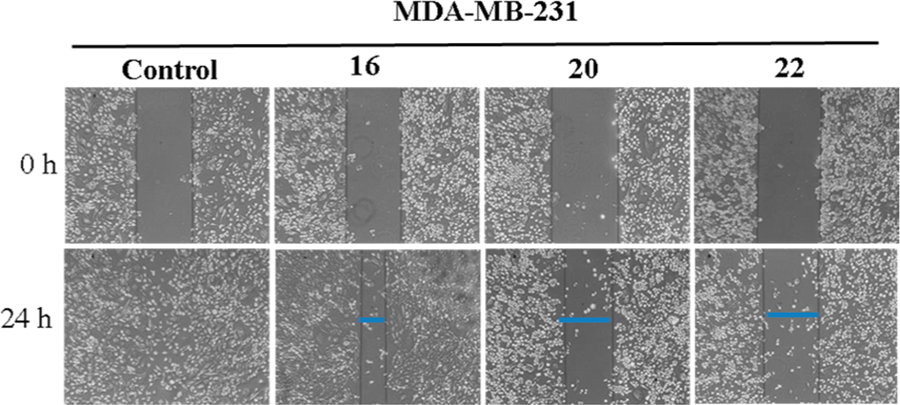

On the basis of previous studies with closely related compounds,8 we evaluated the inhibitory effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on cell migration, using the human metastatic breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 by wound-healing assay. Figure 4 shows that compounds 20 and 22 significantly inhibited migration of MDA-MB-231 cells compared to the control. At 24 h after cell monolayers were wounded, control cells had completely filled in the scratched area.

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on MDA-MB-231 cell migration: MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on Boyden chamber, grown to confluence and scratches made at experimental time zero. The cells were treated with indicated compounds (5 μM each) for 24 h. Representative photomicrographs of initial and final wounds are shown at 100× magnification.

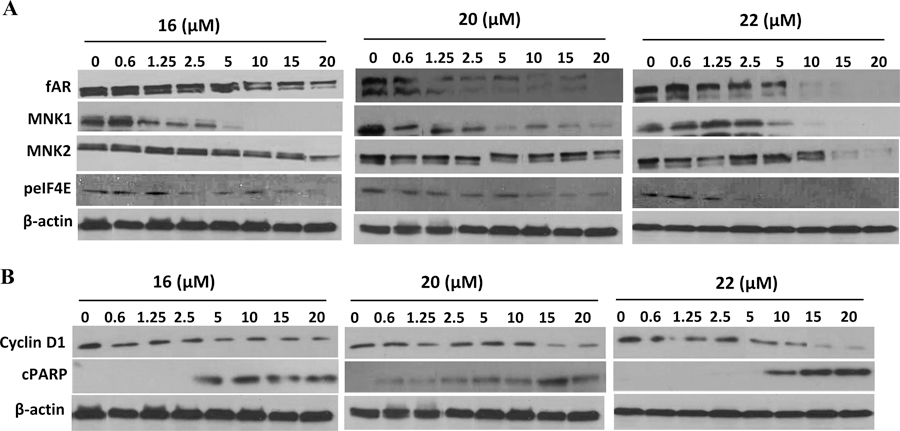

In Vitro Characterization of Compounds 16, 20, and 22 in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines.

Previously, we demonstrated that the antitumor activity of the early NRs in prostate cancer cells was due to simultaneous inhibition of the Mnk/eIF4E and androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathways.8b Similar to studies described above, we performed Western blot of lysates from LNCaP human prostate cancer cells treated with compounds 16, 20, and 22 or with vehicle (DMSO, negative control). Figure 5A shows that the three compounds significantly and in a dose-dependent fashion reduced the expressions of fAR, Mnk1, and Mnk2, with no noticeable effects on the expression of total eIF4E. In addition, the compounds caused significant depletion of oncogenic cyclin D1 and they each induced cleaved PARP (c-PARP), a reliable marker of apoptotic cell death (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on the expression of fAR, Mnk, peIF4E, cyclin D1, and cleaved PARP in LNCaP cells. Equal protein concentrations from LNCaP cells treated with 16, 20, and 22 at different concentrations (0.6–20 μM) for 24 h were separated by SDS–PAGE and Western blots probed with antibodies to fAR, Mnk1/2, peIF4E, cyclin D1, and cleaved PARP. Vehicle treated cells were included as a control, and all blots were reprobed for β-actin for loading control.

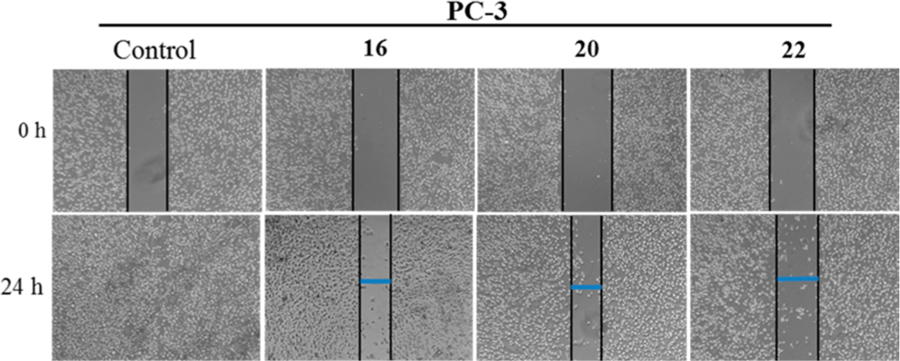

On the basis of previous studies with closely related compounds,8 we evaluated the inhibitory effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on cell migration, using the human metastatic PC cell line PC-3 by wound-healing assay. Figure 6 shows that the three compounds significantly inhibited migration of PC-3 cells compared to the control. At 24 h after cell monolayers were wounded, control cells had completely filled in the scratched area.

Figure 6.

Effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on PC-3 cell migration: PC-3 cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on Boyden chamber, grown to confluence and scratches made at experimental time zero. The cells were treated with indicated compounds (5 μM each) for 24 h. Representative photomicrographs of initial and final wounds are shown at 100× magnification.

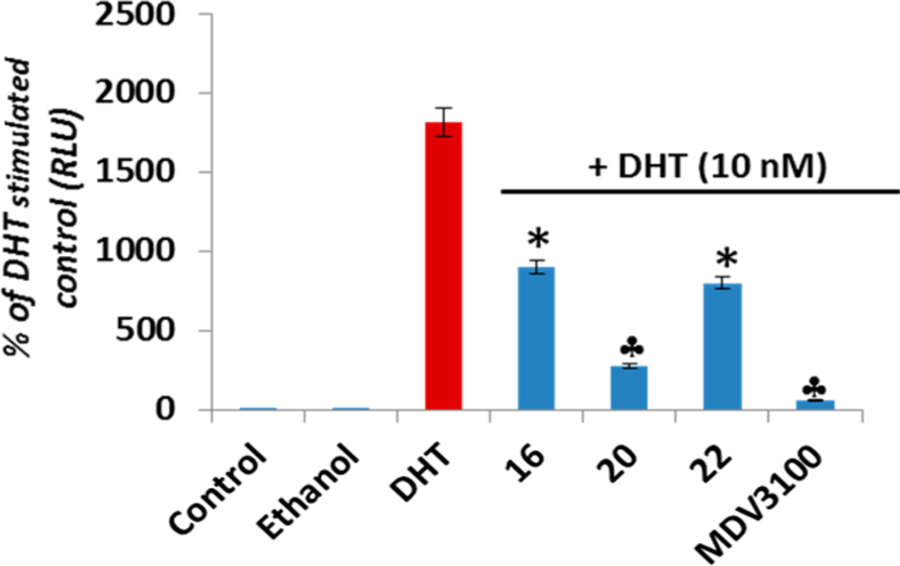

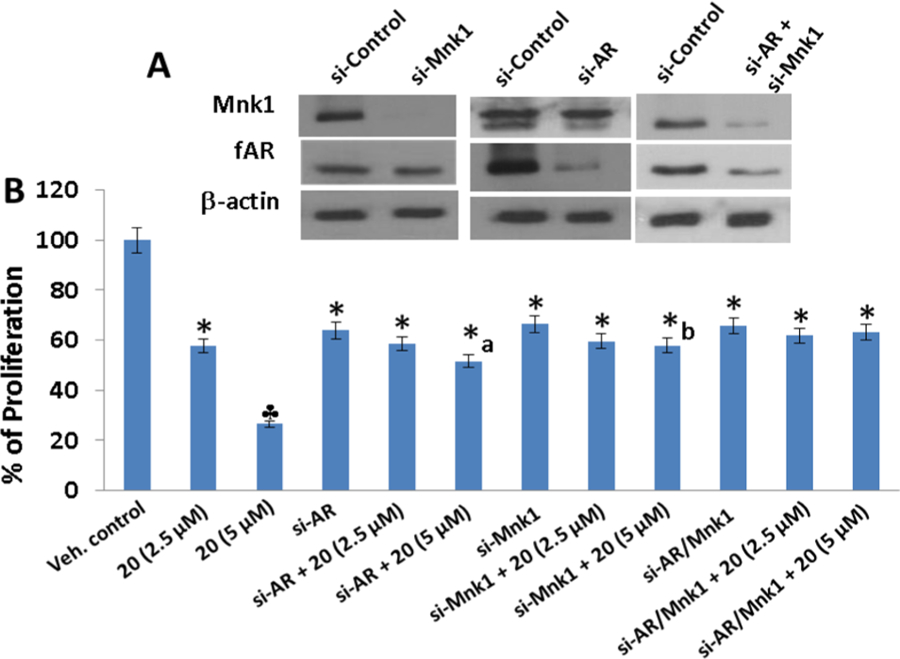

Since AR is a major driver of proliferation in PCa,21 we next examined the effect of these three compounds on AR transcriptional activity in LNCaP cells. As shown in Figure 7, 24 h exposure of LNCaP cells to lead NRs, 16, 20, and 22 (10 μM) resulted in a 2- to 4-fold dramatic inhibition of DHT induced AR transcriptional activity that was however less potent than that observed upon clinically available MDV3100 treatment. Of these leads, compound 20 was the most potent. To confirm whether AR and Mnk1 are the major anticancer targets of these compounds on LNCaP cells, we analyzed the percentage of cell survival in LNCaP cells by MTT assay following transient transfection with AR siRNA and/or Mnk1 siRNA for 18 h. Here, we present data for compound 20 which are identical to data for compounds 16 and 22. The efficiency of transfection was confirmed by Western blot analysis, wherein protein lysates obtained from the transfected cells after AR siRNA transfection showed a temporal decrease in total AR protein and cells transfected with Mnk1 siRNA showed a temporal decrease in the expression Mnk1 compared to scrambled (si-control) treated controls after 18 h of transfection (Figure 8A). Cells co-treated with AR and Mnk1 siRNA showed a remarkable decrease in the expression of both AR and Mnk1 compared to scrambled siRNA treated cells (Figure 8A). MTT assay revealed that transient transfections with AR and/or Mnk1 siRNA caused a considerable decrease (∼40%) in LNCaP cell viability compared to control (Figure 8B, compare bar 1 to bars 4, 7, and 10). Treatment of LNCaP cells (untransfected) with 5 μM concentration of compound 20 for 72 h showed a robust reduction in cell viability (bar 3). LNCaP cells harboring AR (bar 6) or Mnk1 (bar 9) knockdown also displayed a significant decrease in cell viability upon treatment with 5 μM of compound 20, compared to the AR and Mnk1 siRNA alone treated counterparts (bars 4 and 7, respectively). However, LNCaP cells with double knockdown of AR and Mnk1 genes (bar 12) did not show any significant decrease in cell viability upon agent treatment compared to cells co-treated with Mnk1 and AR siRNA (Figure 8B, bar 10). These results strongly suggest that Mnk1 and AR are prime targets of compounds 16, 20, and 22 and that loss of both these targets abolishes the potent growth-inhibitory effects mediated by these agents in LNCaP cells.

Figure 7.

Effects of compounds 16, 20, and 22 on DHT-induced AR transactivation in LNCaP cells: LNCaP cells dual transfected with ARR2-Luc and the Renilla luciferase reporting vector pRL-null and treated with 10 μM of specified compounds for 18 h in the presence of 10 nmol/L dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Control represents baseline activity without androgen stimulation. Androgen stimulated luciferase activity (luminescence) was measured in a Victor 1420 plate reader. The results are presented as the fold induction (i.e., the relative luciferase activity of the treated cells divided by that of control) normalized to that of Renilla: (*) P < 0.05; (clover) P < 0.01 compared with DHT alone treated cells.

Figure 8.

Effects of NRs on the viability of LNCaP cells transiently knocked-down for AR and/or Mnk1. (A) Western blot analysis of the expression of fAR and Mnk1 in LNCaP cells transfected with 100 nM of si-AR, si-Mnk1 and combinations for 18 h; (B) Effect of compound 20 on cell proliferation in LNCaP cells transfected with 100 nM of si-AR, si-Mnk1 and combinations as determined by MTT assay. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments and are represented as a bar graph after normalizing to control cells: (*) P < 0.05; (clover), P < 0.01 compared with vehicle treated control; (a) significantly different from si-AR treated cells, P < 0.05; (b) significantly different from si-Mnk1 treated cells, P < 0.05.

We note that although siRNA knockdown and treatment with compound 20 are expected to cause a similar percent of decrease in cell viability, the effect of siRNA on LNCaP cell proliferation depends on the treatment period and dose of siRNA used for transfection. In our study, we transfected LNCaP with 100 nM AR/Mnk1 siRNA for 18 h. siRNA transfection for 18–24 h typically results in only 30% of drop in cell viability.22 Only in cases where transfections are carried out for up to 96 h does a massive drop in cell proliferation of ∼12–15% (i.e., 85–88% growth inhibition) occur.23 Furthermore, the mechanisms by which AR/Mnk1 siRNA and compound 20 act are different. Whereas siRNA works at the level of transcription, compound 20 acts at the post-translational level, and hence even though compound 20 recapitulates AR/Mnk1 siRNA affects, the percentage of decrease in cell proliferation caused by the two agents (i.e., siRNA and NRs) are not alike.

Inhibition of Breast and Prostate Cancer Tumor Growth in Vivo.

To determine whether the anticancer effects exhibited by the lead compounds in cell cultures could be replicated in animal models, we conducted antitumor xenograft studies in two well-established aggressive models of human breast (MDA-MB-231) and prostate (CWR22Rv1) cancers. As noted above, although compounds 16, 20, and 22 are equipotent, we selected the last two compounds for in vivo studies based on their ease of synthesis, availability, and animal cost.

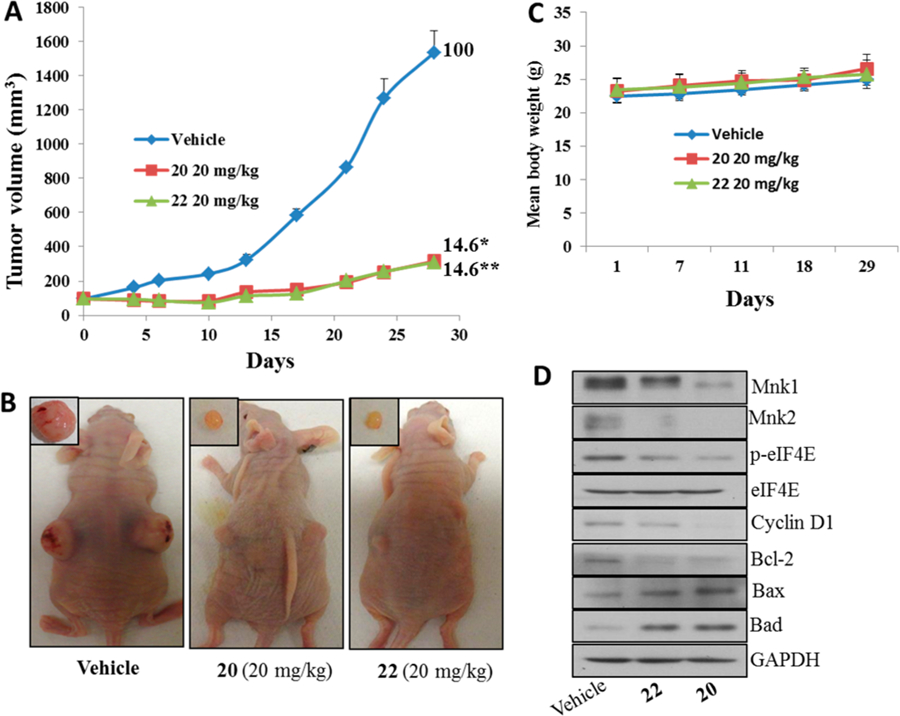

MDA-MB-231 Antitumor Efficacy Study.

First, we evaluated the in vivo antitumor efficacy of compounds 20 and 22 in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) xenografts that were administered intraperitoneally (ip) 20 mg/kg compound 20 or 22 5×/week over 28 days, which resulted in an 85.4% suppression of tumor growth. Indeed, the two compounds were equipotent (Figure 9A). Thus, the tumor growth inhibition, measured as %T/C = 14.6%, classified these compounds as highly efficacious according to the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) criteria.24 Tumor growth inhibition (%T/C), is defined as the ratio of the median tumor volume for the treated versus control group. Representative photos of the tumor-bearing mice in the control and the two treatment groups at termination of experiment (day 28) are presented in Figure 9B. Importantly, the mice in the treated group did not lose body weight (Figure 9C) and display any signs of toxicity, suggesting no apparent adverse events of the compounds.

Figure 9.

Compounds 20 and 22 suppress breast xenograft tumor growth in vivo. (A) Nude female mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors (n = 6/group) were treated with 20 or 22, administered ip 20 mg kg−1 day−1, 5 days per week for 28 days. %T/C values are indicated to the right of each growth curve, and the error bars are the SEM. Compounds 20 and 22 treatments, each significantly suppressed tumor growth (for 20, (*) p = 0.0001 and for 22, (**) p = 0.0001). (B) Representative photos of the tumor-bearing mice and excised tumors in the control and the two treatment groups at termination of experiment (day 28). (C) Body weight changes of the mice during the course of treatments. Animals were monitored for changes in body weight as a surrogate marker for toxicity in control and treatment groups. (D) Effect of compounds on the expression of proteins modulated by Mnk/eIF4E signaling. Total cell lysates in mice treated with vehicle, compounds 20 and 22, were prepared separately using RIPA buffer. Total protein (50 μg/well) from pooled samples (n = 6) was run on 10% SDS–PAGE and probed with antibodies for Mnk1, Mnk2, p-eIF4E, eIF4E, cyclin D1, breast cancer l-2, Bax, Bad, and GAPDH.

For the sake of comparison, with our early lead, compound 6 (based on ATRA scaffold)8 caused 97% suppression of MDA-MB-231 tumor growth (data not shown).25 These data suggest that compounds 20 and 22 can be classified as strong backup compounds in our novel retinamides drug discovery and development program. It is important to state here that additional antitumor studies are need in several breast cancer models in addition to rigorous pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and toxicology studies to identify the compound that will emerge as our Investigation New Drug (IND) candidate. It is also pertinent to note that our current clinical agent galeterone that emerged from our prostate cancer drug discovery program was a backup compound at the early stage of the development process.26 Galeterone has successfully completed phase II clinical trials in castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients and is scheduled to enter pivotal phase III clinical trials in the first half of this year.26

Molecular Analysis of Tumors.

To assess their in vivo mode of action, we evaluated the effects of compounds 20 and 22 on Mnk-1, peIF4E, and their downstream targets. As expected, tumors from mice treated with 20 or 22 showed depletion of Mnk1/2, peIF4E, cyclin D1, and antiapoptotic breast cancer l-2 (Bcl-2) with concomitant up-regulation of proapoptotic proteins, Bad and Bax (Figure 9D).

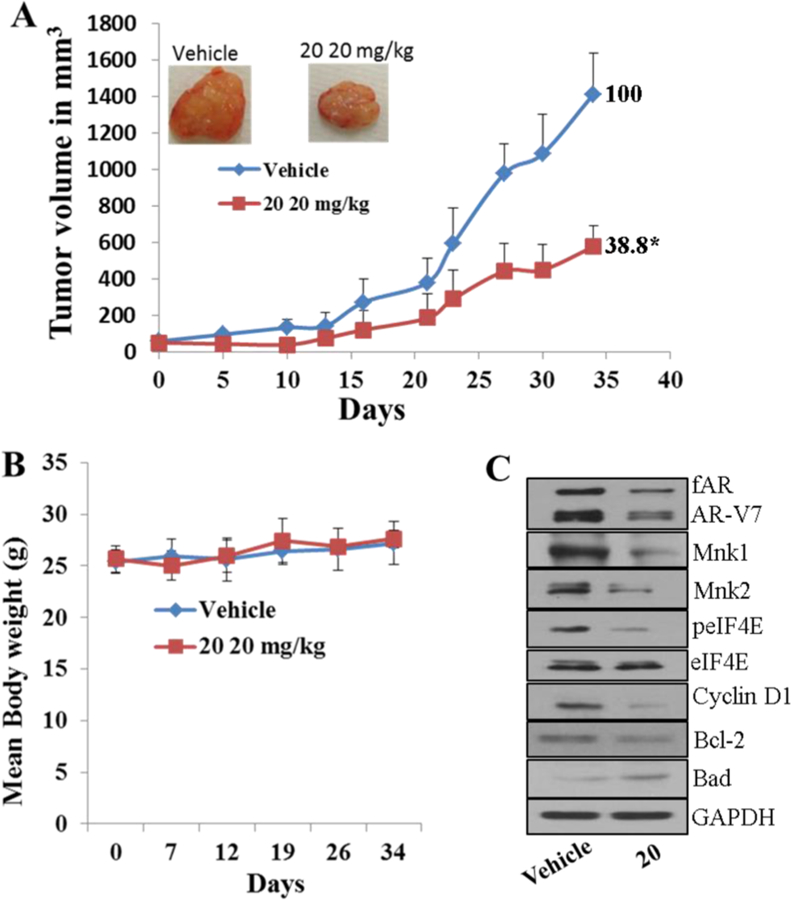

CWR22Rv1 Antitumor Efficacy Study.

Similarly, treatment of compound 20 to castrated mice bearing the aggressive CWR22Rv1 xenografts caused significant inhibition of tumor growth with %T/C value of 38.8, i.e., 61.2% suppression of tumor growth (Figure 10A). We also found that the body weights were comparable in mice from either vehicle control or treatment groups (Figure 10B), suggesting no apparent adverse effects of compound 20.

Figure 10.

Compound 20 suppresses prostate xenograft tumor growth in vivo. (A) Castrated SCID male mice bearing CWR22Rv1 xenograft tumors (n = 6/group) were treated with 20, administered ip 20 mg kg−1 day−1, 5 days per week for 28 days. %T/C values are indicated to the right of each growth curve, and the error bars are the SEM. Compound 20 treatment significantly suppressed tumor growth ((*) p = 0.0001). (B) Body weight changes of the mice during the course of treatments. Animals were monitored for changes in body weight as a surrogate marker for toxicity in control and treatment groups. (C) Effect of compounds on the expression of proteins modulated by AR and Mnk/eIF4E signaling. Total cell lysates in mice treated with vehicle, 20, and 22 were prepared separately using RIPA buffer. Total protein (50 μg/well) from pooled samples (n = 6) was run on 10% SDS–PAGE and probed with antibodies for fAR, AR-V7, Mnk1, Mnk2, p-eIF4E, eIF4E, cyclin D1, breast cancer l-2, Bad, and GAPDH.

Molecular Analysis of Tumors.

To assess their in vivo mode of action, we evaluated the effects of compounds 20 on fAR, AR-V7, Mnk-1, peIF4E, and their downstream targets. As expected, tumors from mice treated with compounds 20 showed depletion of fAR, AR-V7, Mnk1/2, peIF4E, cyclin D1, and antiapoptotic breast cancer l-2 (Bcl-2) with concomitant up-regulation of proapoptotic protein, Bad (Figure 10C).

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has shown for the first time that high anticancer activities can be retained in C-4 heteroaryl retinamides based on the rarely utilized 13-cis-retinoic acid scaffold. In this study, we describe a series of novel C-4 heteroaryl 13-cis-retinamides that degrade Mnk1 and Mnk2 with concomitant suppression of oncogenic eIF4E phosphorylation in a variety of human breast and prostate cancer cell lines. In addition, the compounds also modulate activities of full-length and splice variant androgen receptors (fAR and AR-V7) via AR antagonism and AR degradation in prostate cancer cells. Three lead compounds, including 16, 20, and 22, were identified. Of these compounds, 20 and 22 exhibited equipotent and strong suppression of the growth of aggressive human triple negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts. Compound 20 also proved to be very effective at inhibiting the growth of castration-resistant CWR22Rv1 human prostate tumor xenografts. These impressive in vitro and in vivo antibreast and antiprostate cancers activities make compounds 20 and 22 strong candidates for further development as potential new drugs for the treatments of breast and prostate cancers in humans. In addition, given the implication of Mnk1/2-eIFE axis in the initiation and progressions of all types of solid tumors27 and hematologic cancers,28 these and related retinamides warrant evaluation in other types of cancers.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry.

General.

All the materials listed below were of research grade or spectrophotometric grade in the highest purity commercially available from Sigma-Aldrich. Column chromatography was performed on silica (230–400 mesh, 60 Å) from Silicycle. Silica gel plates (Merck F254) were used for thin layer chromatography (TLC) and were developed with mixtures of ethyl acetate (EtOAc)/petroleum ether or CH2Cl2/methanol (MeOH) unless otherwise specified and were visualized with 254 and 365 nm light and I2 or Br2 vapor. Petroleum ether refers to light petroleum, bp 40–60 °C. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 using a Brüker 400 MHz NMR instrument, and chemical shifts are reported in ppm on the δ scale relative to tetramethylsilane. High resolution mass spectra were obtained on a Bruker 12 T APEX-Qe FTICR-MS instrument by positive ion ESI mode by Susan A. Hatcher, Facility Director, College of Sciences Major Instrumentation Cluster, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA. Melting points were determined with Fischer Johns melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Purities of the compounds were determined by Waters UPLC BEH C18 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm column using a solvent gradient system of ammonium acetate buffer/acetonitrile/methanol (100 → 0, 0 → 100, and 0 → 10, respectively) over a period of 10 min. The purities of all final compounds were determined to be at least 95% pure by a combination of UPLC, NMR, and HRMS.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (11).

In a 250 mL round-bottomed flask (RBF) equipped with a magnetic stirrer, 13-cis-retionoic acid (10) (5 g, 16.64 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (30 mL) and benzene (100 mL). While stirring, trimethylsilyldiazomethane solution 2.0 M in hexanes (3.730 g, 32.68 mmol) was added dropwise very slowly, and reaction was monitored by the gas evolution on the oil bubbler. The reaction mixture was concentrated to give an oily yellow crude product. Purification by flash column chromatography [FCC; petroleum ether/EtOAc (9:1)] afforded compound 11 as a yellow solid. Yield, 4.32 g (83%); mp, 38–40 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.77 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.32–6.21 (m, 2H), 6.15 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 5.64 (s, 1H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 2.03 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.65–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.47 (dd, J = 7.7, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.8, 151.3, 139.8, 137.6, 137.4, 132.2, 130.3, 130.0, 129.2, 128.5, 128.3, 116.0, 77.3, 77.0, 76.7, 50.9, 39.6, 34.2, 33.1, 28.9, 21.7, 20.9, 19.2, 12.8.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-oxocyclohex-1-en-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (12).

In a 500 mL volumetric flask, 11 (4.00 g, 12.7 mmol) and MnO2 (100 g, 1150 mmol) were added into 100 mL of dichloromethane. The mixture was allowed to stir on an Innova 2000 platform shaker at 200 rpm for 12 h. Filtration was done through a pad of Celite and the organic reaction mixture concentrated to give a thick yellow oil. This was adsorbed on silica (50 g) and packed on a column where elution was done by gravity with a solvent system of petroleum ether/EtOAc (9:1) to yield compound 12 as a yellow solid. Yield, 2.80 g (68%); mp, 83–85 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.85 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (dd, J = 12.5, 7.6 Hz, 3H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 4.12 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 2.51 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.86 (s, 3H), 1.26 (t, 2H), 1.19 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 199, 166.6, 160.7, 150.7, 140.6, 138.1, 133.6, 131.4, 131.2, 130.1, 125.8, 117.2, 51.0, 37.4, 35.7, 34.2, 27.6, 21.0, 13.7.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 9-(3-Hydroxy-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (13).

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask, 12 (2.50 g, 7.61 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (20 mL) and crystilline sodium borohydride (0.45 g, 11.9 mmol) was added slowly and left to stir at room temparature for 1 h where TLC analysis shows exhaustion of the starting material. Reaction mixture was diluted with water (25 mL), extraction done with CH2Cl2 (2 × 20 mL). Organic portions were mixed and concentrated to give a thick brownish oil. This was adsorbed on silica and packed on a column where elution was done via gravity using a solvent system of petroleum ether/EtOAc (8:2) to yield compound 13 as a yellow oil. Yield, 2.01 g (80%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.79 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.03–6.92 (m, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 5.66 (s, 1H), 4.01 (s, 1H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.90 (ddd, J = 11.5, 6.9, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.76–1.57 (m, 2H), 1.43 (ddd, J = 13.2, 7.3, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 1.02 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 151.1, 141.6, 139.2, 138.4, 132.0, 131.1, 130.2, 129.8, 127.5, 116.4, 70.2, 50.9, 34.8, 34.5, 29.0, 27.5, 20.9, 18.6, 12.8.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (14).

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask 13 (1.90 g, 5.75 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitrile (25 mL) followed by addition of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) (1.21 mg, 7.47 mmol). On adding CDI, reaction mixture was seen to turn from yellow to dark red with evolution of gas. After 1 h, TLC analysis showed exhaustion of starting material, and the reaction mixture was therefore concentrated. Water (20 mL) was added, and extraction was effected using CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic portion was concentrated, adsorbed on silica, and loaded on a column where elution was done via gravity with a solvent system of methanol/CH2Cl2 (0.5:9.5) to yield compound 14 as a red viscous oil. Yield, 1.50 g 69%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.80 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 7.00–6.87 (m, 2H), 6.33–6.17 (m, 3H), 5.67 (s, 1H), 4.54 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.82 (dt, J = 35.3, 18.6 Hz, 2H), 1.61 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 3H), 1.57 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 1.50 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 1.17–1.04 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 150.9, 144.8, 139.2, 138.6, 136.8, 131.7, 131.7, 130.2, 129.2, 126.5, 125.0, 118.1, 116.7, 77.3, 77.2, 77.0, 76.7, 58.0, 53.4, 51.0, 34.7, 34.6, 29.0, 28.1, 27.8, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H32N2O2Na+, 403.2355. Found: 403.2357.

General Procedure A.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona −2,4,6,8-tetraenoic Acid (15).

In a 25 mL round-bottom flask, 14 (1.00 g, 2.62 mmol) was dissolved in methanol/water (9:1), and potassium hydroxide (final reaction concentration of 2 M) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir under reflux for 4 h after which the reaction mixture was concentrated and diluted with water (25 mL). The pH of the resulting solution was adjusted to 7. On adjusting the pH, compound 15 precipitated out of solution as a yellow solid, filtered, and washed with cold ether (2 × 20 mL). This was used as is without further purification in the subsequent step. Yield, 0.60 g (63%); mp, 151–153 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.07 (s, 1H), 7.78–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.17–6.87 (m, 3H), 6.32 (q, J = 16.2 Hz, 3H), 5.64 (s, 1H), 4.73 (s, 1H), 2.12–1.94 (m, 6H), 1.84–1.68 (m, 2H), 1.50 (s, 3H), 1.48 (s, 2H), 1.09 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 167.5, 150.6, 143.9, 139.5, 139.0, 137.3, 132.2, 131.9, 130.3, 128.6, 127.2, 125.8, 118.8, 118.2, 66.8, 35.1, 34.7, 29.1, 28.3, 28.1, 20.9, 18.8, 13.0. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H30N2O2Na+, 389.2199. Found: 389.2202

General Procedure B.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-3,7-dimethyl-N-phenylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (16).

To a 25 mL round-bottom flask, 15 (0.2 g, 0.546 mmol), aniline (0.056 g, 0.601 mmol), EDC (0.208 g, 1.09 mmol), HOBT (0.147 g, 1.09 mmol), and DIPEA (0.706 g, 5.46 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (3 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 12 h, concentrated, diluted with water (50 mL), and extracted using CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic portions were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to give the crude product as a reddish oil. Purification by gravity chromatography on silica using 10% EtOAc in petroleum ether gave 16 as a yellow powder. Yield, 0.16 g (64%); mp, 166–168 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 3H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (s, 3H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 7.14–7.06 (m, 2H), 6.94 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.3 Hz, 2H), 6.31 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (q, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.92 (s, 1H), 1.85 (s, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.57 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 4H), 1.50 (s, 1H), 1.37–1.26 (m, 1H), 1.17–1.02 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.6, 154.1, 146.9, 145.2, 139.5, 137.4, 136.5, 132.3, 131.1, 130.4, 130.2, 128.4, 125.7, 124.5, 121.7, 120.9, 118.5, 115.7, 53.4, 36.5, 31.4, 29.0, 27.7, 24.9, 20.8, 18.8, 12.7. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C29H35N3ONa+, 464.2672. Found: 464.2674.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (17).

Compound 17 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.113 g (47%); mp, 111–113 °C;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.85 (dd, J = 21.5, 10.1 Hz, 3H), 6.27–6.08 (m, 2H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 3.47 (s, 1H), 2.09 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (s, 2H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, J = 22.5 Hz, 5H), 1.85 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 1.65 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 1.56 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 3H), 1.50 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.31 (dd, J = 26.4, 14.7 Hz, 1H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.6, 154.1, 146.9, 145.2, 139.5, 137.4, 136.5, 132.3, 131.1, 130.4, 130.2, 128.4, 125.7, 124.5, 121.7, 120.9, 118.5, 115.7, 53.4, 36.5, 31.4, 29.0, 27.7, 24.9, 20.8, 18.8, 12.7. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C29H35N3O2Na+, 480.2621. Found: 480.2624.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (18).

Compound 18 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.080 g (32%); mp, 136–138 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.16–6.79 (m, 7H), 6.32 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.23 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 2.09 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.85 (s, 2H), 1.59 (s, 4H), 1.52 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 1.11 (d, J = 21.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.9, 149.9, 149.0, 144.9, 139.2, 138.8, 136.7, 131.9, 130.2, 129.0, 126.7, 126.5, 126.1, 125.0, 121.8, 120.1, 119.4, 118.3, 58.0, 34.7, 34.6, 29.0, 28.1, 27.8, 21.1, 18.8, 12.9. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C29H35N3O2Na+, 480.2621. Found: m/z = 480.2626.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(4-fluorophenyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (19).

Compound 19 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.151 g (63%); mp, 123–125 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 21.5, 10.1 Hz, 3H), 6.41 (m, 2H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 3.47 (s, 1H), 2.09 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (s, 2H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, J = 22.5 Hz, 5H), 1.85 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 1.65 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 1.56 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 3H), 1.50 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.31 (dd, J = 26.4, 14.7 Hz, 1H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.7, 153.1, 146.8, 145.2, 139.5, 137.4, 135.5, 132.3, 131.0, 130.4, 130.2, 127.4, 125.7, 124.5, 122.7, 120.9, 116.5, 115.7, 53.4, 35.5, 31.4, 29.0, 27.7, 24.9, 20.8, 18.8, 12.7. Calcd for C29H34FN3ONa+, 482.2578. Found: m/z = 482.2580.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(3-fluorophenyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (20).

Compound 20 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.143 g (59%); mp, 119–121 °C;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.92 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (dd, J = 33.6, 17.3 Hz, 3H), 7.17 (s, 1H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 7.03–6.88 (m, 2H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 6.34–6.14 (m, 3H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 2.05 (d, J = 32.2 Hz, 6H), 1.85 (s, 1H), 1.69 (s, 3H), 1.52 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 2H), 1.29 (s, 1H), 1.10 (d, J = 19.9 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.4, 161.8, 149.0, 144.9, 139.9, 139.2, 138.4, 136.8, 136.2, 131.9, 131.4, 131.0, 130.4, 130.0, 129.9, 129.1, 126.4, 125.0, 119.5, 118.2, 58.0, 34.7, 34.6, 29.03, 28.1, 27.8, 21.0, 18.8, 12.8. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C29H34FN3ONa+, 482.2578. Found: 482.2580.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-benzyl-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (21).

Compound 21 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.124 g (52%); mp, 79–81 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.89 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 7.71–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.37 (dd, J = 14.1, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.28 (m, 5H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 6.92 (s, 1H), 6.28 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (s, 1H), 5.58 (s, 1H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.49 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.16–2.08 (m, 1H), 2.06–1.97 (m, 6H), 1.82 (dd, J = 8.8, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 1.61–1.53 (m, 3H), 1.52–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.15 (d, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.2, 146.8, 146.0, 139.5, 138.4, 137.5, 136.1, 132.3, 130., 130.38, 128.7, 127.8, 127.4, 126.0, 125.6, 124.1, 123.8, 120., 119.0, 110.1, 58.7, 43.5, 34.7, 34.3, 29.0, 28.0, 27.7, 20.8, 18.8, 12. Calcd for C30H37N3ONa+, 478.2828. Found: 478.2829.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (22).

Compound 22 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.161 g (62%); mp, 139–141 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.66 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 6.87–6.77 (m, 3H), 6.17 (dd, J = 18.0, 10.5 Hz, 3H), 5.94 (s, 1H), 5.62 (s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 4.48–4.29 (m, 2H), 2.14 (s, 1H), 1.97 (t, J = 6 Hz, 6H), 1.85 (s, 2H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.53 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 2H), 1.10 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.4, 156.9, 145.6, 145.2, 140.0, 137.2, 136.2, 132.5, 131.0, 129.8, 129.3, 128.9, 128.2, 125.5, 124.4, 121.1, 118.8, 115.8, 58.5, 43.2, 34.6, 34.4, 29.0, 28.0, 27.8, 20.5, 19.1, 12.7. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C30H37N3O2Na+, 494.2777. Found: 494.2780.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(4-fluorobenzyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (23).

Compound 23 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.119 g (47%); mp, 93–95 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.95–7.84 (m, 2H), 7.74–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 6.93 (ddd, J = 26.9, 16.4, 10.0 Hz, 4H), 6.22 (dt, J = 22.8, 13.7 Hz, 4H), 5.86 (s, 1H), 5.59 (s, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.18–2.07 (m, 1H), 2.05–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.83 (dd, J = 9.1, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.53–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.15–1.06 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.2, 164.8, 163.4, 150.6, 147.0, 146.7, 139.5, 137.6, 134.3, 132.2, 130.9, 130.4, 129.5, 129.4, 125.6, 123.9, 123.9, 122.0,115.6, 115.4, 110.1, 58.8, 42.7, 34.7, 34.2, 29.0, 28.0, 27.7, 20.8, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C30H36FN3ONa+, 496.2734. Found: 496.2735.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(3-fluorobenzyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (24).

Compound 24 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.137 g (54%); mp, 96–98 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.15–6.84 (m, 7H), 6.28 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.26–6.12 (m, 2H), 5.91 (s,1H), 5.60 (s, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.49 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.19–2.07 (m, 1H), 2.02 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 6H), 1.83 (dd, J = 9.5, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.50 (dd, J = 15.4, 9.4 Hz, 2H), 1.16–1.05 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.2, 164.2, 161.7, 147.2, 145.9, 141.2, 139.5, 137.7, 132.2, 130.9, 130.5, 130.1, 125.7, 124.0, 123.2, 119.7, 114.6, 110.0, 58.6, 42.8, 34.7, 34.3, 29.0, 27.9, 27.7, 20.8, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd. for C30H36FN3ONa+, 496.2734. Found: 496.2735.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)-N-(4-hydroxyphenethyl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (25).

Compound 25 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.161 g (60%); mp, 126–128 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (s, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.85–6.80 (m, 3H), 6.23–6.16 (m, 4H), 5.60 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 5.54 (s, 1H), 4.55 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.57–3.51 (m, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.17–2.07 (m, 1H), 1.98 (dd, J = 9.1, 5.3 Hz, 6H), 1.88–1.77 (m, 2H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.51 (dd, J = 14.0, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 1.10 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 155.3, 145.9, 145.4, 139.7, 137.4, 132.2, 130.7, 130.1, 129.7, 125.9, 125.6, 124.0, 124.0, 121.0, 119.0, 115.7, 110.2, 58.6, 40.7, 34.7, 34.3, 29.1, 28.0, 27.6, 20.7, 19.0, 12.7. Calcd for C31H39N3O2Na+, 508.2934. Found: 508.2935.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)oxy)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (26).

In a 50 mL flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, THF (10 mL) was added, and the temperature was lowered to −78 °C. Sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide solution (1 M in THF, 9.2 mL, 9.24 mmol) was added to the chilled THF. To this, 12 (2.0 g, 6.09 mmol) dissolved in 10 mL of THF was added very slowly and allowed to stir for 45 min at this temparature. During this time, reaction mixture was seen to turn from yellow color to brick red. N-(5-Chloro-2-pyridyl)bistrifluoromethanesulfonimide (3.58 g, 9.12 mmol) dissolved in 10 mL of THF was added very slowly to the reaction mixture. Reaction mixure was then allowed to stir at this temperature for an additional 3 h. Reaction mixture was thereafter poured quickly into an aqueous solution of NaHCO3 and extracted using EtOAc. Purification by flash chromatography on silica using 10% EtOAc in petroleum ether gave 26 as a yellow powder. Yield, 2.03 g (75%); mp, 98–100 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.82 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.37–6.11 (m, 3H), 5.73 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 3H), 2.24 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 2.08 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 3H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.90 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 150.8, 147.9, 144.5, 139.1, 138.5, 132.5, 131.6, 130.6, 125.4, 122.0, 120.1, 116.9, 113.8, 51.0, 37.7, 34.5, 26.3, 20.9, 14.4, 12.7. Calcd for C22H27F3O5SNa+, 483.1423. Found: 483.1422.

General Procedure C.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 9-(3′-Methoxy-2,4,4-trimethyl-4,5-dihydro[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (27).

In a 50 mL flask, CeCO3 (2.11 g, 6.47 mmol) dissolved in I mL was added followed by 10 mL of dioxane. The solution was flushed with N2 for 1 h. 19 (1.92 g, 4.31 mmol), 3-methoxyphenylboronic acid (0.787 g, 5.18 mmol), and Pd(Ph3)4 (5% weight of 18) were added into the flask, and the reaction mixture was allowed to reflux at 85 °C for 12 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated, and brine was added. Extraction was done using EtOAc and the organic extracts were concentrated to give a crude product as a dark yellow oil. Purification by gravity chromatography on silica using 5% EtOAc in petroleum ether gave 27 as a red oil. Yield, 1.60 g (88%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.80 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.21 (m, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.84–6.76 (m, 2H), 6.73 (dd, J = 2.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 2H), 6.32 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.65 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 1H), 3.81 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 3H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 2.18 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.07 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.10 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 159.2, 151.1, 143.6, 141.6, 140.9, 139.5, 137.4, 132.1, 131.2, 129.7, 128.8, 127.7, 127.4, 124.6, 120.9, 116.3, 114.0, 111.9, 55.2, 50.9, 39.6, 34.3, 26.6, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C28H34O3Na+, 441.2400. Found: 441.24.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyridin-3-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (28).

Compound 28 was synthesized using general procedure C using the respective boronic acid. Yellow powder. Yield, 1.201 g (69%); mp, 77–79 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54–8.44 (m, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.27–7.22 (m, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 3H), 5.79 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (s, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 3H), 2.22 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.08 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 151.1, 149.2, 147.8, 141.6, 139.3, 138.4, 137.8, 137.6, 135.6, 132.0, 131.4, 129.9, 126.9, 126.5, 126.3, 122.7, 116.4, 50.9, 39.5, 34.3, 26.7, 26.6, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C26H31NO2Na+, 412.2247. Found: 412.2247.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-Methyl 3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoate (29).

Compound 29 was synthesized using general procedure C using the respective boronic acid. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.896 g (60%); mp, 162–164 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 3H), 5.85 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.67 (s, 1H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 2.25 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.08 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 2.04 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 157.0, 155.8, 151.0, 142.4, 139.0, 138.2, 135.4, 135.2, 131.8, 131.7, 130.1, 128.0, 126.5, 125.2, 116.6, 50.9, 39.4, 34.3, 26.6, 26.6, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C25H30N2O2Na+, 413.2199. Found: 413.2199.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-9-(3′-Methoxy-2,4,4-trimethyl-4,5-dihydro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoic Acid (30).

Compound 30 was synthesized using the general procedure A. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.621 g (62%); mp, 194–196 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.76 (t, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.82–6.75 (m, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 6.39–6.31 (m, 3H), 5.76 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 3.81 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 3H), 2.18 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.03 (s, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 159.2, 151.1, 143.6, 141.6, 140.9, 139.5, 137.4, 132.1, 131.2, 129.7, 128.8, 127.6, 127.4, 124.6, 120.9, 116.3, 113.9, 111.9, 55.2, 50.9, 39.6, 34.3, 26.7, 26.6, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C27H32O3Na+, 427.2243. Found: m/z = 427.2246.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyridin-3-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoic Acid (31).

Compound 31 was synthesized using general procedure A. Orange powder. Yield, 0.584 g (48%); mp, 113–116 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54–8.44 (m, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 3H), 5.78 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (s, 1H), 2.21 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (t, J = 3.4 Hz, 3H), 2.04 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 1.70 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.3, 152.5, 148.6, 147.2, 141.7, 139.5, 138.2, 137.8, 136.1, 132.3, 131.5, 129.9, 127.1, 126.6, 126.4, 122.9, 116.3, 77.3, 77.2, 77.0, 76.7, 39.5, 34.3, 26.6, 21.1, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C25H29NO2Na+, 398.2090. Found: 398.2090.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-3,7-Dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenoic Acid (32).

Compound 32 was synthesized using general procedure A. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.673 g (70%); mp, 111–113 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.13 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.41–6.29 (m, 3H), 5.85 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 2.25 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 3H), 2.04 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 3H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.7, 156.8, 155.8, 153.0, 142.4, 139.5, 138.2, 135.5, 135.1, 132.4, 131.7, 130.0, 128.2, 126.7, 125.3, 116.0, 67.1, 39.4, 34.3, 26.6, 21.1, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C24H28N2O2Na+, 399.2042. Found: 399.2043.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxybenzyl)-9-(3′-methoxy-2,4,4-trimethyl-4,5-dihydro[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (33).

Compound 33 was synthesized using general procedure B as a red oil. Yield, 0.124 g (45%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.21–7.14 (m, 2H), 6.83–6.69 (m, 5H), 6.35–6.13 (m, 4H), 5.77–5.52 (m, 4H), 4.92 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H), 2.18 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H), 2.02 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 1.75 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 3H), 1.10 (dd, J = 11.3, 5.9 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.5, 159.2, 155.5, 149.1, 147.0, 143.7, 141.6, 141.0, 138.6, 137.6, 135.8, 132.3, 131.4, 130.8, 130.1, 129.3, 128.8, 127.5, 126.9, 124.5, 120.9, 119.5, 115.6, 113.9, 111.9, 55.2, 43.0, 39.5, 36.6, 34.3, 26.6, 20.8, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C34H39NO3Na+, 532.2822. Found: 532.2821.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxyphenethyl)-9-(3′-methoxy-2,4,4-trimethyl-4,5-dihydro[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-3,7-dimethylnona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (34).

Compound 34 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.104 g (40%); mp, 102–105 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.76 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (dd, J = 14.0, 5.4 Hz, 4H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 6.27 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 5.46 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 2H), 5.09 (s, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.53 (dd, J = 12.9, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.18 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 6H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 3H), 1.10 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 200.9, 191.8, 166.6, 159.2, 154.4, 146.5, 143.7, 141.6, 141.0, 138.5, 137.6, 131.4, 130.8, 130.7, 130.1, 129.8, 128.8, 127.4, 126.8, 125.2, 124.5, 120.9, 119.9, 115.5, 113.9, 111.9, 109.3, 55.2, 40.7, 39.5, 34.8, 34.3, 26.6, 20.8, 18.8, 12.7. Calcd for C35H41NO3Na+, 546.2978. Found: 546.2977.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-3,7-Dimethyl-N-phenyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyridin-3-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (35).

Compound 35 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.149 g (62%); mp, 102–104 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.51 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 3H), 7.17 (s, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 15.1, 11.4 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 5.79 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 2.21 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.71 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.8, 158.2, 149.2, 148.4, 147.8, 141.6, 138.8, 138.4, 137.9, 137.6, 135.6, 131.6, 131.3, 130.2, 128.9, 126.7, 126.3, 122.7, 39.5, 34.3, 26.6, 20.9, 18.8, 12.8. Calcd for C31H34N2ONa+, 473.2563. Found: 473.2563.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxybenzyl)-3,7-dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyridin-3-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (36).

Compound 36 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.104 g (80%); mp, 124–126 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.52–8.42 (m, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (q, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H), 6.31–6.22 (m, 3H), 5.79 (dd, J = 12.5, 7.8 Hz, 2H), 5.57 (s, 1H), 4.41 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 6H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.10 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 165.8, 156.7, 148.9, 148.2, 145.3, 141.8, 138.5, 138.3, 138.2, 137.4, 135.9, 132.2, 131.5, 130.2, 129.1, 126.4, 126.3, 126.3, 123.6, 123.5, 121.5, 118.8, 115.4, 111.0, 41.9, 34.3, 26.8, 20.9, 19.0, 12.9. Calcd for C32H36N2O2Na+, 503.2669. Found: 503.2667.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxyphenethyl)-3,7-dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyridin-3-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (37).

Compound 37 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.135 g (51%); mp, 110–112 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (dd, J = 15.3, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.30 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 2H), 6.27 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.53 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (s, 1H), 3.53 (dd, J = 12.9, 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.00 (s, 6H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 154.8, 148.9, 147.5, 146.2, 141.8, 138.3, 138.2, 138.1, 137.8, 135.8, 131.7, 130.5, 130.4, 129.8, 126.3, 126.3, 126.2, 122.9, 120.1, 115.6, 40.7, 39.4, 34.8, 34.3, 26.6, 20.7, 18.9, 12.7. Calcd for C33H38N2O2Na+, 517.2803. Found: 517.2824.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-3,7-Dimethyl-N-phenyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (38).

Compound 38 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.116 g (48%); mp, 105–107 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (s, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (dd, J = 18.8, 11.4 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (dd, J = 15.4, 11.5 Hz, 1H), 6.37–6.27 (m, 2H), 5.84 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 5.69 (s, 1H), 2.24 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 2.01 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 3H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 156.9, 156.8, 155.8, 155.3, 146.6, 142.7, 142.6, 138.6, 138.3, 138.1, 137.9, 135.5, 135.2, 132.1, 130.7, 130.5, 129.4, 127.9, 125.9, 125.1, 120.0, 115.5, 39.4, 34.3, 26.5, 20.7, 18.9, 12.7. Calcd for C30H33N3ONa+, 474.2515. Found: 474.2515.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxybenzyl)-3,7-dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (39).

Compound 39 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.154 g (60%); mp, 145–147 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.84 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.28 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 5.85 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 5.70 (d, J = 11.4 Hz, 1H), 5.57 (s, 1H), 4.41 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.24 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 2.02 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H), 1.72 (s, 3H), 1.10 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 156.9, 156.8, 155.8, 155.3, 146.6, 142.7, 142.6, 138.6, 138.3, 138.1, 137.9, 135.5, 135.2, 132.1, 130.7, 130.5, 129.4, 127.9, 125.9, 125.1, 120.0, 115.5, 43.0, 39.4, 34.3, 26.5, 20.7, 18.9, 12.7. Calcd for C31H35N3O2Na+, 504.2621. Found: 504.2620.

(2Z,4E,6E,8E)-N-(4-Hydroxyphenethyl)-3,7-dimethyl-9-(2,6,6-trimethyl-3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)cyclohexa-1,3-dien-1-yl)-nona-2,4,6,8-tetraenamide (40).

Compound 40 was synthesized using general procedure B. Yellow powder. Yield, 0.161 g (61%); mp,115–117 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.61 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.32–6.21 (m, 2H), 5.84 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 3.53 (dd, J = 12.9, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.24 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 6H), 1.74 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H), 1.13–1.02 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 156.8, 155.8, 154.7, 146.3, 142.6, 138.5, 138.0, 135.5, 135.2, 132.0, 130.6, 130.5, 130.4, 129.8, 128.0, 125.9, 125.0, 120.2, 115.6, 40.7, 39.4, 34.8, 34.3, 26.6, 20.7, 18.8, 12.7. Calcd for C32H37N3O2Na+, 518.2777. Found: 518.2778.

Biology Experiments.

Cell Culture and Western Blotting.

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and SKBR-3 human breast cancer cells and LNCaP, PC-3, and CWR22Rv1 human prostate carcinoma cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media (Gibreast Cancero-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Western blotting was done as mentioned previously,8,13b using the following antibodies: AR, Bad, Bax, breast cancer l-2, eIF4E, Mnk1, Mnk-2, N-cadherin, PARP, peIF4Eser209 purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA. Anti-Mnk2 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and normal rabbit IgG, cyclin D1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA.

Cell Proliferation Analysis.

Cells were plated (2500 cells/well) in 96-well plates and treated with or without specified compounds as described previously.8a,12b

Wound Healing Assay.

Wound healing assay was conducted as described previously using MDA-MB-231 and PC-3 cells following treatment with 5 μM NRs for 24 h.8a,29

siRNA Transfection and Luciferase Assay.

siRNA (100 nM) was transfected into LNCaP cells using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s protocol. Protein silencing was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. For cell growth assay experiments, transfection complex was removed after 18 h and cells were washed twice with PBS and replaced with growth medium. 24 h later drug was added and harvested after 72 h. For Western blot experiment, transfection complexes were washed off after 18 h and replaced with phenol free media for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 20 μM compound 20 for an additional 24 h, and cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer.8b,30 Luciferase assay was conducted in LNCaP cells using the dual luciferase kit (Promega) as described earlier.8b,13b

In Vivo Antitumor Studies.

All animal studies were performed according to the guidelines and approval of the Animal Care Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. Female athymic nude mice or male SCID (Charles Rivers Laboratories or UMB facilities) at 4–6 weeks of age were maintained in a pathogen-free environment. MDA-MB-231 (10 × 106) breast cancer cells were subcutaneously implanted into athymic nude mice and CWR22Rv1 (1 × 106) cells into male SCID mice. Mice bearing established tumors (∼100 mm3) were randomized into treatment groups of 6 and dosed with vehicle (40% β-cyclodexdrin in ddH2O) or compounds 20 and 22 (ip, formulated in 40% β-cyclodexdrin in ddH2O, once daily, 5 days a week for 28 days).

In Vivo Antitumor Activity.

We used the National Cancer Institute (NCI) criteria24 to determine tumor growth efficacy of our compounds. Thus, percent test or treatment/control (%T/C), defined as the ratio of the median tumor volume for the treated group vs control group was calculated as %T/C = [(median tumor volume of treated group at day 28)/(median tumor volume of control group at day 28)] × 100. By this criterion, agents that confer %T/C < 42% are considered minimally effective/active, and %T/C < 10% is considered to be highly active.24

Statistical Analysis.

All experiments were carried out in at least triplicate, and results are expressed as the mean ± SE where applicable. Treatments were compared to controls using the Student’s t test with either GraphPad Prism or Sigma Plot. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from NIH and NCI (Grant 1RO1CA129379) and from start-up funds from University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Center for Biomolecular Therapeutics (CBT), Baltimore, U.S., to V.C.O.N.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- AR

androgen receptor

- AR-V7

type of slice variant androgen receptor

- ATRA

all-trans-retinoic acid

- BC

breast cancer

- CRPC

castration resistant prostate cancer

- eIF4E

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

- fAR

full-length AR

- GI50

concentration of agent/compound needed to inhibit cell growth by 50%

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- MNKDAs

Mnk degrading agents

- Mnks

MAPK-interacting kinases

- peIF4E

phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

- NR

novel retinamides

- PC

prostate cancer

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- 4-HPR

4-hydroxyphenylretinamide

- 13-CRA

13-cis-retinoic acid

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

HPLC chromatograms and high resolution mass spectral data for compounds 16–20 and 33–40. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Vincent C. O. Njar is the lead inventor of the novel compound disclosed in this manuscript and patents and technologies thereof owned by the University of Maryland, Baltimore. The other authors, including Hannah W. Mbatia, Senthilmurugan Ramalingam, and Vidya P. Ramamurthy, are also co-inventors on a pending patent to protect the novel compounds of this manuscript.

NOTE ADDED AFTER ASAP PUBLICATION

After this paper was published ASAP on February 12, 2015, a correction was made to Figure 5. The corrected version was reposted February 26, 2015.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Avdulov S; Li S; Michalek V; Burrichter D; Peterson M; Perlman DM; Manivel JC; Sonenberg N; Yee D; Bitterman PB; Polunovsky VA Activation of translation complex eIF4F is essential for the genesis and maintenance of the malignant phenotype in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Cell 2004, 5 (6), 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gebauer F; Hentze MW Molecular mechanisms of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol/italic> 2004, 5 (10), 827 –835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sonenberg N; Hinnebusch AG Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 2009, 136 (4), 731–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Nasr Z; Robert F; Porco JA Jr.; Muller WJ; Pelletier J eIF4F suppression in breast cancer affects maintenance and progression. Oncogene 2013, 32 (7), 861 –871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Robichaud N; Del Rincon SV; Huor B; Alain T; Petruccelli LA; Hearnden J; Goncalves C; Grotegut S; Spruck CH; Furic L; Larsson O; Muller WJ; Miller WH; Sonenberg N Phosphorylation of eIF4E promotes EMT and metastasis via translational control of SNAIL and MMP-3. Oncogene 2014, 10.1038/onc.2014.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; (c) Wendel HG; Silva RL; Malina A; Mills JR; Zhu H; Ueda T; Watanabe-Fukunaga R; Fukunaga R; Teruya-Feldstein J; Pelletier J; Lowe SW Dissecting eIF4E action in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2007, 21 (24), 3232–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Aktas BH; Qiao Y; Ozdelen E; Schubert R; Sevinc S; Harbinski F; Grubissich L; Singer S; Halperin JA Small-molecule targeting of translation initiation for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2013, 4 (10), 1606–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bitterman PB; Polunovsky VA Attacking a nexus of the oncogenic circuitry by reversing aberrant eIF4F-mediated translation. Mol. Cancer Ther 2012, 11 (5), 1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bitterman PB; Polunovsky VA Translational control of cell fate: from integration of environmental signals to breaching anticancer defense. Cell Cycle 2012, 11 (6), 1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Carroll M; Borden KL The oncogene eIF4E: using biochemical insights to target cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res 2013, 33 (5), 227–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Diab S; Kumarasiri M; Yu M; Teo T; Proud C; Milne R; Wang S MAP kinase-interacting kinases-emerging targets against cancer. Chem. Biol 2014, 21 (4), 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Graff JR; Konicek BW; Vincent TM; Lynch RL; Monteith D; Weir SN; Schwier P; Capen A; Goode RL; Dowless MS; Chen Y; Zhang H; Sissons S; Cox K; McNulty AM; Parsons SH; Wang T; Sams L; Geeganage S; Douglass LE; Neubauer BL; Dean NM; Blanchard K; Shou J; Stancato LF; Carter JH; Marcusson EG Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation factor eIF4E expression reduces tumor growth without toxicity. J. Clin. Invest 2007, 117 (9), 2638–2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hong DS; Kurzrock R; Oh Y; Wheler J; Naing A; Brail L; Callies S; Andre V; Kadam SK; Nasir A; Holzer TR; Meric-Bernstam F; Fishman M; Simon G A phase 1 dose escalation, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic evaluation of eIF-4E antisense oligonucleotide LY2275796 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 2011, 17 (20), 6582–6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Konicek BW; Stephens JR; McNulty AM; Robichaud N; Peery RB; Dumstorf CA; Dowless MS; Iversen PW; Parsons S; Ellis KE; McCann DJ; Pelletier J; Furic L; Yingling JM; Stancato LF; Sonenberg N; Graff JR Therapeutic inhibition of MAP kinase interacting kinase blocks eukaryotic initiation factor 4E phosphorylation and suppresses outgrowth of experimental lung metastases. Cancer Res 2011, 71 (5), 1849–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Altman JK; Szilard A; Konicek BW; Iversen PW; Kroczynska B; Glaser H; Sassano A; Vakana E; Graff JR; Platanias LC Inhibition of Mnk kinase activity by cercosporamide and suppressive effects on acute myeloid leukemia precursors. Blood 2013, 121 (18), 3675–3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Ramalingam S; Gediya L; Kwegyir-Afful AK; Ramamurthy VP; Purushottamachar P; Mbatia H; Njar VC First MNKs degrading agents block phosphorylation of eIF4E, induce apoptosis, inhibit cell growth, migration and invasion in triple negative and Her2-overexpressing breast cancer cell lines. Oncotarget 2014, 5 (2), 530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramamurthy VP; Ramalingam S; Gediya LK; Kwegyir-Afful AK; Njar VCO Simultaneous targeting of AR and MNK signaling pathways by novel retinamides induce profound antitumor and anti-invasive activities in human prostate cancer cell lines. Oncotargetnline early access]. Published: December 26, 2014.

- (9).Hou J; Lam F; Proud C; Wang S Targeting Mnks for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2012, 3 (2), 118–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bain J; Plater L; Elliott M; Shpiro N; Hastie CJ; McLauchlan H; Klevernic I; Arthur JS; Alessi DR; Cohen P The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. gBiochem. J 2007, 408 (3), 297–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Teo T; Lam F; Yu M; Yang Y; Basnet S; Albrecht H; Sykes M; Wag S Pharmacologic inhibition of Mnks in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Pharmacol, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (12).(a) Njar VC; Gediya L; Purushottamachar P; Chopra P; Vasaitis TS; Khandelwal A; Mehta J; Huynh C; Belosay A; Patel J Retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents (RAMBAs) for treatment of cancer and dermatological diseases. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2006, 14 (13), 4323–4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Patel JB; Huynh CK; Handratta VD; Gediya LK; Brodie AM; Goloubeva OG; Clement OO; Nanne IP; Soprano DR; Njar VC Novel retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents endowed with multiple biological activities are efficient growth inhibitors of human breast and prostate cancer cells in vitro and a human breast tumor xenograft in nude mice. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47 (27), 6716–6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Bissantz C; Kuhn B; Stahl M A medicinal chemist’s guide to molecular interactions. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53 (14), 5061–5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Purushottamachar P; Godbole AM; Gediya LK; Martin MS; Vasaitis TS; Kwegyir-Afful AK; Ramalingam S; Ates-Alagoz Z; Njar VC Systematic structure modifications of multitarget prostate cancer drug candidate galeterone to produce novel androgen receptor down-regulating agents as an approach to treatment of advanced prostate cancer. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56 (12), 4880–4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Clamon G; Chabot GG; Valeriote F; Davilla E; Vogel C; Gorowski E; Birch R Phase I study and pharmacokinetics of weekly high-dose 13-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Res 1985, 45 (4), 1874–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reynolds CP; Matthay KK; Villablanca JG; Maurer BJ Retinoid therapy of high-risk neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett 2003, 197 (1–2), 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Veal GJ; Cole M; Errington J; Pearson AD; Foot AB; Whyman G; Boddy AV; Group UPW Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin) in children with high-risk neuroblastoma a study of the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96 (3), 424–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Marill J; Capron CC; Idres N; Chabot GG Human cytochrome P450s involved in the metabolism of 9-cis- and 13-cis-retinoic acids. Biochem. Pharmacol 2002, 63 (5), 933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]